Download the report in .pdf

English

Author: Željko Sampor

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Slovakia, the CMPF partnered with Željko Sampor (Pan-European University), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

Preliminary stakeholders meeting has been held in September 2016 with Creative Industry Forum, that joins legal persons who work in the sector of creative industry (individual member), or unite legal and natural persons working in the area of creative industry (collective member). An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

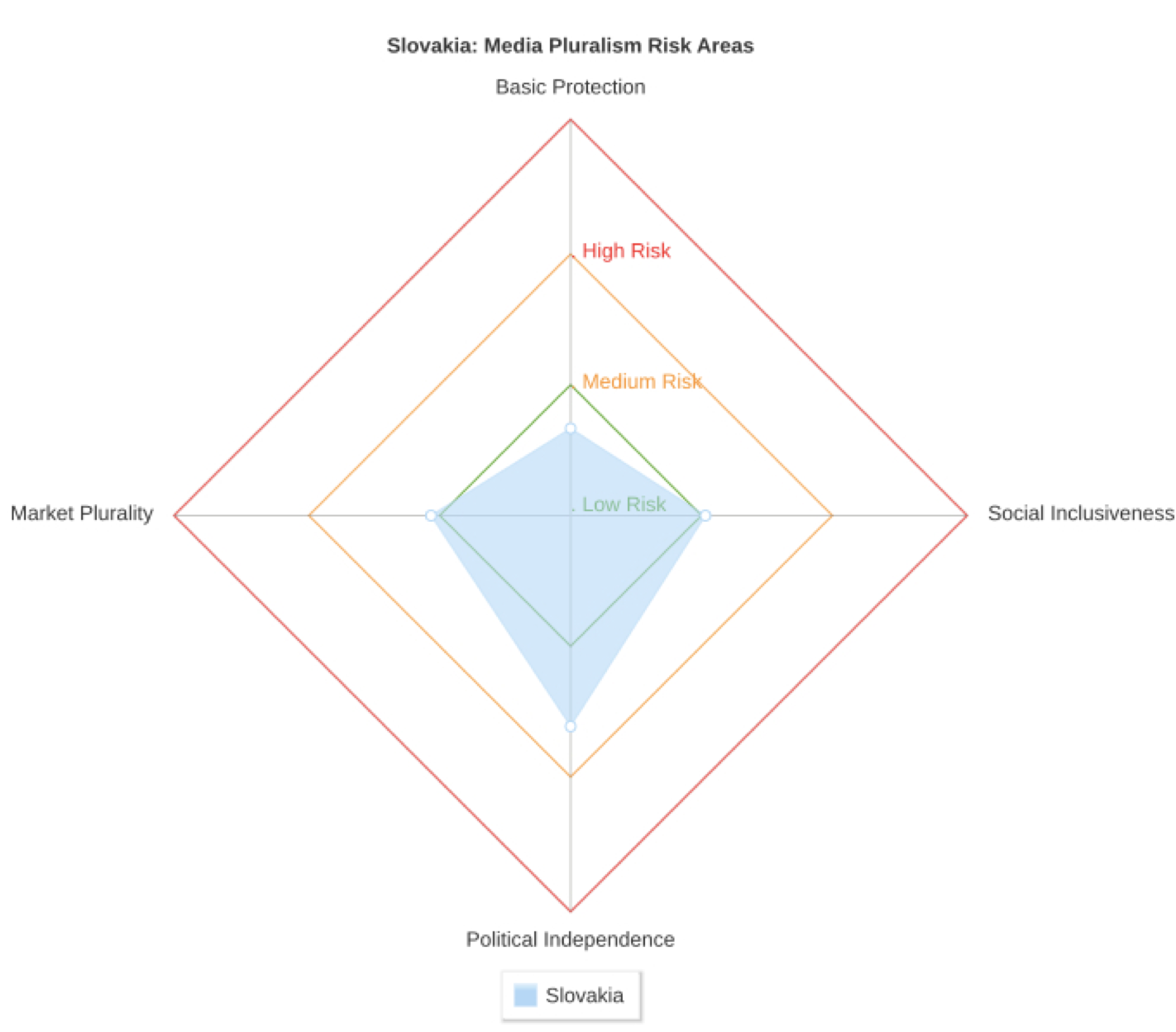

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Territory of Slovakia is 49,000 square kilometres and with a population of slightly less than 5.5 million. Though the official language of Slovakia is Slovak the other languages belonging to traditional national minorities are also spoken, mainly Hungarian, Czech, Roma, Croatian, Rusyns, Ukrainian and Polish. This relates to nationality structure where majority are Slovaks (86%) with the most numerous national minority Hungarians (10%) and the Roma minority.

Both the religious and nationality structure is split between the regions so it does not form one homogeneous structure. Also vast majority of inhabitants live in small towns and villages. Out of 2,933 settlements only two have over a 100,000 inhabitants (Bratislava and Košice) while only 138 are listed by the Government office as cities or towns. The size, population and regional fragmentation reflects both on political, economic and media landscape.

