Download the report in .pdf

English – Swedish

Author: Mathias A. Färdigh (University of Gothenburg)

December, 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Sweden, the CMPF partnered with Dr. Mathias A. Färdigh (University of Gothenburg), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

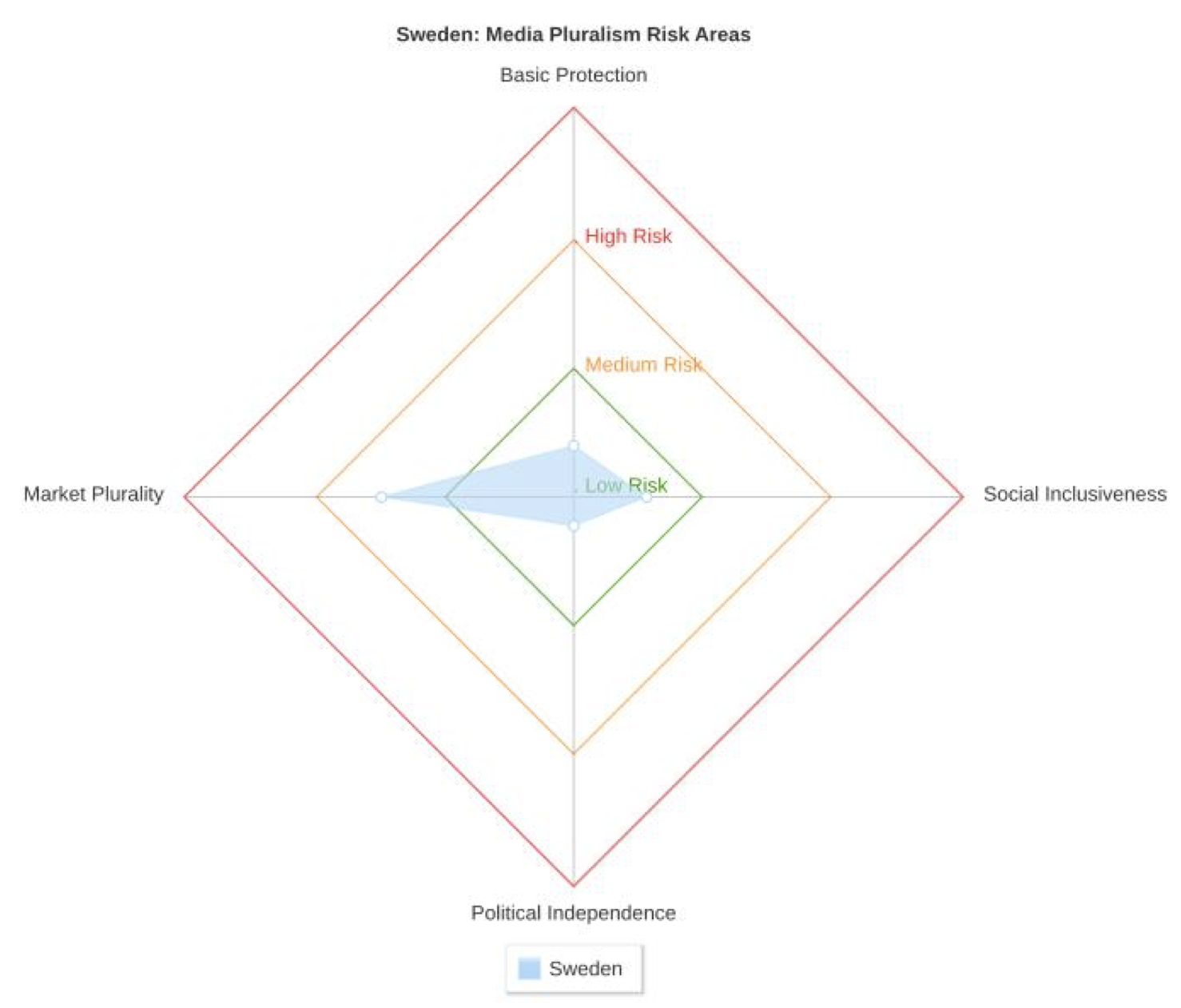

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk.[1]

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Sweden is the third-largest country in Western Europe after France and Spain. In relation to its area, Sweden is a sparsely populated country with about 9.9 million inhabitants of which about 2 million are under the age of 18 years and 15% were born in a foreign country. Swedish is the official language and the vast majority of Swedes also speak English. Sweden has five official national minority languages and countless other languages are spoken by the diverse population. After Swedish, the most common are Finnish, Serbo-Croatian, Arabic, Kurdish, Spanish, German and Farsi.

