Download the report in .pdf

English

Author: Beata Klimkiewicz

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF.

In Poland, the CMPF partnered with Beata Klimkiewicz, Institute of Journalism, Media and Social Communication at the Jagiellonian University, Kraków, who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

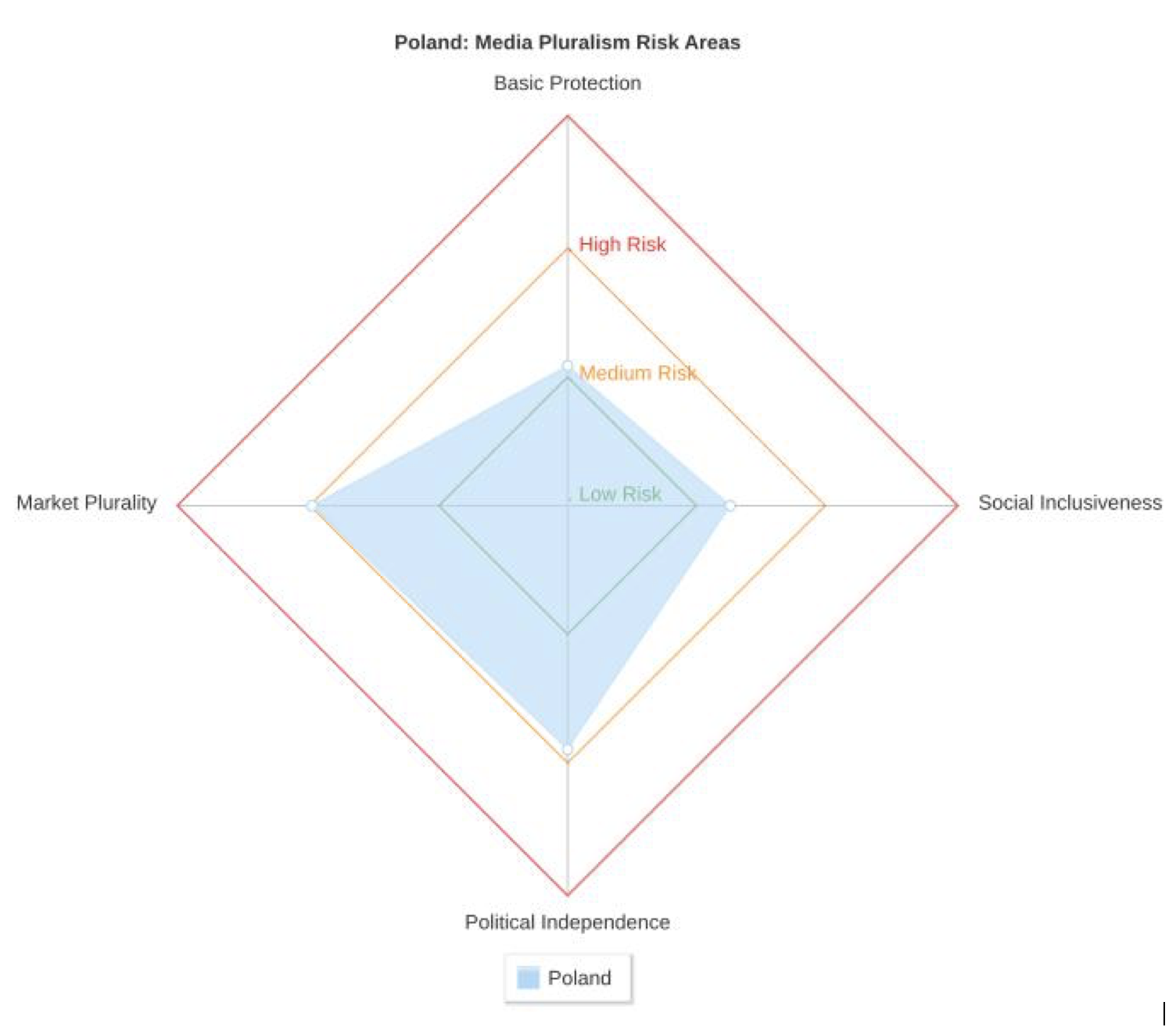

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Understanding current condition and risks to media pluralism in Poland requires a brief consideration of a social, economic and political context. With a population size of 38.427 million[2], Poland accounts for a relatively large media and linguistic market in Europe. . An ethnic and linguistic structure of the population is relatively homogenous with 97% of citizens identifying with a Polish nationality. The state officially recognises nine national minorities and four ethnic groups, and one language (Kashubian) enjoys officially the status of a minority and regional language.[3] According to the last 2011 census,[4] the largest minority group are Silesians (1.1%), which are not officially recognized as a national minority. Other declared minorities account below 1%. In these circumstances, the overwhelming amounts of media contents and services are produced in Polish, largely for the Polish audience.

A relatively stable economic situation and steady growth constitute a supportive environment for development of various media services, including new online media. Proportions of both, foreign and domestic capital and ownership (both EU and non-EU) in the media sector are quite significant. The Polish media environment is composed of strong and concentrated TV networks (including both private and public), which dominate news provision, declining, but still influential in opinion-formation, newspaper groups, and growing web portals.[5] A volatile and swiftly-changing political scene in Poland has stabilized since more than last 10 years. Left-oriented and social-democratic movements have lost their mass appeal, and the political spectrum is dominated by two actors – the Civic Platform (centre-right, liberal party) and Law and Justice (conservative right-wing party). The victory of Law and Justice Party in the parliamentary election in October 2015 was marked by a historical precedent. For the first time since 1989, the single party has formed a majority government, in addition supported by the President sharing the same political background. Media policy and regulatory changes introduced by the government and parliament were part of a set of 25 main reforms in various fields of social and economic life including family policy, public finance, national security, justice, media, under the formula of a “good change” (dobra zmiana). Media policy changes were based on the two broadcasting law amendments[6] affecting in principle appointment and operation of PSM and a leading national press agency (PAP), as well as competences of constitutionally recognized media authority – National Broadcasting Council (Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji – KRRiT). These regulatory developments sparked criticism of various international and national organisations, including CoE, OSCE, EBU. The European Commission took an unprecedented move to launch an investigation into the rule of law in Poland. Frans Timmermans, First Vice-President of the European Commission, addressing two Polish ministers (of Foreign Affairs and Justice), referred explicitly to freedom and pluralism of the media as one of the common values on which Union is founded, adding that “Protocol 29 to the Treaties equally recognizes that the system of public broadcasting in the Member States is directly related to the democratic, social and cultural needs of each society and to the need to preserve media pluralism.”[7] In 2016, press freedom in Poland was evaluated more critically by both Freedom House (Poland received the highest score since 2005 – 28) as well as Reporters Without Borders (Poland moved to the category of ‘fairly good’ press freedom, placing itself on the 47th position in the ranking, with score 23.89).

