Download the report in .pdf

English

Author: Elda Brogi[1]

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM, carried out in 2016. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey, with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The research was based on a standardized questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection for Italy was carried out centrally by the CMPF team.

To ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annex 2 for the list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support for the media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0 to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97%, by default, to avoid an assessment of either a total absence or a total certainty of risk[2].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the EC.

2. Introduction

Italy covers an area of 301.338-km² South of the Alps and along the Mediterranean Sea. It has a population of 62,007,540 inhabitants (July, 2016, est.). [3].

Italian is the most spoken language. According to the Italian Constitution, the Republic guarantees, through specific laws, the linguistic minorities (Art. 6). Since the ‘90s, Italy has been facing a rise in the flow of immigrants from EU Central Eastern countries (Romania), from South Eastern Europe (Albania), and Northern Africa[4]. Being close to Africa, and because of its extended coastline, Italy has become the entry point for many refugees and migrants from Africa and the Middle East. As of 2016, according to ISTAT data[5], around 5 million residents are foreigners. They represent 8.3 % of the total population of the country. The most relevant groups of residents are Romanians, Albanians, Moroccans, Chinese, and Ukrainians.

Italy is the third largest economy in the Euro area, but it has been heavily hit by the recent economic crisis. In addition to this, the country has to deal with a high public debt and some structural deficiencies that hinder growth, e.g., political instability, corruption, labour market inefficiencies, unemployment, tax evasion.

There are three main parties competing for government of the Country: the Democratic Party (which is currently in power, thanks to a heterogeneous coalition with other small political parties), the right-wing party that still refers to Berlusconi’s leadership, and the Five Star Movement. The role of Silvio Berlusconi (the well-known Italian media tycoon) in the Italian political arena has decreased in the last few years since he was convicted of tax fraud and is thus forbidden to be a political candidate in elections[6].

The Five-Star Movement is the political actor that now most characterizes the Italian political landscape. The Movement was created as the initiative of a comedian, Beppe Grillo, who used his personal blog as a tool with which to gather and organize the political participation of his followers. The Movement has been gaining credibility amongst the electorate in the last few years, and it has established itself as the second main political force in the country, aiming to win the next national general election. Apart from being a new and strong actor in the Italian political landscape, the Five Star Movement is also a peculiar and unique example of a strategic use of the web as a political platform and as a tool for political communication.

The Italian media environment suffers due to market concentration and the economic crisis, but it is relatively vibrant. In terms of consumption, the audiovisual media are the main source of information in the country, while newspaper readership is declining, vis à vis a growing consumption of news online[7]. Media policy, in the last two years, has been characterized by the quite active role of the centre-left government of Matteo Renzi (Democratic Party). Renzi has been ruling with the support of a coalition that gathers together the Democratic Party and other small centrist parties. He resigned after the results of the 2016 Constitutional Referendum rejected the revision of some parts of the 1948 Italian Constitution. The Government of Matteo Renzi has promoted reforms that have affected the media sector. To mention just some of these: the reform of the governance of Public Service Media (PSM), the reform of the law on freedom of information and the introduction of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the reform of press public funding, and the introduction of a “fund for pluralism”. Some reforms, like the one that aims to cancel detention for the crime of defamation, or to reform the law on conflict of interest, are still in the pipeline in Parliament.

The Italian media market has recently been facing important changes. In 2016, Urbano Cairo (Cairo Communication), a publisher who is already active in the TV sector, gained control of the RCS MediaGroup S.p.A., the holding that owns the most read Italian newspaper, Il Corriere della Sera. La Repubblica and La Stampa, the second and third most read papers in the country now belong to the same group, L’Espresso.

In March, 2016, the Italian Competition Authority approved, upon the fulfilment of some conditions, the acquisition of RCS books by Mondadori, the main publishing house in Italy, which is controlled by the Fininvest group (Berlusconi). The audiovisual sector has been facing some major changes too: the French company, Vivendi, which is already the owner of Telecom Italia, is trying to gain control over Mediaset, one of the biggest players in the Italian audiovisual market.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