The main industry engine is the automotive industry, with Slovakia being currently biggest producer of cars per capita in the world, according to International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. Major manufacturers are Volkswagen, Peugeot Citroën and KIA. Other branches of industry include metallurgy (mainly U.S. Steel in Košice), chemical industry, agriculture and tourism. The creative industry, that includes also media, together with knowledge based economy, thus far makes only fraction of the economy, but it is seen by both the government and industry as a prospective area for growth. According to Ministry of Labour the average unemployment is above 9% with declining tendencies. The economic situation could be described as stable with slow but growing tendencies.

The political landscape is characteristic by one major party that is currently holding also the position of the head of government. At the same time, this is the only party in the Parliament that identifies itself as a left wing party (SMER), the other two coalition parties identify themselves centre right (MOST-HID) and national right (SNS). The opposition is composed of variety of those identifying themselves as right wing parties, including far right, with exception of one declared liberal party. Also as a rule new parties emerge at every election that manage to get into parliament and even though there is variety in number of parties, with exception of economic programs, the general political leaning is towards right.

Six dailies including two tabloids and two nationwide press agencies represent the press landscape, with various community and minority prints. As for broadcasting the dual system is represented by public service media company on one hand and two major players TV Markiza group and TV JOJ group on another. Similar situation is in radio broadcasting, while what’s common is that PSM has an advantage of owning of both radio and TV programming service. This is not possible for private broadcasters. Various community, minority and municipal media also exist but on much smaller scale.

While television digital terrestrial broadcasting transition has been completed the radio terrestrial digital broadcasting is virtually non-existent, with all radios still broadcasting via analogue. The on-demand services are present on the market and current major media players are trying to expand to new platforms in search for new revenues.

Consumption of foreign-based media is limited due to the language; however the Czech based media still retain their traditional presence on the market because of both common historical background and language similarities. This applies both for traditional media such as television broadcasting and online media and news sources. Digital news consumption is on the rise both as a result of expansion of traditional media to online platforms, as well as rise of new media platforms. According to M. Velšic, only 4% of population in the age between 18 to 39 does not receive information from digital sources at all.

Major regulatory body for content regulation is the Council for Broadcasting and Retransmission that is also in charge of licensing with some shared competences with the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (ex-Telecommunication office). From the point of self-regulation, the most important and with longest standing is the Slovak Advertising Standards Council and as an emerging coordinator of the industry actions in the field of policies is the Creative Industry Forum.

With declining influence of the Slovak Syndicate of Journalists the role of various NGOs and auto-regulation has increased as both guardians of ethics in journalism and promotion of importance of plurality in media.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Slovakia scored low risk on several areas such as access to media for people with disabilities, media literacy, media and democratic electoral process and overall basic protection. This is due to both newly implemented measures, as in the case of people with disabilities, or standing regulation that contains safeguards, such as judicial review, and over time application of these safeguards has proven effective. These include, among others, good legal definition of protection of sources for journalist and court remedies available when access to information is denied by public bodies.

Market plurality is within the medium risk score. There are safeguards in place regarding media concentration and cross ownership and sanction mechanisms that are in place and are implemented; especial regarding radio and television broadcasters. On the other hand, there is sometimes lack of specific data and statistics regarding market shares when assessing the situation.

The most critical area is political independence. High risk score results from lack of protection of editor in chief and influence of local government over local private media that are often dependent or owned by the municipal governments. Also, prevailing problem appears to be absence of safeguards regarding secure and transparent funding to Public service media; and more specific rules on how these funds are used and overall independence from potential political influence of the PSM.

Medium risk score shows both progress and drawback in certain areas. Notably in representation of minorities, where traditional minorities appear to have well establish place in media representation; however other minorities such as new language minorities, new national minorities or gender minorities have very little or no access to representation, especially in the PSM. Same applies to access to media and representation of women in media. Overall regarding medium risk scored indicators that situation is somewhat borderline and if measures are not taken to improve the situation there is tendency for situation to decline further. This applies especially to all indicators in Social Inclusiveness but also in regard to Market plurality.