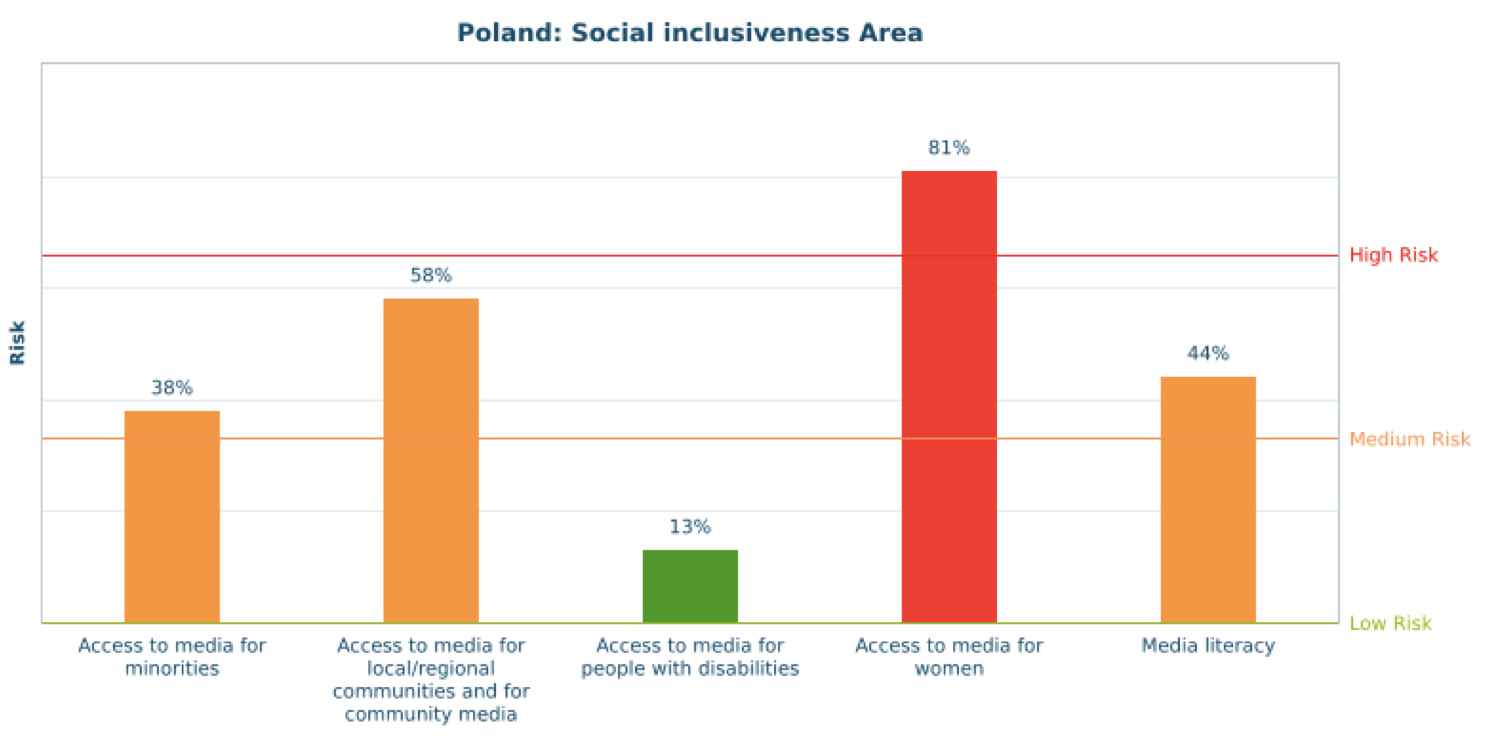

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The general conditions of media pluralism in Poland demonstrate a medium risk level in all measured areas.. The area of basic protection detects medium risk near low level, while the scores for market plurality and political independence reach the edge of the high risk level. Ownership media concentration (both horizontal and cross-media) present traditionally one of the largest threats to diversity in market plurality area, and these structural conditions have endured for a relatively long period of time in Poland. Another problematic issue includes independence of PSM governance and funding (83%), that reflects 2015 and 2016 regulatory changes resulting in control of PSM appointment procedures by the government first, and next by a newly created PSM regulatory body nominated by the parliamentary majority and president. This issue, among others (criminalization of defamation, surveillance, invigilation of journalists and 2016 amendment to the Police Act) contribute to medium risk near high level of the indicator measuring freedom of expression within the basic protection area (58%). Access to media for women presents the highest risk (81%) in the social inclusiveness area. Although women contribute to a significant portion of Polish journalists, they are underrepresented in PSM boards. They are also not protected by equality law measures that would specifically apply to employment of women in media organisations or offer comprehensive gender policy in PSM.

Low risk indicators include protection of right to information (25%) and independence and effectiveness of the media authority (6%) within the basic protection area, and access to media for people with disabilities (13%) within the social inclusiveness area. Although variable measuring journalistic protection, standards and protection scores relatively low (25%), working conditions of journalists in Poland do not provide sufficient social protection. Journalistic organisations seem to be so divided in their membership, goals and values that there is a lack of a common vision that could be successfully articulated to media industry stakeholders.

