Pluralism of the media constitutes one of the essential pillars of democracy. Freedom of expression and freedom and pluralism of the media are enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Article 11), and their protection is underpinned by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. This report presents the results and the methodology of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM2021). This is a tool that is geared to assess the risks to media pluralism in EU member states and in candidate countries (32 countries in total). The Media Pluralism Monitor has been implemented, on a regular basis, by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, since 2013/2014 (last implementation MPM2020), and it is based on a holistic perspective, taking into account legal, political and economic variables that are relevant to analysing the levels of plurality of media systems in a democratic society. This implementation covers the year 2020. As mentioned above, this edition of the MPM covers 32 countries. It is relevant to acknowledge, as it is also important to interpret the results of this round of the implementation of the tool, that the analysis this year does not cover the United Kingdom (MPM2020 included the UK too) and covers 5 candidate countries (MPM2020 covered 2 candidate countries).

Fundamental Protection

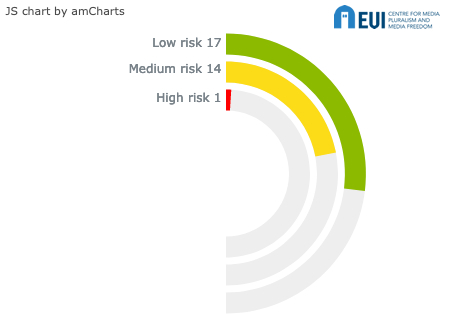

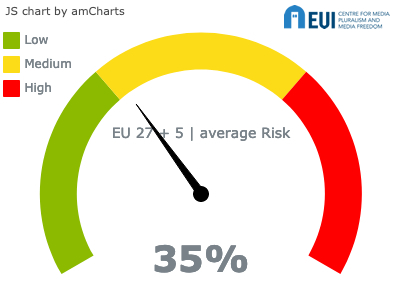

The Fundamental Protection area of the MPM considers the necessary preconditions for media pluralism and freedom, namely, the existence of effective regulatory safeguards to protect the freedom of expression and the right to seek, receive and impart information; favourable conditions for the free and independent conduct of journalistic work; independent and effective media authorities; and the universal reach of both traditional media and access to the Internet. Similarly, as in the previous round of the MPM, the Fundamental Protection area also focuses on the challenges posed by the online environment to the plurality of the media landscape. It therefore assesses the protection of freedom of expression online, data protection online, the safety of journalists online, levels of Internet connectivity, and the implementation of European net neutrality obligations. In the MPM2021, the narrow majority of the countries analysed scored a low risk in relation to the Fundamental Protection area: 17 of the 32 countries assessed scored as a low risk (namely, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Republic of North Macedonia, Slovakia, and Sweden). Fourteen countries scored as a medium risk (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain), and one country scored as a high risk (Turkey, as was the case in the previous MPM round).

The assessment on Fundamental Protection shows a deteriorating situation in comparison with MPM2020 in three of the five indicators, in particular, the indicators on Protection of freedom of expression, Protection of the right to information and Journalistic profession, standards and protection. This negative shift can be explained by the governments’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the MPM2021 country reports (Bátorfy & Szabó, 2021; Milutinovic, 2021; Popescu et al., 2021; Spassov et al., 2021) have concluded that governments adopted legal and regulatory measures to prevent spreading false or distorted pandemic-related information in the traditional and/or digital media, which, however, may have long-term implications for freedom of expression and the right of access to information, and, ultimately, to the ability of journalists to fulfil their monitorial role. As Radu (2020) has argued, once these measures are adopted, revoking them may become challenging, and they may stay in place for much longer than had initially been intended, renegotiating the balance between freedom of expression and censorship or access to information and government secrecy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also substantially affected the working conditions of journalists (including their physical safety and social security), which has been translated into an increase in risk of seven percentage points, in the indicator on the Journalistic profession, standards and protection, if compared to the previous round of the MPM. The majority of the assessed countries (19 of 32) scored as a medium risk. While 2020 was a year in which no journalist was murdered in the EU member and candidate countries, the numbers of threats to their physical and online safety have been on the rise. Several MPM2021 country reports have mentioned the occurrence of physical attacks on journalists. These were related either to investigative reporting on corruption in the respective countries (Spassov et al., 2021), or happened while journalists were covering mass protests (Klimkiewicz, 2021; Spassov et al., 2021). The violence during protests not only came from the protesters but, in some cases, it was accompanied by violence from the police forces (Rebillard & Sklower, 2021). In line with the available academic and policy research on the safety of journalists (Trionfi & Luque, 2019), the attacks on journalists who cover polarising issues, e.g., those that are related to ethnic or religious issues (Bilić et al., 2021; Popescu et al., 2021), were at a greater risk of threats. The attacks on journalists that arise from political actors have become common in many EU and candidate countries. Given that one of their roles, as policymakers, is to contribute to creating favourable conditions for the free and independent conduct of journalistic work, and they should thus lead in recognising and acknowledging the role of the free press for democratic societies, this trend is very disturbing. The attacks from political actors include anti-press (often vulgar and threatening) rhetoric, but also lawsuits, in particular, strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), which are set out with little or no chance of success, and which usually ask for a disproportionate amount of damages. Threats to journalists have come from the online environment too. Online harassment and threats, especially against women journalists; legal provisions allowing national security services to collect internet and telephone data from citizens in bulk, as a result of the purposes of investigation and surveillance, have been reported in some countries’ reports.

