Download the report in .pdf

English – French

Authors: Raphaël Kies, Kim Nommesch, Céline Schall

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Luxembourg, the CMPF partnered with Raphael Kies (University of Luxembourg, PI) Celine Schall (University of Luxembourg) and Kim Nommesch, who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Luxembourgish team organized a stakeholder meeting, on February 2nd 2017 at the University of Luxembourg. Summary of this meeting and more detailed explanations are given in Annex 3.

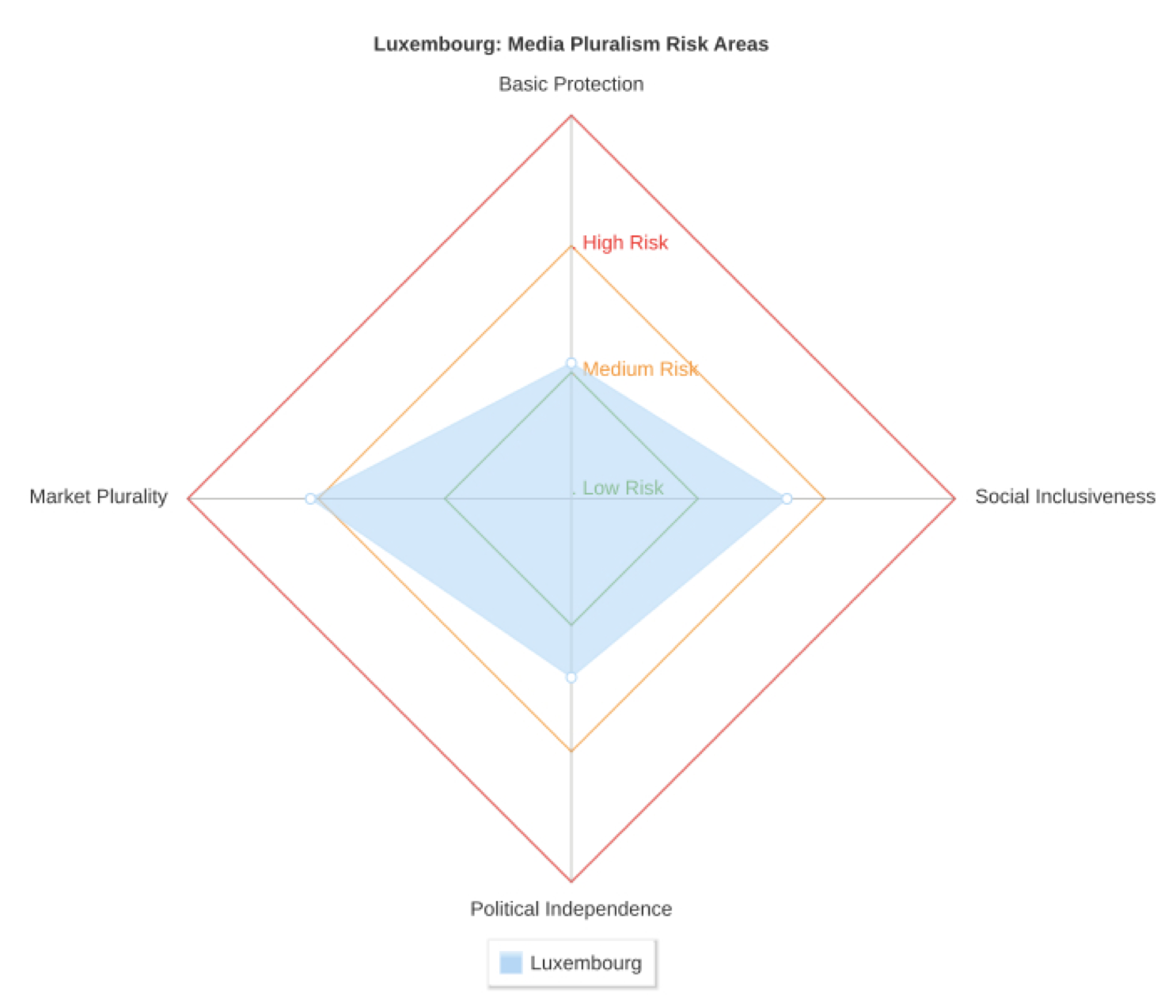

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0 to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

With 562,958 inhabitants, Luxembourg is one of the smallest, but also richest and most politically stable countries in Europe. However, demographic and social complexities are increasingly leading to social and political tensions. The country is largely dependent on foreign working force (the number of inhabitants being largely insufficient to cover labour requirements) which explains the record high proportion of resident foreigners (46,7% on 1st January 2016) and cross-border workers (around 160,000. This demographic feature has created political and social challenges not only in terms of social cohesion, but also of democratic legitimacy.

The linguistic situation in Luxembourg is highly complex and peculiar as it is characterized by the practice and the recognition of three official languages (also referred to as administrative languages): French, German, and the national language Luxembourgish, established by law in 1984. Many other languages are spoken, in particular Portuguese (the largest foreign community) and English (essentially spoken by employees of financial institutions and international organisations). While there are several commercial radio channels targeting this multilingual public (e.g.: Radio Latina for the Portuguese speaking community or Radio ARA for the French, English and Italian speaking communities), the PSM (i.e. the sociocultural radio) and RTL (the main commercial radio and television company) broadcast mainly in Luxembourgish.

If we accept the view of the Minority Right Groups International Organisation[2], that foreigners living in Luxembourg are linguistic minorities, Luxembourg presents the paradoxical situation in which the sum of its minority groups will soon become the ‘majority’. In 2016, almost half of the local population did not have Luxembourgish nationality and the ratio of foreigners continues increasing. The largest minority groups are Portuguese (16,2%), French (7,2%), Italian (3,5%), Belgian (3,4%) and Germans (2,2%)[3]. The law does not guarantee access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities, but there is a large offer especially in print media as well as in radio broadcasting targeting linguistic minorities.