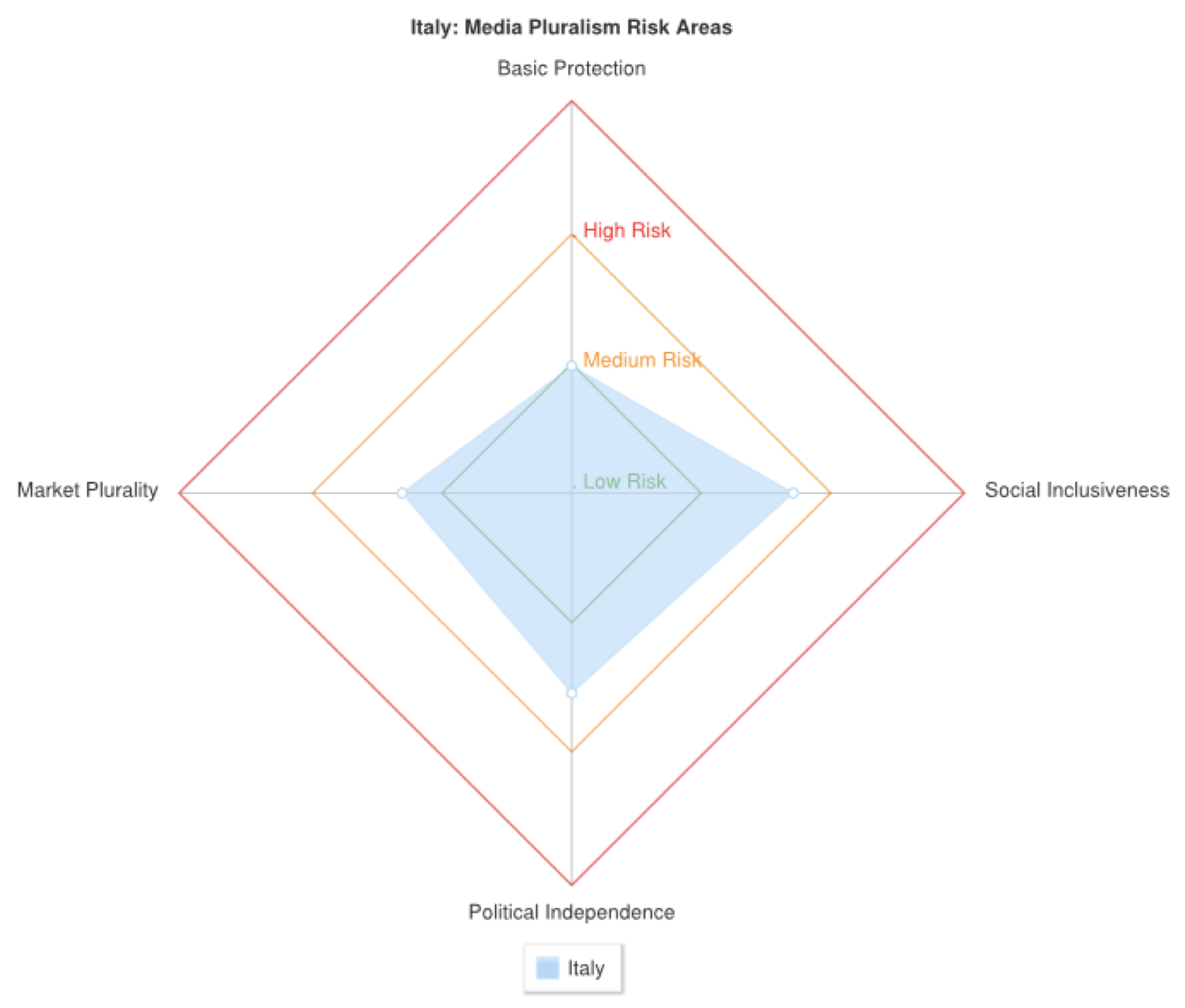

The application of the MPM2016 showed that media pluralism in Italy is at low risk in the area of Basic Protection, and at medium risk in all of the three remaining areas of investigation. Overall, seven indicators are at low risk, nine are at medium risk, and four are at high risk. High scores are reported in the Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness areas. As regards Political Independence, risks for media pluralism come from political control over media outlets and a lack of independence in PSM governance. In the Social Inclusiveness area, risks for media pluralism come from insufficient media literacy. It must be noted that, within the Market Plurality area, media ownership concentration scores 60%, a percentage that defines a medium/high risk. Risks originating from a lack of ownership transparency vis à vis the general public, are high too. Within the Basic area, the indicator that describes the status of journalists and the standards of the profession is alarmingly high for a Basic Protection indicator: Italian journalism is facing crises in terms of working conditions, professionalization, autonomy, independence and safety.

The picture that arises from the MPM2016 confirms the Italian media system is characterized by high political parallelism (Hallin and Mancini, 2004), media concentration, although this is reduced in comparison with the recent past. The analysis of the MPM2016 shows that new problems are emerging, such as a lack of media literacy, both in terms of individual digital skills and of state policies to boost critical use of the media, and of online media in particular.

