Download the report in .pdf

English – German

Authors: Josef Seethaler, Maren Beaufort, Valentina Dopona

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Austria, the CMPF partnered with Josef Seethaler, Maren Beaufort, Valentina Dopona (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Studies), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

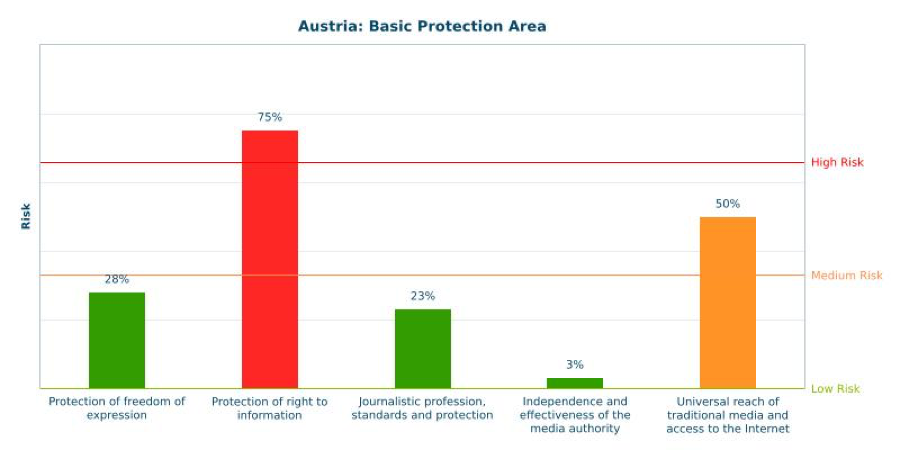

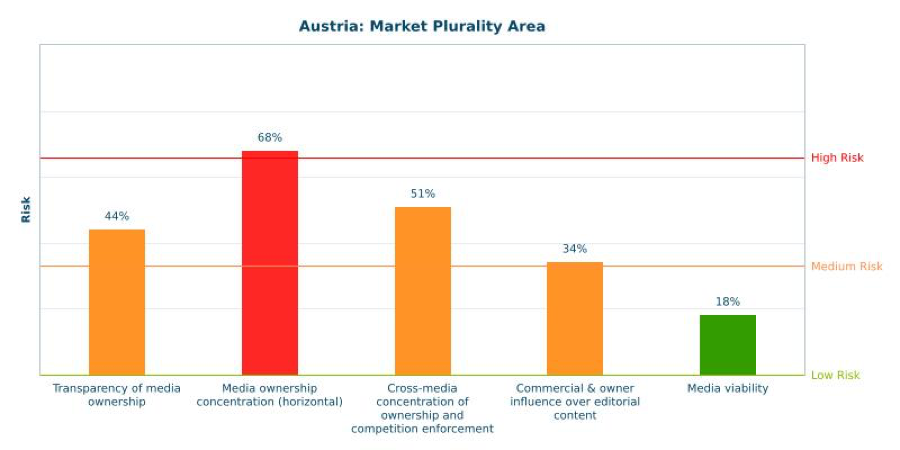

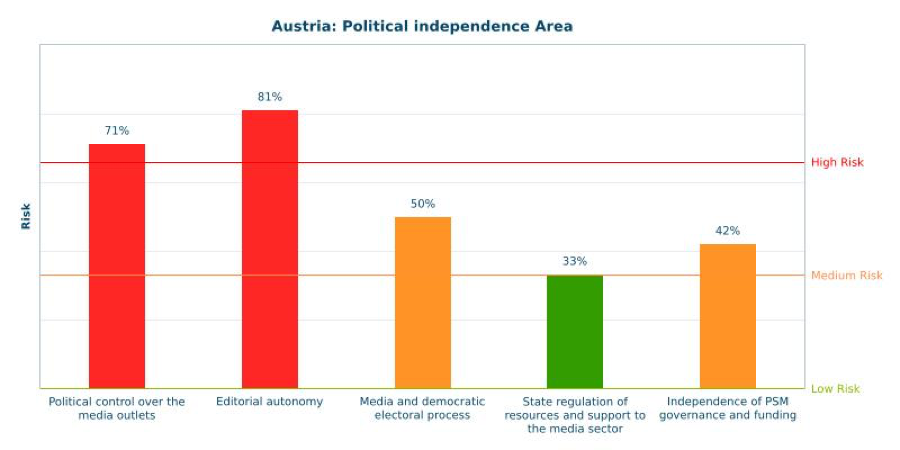

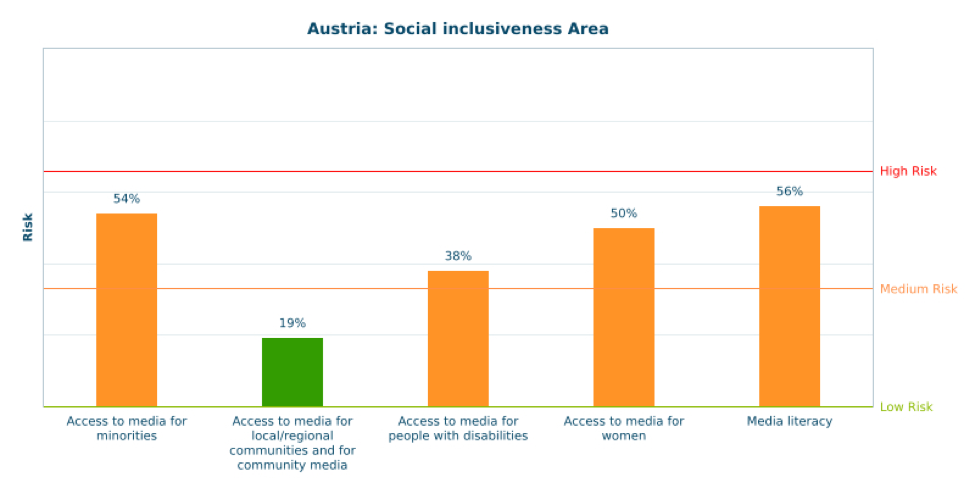

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0 to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk [1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Austria covers an area of 83,878 square kilometres and has a population of 8,700,471 (as of 1 January 2016), including 1,267,674 foreign citizens (14.5% of total population). The largest share is from Germany (176,463), Serbia (116,626), Turkey (116,026), Bosnia and Herzegovina (93,973), Romania (82,949), Croatia (70,248), Hungary (63,550), and Poland (57,589). German is the official language of Austria, and Croatian, Slovenian and Hungarian are recognised as official languages of autonomous population groups in some regions. Overall, Austria can be considered as a socially and culturally relatively homogeneous country.

The Austrian economy grew by 1.0% in 2015. At current prices, the GDP amounted to approximately €339.9 bn (+2.9% in real terms) in 2015 and GDP per inhabitant equalled €39,400. Austria ranks high in terms of GDP not just in the EU, but worldwide. Nevertheless, the unemployment rate was at 5.7% (according to the ILO definition; 9.1% according to the national definition). The youth unemployment rate (15 to 24 years old) was at 6.1%, whereas the unemployment rate of elderly people 55 to 64 years old) was at 4.7%. Non-Austrian citizens were particularly affected by unemployment (11.4%).[2]

All political institutions established by the Constitution (including the Federal President) are voted into office through either direct or indirect elections. Currently, six political parties are represented in the Austrian Parliament. In 2013, the Social Democratic Party received 27% of the vote and 52 seats while the conservative Austrian People’s Party received 24% of the vote and 47 seats. The two parties combined therefore control the majority of the seats. During the last decades, a shift from consociational democracy with its consensus-seeking arrangements to a moderate pluralist party system was observed. With the rise of the Austrian Freedom Party as a right-wing populist party, political culture has become more polarized (Andeweg, De Winter & Müller 2008).