Sweden is a parliamentary democracy. There is a clear left–right dimension in the political preferences of the Swedish electorate and the political parties are generally grouped into two blocs. A left-of-centre bloc consists of the Social Democrats, the Left Party and the Green Party, and the centre–right bloc consists of the Moderate Party, the Centre Party, the Liberal Party and the Christian Democrats. Isolated from these two blocs are the right-wing national conservative Swedish Democrats, which is Sweden’s third-largest party. Sweden is currently governed by a minority coalition between the Social Democrats and the Green Party.

Over the two last decades, the media in Sweden have undergone major changes and shifts in terms of regulation and actors. The Swedish media landscape is dominated by public service media (SVT, SR, UR). The Swedish public service television company (SVT) has the widest range of programming of all TV companies in Sweden while the Bonnier family, the Stenbeck family and Schibsted are the largest private actors. All forms of media are open to private competition. There is at the same time no information about revenues of the big international actors such as Google, Facebook, Netflix, Apple and others, on the Swedish market. There is a general need for more and better data.

Sweden has a strong tradition in print media and this is characterised by a high newspaper penetration. The level of newspaper circulation is among the highest in the world. There is at the same time a shift in revenue structure among the Swedish media companies, mainly from financing through advertising to financing through subscriptions. This is evident in the Swedish TV market in particular, where the revenues from subscriptions are increasing, while the revenues from advertising have decreased. In terms of media expenditures, an average Swedish household spent nearly 17 000 SEK on media in 2014 (media technology purchases not included) (Facht 2016).

The dissemination and use of the media on digital platforms assumes that there is an infrastructure and that the population has access, the knowledge and the financial means to use it. Sweden has a well-developed ICT infrastructure, affordable ICT access, high Internet usage and both formal and informal education on media literacy.

In March 2015, the Ministry of Culture and Democracy initiated a media inquiry aiming to analyse the need for new media policy tools and how to promote opportunities for the Swedish public to access journalism that is characterised by diversity, balanced reporting, quality and depth, regardless of where in Sweden you live (Dir. 2015: 26). There is a long way for proposals to become media policy implementations. However, the media inquiry could also be seen as confirmation of a currently and most interesting formative momentum of the Swedish media landscape.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The implementation of the 2016 Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM2016) in Sweden shows a generally low risk for media pluralism in the country: 10% (2) of the indicators demonstrate high risk, 10% (2) of the indicators demonstrate medium risk and 80% (16) of the indicators demonstrate low risk. Due to lack of specific thresholds in media legislation to prevent a high degree of concentration of ownership, Sweden scores high risk on two of the Market Plurality indicators, Concentration in media ownership (horizontal) and Commercial & owner influence over editorial content, and medium risk in ‘Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement’. Second indicator that scores medium risk in the MPM2016 for Sweden is Access to media for minorities, from the Social Inclusiveness area.

In sum, the MPM2016 instrument shows warnings in terms of the market plurality. But the overall state of media pluralism in Sweden should be considered as good.