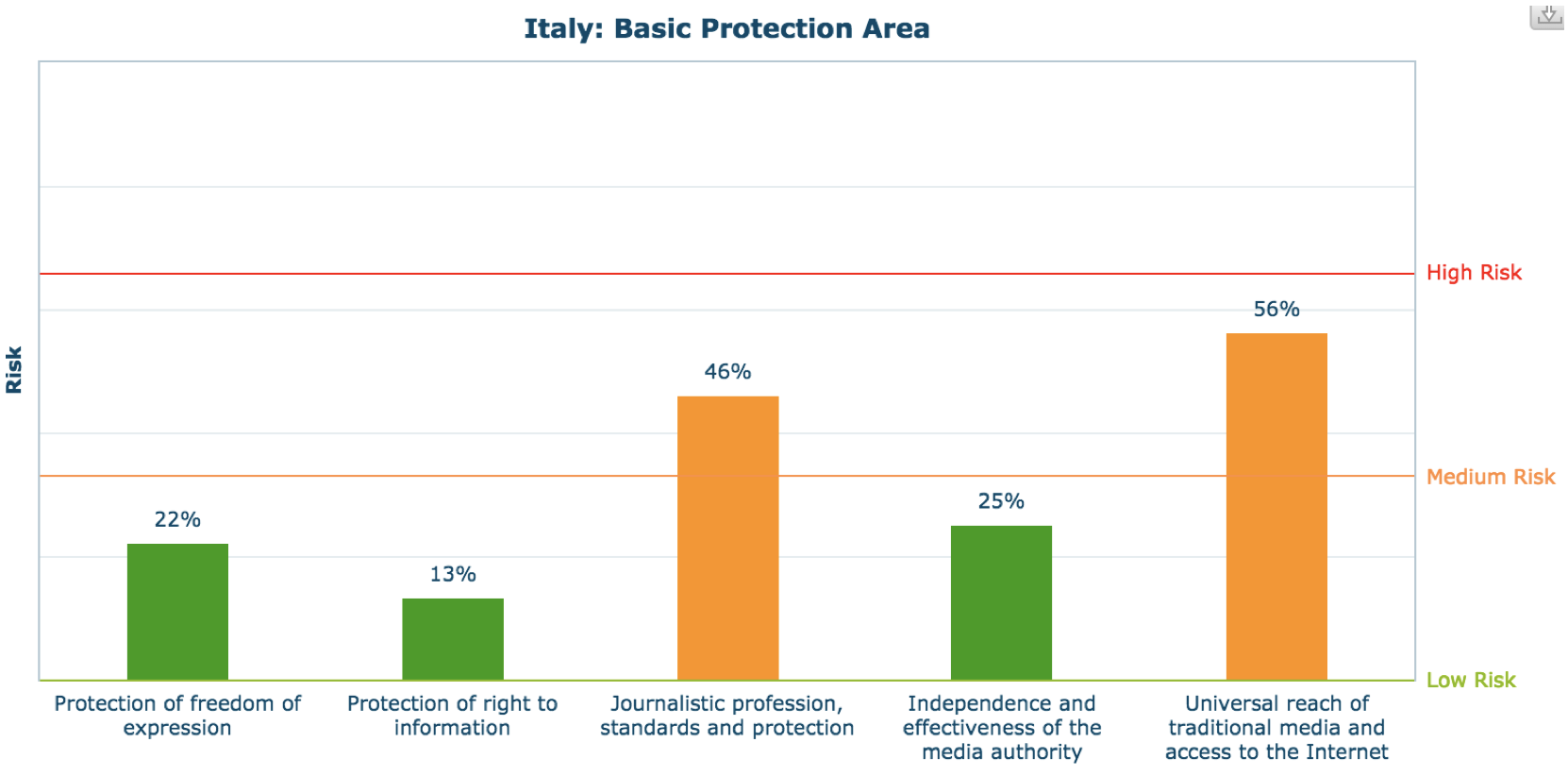

3.1 Basic Protection (32% risk – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Within the area of Basic Protection, three indicators score low risk for Italy (Protection of the freedom of expression, the protection of rights to information, and the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority), while two score medium risk (Journalistic profession, standards and protection, and the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet). Overall, the area receives a score that is still within the low risk band (32%), but that is alarmingly close to the medium one.

The Italian legal framework on the protection of freedom of expression (22%, low risk) is generally in line with international standards and the rule of Law. Art. 21 of the Italian Constitution, which protects freedom of expression, limiting it just for the sake of public (sexual) morality (Art. 21 Par. 6). Restrictive measures to protect dignity, privacy, public and private secrets are prescribed by laws. The rule of law for the freedom of expression online is generally respected too. Nonetheless, some articles of the criminal code do not fully comply with international standards and Art 10 European Convention on Human Rights: in particular, the defamation of another person (Art. 595) is a criminal offence that is punishable by imprisonment, which cannot be considered a proportionate sanction for defamation. The criminalization of defamation poses some risks for journalists’ freedom of expression, and it creates a “chilling effect” that can be detrimental for the effective and free exercise of journalistic activity[8]. The Italian Parliament has been discussing a reform of the law on defamation, aiming to repeal imprisonment as a punishment for defamation, but the Bill has not yet been approved. The crime of insults against the honour and decorum of others (Art. 594 of the Criminal Code) was, instead, repealed in early 2016 [9].

Protection of the right to information scores a risk of 13%: the low risk for this indicator is an improvement over the assessment on the same indicator under MPM2014 (medium risk) (CMPF, 2015). The decreased risk is due to a better score in terms of the existence and effective implementation of a law on the freedom of information. In 2016, the Government approved a legislative decree on transparency (D.lgs n. 97/2016) that details the “transparency” reform which had already been started in 2013 (see MPM2014). This aims to combat corruption in the Public Administration. The 2016 decree empowers citizens with access to the data and documents of the Public Administration relevant to public and private interests (“civic access”). Any refusals by the Administration to provide data must be duly motivated and may be subject to the scrutiny of an official who is responsible for the prevention of corruption and for transparency within the administration.

The indicator on the Journalistic profession, standards and protection, scores medium risk (46%). The indicator takes into consideration many different variables that depict the condition of journalists in a given country, in terms of access to the profession, professional standards, threats and legal safeguards. The picture described by the MPM for Italy is not particularly reassuring: unlike most of the EU countries, access to the profession is not totally free (enrolment in the Ordine dei Giornalisti is required to qualify as a professional journalist); the working conditions of Italian journalists are becoming increasingly precarious and poor, while the average salary is decreasing [10]; journalists occasionally face threats and intimidation (this chilling effect coming from complaints in regard to defamation; physical threats, and threats to digital safety[11]). According to data from Ossigeno per l’informazione, 412 journalists were the victims of threats in 2016[12].

The independence and effectiveness of the media authority scores 25% risk (low risk). The law defines appointments’ procedures to safeguard the independence and efficiency of the media authority, namely, the Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni (AGCOM): in practice the nominations and appointments are made by major political parties. The fact that the President and the Board of the authority are appointed by political bodies raises the problem of actual independence from politics. This may lead to decisions that are not fully independent from political influence. However, over the past two years (the timeframe of the MPM assessment) there have been no blatant cases or evidence to prove a lack of independence in AGCOM’s decisions affecting the mass media sector. Nonetheless, when this report was written, AGCOM had not completed an evaluation of the levels of concentration in the audiovisual media market, which was started in 2015: AGCOM has suspended it in order to allow the media market to stabilise after the recent acquisitions and mergers[13].

Low average Internet connection speed, low broadband subscription rates and high ownership concentration among Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in the market contribute to the raising of the score for the indicator on the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet (56%, medium risk).

