Concentration of media ownership remains important in the digital ecosystem. However, the definition and measurement methods may change, in the changing media environment. In this blogpost, Roberta Carlini presents and explains the updated method by which we measure media ownership concentration risks in the Media Pluralism Monitor, in the tenth year of its implementation.

The indicator on media ownership concentration in the Media Pluralism Monitor

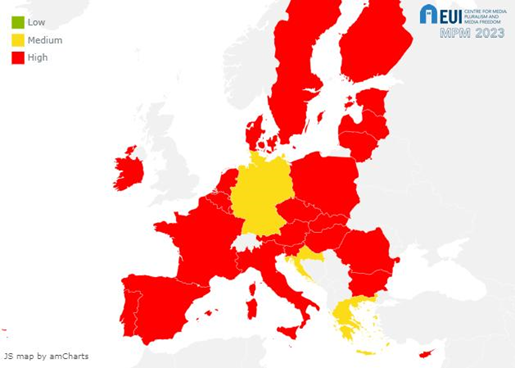

In recent years, a common trend towards increasing concentration of media ownership emerged at worldwide level (Noam et al., 2016). In the EU countries, the results of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) for the indicator assessing the risk of media ownership concentration show an increase of the average risk level from 80 to 86%. It is the highest level of risk among the 20 indicators composing the MPM.

Source: MPM2023

For this indicator, named “Plurality of media providers”, no country is at low risk, and only four countries score medium risk: Greece, Germany, The Republic of North Macedonia and Croatia. This result on one hand highlights the relevance of the issue of media ownership concentration; on the other hand, it provides a flat scenario, with the risk of falling short in analysing differences among the different economies and media systems, and the impact of the digital evolution. To address this issue, a fine-tuning of the MPM methodology in evaluating risk of concentration in the media sector is needed.

Media ownership and media pluralism

The tendency of the media industry toward concentration is not a recent phenomenon, being related to technological and economic features which emphasise the role of economies of scale. What is new, in the digital environment of the media, is the high concentration in the distribution side of the market – due to the dominant role of a few information intermediaries – and the disruption of legacy media’s business model, which is pushing the media industries to merge with their former competitors in order to survive (European Commission 2022, Chapter 2). Furthermore, it highlighted the need to re-conceptualize the definition and the measure of opinion power, in the changing media consumption habits. The idea that abundance and accessibility of information on the internet would reduce the influence of ownership concentration has not been proven and is contested (Baker 2007; Schlosberg 2017). Besides, from a policy perspective, the recent evolution in the EU regulation could lead, for the first time, to a harmonised legal framework to address concentration issues in the media market, with the proposed “media pluralism test” to assess media concentrations in member states media markets and in the EU internal market (Brogi et al. 2023).

How the Media Pluralism Monitor evaluates media ownership concentration

In the MPM design, media ownership concentration is one of the five indicators that contributes to assessing the risks for the Market Plurality area in the media sector. Since the implementation of the MPM2020, the area has been restructured to better monitor digital risks. The Monitor considers media providers and the digital intermediaries (referring to online platforms, such as Google, Facebook or Instagram, whose impact is evaluated in the indicator on Plurality of digital markets) separately. In each case, the risks for market pluralism are evaluated taking into consideration:

- the legal framework, i.e. the existence and effectiveness of media-specific rules to prevent market dominance in the media sector(s); and

- the situation on the ground.

In the case of media concentration, the latter is assessed using numeric indicators of concentration: the Top4 index[1], which measures the share of the four leading groups in each media sector (horizontal concentration: audiovisual, radio, newspapers, online media) and on the whole market (cross-media concentration). The Top4 index is calculated both in terms of market (revenues share) and audience/circulation. Since the first implementation of the MPM, ten years ago, the thresholds of concentration have been the following:

- Top4 below 25%: low risk

- Top4 between 25 and 50%: medium risk

- Top4 above 50%: high risk

The restructuring of the indicator in the MPM2020 led to the inclusion of a specific assessment for the online media providers, and in so doing it allowed to record the shortcomings of the obsolete regulatory framework (which in most of the countries does not include digital media); and a relatively lower degree of ownership concentration in the digital media sphere – even though this result is influenced by a lack of reliable data for revenues in many countries, and by a general obscurity of measurement methods for audience. The second novelty introduced since MPM2020 is the indicator on online platforms concentration (named Plurality in digital markets), which highlights a situation of even higher concentration of the digital intermediaries of information, based on the Top4 players in the digital advertising market and the total digital audience.

