Download the report in .pdf

English – Montenegrin

Author: Dragoljub Vuković

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF partners with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Montenegro, the CMPF cooperated with a team of experts led by Dragoljub Vuković, who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Montenegrin team organized a stakeholder meeting, on 9 december 2016, in Podgorica. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

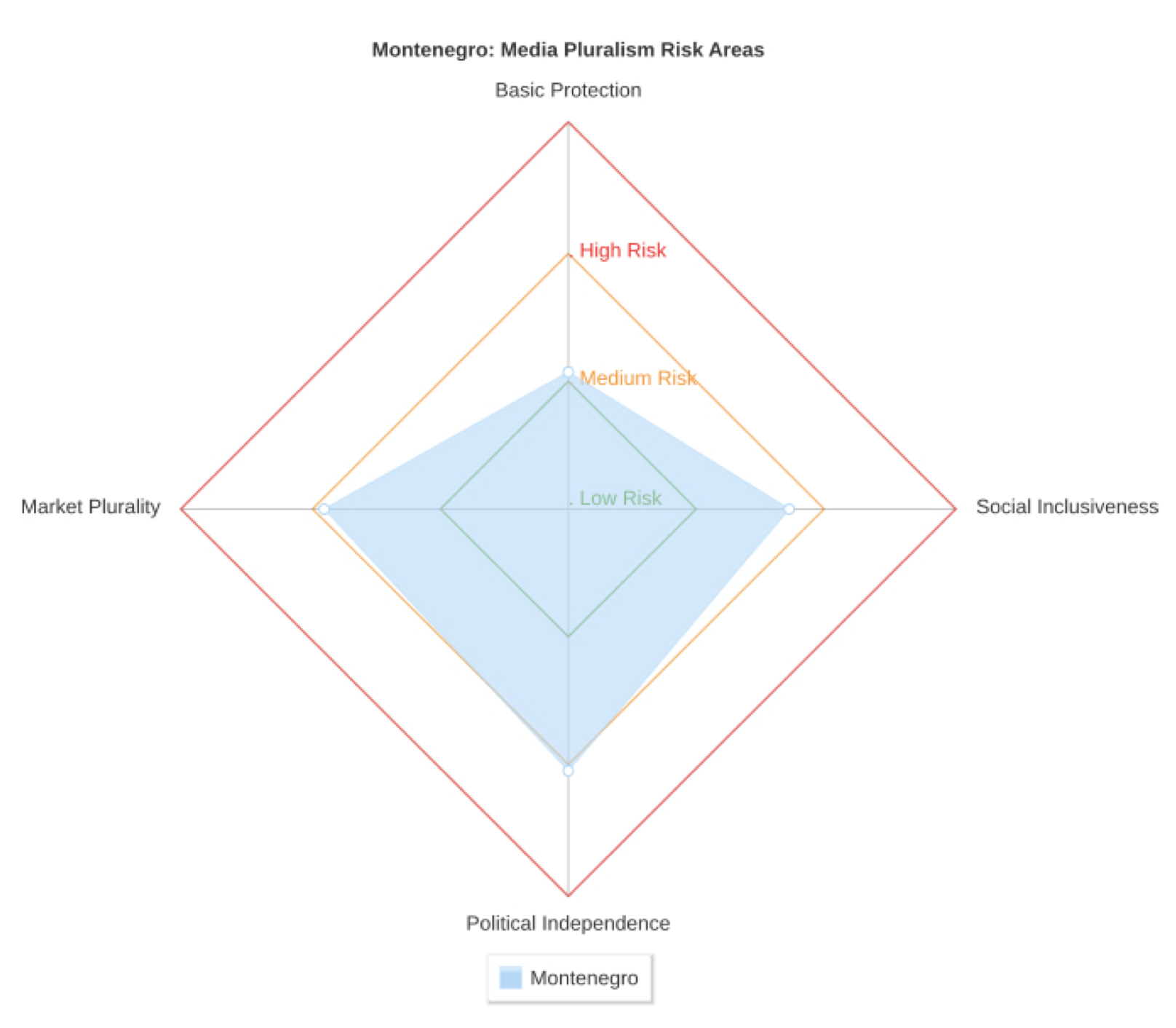

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic domains, which are considered to capture the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0 to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Montenegro is a Balkan country with 620,000 inhabitants that covers the area of 13,812 square kilometres bordered by the Adriatic Sea to the south-west, Croatia to the west, Bosnia and Herzegovina to the northwest, Serbia to the northeast, Kosovo[2] to the east and Albania to the south-east.

Montenegro is a multi-national and multi-religious community. According to 2011 census, 44.98% of the population define themselves as Montenegrins, 28.73% Serbs, 8.65% Bosniaks, 4.91% Albanians, 3.31% Muslims, 1.01% Roma, and 0.97% Croats. According to the Constitution, the official language is Montenegrin, but Serbian, Bosniak, Albanian and Croatian are also in the official use.

