By Maria Žuffová

On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, our Research Associate Mária Žuffová summarises the evidence from the Media Pluralism Monitor 2023 on the attacks and threats against women journalists. She argues that governments must adopt measures to increase the protection of journalists, especially women.

On 16 October 2017, Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who led the Panama Papers investigation into corruption in Malta, was killed by a bomb placed in her car near her home in Bidnija. Europe, long seen as a safe place to do independent public-interest journalism, was shocked by her murder. Journalists’ killings, except for terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo, were extremely rare. In the preceding twenty years, no woman journalist was murdered for the conduct of her work in any EU member state. Caruana Galizia’s murder has had profound consequences on the well-being of her colleagues, who recognised the increased risks they faced in the pursuit of their watchdog role. Simultaneously, her murder mobilised civil society to organise large protests demanding an end to impunity and the journalistic community to speak out about their everyday experiences of violence and threats.

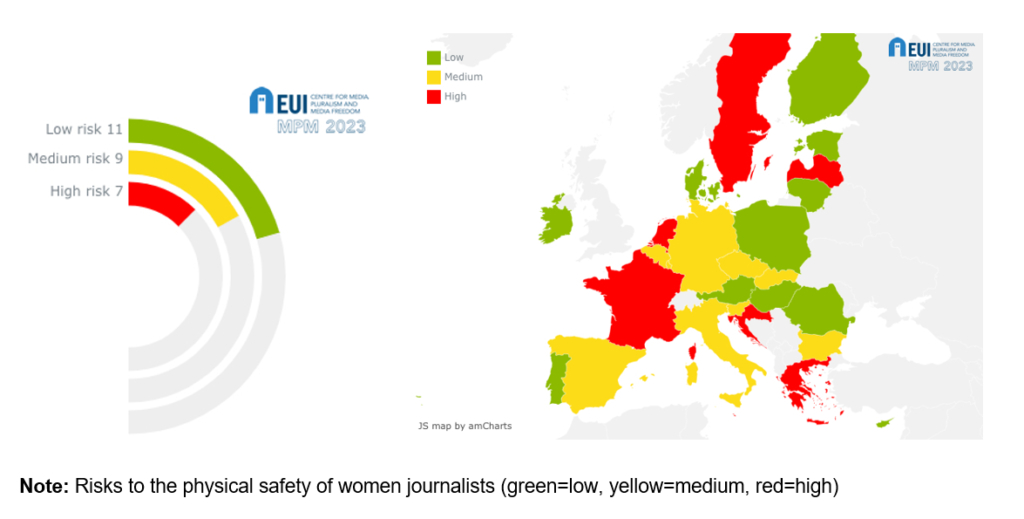

The Media Pluralism Monitor’s (MPM) findings show that gender-based violence against women journalists represents a significant problem across Europe. Although the risk to women journalists’ physical safety has decreased in 2022 compared to past iterations of the MPM, it was evaluated as low in only 11 of the 27 EU countries. The risk was assessed as medium in nine and high in seven remaining EU countries. As the CMPF pointed out two years ago, the lack of empirical data remains the main challenge. Most national governments fail to understand the extent of the issue as they do not collect data on violence targeting media professionals. Moreover, journalists tend not to report attacks and threats because they deny risk to them or do not have trust in their national criminal justice system, among many other reasons. In the absence of data, it is very difficult to propose effective measures to tackle it.

Nonetheless, the emerging data suggests the situation is concerning. For instance, in 2022, 87 attacks against journalists occurred only in Germany. No complete gender-disaggregated data on incidents are available. In France, several scandals broke, revealing pervasive harassment of women journalists in newsrooms. Testimonies included severe sexual offences. Last year, physical attacks against women journalists were also reported in Greece and Spain during protests and demonstrations. In Greece, even though journalists were identifiable as the press, they were attacked by police forces who should protect them.