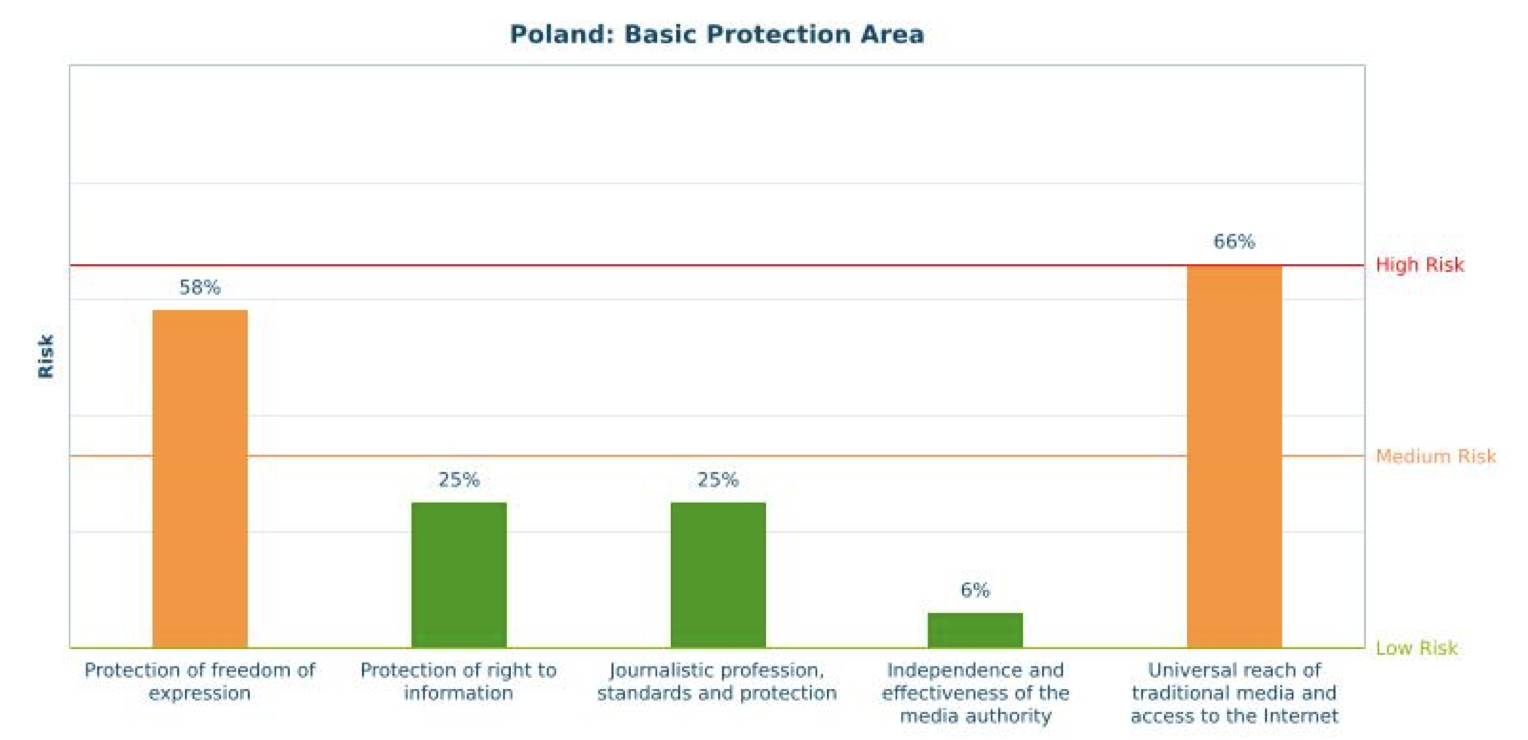

3.1 Basic protection (36% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The basic protection domain manifests medium risk for pluralism in Poland. Although freedom of expression is generally respected in Poland, and legal measures, including the Constitution, provide sufficient protection, several limitations can be observed. First of all, the problem of political influence over the governance of PSM, discussed below under the section on political independence, generally affects freedom of expression in practice, mainly with regard to self-censorhip of journalists. Second, the state has not decriminalised defamation. . The repeal of Article 212 from the Penal Code has been requested by various organisations representing journalists, media and civil society in 2011,[8] and then again in 2014, and most recently in September 2016 with the leading role of the Commissioner for Human Rights. The initiative was rejected in March 2017 by the Senate Committee for Human Rights, Rule of Law and Petitions. Third, the problem of surveillance, and use of digital data by the police and secret services poses questions about uncontrolled access to personal data after the 2016 amendment to the Police Act.[9] On the other hand, protection of right to information, journalistic profession and independence, as well as effectiveness of the media authority seem to indicate low risk.

The indicator on Protection of freedom of expression scored medium risk (58%). Freedom of expression is generally respected in Poland, and is protected under the Polish Constitution (1997) in the Article 54 and Article 14 (freedom of the press and the media).[10] According to international organisations measuring freedom of the press (Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders), Poland belongs to countries with ‘free’ press and ‘fairly good’ condition of the press, although in comparison with previous years, the 2016 evaluation articulates visible criticism, mainly due to the noticed influence of the government over the appointment of PSM boards in 2016. Second is the concern over criminalized defamation. A relatively formalistic treatment of some defamation cases by the domestic courts leads repeatedly to applications submitted to the ECHR, judging time and again a violation of Article 10 of the Convention (e.g. Applications no. 19127/06; 48723/07; 34447/05). The OSCE in its final report summarising observations from the parliamentary elections 2015 recommends that “consideration should be given to removing provisions that foresee criminal liability for defamation and public insult” in order to effectively ensure media freedom and protect freedom of speech, especially during an election period.[11] Third is the problem of a growing possibility of surveillance, and enhanced use of personal (including journalists’) data by the police and secret services.