The media market in Luxembourg is surprisingly rich compared to its size and the number of inhabitants. The country exercises an important role in the management of international media concessions through RTL Group. The print sector includes five daily newspapers, one free daily newspaper, 23 magazines, as well as weekly and monthly newspapers. The TV market is dominated by RTL and there are six TV stations (four local and two national), but residents also have access to channels from the neighbouring countries. RTL is the biggest broadcaster and has a “public service mission”, but is not a “public service medium”. There are about seven private radio stations with national coverage and only one radio broadcaster (Radio 100,7) that is officially recognized as a public service medium (PSM). Internet coverage is very good across the country. This apparent diversity masks a very important (horizontal and cross-) concentration of the market, since the majority of print media belongs to three publishing companies (of which two cumulate 55% of the readers) and the audiovisual sector is dominated by two groups (the concentration of the audience for the first four owners of television channels is 68.2% for 2014/2015 and the audience concentration for the first four owners of radio channels amounts to a total of 78.6% for the same period[4]).

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

According to MPM2016, Luxembourg presents medium risk for Basic Protection, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness areas but high risk for Market Plurality. These mixed performances can be explained mainly by the small size of the country, its demographic structure (high percentage of non-Luxembourgish residents), its prominent role in the international “market of concessions” and the lack of critical and independent reports on the national media legislation, market and practices. All in all, these special conditions show why Luxembourg is a peculiar case where pragmatism defines the media and electronic communications policies. This approach “justifies” the lack of human resources and the effectiveness of national authorities, the absence of an adequate national media offer (for the multilingual resident population, especially in the audiovisual sector) and the presence of a highly-concentrated media market. Thus, while the print media – and to a certain extent the radio sector – is diverse compared to the geographical size, the audiovisual sector is dominated by RTL Group which broadcasts mainly in Luxembourgish. Lastly, it should be noted that in contrast to the audiovisual media, the majority of the newspapers are affiliated to a political or interest group, although it should be noted that we observed a trend towards more editorial independence over the last years. The pluralism in the print press could so far only be guaranteed due to a generous direct and indirect press subsidies system.

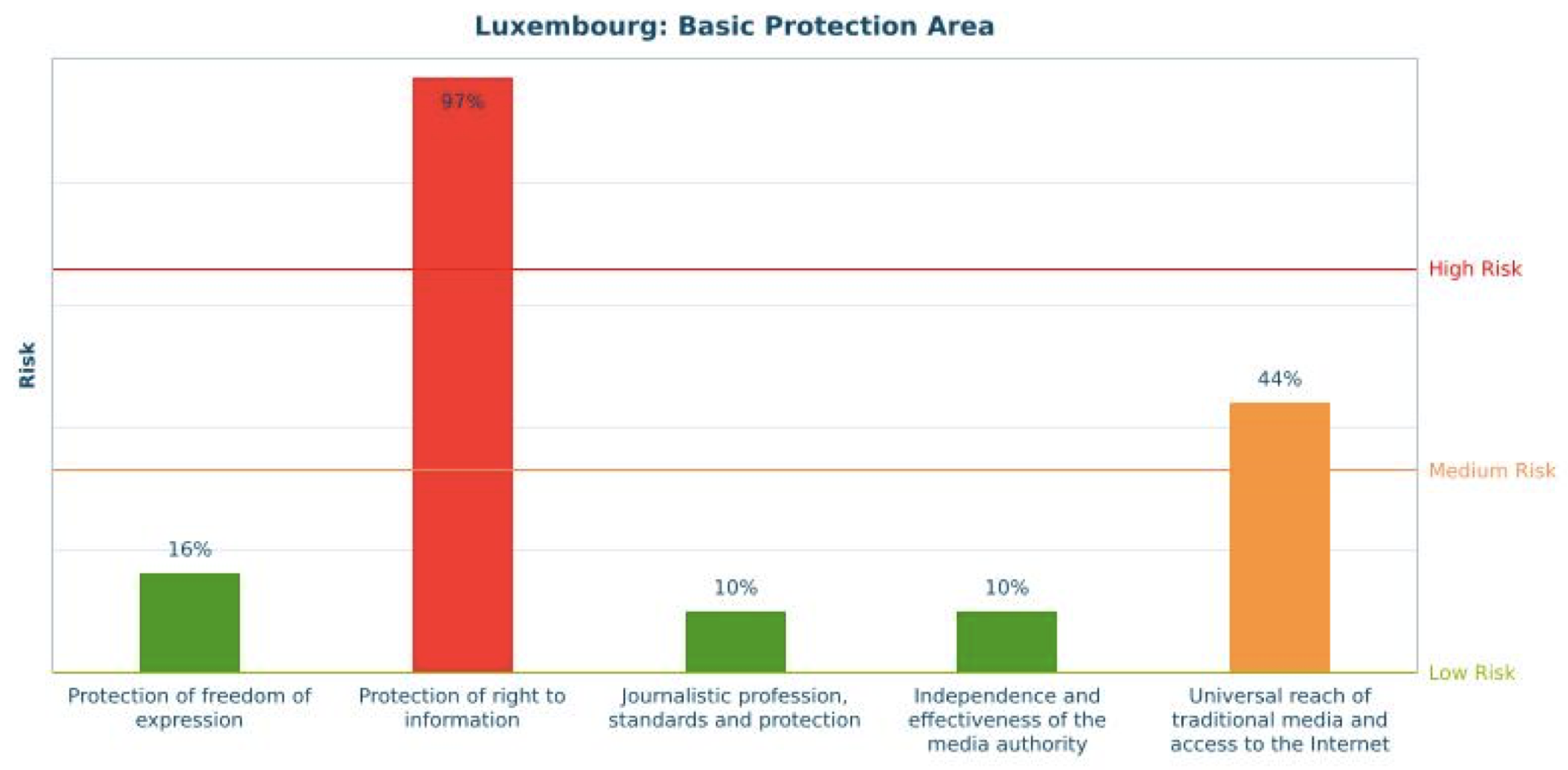

3.1. Basic Protection (35% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The indicator Protection of freedom of expression scores a low risk (16%). Freedom of expression is explicitly recognised in the Constitution and protected by national law. Luxembourg has also signed and ratified important international treaties related to this matter. The MPM score is in line with the ranking of the Freedom House Index, that gives the country the highest ranking in terms of civil liberties and political rights; on a general basis, the risk of violation of freedom of expression is low indeed. Defamation is not decriminalised, but criminal defamation prosecutions against the media, and even more convictions, have been rare and not widely publicized until the recent affair concerning an interview with the former director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in a prime-time show[5]. The material was manipulated in a way that the director considered to be defamatory. Political tensions emerged and contributed to the resignation of both the director and the CEO of RTL. The incident raised questions not only about the integrity of the media profession, but also about the links between the government and the broadcaster as RTL is indirectly financed by the state for fulfilling a public service mission.