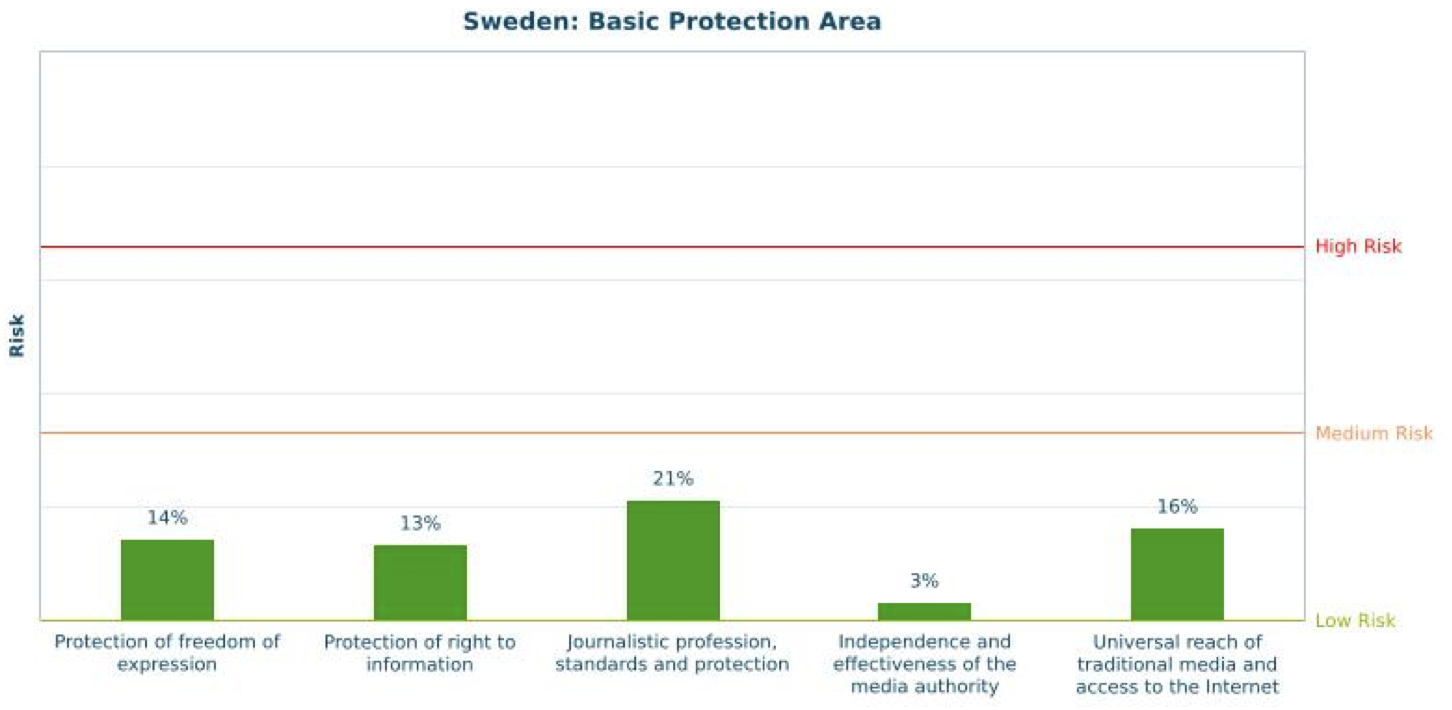

3.1. Basic Protection (13% – low risk)

The Basic protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Sweden scores low risk in the Basic protection area, where all five indicators score between 3% and 21%.

The Swedish media system has a long regulatory tradition for media freedom. There are two constitutional acts relevant to free speech for the Swedish media: the Freedom of the Press Act (SFS 1949:105) and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression (SFS 1991:1469). Together with the constitutional law that regulates individual freedom of expression, these acts constitute the foundation of the Swedish media system.

Freedom of expression is explicitly recognised in the Swedish Constitution since 1991 and there are relatively few cases of freedom of expression violations in Sweden in recent years. Instead of systemic violations, it is more correct to speak in terms of few exceptional cases. The indicator ‘Protection of freedom of expression’ scores a 14% risk.

Sweden scores generally low on the indicator Protection of right to information. The legal provisions to protect the right to information are clearly defined. So are the restrictions on grounds of protection of privacy and confidentiality. However, there are at the same time some indications of poor implementation even though it is not possible to judge whether deliberately or due to ignorance of the officials. In total, Sweden scores a 13% risk for this indicator.

The indicator Journalistic profession, standards and protection has the highest risk score (21%) within the basic area. The general view is that the conditions the Swedish journalists operate in are among the most favourable in the world (RSF 2016). The composite risk level for this indicator is also generally low. However, there are some notable blemishes related to journalistic protection. Statistics from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention shows that more than 30% of the journalists in Sweden are harassed and threatened each year because of their work as journalists (BRÅ 2015). This is confirmed by the results from the Swedish Journalist Panel at the University of Gothenburg where 80% of the journalists also answered that email is the most common mediation of abusive comments and threats. Moreover, the results show that the more visible and profiled the journalist is, the more vulnerable to threats. Particularly vulnerable are the journalists working on crime and justice where 60% stated that they have been threatened in the last twelve months. (Löfgren-Nilsson & Örnebring 2015).

The indicator ‘Independence and effectiveness of the media authority’ has the lowest risk score (3%) in the Basic protection area. Sweden has effective regulatory safeguards for the independence of the Swedish Press and Broadcasting Authority, limiting the risk of political and commercial interests. The explicit objective of the media authority is to support freedom of expression, diversity, independence and accessibility.

Sweden scores low risk on the indicator Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet (16%). In addition to the Swedish Radio and Television Act (SFS 2010:696) and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression, the universal coverage of both the PSM and private media is regulated in the broadcasting licences. Together with a well-developed infrastructure and affordable ICT access, this guarantees a universal coverage of traditional media and access to the Internet in Sweden.

