Download the report in .pdf

English – Greek

Author: Christophoros Christophorou, Lia-Paschalia Spyridou

December, 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Cyprus, the CMPF partnered with Christophoros Christophorou, who conducted the data collection, scored and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Cyprus team organized a stakeholder meeting, on 2 December 2016, in Nicosia. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction[2]

Cyprus has an area of 9,251 km2 with a de jure population of 847,000 (2014), of whom 152,000 are non-Cypriots. The official languages are Greek and Turkish.

The 1960 constitution of Cyprus recognises two power-sharing communities, the Greek and the Turkish communities. Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots live segregated since the collapse of the bi-communality (1964) and the summer 1974 Turkish Army invasion that divided the island. The invasion followed a coup by the Greek Junta in Athens against President Makarios. Armenians, Maronites and Latins are recognised as religious groups that ‘joined’ the Greek community. They total about 7,500 persons. EU and non-EU foreign citizens living in Cyprus represented 11.2% and 8,4% of the employed labour respectively (2016). Greek Cypriots dominate the power, society and cultural life.

The Republic is currently undergoing a post-memorandum surveillance period under the European Stability Mechanism, since it exited a bailout program in March 2016. The aid programme agreement was signed in March 2013 as a result of a serious economic crisis that excluded Cyprus from the markets since 2011. Despite the crisis, the EU Commission and the ECB expect the growth rate in Cyprus to exceed 2.5% in 2016.

A strong left-right cleavage has dominated political life since the 1940s. This polarisation has shown signs of weakening recently, while the political alienation of citizens is on the rise. Young voters fail to register, while abstention rates reached 33% in 2016. A polarising effect and coverage bias are also observed in political debates, the news and current affairs programmes. This is the result of diverging views on the Cyprus Problem and the termination of the island’s division.

The media landscape in 2016[3] featured two notable developments, namely shifts in consumption towards online media and the operation of a new TV channel. The total readership of the dailies declined to 14.1% from 19,5% (2015) on weekdays, and to 20.4% from 26.4% on Sundays. These figures reflect the shift to the papers’ online versions, with weekdays rate at 20.2%. The significantly lower online readership on Sundays (12.5%) may indicate that special offers and supplements with the print editions help resist the decline. A new television channel, Alpha (linked to Alpha Greece) entered the market where four channels totalled 60% of the viewership since 2014. Alpha appears to have secured around 10%[4], with its news bulletin rating lower. Its penetration seems to affect more the small rather than the major players. As a result, the share of the five big channels jumped over 70%. The share of ANT1, the leading commercial channel was around 20%, while that of the public service RIK was 14-16% (spring 2016). RIK’s main news bulletin was rated higher (20-21%). Television reception via digital free-to-air transmission is receding as IPTV and cable TV are rapidly gaining ground. The shift is due to the expansion of broadband and the offering of exclusive transmissions of sports events, along with a variety of thematic content. Broadband penetration reached 83% in 2015, 5% more than in 2014, in a market of 313,000. Three players share the market of Internet, IPTV/Cable TV and telephony. They are, CYTA (64%), Cablenet – the only cable provider (31%) and Primetel (5%)[5]. Broadband penetration and speeds remain lower than EU average.

The media regulatory framework remains unchanged since the digital switch-over (2011); digital licences are still temporary, renewed annually. However, the ninth amendment of the constitution (2016) which allows interference with privacy (art. 15) ‘in the interest of transparency and the fight against corruption’ may have further implications on how media access sources and report information protected so far under the clause of privacy.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