The indicator Protection of right to information scores a high risk (97%). The right to information is not legally enshrined. The Ministry of State has elaborated a new draft bill on “open and transparent administration”, which has been widely criticised by civil society organisations as being too restrictive. It seems to not bring any fundamental change compared to the previous draft bill on the access of citizens to documents held by the administration. It contains numerous exceptions and the administration keeps important powers in terms of deciding when to issue the information. In addition, the Minister for Communications issued at the beginning of 2016 a circular letter stating that all requests need to be addressed to the communication officer, thus further restricting the work of journalists.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection scores a low risk (10%). In practice, the journalistic profession is very open. Journalists are legally protected in cases of editorial change, and their sources are well protected as well. However, specific regulations preventing commercial influences on editorial content are missing. The journalists’ associations – which count less than half of the journalists as their registered members – offer only limited protection in the case of threats against editorial independence or professional standards. In recent years, the protection of sources has worked fairly well and there have not been any reported physical or digital threats against journalists. However, some declare that they feel increasingly put under pressure by advertisers. Some national newspapers have practices that could be described as deceptive (advertorials) in spite of the legal prohibition. Many journalists also work in precarious conditions as they do not have fixed contracts. Finally, a French reporter was accused in 2015 of complicity in the breach of business secrecy and professional secrecy for publishing secret tax documents obtained via a former employee of PwC (cf. LuxLeaks). He was acquitted, but the state prosecutor has appealed this verdict. The case raises the question of press freedom and has caused uproar in the international community.

The indicator on Independence and effectiveness of the media authority scores a low risk (10%). ALIA (Independent Luxembourgish Audiovisual Authority) is the newly created independent media authority (2013) which unifies the formerly fragmented regulatory landscape. Its independence (including its selection procedures) is guaranteed by law, but the authors estimate that the selection procedures may become more transparent in practice. Although financial allocation procedures are transparent and objective, the annual budget is largely insufficient to provide enough human resources to correctly perform the (numerous) missions. ALIA is composed of 2.75 permanent employees who are also responsible for monitoring around 50 audiovisual concessions[6] in several countries, without mentioning VOD services. It does not provide the means to effectively supervise the implementation of legislation and the respect of provisions in the book of specifications – not only because of the relatively high number of broadcasters with a Luxembourgish license, but also due to the language barriers. Finally, some stakeholders think that the budget is adequate, because, according to them, the media authority’s mission does not require the authority to supervise all broadcastings, but should mainly respond to complaints.

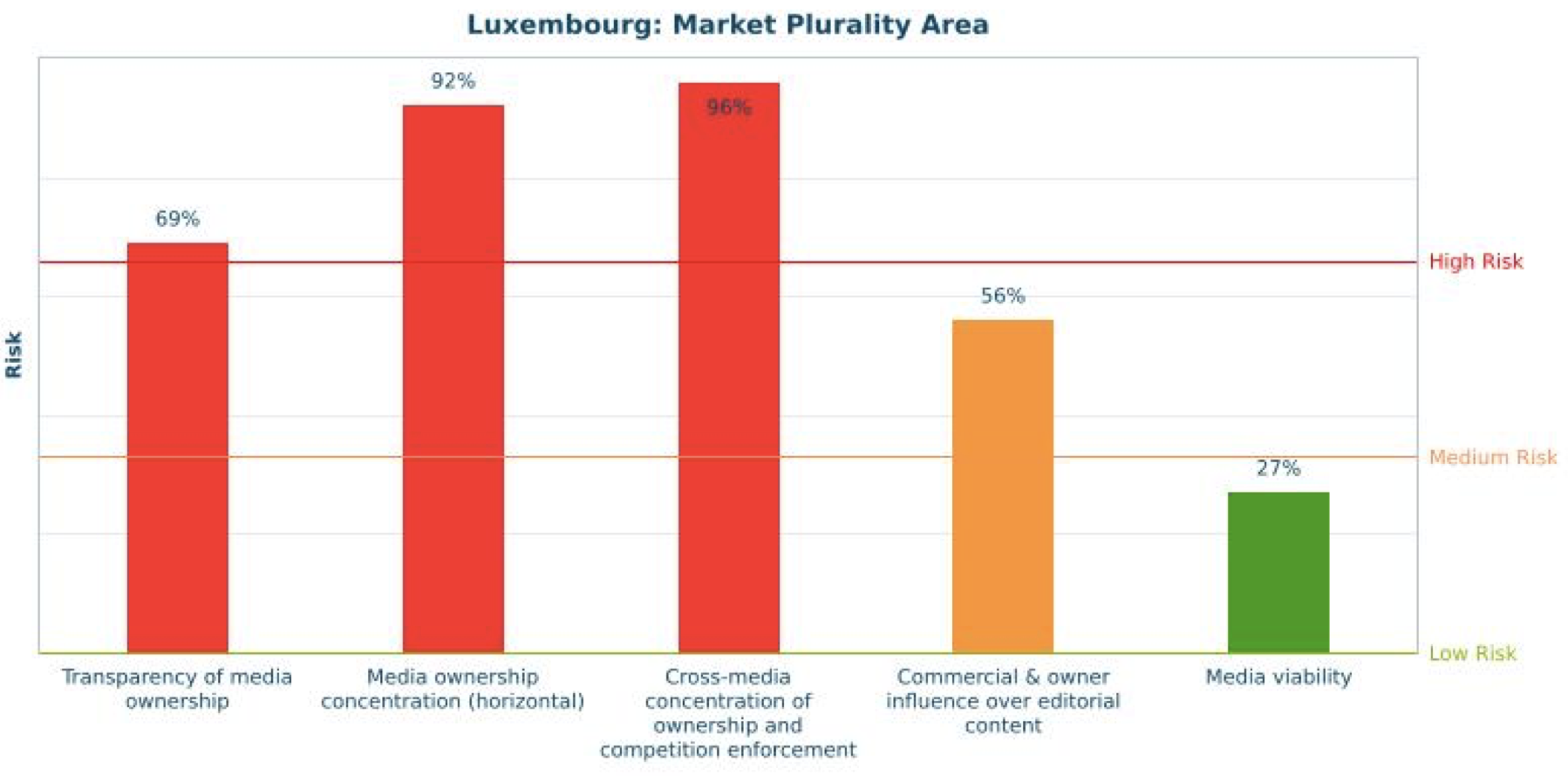

3.2. Market Plurality (68% – high risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a high risk (69%). There is limited transparency in terms of media ownership in the print media sector as the law obliges the latter to publish their ownership structures only when one shareholder holds more than 25% of the company. Concerning TV and radio the situation is even more critical as the law does not contain any provisions concerning the ownership structure. There is moreover no legal duty to inform the public about changes related to the ownership structure in the press or audiovisual sector.