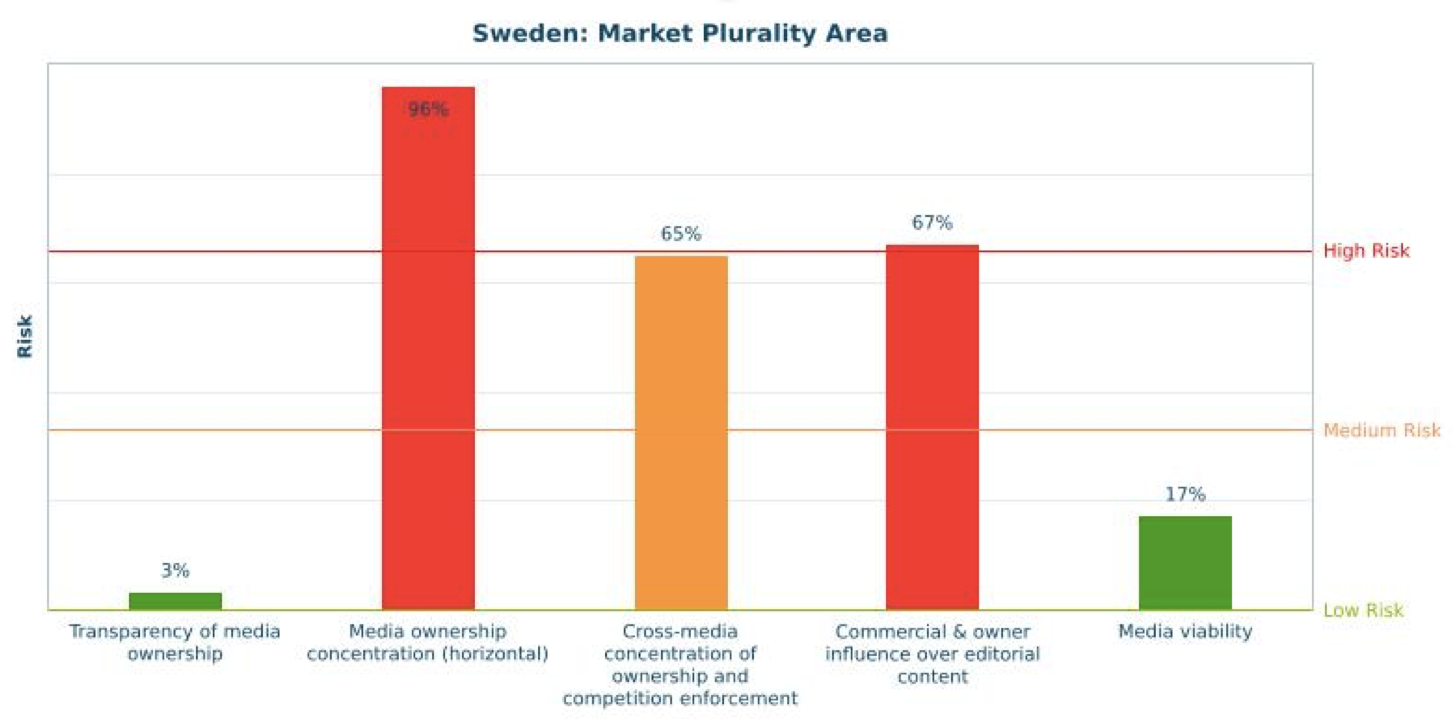

3.2. Market Plurality (50% – medium risk)

The Market plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Overall, Sweden scores medium risk in the Market plurality area, where the five indicators score between 3% and 96%. Sweden scores high risk on the indicators ‘Media ownership concentration (horizontal)’ (96%) and Commercial & owner influence over editorial content (67%). The media sector is regulated on the basis of the general Swedish Competition Act. Additionally, ownership concentrations in the media sector are regulated in the Radio and Television Act and in the broadcasting licences.

The indicator Transparency of media ownership has the lowest risk score (3%) in the ‘Market plurality’ area. Sweden has no specific regulations on transparency for media companies as such. Instead, the media companies are included and constrained to follow the general regulations in the Swedish Law of Financial Relations, the so-called Transparency Act (SFS 2005:590). This means that all Swedes can access the annual reports of the Swedish media companies, which also include information on ownership and are available on their websites.

Sweden scores low risk on the indicator Media viability (17%). A growing proportion of the revenues for Swedish television come from digital services. It should also be noted that the national television broadcaster TV4 is one of the most financially successful television broadcasters in Scandinavia, and currently improving its financial results. As a result of the fundamental and ongoing restructuring of the advertising markets in recent years, the business model of the Swedish newspaper industry has been put under severe pressure. Since 2012, the printed newspaper is no longer the largest advertising platform on the Swedish market – the Internet is. However, many Swedish newspapers have pay walls for online news, which helps explain why Sweden has one of the highest rates of payment (20% in the last Digital News Report 2016 from Reuters Institute) (Westlund 2016).

