Download the report in .pdf

English – Flemish

Authors: Peggy Valcke, Pieter-Jan Ombelet, Ingrid Lambrecht

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016, under a project financed by a preparatory action of the European Parliament. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Belgium, the CMPF partnered with KU Leuven’s Centre for IT & IP Law (CiTiP), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

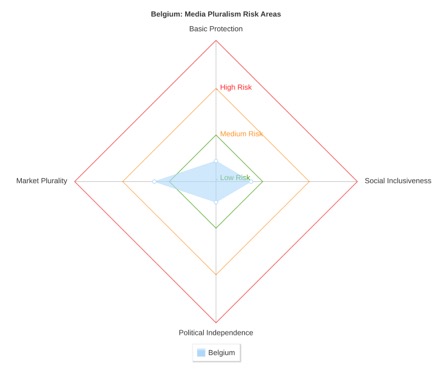

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk.[1]

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Despite being a small country, Belgium has three linguistic Communities: Flemish, French and German-Speaking.[2] During the successive state reforms (which started in 1970) the Community authorities were given more powers to regulate the radio and television broadcasting markets. As a consequence, each Community has its own (audiovisual) media law and a separate media regulator (with sometimes varying tasks and competences). For example, the regulator of the French Community, the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel (CSA), is authorised to monitor concentration indices and take regulatory action if it concludes that the media market in the French Community is becoming too concentrated, whereas the Vlaamse Regulator voor de Media (VRM) of the Flemish Community only has the power to ‘map’ media concentration and publish annual reports about the state of media markets.[3]

This linguistic diversity has resulted in the economic reality of supporting two separate media markets: certain media companies concentrate on the north of Belgium with its predominantly Flemish speaking population, whereas other companies address the predominantly French-speaking population in the south of Belgium.[4] This widely accepted division of the media markets[5] results in small media markets compared to neighbouring countries like France, Germany or the Netherlands.[6]

Moreover, the increased autonomy of regional authorities explains the need to assess the indicators of the Media Pluralism Monitor for both markets separately for those aspects which fall under the competences of the linguistic Communities (e.g. adopt legislation on radio and television broadcasting, decide on subsidies for the press, etc.). Nevertheless, the reader should understand that, despite the fact that the Dutch speaking media almost exclusively target the Flemish Community and French speaking media are predominantly consumed by the population of the French Community, we considered those media outlets as “national media”, and not as regional media. The reason is that the Belgian population has access to all media outlets provided in both languages irrespective of location.[7] In contrast, the situation was assessed at national level for those indicators relating to issues regulated by the Federal authorities (such as the availability of broadband).

The Belgian public also has access to a broad range of foreign media outlets, both print publications and audiovisual media which are available via cable, satellite and via the internet. Especially the French-speaking part of the country, TV channels from neighbouring countries are very popular, in particular the channels from the French public service broadcasting organisation and from the TF1 Group, and the Luxembourg based commercial TV station RTL. Similarly, the German-speaking population mostly watches television channels from Germany (including terrestrial). In addition, online media consumption is on the rise, broadening access to a variety of offerings from international media players.[8]

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

This report offers the results of a detailed measurement of 20 indicators (composed of 200 variables) on media pluralism, grouped into four risk areas: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. It confirms Belgium’s good position on the World Press Freedom Index. When it comes to fundamental protections of press and media, Belgium scores particularly well, albeit it with some ‘wrinkles’ on the surface. These irregularities are mostly practical issues preventing journalists from fulfilling their role as ‘watchdogs of society’ to the fullest. Arbitrariness in accessing public information, job insecurity and the threat of criminal defamation sanctions provide some examples.

The economic situation of Belgium’s media markets is a more complex story. With three different language communities, markets are very small and media actors very concentrated to stay afloat. Recent years have witnessed a growing consolidation between media actors (within and across sectors). Belgium has focused its energy on maximum transparency to help mitigate the risks of such concentrations.

