Katarzyna Vanevska, Jagiellonian University, Institute of Journalism, Media and Social Communication

Context

Polish policymakers, as well as the public, seem to overlook the problem of “news deserts”, which until recently remained completely unrecognised. In response to the wave of bankruptcies and closures of local independent media, some civil society initiatives have been launched to identify them. In order to list this type of media and develop current maps of their coverage a call for applications was announced in the first weeks of 2023.[1] Apart from this project, led by Katarzyna Batko-Tołuć, the concept of “information deserts” is not included in Polish media legislation or the industry debate.

The map developed in the above-mentioned project shows regions where there are “news deserts”. In many areas of the country there are places where not a single type of independent media applied for the project, which can be interpreted as their complete absence. Interviews and analysis conducted as part of the LM4D project confirm the above data.

An important problem in the context of “news deserts” in Poland is that in many regions the only local media are local government media, most often at the service of politicians holding power in the region. These media belong to local government authorities (municipalities, counties, voivodeships), are financed by these local governments and are subject to their control and influence. Therefore, the local media function in these areas, but it cannot be said that it performs its basic functions, such as scrutinising local authorities or providing reliable information for the audience.

The definition of a local broadcaster does not exist in the Polish legal system[2], nor a local media definition. However, the national regulatory body, the National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT), according to the position on 10 June 2008, has qualified for broadcast on local issues topics such as: current events and problems concerning the local community; culture and history of a given region; useful local information.[3] There is no definition of community media in media law, while there are many ambiguous, often misleading terms referring to this sector.

In media law exists the concept of community broadcaster (exempt from license fees, cannot broadcast advertising). However, this option is so unattractive that currently this role is performed by only nine broadcasters. All entities are church media.[4]

[1] K. Batko-Tołuć, Pustynie medialne – media niezależne, 2023, https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1KbrxGyPQSJ5RLB9eWnKEa3FRFIjSpd8&ll=52.87803907871886%2C20.229565266399156&z=7

[2] KRRiT, Response to the request for access to public information issued by the researcher, dated 25 May 2023, 2023.

[3] M. Kornacka-Grzonka, Media lokalne Śląska Cieszyńskiego. Historia i współczesność, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, Katowice, 2019.

[4] Krajowa Radia Radiofonii i Telewizji. Wykaz nadawców społecznych (stan na dzień 30 września 2021 r.), 2021, https://www.gov.pl/web/krrit/nadawcy-spoleczni

Main findings

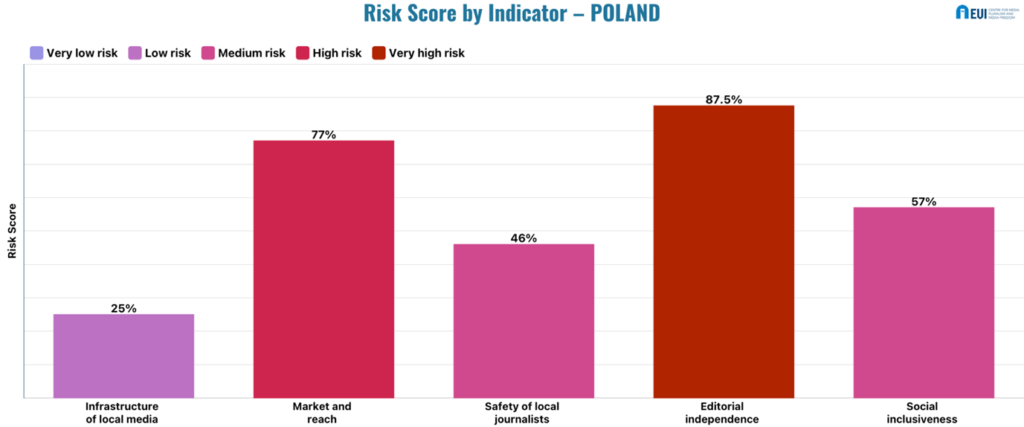

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Low risk (25%)

The local press in Poland is most often published in the main cities of the poviats[1] to which individual rural areas belong. Media consumers using the paper edition of the local weekly regularly, are mainly inhabitants of villages (28.3%) and towns with a population of up to 50,000 (21.7%).[2] Internet penetration in rural areas is systematically increasing.[3]

Local press titles are also published in small communes with a population of several thousand people, but the distribution and reach of the editorial offices are diverse and impossible to systematise. This is especially because there is also a group of publishers in Poland that are not affiliated at all, making it difficult to find them and recognise the reach of their media.