The indicator Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement produces a medium risk score (65%). There are no specifications on cross-media ownership specifically aimed at media companies. Instead, cross-media ownership is covered by the Swedish Competition Act (SFS 2008:579) through two main provisions: (1) Prohibition of anti-competitive cooperation; (2) Prohibition of the abuse of a dominant position. The Swedish Competition Act also contains restrictions on: (1) Anti-competitive sales activities by public entities; (2) Control of concentrations between undertakings.

Sweden scores high risk on the indicator Commercial & owner influence over editorial content (67%). All members of the Swedish Union of Journalists (SJF) agree to follow professional rules. Violation of these rules can be notified within three months of the event at the journalists’ ethics committee. On the other hand, one of the current most pressing issues concerns content marketing and where to draw the line between advertorials and editorial material. This is clearly a challenge for the Swedish media to manage as it creates difficulties for ordinary people to see the difference between advertorials and editorial material..

Sweden also scores high risk on the indicator Media ownership concentration (horizontal) (96%). The Radio and Television Act and the broadcasting licences regulate and prevent high levels of horizontal concentration of ownership in the media sector. Furthermore, the media sector is regulated on the basis of the general Competition Act. However, the Radio and Television Act contains no clearer criteria than the wording: ‘ownership may not change more than to a limited extent’. Consequently, it is up to each authority to estimate what this really mean (also note that this formulation has no constitutional support).