On paper, Belgium benefits from a variety of guarantees to preserve independence of the press, from both political and commercial influencers. For Flanders, experts in the field have pointed out however, that these ‘paper guarantees’ do not always unequivocally apply in practice. Influential links such as these are often subtle and difficult to prove, but not necessarily problematic.[9]

Finally, with regard to social inclusion, the fragmentation of Belgium’s media landscape is at the core of Belgium’s challenges. With three different communities sharing powers over media affairs, attempts to guarantee inclusion of minorities has proven difficult due to a high level of policy fragmentation. Nevertheless, countless efforts are made on both national and regional policy levels to overcome this obstacle. For example, Belgium scores exceptionally well on including persons with a physical disability, but is still working towards better access to media for women.

Belgium’s media pluralism map does not paint a consistently rosy picture because of a number of hurdles resulting from the limited size of media markets, policy fragmentation and some gaps between legal theory and practice. Nevertheless, for three out of the four areas measured, Belgium scores a low risk; only for the area of market plurality, a medium risk was detected. The overall conclusion of the report is therefore positive.

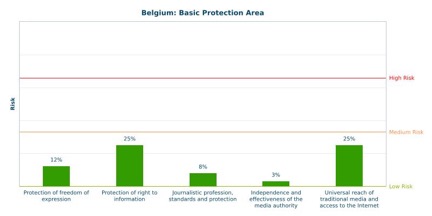

3.1. Basic Protection (15% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Belgium has an overall positive score on basic protections, which is reflected in its position as number 13 in the 2016 World Press Freedom Index. Belgium’s strengths come from a strong recognition of fundamental rights, such as the freedom of expression and the right of access to information, and from its protection of the journalistic profession, its sources and independence. However, within all these categories, some points still leave room for improvement.

In the Protection of freedom of expression indicator, Belgium obtained a medium risk score for one variable as a result of the continued criminalization of defamation (defamation is still a criminal offense under Articles 443 to 452 of the penal code and is punishable by imprisonment), despite the Council of Europe’s call from 2007 to abolish prison sentences for defamation without delay[10]. In practice however, public prosecutors will only rarely (if never) use criminal defamation law due to the difficulties and costs of a trial by jury (Court of Assize), which is mandated for press offenses (with the exception of hate and racist speech cases) by Article 150 of the Belgian Constitution.[11] Such violations are thus traditionally adjudicated in civil courts for claims of personal damage. Even though in practice the laws may not be applied, the possibility of criminalization still remains present. In regards to filtering, blocking and removing by ISPs, the Belgian Internet Service Provider Association (ISPA) has adopted a Code of Conduct;[12] there is Belgian case law clarifying that ISPs cannot be expected to, or be held accountable for, a priori and generally filtering out and consecutively removing of content that is presumed to be illegal or harmful, due to the disproportionality of such a demand in light of fundamental rights;[13] and, finally, we found no evidence of arbitrary filtering.

A minor risk was detected in relation to the indicator on Protection of the right to information. The risk arises from problems in practice including arbitrariness and misused appeal mechanisms. In its recent annual reports,[14] the federal Commission for the right of access to government-held information criticized the reluctance of many federal administrative agencies to honour access requests[15] and the lack of a pro-active attitude towards ensuring open government (Article 32 of the Belgian Constitution not only grants citizens the right, in principle, to access government-held information, but also entails a duty for the government to organize itself in such a way that administrative documents can be made easily available).

For the indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection, data showed that Belgium scores a low risk relating to access to the profession, but in practice there appear to be obstacles relating to job insecurity. Belgium scores a medium risk in this regard as even though a journalist’s pay is similar to that of a teacher, their job security is much lower. Newly graduated journalism bachelors have a 12.4% chance of finding a job as a journalist within the first year after graduation. Of the journalism masters, this is even lower: 11.8. Lastly, although cases of attacks or threats to the physical safety of journalists in Belgium are generally rare,[16] this criterion was assessed as medium risk. The main reason for this is the terrorist events that took place in Brussels in March 2016 and which temporarily led to an increase of physical and online threats made towards reporters (together with two recent cases of politicians attempting to chill press freedom).