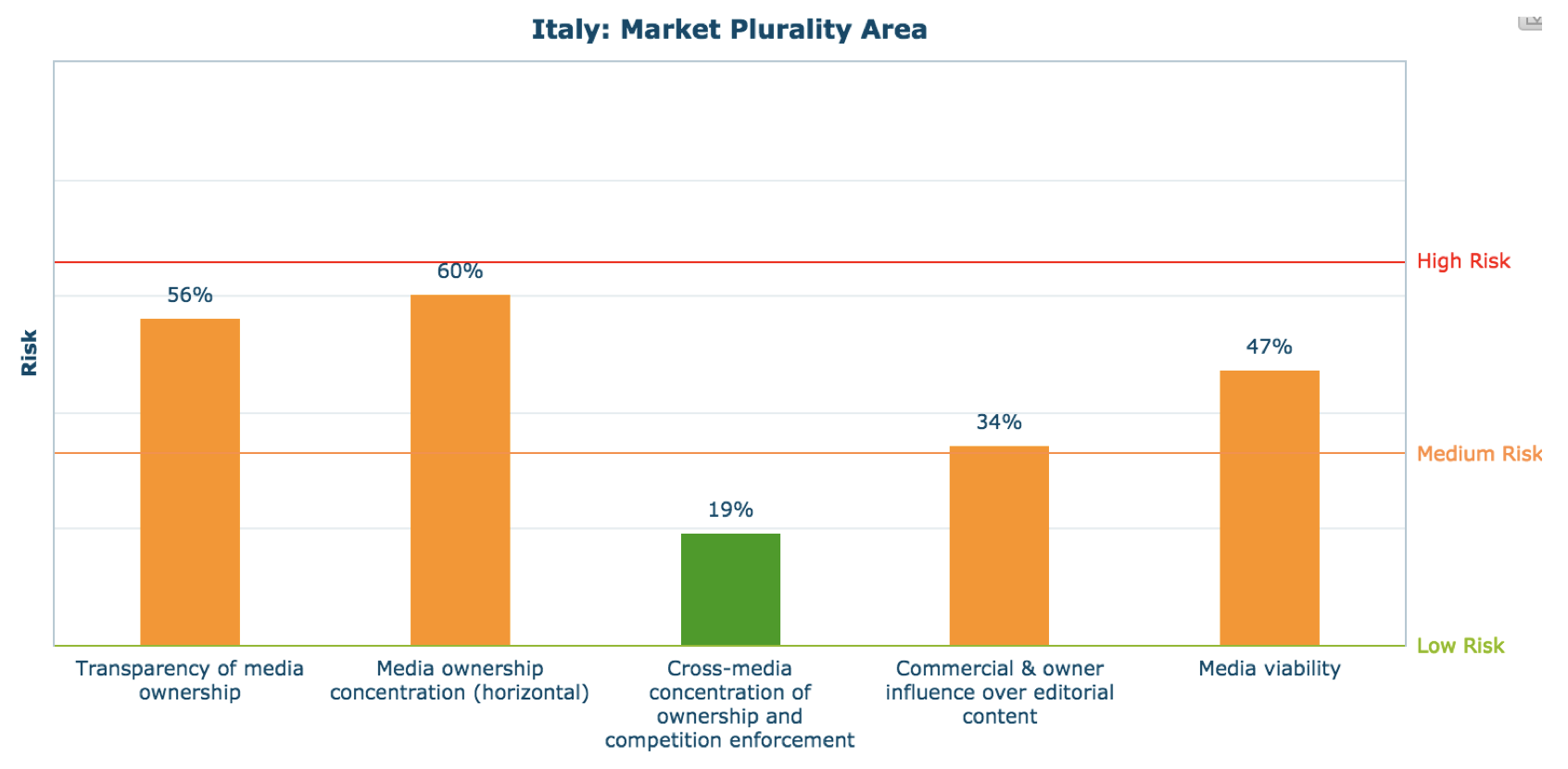

3.2 Market Plurality (43% risk – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

In relation to the ownership of media companies, the Italian media market is partially transparent: complying to the law (l.249/97) and the AGCOM rules (666/08/CONS), AGCOM collects information on the ownership structure of media companies. The Authority keeps a register of the companies that are part of the SIC (Sistema integrato delle comunicazioni / Integrated System of Communications), which includes a wide range of operators in the media and electronic communication sector, including advertising and Internet companies. No similar obligation exists vis à vis the general public, as a guarantee of transparency. In considering this last element, the indicator on the Transparency of media ownership scores a medium risk (56%).

A low level of plurality has affected the Italian media market for the last thirty years: concentration of the audiovisual market is in few hands, combined with the political ownership of one of the main media companies and the parallelism of the PSM with political powers have been a peculiarity of the Italian media system. As already mentioned, the media market in Italy has recently faced some changes, which originate both from technological developments and from the rise of new companies in the media sector. Although the digital terrestrial audiovisual market is still dominated by the two main operators in Italy (RAI [the PSM] and Mediaset), the switch over to digital terrestrial television and the increase in pay-tv and on-demand audiovisual services have challenged the rigid duopoly of the Italian audiovisual media market. In particular, at least in terms of revenues, SKY Italia has established itself as the third main component of the Italian audiovisual market (32.5% of the resources in 2015), overtaking RAI (27.8%) and Mediaset (28.4%) (See data of AGCOM, 2016). Nonetheless, the market is still highly concentrated. The regulatory framework calls for the Authority both to monitor that a media operator does not exceed 20% of the revenues of the SIC (Sistema integrato delle comunicazioni, see above) and to check whether an operator is exceeding a dominant position within a given media market. While the first threshold (20% of the SIC) has always been perceived by scholars as being too loose, as the SIC covers a very large market, the second has never been effectively implemented. In particular, the Authority has currently suspended the analysis of the relevant markets, waiting for the final definition of the Vivendi-Mediaset operation. The radio market is not as highly concentrated as the audiovisual one. The newspaper market, as mentioned, is facing some important challenges: Itedi, the publisher of La Stampa (Italy’s third largest newspaper) merged with The Gruppo L’Espresso, publisher of La Repubblica (the second largest newspaper). The operation, under scrutiny by the Italian Competition Authority for some of its implications in the advertising market at the local level[14], has established Gruppo L’Espresso as the biggest in Italy, in terms of revenues. The merger will raise the C4 ratio for the newspaper market from 54 to 60 (revenues) and from 58.7 to 64.5 (readership), still in the medium risk band, according to the MPM methodology. The general risk for the indicator on horizontal media ownership concentration is medium (60%).

The indicator on cross media ownership scores an overall low risk (19%). However, the indicator entails one sub-indicator on the existence and effectiveness of a regulatory framework that may prevent cross-ownership concentration: this sub-indicator scores medium risk (54%), as the regulatory framework has proven to be partially ineffective. The regulatory framework, in this regard, sets a threshold of 20% of the SIC market for the SIC operators: the rule is ineffective in limiting cross-media ownership, due to the wide scope of the SIC market. Specific cross-ownership thresholds, as the one limiting the newspaper ownership to those audiovisual operators who represent more than 8% of SIC, have been either circumvented in the past, or do not apply to recent cases (like RCS/Cairo Communication, as Cairo Communication’ s La7 does not reach 8% of SIC).

The law that forbids a telecoms operator from owning more than 40% of the telecoms market, to earn more than 10% of the revenues of the SIC, may prove effective in hindering Vivendi from gaining control of Mediaset[15].

The score of the indicator is lowered by the good scores for the variables on competition enforcement, and by the existence and implementation of regulatory safeguards ensuring that State funds granted to PSM do not exceed what is necessary to provide a public service.