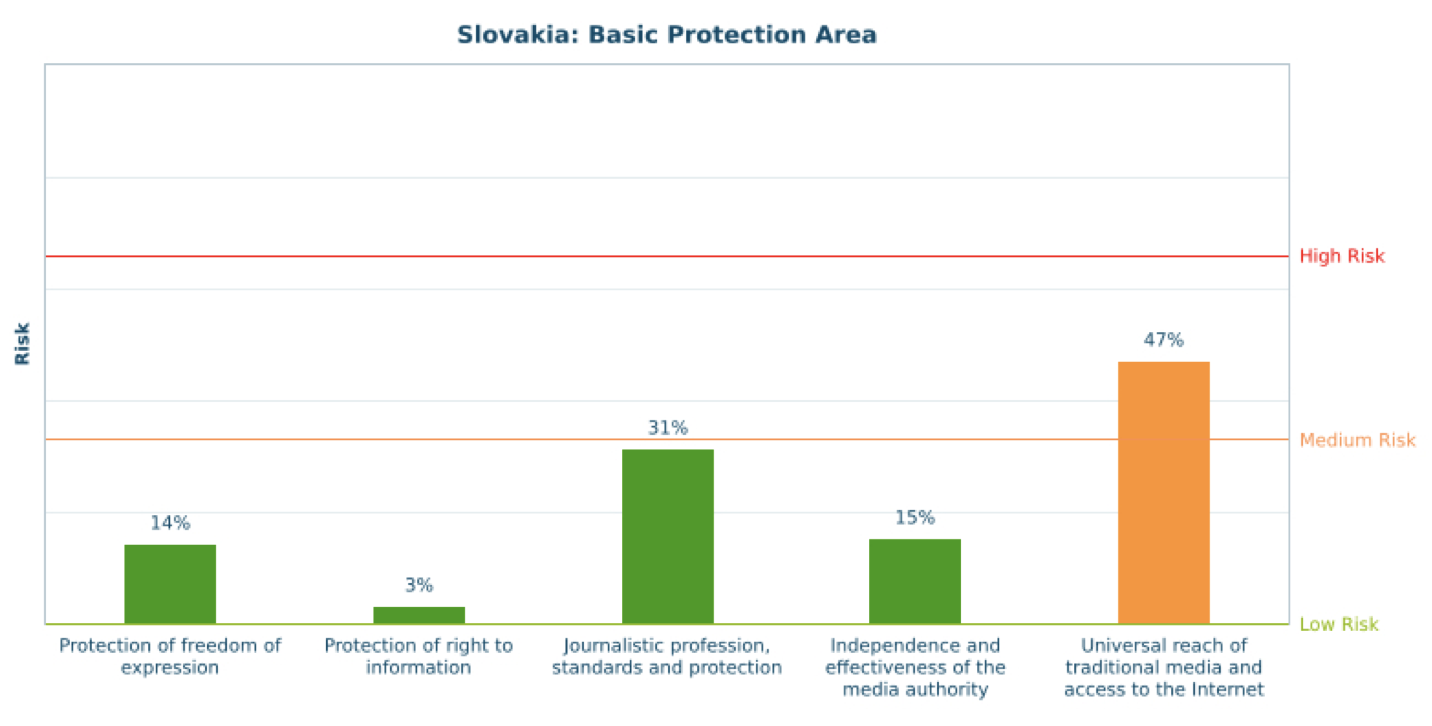

3.1. Basic Protection (22% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The positive outcome of the Protection of freedom of expression (14%) and protection of right to information can be attributed mainly to the active role of civil society and good legislative provisions that provide remedies for both right to access to information and protection of source, as well as constitutional provisions and long standing judicature of the ECHR and its implementation. Although there are still some difficulties mainly regarding abuse of freedom of expression in the form of hate speech via social networks.

As for the Protection of right to information (3%), even when public bodies refuse to provide information on no legal grounds, the court of appeal process provide effective remedy, where even no reply from the public body can be appealed as a ‘fictitious’ decision on non-providing the information. These mechanisms include Court proceedings, which are used on a regular basis and provide consistency of judicature therefore lowering the risk of violation in access to information. The Court of appeal proceeding functions effectively both on ordering information to be released and filtering (halting) the misuses of this right. On the other hand, the relationship between politicians and journalists, e.g. lack of willingness to communicate during press conference, is still occasionally present. However these information still may be sought formally via written request, where the above mentioned mechanism can be used.

Another reason for low risk scoring can be attributed to the legal provision that source protection is based on. It is the de facto the same as the one for confession (for priests). This means that they cannot be forced by courts to testify about the identity of their source; it is a legal exemption from an obligation to provide testimony. The only circumstances where this is exempt is in situations in which the law imposes general obligation to prevent crime / inform about crime, such as in the case of planned terrorist attacks.

When it comes to the Journalism profession standards and protection (31%), the low risk level reflects mainly the auto-regulation and outspoken actions of journalists. As an example, in 2016, when the head of the self-governing county (VUC) M. Kotleba, also elected MP for the far right nationalist party, has banned the access of some journalists to his press conferences, consequently the Slovak Syndicate of Journalists (SSN) has publicly supported journalists. In addition, the TASR (national press agency) is participating with publishing their decisions, thus trying to maintain via public scrutiny basic standards of journalism.