The indicator on Concentration of media ownership also scores a high risk (92%). The media market is one of the most concentrated in Europe: three media companies clearly dominate the media market (two for the radio sector – RTL and Saint-Paul Group –, two for the press sector – Editpress and Saint-Paul Group – and one for the TV sector – RTL Group) while one site largely dominates the Internet content intermediaries’ sector (Google.com). The press sector is very specific as it benefits from an important direct and indirect public subsidy (this explains the presence of five different daily newspapers). All in all, the four main television owners (including non-Luxembourgish ones) accumulate 59% of the national audience, the four main radio owners 75%, and the four main press owners 56% (we have no figures for internet content providers). This high concentration level can be explained by the very limited market size and the absence of specific legal provisions aiming at controlling media concentration[7]. The role of the competition authority is to control mergers in cases of abuse of a dominant market position, but this concerns the economic market in general, without taking into account the specificities of the media sector. Media concentration is not seen as a problem by lawmakers, but as inevitable due to the very small size of the market (about 563,000 inhabitants) and its linguistic fragmentation (over 45% of residents are foreigners). This being said, it needs to be considered that the majority of the population also consumes media (especially TV) from neighbouring countries. Thus, French-speaking or German-speaking residents watch for example German ZDF (10,8%), ProSieben/Sat.1 (12%) or French TF1 (10,7%). Many also read French or German print media.

The indicator Concentration of cross-media ownership also scores a high risk (96%). Luxembourgish law contains no limit or specific criteria that would allow control of cross-media concentration. Major groups (Editpress, Saint-Paul and RTL Group) are present in several media sectors (print media, radio, television and the Internet). The competition authority is seized only if an abuse of a dominant market position is observed, but it does not take into account the specificities of the media sector.

The indicator Commercial and owner influence over editorial content acquires a medium risk (56%). In case of changes of ownership or editorial line, journalists are granted social protection by law. If a new editorial line conflicts with the personal convictions of the journalists, the latter may put an end to his contract without prior notice. In this specific case the executive board cannot contest the full unemployment benefits of the journalist. The deontological code for journalists requires journalists and editors to be independent of any commercial interest and to not accept any benefits or promises that could limit their independence and the expression of their own opinion. Advertorials (i.e. advertising that could be confused with editorial content) are prohibited by the consumer code, but are still widely published, especially in the free press. There are no national laws or self-regulatory instruments ensuring that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief are not influenced by commercial interests. Journalists who were interviewed for this study estimate that commercial demands are frequent, but do not prevent them from doing their work in an independent way.

The indicator on Media viability scores low risk (27%), which may seem misleading as the press faces serious challenges in face of the changing reading habits and the rise of digital media. It should be taken into account that many questions could not be answered as there is no publically available data that would allow to evaluate the evolution of the revenues in the audiovisual and print media sector. As far as state subsidies are concerned, the government has so far granted various international licenses to RTL Group in exchange for providing a public service while newspapers benefit from generous direct and indirect public subsidies. Even if it is challenging to provide an overall evaluation of the public support schemes since they differ according to the sector, it is considered that they overall contribute to maintain diversity in the media landscape, especially in print media.