Montenegro’s economy is still in transition to a market economy with the ongoing process of structural reforms and privatisation of state-owned enterprises and resources. Dominant sectors are tourism and trade, while industrial production is limited mainly to electricity generation, steel, aluminium, coal mining and forestry. It relies heavily on capital inflows from abroad to stimulate growth. In 2015, the economy grew at the rate of 3.4% of GDP. The economy is still characterised by a large foreign trade deficit, high tax debt of companies, general illiquidity, high unemployment (18,15 %) and high public debt. At the end of 2015, public debt amounted to 2.3 billion euros or 65.69 % of GDP. The country does not have its own currency and uses Euro as legal tender.

Politics of Montenegro takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic and of a multi-party system. Although in 2015 there were 45 registered political parties in Montenegro, the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) is in power since the introduction of multiparty democracy in 1990. Its political orientation moved from the leftist party to supporter of neoliberal economic concept, and integration of the country in the EU and NATO. The current leader of DPS, Milo Djukanovic, with brief interruptions, was prime minister or president of Montenegro from 1991.

The Montenegrin media market offers plurality of views with five national and ten local TV stations, more than 40 radio stations, five dailies, and four significant news portals. The market worth in 2015 stood at around 36 million euros of total generated revenues. A significant part of the market belongs to public service broadcasters, with two national channels and three local ones, and 14 local public radio broadcasters. Mostly financed from the public budget, they make up over 60% of the audiovisual market. Openness of the market for strong regional media players intensifies competition and aggravates the economic viability of local media. TV remains the most dominant source of news, and the news portals have taken the primacy of the newspapers. Around 85% of the population uses the services of one of the commercial cable platforms for distribution of radio and TV programs.

In terms of editorial policy, the media scene is deeply divided along political lines between pro-government oriented media and their opponents. Regulatory bodies function independently from the government, but their financial independence is jeopardised by the Parliament which is responsible for the adoption of financial plans and reports of the Agency, and practices its right to modify them. Self-regulation is weak, and professional organizations, including Unions, do not have any significant influence.

Although the media legislation is largely aligned with international standards, initiatives for regulatory updates are in course, aimed to tackle challenging issues of overdependence of the national public service broadcaster to state financing, non-regulated area of state aid to media, protection of journalists, ownership concentration and market competition.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

As a candidate country for EU accession, Montenegro has largely aligned its media legislation with international standards. Privatization of once state owned media was completed in 2014 and a pluralistic market established long before. Defamation was decriminalized, and independent regulatory bodies established. As regards the basic protection indicators, key problems remain the silence of administration regarding the obligations on free access to information, and slow and inefficient court procedures in cases of defamation. A specific problem is the unresolved cases of attacks on journalists and media property, which coupled with poor social protection, and weak professional solidarity among the media professionals, creates unfavourable working conditions in the media.

Market viability and competition are still fragile. Public service media almost entirely rely on direct state support, which represents major part of the audiovisual market. Openness of the market and similarity of languages facilitates a dominant local prominence for big regional media companies, operated from Serbia, and belonging to Serbian and Greek owners, which makes local media difficult to sustain. Ownership concentration exists in the market, and state aid to the media sector is neither regulated nor transparent.

Political influence on editorial content is evident, yet the level is hard to determine, since there are no regulatory mechanism or practices to monitor or prevent indirect political interference with the media work. Basic data, such as audience share or marketing revenue are not publicly available.

Regional and local communities have access to media mainly through the network of public service media financed by local authorities. When it comes to minorities, and people with disabilities their access to media is significantly reduced. Gender equality policies in media do not exist and media literacy policy is only nascent.