The indicator on the effectiveness and independence of the different media authorities in Belgium shows a mere 3% risk due to the existence of regulatory safeguards .[17]

For the indicator on Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet (including net neutrality), Belgium obtained a score of low risk. A specific concern is the high level of concentration on the market for internet access (with the Top4 ISPs controlling 92% of the market). In relation to net neutrality, regulation 2015/2120 of 25 November 2015 laying down measures concerning open internet access has entered into force in Belgium as of 30 April 2016. Upon invitation of Belgium’s minister for telecommunications, the Belgian Institute for Postal Services and Telecommunications (BIPT) analysed Proximus’ zero-rating practices in light of the new open internet rules. The BIPT found no discriminatory practices between applications, nor any other elements that may inhibit free internet consumption by their users.[18]

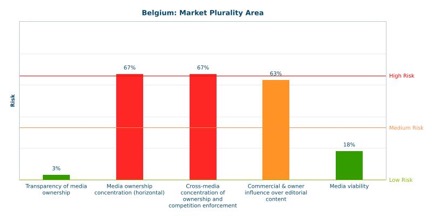

3.2. Market Plurality (44% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Similarly to the 2014 report, the indicators on market plurality in Belgium show a problematic situation. Nuance is needed with regard to the harsh statistics of having 2 out of 5 indicators showing a high risk, because of the size of the market and in the light of Belgium’s well developed regulation on ownership transparency.

As explained in the introduction, there is no such thing as a “Belgian media market”. Most indicators have been assessed on a regional level (for the Flemish speaking market and the French speaking market), which often resulted in high risk assessments. Only a handful of companies own all media outlets on the Flemish and French markets. In Flanders, two major groups, Mediahuis and De Persgroep, control 100% of the national daily newspapers (except for the freesheet Metro), whereas Concentra (part of Mediahuis) owns all Flemish regional newspapers (Gazet van Antwerpen and Belang van Limburg) as well as some of the regional TV channels. In the French speaking Community, Rossel Group (owner of Sud Presse) dominates the newspaper market (60%) with only two competitors controlling each 20% of the market (on the one hand IPM Group and on the other hand Editions de l’Avenir which is owned by the Walloon cable operator Nethys. Concentration reaches similar high levels in the radio and TV markets, resulting in very high concentration indexes and, hence, showing high risks for the Flemish and French speaking markets. As previously mentioned, this can be explained on the basis of the small size of the markets. Nevertheless, due to language overlaps with our neighbouring countries, it needs to be borne in mind that France, Germany and Netherlands based (terrestrial) media carry significant importance within the Belgian media landscape.[19] A wide range of alternative TV channels and video services is made available via cable and satellite, and – to a growing extent – via the internet, offering opportunities for foreign media players to cater for the needs of both mainstream and minority groups in Belgium.[20]

A second factor which may explain the high market concentration is the general lack of sector-specific anti-concentration rules. Apart from some restrictions on the accumulation of radio or TV licenses, the regional media laws do not contain specific thresholds or procedures for (cross) media mergers (which is mainly the result of the division of powers in Belgium between the federal state and communities, limiting each legislator’s scope for action). The French Community legislator has since 2003 entrusted its media regulator, the CSA, with the power to assess the existence of “significant positions” on a market, and take action where appropriate, but this system is rarely implemented in practice.

General merger control rules, which are laid down in the federal Code of Economic Law, also apply to the media sector. In some cases, the federal competition authority attaches conditions to the approval of a merger conditions with the goal of ensuring diversity of media content offers (e.g. concentration of Corelio and Concentra into Mediahuis).

Despite the previous concentration risks and issues, the overall score remains at a borderline high risk. The numbers were somewhat mitigated thanks to a positive evaluation of Belgium’s strong and effective rules on transparency and merger control, including remedies that can be imposed by regulatory authorities.