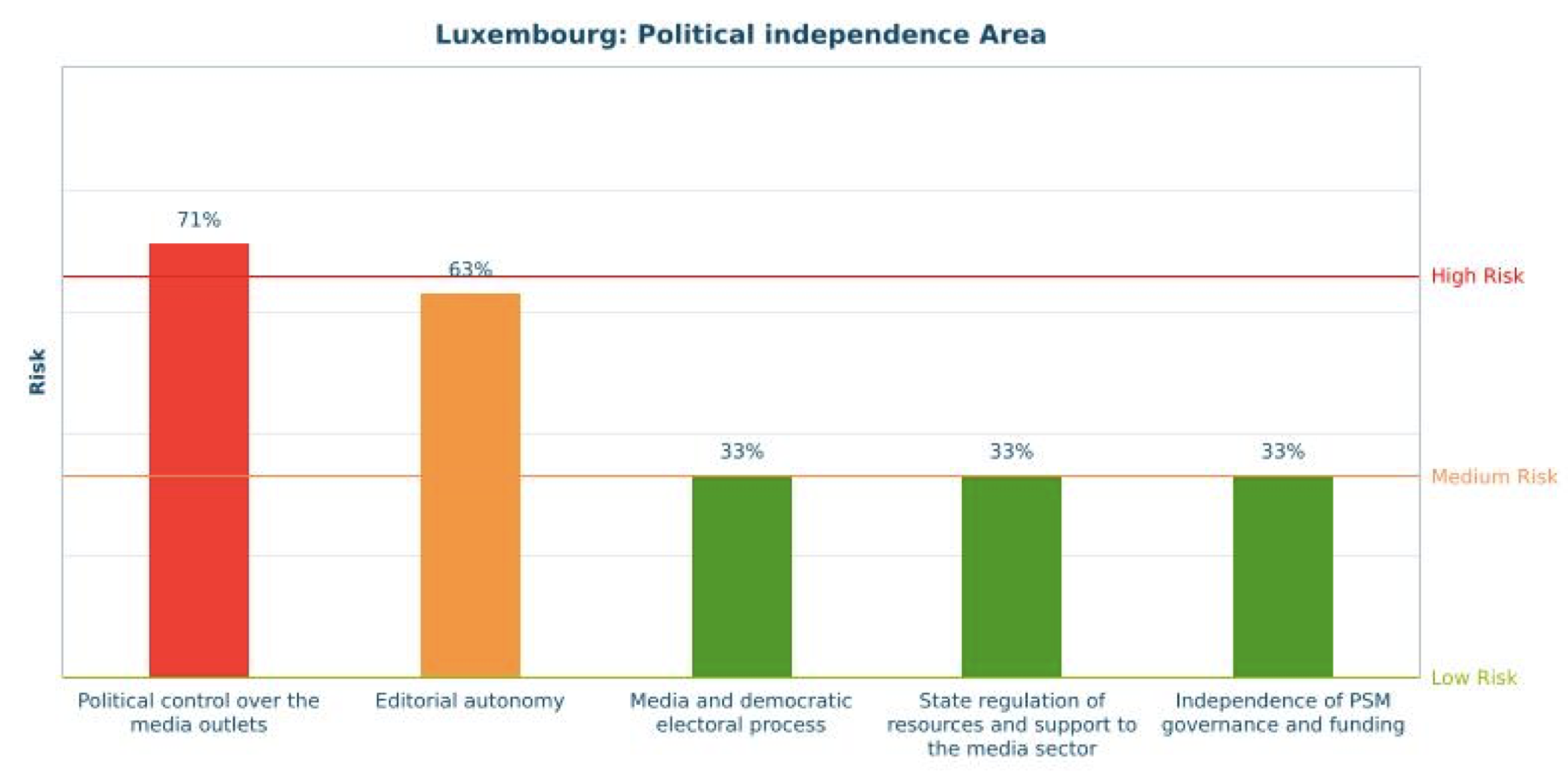

3.3. Political Independence (47% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Political control over media outlets scores a high risk (71%). The law does not regulate conflict of interests between owners of media and ruling parties, partisan groups or politicians. There is no distribution group[8], TV or radio channel that belongs to a political party. Yet, the public service mission provided by the concession contract between CLT-UFA (i.e. RTL Group) and the government ties these two actors. In addition, according to custom, a representative from each of the three most important political parties becomes a member of the executive board of CLT-UFA. In contrast to the audiovisual sector, most newspapers are ideologically close to a political party or interest group. There are two main groups for print media (Editpress and Saint-Paul Group). Luxemburger Wort is the largest daily newspaper and similar to other publications such as Contacto and Télécran, it is part of Saint-Paul Group whose main shareholder is the archdiocese of Luxembourg. Traditionally, it has had close links with the dominant political party, the Christian Social People’s Party (CSV), which has almost uninterruptedly been in power from Second World War to 2013. The previous chair of the executive board was the former vicar general while the current chair is the former CSV budget and finance minister. Thus, the link to CSV remains. However, recent developments show that the Luxemburger Wort gains more distance to its ideological counterparts. Members of the executive board of the newspaper Lëtzebuerguer Journal, owned by the Editions Lëtzebuerger Journal SA, are representatives of the Liberal Party and the current chief editor worked for the Liberal Party before joining the editorial team of the newspaper. However, in 2012 it was decided that the editorial policy should remain liberal, but independent from the party. The second most important newspaper, Tageblatt and other newspapers such as Le Quotidien, Correio, Jeudi, L’Essentiel (free newspaper), are part of Editpress Group. The majority capital of Editpress is held by Centrale du LAV, the predecessor of the biggest trade union today (OGBL). It is generally believed to have socialist leanings and to be close to the country’s second most important political party (LSAP). The former chairman was also president of OGBL[9]. The communist party also publishes its own newspaper while there are some more independent newspapers: paperjam (Maison Moderne), but considered to be close to the business world, woxx (managed by a cooperative), forum (published by a non-profit association) and Lëtzebuerger Land (Editions Lëtzebuerger Land). It should also be mentioned that there is a satirical newspaper Feierkrop and Lëtzebuerg Privat. The latter is tabloid newspaper not recognised by the Press Council but enjoying a large readership.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a medium risk (63%). Despite the absence of common regulatory safeguards that guarantee autonomy when appointing or dismissing editors-in-chief and reports of independent bodies commenting the situation, it is assumed that the political influence is more limited today. However, some links cannot be ignored: The current editor-in-chief of Lëtzebuerger Journal worked for the liberal party before joining the newspaper. The editors-in-chief of the other newspapers have not worked for any party directly. However, the editor-in-chief of the most important national newspaper (Luxemburger Wort) worked as a close advisor for the former Prime Minister (CSV) before joining the media company that is said to be close to the CSV party. During the last years there has been progress concerning the independence of editorial policies, but considering that representatives of certain interest groups and political parties control the executive boards of the media groups, political influence cannot be excluded.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a low risk, but on the border of medium risk (33%). In general, a fair access to different political views is protected by 1991 modified law on electronic media (art. 12 for audiovisual services and art 15 to 19 for radio services), and by the code of ethics elaborated in 2006 by the Press Council. During election periods, media law (including concession contracts) imposes general rules that aim at guaranteeing competing parties the same access to airtime on PSM channels and services in all types of elections. More precisely, the electoral campaign is planned and supervised by a consultative commission on ‘electoral campaigns’[10]. It should be said that the control of compliance with these rules is rather limited in relation to its scope (it is related only to the official events of the campaign) and to its resources (only one person checks whether the speaking time is allocated equally among all the candidates). Complaints concerning the non-respect of pluralism must be directed to ALIA, but this authority is not competent for complaints concerning the non-respect of the informal convention between the government, the parties and the PSM. Despite limited control in electoral campaigns, and in the absence of official complaints, the authors estimate that the regulatory safeguarding as well as political coverage by PSM and commercial channels is fair, balanced and correctly implemented. There are however no legal restrictions with regards to political advertising as the same rules apply for commercial and political advertising. Moreover, there is no regulatory framework requiring to explicitly informing the public that the message is a paid political advertisement.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector also scores a low risk, bordering with medium risk (33%). The legislation provides transparent rules on spectrum allocation and on the distribution of direct subsidies to print media outlets. It should be underlined that only newspapers benefit from direct subsidies through the amended law on the promotion of print media of 1998. Currently, the government is elaborating a new policy on distribution of direct subsidies as the existing scheme does not include online media. In contrast to the newspaper sector, legislation does not provide any rules for the distribution of direct subsidies to audiovisual media. There are no rules on state advertising, but official notices (“avis officiels”) are published in every daily and weekly printed newspaper that also receives press subsidies. The publishing of these notices can be considered as another type of indirect subsidy, similar to other existing ones such as preferential rates on postage. Some stakeholders consider these are not indirect subsidies, as the State receive a service in exchange.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding also scores a low risk, close to medium risk (33%). The country has only one public service (radio 100,7) financed by the state. There are objective and transparent appointment procedures for the management and board functions of the PSM radio defined by law. However, there are some inherent contradictions as the government directly appoints the members of the Executive Board, and indirectly the director whose mandate is not limited in time. Moreover, the budget as well as the organization structure has to be approved by the competent ministry. Despite these contradictions, the PSM is independent in its reporting, but only a very small, and mostly well educated, part of the population belongs to the audience. CLT-UFA has signed a concession contract with the government and has agreed to assume a public service mission (the last agreement was signed in 2007 and runs for a period of 13 years). Yet, despite this mission, it remains a commercial channel which is why the state cannot regulate appointment procedures. However, by custom, a representative from each of the main political parties is part of the CLT-UFA executive board.