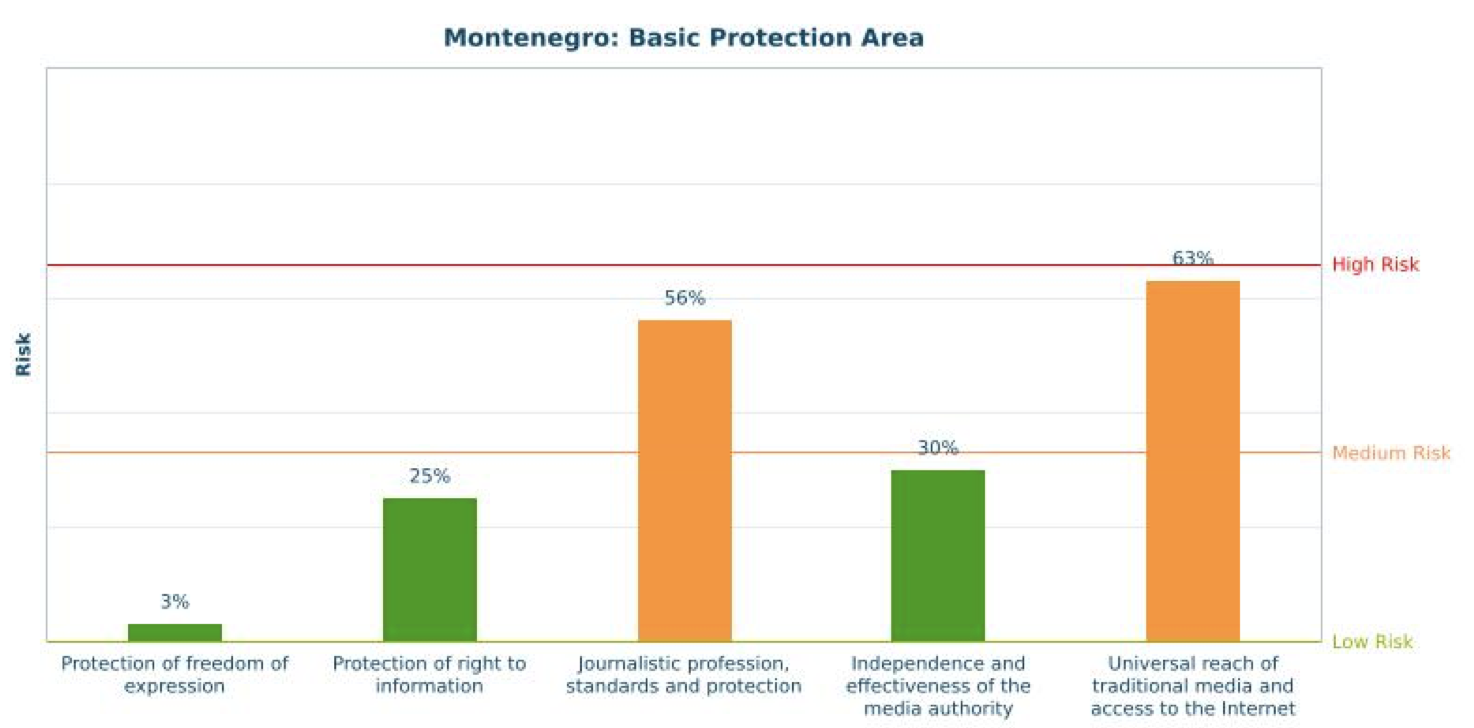

3.1. Basic Protection (35% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The indicator Protection of freedom of expression scores a low risk (3%) because the legal framework for protection of both freedom of expression and right to information in Montenegro is largely in line with European standards. It is though incomplete, and updates to the relevant national legislation are ongoing. Citizens are able to seek legal and other remedies in cases of infringement of freedom of expression through the ombudsman office, relevant courts, or media self-regulatory bodies. Complaints and appeals are rare, and they mostly refer to the right of response to previously expressed views in the mass media. Defamation is decriminalised and legal remedies allow for proportionate responses to the publication or broadcasting of defamatory statements. However, civil litigations tend to be slow and are seen as ineffective. In 2015, there was an initiative to adopt a special law on defamation, which would guarantee effective judicial procedures in cases of defamation in the media. In 2014, Montenegro’s Basic Court twice banned distribution of several editions of the tabloid Informer in an attempt to properly and timely sanction inflammatory content.

The indicator Protection of right to information also scores a low risk (25%), although there are challenges in this area. The problem remains the inaction of the administration which, for example, in 2015 left more than half of the requests for access to information unanswered; and the legal deadline for responding to the requests for access to information, which is 15 days, is often not respected. Another shortcoming is that the competent supervisory and appeal authority – the Agency for Protection of Personal Data and Free Access to Information, does not decide in cases where institutions do not provide any response to the request for free access to information.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection scores as medium risk (56%), mainly because access to the journalistic profession in Montenegro is absolutely open, with no legal or self-regulatory restriction or requirements in this regard. On the other hand, journalists are hardly represented at all through professional organizations (less than 20% of them are represented). A number of journalists’ organizations exist mainly on paper. They don’t provide any significant services to their members and have no actual influence.

This professional disunity is caused by political not professional reasons. Montenegrin media are deeply politicised and divided and that has a significant impact on journalists associations and their ability to develop into influential actors. Protection of journalists’ safety is another high risk indicator. Where attacks and threats take place many cases remain unsolved. In addition, working conditions of journalists are characterised by the lack of respect for media workers’ rights and average salaries are below the national average.

The indicator on the Media authority’s independence and effectiveness scores as low risk (30%) because legal regulations in place prevent political or commercial interference in management of this institution, which is financially independent, and transparent about its work. Its independence is jeopardised only by the Parliament which is responsible for the adoption of financial plans and reports of the Agency, and practices its right to modify them. There are, however, circumstantial indications that the regulator does not have either sufficient legal power or the will to perform sector analysis which could disclose potential economic or political pressures on media output.

The Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet poses the highest risk when it comes to Basic protection area (63% – medium risk, near high). Universal coverage of the PSM is guaranteed to the extent of 85% of population. The process of digitalisation in Montenegro is still ongoing, and currently digital signal coverage is 92%. The signal of national public service radio (RCG) covers 97 % of the population. The Top4 Internet service providers hold 96% market share, and net neutrality is not covered under any law.