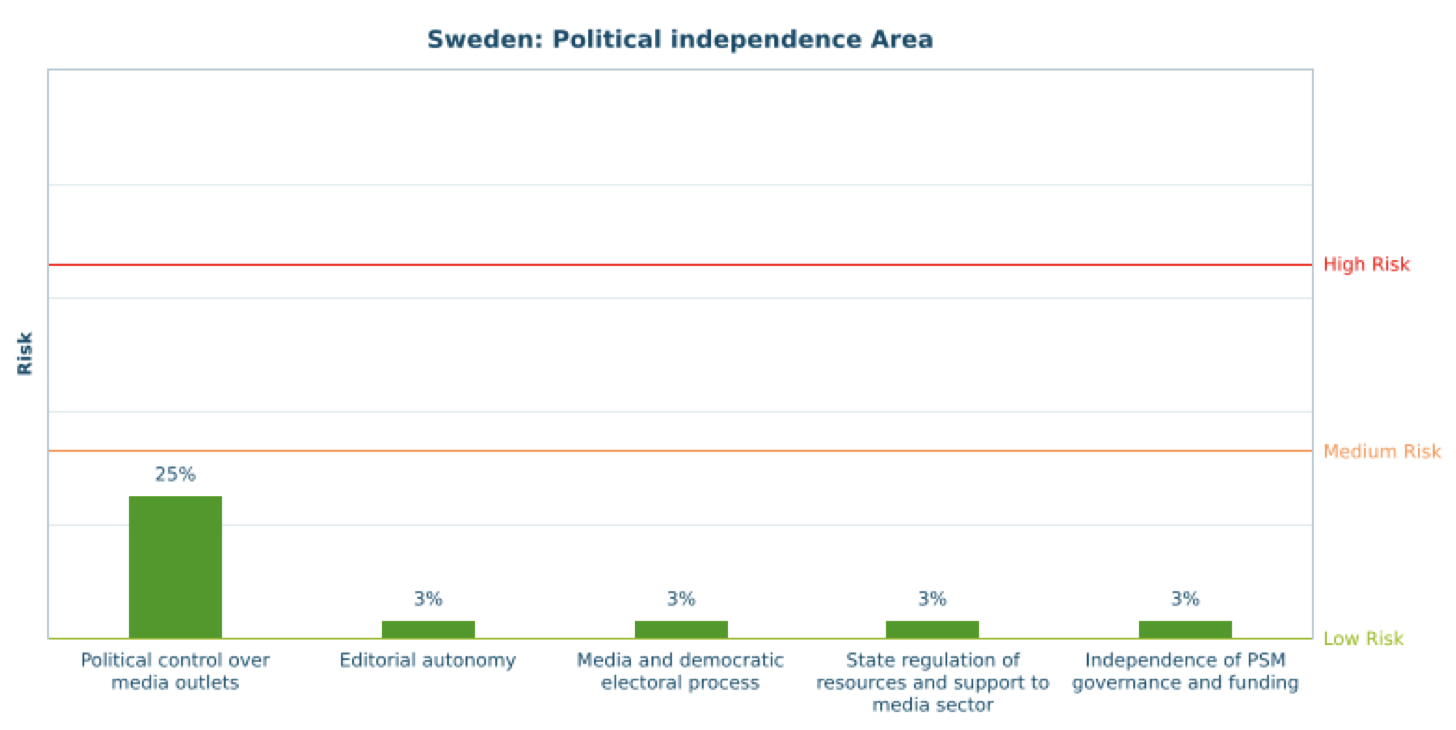

3.3. Political Independence (7% – low risk)

The Political independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Sweden scores low risk in the Political independence area, where all five indicators score between 3% and 25%.

The indicator Political control over the media outlets scores low risk in Sweden, but the 25% of risk makes it the biggest concern within this area. The relatively high score is related to the lack of regulation, rather than to actual malpractice. Moreover, there are no examples of conflicts of interest between media owners and ruling parties, partisan groups or politicians.

The indicator Editorial autonomy scores a low risk (3%). Autonomy in appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief is regulated by the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act. Additionally, a large number of media and journalist organisations have jointly developed a number of self-regulatory/voluntary codes of conduct for stipulating editorial independence, which the majority of Swedish media are following. There are also no indications of informal political interference in appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief or of parties or politicians trying to influence the editorial content.

Media and democratic electoral process also has a low risk score (3%). The lack of concern in relation to this indicator is confirmed in a number of annual evaluations of Swedish media news content. The Media Election Survey conducted every parliamentary election in Sweden since 1979, shows that both PSM and commercial media generally offer proportional and non-biased representations (Asp 2011). The latest report shows that Swedish PSM channels are fair, balanced and impartial (Asp 2015). It also shows that plurality has decreased in the commercial channels and increased in the PSM channels between 2013 and 2014.

Sweden scores a low risk on the indicator State regulation of resources and support to the media sector (3%). The implementation of the so-called ‘telecom package’ in Swedish legislation is a high priority for the Swedish government. The legislation on spectrum allocation is also implemented effectively. However, a country with the kind of topography and demographics of Sweden, there is a need for greater flexibility in technology than what is the case today, to carry out the deployment of high speed broadband in the most efficient way possible. The direct state subsidies are distributed to media based on fair and transparent rules. However, most media experts agree that the Swedish press subsidy system is old, outdated and in need of revision.

The indicator Independence of PSM governance and funding acquires a low risk score (3%). The broadcast licence regulates the operations of the Swedish PSM broadcast media in terms of independence from the state and from different economic interests. Media independence is also regulated by the Swedish Radio and Television Act and the Freedom of Expression Act. The appointment procedures are well defined in law and provide for the independence of the Swedish PSM boards and management. However, the procedure allows political oversight. The PSM boards are appointed by the PSM Management Foundation (Förvaltningsstiftelsen), which in turn is appointed by the government on the proposal from the political parties in the Swedish parliament. There are at the same time no indications or any other examples of conflicts concerning appointments or dismissals of managers and board members of the Swedish PSM.