The indicator on the Protection of right to information shows a low risk level (25%). The right to information is legally protected and generally respected in Poland. In practice, the smooth implementation is affected by limits of a relatively narrow definition of public information and delays in timely responses to information requests.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection also present a low risk level (25%). In general, access to the journalistic profession is unrestricted in Poland and very rarely some attacks or threats to the physical safety happen[12]. Working conditions of journalists are marked by economic pressures and employment instability. Journalistic organisations seem to be too fragmented to effectively represent the professional journalistic environment vis-à-vis other stakeholders.

The Independence and effectiveness of the media authority reach a very low risk level (6%). The National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT – established in 1993) has been constitutionally recognised as one of the organs of state control and protection of rights. Its role is specified under Article 213 as safeguarding the freedom of speech, the right to information as well as safeguarding the public interest regarding radio broadcasting and television.[13] Although formal procedures of KRRiT’s appointment and accountability respect balance of political powers and protect against conflict of interests, in practice KRRiT has been exposed to repeating and constant political pressures. A current establishment of a new body for “National Media” (RMN) weakens the constitutional competences of KRRiT, especially in the area of PSM appointments. A composition of RMN strongly reflects influence of political parties and does not limit a possible membership by active politicians and the Members of Parliament. Yet as the body does not replace KRRiT in media regulation generally, it has not been a subject of analysis in the case of this indicator.

In terms of the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet, the indicator scores medium risk (66%), very close to the high risk threshold. Universal coverage of traditional media, in particular radio, has been lower in Poland than in some other countries of the EU. Combined with the access to the internet, this variable amounts to the high edge of the medium risk.

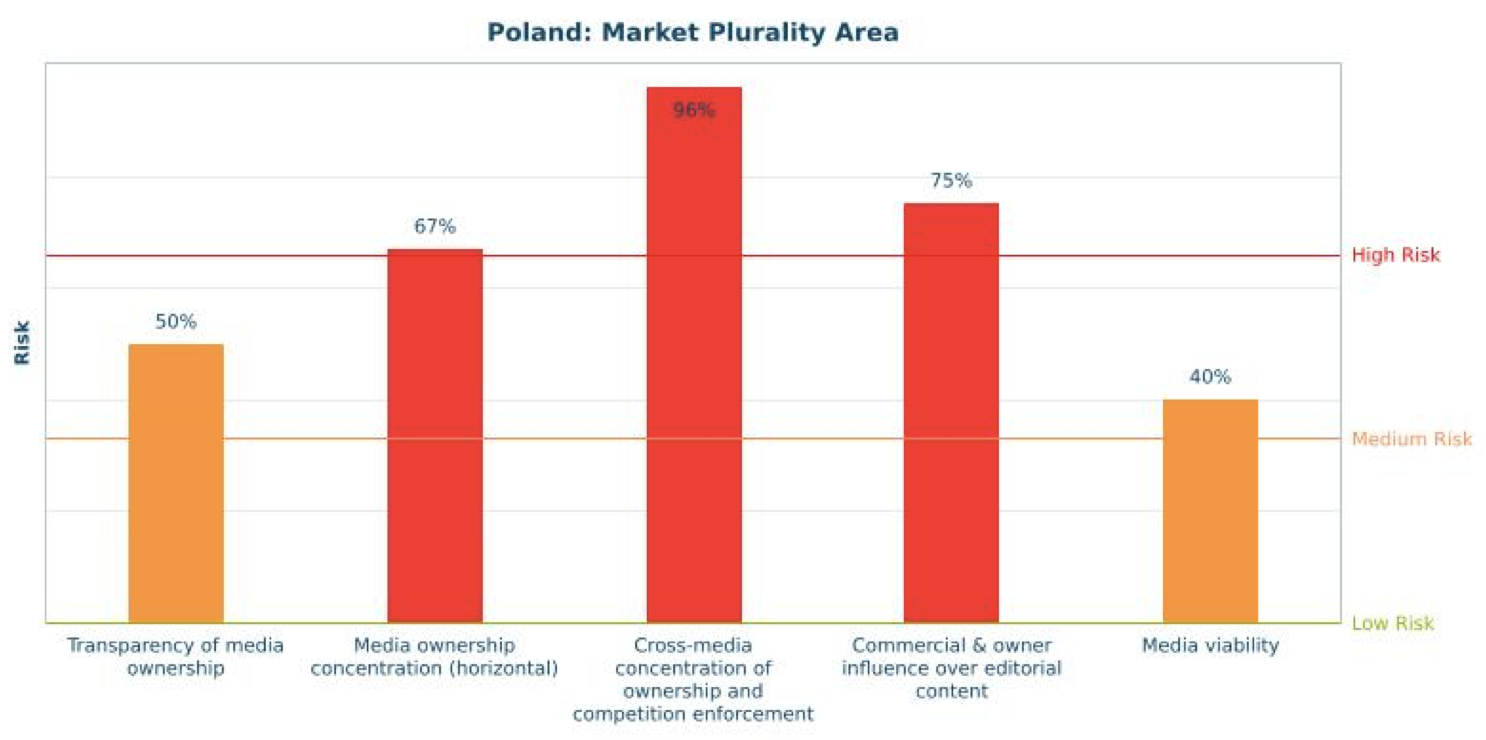

3.2 Market plurality (66% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The market plurality domain demonstrates a medium near high risk. k. Key problems in this area revolve around a high level of concentration on both horizontal and cross-media markets, as well as a lack of specific rules that could, on the one hand, foster more competition and on the other hand, prevent a high degree of cross-ownership. Legally-grounded as well as self-regulatory mechanisms providing protection of journalists and editorial content against commercial and owner influence are, with some exceptions, missing in Poland. Although transparency of media ownership is guaranteed for the state agencies, the general public does not enjoy free and full access to the data about ownership and financial conditions of the media. The picture of media viability seems mixed, combining both evidence for growth in certain media sectors (audiovisual, radio, online advertising) as well as decline (print media).