After a long period of relatively stable market conditions, the Austrian media system is currently undergoing profound changes. In the last decade, the dual system of public and private broadcasters, introduced as late as 2001, has led to a decline in the market share of the public service broadcaster ORF and, more recently, to a merger of the two biggest private TV companies, while the growing market share of free daily newspapers has intensified the competition in the newspaper industry. In contrast to the delayed introduction of the dual broadcasting system, new communication technologies have diffused rapidly throughout the country, and the use of online media, particularly of social network services, is rising dramatically, but only the under-25 age group uses social media as one of its primary daily news sources[3]. While television remains the main source of news across all age groups newspapers are traditionally strong among people over 40 years of age. The print media continues to have high circulation figures and is characterised by a small number of large, nationally distributed newspapers and magazines, a few regional newspapers – particularly distributed in the Western and Southern provinces – and a declining degree of horizontal concentration of ownership, although the market remains relatively highly concentrated. At the same time, cross-media concentration is on the rise.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The implementation of the MPM2016 indicates that media pluralism in Austria is at medium risk in all four areas of investigation. Four of 20 indicators represent a high risk, ten a medium risk and six a low risk. Risks to media pluralism in Austria are primarily due to the lack of protection of the right to information, horizontal and cross-media concentration and political control over media outlets as well as lack of transparency in media ownership (but also in the distribution of state advertising to media outlets), commercial influence over editorial content, an enduring political bias in media coverage (particularly during electoral campaigns), threats to the independence of PSM governance and funding, limited social inclusiveness of the media, and missing monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms in several regulations. There are also insufficiencies in broadband coverage.