The low risk indicator on independence and effectiveness of the media authority (15%) results from the way the Broadcasting Council is composed. Membership, including a rotation system, eligibility, terms, termination etc. are provided by the law and these legal provisions are not tamper with providing certain level of security and predictability. Furthermore, each decision of the Broadcasting Council can be subjected to judicial review. Moreover, the legislative or other branches of government do not exercise any direct control over the Broadcasting council, apart from nominating its members, and Council’s decisions are reviewed by an independent court. The decisions and actions of the regulatory authority can be assessed as fairly independent.

Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet (47%) scored medium risk mainly because of technical difficulties resulting from the landscape and the way population is spread. There is a tendency to compensate for this by combining various ways of broadcasting. In addition, the PSM Radio still has its analogue network both on FM and AM frequencies; plus online broadcasting and via mobile phone apps. Currently approximately 81% of households in Slovakia have access to internet

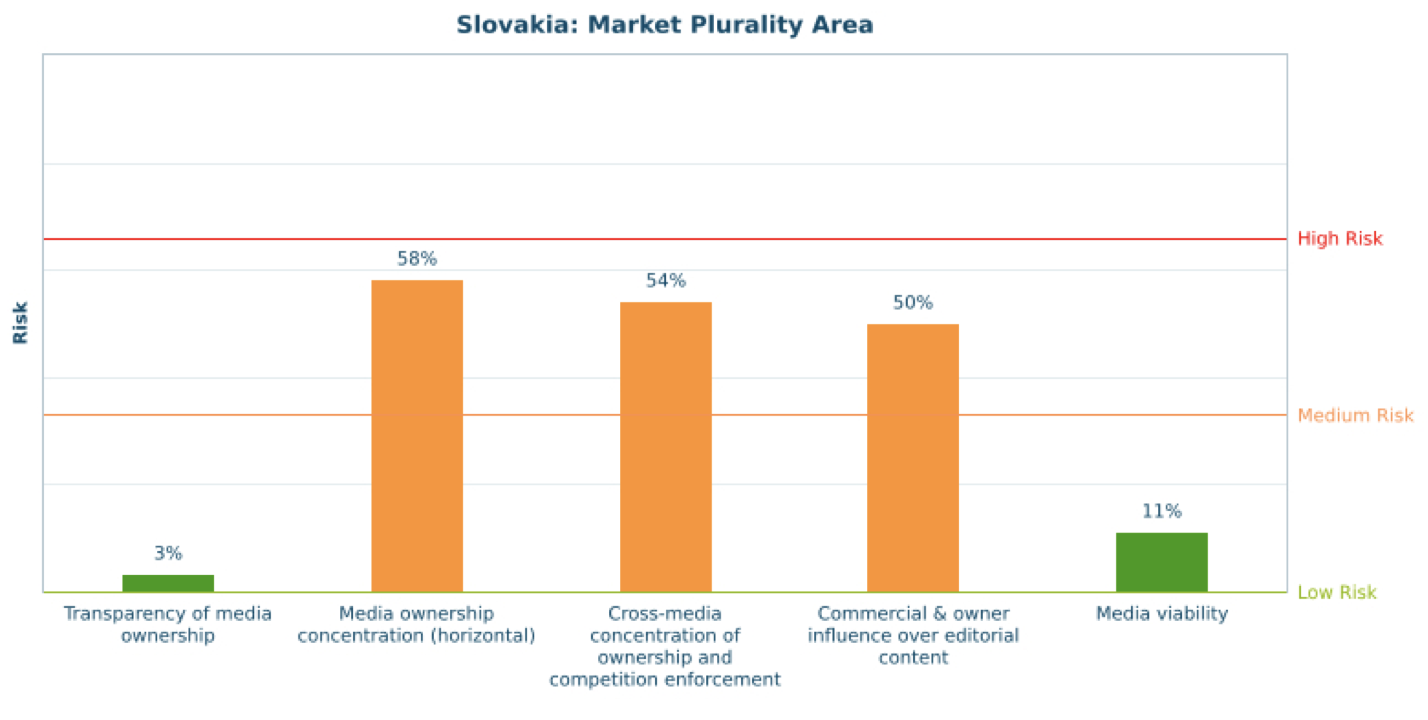

3.2. Market Plurality (35% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a low risk (3%). This transparency is provided via obligation that the Ministry of Culture must be informed about ownership structure in relation to every stakeholder that has reached at least 20% stake; this information is publicly accessible. As for Radio and TV any changes in the ownership structure requires a change of license and must be declared to the Broadcasting Council. The fact that the Company register is publicly accessible makes ownership transparent to a degree; this results in a low risk score, especially taken in the context of sanctions related to non-disclosure of the ownership structure of the broadcaster to the Broadcasting Council.

Media ownership concentration (horizontal) medium risk (58%) can be attributed to general lack of accessible statistics data that would enable better evaluation in comparison of overall market shares among major players – considering the size of the market the legal provision of horizontal concentrations are rather strict. It is important to emphasize that one legal entity or one natural person can be granted at most one licence to broadcast a television programme service or one licence to broadcast a radio programme service.