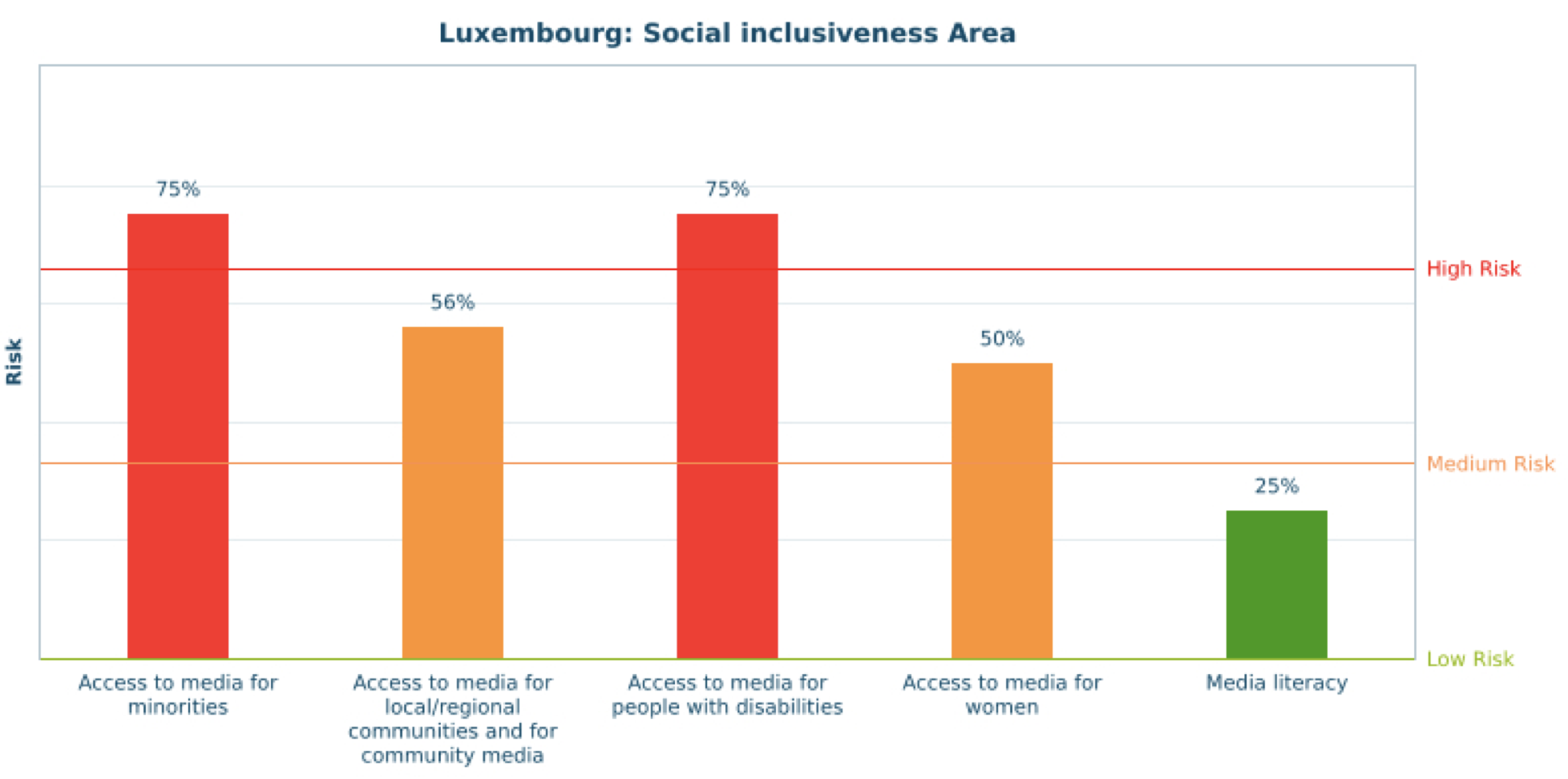

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (56% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator on Access to media for minorities scores a high risk (75%). Luxembourg does not have any minorities in the sense of the Council of Europe’s definition (which implies that such minorities should have Luxembourgish nationality), but has important linguistic minorities as almost half of the population are foreign residents – among them a large number that does not speak Luxembourgish. The law does not guarantee access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities (radio 100.7 and RTL radio and television as it assumes a public service mission). Relating to the audiovisual sector, dominated by RTL, the programming hours dedicated to minorities are considered to be overall not proportional to the size of the population in the country. As for the radio sector, the offer is more proportional to the size of the population in the country as several radios target the linguistic minorities of the country. Relating to the print sector, the minority press, i.e. the press targeting foreign residents in Luxembourg, is considered to be rather proportionate.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores medium risk (56%). There are currently 10 local radios in Luxembourg. The law grants local radio access to media platforms under certain conditions: the local media must be run by non-profit associations, and should respect pluralism in the presentation of local news and ideas. The radio frequencies reserved for local radios are listed by the grand-ducal regulation. The Independent Luxembourgish Audiovisual Authority (ALIA) grants permissions for local and regional radio stations (art.17 and art.35.2.a) (while permissions for national radio stations are granted by the Minister of Media and Communication and ALIA only needs to be consulted). The latter is in charge of controlling the content of local and regional radios. There are however no subsidies or particular policy measures in support of local/regional media, nor are there any specific provisions granting legal recognition to community media as a distinct group (alongside commercial and public media). There is only one radio (radio ARA) that offers services largely corresponding to what one might expect from community media. Radio ARA is independent in practice and benefits from limited state subsidies for the promotion of a specific youth program.

The indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities scores high risk (75%). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was ratified in 2011. While there is no specific law implementing this convention, several action plans have been elaborated to help to achieve the objectives of the Convention by introducing targeted measures. In parallel, the Independent National Authority (ALIA) has the mission “to encourage audiovisual media service providers under its jurisdiction to ensure that their services are gradually made accessible to people with visual or hearing impairments”. It does however not have any binding power, which means that ALIA cannot impose any measure and does not have any budget for promoting such initiatives. This “soft approach” probably explains the numerous limitations. In the audiovisual sector, RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg, the dominant national TV service, includes French and German subtitles for national news of the second broadcast at 8.30pm, and a summary of the news in French called “5 minutes”. This is the only programme with subtitles and it should be said that the subtitle service is not offered in Luxembourgish. Moreover, no audio descriptions are available for the TV channels in the country.

The indicator on Access to media for women scores a medium risk (50%).The general principle of gender equality is present in article 11 of the Constitution and is specifically guaranteed in the law of May 26 2008 on the equality of treatment of men and women. A worker that considers that the law on equal treatment has not been respected can file a complaint in the labour court (tribunal du travail) or can ask for mediation solutions provided by the Centre for Equal Treatment (CET) that was created by law in 2006. The CET carries out its missions independently, and its purpose is to promote, analyse and monitor equal treatment between all people without discrimination on the basis of race, ethnic origin, sex, sexual orientation, religion or beliefs, handicap or age. The PSM (i.e. sociocultural radio) has not formulated any gender equality policy yet Out of 38 employees with a long-term contract, 16 are women and out of 9 members of the Executive Board, 3 are women

The indicator on Media literacy scores a medium risk (25%). The policy on media literacy is only nascent and policy measures are fragmented. Media literacy is present in the 2009 law on the organisation of primary school that states that media education should be integrated at different levels of the teaching and in many initiatives aiming at promoting some aspects on media literacy within and outside the formal education system. Media literacy initiatives are widespread and the director of ALIA and the person in charge of the media literacy programme at the governmental agency SCRIPT recognize the necessity to promote a more centralized, coherent and binding media literacy program in formal and non-formal education.

4. Conclusions

The report shows that the difficulties in achieving a high level of media plurality, especially in the audiovisual sector, are essentially due to two factors. First, the absence of specific media market competition law which has favoured the development of a high level of horizontal and cross-concentration and second, the very specific national linguistic and demographic reality. Ensuring media pluralism and an offer adapted to the social reality presents a challenge since almost half of the resident population does not have Luxembourgish nationality and three official languages are used. This being said, the report points to important differences among and within the media categories. More precisely, it shows that the audiovisual sector is highly dominated by one broadcaster (RTL) targeting the Luxembourgish speaking population while the radio and print sectors tend to be more diverse and better adapted to the linguistic minorities.

In terms of policy recommendations, we suggest:

1) To encourage policymakers to conduct and finance more studies on media-related issues such as the audience, market shares, the influence of political actors, and the PSM. These investigations should nurture public debate and might be initiated by civil society groups or/and the university;

2) To increase human and financial resources of the independent public authorities (ALIA) in order to guarantee a more consistent and continuous supervision.

3) That the government and parliament launch inclusive debates and consultations on the right to information as Luxembourg is one of the few countries in Europe where this fundamental right is not legally protected.

4) To launch inclusive debates and consultations on the form of “public service” required by the social reality in Luxembourg. The current renegotiation of the concession contract with CLT-UFA should be used by media, the parliament and government as an opportunity to have a thorough debate on the type of public service that is adapted to the particularities of the country.

5) Develop the media education system/policy as at the moment it is still nascent, decentralized and largely based on the goodwill of some teachers and/or institutions. More efforts are needed in order to raise and strengthen children’s, teenagers’, but also adults’ awareness concerning the use of traditional, but most of all digital and social media (i.e. critical analysis of sources and production of media, value of different opinions).

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Raphaël | Kies | Senior researcher | University of Luxembourg | X |

| Kim | Nommesch | Independent collaborator | forum asbl | |

| Céline | Schall | Postdoc | University of Luxembourg |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Romain | Kohn | Representative of media regulators

|

Independent Luxembourgish Audiovisual Authority

|

| Luc | Caregari | Representative of an association of journalists | woxx/ Syndicat des journalistes

|

| Linda | Saadaoui | Academic/NGO researcher on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | Ameddias

|

| Jean-Lou | Siweck | Representative of a media organisation | Luxemburger Wort (chief editor) |

| Jean-Claude | Franck | Representative of a broadcaster organisation | Radio 100,7 (chief editor)

|

Annexe 3: Stakeholder meeting report

Date: 2nd February 2017

List of participants:

- Claude Adam (MP, member of the Parliamentary Committee on Higher Education, Research, Media, Communication and Space)

- Diane Adehm (MP, member of the Parliamentary Committee on Higher Education, Research, Media, Communication and Space)

- Luc Caregari (journalist, President of Syndicat des journalistes)

- Céline Flammang (Adviser at the Department of Media and Communication)

- Jean-Paul Hoffmann (Director of radio 100,7)

- Romain Kohn (Director of ALIA)

- Paul Peckels (Director of Saint-Paul Group)

- Claude Wolff (Member of the Executive Board of ALIA)

- Jean-Paul Zens (Director of the Department of Media and Communication)

General Comments

Changes produced by digital technologies are not considered

Several participants highlighted that the increasing role of digital technologies in the media sector was not considered in the report. With some exceptions (cf. criteria on the access to Internet, net neutrality or freedom of expression online), the report is based almost exclusively on the analysis of traditional media although digital instruments influence the media offer and media consumption patterns. One participant pointed to the fact that a stronger consideration of this aspect could change the results related to social inclusion, programme quality and public subsidies – at least in the case of Luxembourg. In his opinion, the online linguistic offer is larger (some sites offer a Portuguese or an English online version). Yet, online information creates new risks in terms of media quality and media education that need to be taken into account. Hence, the experts considered the recommendation relating to media education as an essential step in the era of social media. In this context, the concept of information literacy also seems a more appropriated term than media literacy.