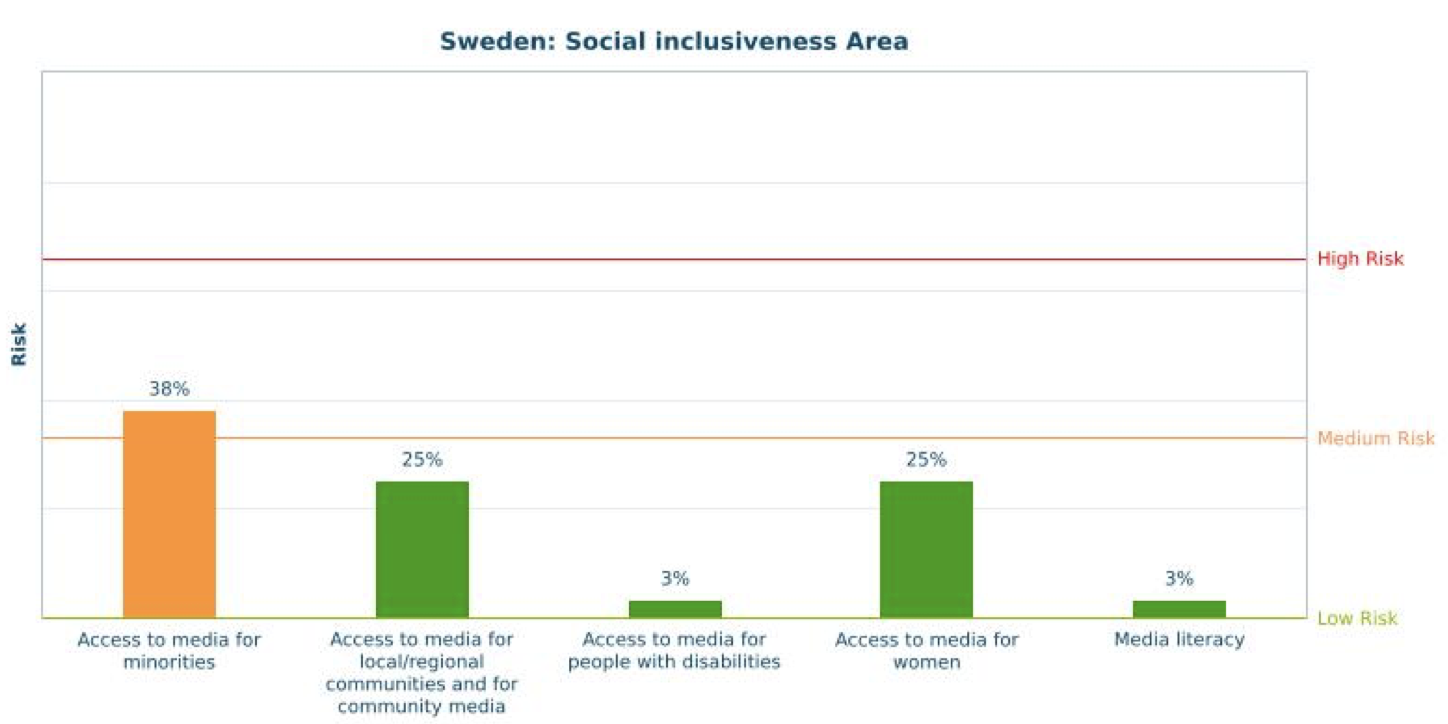

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (19% – low risk)

The Social inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The ‘Social inclusiveness’ area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

On average, Sweden scores low risk in the Social inclusiveness area, where the five indicators score between 3% and 38%.

The indicator Media literacy produces a low risk score in Sweden (3%). In Sweden the field of media and information literacy is currently in a state of transition. The Swedish Media Council invests a lot in including informal education on media literacy in schools and libraries. For example, they produce information and pedagogical material to be used by parents, educators and people who meet children and young people in their profession. The majority of Swedish people use the Internet on a daily basis and have at least basic digital skills. At the same time, Sweden is struggling with the same challenges as many other countries in the EU, to really reach out with information and knowledge to peripheral groups (e.g. language, culture etc.).

Sweden scores low risk on the indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media (25%). In Sweden, the independence of community media encompasses both diversity in media content and media providers. PSM also has a specific agreement to offer a diverse range of programmes (AV 2015). These should reflect the diversity of the entire country and characterised by a high level of quality, versatility and relevance and be accessible to all.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scored low risk in Sweden (3%). Sweden has a strong tradition in policy-making on access to media content by people with disabilities. However, the policy is not explicit about quality: you can for example turn on or turn off the subtitles but you cannot customise further[2].

Sweden scores low risk on the indicator Access to media for women (25%). The Swedish law on equal rights (SFS 2008:567) is reactive and can especially be used when individuals believe they have been disadvantaged. In addition to protection against discrimination there are also various promotions, such as access to a good education for everyone[3]. In the media sector, there are instead more explicit requirements for example that program content should promote diversity and equality (which is usually interpreted as a balanced representation of women and men)[4]. The PSM SVT has a comprehensive gender equality policy covering both personnel issues and programming content. At the same time, the data from the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) shows that the share of women as subjects and sources in news, as well as among news reporters, is still rather low in Sweden (around 30%).

Sweden scores medium risk on the indicator Access to media for minorities (38%). First of all, the Swedish broadcasters have a major responsibility to take into account the needs of both physically challenged peoples as well as the national linguistic and ethnic minorities. According to the Swedish PSM Broadcasting Licence, the Swedish broadcasters are expected to give minority media access to media platforms and not least to improve accessibility.

In Sweden access to airtime on PSM channels for social and cultural groups are guaranteed in practice, but whether the access to airtime is adequate or not varies between social and cultural groups. The Swedish PSM broadcasting licences contain conditions relating to airtime of the five minority languages: Sámi, Finnish, Meänkieli, Romani Chib and Yiddish. SVT has increased the airtime for Sámi, Finnish, Romani and Meänkieli from 559 hours in 2013 to 636 hours in 2014. With an agreement with SR and UR, SVT broadcast news in Finnish and Sámi. SR broadcasts news programmes in Romani Chib and Meänkieli. One of the conclusions of the Swedish Media Inquiry was also that the obligation for PSM broadcasters to give airtime to the national minority language should also include the largest immigrant languages in Sweden such as Arabic, Serbo-Croatian, Kurdish and Persian (SOU 2016:30).