The indicator on Commercial and owner influence over editorial content scores medium risk (34%): journalists can rely on some mechanisms in the general agreement granting social protection in the case of changes in ownership or editorial line; advertorials are not permitted. However, the structure of the Italian publishing industry does not guarantee an environment with full autonomy and independence for journalism: the major investors in the media industry are mostly entrepreneurs in production fields other than media and they are very often linked (sometimes in a non-transparent way) with political parties.

Media viability scores medium risk (47%). The media market suffers both from the general economic crisis and the disruption arising from online media. Interestingly enough, radio revenues and, of course, online advertising ones, are increasing. Recently, the Parliament passed a law on publishing that aims to reform the support system for the media, establishing a “fund for pluralism and innovation”.

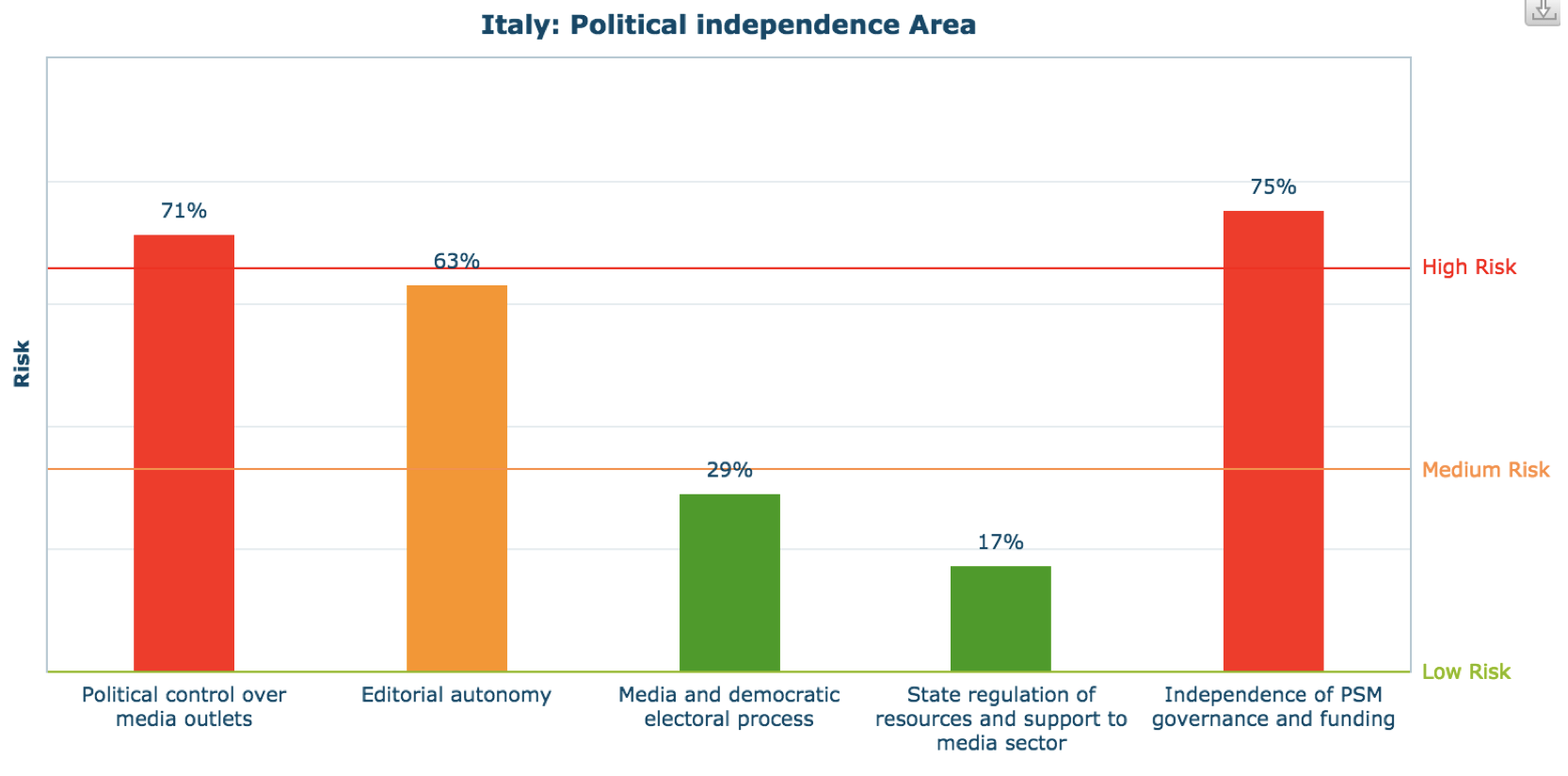

3.3 Political Independence (51% risk – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The level of political influence on the media in Italy is very high. The relationship between political (and economic) powers and information and the media can sometimes be very close. Nonetheless, it is difficult to clearly define whether a given media outlet is influenced by politicians, or whether it is voluntarily part of the political game. This is apart from the cases where politicians are blatantly the owners, or clearly control the ownership, of a given media outlet, there are cases of newspapers acting almost as political parties or, at least, supporting a political party while not being a party-press[16].

It is not, therefore, surprising, that the indicator on political control over media outlets scores high risk (71%), and the one on Editorial autonomy scores medium risk, with 63% pointing to higher risks. The regulatory framework lacks an effective law on the conflict of interest: the Frattini law was criticised by the Venice Commission[17] and the reform of this matter is still pending in the Parliament. Editors in chief have been replaced, in some cases, as a result of alleged political pressures.

The indicator on media and democratic electoral process scores low risk (29%). The low score (although it is a high percentage within the low risk band) is due to the composition of the indicator, as it deals mostly with PSM coverage during the electoral period. The Italian legal framework contains a specific rule on the fair distribution of airtime to political parties and candidates during the electoral period (l.28/2000). Data provided by AGCOM show a relatively fair system for the allocation of airtime in RAI during the recent campaign on the constitutional referendum[18]. The main element of risk has been related to the over-representation of the Prime Minister on PSM (and on commercial channels, too).