To conclude, there is a high level of ownership concentration in the Flemish Community in the television, radio, newspaper and internet market. For the French speaking Community, the level of concentration is even higher. Recently, there has been intense criticism following a number of mergers in the media sector (such as the merger of the n°2 and n°3 newspaper publishers in Flanders, Corelio and Concentra, into Mediahuis in 2013; or the take-over of SBS Belgium by Telenet through the acquisition of 50% of the shares in De Vijver Media in 2015; or the acquisition in 2013 of the newspaper publisher Editions de l’Avenir by the Walloon cable operator Nethys). The pluralism of media ownership is clearly affected by this high concentration. This may eventually also have a negative impact on the diversity of media content. However, in order to maintain the economic viability of the Belgian media companies in an era of decline in advertising and subscription revenues and increasing competition with global internet players[21], a high level of concentration seems inevitable. Moreover, the risks presented by this concentration are (at least partially) mitigated by transparency obligations imposed on media companies, mainly vis-à-vis the regulators who publish annual reports (in the case of the VRM in Flanders) or dynamic online databases (in the case of the CSA in the French Community) to inform the general public about the level of media concentration and ownership structures of media companies.[22]

Considering the context as laid out previously, in which the media sector is struggling under a decline in both advertising and subscription revenues, the indicator in relation to commercial and owner influence is showing a medium risk bordering to a high risk. In interviews with journalists it has surfaced that due to an increasing importance of audience reach they have felt pressure to write more popular content than they otherwise would.[23]

Finally, with regard to economic viability of media (low risk), statistics show that revenues of radio and audiovisual media services on the Flemish market combined have slightly increased over the past two years.[24] Revenues of newspapers and magazines are in decline, as well as readership figures, even when factoring in digital readership.[25] The decline has been steeper amongst French-language newspaper groups.[26] Media organizations are thus exploring alternative sources of revenues, such as crowdfunding and donations, e-shops and online platforms[27], but in general most organizations still rely on traditional revenue streams from subscriptions and advertising.

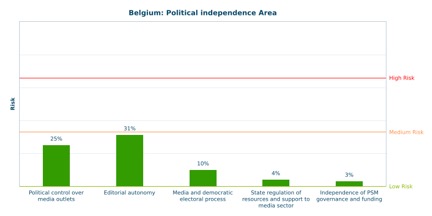

3.3. Political Independence (15% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

In the area of Political Independence results show low risks. However, two indicators scored a close-to-medium risk: political control over media outlets, and editorial autonomy. This can be explained by the fact that legal safeguards for political independence only exist for the broadcasting sector (radio and television), in contrast to newspapers and media distribution (leaving aside the general constitutional protection of freedom of expression and press freedoms, and self-regulatory codes of ethics for journalists). Variables on legal limitations to direct and indirect control of newspapers by party, partisan group or politicians had therefore to be answered negatively, as newspapers have no legal obligation to put in place an editorial statute; instead there is a traditional informal system in place. Furthermore, news agencies and media distribution networks also do not have a legal obligation to ensure political independence, but experts agreed that, in practice, the overall risk of political interference is low. However, some indicated that there is a subtle link between politics and media ownership, mostly situated in relation to those media organisations that (at least partially) depend on governmental finances and/or support.[28] They also indicated that these links are very difficult to prove.