The data of the “Civic Network” show that about 58% of municipal governments run their own print media outlets. This is valid for 80% of local governments, counting for about 1,160 press titles.[4]

There are 118 independent local radio stations in Poland, according to a 2021 KRRiT report. Unfortunately, their area of influence can be considered small, as they cover only 18.75% of the country.[5]According to the same report, local community radio only covers 3.5% of the country, local government radio 3.67%, academic radio 1.26%. The situation is different for so-called “socio-religious” radios, such as Radio Maryja and Radio Plus. Their range covers almost the whole country very thoroughly.[6] The range of groups of individual radio stations is quite limited, but the combined range of local stations of Eurozet, Agora, RMF and ZPR Media cover the whole country, including rural areas, except for the Warmian-Masurian and Kuyavian-Pomeranian voivodeships.

Regional branches of public service media—TVP and Polish Radio—cover well the whole country. In the case of Polish Radio’s regional stations, the north and north-east of the country are a relatively “empty” places. Population coverage of Polish Radio regional programmes comes to 36,969 thousand people.[7]

The KRRiT granted 166 licences for programmes broadcasted on cable networks, and two licences are used to provide local programmes distributed in local multiplexes.[8] This number is changing, but in recent years a downward trend is observed.[9] Virtually all local broadcasters broadcast their programmes on cable networks, which are trying to expand their reach.

In the largest Polish metropolises, apart from a few exceptions, there are no publishers of independent local press and local information portals. City dwellers can therefore draw information almost exclusively from the local titles of Polska Press, which belongs to the State Treasury Company PKN Orlen. In 2021, the number of local weeklies published by Polska Press fell to 94, and 2022 brought further closures (it is estimated that over 30 titles were liquidated. Polska Press also publishes 23 regional information services and has 109 editorial offices in Poland. Its publications are therefore widely available in cities, but they are largely influenced by political propaganda.

[1] The local self-government community (all inhabitants) and the appropriate territory, i.e. a unit of basic territorial division covering the area of several to a dozen or so communes or the entire area of a city with poviat rights (i.e. a commune with city status that has been granted poviat rights). GUS, https://stat.gov.pl/metainformacje/slownik-pojec/pojecia-stosowane-w-statystyce-publicznej/811,pojecie.html

[2] Stowarzyszenie Mediów Lokalnych. Stan i kierunki rozwoju mediów zrzeszonych w Stowarzyszeniu Mediów Lokalnych oraz wybranych mediów lokalnych w Polsce, 2022.

[3] IAB Polska. RAPORT STRATEGICZNY Internet 2021/2022, 2022, https://raportstrategiczny.iab.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Raport-Strategiczny-2022.pdf

[4] Sieć obywatelska. Watchdog., Fundacja Wolności, Media lokalne jako warunek zapewnienia praworządności na poziomie lokalnym. Jak budować ich odporność?,2023.

[5] KRRiT. Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z działalności w 2020 roku, 2021, https://www.gov.pl/web/krrit/sprawozdanie-z-dzialalnosci-krrit-za-2020-rok

[6] KRRiT. Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z działalności w 2022 roku. 2023, https://www.gov.pl/web/krrit/krrit-przedstawila-sprawozdanie-z-dzialalnosci-w-2022-r

[7] KRRiT. Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z działalności w 2020 roku, 2021, https://www.gov.pl/web/krrit/sprawozdanie-z-dzialalnosci-krrit-za-2020-rok

[8] KRRiT. Response to the request for access to public information issued by the researcher, dated 25 May 2023, 2023

[9] P. Różycki, Member of the Management Board of TV ASTA, 5 October 2023, phone interview.

Market and reach – High risk (77%)

Data on local media market revenues are dispersed and only preliminary conclusions can be drawn based on partial sources.Local media in Poland have been facing increasing difficulties in recent years, worsened by financial problems after the pandemic: closed points of sale, a decrease in the number of advertisements or payment backlogs.[1] There is no systemic financial and legislative support for them. This was fundamental for establishing a new order in the local newspaper market, because the German Verlagsgruppe Passau, hit by advertising revenue losses, agreed to sell the Polska Presse Group to the state-owned oil company Orlen in December 2020. Thus, a kind of nationalisation of many local editorial offices took place and, consequently, led to an increase in political media influence.