Luxembourgish particularities

The small size of the country as well as the important role of multilingualism turn Luxembourg into a specific case. These characteristics partly explain fort instance the “high risk” result for concentration of the market and also the restricted number of human resources to actively monitor media content. One of the experts found that this aspect was not sufficiently highlighted in the report. This may create a misleading picture of Luxembourg in comparison to other countries (especially bigger ones). In this context, the high consumption of foreign media also needs to be considered. Some quoted cultural specificities (pragmatism, the role of Luxembourgish language in identity building processes, historic role of RTL, special view on media) that might explain some of the results.

Applying similar criteria to different contexts

Several participants thought that applying the same evaluation criteria to all countries risked ignoring the particularities of certain countries and creating a misleading picture. The authors of this report acknowledged some procedural weaknesses, but underlined that a qualitative approach should be used while also considering the local context. Nevertheless, all agreed that the report was an important working paper offering a general view and synthesis of the situation of media in Luxembourg.

Absence of a public debate on the future of the national media sector

Several participants regretted the absence of analysis or scientific data on the situation of the media sector in Luxembourg and of a general debate on its future (in particular in relation to public service media). This is unfortunate especially considering that the concession contract is in the process of being renegotiated. It is a crucial moment indeed as the scope, the financing and the control of the public service mandate of RTL are being (re)defined (see below).

Specific Comments

Powers of ALIA and the Press Council

Several participants felt that the Independent Luxembourgish Audiovisual Authority (ALIA) did not have sufficient means to control certain licences in an efficient and permanent manner (as it is also mentioned in the report). This is the case especially for Hungarian and Dutch broadcasters due to linguistic barriers. One expert also stated that the lack of human resources did not allow the authority to actively participate in national and European networks and activities.

However, one participant also claimed that proactive control procedures did not correspond to the liberal approach of the government. The latter prefers self-control rather than interference with freedom of expression. According to this reasoning, ALIA should only exercise control when important issues arise or complaints are submitted. A debate followed between advocates of citizen empowerment and education on the one side and those in favour of more regulation (speaking time of politicians, commercial influence, respect of minorities, horizontal and cross media concentration, …) on the other side.

Furthermore, the Press Council cannot react to complaints against publications that are not recognised (such as tabloid press). Thus, it cannot react in most cases, as the majority of complaints concern tabloid press.

Media viability

One person thought “low risk” for media viability did not reflect the reality, “medium risk” or “high risk” would in his opinion be more accurate. The authors of the report suggested the results could be explained by the lack of information on revenues in the media sector (an aspect that has also be pointed to by the participants). They furthermore justified their evaluation by referring to the generous public direct and indirect subsidies in favour of the print sector. These were also questioned by the participants: the amount of indirect subsidies would be higher than that of direct subsidies and their legitimacy could be debated. However, since the amount of indirect subsidies is not public, it is difficult to certify it.

Right to information

One participant insisted on the necessity of creating a law on the right to information as Luxembourg is the only European country without such a legislation. He underlined that current provisions limited the work of journalists and encouraged politicians and civil servants to consider these as communication officers.

Public service media

One stakeholder advocated for further developing and strengthening the existing public service medium (radio 100,7). He observed that in comparison to other European countries, investment in public service was marginal and noted that radio 100,7 mainly broadcasted in Luxembourgish which did not correspond to the multilingual and multicultural reality of Luxembourgish society. Yet, in the context of the renegotiation of the concession contract between CLT-UFA and the Luxembourgish government – providing RTL with a public service mandate – the notion of public service media also concerns RTL Lëtzebuerg TV and radio.

The question of public service created a general discussion between the participants and the substantive issues were raised: To what extent commercial media can assume a public service mandate that meet the expectations in terms of quality? Does the public service broadcaster risk being dependent on advertising? Is it necessary to extend the offer in terms of programme? Whom should public service media address (who is the “general public”?)? Which language public service media should be broadcasted in?

If public service media becomes larger, financial issues emerge: How can more programmes be financed if more and more companies publish adverts online (and not in traditional media)? Should the state cover losses of a private broadcaster to allow the latter to continue producing content? Should we think public service radio and TV separately or in terms of “converged media”, maybe online? Several participants also deplored that the debate mainly concentrated on financial aspects instead on content and a new concept of public service adapted to the new realities of the country. In this context, they insisted on the necessity of organising an inclusive debate to decide on the form and the scope of national public service. Some criticisms were also issued concerning the short period (3 years) of the new concession contract currently being renegotiated with RTL as it created insecurities, most of all for the journalists working for the broadcaster.

Role of associative media

One participant insisted on the fact that associative media (such as Radio Ara) should be receive more support in the future.

Non-access to concession contracts

Several participants regretted that the concession contracts were not publically available.

Gender equality

Several participants did not agree on the issue of equal representation of women and men in media. It is however clear that male domination persists in the sector and the numbers indicated for the team composition of radio 100,7 were adjusted after the meeting (the actual proportions are lower). Some thought that a women’s quota meant that it needed to be applied to all areas including for instance the selection of interviewees. It has been replied that is not desirable to prioritize gender quota to other qualitative criteria (i.e. competence, relevance, availability).

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Source: https://minorityrights.org/country/luxembourg/

[3] Source: Statec 2016.

[4] Source: Étude TNS ILRES Plurimedia Luxembourg 2014/2015, available online (https://www.ipl.lu/wp-content/uploads/TNS-ILReS_Plurimedia_2016-II.pdf)

[5] See for example: Roland Marie-Laure, “Pourquoi un fait divers est devenu une affaire d’état”, Wort, 07.12.2016. (https://www.wort.lu/fr/culture/affaire-lunghi-rtl-bettel-pourquoi-un-fait-divers-est-devenu-une-affaire-d-etat-5849613b5061e01abe83d6fc)

[6] The details of the services established in Luxembourg can be found on Mavise https://mavise.obs.coe.int/country?id=20

[7] Neither are there legal provisions to guarantee net neutrality (although discussions are ongoing and Luxembourg strongly positioned itself in favour net neutrality).

[8] The most important distribution group is Post, a company that belongs to the state (some services have been liberalised in recent years).

[9] The chairman has resigned recently but at the moment of finishing this report, the name of the new Chairman was not public yet.

[10] This consultative commission was created by a decree of the Governing Council of 25 July 2003.