On the other hand, it has to be emphasized that the very foundations of the democratic media system are intact and strong: freedom of expression is well protected. The viability of the media market is not at risk. Journalism is in many ways legally recognised not a product, but primarily a service. Media authorities work independently and effectively. PSM journalism is strong, but – equally important – there is a rich and varied supply of media services, including a lively community media sector. Broad access to media by regional and local communities supports the idea of a federalist state. Based on these viable foundations, it is up to all stakeholders to remedy the shortcomings and prepare not only for tomorrow’s media infrastructure development, but also, most importantly, for the challenges of a democratic and diverse society.

3.1 Basic Protection (36% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The MPM analysis shows that freedom of expression is well protected in Austria (low risk). Freedom of expression is recognized in Article 13 of the December Constitution of 1867, to which the Austrian Federal Constitution of 1930 refers to in Article 149. Austria ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), protecting freedom of expression in Article 10, in 1958. Since 1964, the Convention is part of the Austrian Constitution, and all restrictions are in accordance with Article 10 of the ECHR. In addition, Austria ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 1978, but regulations on the implementation are still missing. In the event of violations of freedom of expression, a citizen may appeal to the Austrian Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights. Today, the legal remedies against violations of freedom of expression can be considered effective; however, in prior years, the European Court of Human Rights has overturned a considerable number of national courts’ decisions. To date, there have been no serious violations of freedom of expression online. Regarding the sensitive question of criminalisation of defamation, Article 111 of the Austrian Criminal Code allows for an increased prison sentence for defamation and insult (there is a separate ‘insult’ law in addition to libel laws) when defamation has been made accessible to a wider public by means of the mass media, particularly in cases of insult to state symbols. Moreover, Article 6 of the Media Act of 1981 makes the publisher strictly liable. On the other hand, according to a 2015 report by the International Press Institute, there are specific clauses in law protecting journalists from liability as long as they have observed basic journalistic duties (Article 29 of the Media Act of 1981), and Austria is one of only two EU countries that currently provide statutory caps on non-pecuniary damages in defamation cases involving the media.[4]

The MPM results show that the Protection of the right to information is at high risk. Article 20(4) of the Federal Constitution guarantees the right to information. However, the obligation of administrative authorities to maintain secrecy has precedence. In the event that access to information is denied, one only has the right to file a judicial appeal with the Federal Administrative Court in line with the General Administrative Procedures Act. There are no clear procedures (or timelines) in place for dealing with such appeals. In the appeal process, the government does not bear the burden of demonstrating that it did not operate in breach of the rules. Furthermore, those filing an appeal have no right to file an external appeal with an independent administrative oversight body. In line with the high risk score indicated by the MPM2016 analysis, the right to information in Austria was considered the worst among 102 countries in a recent study conducted by Access Info Europe and the Centre for Law and Democracy.[5]

The indicator Journalistic profession, standards and protection is ranked as being at low risk. Access to the profession is free and open. In a corporatist country like Austria, a broad section of journalists is represented by professional associations, but their numbers are declining: from over 85% in the 1970s to less than 50% in the last years. Due to increasing economic pressure, social and job insecurity are on the rise. Freelance journalists in particular, whose numbers are on the rise, are facing uneasy social conditions. There are no cases of attacks to the physical or the digital safety of journalists, but offensive and threatening speech – especially against female journalists – is increasing rapidly.[6] Article 31 of the Media Act of 1981 provides strong protection for the confidentiality of journalists’ sources.

The indicator Independence and effectiveness of national authority is ranked as being at (very) low risk. In 2001, the Austrian Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications (RTR) was established, The RTR provides operational support for the Austrian Communication Authority (KommAustria), the Telekom Control Commission (TKK) and the Post Control Commission (PCK). These are all are separate legal entities fully independent of the government. Appointment procedures are transparent; duties and responsibilities are defined in detail in the law. KommAustria has policy-implementing, decision-making and sanctuary powers. It monitors services operated by licensed operators to assess if they comply with the rules on quotas, advertising and the protection of minors, and holds a number of supervisory tasks, in particular regarding the economic aspects of public service broadcasting. Decisions must be published and can be appealed before the Federal Administrative Court. The RTR is funded by portions of consumer licence fees and contributions from market entities. The organization’s business operations and annual financial statements are reviewed by external auditors. Its transparent work (and independent status) has made KommAustria/RTR highly respected.