While the risk has increased for the above three indicators, it has dropped for the remaining indicators in this area, in particular, for the indicator on the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority (from 24% to 23%) and the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet (from 39% to 33%), which both scored as a low risk, on average.

As in previous rounds of the MPM implementation, Turkey is the only country that scores as a high risk in Fundamental Protection, confirming a trend to deterioration in the protection of fundamental rights and values. Of particular concern is the still high number of imprisoned journalists in the country, coupled with a lack of independence among the judiciary, and abusive use of the criminal justice system, in particular, when it comes to limiting freedom of expression. The trend to the prosecution of writers, journalists and social media users for insulting President Erdogan has grown. Journalists have extensively been prosecuted and imprisoned on charges of terrorism, insulting public officials, and/or committing crimes against the State.

Market Plurality

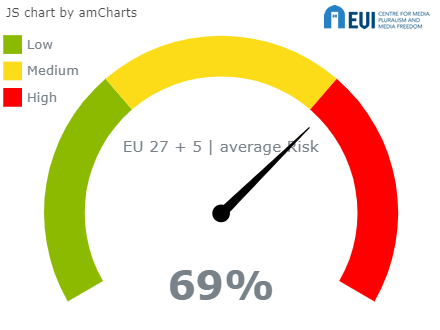

Under the Market Plurality area, the MPM assesses the economic risks to media pluralism, related to the context in which the market players operate. This context is evaluated by considering the legal framework and the situation on the ground; the market indicators evaluate the role of content providers and of digital intermediaries. The threats to market plurality may derive from a lack of transparency and a high concentration of ownership; from the economic conditions of the news media industry; from the pressure of commercial interests on journalistic activity. Traditionally, this area shows, on average, the highest level of risk in the MPM exercise, and it has done so since its first implementation in 2014, mainly because of the high concentration in the news media industry. In more recent years, the deteriorating economic conditions of the news media industry have contributed to rising risk. The MPM2021 assessment for this area is characterised by the COVID-19 shock, which accelerated the declining trend in news media revenues and the shifting of resources towards digital intermediaries. At the same time that this tendency to concentration has continued all of these phenomena have worsened the threats to the economic independence of editorial content from commercial and/or owner influence.