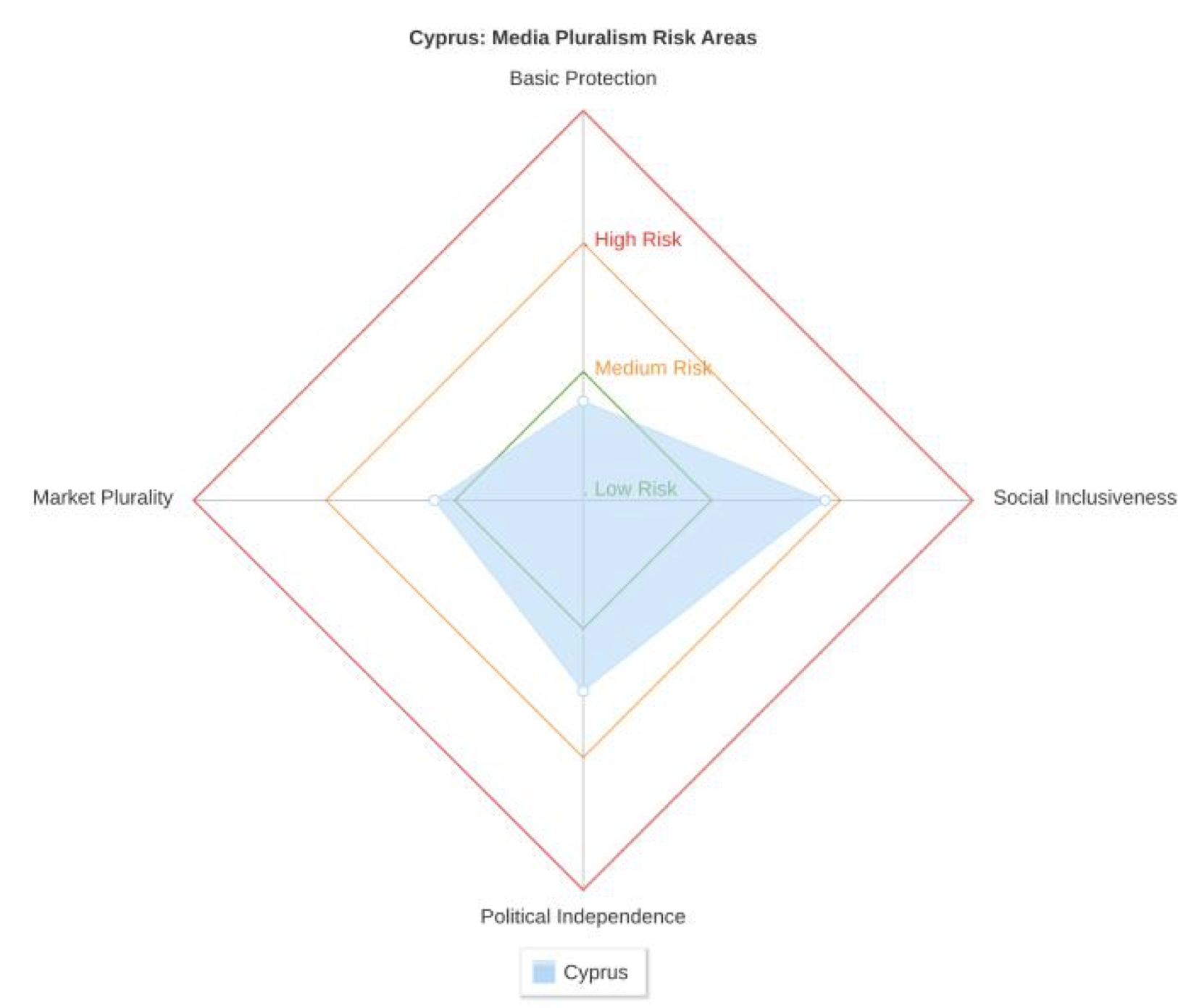

Overall, the state of freedom of expression and media pluralism is rather positive. The basic protection area exhibits low risk, while market plurality is faced with medium risk (at the lower end of the spectrum). Political control and interference with the media appear as medium risk to pluralism, while the limited importance given by the media to social inclusiveness poses a medium risk, bordering to high risk. However, as detailed below, specific indicators point to high risks.

Constitutional and legal provisions, and the application of the ECHR case-law by courts offer citizens safeguards for the protection of rights connected to freedom of expression. This applies also to freedom of information and media and journalists’ rights, which are protected by an independent media authority too. An issue of concern is the limited penetration and low speed of broadband.

Law enforcement ensures transparency in media ownership and effective avoidance of cross media concentrations. However, the implementation of the Top4 formula renders the actual horizontal ownership a factor of high risk to media market plurality. In addition, the economic crisis and competition by new media are threatening media viability. The crisis and the absence of state aids increase media vulnerability and exposure to external influences.

Although the media cover elections fairly and offer extensive access to political actors, the latter interfere in ways that threaten media pluralism. Interferences relate to the governance of the PSM, its funding and operation, as well as to state funding of the only existing news agency. They all pose major threats and high risks to pluralism. The non-transparent distribution of state advertising, although it appears fair though, is also problematic; rules, if any, and figures are not available publicly, rendering scrutiny impossible.