The indicator Transparency of media ownership scored medium risk (50%). Whereas there are several obligations in company and broadcasting laws that require disclosure of certain data about media ownership in Poland,[14] the public does not enjoy free and full access to the data about ownership and financial operations of the media. Most data are collected by public agencies (such as KRRiT and UKE), while media users have very limited knowledge about media ownership and media financing structures.[15]

The indicator Media ownership concentration (horizontal) scored a high risk (67% risk). Both competition and broadcasting laws tackle some forms of horizontal media concentration. However, the 2007 Act on Competition and Consumer Protection does not specifically recognize the media sector.[16] The concentration in revenue and audience markets are rather high in Poland. In 2014, the top 4 audiovisual owners altogether achieved 93% and in 2013, 95% shares in the revenue market, while the top 4 radio owners 90% in 2014 and in 2013, 78%. Likewise in the audience markets, the share of the top 4 audiovisual owners stood for 70.2% in 2015 and share of the top 4 radio owners for 82.2%.[17] The share of the four leading press groups in the overall circulation of the press market reached around 70% in 2013, 77.5% in 2014 and 76% in 2015.[18]

Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement acquired 96% of risk, which is a very high risk. Current media and competition laws do not contain specific rules that could foster more competition and at the same time prevent a high degree of cross-ownership between the different media sectors. The overall score for this indicator proves to be the highest among all of the indicators concerning Poland.

The indicator on Commercial and owner influence over editorial content also scored a high risk (75%). Legal and self-regulatory protection against commercial and owner’s influence over staff appointments and dismissals are missing in Poland. Although there are some provisions protecting against advertorials, their effective implementation in practice is problematic as it requires proof of acting of a journalist “for his/her own financial or personal benefit”.[19] In general, an empirical evidence proving commercial influence over editorial content is scarce in Poland, but journalists signal several problems such as advertisers’ preference of light-type genres at the expense of serious investigative journalism.

Media viability scored a medium risk (40%), the lowest for Poland in the media plurality area.The picture of media viability seems rather mixed. On the one hand, revenues in some media sectors (audiovisual and radio) increased over the past two years, and Poland is ranked quite high in terms of paying for digital news.[20] On the other hand, the revenues in the newspaper industry have decreased, and media have not enjoyed any direct support, with the exception of tax reduction and a small number of direct state subsidies. The 2004 Act on Commodity and Service Tax sets the lowered tax level – 7% for the press in a printed form and press that is distributed on CDs, records and other channels. This however does not include digital content. The Act sets 5% of the tax level for the printed books and books that are distributed on CDs, records and other channels, as well as for specialised periodicals[21].