The indicator on the Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet shows a medium risk. Public TV and radio signals reach most of Austria’s population. However, broadband coverage is only high in urban areas and the subscription rate is only 77%. The average Internet connection speed is only 13 Mbps. The market share of the Top4 Internet service providers is 88% (all data from 2016).

3.2 Market Plurality (43% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator Transparency of media ownership is ranked as being at medium risk. Media companies are obliged to publish their ownership structures on their website or in records or documents that are accessible to the public, but this information has to be updated only once per year. Media law requires administrative penalties to be imposed on companies that do not disclose information on their ownership structure. Nevertheless, some shareholders and investors as well as the amount of their investment (sometimes when banks are involved) remain – at least somewhat – unknown.

The MPM results show that Media ownership concentration represents a high risk. The legislation for the audiovisual and radio sectors contains specific restrictions regarding areas of distribution in order to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration. However, these restrictions are not so tight because, according to the Private Radio Law and the Private Television Law of 2001, a media company is allowed to own several radio or TV stations if the areas of distribution do not overlap, even if the whole area of Austria is covered by these stations. The market share of the Top4 audiovisual media owners (in terms of the total revenue generated in the audiovisual market) is almost 100% (excluding foreign television stations since no data exclusively concerning the Austrian market is available). There is insufficient information available on the total revenue of all radio owners. Audience concentration for the audiovisual media market is 64% and 85% for the radio market (2015).[7] The market share of the Top4 newspapers owners (in terms of the total revenue generated in the newspaper market) is 85%; readership concentration for the newspaper market is 73% (2015). Although cartel law includes certain rules concerning the plurality of the media, it has been ineffective in preventing mergers of media companies (1988: ‘Mediaprint’; 2001: ‘Formil’-Deal; 2017: merger of ATV and ProSiebenSat.1-Puls 4).

The Concentration of cross-media ownership represents the higher levels of medium risk. In addition to the aforementioned restrictions regarding areas of distribution so as to prevent cross-media concentration, media companies that control more than 30% of the newspaper, magazine or radio market are not allowed to own a TV station. There is no similar regulation in the radio sector, thus opening the door for (almost all) Austrian provincial newspaper publishers to acquire regional and local radio stations. There is therefore an increasing degree of cross-ownership in the radio and newspaper sector. The market share of the Top4 owners across different media markets is 62% (this percentage is based on data on the 18 biggest Austrian media companies [data from 2015]). The market share of the Top4 Internet content providers is 68% (2012); the audience concentration for the Top4 Internet content providers is 51% (based on data for unique audiences of the Top10 Internet content providers [data from 2016]).

The indicator Commercial & owner influence over editorial content shows a medium risk. Several media laws contain rules that prevent the use of advertorials and stipulate that the exercise of the journalistic profession is incompatible with activities in the field of advertising. KommAustria (the Austrian communication authority) monitors the advertising activities of TV and radio stations. Moreover, it is stated in the Journalistic Code of Ethics that the economic interests of the owner of the media company should not influence editorial work. However, there are no explicit regulatory safeguards stating that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief have to be made independently of the commercial interests of media organizations. According to the results of a recent survey, almost 10% of Austrian journalists (particularly those who work for private radio and TV stations and weekly magazines) reported influence from the owners of the news organizations, profit expectations and advertising considerations.[8]

According to the data available, Media viability is at low risk. Revenue in the audiovisual sector as well as gross online advertising expenditure increased over the past two years as did the number of individuals who regularly use the Internet and, particularly, mobile devices to access Internet on the move. Austria has a well-established system of state subsidies. Regarding the printed press, the Press Subsidies Act of 2004 provides special subsidies for the preservation of diversity in regional daily newspapers in addition to distribution subsidies for newspapers and grants for journalists’ training. However, the amount of press subsidies as a share of the GNP is decreasing. There are also subsidies for private television and radio stations as well as for community media (with the latter receiving the least funding). Moreover, there are subsidies for digitalization available.

3.3 Political Independence (55% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicator on Political control over media outlets represents a high risk (71%). The Austrian PSM act stipulates independence from political parties, political and economic lobbies, and other politically involved entities as a right of the PSM as well as an obligation. There is no legislation in place in other media sectors that regulates ownership matters regarding owners’ entanglement with the political realm. However, there is no TV or radio station owned and/or controlled by a specific political group, and the share of newspapers owned by politically affiliated entities is below 0.5%. Regarding the PSM, experts criticise the lack of clear independence from political entities, which is likely to create conflict in the company’s management (nevertheless, PSM journalism is considered to be of relatively high quality; c.f. Seethaler 2015). Regarding commercial media (particularly print media), experts argue that mutual influence between politics and media is especially evident in a kind of barter deal in which advertisement investments are traded for favourable reporting. In spite of the 2012 Media Transparency Law, there is no reliable data on the extent to which the state contributes to the TV, radio and newspaper advertising market. Accordingly, there is public discussion about questionable practices in state advertising because advertising orders are mainly given to a few important media outlets, but are not distributed amongst all media outlets (proportionally to their audience shares). From a democratic point of view, this seems to be problematic because editorial autonomy is considered to be a prerequisite to a functioning media system. The Austrian Press Agency (APA), which is owned by 15 Austrian newspapers and the ORF, is independent of political groups in terms of ownership, the affiliation of key personnel, and editorial policy. It is therefore highly respected. Moreover, the leading media distribution networks work largely independently of political group.