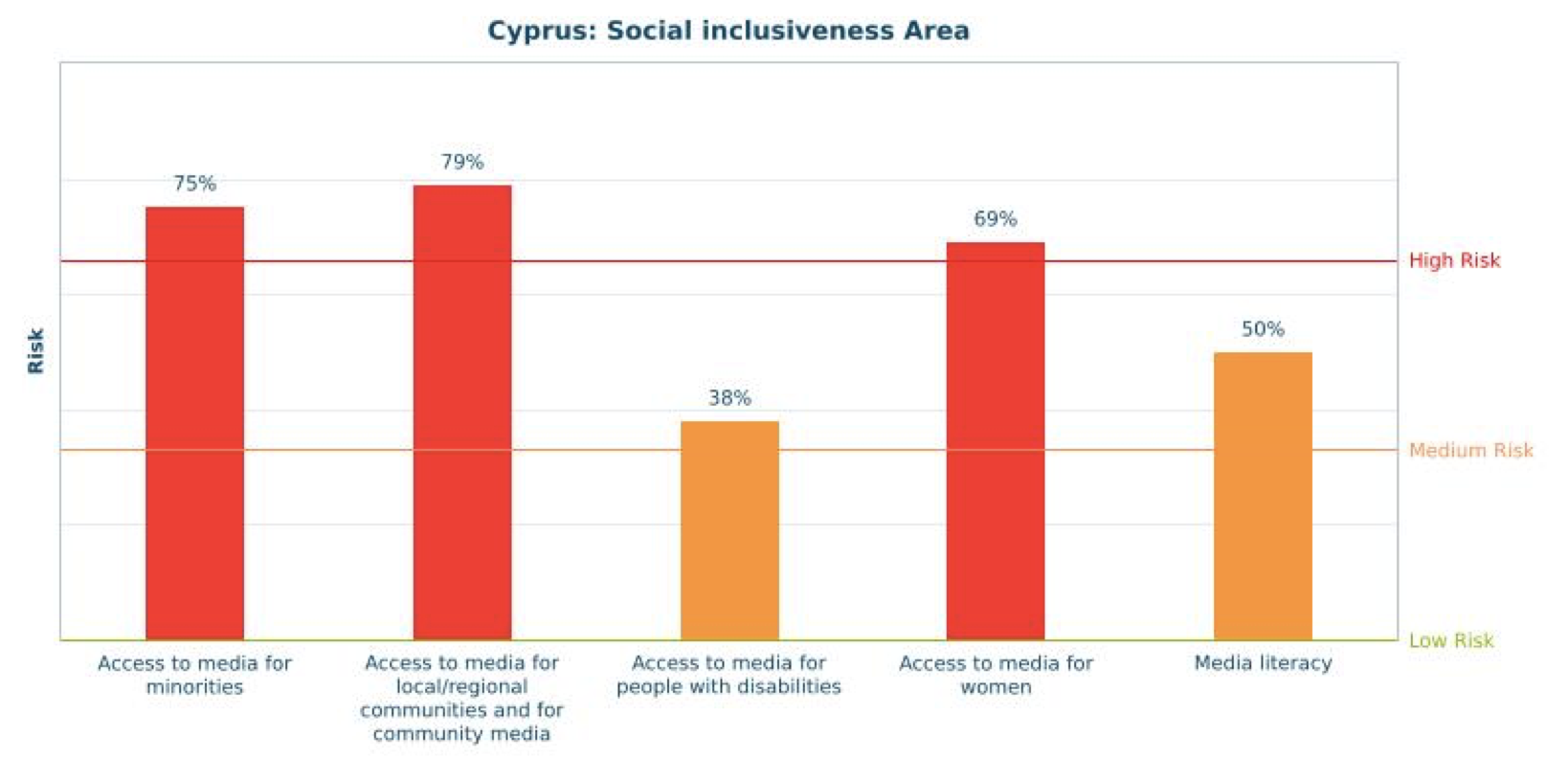

Access to the media mainly by mainstream groups is unfavourable to social inclusiveness; this is mostly worrisome, resulting in high risks to pluralism. Limitations in access to media for minorities, local/regional communities and women are coupled with the absence of community media. Similarly, the absence of comprehensive policies in media literacy and access to media for persons with disabilities poses medium risks.

Nevertheless, a more accurate assessment of the above requires that we take into account contextual and other factors. These factors often mitigate the negative impact of specific indicators, without, however, reversing the situation.