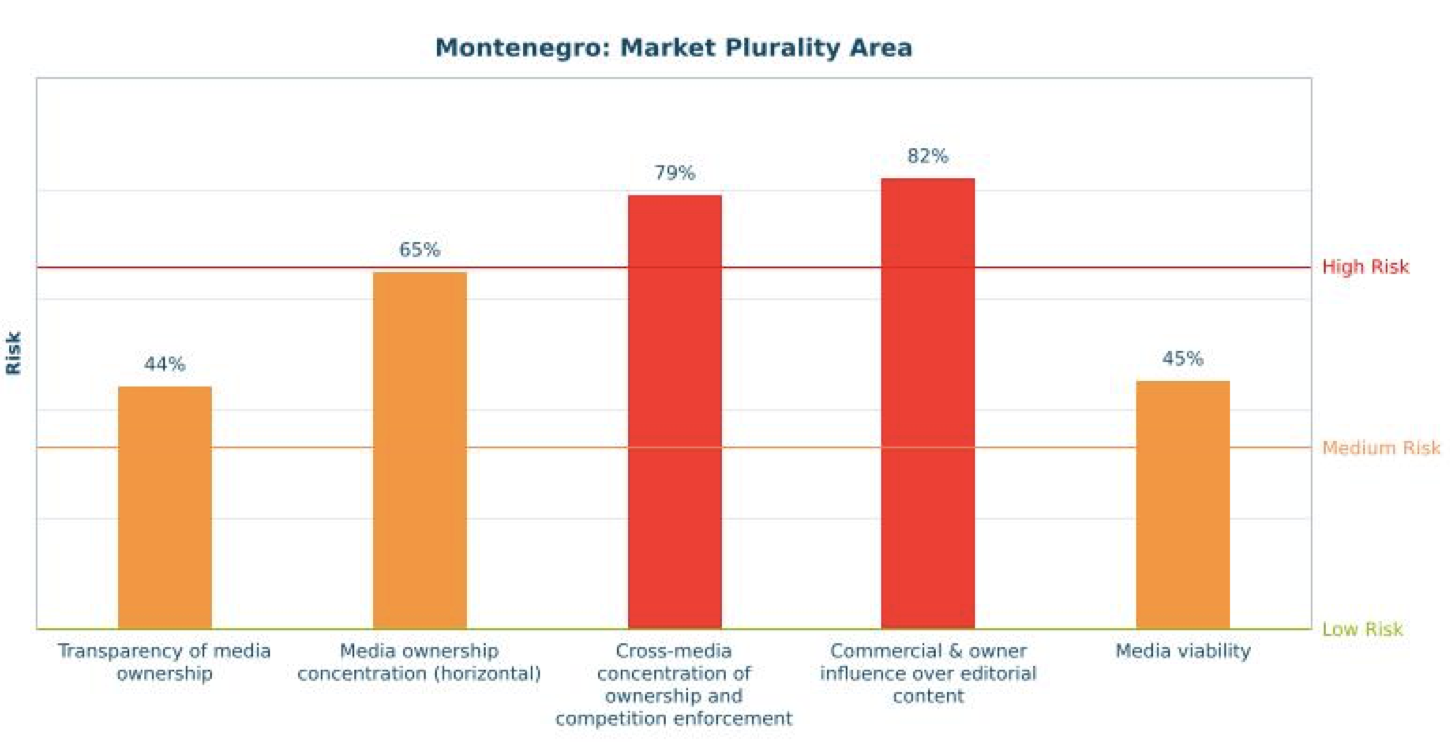

3.2. Market Plurality (63% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a medium risk (44%) because the media ownership data are for the major part available to the public through the regulatory agency in charge of the audiovisual sector. The print media registry is not public, and partial data on publishing companies are available only through the Central Registry of Commercial Entities of the Tax Administration. Also, there are no reliable verifiable data on media circulation and sold copies, although the Media Law requires it from publishers. Sanctioning provisions for noncompliance with transparency obligations exist only for electronic media. Internet portals are yet to be fully regulated in terms of ownership, transparency and content. The relevant bylaw was adopted in 2016. However, the level of media ownership transparency is disputable since three out of four commercial TV stations with national coverage (TV Pink M, TV Prva, TV Vijesti) are majorly owned by foreign companies, as well as three out of four local dailies. Their interests and partisan connections have often been questioned by media and civic sector organizations.

The indicator on Concentration of media ownership scores an almost high risk (65%), and the indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement high risk (79%). Media ownership concentration in audiovisual sector has been successfully safeguarded by the regulatory agency in recent years, where several interventions prevented broadcasters with national coverage to hold more than the legally allowed stakes in another national broadcaster and daily print media. However, analyses[3] provided by civil society organisations show that interventions were made for the sake of formal alignment with the law, and that the ownership has been transferred to other family members and closely connected persons, while the actual decision makers remained the same.

Horizontal concentration of ownership in the print media sector is not dealt with by the current legislation, although such concentration exists in the market. A special law on media concentration that would prevent both horizontal and vertical concentration in the media sector has been drafted but never adopted. In 2014, one owner gained control of two out of four Montenegrin dailies, and two online news portals[4].