Editorial autonomy is at high risk (81%). As this indicator aims to assess whether the regulatory safeguards that guarantee editorial independence are effectively implemented in practice, it first has to be noted that no common regulatory safeguards are in place that guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief. Secondly, only TV and radio stations are obliged to have editorial statutes that guarantee editorial independence. All other media are allowed, but not required, to establish editorial statutes. Thus it comes as no surprise that the three largest newspapers (‘Kronen Zeitung’, ‘Heute’, ‘Österreich’) refrain from self-regulatory measures, and are not members of the Austrian Press Council. These three newspapers are the main beneficiaries of state advertising spending (which is usually considered to be a means to influence media content).

The indicator Media and democratic electoral process is at medium risk (50%). The PSM in Austria is obliged by law to cover political matters in an unbiased and impartial manner. In practice, coverage of all (relevant) political entities is assessed by the APA via their subgroup MediaWatch and the three most important evening news programmes are included in the assessment. Data for the last national election year (2013) indicates that there was a disproportionate amount of coverage of (directly quoted) political representatives with regard to parties’ proportional representation in parliament in favour of the governmental parties. This balances out somewhat during the campaign period.[9] No obligation of fair, balanced and impartial reporting is mentioned in the Code of Ethics for the Austrian Press. In fact, long-term content analysis provides evidence of some bias in election news in newspapers and commercial channels (Seethaler & Melischek 2014). Since 2002, political advertising in PSM has not been allowed during election campaigns. Political advertising may only be bought from private stations. Media companies are urged to provide all parties with equal conditions for advertising because of Article 7 of the Federal Constitution, which refers to the principle of equal opportunities for all political parties, but no measures guaranteeing equal conditions and rates of payment are implemented in media law.

The indicator State regulation of resources and support of the media sector shows a low risk (33%). The practice of spectrum allocation in Austria is codified in Article 54 of the Telecommunication Act and guarantees impartial, transparent and non-discriminatory spectrum allocation in accordance with EU requirements. The distribution of media subsidies is conducted by the Austrian media authority KommAustria. Regarding press subsidies, KommAustria is complemented by the Press Subsidy Committee, which consists of six members, two of which are appointed by the federal chancellor, two more by the Association of Austrian Newspapers (VÖZ), and the remaining two by the journalist labour union. Appointments last for two years. The members are required to settle on a chairperson that is not associated with any businesses in the newspaper sector. The rules for the distribution of direct and indirect subsidies (e.g. tax reductions, reduced train service and telephone rates, favourable conditions for credits) can be considered to be fair and transparent. However, experts criticise the effectiveness of the rules in terms of ensuring media plurality. Unfortunately, the 2012 Media Transparency Law, which forces the government, public bodies and state-owned corporations to disclose their relations with the media (such as advertisements and other kinds of support), does not provide rules on a fair distribution of state advertising to media outlets.

The Independence of PSM governance and funding is ranked as being at medium risk (42%). PSM law provides fair, objective and transparent appointment procedures for the management and board functions, and politicians are not allowed to act as leading figures of the ORF or its Foundation Council [Stiftungsrat]. However, 15 of the 35 members of this council (which appoints all high officials, approves the budget and controls financial activities) are appointed by the federal government, six of which are appointed with respect to the proportional strength of political parties represented in parliament. Moreover, each of the nine Austrian provinces nominates a representative. Procedures may be considered to be monitored and safeguarded, but, in practice, they are strongly impacted by political entities. This became particularly apparent in August 2016, when the Director General had to be elected.[10] Regarding the funding of PSM, it has to be noted that provincial governors are allowed to use some license fee revenue for purposes other than their intended use (e.g. for financing old town preservation, music schools and hospitals; c.f. Fidler 2017).