The indicator on the State regulation of resources and support for the media sector scores low risk (17%): the Italian scenario for radio and television has changed after the switch to digital terrestrial broadcasting. Although the transition to digital has been complicated and it has consisted of a sort of projection of the existing duopoly in analogue broadcasting, the linear AVMS offer is now open to a higher number of operators. While, in the last decade, Italy has been struggling with the transition to DTT, the main debate today is concentrated on how to make the 700 band available for mobile telephony, in line with the EU strategy. Major broadcasters are hindering this policy and trying to postpone this conversion, at least until 2022[19]. In terms of support for the media sector, public subsidies, in general, relate to newspapers and local audiovisual media (details in Sileoni and Vigevani, (2016)). The public funding mechanisms have been heavily criticized in the past, as it mostly benefitted the party press. The new law n198/206 (Institution of a Fund for Pluralism) abolishes public funding for the political party press and for unions and seeks to benefit “pure” publishers, who do not have other interests in other commercial fields.

The independence of PSM governance and funding scores a high risk (75%): the Board of the PSM, RAI, currently includes 9 members who were appointed entirely for their politics: 7 members were appointed by a Parliamentary committee overseeing the PSM’s activities (Commissione parlamentare per l’indirizzo generale e la vigilanza dei servizi radiotelevisivi”) and 2 members were appointed by the Ministry of the Economy, the main shareholder in the company. The President was appointed from amongst the latter two. It must be noticed that the appointment procedures for the Board of Administration of RAI were reformed in 2015 (7 members, 4 appointed by the parliamentary commission, 1 by the employees of RAI, two by the government): the reform is not considered an effective shift to a governance system independent of politics (Grandinetti, 2016). One of the recent reforms that has affected Italian PSM is related to the collection of the license fee, which is now paid with the electricity bill. This procedure has proved to be effective as, according to recent data, the revenue from the license fee collection was higher in 2016 than in the past[20].

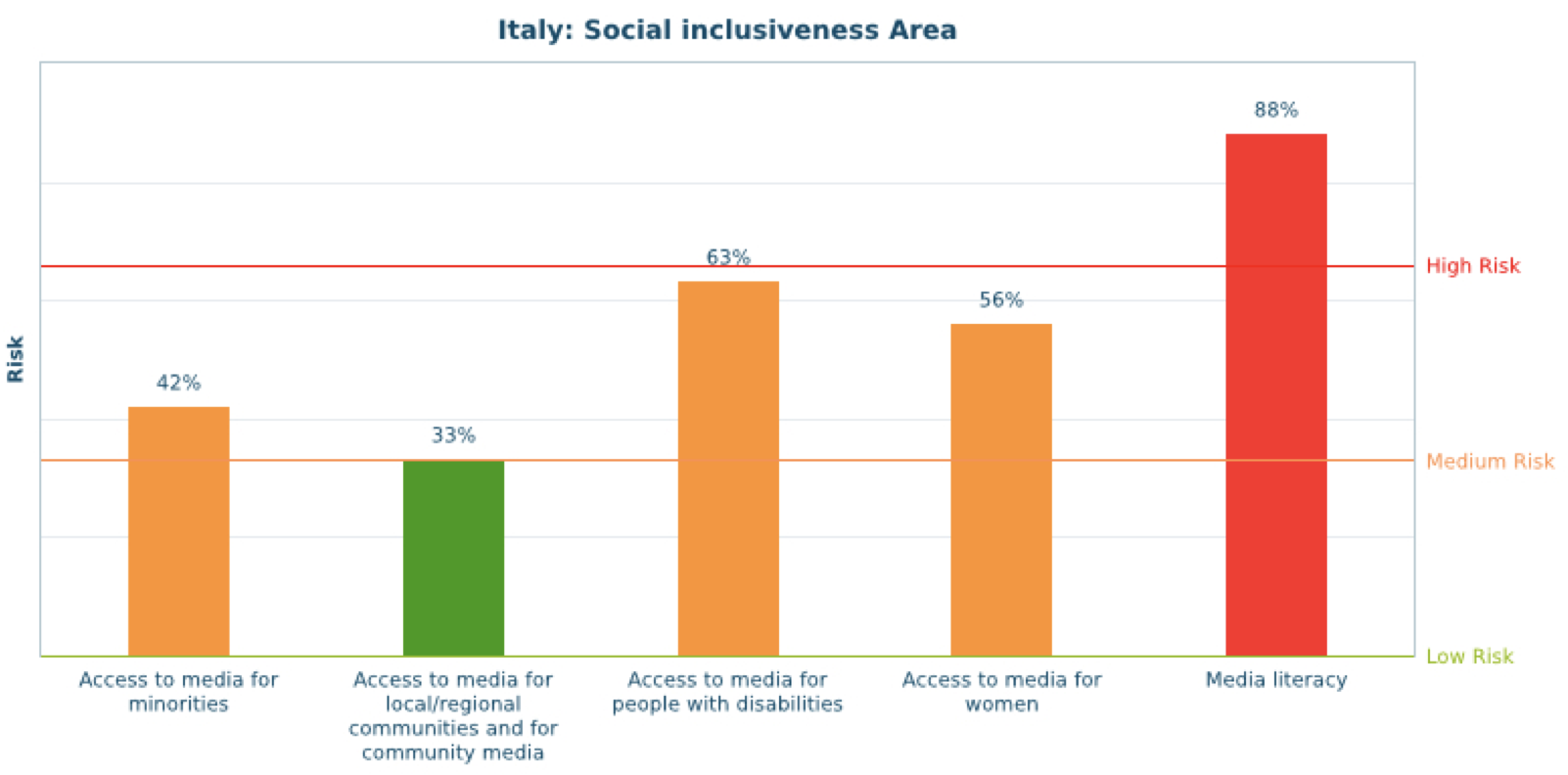

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (56% risk – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Social Inclusiveness is the area that scores the highest risk in Italy. Media literacy (88%) is the indicator that scores the highest in the MPM for Italy.

The indicator on the Access to media for minorities is at medium risk (42%): the Italian media landscape is characterized by a very high number of TV and local radio stations, which provide viewers with a relatively wide variety of content that targets minorities too. RAI has a specific role in assuring that minorities are included in its offer: according to the latest corporate report (“Bilancio sociale”), RAI has dedicated a significant number of hours to TV and radio programs in German, Slovenian, Ladin and French.[21] Fewer programs are available for other minorities who do not qualify as historical language minorities.