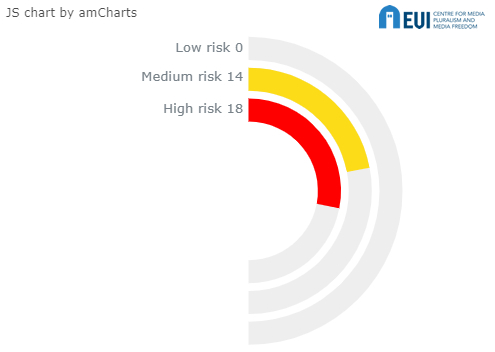

In the MPM2021, the Market Plurality area shows a high risk. The average level of risk is 69% (both for EU and EU + 5). In this area, no country scores as a low risk, 14 countries are at medium risk and 18 countries are at high risk. Although the economic threats to media pluralism have always been a source of concern in the MPM assessment, the high-risk level for the average of the countries in which MPM is implemented had never been touched in the previous rounds (the average level of the risk in this area scored 53% in MPM 2017 and 64% in MPM2020). The main driver of the risks’ growth is the indicator on Media viability, which shifted from medium to high risk in an average of the 32 countries, with no country scoring as a low risk. There were 11 countries that were at medium risk, and 21 countries at high risk. The MPM2021 assessment raises alarm on the economic conditions of professional journalism, with the freelancers and independent journalists suffering most. Although generalized, the economic crisis has impacted differently on the different countries and media sectors; and signals of resilience may be traced in those countries in which alternative business models, ones that do not rely exclusively on advertising, are developed; and in some niches in the digital media outlets, which have managed to resist the market downturn and to benefit from the shift towards digital consumption that has been accelerated by the pandemic. Extraordinary public subsidies helped, in some cases, to counterbalance market losses. Together with the impact of the extraordinary events of 2020, the current MPM assessment highlights the perduring challenges to the media market’s plurality and diversity, deriving from the dominant role of digital intermediaries in both the news consumption and the advertising market.

Political Independence

Political pluralism, as a potential for actively representing the diversity of the political spectrum and of ideological views in the media and other relevant platforms, is one of the crucial conditions for democracy and democratic citizenship. The Political Independence area is assessed by using indicators that evaluate the extent of the politicisation of the distribution of resources to the media; political control over media organisations and content; and, especially, of the public service media. The area evaluates the editorial autonomy to self-regulate in both the traditional and digital news environments, and safeguards against manipulative practices in political advertising in the audiovisual media and on online platforms (including the social media). Media policies and media regulation have mainly been focused on audiovisual media, due to their perceived impact on public opinion, and as a result of their use of finite spectrum resources. As more people are shifting their attention and news habits to online platforms and sources, more attention needs to be given to the conditions in which the political information there is shared, moderated and accessed. Last year’s MPM therefore introduced a set of variables that aim to assess the political control over digital native media, the fairness and transparency of (micro-targeted) political advertising on social media, and on other online platforms, as well as the potential for journalists to self-regulate their activities on social media. In the MPM2021, we further differentiated between political advertisements on digital native news media and on online platforms. The latter play an increasingly important role in political actors’ strategies to reach and persuade voters, which justifies giving this area additional weight in our assessment.

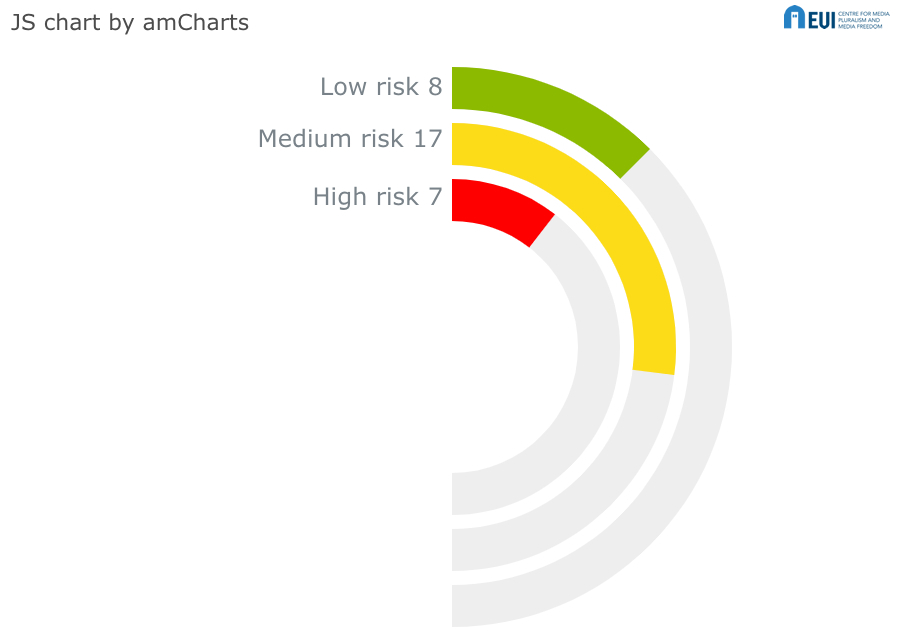

Overall, the Political Independence area is at high risk in 7 countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Turkey). These are exactly the same countries that scored as being at high risk last year. Eight countries are found to be at low risk (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden). Estonia is a newcomer in the group of low- risk countries. 17 countries, including four EU candidates (Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia and Serbia), score as being at medium risk.