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (43% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator Access to media for minorities is ranked as being at medium risk (54%). PSM law guarantees the representation of the six legally recognised minority groups (‘autochthonous groups’, based on the 2001 census) by requiring an ‘appropriate’ share of airtime. However, it does not provide any framework for the assessment of ‘appropriateness’. Accordingly, the ORF Public Value Report from 2015/16 reports on the provision of 13 different radio programmes devoted to the six minority groups, adding up to an average of 6.6 broadcasts per week in the respective native language.[11] (However, the ORF purchases some programmes or parts of programmes from community radio broadcasters.) Additionally, the public broadcaster provides one programme on TV per a week (entitled ‘Heimat, fremde Heimat [Homeland, Foreign Homeland]’). Thus, the legally recognised minorities have reasonable access to airtime but this does not apply to minorities not recognised by the law (e.g. Turks, Serbs, Bosnians, etc.). Private commercial television and radio stations do not provide airtime to minorities. Fortunately, Austria has one significant non-commercial TV station (OKTO) that devotes airtime to minorities and hosts the Latin American channel Latino TV, the African channel Radio Afrika TV and the Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian programme Dijaspora Uzivo. Two further TV stations are devoted to minorities (the Bosnian satellite station TV Pink Plus and the Turkish community’s, YOL Medien AG), and Austria has a rather well-developed network of community radio broadcasters that dedicate (parts or all of) their programmes to minorities. In 2014/15, M-Media, an association that supports intercultural media (www.m-media.or.at), reported about 67 print newspapers that are devoted to a specific ethnic or minority group. Furthermore, 23 online news websites and 12 newspapers (online and offline) can be considered to be cross-community media. However, the majority of these newspapers is not published on a daily basis. No data on their circulation and reach is available. Considering that non-Austrian citizens make up 14.6% of the total Austrian population, more should be done to safeguard proportional access to media for minorities.

The indicator Access to media for local and regional communities and for community media is ranked as being at low risk (19%). This is because (1) the law grants regional and local media access to media platforms, and access to radio and TV frequencies is regulated via public tendering, (2) subsidies for private radio and television companies are explicitly contingent upon the provision of local/regional programmes, (3) the public broadcaster operates regional broadcasting studios in all nine federal states that provide nine regionally broadcast radio programmes and TV newscasts. However, Austrian broadcasting laws are still lacking a consistent legal recognition of community media as third media sector in terms of function, mode of operation and financing, albeit community media performs a wide range of socially relevant functions (Beaufort & Seethaler 2017). Subsequently, Austrian media law does not provide sufficient details regarding licensing processes and criteria concerning community media. Especially when it comes to the implementation of digital terrestrial broadcasting via DAB+ (which suits mass media broadcasters with a strong financial back bone), there is no sufficient concept of addressing potential discrimination of non-commercial media due to the lack of financial means that are needed to participate. The Austrian media authorities KommAustria and RTR manage a (not so well remunerated) promotion fund for non-commercial local radio and TV broadcasters, but particular quality standards that apply to the specific functions of community media (such as fostering active volunteer participation in media production as well as engagement in civic society; c.f. European Parliament 2008) are practically of minor relevance. Independence from governmental, commercial and religious institutions and political parties is one of the eligibility criteria for receiving subsidies; and both the Association of Community Radios and the Alliance Community Television Austria have developed appropriate codes of conduct.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities represents a medium risk (38%). The Austrian public service media is required by law to provide access to media content (including on-demand media content) for disabled people in accordance with current technology as far as economically reasonable. Despite the fact that the legal text is non-committal in its wording, the ORF has decided to continuously increase the share of programmes with additional features for people with disabilities. Nevertheless, there is a strong imbalance between the extent of media access for hearing-impaired people (which is rather well developed) and for visually impaired people (which is rather poorly developed). According to the ORF 2015 Annual Report, almost 68% of the programmes on the two main national TV stations was available with subtitles and 986 hours of programming were broadcast via teletext, whereas only 1,054 hours of programming were provided with audio description (which is equivalent to approximately three hours of airtime per day).[12] Unfortunately, the Audiovisual Media Law concerning private television stations simply states that providers are obliged to incrementally improve accessibility for people with disabilities without stipulating specific requirements and actions to achieve this goal. Accordingly, the two largest private broadcasters (ATV and PULS 4) do not provide any services for hearing- or visually impaired people