The indicator on Commercial and owner influence over editorial content scores a high risk (82%), the highest when it comes to Market plurality area. There are no mechanisms granting social protection to journalists in the case of changes of ownership or editorial line. Moreover, there are no regulatory safeguards, including self-regulatory instruments, which seek to ensure that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief are not influenced by commercial interests.

The indicator on Media viability scores a medium risk (45%). Statistical data and analyses of media revenues are not publicly available and media largely do not respect their obligation to report their marketing revenues to the tax authorities. However, by comparing the available business results of five national broadcasters, including PSM, the data show that their aggregate revenues in 2015 saw an increase of 11%. However, in the overall context this cannot be taken as indicator of viability, since in 2013 and 2014 only one out of five national TV stations posted a profit. The increase in 2015 refers to PSM which is directly financed from the state budget.

There are no aggregate data available for the newspaper publishing sector, but according to financial results of the two major daily press companies Jumedia Mont and Daily Press in 2015, their revenues fell 8% and 23% respectively.

Online advertising saw a slight increase in 2014 and 2015, reaching, however, a modest 7% of the total advertising spending.

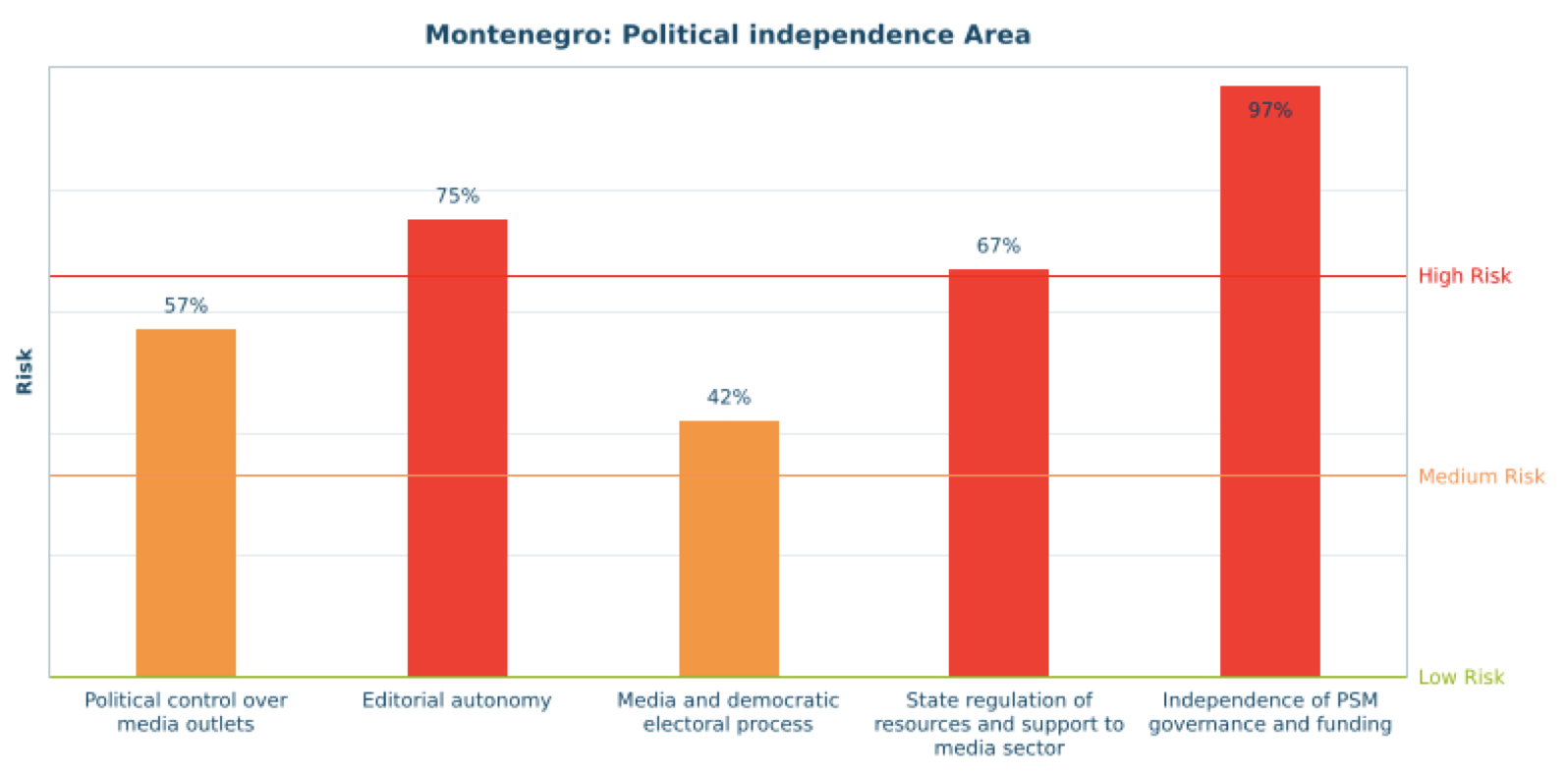

3.3. Political Independence (68% – high risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicator Political control over media outlets scores a medium risk (57%). Audiovisual regulation prevents political parties becoming broadcasters or sponsoring audiovisual media programmes, but there are no legal restrictions to thwart indirect partisan control over the commercial print media, news agencies and online media. There is no evidence of direct political control over audiovisual media, due to the lack of systematic monitoring, but the partisan influence is evident. Studies on media financing in Montenegro produced by civil society organizations reveal potential clientelistic relations between the media and the Montenegrin government. In such liaison, the Government is believed to channel money and create favourable business environment for certain media outlets, which then in turn represent ruling party in positive light, and often run campaigns affirmative of the ruling party’s political interests.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a high risk (75%) because media laws do not guarantee any autonomy in the appointment or dismissal of editors-in-chief. There are indications that in the media which are under minor or major political influence, political factors interfere with the selection and removal of editors-in-chief. This is especially evident in national public services media, as well as in local public service media. The provisions on editorial independence of the news media are contained only in the Code of Journalists, but the respect for