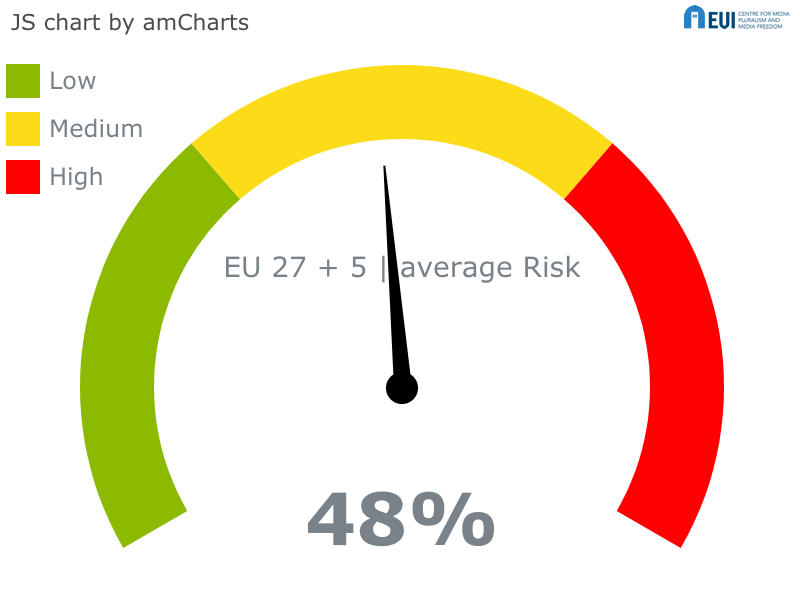

On average, for all of the countries covered by the research, the area risk remained almost the same as in the MPM2020 (when it was 47%), and neither have there been significant changes in the indicators’ risk scores from the MPM2020 to the MPM2021. Turkey continues to be the only country that scores high risks across all five indicators in the area of Political Independence. It is also the only country that scored as being at high risk on the indicator Audio visual media, online platforms and elections. This is the indicator with the lowest risk score in this area, which can be attributed to the fact that political advertising in audiovisual media, especially in the public service media, is strongly regulated across Europe. Bulgaria, Hungary, and Slovenia scored as high-risk in the remaining 4 indicators (Political independence of media; Editorial autonomy; State regulation of resources and support to the media sector; and Independence of public service media governance and funding). While the Audio-visual media, online platforms and elections indicator shows the lowest risk overall (35%, which is at the lower end of medium risk), its digital sub-indicator: Rules on political advertising online, draws a much more gloomy picture (66%, right on the border with high risk). This sub-indicator evaluates the conditions and safeguards for fair play and the transparency of political advertising online, including those online platforms that distribute content. Instruments, like those that ensure transparency in political advertising during election campaigns in the audiovisual media, are not common in the online sphere, where different possibilities are offered, and different techniques are used to influence political opinions. Overall, for all of the 32 countries examined, most of the risks in the area of Political Independence relate to the lack of regulatory, or self-regulatory, protections for editorial autonomy. The risks are further associated with the general lack of political independence of the media, and conflicts of interest between holding government office and media ownership (especially at the local level) are often not effectively regulated. Public service media, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, are at the risk of government interference through the appointment of politically dependent management.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ensuing economic difficulties, we saw an increasing demand for state support in media markets. However, this kind of support can be detrimental, depending on the relevant dynamics. If the criteria for the distribution of direct and indirect subsidies are unclear, or the practice is not transparent, there is risk of state support becoming an instrument for political capture. The findings show that the pandemic did not, in fact, increase the risks associated with direct and indirect support. However, in the case of state advertising – any advertising paid for by governments (national, regional, local) and state-owned institutions and companies to the media – the MPM recorded a slight deterioration of 2 percentage points. State advertising is often used as a means to covertly subsidise news outlets. Due to the pandemic, many governments ran information campaigns to provide information to their citizens on how to stay safe under the current circumstances. 25 countries score a high risk in the variable on state advertising, because they lack the legislation to ensure fair and transparent rules on the distribution of state advertising to media outlets, and, in practice, there is a lack of transparency in regard to the beneficiaries and the amounts spent.