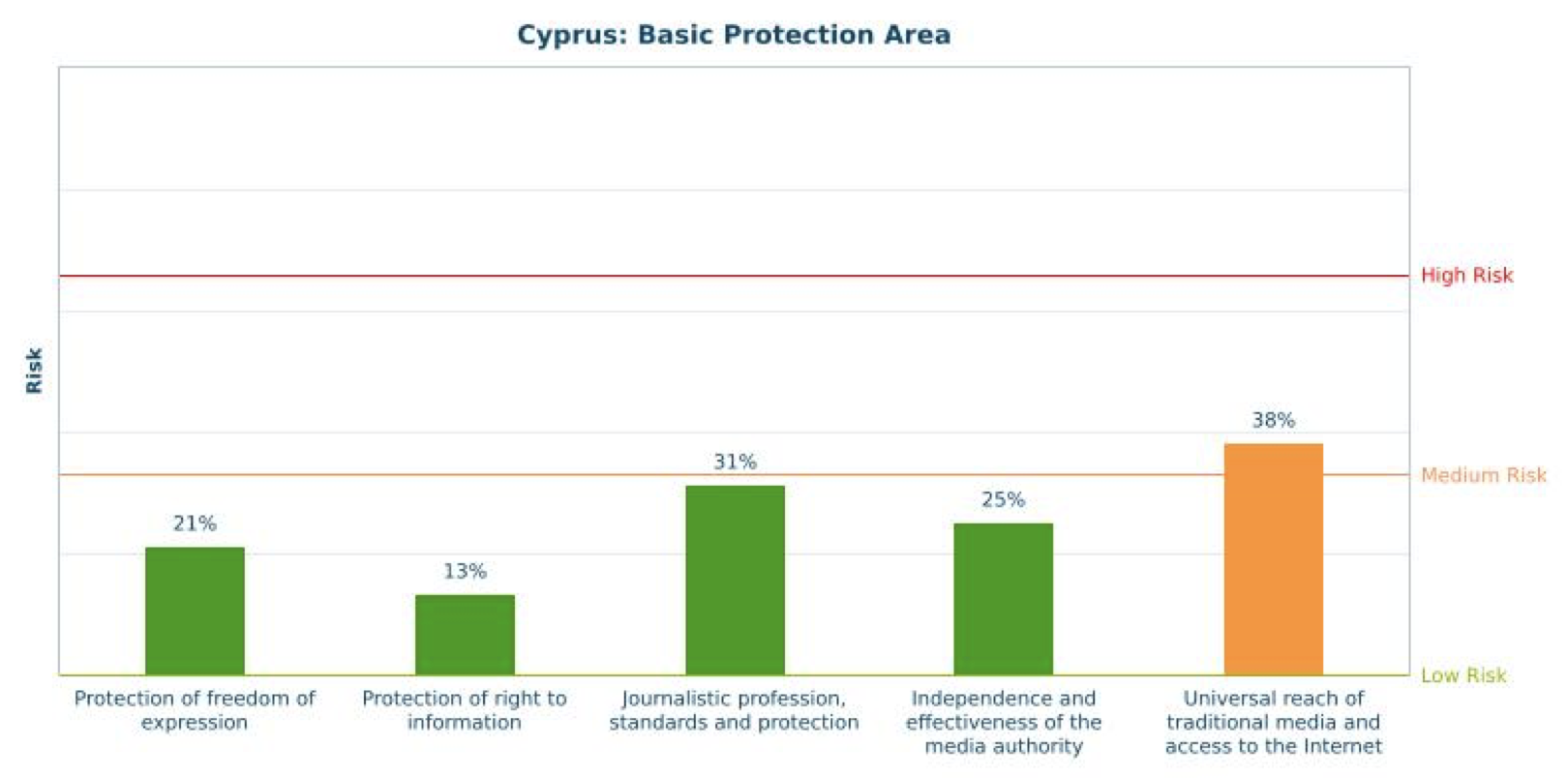

3.1. Basic Protection (26% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Freedom of expression and the related rights enjoy an overall effective protection, posing a low risk in respect of the basics. However, some areas need to improve in order to remedy weaknesses or gaps related to policies and measures enabling broader access to digital communications, to better – effective protection of media professionals and other. Cyprus is a signatory member of all major human rights international instruments. The guarantees offered by its constitution and legal framework abide with the relevant rules and principles of international law. The courts offer protection and remedies that are founded among other on the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights.

Cyprus is among the few EU countries that have decriminalised defamation, even though the Attorney General can authorise criminal prosecution in very specific cases. They relate to protection of the army, religious symbols and foreign officials. The lack of debate and clear answers regarding surveillance of online communication, and seizure of computers for investigative purposes lead to a medium risk for pluralism. Thus, even though the overall risk to freedom of expression is low, at 21%, it is not negligible.

The right to information is recognised as a component of free expression and is also a low risk at 13%. In specific sub-indicators, such as Access to information, a medium risk is present; it is connected to the lack of adequate answers when one seeks information held by the authorities. Adoption of a legal framework is still pending and policies applied are contradictory. Moreover, remedies, such as a recourse to the office of the Ombudsman or to the courts are deemed not satisfactory; they are time-consuming and entail costs for interested persons, not affordable by most people.

Access to and exercise of journalism are free, not hindered by any obstacles. Labour and other laws protect journalists’ rights and benefits, and ensure access to sources of information, requiring in some cases a professional card. However, the present conjecture makes the economic crisis a factor or a pretext for undue pressures on media professionals. In 2016 only 50% of journalists adhered to the sole trade union. Low rate professional representation poses a medium risk to pluralism. Other parameters are also rated at medium risk; they are, a weakened Union’s capacity to defend the profession’s rights, work conditions threatened by unemployment, and threats from suspected surveillance. The economic crisis appears to negatively affect the journalists’ will or power to consistently claim editorial independence or to defend salaries and benefits against arbitrary cuts. Overall, Journalistic profession, standards and protection faces a low risk (31%), which, however, is at the limit of medium risk.

The media regulatory system ensures a legally independent authority with its own budget and adequate powers to conduct its mandate. Its decisions are published regularly and are subject to judicial review only, with no room for government interference. However, other parameters are considered as posing medium risks: These are the membership appointment procedure, including selection criteria, doubts about independent /efficient operation in practice (emerged in 2015), along with transparency issues. In fact, the regulator has no obligation to draft a strategic plan, act in a target-specific manner or present any activity report. As a result the media regulatory aspect is rated at low risk, albeit at 25%. We note the appointment of a new governing body, in July 2016.

A problematic area in respect of basic protection of free expression relates to access to media, in particular to online media. Actual access to broadband and low speeds place Cyprus low in comparison to the EU average and pose a medium risk, with an overall risk for media access at a medium level (38%). Risks are mitigated by the universal coverage of both public and commercial radio and TV.