this document has never been achieved to a significant extent since there are no strong self-regulatory mechanisms in place. Systematic influence on editorial content in the news media is evident. At one side, the impact is shown by the fact that content, the selection of topics and editorial approach to topics, substantially reflect the propaganda agenda of the government. On the other hand, political influence is felt in over-stressing the bad aspects of government and unbalanced approach to topics.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a medium risk (42%). During elections PSM provides all contestants with free and equitable access so as to secure fair representation of political viewpoints in news and informative programmes. This sole fact, however, does not secure unbiased reporting. Private TV channels, without exception, are not politically neutral and have their political favourites, which is particularly evident during election campaigns.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to media sector scores a high risk (67%). The allocation of frequencies is conducted through an open call with clearly set rules and criteria. In recent years there were no complaints on spectrum allocation. The only direct support to private media from the state goes to commercial radio stations and is distributed through an open call by the regulatory body. The funds are collected from fees paid by drivers through obligatory car registration. State aid to commercial media is not regulated whatsoever, and there are reports from the civic sector that it poses a threat to market competition. What additionally makes this indicator a high risk one is the fact that regulators do not perform any sector analysis to disclose informal economic pressures on independent reporting. Moreover, there are no official or public data on viewership or readership shares to assess whether the allocation of state subsidies and advertising is done by this criteria.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding with score of 97% represents the highest risk not only in this area but in the entire country Monitor. National public broadcaster is financed directly from the state budget and its revenues are double the total revenues of all other electronic media in the country. There are no regulatory safeguards ensuring that State funds granted to PSM do not exceed what is necessary to provide the public service. The amendments to the law on the public broadcasting service that would partially provide for such safeguards were drafted in late 2014, but not yet adopted. Appointment procedures for management and board functions in PSM only nominally guarantee independence from government or other political influence. Many of the Board members, appointed by Parliament, come from institutions financed by the state where the influence of the long ruling Democratic Party of Socialists is dominant. The composition of the Council of the national public broadcaster RTCG is not recognized as professionally strong enough to implement measures for raising the quality of PBM programme and its functioning.