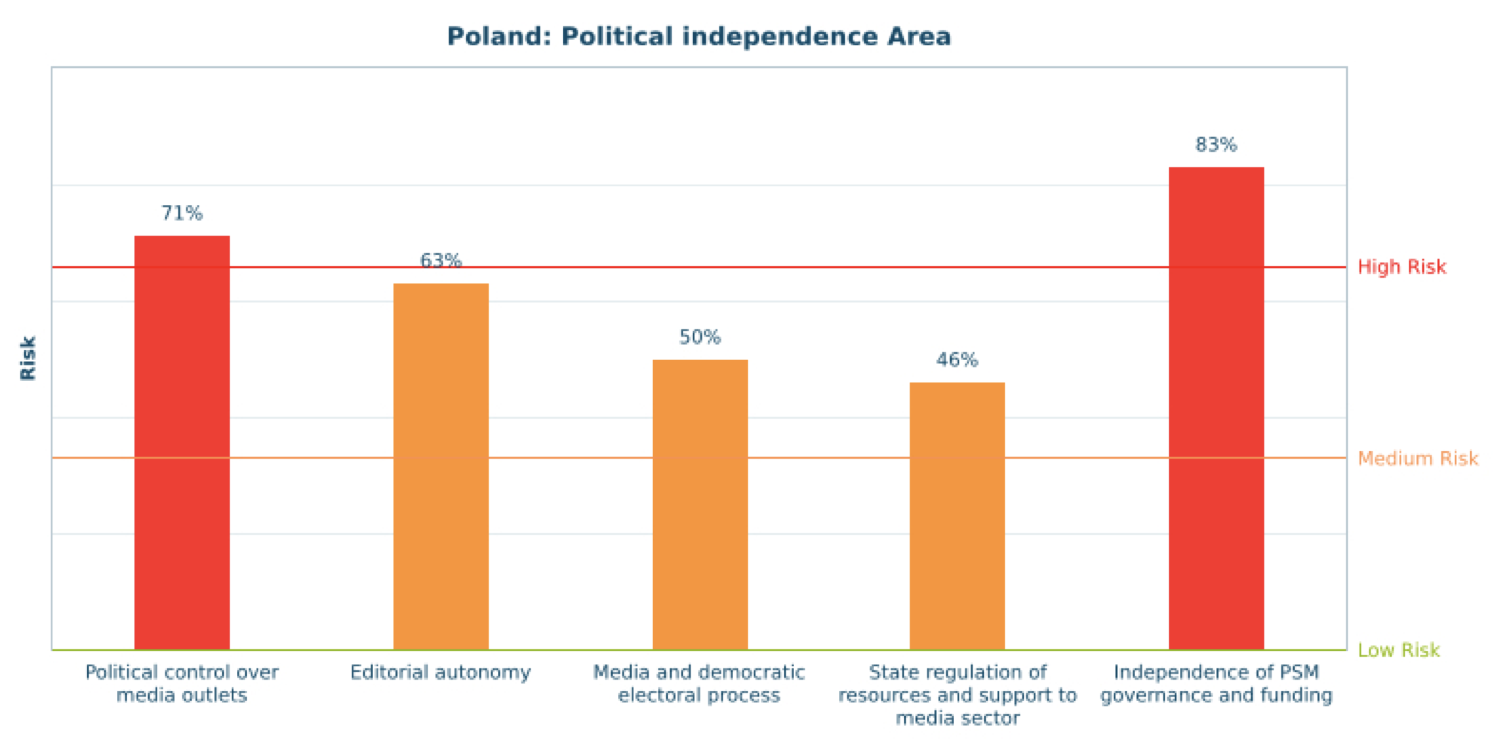

3.3 Political independence (63% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

In the area of political independence, the highest risks account for: political control over media outlets manifested particularly in a lack of measures protecting against direct and indirect control of media by politicians, and weak independence of PSM. At the end of 2015 and 2016, PSM appointment procedures underwent significant legal changes in Poland, resulting in replacement of boards and directors in place with the new staff appointed by the Minister of Treasury. In consequence, Telewizja Polska (TVP) and Polskie Radio (PR) witnessed massive layoffs of numbers of journalists, some after 20 years of work in the public service. Later in 2016, new regulatory body for “National Media” was established (Rada Mediów Narodowych – RMN). Political pressure over PSM is not a new phenomenon in Poland, yet direct involvement of the government in the PSM appointment and weakening competences of National Broadcasting Council present a deepening of this problem. Other three indicators in this domain score for the medium risk. Among these, a lack of transparency and free access to data about state advertising, should be addressed.

Political control over media outlets scores a high risk (71%). In general, legal regulations addressing conflict of interests between media owners and political parties or politicians, as well as rules protecting against direct and indirect control of media by politicians, are missing in Poland. While the largest audiovisual or radio networks have no direct affiliations with political parties, the problem of political parallelism persists in Poland, and is reflected in politically partisan journalistic culture as well as clear political orientation of a large number of media outlets.

Editorial autonomy (63% – medium risk), especially as regards appointments and dismissals, is not subject to legal regulatory safeguards in Poland. Editorial independence is addressed by several self-regulatory measures, but due to the high fragmentation among journalistic organisations, these are hardly effective.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a medium risk (50%). During election campaigns, access to airtime on PSM channels and services is guaranteed for political actors both under the media and electoral laws in Poland.[22] Yet, available monitoring of media content suggests that both PSM and commercial channels tend to devote more time and representation to large political parties, in particular to PO (The Civic Platform Party) and PIS (The Law and Justice Party) than the other parties in the campaigns.[23] The monitoring of 2014 local elections campaign showed a thematic shift toward tabloidization – many aspects of news reporting seemed to focus on curiosities, rather than essentials. Another aspect detected by the monitoring of the 2015 parliamentary elections pointed to dichotomizing and polarising of the political debate.[24].

State regulation of resources and support to the media sector also scores a medium risk (46%). As regards licence-granting policies for broadcasting, the legislation provides fair and transparent rules on spectrum allocation. In general, the State does not use a direct subsidy scheme for the media with a small exception of minority press and specialized periodicals. Indirect subsidies (tax reduction for newspapers) are distributed proportionally in this segment. Yet by contrast, state advertising to media outlets is not monitored and lacks transparency, especially vis-à-vis the general public.

Independence of PSM scored the highest risk (83%) in the political independence domain. At the end of 2015 and 2016, PSM appointment procedures underwent significant legal changes in Poland. At the first stage, 2015 “Small Media Act” allowed Minister of Treasury to appoint new PSM boards, at the second stage a new regulatory body for PSM (redefined in the law as “National Media – NM”) was created. This body – the National Media Council – has weakened regulatory competences of the National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT) in the area of PSM appointment[25] In the opinion of Polish Human Rights Defender, the Act violated constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and media freedom by subordinating PSM directly to the government and restricting the constitutional role of the National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT)[26]. This opinion was partly backed on 13 December 2016 by the Constitutional Tribunal (gathered in a smaller group of five judges) in which it held certain provisions of the legislation unconstitutional.[27]

3.4 Social inclusiveness (47% risk medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The social inclusiveness area generally scores medium risk. This domain seems more diversified than areas previous analysed, containing both an indicator with a very small risk (e.g. access to media for people with disabilities – 13% ) as well as a high risk (access to media for women – 81%).

The indicator Access to media for minorities scores medium risk (38%), which reflects the existence of legal guarantees on one side, but insufficient proportion of programming in practice. Access to airtime on PSM to minorities is guaranteed in Poland by both media and minority laws.[28] Yet, the portion of programming available via channels of both PSM and minority media does not seem to be proportional to the size of the minority population.

The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and community media accounts for the medium risk (58%).PSM – Polish Radio in particular – provide a variety of regional channels and coverage of local and regional issues.Yet other local and regional media, some of which undergo difficult situation, are not supported systematically from subsidy mechanisms. Community media in Poland are legally recognised as ‘social broadcasters’ under the 1992 Broadcasting Act. The law postulates a possibility of awarding licences for ‘social broadcasters’ under special conditions (free of charge), but does not ensure independence of community media.[29] In practice, their function and autonomy is relatively limited.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scores low risk(13%). The policy concerning access to media content by the physically challenged people has improved in recent years. On the one hand, it consists of legal requirements aiming at gradually ensuring the availability of programmes provided for disabled persons[30]. On the other hand, the National Broadcasting Council regularly monitors fulfillment of these obligations by broadcasters and providers of on-demand audiovisual media services.

The indicator Access to media for women scores high risk (81%).In Poland, there are no specific legal measures that would refer to employment of women in media organizations, but general provisions apply that protect equal rights of women and men in employment, including constitutional provisions and the Labour Code.[31] PSM have no comprehensive gender equality policy and the representation of women on PSM management boards is scarce.

The indicator Media literacy scores medium risk (44%) ‘Media literacy’ or ‘media education’ is recognized as one of the leading tasks of both KRRiT and PSM (Articles 6.2; 21.1a).[32] Recently, KRRiT has been involved more actively in initiating various activities promoting media literacy[33] and ‘informal’ media literacy activities have been growing. At the same time, formal development of relevant curriculum at a school level is largely missing and digital competencies measured among the population reveal gaps and divides.