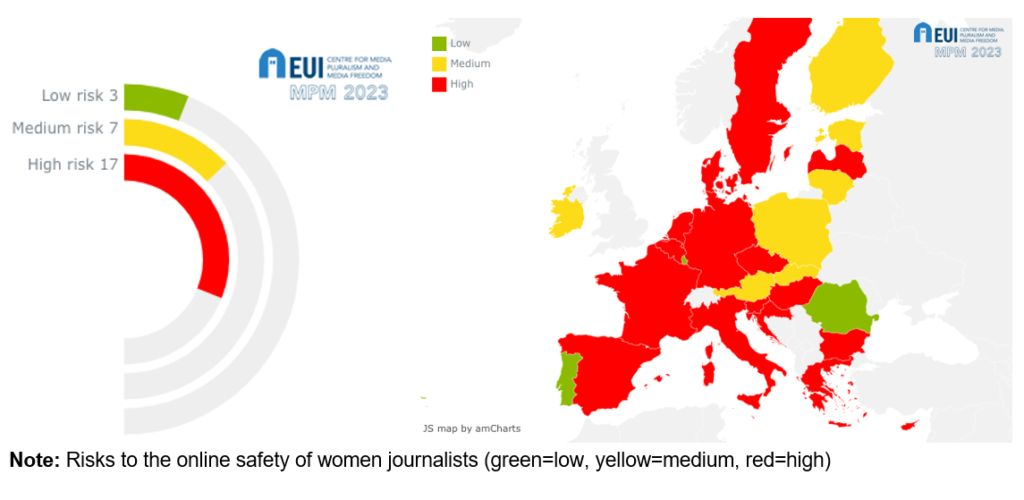

While the number of physical attacks against women journalists decreased compared to the previous years, the threats and harassment in the online environment have been on the rise.

According to the MPM findings, the risk to women journalists’ safety in the online environment was evaluated as high in 17 of the 27 EU countries. It was assessed as medium in seven and low in only three EU countries – Luxembourg, Portugal, and Romania. However, even these countries may not be immune to online threats and harassment, as they often go unreported and, thus, underestimated, as mentioned above. For instance, in Italy, in the first nine months of 2022, 24 incidents of intimidating journalists in the online environment were reported to the police. However, the statistics collected by the civil society sector suggest that the number of journalists attacked is much higher. Similarly, research conducted in the Netherlands showed that most journalists do not contact PersVeilig (a platform to report incidents) when they become a victim of threats or violence.

The lack of official data is partly compensated by research surveys. Those indicate that women journalists experience far more online hate speech and harassment than their male colleagues and that its extent is pervasive. For example, the Persveilig survey showed that eight out of ten Dutch women journalists were a victim of some form of aggression, intimidation, or violence in the past year. Almost a third of them experienced it every month. An older survey conducted by the Swedish Media Publishers’ Association concluded that 36% of female journalists were exposed to threats or harassment in or because of their work in a studied year.

In some cases, the online attacks were fuelled by political actors who should instead help to create and protect safe and favourable conditions for independent journalism. For example, in Slovakia, radio presenter Marta Jančkárová was targeted by the Smer-SD Party for not allowing an uninvited party colleague to participate in her discussion programme. Jančkárová received phone calls and emails from Party’s supporters threatening her with death, torture, rape, and physical harm to her family members. This was not just one isolated example. The political elite’s hostility toward media is increasing across Europe. Similar incidents were reported in 2022 in Hungary, Latvia, and Spain.

By providing citizens with timely and reliable information, the media helps us expand our understanding of complex socio-political issues and navigate changes. Threats and attacks against women journalists do not impact only them but also us – their audiences. If they get discouraged from covering politics or other polarising topics and decide to leave the profession, the plurality of information we receive will diminish. Caruana Galizia’s murder underscored the urgent need for enhanced protection of journalists, especially women. Now, it is time for the national governments to adopt concrete measures.

Literature:

Bleyer-Simon, Konrad et al. (2023). Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. CMPF, EUI.

Carlini, R., Trevisan, M., & Brogi, E. (2023). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Italy. CMPF, EUI.

Clark, M. and Horsley, W. (2020). A mission to inform: Journalists at risk speak out. Council of Europe.

De Swert, K., Schuck, A., Boukes, M., Dekker, N., & Helwegen, B. (2023). Monitoring

media pluralism in the digital era: application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: the Netherlands. CMPF, EUI.

Ouakrat, A. & Larochelle, L. (2023). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the

Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: France. CMPF, EUI.

Papadopoulou, L., & Angelou, I. (2023). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Greece. CMPF, EUI.

Suau, J., Capilla Garcia, P., Puertas Graell, D., Valsells, R., Franquet, M., Yeste Piquer, E., Cordero Triay, L., & Sintes-Olivella, M., (2023). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Spain. CMPF, EUI.