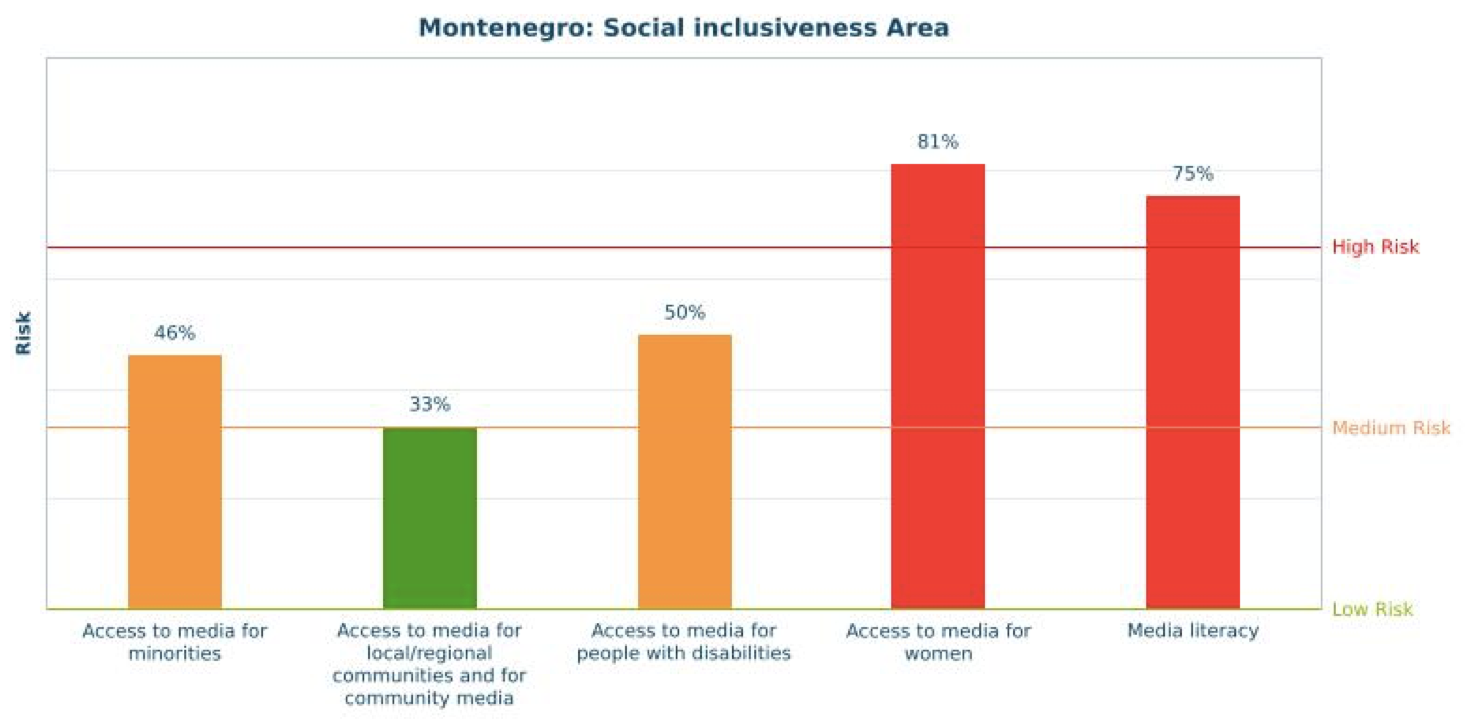

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (57% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The Monitor indicates that Access to media for minorities is at medium risk in Montenegro (46%). Montenegrin reality is specific because the minorities are not clearly defined. The Constitution defines minority rights, but does not stipulate who minorities actually are. This is an open issue since the referendum on independence and the break-up of state union with Serbia in 2006. According to the 2011 census, Montenegrins make up 44.9% of the population, and Serbs 28.7%. Another specificity is that the Albanians and the Roma are the only minorities whose language is significantly different from the ones of the majority of the South Slavic ethnic groups. These two minority groups have specially designed radio and TV programmes on national PSM in their own languages. Newscasts in Albanian are broadcast every day, while that in the Roma language is broadcast weekly on the radio, and once a month on TV.

Other ethnic minorities do not have specific programmes on PSM, and have sometimes publicly voiced their dissatisfaction in this regard. However, due to the fact that Montenegrin, Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian are very similar with some lexical and phonetic differences, makes it difficult to determine their proportional representation in the audio-visual media.

Access to media for local and regional communities, and for community media is a low risk (33%). The category of “community media” is not recognized in Montenegrin media legislation. However, local and regional media have, by law, access to all media platforms, under the same conditions. Authorities support regional/local media through a variety of policy measures and subsidies. In particular, the Agency for Electronic Media (AEM), through its Fund for assistance to commercial radio broadcasters, helps local and regional radio broadcasters.

The national PSM also has a correspondent network, but there are no fixed rules in terms of the amount given for representation of specific local or regional communities in the overall programme. The PSM has no legal obligation to have local correspondents or to establish regional RTV studios that would produce regional programmes and programmes in the languages of national minorities and other minority communities.

Access to media for people with disabilities is at medium risk (50%). Media laws define the obligation to produce and distribute content for persons with disabilities, and to promote their human rights. Media laws impose an obligation for media to produce content specifically accessible to people with visual and hearing impairments, but, in practice, these rules are very poorly implemented. Also, there is a legal obligation for on-demand audiovisual media to a fixed percentage of content that must be accessible for people with disabilities. However, in practice PSM and commercial media do not comply with these obligations.

Access to media for women is at very high risk (81%). Media in Montenegro, including PSM, still do not recognize the importance of gender mainstreaming. The PSM has no gender equality policy and the PSM management board consists of eight men and only one woman. Nevertheless, the gender structure of employees is well balanced. The national PSM (RTCG) in early 2016 employed 212 journalists, of whom 120 were women and 92 men.

The indicator on Media literacy scores high risk, too (75%).The policy on media literacy in Montenegro is underdeveloped. There is no overarching media literacy policy but sector-based attempts to address the issue. These attempts are only nascent and tend to be fragmented. The reform of secondary education in 2009 introduced Media Literacy as an optional one-year course in the second or third grade of grammar school. The researchers were not able to find evidence for any systematic initiatives regarding informal media literacy education, either for children or adults.

4. Conclusions

The current legislative framework in Montenegro mostly provides the essential preconditions for the development of media pluralism. However, the relevant institutions, and main political and social actors are not investing sufficient efforts in creating a climate of respect for the law and the protection of guaranteed freedoms. Hence, the author concludes that:

- It is necessary to improve the enforcement of legislation in the area of free access to information, especially to eliminate the general problem of silence by the administration which essentially means ignoring requests for information. It is most common and the most obvious obstacle to free access to information.