For the indicator on Editorial autonomy, it is to be noted that there are no regulatory safeguards to guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief. In practice, stakeholders have, on the one hand, reported no cases in which a certain appointment or dismissal was considered politically influenced, but on the other hand, have agreed that there is a lack of hard evidence with regard to genuine independence from political influences in editorial content.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process again shows a low risk. For the Flemish Community this can be explained by the existence of legal (besides ethical) rules on impartiality and fair political representation on PSM and commercial broadcasters (Art.39 Flemish Broadcasting Act 2009), and evidence of effective implementation of those rules. The French Community has similar rules pursuant to Art. 36, 3° French-community Audiovisual Media Act 2009, a number of guidelines provided by the CSA (French Community media regulator) and the management contract of the RTBF. Politicians in both language communities have equal access to the media regulator in case of bias and/or unfair representation. A number of such complaints were brought before the Flemish Media Regulator who, however, did not find undue bias towards specific politicians[29] (except in one case). Paid political advertising is allowed and regulated by the media laws of the communities.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to media sector scores low risk. There is a legal framework for the distribution of state advertising, and the direct and indirect state subsidies to media. Still, experts suggest a medium risk on the allocation of direct subsidies from the federal government, emphasizing that they are distributed to media based on a set of rules, but that it is unclear whether these rules are fair. For instance, news media initiatives (e.g. www.stampmedia.be, an online press agency for and by youngsters) have criticised the fact that most of these subsidies are assigned to traditional media outlets.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding again shows a very low risk. There are extensive regulatory safeguards (in the media acts and management contracts), which are overseen by independent regulatory authorities, both in the Flemish and in the French Community. Additionally, the Council of State is competent as appeal mechanism. There have been no cases before these bodies that provide any cause of concern in relation to independence of PSM.

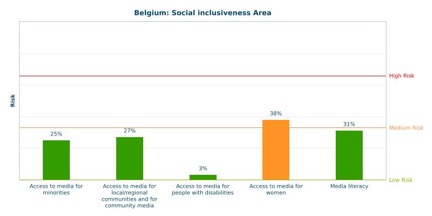

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (25% – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Access to media for minorities is at low risk in Belgium according to the Monitor assessment. However, within this indicator, minorities’ access to airtime on PSM channels was scored as medium risk. Legal obligations with regard to third-party programming on PSM have been eroded over the years, but PSM still have the obligation to represent the diverse ideological and sociological groups in society in their programming. Historic (rather complicated) regional regulations (based on the ‘Culture Pact’ of 1973) guarantee inclusion of philosophical and ideological associations in PSM. However, other minority groups, i.e. based on racial or sexual characteristics, generally do not benefit from similar legal safeguards (apart from general anti-discrimination laws). PSM (VRT and RTBF.be) do have to observe certain duties in relation to both minority groups and gender issues (including the development of a diversity policy), as specified in their management or public mission charter.

Unfortunately, the lack of empirical data makes it difficult to give an objective answer to the questions relating to the size of the minority population and the proportionality of access to airtime on TV and radio for minorities, and dedicated newspapers to minorities. [30] Hence, the relevant variables were coded as no data and were not counted towards the total score of the indicator Access to media for minorities.

The indicator on Access to media for local/ and regional communities was also assessed as low risk. However, the variable on support to community media through subsidies or other policy measures was coded as medium risk. Different policies in Flanders and Wallonia have resulted in a fragmented system of subsidies and protection of community media.

Belgium scored a very low risk on access to media for people with disabilities due to its well-developed policy and regulatory framework of both language communities, enabling assisting technologies ranging from subtitling, audio description, sign language and audio subtitling to access services for television and programmes.[31]

The indicator on Access to media for women was coded as medium risk. The scores on variables based on the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) 2015 report for Belgium[32] showed that women are still overtly underrepresented in news media, both as ‘news subjects’ and as ‘reporters or presenters’, in both online and traditional media. Moreover, a big gender gap exists regarding news personnel, in radio, television and print media. The high risk assessment on these variables was mitigated by Belgium’s legislative and policy efforts, including an effective equal rights law that applies to employment of women in media organizations and a comprehensive gender equality policy.

Belgium scored low risk on Media literacy, albeit close to medium risk. This is the result of a good presence of media literacy in the education curriculum of both language communities (low risk), in combination with a limited extent of media literacy in non-formal educational settings (medium risk). Belgium scores medium risk regarding the share of Internet users that have at least basic digital usage and communication skills. Recently, various and extensive initiatives on media literacy have been started in Belgium, of which the Flemish Knowledge Centre for Media Literacy (‘Mediawijs.be’, anno 2013) is one example.