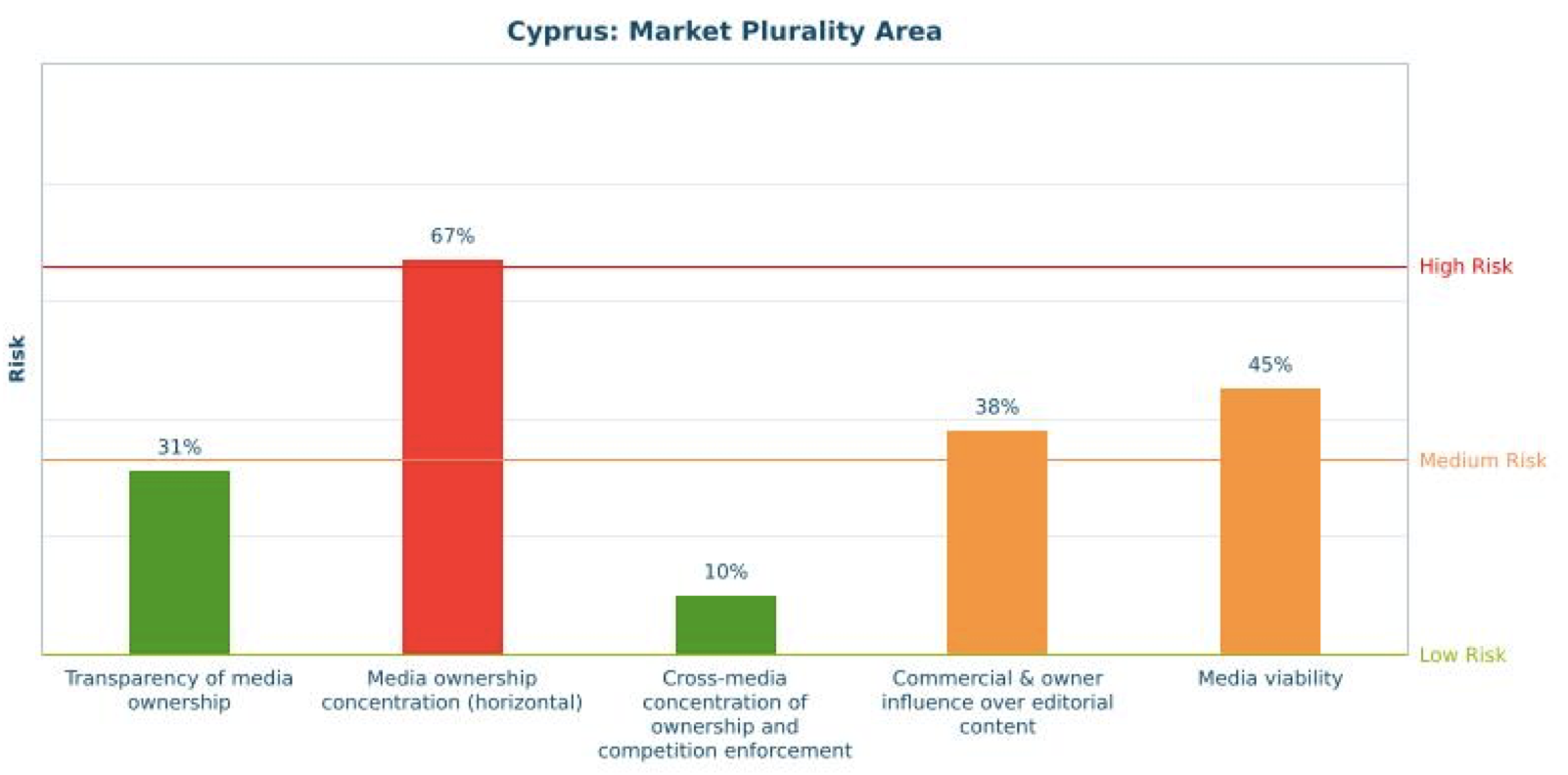

3.2. Market Plurality (38% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The situation in respect of actual market plurality presents an overall positive, low risk picture on transparency of media ownership and competition, and cross media ownership concentration. However, the market plurality cannot disguise a reality emitting alarming signs for media viability, influences by owners and commercial interests on editorial content, and horizontal media ownership concentrations.

Transparency in radio and television ownership vis-a-vis the authorities is almost absolute due to the licensees’ obligation to fully disclose the state of and changes in ownership. Failure to inform the regulator or ensure its approval prior to any change may be punished. Publication of this type of information is limited to the names of those holding over 5% of capital-shares, with no more details. Newspapers have no relevant obligations. Overall, the indicator on transparency is at low risk (31%), yet not negligible.

Audiovisual media ownership and control are strictly regulated. Rules provide for a 25% share-holding ceiling and constraints related to management and other factors. All changes need prior approval by the regulator. No relevant rules exist for newspapers. The implementation of the formula of “the Top4” for measuring eventual threats from media ownership concentrations points to a high risk situation. In all types of media, there are only four or five major actors, with their total audience and market share rates rising beyond 60% (radio, television) or up to 88% (television). A new television channel operating since early 2016 is changing the landscape. Concentration in the newspaper market is higher, with one daily having larger circulation figures than all other four dailies together. All the above limit media plurality and raise the risk to just over high level threshold (67%).

On a general note, however, given the small size of the market, media viability and independence may be a problem if the (traditional) media landscape is further fragmented as a means to achieve a lower Top4 share.

Cross media ownership concentrations and protection of a competitive media environment emerges as the most guarded area against risks. The strict rules on horizontal audiovisual media ownership thresholds, combined with the rules on cross media ownership – both to be found in law 7(I)/1998, leave little margin for breaches. Concentration is limited in the online media market, and aids to the PSM do not seem to critically affect competition. All the above diminish the need for the competition commission to intervene.

The role and influence of owners and commercial interests upon editorial content have been growing in recent years. Media professionals avow what is generally agreed, that pressures caused by the economic crisis and problems arising from competition from the new media have increased dependence on commercial interests. The latter are disguised as editorial content, in both the print media and their online editions. Additionally, employment insecurity facing the profession makes journalists and media reluctant to claim editorial independence. This limits also investigative media work on businesses. Thus, a medium risk at 38% is connected to unwanted influences.

Advertising income for all types of media shows slight increases in 2014. This derives from both survey data, providing nominative sums, and fragmentary accounts data submitted to the Radio Television Authority. However, this increase is neither sufficient to compensate eventual losses from the 2013 bail-in nor adequate to address financial pressures due to competition by new media and other factors. The absence of any state support scheme for media increases financial difficulties. The overall risk level to media viability is medium, at 45%.