Social Inclusiveness

The Social Inclusiveness area considers access to the media by various social and cultural groups, such as minorities, local/regional communities, people with disabilities, and women. Media literacy, as a precondition for using the media effectively, is also part of the Social Inclusiveness area. In this 2021 version of the MPM, the fights against disinformation and hate speech have been added in the area, as specific digital issues that may hamper social inclusiveness.

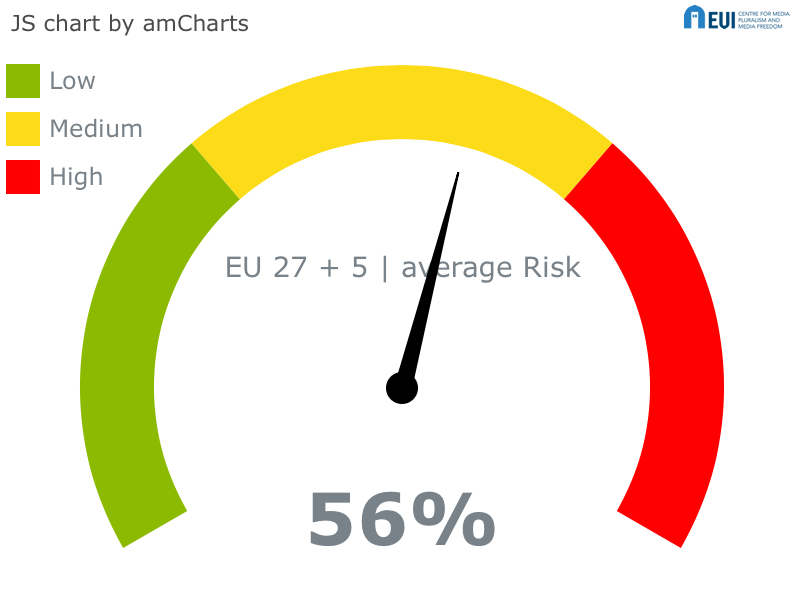

On average, the Social Inclusiveness area scores 56% (i.e., medium) risk. This is 4 percentage points higher than in the MPM2020 (52%). However, it is still in a medium risk band. The difference may be explained by two main factors: 1. the difference in the countries studied, with the removal of the United Kingdom and the addition of three candidate countries, and 2. the addition of a new indicator on Protection against illegal and harmful speech, whose overall score is in the medium risk band.

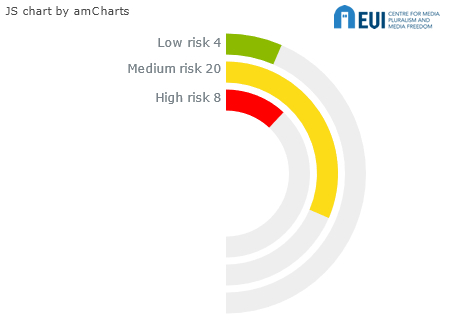

Almost two thirds of the countries (20) score a medium risk (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of North Macedonia, Spain, Slovakia), 8 countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia and Turkey) score a high risk, while only 4 countries (Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden) are in the low risk band for Social Inclusiveness.

Access to media for women is the highest scoring indicator in this area. Women continue to be heavily underrepresented in both media management and reporting. Male experts are more often invited to comment on political programmes, and in articles, than female experts are, and no country scored a low risk on this matter, except for Estonia.

The new indicator on Protection against illegal and harmful speech is the second highest scoring indicator. In most countries, there is no policy framework to fight the spread of disinformation, or else it raises criticism in terms of the respect of fundamental freedoms. Some initiatives have been launched by civil society organizations, but they are often insufficient to face up to the flow of disinformation in the current context. Only two countries have developed a framework that has been assessed as being efficient by the MPM national teams: Germany and Finland. While Germany has opted for a legal framework, Finland has preferred a self-regulatory one. Both options seem to have had a positive impact. However, the relative newness of those frameworks, as well as the difficulty in measuring their achievements through empirical data, make it difficult to evaluate their impact. In Spain and Bulgaria attempts to develop a legal framework with which to fight disinformation has raised serious concerns regarding their impact on Freedom of Expression. Regarding hate speech: in most of the countries studied, the existing framework is not efficient in fighting against hate speech online. The absence of data in many countries has contributed to raising the level of risk, as it points out that the issue may not be taken as seriously as it should be by many of the governments.