The methods of measurement: the choice of the Top4 index

To revise and fine-tune the tool for the assessment of the year 2023 (MPM2024), we addressed two issues: if the Top4 index to measure concentration is fit for the evaluation of the media market and opinion power; and if, in the evolving situation, the thresholds designed in 2014 are still valid. In a workshop held in Florence on 30 June 2023, researchers contributing to the MPM from smaller countries highlighted the fact that the Top4 measurement does not allow to take into consideration all relevant dimensions of the market: it is even possible that, in smaller countries, there are just 2 players, or even only 1, in a sector with high fixed costs of that of audiovisual media.

As underlined in the MPM foundational study (Valcke et al. 2009), these methods of measurement are used in competition enforcement to indicate the degree to which firms can control supply or price in a market, “but efforts have been made to use these as evidence of media concentration and diminished pluralism”. The study highlights that the Top4 analysis can provide quick measures of market control, and reports that “when the top-four firms control more than 50 percent of a market, or the top-eight enterprises account for more than 70 percent of a market, undesirable concentration or control is said to be evident” (p. 73). The study also highlights the limits of the measurement and evaluates the possible alternatives, such as the HHI, the Diversity index, and the Noam index.[2] The worldwide mapping of media ownership provided by Noam (2016) uses and compares the outcomes of different indexes, including the number of voices; C4 and C1[3]; HHI; Noam Index; and Power Index.

While the Diversity index has been extensively criticised in literature for its inadequacy, the other metrics have a practical obstacle for the sake of the MPM exercise. In fact, the MPM uses secondary data to assess the risks, and most of the countries lack the data that are necessary to calculate the HHI, NI, and PI. Therefore, we conclude that despite its limitations, the Top4 index remains a valid indicator of media ownership concentration; and, given the peculiarity of the media sector, it should be calculated – as in the MPM questionnaire – both based on revenues and audience share: a media outlet can be dominant in the market (e.g., in the case of pay-tv) even with a relatively small audience. In confirming the method of measurement based on the Top4 index, some caveats must be added:

1) in the digital environment, audience measurement methods are fragmented and often not transparent. In this regard, the role of the MPM exercise is also to point out the blind spots and ask for transparent and standarised data for researchers and regulators.

2) Another drawback of the Top4 index is that it does not account for the distribution of shares between the Top4 companies: a situation in which the Top4 have relatively equal shares, is different from a case in which the Top1 has the majority shares, while the other three are much less significant. The narrative reports from each country may help to address this issue, better explaining the situation on the ground.

The thresholds to assess concentration:

When it comes to the thresholds to assess the risks of concentration, the literature and the evolution of competition enforcement leave room to different choices. According to Noam (2016), if the sum of the Top4 players is below 40% of the market, the industry tends to be competitive, whereas above 40% the industry can be considered an oligopoly. The US Census Bureau, for example, uses Top4 for a number of industries, and considers market concentration to be high when the index is above 40%. In the EU, the study on implementation of the new provisions in the revised AVMS directive (European Commission 2020), in evaluating the effectiveness of the anti-concentration rules on media ownership, proposes the following thresholds:

- Top4 below 40%: low concentration

- Top4 between 40-70%: medium concentration

- Top4 above 70%: high concentration

Based on an empirical comparison between Top4 and HHI, Naldi and Flamini (2014) propose a slightly different classification, placing the threshold of “tight oligopoly” above 60% (see table 3, p. 5). However, it is worth noting that their analysis is not focused on the media sector.

Considering the tendency emerging from competition cases, there may be a rationale to update the original thresholds based on which the risk of concentration is assessed in each sector. Even though there is no agreed definition, we can build on the above-mentioned literature to indicate new thresholds, taking into consideration the peculiarity of the media sector and the MPM standards.