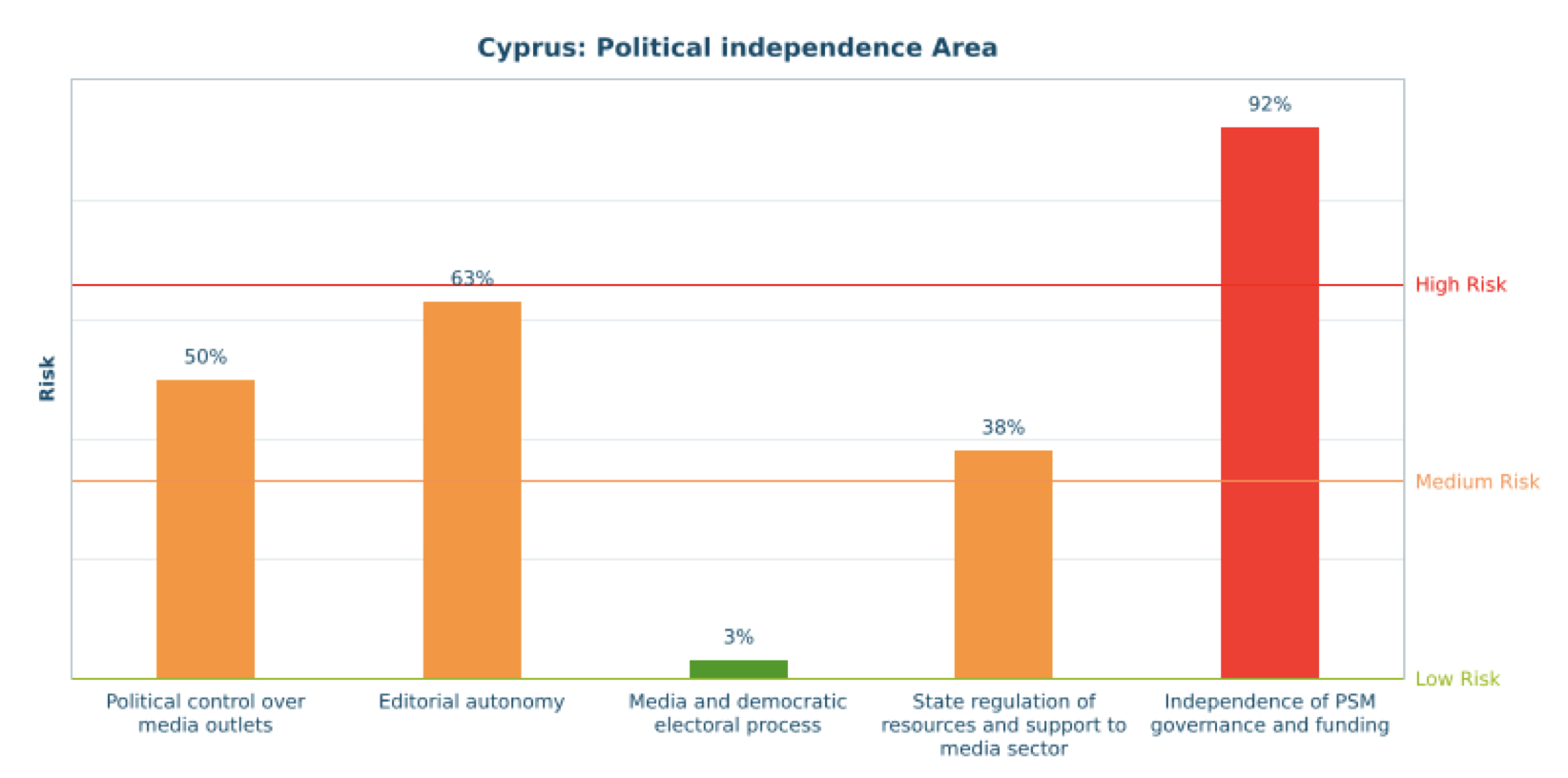

3.3. Political Independence (49% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Strict clauses regulating radio and television warrant pluralism in audiovisual media against ownership concentration or control, requiring also content impartiality. The relevant ownership thresholds and other constraints cover all persons, including politicians, and are efficiently enforced by regulators. The non-explicit exclusion of politicians from ownership and /or control of radio and television, as well as of the various types of media distribution networks is interpreted as posing a medium risk. In practice, however, political presence or control remain isolated phenomena. Constraints to political control of newspapers can only be enforced on the basis of the general rules on competition. However, all but one politically affiliated paper have vanished since the 1980s-1990s. This is assessed as a medium risk. The situation is different regarding the only existing news agency, governed by media professionals. Its budget relies almost exclusively on state funding, which makes it a case of high risk. Overall, the indicator Political control over media outlets is considered as posing a medium risk (50%).

Editorial independence is in theory warranted by both regulatory and self-regulatory provisions, with no reference or connection to appointments and dismissal of editors in chief. The rules make no or very limited provisions for mechanisms or procedures for the effective protection of journalists and avoidance of political interference with their work. However, the real issue lies with the pursuance of the owners’ political agendas rather than interferences by politicians. Thus, rating of this indicator as a medium risk (63%), very close to high, should be (re)considered in connection to more parameters and contextual elements. Existing content impartiality rules the public’s negative stance on politicised content and other factors mitigate, in practice, the risks.

Political actors, parties and politicians have ample opportunities to access the media and present their views and positions in a fair and non-discriminatory manner. Both PSM and commercial media are legally bound to cover daily political communication and electoral campaigns alike. Equal opportunities apply to political advertising that has to be clearly identified as such. Compliance to the rules in practice reduces risks to a negligible 3%.

Spectrum is the only state resource allocated in a transparent and fair manner; no other scheme of direct or indirect support to media exists. This poses high risks to the survival of traditional media that are also affected by the economic crisis and competition by new media. In addition, the absence of rules for the distribution of state advertising, even though it appears to be fairly done in practice, poses a medium risk. The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to media sector presents a medium risk (38%).