Local media are safeguarded by Legislative Decree 177/2005, which reserves one third of the network capacity for them. The law recognizes also the existence of community media, but does not contain any specific provision that grants them either independence or access to platforms. RAI has a specific role and mission to have local branches and to locally broadcast news and programs in minority languages.

Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk (63%). Art.32, Par.6 of the D.lgs 177/2005, states that AVMS providers have to adopt adequate measures to protect such users. The RAI Service Contract (Agreement with the Ministry of the Economy) sets stricter rules for PSM: according to Art. 13 of the latest version of the Contract, RAI is requested to provide subtitles to at least 70% of the airtime in generalist channels, from 6 a.m. to 12 p.m, and to provide subtitles and translation in ISL (Italian Sign language) for at least one bulletin per day on the 3 main channels. However, as per the audio descriptions, the Contract generically asks Rai to increase its offer of audio described programming, without imposing any quantitative threshold or deadline. AGCOM is currently working with Confindustria on a code of conduct that will provide a set of measures allowing users with disabilities to access the media[22].

The medium score for Access to media for women (56%) comes from the low shares of women as both subjects and sources in news, and this covers newspapers, radio and television news, of women as subjects and sources in Internet news websites and news media tweets, and from the low ratio of women among news reporters[23]. According to Law 120/2011, at least a third of the members of the executive board of public companies should be women. Although the Italian PSM, RAI, seems willing to introduce “female quotas”, women now make up less than a third of the members of RAI’s Executive Board.

Finally, the indicator on Media literacy is the one that scores the highest in the MPM2016 with 88% (high risk). There are no legal documents framing Media Education/Media Literacy policies, and there no clear authority that oversees Media Education initiatives in Italy. National policies deal mostly with the promotion of digital literacy, which focuses on the incorporation of technologies into the learning environment. The absence of institutional coordination on Media Education practices has motivated civil society to come up with the Carta di Bellaria[24], an agreement made in April, 2002, by a large group of political representatives, educators and broadcasters with the aim of regulating the criteria, practices, qualitative parameters, ethical principles and legal frameworks of Media Education projects and products. This is not a binding agreement and has no legal foundation, however, it can be considered the first official act that has given recognition to all the institutional and non-institutional subjects that are actively involved in Media Education projects and it has provided them with a coordinated framework of organizational standards and general aims for their work (Aroldi, Murru, 2014). Media literacy is absent from the compulsory education curriculum. In 2007, the Italian Ministry of Education launched a National Plan for Digital Schools (Piano Nazionale Scuola Digitale) to mainstream Information Communication Technology (ICT) in Italian classrooms and to use technology as a catalyst for innovation in Italian education, that will hopefully be conducive to new teaching practices, new models of school organization, new products and tools that can support quality teaching[25].

The indicator score also takes into account the percentage of the population that has at least basic digital usage skills (55%) and, within this, the percentage of the population that has at least basic digital communication skills (63%). These are values that are still below the EU median (77%).

4. Conclusions

Italy has been at center stage on issues that are related to media pluralism for the last two or three decades. Technological development in the media sector has helped to boost market plurality; recent reforms have reinforced the basic prerequisites for an enabling environment for journalists (for instance, the new freedom of information law); the new law that establishes a fund for pluralism of information and innovation has created high expectations for the fairer distribution of state resources to newspapers and local broadcasting (Sileoni and Vigevani, 2016. Although some elements point to positive developments for pluralism in the Italian media landscape, the assessment of the MPM2016 still shows several spheres for concern in the four main areas of analysis. MPM2016 confirms some negative trends that had already been picked up by MPM2014 (CMPF, 2015).

As already mentioned, above, the standards of the journalistic profession are becoming poorer in terms of professionalism and working conditions. This is a trend that is particularly negative in Italy, and MPM2016 confirms the findings of MPM2014. Nonetheless, it must be stressed that Italy can rely on initiatives (like LSDI[26] and Ossigeno per l’ informazione[27]) that actively monitor journalists’ working conditions and threats to journalists, allowing an informed debate on this alarming situation. As regards Basic Protection, while the crime of insult has been repealed, the draft law on the reform of the crime of defamation has been pending in Parliament for years. The final Parliamentary vote on this draft could be a further step towards a legal framework that is more consistent with international standards.

Another reform that is pending in Parliament is on conflict of interest: the latter is a problem in Italy, since many political and economic interests are still intertwined.

Recent changes in the ownership of some media outlets may also affect media pluralism in the country (Gruppo L’ Espresso/Itedi), in the short term at a local level, considering the mostly local circulation of La Stampa. As regards the Cairo Communication/RCS operation, considering La7 has a small percentage of the SIC and a small audience, no imminent dangers for media pluralism can be envisaged. .

PSM’s parallelism with politics has probably not been solved by the recent reform of RAI governance. In this regard, the Parliament and the Government should propose reforms, aiming to create a PSM that is really independent from politics. This is particularly important in this age of “post-truth”, where the political debate is heavily marked by online political communication.

A very important step forward should be made as regards media literacy: the existing, very limited, policies are not tackling the problem of the lack of basic digital skills and a critical understanding from media users, while a strong investment in media literacy should be fundamental to really empowering the citizens. This result, in line with the similar result obtained during the MPM2014 implementation, constitutes an alarming trend that should be seriously, and as soon as possible, tackled by the institutions. The population’s level of media literacy dramatically affects effective pluralism, especially in the online environment; a lack of media education for the younger generations could really affect media pluralism and democracy in the near future. Again, strong policies on media literacy become basic conditions for media pluralism in a political landscape, like the Italian one, where one of the main political parties is a movement that was born as an online platform.