- Journalists need to create a strong professional association that will provide protection and social security for them.

The rules for media market entrance in Montenegro are liberal, with limitations that are in line with European standards, and media ownership is mostly transparent. Ownership concentration is present, and the impact of owners on editorial independence and media content is strong. Hence, the author recommends to:

- It’s necessary to pass a special law to regulate the issue of allowed media concentration so as to preserve the plurality of views.

- To develop legislative mechanisms that will provide more editorial independence and social protection to journalists in the case of a change of ownership or of the editorial line.

The current legislative framework does not prevent political influence on the media and their editorial policies. The public media financing scheme jeopardizes their independence, and the total absence of regulation of state aid to media allows the ruling circles to interfere with the editorial independence of commercial media.

- Since the current model of direct state financing of the national and local PSM carries the risk of increased political interference on editorial policy, it is necessary to look for new models of financing which would ensure better protection of PSM from political interference.

It is necessary to pass a special law to regulate the issue of financial or other support to private media by the government and public institutions.

Local communities have adequate access to the media, but this is not the case with other groups, especially with people with disabilities and women. Media literacy policy is only nascent. Hence, the author recommends to:

- Develop specific stimulating measures that will enable a greater presence of people with disabilities and women in the media;

- make media literacy an integral part of the curriculum in primary and secondary schools. Informal media literacy programs for youth and adults should receive financial support from the state.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Dragoljub | Vuković | Team leader | X | |

| Daniela | Brkić | Consultant researcher | ||

| Milica | Minić | Interviewer |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Vladan | Mićunović | Representative of a journalist organisation | Montenegro Media Institute |

| Tea | Gorjanc Prelević |

Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Human Rights Action |

| Nikola | Marković | Representative of a publisher organisation | Daily newspaper ‘Dan’ |

| Marijana | Kadić Bojanić |

Representative of a broadcaster organisation | TV Vijesti |

| Jadranka | Vojvodić | Representative of media regulators | Agency for Electronic Media |

| Božena | Jelušić | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | |

| Ana | Vujošević Nenezić |

Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the medi | Center for Civic Education |

Annexe 3. Summary of the Stakeholders Meeting

Date: 9 December 2016

Place: Podgorica (Montenegro Media Institute)

List of participants: Dragoljub Vuković, team leader, Daniela Brkić, consultant researcher in country team, VladanMićunović, director of Montenegro Media Institute, Tea GorjancPrelević, executive director of NGO Humane Rights Action, Jadranka Vojvodić, deputy director of Agency for Electronic Media, BoženaJelušić, professor of media literacy, PhD Jelena Perović, expert on media literacy, Maja Raičević, director of Center for Women’s Rights, Ana VujoševićNenezić, media researcher in NGO Center for Civic Education and MirsadRastoder, editor at National Public Radio.

Key topics discussed:

The meeting participants were informed about the results of the Media Pluralism Monitor related to Montenegro and the final report drawn up by a local team of researchers. The discussion was focused on the extent to which indicators reflect the actual situation in the Montenegrin media reality. The general attitude was that the report gave a solid overview of the current situation and pinpointed the main issues burdening media pluralism in the country. During the meeting, it was underlined that in Montenegro the legislative framework was largely aligned with the European standards, but that the MPM2016 report could have stressed the fact that the application of international standards in legal proceedings is poor.

Meeting participants also pointed to a tendency within the ruling political parties and one part of the media community to present the decriminalisation of defamation as something that has not given good results in practice and prepare the ground for the re-criminalization of libel. The discussion highlighted the importance of improving the legislation in the field of media, so as to narrow down the space for non-institutional influence on the media and journalists. The importance of legal regulation of media financing from public funds was especially accentuated.

Conclusions:

Conclusions presented in the final narrative report, according to the participants of the meeting, could be extended so as to include the following:

1) It is necessary to improve the set of media laws in order to further promote and improve the application of court practice of the European Court of Human Rights in exercising and protecting the right to freedom of expression and other rights guaranteed by the Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (right to protection of privacy, reputation, etc.);

2) In order to ensure transparency of public funding (state advertising, subsidies, tax and other relief schemes), it is necessary to legally regulate transparency related rights and obligations of providers of public funds (state bodies and institutions or companies owned by the state), media or agents (advertising and PR agencies).

Other remarks: The meeting participants pointed out that the final narrative report should contain the time framework of data collection. This is because of the changes in the legislation that have been adopted in July 2016 and which have not been covered by the report.

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSC 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

[3]D. Brkic, Media Ownership and Financing in Montenegro: Weak Regulation Enforcement and Persistence of Media Control, Peace Institute, Institute for Contemporary Social and Political Studies, Ljubljana, 2015, available at: https://mediaobservatory.net/radar/media-integrity-report-media-ownership-and-financing-montenegro

[4]M. Perovic Korac, Invest in Media, Earn in Tourism, 2016-03-06, https://mediaobservatory.net/investigative-journalism/interests-greek-businessman-petros-stathis-montenegrin-media-invest-media