4. Conclusions

We can conclude that Belgium scores relatively good in relation to media pluralism.

It receives an overall positive score on Basic Protection, which is reflected in its relatively good position in the most recent World Press Freedom Index. Strong points include Belgium’s strong recognition of fundamental rights and safeguards for the journalistic profession. Points that leave room for improvement include the continued criminalization of defamation, problems in practice with arbitrariness and misused appeal mechanisms for the right to information, and practical obstacles for the journalistic profession relating to job insecurity.

As in the 2014 report, the analysis of the economic indicators in the domain of Market Plurality shows highly concentrated markets, with multiple cross media links between market players. This results in a high risk for 2 of the 5 indicators. Recent consolidation in the sector may however explain the low risk for media viability, as such consolidation allows players to create synergies and jointly invest in digital and online strategies. Another mitigating factor is the existing regulatory framework on transparency of media ownership and the permanent monitoring of media concentration and ownership structures by the Flemish and French Community media regulators (resulting in a low risk for the indicator on transparency of media ownership).

In the area of Political Independence risks are mostly low for Belgium. Some experts indicated that there is a subtle link between politics and media ownership, mostly situated in relation to those media organisations that (at least partially) depend on governmental finances and/or support.[33] However, they also indicated that these links are very difficult to prove and may thus unknowingly pose a reason for concern.

With regard to Social Inclusiveness, the indicators show low to medium risks. Historic (rather complicated) regional regulations (based on the ‘Culture Pact’ of 1973) guarantee inclusion of philosophical and ideological minority groups in cultural matters (including broadcasting). However, other minority groups, i.e. based on racial or sexual characteristics, generally do not benefit from similar positive actions (apart from general anti-discrimination laws) with the exception of PSM, who have to observe certain levels of minority participation (as specified in management charters). Additionally, Belgium is currently making efforts to improve access for women and has developed several initiatives with regard to media literacy to overcome their current shortcomings in this respect.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Peggy | VALCKE | Professor | KU Leuven, CiTiP | X |

| Pieter-Jan | OMBELET | Research assistant | KU Leuven, CiTiP | |

| Ingrid | LAMBRECHT | Research assistant | KU Leuven, CiTiP |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Dirk | Voorhoof | Professor media law | Ghent University; University of Copenhagen |

| Hilde | Vandenbulck | Professor communication studies and media policy | University of Antwerp |

| Elise | Defreyne | Legal researcher | Université de Namur |

| Ingrid | Kools | Economist | Flemish Media Regulator |

| Pol | Deltour | National Secretary | Journalist Organisation VVJ/AVBB |

| Katrien | Lefever | Inhouse company lawyer | Medialaan (largest commercial TV and radio operator in Flanders) |

| Margaret | Boribon | Secretary General | Copiepresse (newspaper copyright management company) |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Next to the three Communities, there are also three Regions: the Flemish, Walloon and Brussels-Capital Region. The Communities mainly have powers in the domains of culture (theatre, libraries, audiovisual media, etc.) education, health care, social welfare and protection of youth; the Regions are competent for economic affairs (agriculture, energy, employment, city and local transport), environmental planning and tourism.

[3] Article 7 French Community Coordinated Act on Audiovisual Media; Article 218, §2, 8° Flemish Act on Radio and Television Broadcasting.

[4] No separate market for German-speaking media has been assessed, given the small scale of it. This was decided by the research team already during the previous implementation round, in consultation with the stakeholders and the Medienrat (the media regulator of the German-speaking Community in Belgium). In 2014, Mr. Yves Derwahl of the Medienrat confirmed that the German-speaking population mostly watches television channels from Germany, and has access to a wide range of media outlets operating in the Flemish and French Community. Only three local media providers are active in the German-speaking Community, solely offering radio services (BRF, Offener Kanal Ostbelgien and Private Sender). This situation has not changed.