Access to media for minorities scores slightly lower in 2021. The difference is due to the inclusion of the sub-indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities within this indicator. The overall score of the sub-indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities is in the medium-risk band, at the fringe of the low-risk band. On the contrary, the risk is higher in regard to the access of minorities to public service media and private broadcasters. The access to airtime is rarely proportionate to the size of the minority, be it a legally recognized minority, or not.

Regarding media literacy: 13 countries score a medium risk (Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain), 11 a high risk (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Malta, Poland, The Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Turkey), and eight countries register a low risk (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden). In the countries presenting a medium or a high risk, media literacy activities tend to be organized by civil society organisations outside the compulsory curriculum. In general, they are targeting urban and young populations. Germany, Finland and the Netherlands have the best comprehensive media literacy policies among the countries studied.

The medium overall risk presented by the indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media is comparable to that in 2020. The main risk in this area is linked to the access to Community media. The absence of adequate regulatory framework relating to community media is an issue in 8 countries: Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Serbia, and Spain. In fifteen countries, their independence is not safeguarded, namely, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Serbian, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Turkey. With regard to local and regional media, the main issue is the result of the lack of sufficient subsidies, which is applicable to 25 countries (Albania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Poland, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, Sweden, and Turkey).

MPM2021 devotes a special focus to the evaluation of the specific risks to media pluralism in the digital environment.

Media pluralism in a digital environment

Since the 2020 implementation, the MPM has put special focus on the evaluation of the specific risks to media pluralism in the digital environment. In the MPM2021, the risk scores of the digital component increased, if compared to the previous implementation of the Monitor, in all the areas. With the exception of the Market Plurality area, the risk scores of the digital component of each area are, in general and on average, higher than the overall score in that area.

In the Fundamental Protection area, the average score of the digital variables results in the same range of the overall score, medium risk, but at a slightly higher level. While the assessment on the digital dimension of Fundamental Protection is somehow comparable to the overall score for this domain, it presents some specific elements that generate additional risks. The higher scores are explained by higher risks in the “digital score” of the indicators on Journalistic profession, standards and protection, and the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet. The results of MPM2021 highlight the risks that are related to the digital safety of journalists, which are higher than the threats to their physical safety.

In the Market Plurality area, the average score of the digital variables is lower than the overall risk for the same area. Although the difference is slight (three percentage points), it brings the assessment for the digital variables into the range of medium risk, whereas the overall assessment is in the high risk range. The digital risk is higher for the indicators of Transparency of media ownership and Online platforms concentration and competition enforcement, whereas it is lower in the other indicators from the same area. Two reasons may help to explain the lower risk in this area for the digital variables: the historically high degree of ownership concentration, and the threats to the economic sustainability of the traditional media, both factors that are not mitigated but that are worsened, by the digital competition. On the other hand, growing risks in the digital environment are related to the need to update the regulatory framework in relation to the ownership’s transparency; and the highest level of risk is confirmed when it comes to the online platforms, which dominate the advertising market, whose concentration is not effectively addressed by the traditional competition tools.

In the Political Independence area, the average score of the digital variables is five percentage points higher than the overall score, but is still in the same medium risk range. In this area, the higher risks are mainly related to variables relating to political advertising online, which are measured in the indicator on Audio visual media, online platforms and elections. The vast majority of countries (23 of 32) have no, or have insufficient, rules with which to ensure the transparency and fairness of online election campaigns. In 15 countries, including four candidate countries, the rules for political parties, and candidates competing in elections, in relation to reporting on campaign spending on online platforms in a transparent manner, are completely lacking. The digital dimension recorded additional risks in relation to the lack of self-regulation in journalists’ social media use, and to a lack of effective regulation that adequately covers the online public service missions of the PSM, while considering its potential implications for commercial media actors. Meanwhile, a positive note comes from the political independence of the digital native news media sector, although concerns emerge in several countries in relation to a lack of transparency in the ownership data of digital natives.

In the Social Inclusiveness area, the average score of the digital variables is slightly higher than the overall score. In this area, the digital risks are associated with low digital skills, which, as a consequence, causes the higher vulnerability of individuals. Another source of digital risk in this area is measured by the indicator on Protection against illegal and harmful speech, which assesses the extent and the effectiveness of policies and initiatives to counteract illegal and harmful speech online.