The medium risk score on cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement (54%) can be attributed to a similar reasoning as the one for the media ownership concentration (horizontal). Slovakia has strict rules in respect of horizontal and cross media concentration and specific safeguards regarding vertical concentration. The publisher of a periodical that is published at least five times a week and is available to the public in at least half of the territory of the Slovak Republic cannot simultaneously be a licensed broadcaster on the multi-regional or national levels. Moreover, all forms of cross ownership or personal connection between the broadcaster of a radio programme service and the broadcaster of a television programme service to each other, or with a periodical press publisher on the national level are prohibited. This provision excludes the Public Service Media which is a single company broadcasting both radio and television.

When dealing with concentrations the higher involvement of competition authorities is generally expected. Regarding how the system is set in Slovakia, it is questionable what would be the contribution of this higher enrolment, considering the rather strict sanctions for breach of rules, ranging from financial fines to revoking of licence.

Commercial & owner influence over editorial content scored 50% especially because there are only general provisions of the Labour Code that apply also to journalists, and the editor-in-chief is not a legal term in Slovakia, meaning that no media law mentions him/her and therefore there are no special legal safeguards. This indicator takes into consideration also aspects of advertorials and therefore of Slovak Advertising Standards Council actions and cross promotion and surreptitious advertising enforcement. As one of the oldest self-regulation body in Slovakia, Advertising Standards Council acts promptly and its decisions are generally adhered; its panel is made of independent experts and the industry. This gives to this indicator overall medium risk score.

The media viability indicator low risk score of 11% is to be attributed mainly to the growth in investment in to media in the post financial crisis period. Nevertheless, there are no data publicly available that would enable to see overall revenues and consequently split by source, all major traditional media attempts to expand to online in order to find new sources of revenues (such as VOD, app provided services, e-shops etc.).

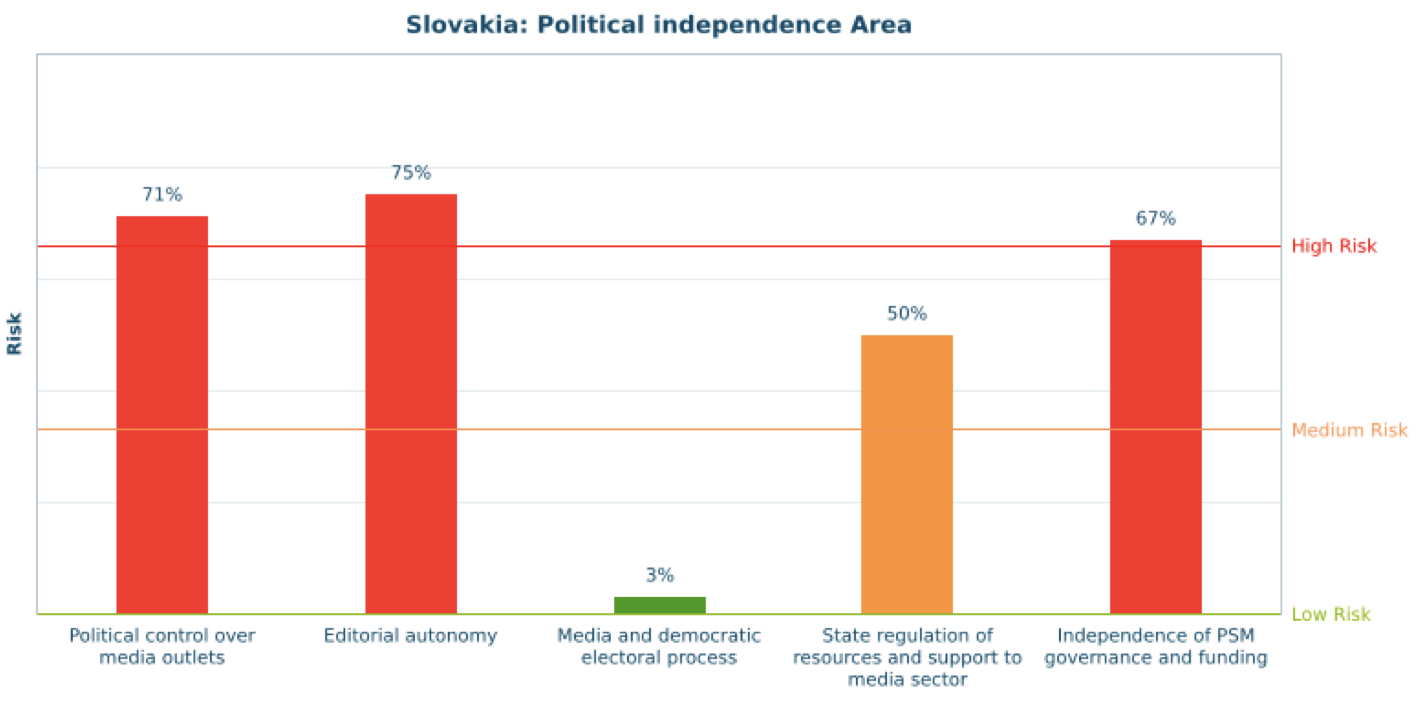

3.3. Political Independence (53% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Political Independence is the area that scores the highest risks within the Monitor for Slovakia. Only the indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scored very low risk, due to the fairly complex set of legal rules prompted with sanction mechanism.