[5] Valcke, P., Groebel, J. and Bittner, M. (2016). “Media Ownership and Concentration in Belgium”, in Noam, E. (ed.), Who Owns the World’s Media? Media Concentration around the World, Oxford University Press.

[6] The definition of a small media market in the MPM user guide of 2009 stated: Within this profile, countries are grouped according to the size of their media market measured in terms of total audience, or alternatively total revenues. A media market is defined as small when the population is under 20 million people, or alternatively the total revenues are up to $150 billion. Media markets exceeding 20 million people, or alternatively $150 billion in revenues are considered medium or large. For more information, see Valcke, P., Picard, R., Sükösd, M., Sanders J. et al, Independent study on Indicators for Media Pluralism in the Member States – Towards a Risk-Based Approach, European Commission, 2009, Volume 2: User Guide, 358 et seq.

[7] The media policy of the bilingual region Brussels-capital falls within the competences of both the Flemish and French Community. Media consumption in that region has been taken into account in assessing both markets.

[8] For more information about online news consumption in Belgium see: RISJ Digital Report 2016, p. 56 – 57, accessible at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf (03.03.2017)

[9] De Keyser J., Journalistieke autonomie in Vlaanderen: onderzoeksrapport in opdracht van het Kabinet van de Vlaamse minister van innovatie, overheidsinvesteringen, media en armoedebestrijding, Gent, Steunpunt Media, 2012, accessible at: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/3039856/file/3039872.pdf (03.03.2017)

[10] Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly, Resolution 1577 (2007) Towards decriminalization of defamation, 4 October 2007.

[11] Since the Second World War, the public prosecutor has only on three occasions brought a case before the Court of Assize. In these three cases, the Court of Assize has not yet convicted anyone on the basis of article 150 of the Constitution. Regardless of any future convictions, the extension of the definition of press offences to online publications by the Belgian Court of Cassation in 2012 can be considered a broadening of the de facto de-penalization.

[12] For an overview of these remedies, please read the Code of Conduct by the Belgian Internet Service Provider Association (ISPA) at: https://www.ispa.be/code-conduct-nl/ (03.03.2017)

[13] For example: the Pirate Bay case of the Antwerp Court of Commerce. For more information on this particular case, read: Antwerp (1st ch.) n° 2010/AR/2541, 26 September 2011, AM 2012, liv. 2-3, 216. Other relevant Belgian case law on this matter includes the notorious SABAM cases (CJEU, 24 November 2011, Scarlet v SABAM, C-70/10 and CJEU, 16 February 2012, SABAM v. Netlog, C-360/10), as well as the eBay case (Comm. Court Brussels (7th Ch.), 31 July 2008, Revue du Droit des Technologies de l’Information, 2008, n°33, p. 521 et s.

[14] See in particular the 2013 and 2015 reports, available via https://www.ibz.rrn.fgov.be/nl/commissies/openbaarheid-van-bestuur/jaarverslagen/.

[15] Stating that they “still insufficiently start from the perspective that all administrative documents are public and that requests for information only can be refused when there is an exception and that this exception has to be motivated” (Belgian Federal Commission for the access to, and re-use of administrative documents, Annual report 2013, p.13).

[16] Freedom House, Freedom of the Press 2015, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FOTP%202015%20Full%20Report.pdf

[17] For more information on the functioning of these authorities, please read: Study on “Indicators for independence and efficient functioning of audiovisual media services regulatory bodies for the purpose of enforcing the rules in the AVMS Directive” – INDIREG, p. 98-100, accessible at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/study-indicators-independence-and-efficient-functioning-audiovisual-media-services-regulatory-0 (03.03.2017) and in a similar context “A study on Audiovisual Media Services – Review of Regulatory Bodies Independence” by the EU AVMS Radar, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/news/study-audiovisual-media-services (03.03.2017)

[18] “Mededeling van de Raad van het BIPT van 13 februari 2017 met betrekking tot een overkoepelende analyse aangaande de postale behoeften in België”, accessible at: https://www.bipt.be/nl/operatoren/post/universele-en-niet-universele-postdiensten/mededeling-van-de-raad-van-het-bipt-van-13-februari-2017-met-betrekking-tot-een-overkoepelende-analyse-aangaande-de-postale-behoeften-in-belgie (08.03.2017).