Basic problems are the drastic increase in costs and liquidation of distribution points for paper press.

The main difficulties for local media include factors such as the war in Ukraine and related inflation, rising energy and paper costs, but also labour shortages, and a structural decline in advertising revenues. The digital transformation and shift of readers online is also very significant. The greatest threat to local digital media has turned out to be municipal media, which also have a devastating impact on the local printed press sector. According to experts, this necessitates a public debate and legal clarification of how local governments should spend their money on promotion. Local government media are financed by local institutions directly and indirectly (e.g. local government employees write articles for them), while pretending to be independent and entering into unfair competition with local independent media.

Local independent publishers are struggling to maintain their position in the market, develop subscriptions, invest in digital tools and gain new users online, but the market shows that recipients are generally not willing to pay for local news. In Poland, there are practically no examples of large sales of local media with the help of a paywall or crowdfunding.

Local radio stations are also falling into crisis, which in their case is dictated, among other things, by a drastic increase in energy prices, even by 300%. Many stations, including those with a long tradition, had to stop broadcasting.

The pandemic has ultimately disrupted the local TV business model, leading to a 30 to 50% decline in advertising revenue across various local TV stations. Experts agree that the financial situation of local television stations can be described as “a state before agony”; many survive only because, in addition to their media activities, they generate income, e.g. from filming weddings[2] In recent years the number of cable operators offering a local TV station has also decreased.[3]

One challenge is also represented by the arbitrary allocation of state or public entities’ advertising. Media financial independence and press pluralism are described in the press law but not implemented in practice.

[1] P. Piotrowicz, president of the management board of the Local Media Association. 10 May 2023, online interview.

[2] K. Pstrong, Director General of the Polish Chamber of Electronic Communications, 10 October 2023, phone interview.

[3] P. Różycki, Member of the Management Board of TV ASTA, 5 October 20203, phone interview.

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (46%)

The vast majority of local journalists experience financial difficulties, face a lack of professional stability in the case of independent media, or need to accept political pressure in media related to the state or local government.

Many journalists work on mandate contracts and contracts for specific work, which provide almost no social benefits. Contracts of employment (with full social care) were used mainly for the oldest titles on the market, but this is changing, as publishers are trying to bind journalists with their media.

Freelance work is done mostly on the basis of self-employment or two types of contracts: a contract for a specific task and a mandate contract. Depending on the contract chosen, income varies greatly (e.g. paying social security contributions on their own). The last two forms are the so-called junk contracts and for many journalists these turned out to be particularly unattractive during the pandemic, which significantly limited their possibilities of professional activity while not providing any social support.

Local journalists, regardless of the type of employment, face the challenges of multitasking and the implementation of a whole range of editorial tasks by one person or a team reduced to a minimum. Earnings depend on the editorial office. There is no hard data. From publishers’ reports, it seems that they are closer to the minimum wage than the national average.[1]

Publishers pointed to the low availability of journalists on the labour market, especially in smaller cities, the unsatisfactory preparation of graduates in the profession, and the ageing of journalism. Local media themselves prepare people for journalistic work, who usually come from other professions. Publishers notice that the profession of journalism has lost its prestige in society’s eyes.[2]

The situation of journalists of local titles from Polska Press after its takeover by Orlen turned out to be particularly difficult, finding themselves in the face of political influence. Working conditions in local government media are a separate issue because in large part these media are not composed of journalists at all, but of local government officials.

Representatives of local media interviewed by a researcher report that they have not encountered physical attacks on local journalists, while as for online attacks, they are common, but they are not much of a hindrance to work. Journalists add that they are often victims of hate speech and have to deal with it on a daily basis.

A serious problem for local journalists are lawsuits, which are, even if they do not result in a court verdict, unfavourable to publishers and editors, because they still effectively engage their time and money resulting in chilling effects on their work. SLAPP cases are severely underestimated for several reasons: a lack of awareness that a pending case may be a SLAPP case and the reluctance of journalists to inform the public about having such a problem. An equally great threat to local media are private accusations of defamation, under Art. 212 of the Criminal Code. Poland regularly loses cases under Art. 212 before the European Court of Human Rights.