References

Aroldi, P., Murru, M.F. (2014) Media and Information Literacy Policies in Italy (2013), , available at https://ppemi.ens-cachan.fr/data/media/colloque140528/rapports/ITALY_2014.pdf (last access, 20 march 2017)

AGCOM, (2016), Relazione annuale 2016 sull’ attività svolta e sui programmi di lavoro available at https://www.agcom.it/relazioni-annuali

Casarosa, F. and Brogi, E. (2011), Does media policy promote media freedom and independence? The case of Italy, https://www.mediadem.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Italy.pdf

CMPF, (2015) Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe – Testing and Implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2014 available athttps://hdl.handle.net/1814/38886

CMPF, (2016) Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe – Testing and Implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2015, available at https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/40864

Grandinetti, O., (2016), La governance della RAI e la riforma del 2015, Rivista trimestrale di Diritto pubblico, 2016, 3, pp 833-873

Hallin, D.C. and Mancini, P. (2004) Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics , Cambridge University Press

Sileoni, S., Vigevani, G.E., (2016) Media Pluralism in Italy, in Bard, P., Bayer, J., Carrera, S., A comparative analysis of media freedom and pluralism in the EU Member States, 2016 available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/571376/IPOL_STU(2016)571376_EN.pdf PE571376

Rea, P. (ed), Rapporto LSDI sul giornalismo in Italia. La professione giornalistica in Italia (aggiornamento 2015), LSDI available at https://www.lsdi.it/2017/giornalismo-italia-il-nuovo-rapporto-di-lsdi/

Annexe 1. Country Team

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Elda | Brogi | Scientific Coordinator | CMPF | |

| Davide | Morisi | Research Associate (until December 2016) | CMPF | |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Gennaro | Carotenuto | Researcher | Università di Macerata |

| Benedetta | Liberatore | Director (audiovisual content) | AGCOM |

| Giovanni | Gangemi | Official | AGCOM |

| Sergio | Splendore | Researcher | Università di Milano |

| Giulio Enea | Vigevani | Professor | Università di Milano Bicocca |

| Vittorio | Pasteris | Journalist | Member of LSDI |

| Giulia | Ottaviani | FIEG |

—

[1] Davide Morisi (CMPF) collaborated in the data collection.

[2] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[3] CIA Fact Sheet-Italy https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_it.html

[4] As of beginning of 2016, Morocco (510.450), Albania (482.959), China (333.986), Ukraine (240.141) e India (169.394). Data: ISTAT https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/190676

[5] https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/180494

[6] Berlusconi has appealed to the Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, as he claims this interdict is illegal, since this sanction was inflicted under a law that was passed after the crime that he was condemned for was committed.

[7] Reuters, Digital News Report 2016, https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2016/italy-2016/#fnref-4051-2

[8] Ossigeno per l’informazione, (2016) Taci o ti querelo! Gli effetti delle leggi sulla diffamazione a mezzo stampa in Italia Ogni anno 6813 procedimenti, 155 condanne, 100 anni di carcere https://notiziario.ossigeno.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/DOSSIER_TACI_O_TI_QUERELO.pdf

[9] Dlgs 15 gennaio 2016, n. 7 Disposizioni in materia di abrogazione di reati e introduzione di illeciti con sanzioni pecuniarie civili, a norma dell’articolo 2, comma 3, della legge 28 aprile 2014, n. 67 (GU n.17 del 22-1-2016)

[10] Rea, P. (ed), Rapporto LSDI sul giornalismo in Italia. La professione giornalistica in Italia (aggiornamento 2015), LSDI https://www.lsdi.it/2017/giornalismo-italia-il-nuovo-rapporto-di-lsdi/

[11] For a detailed analysis of threats to journalists, see the reports of Ossigeno per l’ Informazione https://www.ossigenoinformazione.it/

[12] https://notiziario.ossigeno.info/tutti-i-numeri-delle-minacce/dati-aggregati-tavola-3/

[13] https://www.agcom.it/documents/10179/6758530/Comunicato+stampa+31-01-2017/8e82b33b-3010-488b-9e92-51ecf81f9f02?version=1.0.

[14] Pending the publication of this report, AGCM approved the merger, with conditions case, https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/topnews/2017/03/09/antitrustok-condizionato-espresso-itedi_aea1c725-5017-461d-9245-5bcad920b72a.html. Moreover, AGCOM has acknowledged that the merger does not breach the specific anti-concentration rules of the press market (l.416/81) https://www.agcom.it/documents/10179/7677581/Documento+generico+08-05-2017/b16391ea-7499-4de7-a59d-9ced9052921e?version=1.0

[15] Pending the publication of this report, AGCOM has acknowledged that Vivendi is violating the law Del. 178/17/CONS https://www.agcom.it/documents/10179/7421815/Delibera+178-17-CONS/bb20ae9f-21eb-4d39-baf9-ee3fc9d8737a?version=1.0

[16] This is a confirmed trend. See Casarosa, F. and Brogi, E. Does media policy promote media freedom and independence? The case of Italy, https://www.mediadem.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Italy.pdf , p.46.

[17] European Commission for Democracy through Law, Opinion on the compatibility of the laws “Gasparri” and “Frattini” of Italy with the Council of Europe standards in the field of freedom of expression and pluralism of the media, Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 63rd Plenary Session (Venice, 10-11 June 2005) https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2005)017-e

[18] https://www.agcom.it/risultati?q=par%20condicio%20referendum%20costituzionale

[19] https://confindustriaradiotv.it/frequenzeil-governo-chiedera-alla-commissione-europa-rilasciare-la-banda-700-alle-tlc-non-del-2022/

[20] https://www.corriere.it/economia/17_febbraio_09/gettito-record-il-fisco-2016-incassati-oltre-450-miliardi-euro-38dec0e8-eeae-11e6-b691-ec49635e90c8.shtml

[21] See https://www.bilanciosociale.rai.it/it/l-attenzione-offerta-radiotelevisiva-specifici-temi).

[22] Information provided by Benedetta Liberatore and Giovanni Gangemi, AGCOM, members of the MPM group of experts for Italy (see Annexe 2).

[23] Secondary data from the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP). The Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) is the world’s longest running and most extensive research on gender in the news media (since 1995), 2015. https://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/regional/Europe.pdf

[24] https://www.mediaeducationmed.it/documenti-pdf/documenti-ufficiali/doc_view/8-20020413-carta-di-bellaria.html

[25] This indicator has been assessed based on the input of Sara Gabai Sukhothai Thammathirat of the Open University, Thailand. Her contribution has been reported almost verbatim. CMPF thanks Sara Gabai for the precious information she has provided.

[26] https://www.lsdi.it/

[27] https://www.ossigenoinformazione.it/