The indicator Access to media for women is also ranked as being at medium risk (50%). Generally, the Austrian Equal Rights Act does provide a framework to ensure equal rights in employment matters. It also provides a number of sanctions as well as mechanisms to enforce the law; however, a complaint must be filed before action is taken. Moreover, there are no sufficient legal requirements in place for setting up monitoring bodies. In the area of media law, only the ORF Act provides a more explicit framework for the equal rights of employees and for monitoring practices such as a gender mainstreaming plan. The ORF Public Value Report from 2015/16 shows that women make up 43.2% of all personnel.[13] Although PSM law provides a legal threshold for the desired share of women working at the PSM (45%), this rule does not apply to the management board. Regarding the programming content, the ORF Act rather vaguely demands a policy regarding equal rights of several groups such as women, disabled persons, recognised religious groups, etc. According to the 2015 Annual Report of the Global Media Monitoring Project[14], women account for 21% of all people who appear in news stories as subjects or sources from traditional media (print, radio and television) and for 16% online. An Austrian study using a similar methodology and based on a representative sample of more than 20,000 media reports in 2014 reveals even lower percentages for traditional media (14.4%) and slightly higher percentages for online media (17.9%; c.f. Seethaler 2015).

Media literacy is ranked as medium risk (56%). There are many initiatives that foster media literacy competence among young people and aim at improving media education (they are mainly sponsored and/or hosted by the Federal Ministry of Education), but a comprehensive governmental strategy is missing. Although media literacy is present in the curriculum of primary and secondary schools, there are some shortcomings. Firstly, teacher training is lagging behind, and secondly, media literacy is not among the primary concerns of the school administrators.. In a first important step, in autumn 2016, the module ‘Communication and Media’ became an obligatory part of the school subject ‘Political Education’, which itself will become obligatory for all students from the 8th year onwards. The Austrian Federal Ministry of Education has launched several initiatives to promote media literacy among young Austrian citizens. Among them are the ‘Grundsatzerlass Medienerziehung’, a decree for media education that aims at meeting media requirements in educational contexts; the Media Literacy Award for the best and most innovative educational media projects in schools; the magazine ‘Medienimpulse’, which is published four times a year; the online platform mediamanual.at, which provides materials, suggestions and content for theoretical and practical media education; and the ‘Media Literacy Week’, which will take place for the first time ever in 2017. Moreover, strategies for safe Internet use have been developed (saferinternet.at). There are also several initiatives by media organizations (such as the PSM ORF and the Austrian Newspaper Association) and civil society groups (such as the Democracy Centre). Most of these initiatives are aimed at young people, while recurrent and lifelong learning remains an even greater challenge to Austrian media and education policy. According to Eurostat data, 75% of Austrians that have used the Internet in the past three months have at least basic skills in using digital technology and 80% have at least basic digital communication skills.

4. Conclusions

In all four areas of the Monitor, the indicators analysed indicate that media pluralism in Austria is at medium risk. These results could be interpreted as challenges to media policy.

After comparing the quality of laws on the right to information (RTI), Access Info Europe (AIE) and the Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD) ranked Austria last of 102 countries worldwide. Presently, the relevant law regulates the right to apply for information, but it does not guarantee a general right of access. Hence, state bodies can refuse to provide information without having to justify their decision. To address this legislative gap, the Council of Europe has recommended that Austria develop precise criteria for a limited number of situations in which access to information can be denied, and ensure that such denials can be challenged (Council of Europe 2012). Based on these findings as well as the MPM2016 analysis, the authors recommend that the government improve the RTI law. Furthermore, a lot of the data considered as necessary to carry out the Monitor assessment is not easily available to the public in Austria. This includes data on cross-media concentration and the share of state’s contribution to the advertising spending of particular media companies. The authors suggest that the government addresses this lack of transparency, first, by imposing information duties on the entities in the various sectors, second, by guaranteeing information rights and supporting research on these matters.

In recent years, the Austrian media system has become more diverse and concentration among the various media markets is declining (although it remains at a relatively high level). However, some regulations in private radio law and private television law foster cross-media concentration. Moreover, little is known about the possible impact of political or commercial entities (particularly banks) on editorial autonomy and media content, for example through the allocation of advertising and attempts to influence the appointment procedures for management and editorial functions in media organisations. Self-regulatory measures (like editorial statutes) that stipulate editorial independence and foster internal plurality should therefore be obligatory for all media companies.

In general, the authors suggest more effective monitoring compliance with the existing rules in media governance regarding, for example, appointment procedures at ORF, the transparency of ownership and financing, and access to airtime for different social groups. Particularly, measures should be developed to improve both the representation of women in management boards of media companies, newsrooms and the news, as well as the legal environment for the development and functioning of minority media. The authors feel ashamed that the latter has to be written in a country located in the heart of Europe in the year 2016.

In regard to supporting community media, more could be done, particularly when considering the level of subsidies given to commercial broadcasters. More government support is imperative because openness to the idea of community members participating in the creation of media content will be a highly important topic in future media production. In addition to increasing financial support, it seems very important that the authorities fully commit to community media as a media sector of its own, characterized by quality standards that are in accordance with its conceptual conditions. Community media expertise should also be available within the structure of the RTR and KommAustria (both of which are regarded as highly respected authorities because of their independent and quality work).