For the threshold of low risk, the most widely accepted definitions envisage a competitive market below 40%. The threshold of high risk will be raised from 50 to 60%: this is because 1) the 70% threshold indicated by the study on AVMS refers to a sector that is the most concentrated (also) for structural reasons, and would be too high for the other media sectors; 2) the threshold of 60% would also be in line with a more nuanced graduation of risks that in the future can be developed, shifting from the current three-risk level (low, medium, high) to a 5-risk level (very low, low, medium, high, very high: in this case, the MPM thresholds of risk would become, respectively, 20, 40, 60 and 80%).

To conclude, we will assess a media sector as competitive with a Top4 index below 40%, and as highly concentrated with a Top4 index above 60%. With this revision, the MPM threshold would change slightly, in the direction of being a bit less “severe”, in so doing acknowledging the need to take into consideration the digital ecosystem of the media in evaluating the concentration per sector.

- Top4 below 40% = low risk

- Top4 40-60% = medium risk

- Top4 above 60% = high risk

The new thresholds are considered in assessing the risks for horizontal concentration. On the contrary, the thresholds to evaluate cross-media concentration (the share of the top leading groups on the whole media market) would not change.

As a consequence of this revision, the results of MPM2024 for concentration should be compared with the results of the previous years cautiously, as the differences may depend upon the impact of the methodological changes.

Conclusions

While we consider an index weighted on the dimension of the markets as the most accurate way to assess market concentration, the data currently available and thus the methodology of the MPM (which builds on the use of secondary data) makes the Top4 index the preferable measurement, which has also the advantage of being of “intuitive simplicity” (Noam 2016). We also emphasise that the results must be understood and interpreted in the national context, whose description is provided in the MPM country reports – which should also provide information about the distribution of shares among the Top4. Finally, the thresholds based on which the risk of concentration is assessed need a slight revision. We recommend an increase of the thresholds of concentration – based on literature and cases, but also on a normative approach that considers media market plurality not only from the economic perspective (i.e. impact on consumers and prices) but from a holistic perspective. Such an approach is interested in an open, competitive, and fair media market, in which many diverse players can co/exist, and (what’s more important) which allows new players to enter. This is essential to media pluralism and diversity, and thus to the well-functioning of democracy.

[1] Top4 (or CR4, or C4) is a concentration measure that presents the combined market share of top four companies in an industry.

[2] The HHIl index is a measure of the size of firms in relation to the industry and it is calculated by squaring the market share of each competing firm in the industry and then summing the resulting numbers.It is more informative than Top4, and it has a wide practical use by competition authorities – but it requires to know the market shares of all the firms in the market (or at least the first 50) to be calculated. The Diversity index is a tool created in 2003 in the US by the Federal Communications Commission, modelled on HHI, and modified with the goal to measure diversity rather than market power, thus including the audience use in local markets. It was rejected by Courts and widely criticised in literature (Valke et al., p. 74). The Noam Index “is a diversity index that uses the net n voice measures for industries and countries to account for media pluralism (…). It is calculated by taking an industry HHI and dividing it by the square root of the number of voices present in that industry” (Noam et al. 2016, p. 1029).

[3] C1 (or Top1) measures the market share of the top firm in each industry.

Other references:

Baker, C. E. (2007). Media Concentration and Democracy. Why Ownership Matters. Cambridge University Press.

Brogi, E. et al. (2023). The European Media Freedom Act : media freedom, freedom of expression and pluralism, EUI, RSC, Research Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom,, PE 747.930 – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/75938

European Commission (2020) Study on the implementation of the new provisions in the revised Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) Final report.

European Commission European Commission, Di-rectorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, Parcu, P., Brogi, E., Verza, S. (eds). Study on media plurality and diversity online – Final report, Publications Office of the European Union.

Naldi, M., & Flamini, M., (June 11, 2014).The CR4 Index and the Interval Estimation of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index: An Empirical Comparison Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2448656 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2448656

Noam, E. M., & Concentration Collaboration, T. I. M. (2016). Who Owns the World Media? Media Concentration and Ownership around the World. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199987238.001.0001

Schlosberg, J. (2017). Media ownership and agenda control: the hidden limits of the information age. Routledge

Valcke, Peggy et al. (2009). Independent Study on Indicators for Media Pluralism in the Member States – Towards a Risk-Based Approach. Available at: https://ec-europa-eu.eui.idm.oclc.org/information_society/media_taskforce/doc/pluralism/pfr_report.pdf