High risk score for the indicator on Political control over media outlets (71%) is in general due to the issues with local/regional/municipal media. According to the NGO Institute for public affairs (IVO – Inštitút pre verejné otázky) report, the question of objectivity and balance of the news reporting in local media, that are de facto owned by municipal authorities in the period before elections, is a long term unsolved problem. As an example we can use town Galanta where the chairman of the editorial board of the periodical that is published by the town, while member of the board, became also member of the campaign team for the coalition of political parties that was the election team of the mayor; this could be viewed as an example of direct political influence, or at least link, over media. A different example was in capital Bratislava, where owner of the publisher of the local newspaper, that was at the same time candidate for the mayor of the borough Bratislava old town, merged election campaign with the advertising campaign for the local newspaper; he won the elections (see IVO election report, p. 139 and 140). Financial dependence of the local media on the municipal governments is obvious not only in the media that are owned by (directly or indirectly) the municipalities (see Broadcasting Council Report 2015, appendix 4), but also in relation to the commercial local media; as it is confirmed by the situation in capital Bratislava where the local government directly financially supports two local TV stations. While at least one of these media is directly personally linked with governing political parties via management positions of candidates for MP (see Nesrovnal rozdelil PR budget. Dal aj televízii zmietanej v konflikte záujmov). Financial dependency on local governments is confirmed also by the association of the regional TV stations, RegionTvnet, that stated: ‘the incentive for creation of association is community wide unappreciation of the activities of the local media, that are on the Slovak media market for 20 years and majority of them are often perceived negatively because they are completely dependent on the municipal governments’.

The question of political control is inherently connected with the question of Editorial autonomy, giving this indicator also a high-risk score (75%). Not all major players signed up to the Ethical code of the journalist. Except PSM there is no obligation for private media to have any self-regulatory measures. At the same time there is neither self-regulatory common statute for media under self-regulatory platform nor self-regulatory body with any significant effect.

The legislation as well as implementation of coverage of electoral process produced no major incidents. That refers political advertising, space given to political parties as well as media coverage; as such. Also, regulatory bodies in charge, mainly Broadcasting Council and Electoral commission, are swift to react on any breaches; resulting in low risk score of 3% for the Media and democratic electoral process.

The indicator on State regulations of resources and support to the media sector scored a medium risk (50%) mainly because of the lack of fair and transparent rules and practices on the distribution of state advertising to media outlets. In this regard even the Act governing public tenders excludes the advertising placement from public tenders (public procurement). On the other hand the decisions about state advertising are made based on management of public finance rules that are to be taken in to consideration also in the case of advertising and media placement. With 20 million Euros redistributed via advertising while no clear rules of distribution are set, the result of this indicator is the result of two extremes taken into account.

The high-risk score (67%) for the Independence of PSM governance and funding indicator is the result of lack of transparency of cash flow from various public (licence fees, contract with the state) and private funds (advertising), lack of financial guarantee for the PSM and ease of access of political influence to its governing structure.