4. Conclusions

The implementation of the 2016 media pluralism data collection in Sweden shows a generally low risk for media pluralism in the country. However, there are particular issues that blemish the Swedish low risk score. One such issue relates to the Market plurality area and the concentration in media ownership.

The Swedish media system is concentrated and much of this can be explained by the small size of the Swedish media market. However, media pluralism and the opportunity for the Swedish people to gain unconstrained access, generate and share a wide range of information are essential to Swedish democracy. It has never been easier for the Swedish people to access, generate and share information. However, as the concentration in media ownership increases and the flow of information expands, it has never been easier for the Swedish people to avoid information. There is a risk of an echo chamber effect reducing understanding of other people’s perspectives and opinions, and increasing polarisation.

Another issue relate to the Basic protection area and the standard and protection of the journalistic profession. The composite score for this area is low risk. But if we look beyond the overall score it is apparent that the safety of a journalist is not even fully guaranteed in a highly developed democratic country as Sweden. Instead, harassment and intimidation form very efficient ways to silence Swedish journalists. We need to diversify our understanding of journalistic autonomy and add a dimension of ‘external pressure and threats’ into media plurality evaluations (such as the MPM tool) in the future.

The Swedish media landscape is undergoing an extensive transformation. This transformation is characterised by a convergence of media services. Swedish traditional media is more and more intertwined with the Internet. This transformation presents both opportunities and challenges in terms of media plurality. Although it has never been easier for people to access, generate and share information, this transformation also increases the demands on people’s abilities to search, sort, critically analyse and process information.

References

AV 2015. Anslagvillkor för 2016 avseende Sveriges Radio AB. Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

Facht, Ulrika. 2016. MedieSverige 2016. Göteborg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg.

Dir. 2015:26. (Sweden) En mediepolitik för framtiden. [A media policy for the future]. Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

RSF 2016. 2016 World Press Freedom Index. Paris: Reporters Without Borders.

SFS 1949:105. Tryckfrihetsförordning. [Freedom of the Press Act] Stockholm: Ministry of Justice.

SFS 1991:1469. Yttrandefrihetsgrundlag. [Law on Freedom of Expression] Stockholm: Ministry of Justice.

SFS 2010:696. Radio- och tv-lag [Radio and Television Act] Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

BRÅ. 2015. Hot och våld. Om utsatthet i yrkesgrupper som är viktiga i det demokratiska samhället. [Threats and violence. On vulnerability in professions essential in a democratic society]. Rapport 2015:12.

Löfgren-Nilsson, Monica & Henrik Örnebring. 2015. Journalism under threat: Intimidation and harassment of Swedish journalists.

SFS 2005:590. Lag om finansiella förbindelser [Law of Financial Relations] Stockholm: Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

Westlund, Oscar. 2016. Digital News Report 2016: Country report – Sweden. Oxford: Reuters Insititute.

SFS 2008:579. Konkurrenslag [Competition Act] Stockholm: Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

Asp, Kent. 2011. Mediernas prestationer och betydelse. Valet 2010. [The media performance and importance. The election of 2010]. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg.

Asp, Kent. 2015. Svenskt medieutbud 2014 [The Swedish Media Output in 2014]. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg.

SFS 2008:567. Diskrimineringslag [Discrimination Act]. Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

SOU 2016:30 Människorna, medierna och marknaden [The people, the media and the market]. Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Mathias | Färdigh | PhD | JMG, University of Gothenburg | X |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Peter | Skyhag | Information strategist | Swedish Union of Journalists |

| Oscar | Westlund | Associate Professor | JMG, University of Gothenburg |

| Jocke | Norberg | Strategist | Sveriges Television |

| Jesper | Strömbäck | Professor | JMG, University of Gothenburg |

| Gunnar | Springfeldt | Former VP of development | Stampen Media Group |

| Christoffer | Lärkner | Desk Officer | Ministry of Culture, Government Offices of Sweden |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] This is an extract from the interview with Mattias Hellöre, board member of Sveriges Dövas Riksförbund. Interviewed by email by the Swedish country team on 7 June 2016.

[3] This is an extract from the interview with Eva-Maria Svensson.

[4] This is an extract from the interview with Gunilla Hult.