There are many initiatives that foster media literacy competence among young people (they are mainly sponsored and/or hosted by the Federal Ministry of Education), but a comprehensive governmental strategy is missing. Above all, more comprehensive political efforts are needed to really establish media (and advertising!) literacy as a key component of mandatory school curriculum for all children and schools. In the area of lifelong learning, recent research with adults has shown that public service announcements which raise awareness towards the role of journalists in news production are effective in helping people see themselves as news media literate and able to participate in the political process.

References

Andeweg, R B, De Winter, L & Müller, W C 2008, “Parliamentary Opposition in Post-Consociational Democracies: Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands, in The Journal of Legislative Studies, 14(1-2): 77–112. DOI: 10.1080/13572330801921034

Beaufort, B & Seethaler, J 2017, “Zwischen Objektivität und Perspektivität: Österreichs Journalismus auf der Suche nach neuen Vermittlungsformen [Between Objectivity and Interpretation: Austrian Journalism and New Media Formats]”, in Was bleibt vom Wandel? Journalismus zwischen ökonomischen Zwängen und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung, edited by S. Kirchhoff, D. Prandner, I. Aichberger & G. Götzenbrucker. Baden-Baden: Nomos, forthcoming.

Council of Europe 2012. Joint First and Second Evaluation Round Addendum to the Compliance Report on Austria Adopted by Council of Europe Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) at its 56th Plenary Meeting (Strasbourg, 20-22 June 2012).

European Parliament 2008. Report on Community Media in Europe (Brussels, 24 June 2008).

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+REPORT+A6-2008-0263+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

Fidler, H 2017, Österreichs Medien und ihre Macher [Austrian Media and ist Producers]. www.diemedien.at

Lohmann, M I & Seethaler, J 2017, “Medienkonzentration in Österreich im 21. Jahrhundert [Media Concentration in Austria in the 21st Century]”, in Media Perspektiven, forthcoming.

Seethaler, J 2015, Qualität des tagesaktuellen Informationsangebots in den österreichischen Medien: Eine crossmediale Untersuchung [News Quality in Austrian Media: A Cross-Media Comparison]. Wien: RTR.

Seethaler, J & Melischek, G 2014, “Phases of mediatization: Empirical evidence from Austrian election campaigns since 1970”, in Journalism Practice, 8(3): 258–278. DOI:10.1080/17512786.2014.889443

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Josef | Seethaler | Dr.; Deputy Director | Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Studies | X |

| Maren | Beaufort | MA; Junior Scientist | Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Studies | |

| Valentina | Dopona | BA; Master Student | Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Studies |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Walter | Berka | Prof. Dr. | University of Salzburg |

| Alexandra | Föderl-Schmid | Dr. | Editor in Chief, “Der Standard”; IPI |

| Alfred | Grinschgl | Dr. | Austrian Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications (RTR) |

| Dieter | Henrich | Mag. | Verband der Regionalmedien Österreichs |

| Daniela | Kraus | Dr. | forum journalismus und medien (fjum) |

| Helga | Schwarzwald | Dr. | Association of Community Radios |

| Christian | Steininger | Prof. Dr. | University of Vienna |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Statistics Austria (https://www.statistik-austria.at)

[3] Eurobarometer 84.3 (November 2015)

[4] https://legaldb.freemedia.at/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IPI-OutofBalance-Final-Jan2015.pdf

[5] https://www.rti-rating.org/

[6] https://www.falter.at/archiv/wp/uns-reichts

[7] All data on market shares and concentration rates mentioned in this paper is based on Lohmann & Seethaler 2017.

[8] www.worldsofjournalism.org

[9] https://derstandard.at/1385171877383/Zweidrittelmehrheit-fuer-SPOe-und-OeVP

[10] See, for example: https://derstandard.at/2000044450567/ORF-Personalia-sorgen-fuer-schwere-Koalitionskrise?ref=rec; https://diepresse.com/home/kultur/medien/5086459/ORFDirektorenwahl-fur-Redakteure-unwurdiges-Schauspiel?from=suche.intern.portal

[11] https://zukunft.orf.at/show_content.php?sid=147&pvi_id=1688&pvi_medientyp=t&oti_tag=PVB 15/16

[12] https://zukunft.orf.at/rte/upload/texte/2016/jahresbericht_2015.pdf

[13] https://zukunft.orf.at/show_content.php?sid=147&pvi_id=1688&pvi_medientyp=t&oti_tag=PVB 15/16

[14] https://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/national/Austria.pdf