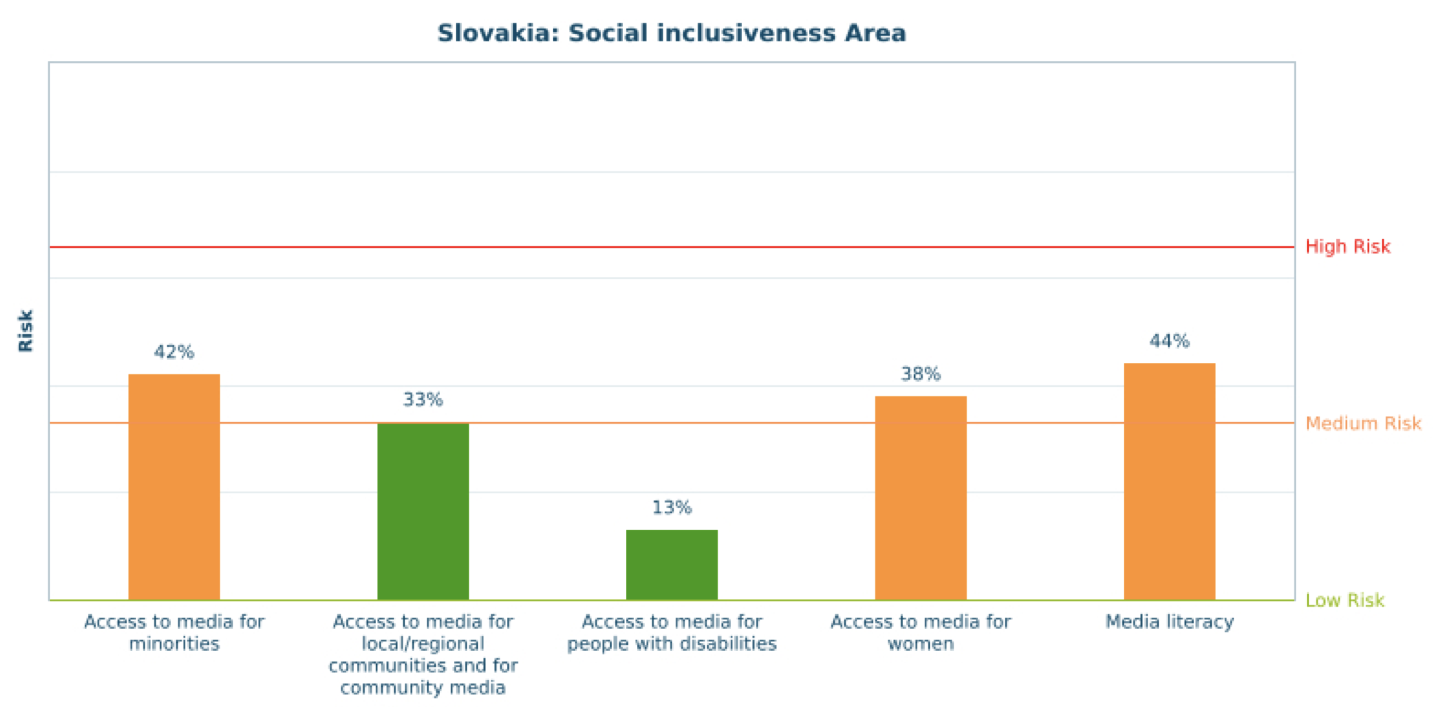

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (34% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator Access to media for minorities scores medium risk (42%). While access to media for minorities in respect of traditional national (national and religious) minorities is fairly well covered via mainly PSM broadcasting, regional and local radio and TV broadcasting as well as press media dedicated to these, both in PSM broadcasting and in press support schemes provided by Government, other groups are sometimes marginalized. Though there is not e.g. a separate TV service for national minorities, there is a regular broadcasting for these minorities. As for religious minorities PSM are: ‘providing space for the activities of registered churches and religious organizations in broadcasting’ (in Slovakia the church has to be registered by the Ministry of culture to receive public funding and receive additional benefits including act of marriage in front of the cleric to be recognized as a legal act). However, there is no clear method in allotting the space for representation in respect to access to airtime by different groups especially in the context of mentioned problematic formulation ‘registered churches and religious organizations’. The article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights does not impose governmental registration as precondition for freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

As a positive while there was recently increased effort in improving legislation regarding the hearing and sight impaired people. However, there is also PSM legal obligation in relation to serving ‘social’ minorities’, the problem is that there is neither definition nor clear representation of other ‘social’ minorities, nor definition what does the wording ‘social’ in this context refer to. This problem extents to some traditional minorities grouping, e.g. the gender and sexual minorities have no representation or access to airtime. If there is any representation it is on rare occasion during the new program, if something that is considered newsworthy happens, and even then, this presentation is very limited and more than often presented in context of “traditional values”.

The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scored low, near medium risk (33%). Both registering the print outlet or allocation of spectrum or retransmission does not present major obstacles. They are not done on discretionary basis and as for press (print outlets) this is considered as a formality mainly for statistics and business regulation purposes. However, authorities support to local/regional media through subsidies or other policy measures should be viewed with caution, especially if there are no political influence safeguards in place. As for community media the funding scheme for subsidies is managed mainly by the Ministry of culture.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scored low risk (13%), mainly because of the recent legislative changes put in place regarding access to media for people with disabilities and effort to speed up ongoing implementation. These measures include mainly obligations for broadcasters, and especially PSM. As an example; within the legal definition a multimodal approach to the programme service has to be broadcasted simultaneously with the main television broadcasting service, that is, certain amount of programs with subtitles or sign language for the hearing impaired persons, and audio description for the sight impaired has to be aired. This is paired with sanctions for non-implementation, and obligation for retransmission operators to provide devices that enable decoding of such programmes.

The indicator Access to media for women scored medium risk (38%). An Anti-Discrimination Law is in place and PSM have a policy on gender equality. However, there is lack of data on effectivity of implementation and gender statistics on representation of women, in general, if existent, are not generally accessible.