[19] See by example the market share of French native media actors on: https://www.csa.be/pluralisme/audience/secteur/1 (03.03.2017).

[20] For more information about online news consumption in Belgium see: RISJ Digital Report 2016, p. 56 – 57, accessible at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf (03.03.2017).

[21] Noam, Eli M., and The International Media Concentration Collaboration. Who Owns the World’s Media?: Media Concentration and Ownership around the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016, 1440p.

[22] For more information on this database, please visit: https://www.csa.be/pluralisme/.

[23] De Keyser J., Journalistieke autonomie in Vlaanderen: onderzoeksrapport in opdracht van het Kabinet van de Vlaamse minister van innovatie, overheidsinvesteringen, media en armoedebestrijding, Gent, Steunpunt Media, 2012, available at: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/3039856/file/3039872.pdf (03.03.2017).

[24] VRM, Report on Media Concentration 2015, figures 37 and 46, available at: https://www.vlaamseregulatormedia.be/nl/over-vrm/rapporten/2015/rapport-mediaconcentratie (06.03.2017), a more recent report with numbers for the year 2016 is also available at: https://www.vlaamseregulatormedia.be/nl/over-vrm/rapporten/2016/rapport-mediaconcentratie (06.03.2017)

[25] VRM, Report on Media Concentration 2015, figures 56-59.

[26] RISJ Digital Report 2016, p. 56 – 57, accessible at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf (06.03.2017).

[27] Respectively: Médor, Dewereldmorgen.be, Mediahuis and Medialaan.

[28] Eg. MediAcademie, KIK, VAT-exemptions, Postal services, … For more information on potential political influence on the media, please consult: De Keyser J., Journalistieke autonomie in Vlaanderen: onderzoeksrapport in opdracht van het Kabinet van de Vlaamse minister van innovatie, overheidsinvesteringen, media en armoedebestrijding, Gent, Steunpunt Media, 2012, accessible at: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/3039856/file/3039872.pdf (03.03.2017)

[29] See by example the cases: B. Valkeniers en Vlaams Belang t. Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroep, beslissing 2009/025, 24 februari 2009; Frank Vanhecke t. Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroep, beslissing 2007/0032, 26 juni 2007; PVDA+ t. VRT en VRM, beslissing nr. 2014/025, 28 mei 2014; Piratenpartij t. VRT, nr. 2014/026, 28 mei 2014

[30] Only public broadcasters, such as the VRT (‘Flemish Radio- & Television’ Broadcaster), publish statistics in this regard; see https://www.vrt.be/nieuws/2016/03/diversiteitscijfers-vrt-tv-meer-vrouwen-en-nieuwe-vlamingen and https://www.rapportannuelrtbf.be/engagements/.

[31] In regards to the audiovisual media services, EPRA has previously surveyed EU countries on their endeavours and targets in relating to the inclusion of the disabled and elderly minority groups. The 2013 report can be found at: https://epra3-production.s3.amazonaws.com/attachments/files/2202/original/accessibility_WG3_final_revised.pdf?1373379195 (03.03.2017)

[32] https://whomakesthenews.org/gmmp/gmmp-reports/gmmp-2015-reports

[33] Eg. MediAcademie, KIK, VAT-exemptions, Postal services, … For more information on potential political influence on the media, please consult: De Keyser J., Journalistieke autonomie in Vlaanderen: onderzoeksrapport in opdracht van het Kabinet van de Vlaamse minister van innovatie, overheidsinvesteringen, media en armoedebestrijding, Gent, Steunpunt Media, 2012, accessible at: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/3039856/file/3039872.pdf (03.03.2017)