4. Conclusions

Given the complexity of media pluralism assessment within all its four domains, Poland performs as a medium-risk country.

Basic protection domain

While freedom of expression is generally respected in Poland, some indicators in this domain detect a medium risk. To balance this risk, it would be useful to:

- address criminalisation of defamation and ensure that the Penal Code (Article 212 in particular) is not used in unduly restrictive way to silence journalistic criticism of public figures,

- strengthen an autonomy of National Broadcasting Council with leadership (reflecting not only political structure of the parliament and president, but representing a social and cultural milieu including NGOs, educational institutions, journalistic associations and others) committed to operating transparently and for the public benefit.

Market plurality domain

Market plurality accounts for the highest risk score among all domains. This has mainly been caused by a relatively high level of media concentration, that has endured as a long-term issue characterising Polish media landscape in various media sectors, but also across them. In this context, it would be worthwhile to:

- address cross-media ownership, at least in media regulation and establish competition policy regimes that would be more sensitive to specific features of relevant media markets,

- design and implement media transparency through establishing a media register offering free-of-charge and full public access to information about: the ultimate owner, the official location of the company’s seat, information where the company pays taxes, a full catalogue of owned media services and outlets, including social media, online portals, outdoor advertising, etc., total revenues, advertising revenues, with detailed information on proportion of revenues collected from state or public advertising.

Political independence domain

The highest risk in the political independence domain stands for the indicator measuring independence of PSM. Also, political control over the media outlets reveals a relatively high risk. In terms of policy suggestions, this domain would benefit in particular from:

- ensuring impartial model of PSM governance, especially appointment procedures that would allow to select PSM boards without influence of the government and commercial interests,

- providing substantial and long term funding for PSM,

- introducing disclosure of data on state advertising and providing a transparent scheme of its distribution across particular media outlets.

Social inclusiveness domain

Social inclusiveness presents one of the most diversified among all of the domains, with both high and low risk indicators. An inclusive access to media by various social groups in society might improve with:

- applying a wider policy approach to the entire media system, and not relying simply on tasks of PSM to cater for local or minority communities, or on municipal support that is often bound by high political dependency on local politics,

- legal and policy recognition of community media while respecting their independent status and offering some mechanism of support,

- legal and policy recognition of gender equality, particularly in PSM.

To summarise, fostering media pluralism requires a more holistic policy approach towards development of a Polish media and communication environment, which should offer balancing and complementing of various media functions (such as public service, commercial, community-related, etc), and at the same time, empower media users with equal access, media transparency and literacy.

Annex 1. Country Team

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Beata | Klimkiewicz | Associate Professor | Institute of Journalism, Media and Social Communication, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland | x |

Annex 2. Group of Experts

Any country-specific deviation from the standard Group of Experts procedure should be briefly explained here.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Maria | Borkowska | Senior Analyst | National Broadcasting Council |

| Alicja | Jaskiernia | Professor | University of Warsaw |

| Jędrzej | Skrzypczak | Professor | Adam Mickiewicz University of Poznań |

| Maciej | Hoffman | Director General | Press Publishers’ Chamber |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] GUS (Central Statistical Office) (2016) Area and Population in the Territorial Profile in 2016 (available at: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2016-r-,7,13.html; retrieved 20.10.2016).

[3] The 2005 Act on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages (Ustawa o mniejszościach narodowych i etnicznych oraz o języku regionalnym), adopted on 6 January 2005, Official Journal 2005, No 17, item 141. (available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20050170141; retrieved 20.10.2016).

[4] GUS (Central Statistical Office) (2011) Raport z wyników: Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 (The Concluding Report: 2011 Census) (available at: https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/lud_raport_z_wynikow_NSP2011.pdf; retrieved 20.07.2016).

[5] Indicator (2015) Różnorodność treści informacyjnych w Polsce z perspektywy użytkownika (News diversity from a user’s perspective in Poland) (available at: https://www.krrit.gov.pl/krrit/aktualnosci/news,2185,pluralizm-polskich-mediow-z-perspektywy-odbiorcow.html; retrieved 20.07.2016).

[6] Act Changing the Broadcasting Act, so called “Small Media Act” (Ustawa o zmianie ustawy o radiofonii i telewizji, tzw. “Mała Ustawa Medialna”) adopted on 30 December 2015, Official Journal 2016, item 25. https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20160000025, unofficial translation: https://www.krrit.gov.pl/en/for-broadcasters-and-operators/legal-regulations/.

Act on the National Media Council Ustawa o Radzie Mediów Narodowych) adopted on 22 June 2016, Official Journal 29 June 2016, item 929, https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/du/2016/929/1.

[7] The letter of Frans Timmermans to the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Justice, 30 December 2015, (https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:RiR3IB_n4aIJ:g8fip1kplyr33r3krz5b97d1.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Letter-Timmermans-Poland.pdf+&cd=3&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl&client=firefox-b; retrieved 19 January 2017).

[8] Under the campaign “Withdraw the Article 212”, https://pl-pl.facebook.com/wykresl212.

[9] The Act Changing the Police Act and some other Acts (Ustawa o zmianie ustawy o Policji oraz niektórych innych ustaw) adopted on 15 January 2016, Official Journal 2016, item 147. (available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20160000147).

[10] The Constitution of the Republic of Poland (Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) adopted on 2 April, 1997, Official Journal, 1997, No 78, item 483. (available at: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/angielski/kon1.htm; retrieved 20.09.2016).

[11] OSCE (2016) Republic of Poland: Parliamentary Elections, 25 October 2016, OSCE/ODHIR Election Assessment Mission Report, https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/poland/191566, p. 19.

[13] The Constitution of the Republic of Poland (Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) adopted on 2 April, 1997, Official Journal, 1997, No 78, item 483. (available at: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/angielski/kon1.htm; retrieved 20.09.2016).