The indicator on Media literacy scored a medium risk (44%). The government policy introduced media literacy into school curricula as a compulsory cross-cutting subject at the level ISCED 3, and as a cross-cutting subject at the ISCED 2 level and the ISCED 1 level; that is; from elementary to upper secondary education. However, problem is with qualified educators and focus of the curricula. As the expert interviewed on the subject stated; there is a need for further education and training of teachers especially in the field of developing and encouraging critical opinion among students. This is particularly important in developing capability to form critical opinions based on various reliable sources, distinguish fake news online and understand limits of freedom of expression in regard to hate speech.

4. Conclusions

The conditions of media pluralism in Slovakia, as resulted from this Monitor, show both progress and continuous need for improvement.

Progress has been made mainly in protection of journalistic sources by application of good legal provisions, continuous usage of access to information as well as newly implemented legal provisions regarding access to media by people with disabilities. As always, the implementation and situation in practice of these need to be monitored regularly so not to relapse

As for media concentration, though legislation is set and monitored there is still not enough information publicly available, especially in regard to market shares. Nevertheless there is not one dominant player that would dominate market.

The major drawbacks are still limited political independence, that scored highest risk, of primarily local media that are being funded, and often indirectly owned by local governments and are exposed to political pressure. There should be some legislative safeguards allowing funding on transparent basis and at the same time limiting possibility of political influence. These could be combined with editorial independence safeguards.

In this regard, also editorial independence is lagging behind due to non-existent legal position of editor-in-chief and related safeguards. One of the possible solutions for this issue would be creating co-regulation model (Standards body) that would both create general ethical framework standards and oversee their implementation via deciding on complaints and dispute resolution on ethical issues.

Minorities, with the exception of traditional national and registered churches, such as gender and sexual minorities, do not have adequate access to media. There is obvious need to adopt legislative measures along with some subsidies schemes to overcome this drawback in minorities representation. This is necessary not only for the benefit of these minorities as such; but also for wider education purposes considering hate speech or ignorance of rights of these groups, that include not only gender and sexual minorities, but also new national or ethnic minorities as well as conservative views on role of women in the society in Slovakia. Regarding competences and expertise the Ministry of Justice might be a more suitable candidate for drafting framework measures than Ministry of Culture.

There are needs for additional safeguards in relation to PSM. Mainly in securing its funding that wouldn’t depend on political mood but set mechanism as to promote its independence. Also set of legal rules needs to be put in place regulating where and how these funds are used, so not to disturb the competition on the market where already PSM has an advantage; since it is not only a state supported media but also the only broadcaster that has a radio and television broadcasting service under one roof. These measures should be paired with promoting greater political independence of PSM, especially in naming and removing general director of PSM and chief editorial staff.

As for media literacy the situation is in general favourable in respect of measures adopted, nevertheless there is a need for further education and training of teachers especially in the field of developing and encouraging critical opinion among students. Moreover, media literacy measures should have a wider scope, encompassing not only students but also the broader population in order to improve knowledge on aspects such as expansive information barge of multiple information sources of various credibility and quality, critical approach to media and development of opinion based on knowledge as well as on multiple and reliable sources.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Željko | Sampor | PhD Candidate | Pan-European University | X |

| Kristina | Kročkova | PhD Student | Pan-European University | |

| Vladimir | Ruman | Lawyer (Advocate) |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Ľuboš | Kukliš | Director | Council for Broadcasting and Retransmission |

| Zuzana | Mistríková | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | |

| Tomáš | Kamenec | Lawyer | Press Council of The Slovak Republic |

| Radoslav | Kutaš | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Media Institute |

| Ivan | Antala | Vice president | Slovak Independent Broadcasters Association |

| Pavol | Múdry | Representative of a journalist organisation | Slovak Committee of The International Press Institute |

| Slavomíra | Salajová | Creative Industry Forum |

References

Velšic, Marian. Mladí ľudia v kyberpriestore – Šance a riziká pre demokraciu. Bratislava: Inštitút pre verejné otázky, 2016. ISBN: 978-80-89345-59-5

SITA, Internet ešte nikdy nepoužilo 14 % obyvateľov EÚ. 81 % domácností na Slovensku má prístup k internetu, 21.12.2016

Broadcasting Council Report 2015 SK -The Council for Broadcasting and Retransmission – 2015

KOMUNÁLNE VOĽBY 2014 – Financovanie kampane vo voľbách primátorov krajských miest SR (výskumná správa) – Inštitút pre verejné otázky -Grigorij Mesežnikov – Jaroslav Pilát – Peter Kunder – Ján Bartoš – 2015- Civil Society Report.

Media statistics -Ministry of Culture – 2016- Data and Statistics [https://www.mksr.sk/vdoc/424/vysledky-kult-2015-29c.html]

Mediálna výchova -National Institute for Education (Štátny pedagogický ústav) – 2016 [https://www.statpedu.sk/clanky/statny-vzdelavaci-program-svp-pre-gymnazia-prierezove-temy/medialna-vychova]

SSN -SSN – 2016 [https://www.ssn.sk/]

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/