The most problematic issue for pluralism among all indicators in this monitor relates to the PSM, in particular interferences that gravely compromise its smooth functioning and independence. Adequate rules and criteria for the selection and appointment /dismissal of the governing council are absent, while the state decides unilaterally on funding and budget issues. In addition, parties interfere on political grounds with the budget and the daily operation of the PSM. Rules that ensure fair and transparent procedure in the appointment of the Director General remain an empty letter. As a result, risks against the PSM’s independence are very high, at 92%.

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (62% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Access to media for minorities in Cyprus is a complex issue given the small numbers of citizens belonging to ‘religious groups’, as mentioned in the Constitution, and a recent inflow of diverse groups of immigrants into the country (20% of the total population in 2011 census were immigrants). The PSM law requires that programmes be impartial and respect the interests and sensitivities of minorities, with no further provisions. In practice, ‘religious groups’ that are recognised by the law are given access to radio but not to television; they have no dedicated newspapers. The radio offers programmes in various languages. Overall, the indicator on Access to media for minorities poses a high risk at 75%. Beyond the indisputable need for explicit recognition of the right of minorities to access media, critical questions emerge: How can Cyprus meet access and proportionality requirements for citizens’ groups numbering in the hundreds or 3-4,000. Also, which policy frameworks to apply for media access for diverse immigrant populations, established in Cyprus relatively recently and, in many cases, allowed for short-stay periods. Finally, where should resources come from?

Questions are also raised in relation to Media access for regional/local communities and for community media, an indicator which reaches a high risk at 79%. Tens of radios operate locally and two television channels are received national-wide since the digital switch-over (2011). The law ensures access to carry platforms, but not the separation of local and national programmes and news, or the obligation to have local correspondents. However, in practice, all operators have local correspondents and cover local affairs. Support schemes exist neither for local nor for any media. All the above aspects point to high risks for plurality. However, the meaning of local/regional in objectively small countries and separation of local / national are questionable. A possible solution for Cyprus may lie on recognising and promoting community media, which would connect media with local communities and minorities.

Media access for persons with disabilities is promoted by recently introduced policies that are still developing. The relevant provisions apply also to VOD services, so that persons with hearing impairment or sight deficient are not excluded. Policies remain incomplete, which points to medium level risks (38%).

Promotion of gender equality and respect for women’s rights is the subject of a variety of laws, some very detailed ones. They are binding for all, including the PSM. However, the PSM has not developed any gender equality policy. Moreover, the PSM (new, 2016) governing council of nine members includes only two women. Overall, this indicator presents a high risk at 69%. While the absence of a PSM comprehensive gender equality policy is a serious failure, there is a need to contextualise this assessment and avoid an absolute cause-effect approach. The existing regulatory and normative frameworks are mitigating factors with regard to certain aspects of the issue and may reduce overall gender discrimination risks to medium level.

A policy framework on media literacy has been pending since 2012. However, the Pedagogical Institute of the ministry of Education has been promoting various initiatives in the primary and secondary education sectors focusing in particular on safety on the Internet. Many initiatives are undertaken in cooperation with the Radio Television Authority, responsible under the law for the promotion of media literacy. Some activities target also non-formal education. These initiatives seem insufficient to address problems of relatively low rate of basic digital usage skills (19%) and very low rate (9%) of basic digital communication skills that place Cyprus low among the EU28. As a result, the Media literacy indicator presents a medium risk at 50%.

4. Conclusions

Freedom of expression and media pluralism in Cyprus present an overall positive picture. This is mainly true in respect of basic protection and the framework for the preservation of market plurality. However, gaps and problematic aspects do exist. While media are generally independent from political control, they frequently reflect the owners’ political agendas. They are also vulnerable to increasing influences by commercial interests. Despite privileged media access, political actors interfere with the funding and operation of the PSM. Non-mainstream and other minorities groups, including women enjoy limited media access.

In the light of the MPM2016 results, the following challenges emerge for authorities and the media sector aiming at enhancing media pluralism.

Basic Protection of free expression

- The main challenge for authorities is to promote a universal penetration of broadband with higher speeds as a means to bridge the existing digital gap.

- The media need to rethink and re-define their role. Raising awareness on and defending journalists’ rights and editorial independence are key to pluralism and serving the public interest.

Market Plurality

- The media should take action towards clearing content from external influences and redeem media’s social role.

- The media should also experiment with new business models and revenue streams.

- The State needs comprehensive policies to assist mainly print media to survive and offer more titles. Aids and transparency in indirect subsidies would help media role for social inclusiveness too.

Political Independence

- Government and political parties must revise their approach to media, mainly PSM. This, and adequate law amendments should warrant unhindered public service operation by an independent in all respects PSM governing body, consultation in budget design and provision of resources.

- Mechanisms for ensuring editorial independence can only be efficient when media professionals are well aware of and claim this right. Effective defence of labour rights is key so that journalists speak out.

Social Inclusiveness

- The legal framework of PSM needs ample revision, in particular the definition of public service. Extensive rules should warrant inclusiveness and the obligation to design comprehensive policy frameworks on gender equality in media and minority groups.

- There is need for expanding the general provisions on inclusiveness in the law on commercial media so that they explicitly warrant access to the media for broad numbers of social groups.

- Community media must find a place in the law, with provisions for their development, including sources of funding, the means to support their operation and an effective long-term plan.