[14] 2000 Code of commercial partnership and companies (Kodeks spółek handlowych) adopted on 15 September 2000, Official Journal 2000, No 94, item 1037; 1997 Act on National Court Register (Ustawa o Krajowym Rejestrze Sądowym) adopted on 20 August 2007, Official Journal 1997, No 121 item 769; 1992 Broadcasting Act…

[15] Indicator (2015) Różnorodność treści informacyjnych w Polsce z perspektywy użytkownika (News diversity from a user’s perspective in Poland) (available at: https://www.krrit.gov.pl/krrit/aktualnosci/news,2185,pluralizm-polskich-mediow-z-perspektywy-odbiorcow.html.

[16] 2007 Act on Competition and Consumer Protection (Ustawa o Ochronie Konkurencji i Konsumentów) adopted on 16 February 2007, Official Journal, 2007 No 50, item 331, as amended (available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20070500331; retrieved 15.10. 2016).

[17] KRRiT (2016) Informacja o podstawowych problemach radiofonii i telewizji w 2015 roku (Information about basic issues concerning radio and television in 2015) https://www.krrit.gov.pl/Data/Files/_public/Portals/0/komunikaty/spr-info-krrit-2015/informacja-o-podstawowych-problemach-radiofonii-i-telewizji-w-2015-roku.pdf

[18] Izba Wydawców Prasy (Chamber of Press Publishers) Lista tytułów (The List of Press Titles) (available at: https://www.iwp.pl/lista_tytulow.php?menu=2&IWP_wydawnictwaPage=9; retrieved 15 January 2017).

[19] Article 12.2; 1984 Press Law Act The Press Law Act (Ustawa Prawo Prasowe) adopted on 26 January, 1984, Official Journal 1984 No 5, item 24, as amended. (available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU19840050024; retrieved 10 September 2016 )

[20] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (2016) Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016, https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/; retrieved 10 September 2016 ).

[21] 2004 Act on Commodity and Service Tax (Ustawa o podatku od towarów i usług), adopted on 11 March 2004, Official Journal 2004, No. 54, item 535, as amended.

https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20040540535; retrieved 20.04.2017.

[22] 2011 Election Code (Ustawa Kodeks Wyborczy) adopted on 5 January 2011, Official Journal 2011, No 21 item 112 (Articles 116 – 122). 1992 Broadcasting Act (Ustawa o Radiofonii i Telewizji) adopted on 29 December 1992, as amended, Official Journal 1993, No 7, item 34 (Article 24.1).

[23] See e.g. KRRiT (2016) Monitoring kampanii wyborczych (Monitoring of electoral campaigns) https://www.krrit.gov.pl/dla-nadawcow-i-operatorow/kontrola-nadawcow/kampanie-wyborcze/

[24] KRRiT (2015) Monitoring kampanii wyborczych (Monitoring of electoral campaigns) https://www.krrit.gov.pl/dla-nadawcow-i-operatorow/kontrola-nadawcow/kampanie-wyborcze/

KRRiT (2015) Kto bezstronny, kto pluralistyczny? Monitoring wyborów parlamentarnych 2015 (Who is impartial? Whom pluralistic? The monitoring of parliamentary elections)

https://www.krrit.gov.pl/krrit/aktualnosci/news,2176,kto-bezstronny-kto-pluralistyczny-monitoring-wyborow-parlamentarnych-2015.html, retrieved 10.11.2016.

[25] Act Changing the Broadcasting Act, so called “Small Media Act” (Ustawa o zmianie ustawy o radiofonii i telewizji, tzw. “Mała Ustawa Medialna”) adopted on 30 December 2015, Official Journal 2016, item 25. https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20160000025, unofficial translation: https://www.krrit.gov.pl/en/for-broadcasters-and-operators/legal-regulations/

Act on the National Media Council Ustawa o Radzie Mediów Narodowych) adopted on 22 June 2016, Official Journal 29 June 2016, item 929, https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/du/2016/929/1

[26] Human Rights Defender (2016) Commissioner for Human Rights Appeal to the Constitutional Tribunal on media Law, https://www.rpo.gov.pl/en/content/commissioner-human-rights-appeal-constitutional-tribunal-media-law

[27] The Constitutional Tribunal judgement No K13/16, on 13 December 2016.

[28] The 2005 Act on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages (Ustawa o mniejszościach narodowych i etnicznych oraz o języku regionalnym), adopted on 6 January 2005, Official Journal 2005, No 17, item 141. (available at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU20050170141; retrieved 20.07.2016).

(Article 8.2. and Article 18); 1992 Broadcasting Act (Ustawa o Radiofonii i Telewizji) adopted on 29 December 1992, as amended, Official Journal 1993, No 7, item 34 (Article 21.1a.8a)

[29] Ibidem.

[30] 1992 Broadcasting Act (Ustawa o Radiofonii i Telewizji) adopted on 29 December 1992, as amended, Official Journal 1993, No 7, item 34, Articles 18a and 47g.

[31] The Constitution of the Republic of Poland (Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) adopted on 2 April, 1997, Official Journal, 1997, No 78, item 483. (available at: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/angielski/kon1.htm; ) – Article 33; 1974 The Labour Code Act (Ustawa Kodeks Pracy) adopted on 26 June 1974 , Official Journal 1974, No 24, item 141, https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU19740240141 – Article 11; 2010 Act on the implementation of some regulations of European Union regarding equal treatment (Ustawa z dnia 3 grudnia 2010 r. o wdrożeniu niektórych przepisów Unii Europejskiej w zakresie równego traktowania) adopted on 3rd December 2010, Official Journal of 2010, No 254, item 1700, https://www.rpo.gov.pl/en/content/act-3rd-december-2010-implementation-some-regulations-european-union-regarding-equal

[32] 1992 Broadcasting Act (Ustawa o Radiofonii i Telewizji) adopted on 29 December 1992, as amended, Official Journal 1993, No 7, item 34, Articles 6.2.13; 21.1a.11.

[33] KRRiT (2016) Media Road-Sign, https://www.krrit.gov.pl/drogowskaz-medialny/