- Media literacy is of primary importance and long pending policy proposals must be adopted along with concrete implementation programmes.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT |

| Christophoros | Christophorou | Media Expert | — | X |

| Lia_Paschalia | Spyridou | Lecturer | University of Cyprus |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| Name | Family Name | Institution | Capacity |

| Panos | Panayiotou | Member Governing Council CYBC (PSM) | Representative of a broadcaster organisation |

| Orestis | Triggides | Cyprus Community Media Center (CCMC) | NGO researcher related to the media |

| Eleni | Mavrou | Dialogos Media | Representative of a publisher organisation |

| Dimitra | Milioni | Cyprus University of Technology | Academic |

| Costas | Stratilatis | University of Nicosia | Academic |

| Antonis | Makrides | Cyprus Union of Journalists | Representative of a journalist organisation |

| Antigoni | Themistokleous | Cyprus Radio Television Authority | Representative of media regulator |

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

Date: 2 December 2016

Place: University of Cyprus, Room 101, University Campus, Nicosia

List of participants (name, affiliation)

- Christoforos Christoforou, Principal Investigator MPM 2016 for Cyprus

- Lia-Paschalia Spyridou, University of Cyprus, co-investigator MPM 2016 for Cyprus

Team of experts

- Antigoni Themistocleous, Cyprus Radio Television Authority

- Orestis Tringides, Cyprus Community Media Center (CCMC)

University faculty

- Dimitris Trimithiotis, University of Cyprus (speaker)

- 2 Other members

Students to the Department of Journalism, University of Cyprus

Members of the public

Programme

- Address by Christophoros Christophorou

Short presentations

- The Economics of Pluralism in the new Media Ecosystem, by Lia-Paschalia Spyridou

- Pluralism, a concept not adequate enough to analyse the public sphere, by Demetris Trimithiotis, teaching faculty, University of Cyprus

- Evaluation of Pluralism by the Cyprus Radio Television Authority, by Antigoni Themistocleous, Officer of the CRTA

- Community Media, by Orestis Triggides, Cyprus Community Media Center (CCMC)

- Discussion

Key topics discussed

- The centrality of pluralism for a functioning democracy

- Different types of pluralism: media outlets, content, exposure

- A significant part of the meeting referred to the advent a new media ecosystem and the various economic dimensions of the media industry (entry barriers, horizontal and vertical integration, cost of media production)

- despite its heralded democratic character- in reality, the new media ecosystem consolidates concentration of media ownership

- legacy players have an advantage and tend to dominate offline and online

- the fragmentation of the audience promotes horizontal concentration

- despite the existence of laws regulating media ownership horizontal concentration is not avoided as powerful players monopolise the audiences’ attention

- media production, being an expensive activity, deters new players to enter the market

- new (international players) such as Facebook and Google acting as aggregators and intermediaries do not produce new content whilst controlling distribution which can also pose high risks for pluralism.

- questions raised: can existing tools of assessing pluralism work effectively in the new media landscape? Can there be pluralism within ad-supported media environments or should we examine the viability of alternative business models?

- The issue of media plurality (in terms of number of outlets) in relation to the content produced was also extensively analysed. It was argued that we cannot evaluate plurality effectively by analysing the number of players. Issues related to agenda setting and sources is equally important. For instance, in Cyprus the Cyprus news agency acts as a significant provider of news, whilst there is evidence of bias.

- Furthermore, it is important to take into consideration increasing instances of precarious labour in the creative industries, as they tend to work against plurality and towards homogeneous and commodified content.

- The last argument was confirmed by the findings of the Cyprus Radio Television Authority Report (2009-2012), which was briefly presented. Although according to the Report, the Cyprus media landscape is characterised by plurality (in fact there are too many players, especially in the radio industry, given the country’s size), most content revolves around specific formats. In the case of entertainment content, a strong tendency towards music formats was documented, while specific age groups, such as children and young people, are not catered for.

- Although the presentation of the Report confirmed the weaknesses of the existing methods, it was argued that the Cyprus Radio Television Authority (which is currently preparing the 2013-2016 report) has followed the same methods, and for the time being there is no intention of changing them.

- Extensive reference was also made to Community media and its role as a tool of active participation of the community and social inclusiveness.

Conclusions

- The new media ecosystem brings along new problems which need to be addressed with new laws and tools

- Assessment of structural pluralism proves inadequate as a measure to evaluate pluralism

- Qualitative aspects of pluralism are equally important to quantitative ones

- Official data, such as reports of independent bodies, may be able to provide a trend, but cannot (due to method weaknesses) provide truly reliable data

- The inefficiency of the traditional advertising model in the digital era consolidates commodification, intensifies precarious labour and leads to higher risks for pluralism

Other remarks

- The difficulty to compare pluralism between small and large markets

- Content pluralism, comprising a major aspect of pluralism, is by large understudied.

- Consumption patterns (exposure pluralism) need to be further analysed and studied in order to have a more comprehensive picture. To do so, we need to come up with new tools and measurements.

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] The report covers the media landscape of the Republic that is under effective government control. The island is divided since summer 1974. The pursuance of diverging goals by Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots since the 1950s created the Cyprus Problem. A coup instigated by the Greek Junta of Athens against President Makarios, in summer 1974, was followed by the invasion by the Turkish army. Efforts are underway to end the division of the Cyprus effected since then.

[3] Data GNORA, 2016 https://gnora.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mediagnosis_mar_may_2016_en.pdf covering the period March-May for years 2013 to 2016.

[4] See, https://www.agbcyprus.com/telegraph/telegraphCMS.php

[5] See, https://www.ocecpr.org.cy/sites/default/files/ec_report_fiixedtelephonybroadbandtelecombulletin_gr_13-05-2015_pk_mn_2_0.pdf