The Association of Polish Journalists and the Association of Journalists of the Republic of Poland are the largest organisations and gather mainly national media journalists, but also have regional branches. However, experts point out that none of them operate effectively at the local level, where two associations are currently the most important: the Association of Local Newspapers and the Association of Local Media. Expert states that journalistic organisations have minimal impact on the editorial independence of journalists[3], which depends primarily on the editorial staff. Media concentrated in the two organisations mentioned above focus on control functions, so must pay attention to independence and professionalism.

[1] A. Andrysiak, president of the Association of Local Newspapers, May 2023, email and phone interview.

[2] Stowarzyszenie Mediów Lokalnych. Stan i kierunki rozwoju mediów zrzeszonych w Stowarzyszeniu Mediów Lokalnych oraz wybranych mediów lokalnych w Polsce, 2022.

[3] P. Piotrowicz, president of the management board of the Local Media Association, 10 May 2023, online interview.

Editorial independence – Very high risk (87.5%)

The indicator editorial independence scores a very high risk of 87.5%, representing the highest risk score across all the indicators under analysis.

In Poland, relevant legislation lacks regulatory safeguards to limit political control over the media through ownership. In these terms, an alarming element is the activity of Polska Press, which brings together a significant part of regional titles. It was bought by a state-owned company and key decisions are made from a political and not business point of view, which means, for example, personnel exchange in the acquired media or the issuing of central instructions regarding the editorial line. Daniel Obajtek, President of PKN Orlen, is a man so closely associated with the ruling party that he was even tipped to be prime minister. Immediately after taking over the media company, he introduced Dorota Kania—a journalist who positively highlights the actions of the authorities—to its management board.

Moreover, one of the most pressing problems on the Polish local media market in terms of political influence is that, according to various estimates, more than 55% to 60% of Polish communes run press (paper and online versions) that pretend to be part of the local media market. These are publications that are fully controlled by the authorities issuing them and which do not offer reliable information. At the same time, great care is taken to distribute such information, which is easily accessible and free. This destructive activity has already been indicated by The Ombudsman, the complaint was also sent to the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights.[1]

The first tool of political pressure on local media is money, and the unfair and non-transparent allocation of state subsidies and state advertising have become an everyday occurrence.

State advertising is not allocated to independent local media. Specialists and journalists of independent local media agree that they have not encountered such government support (in any sector).

Funds awarded through the National Institute of Freedom (state subsidies) are granted for the outlets close to the ruling party. The rules and procedures for granting them are unclear, unreliable and non-objective. Government subsidies granted to the media under the Government Program for the Development of Civic Organizations PROO are, to a large extent, granted for the media run by politicians of the ruling Law and Justice party. On the other hand, professional media at the local or regional level are supported on a discretionary basis – both by the government and local government.[2] The situation of local PSMs is unique, as well as Catholic media, including, above all, radio Maryja and TV Trwam, which are intensively supported by the state (subsidies and advertising).

Moreover, as local journalists emphasise, close relationships in local communities do not facilitate independence; for example, one can take advantage of the situation of other people in the family (e.g. local authorities influencing the employment of family members, their working conditions in offices or local companies). There are also attempts to solicit / bribe journalists from independent media, offering them work in promotion departments or in newspapers run by local governments.

In terms of commercial influence over editorial content, sponsored materials are marked in a non-transparent way, especially when it comes to websites. The Media Ethics Council (REM) indicates that surreptitious advertising appears more often, because of the difficult financial situation of the media. In order to survive, they must publish, apart from advertising, paid texts, expressing only the views of those who finance them.[3]

The National Broadcasting Council does not have local branches, but its statutory competence does cover matters relating to audio-visual, local media, including broadcasters of local radio and television programmes, operating both in the private (commercial) and public sectors. The Council’s ability to fulfil its constitutional mission has been limited by the policy of the Law and Justice party, which deprived the National Council of influence on the management and supervisory boards of public media companies (TVP and Polskie Radio), as well as on the content of the articles of association of these companies.[4]

The specific takeover of public media by the former ruling party had an impact on the situation of the regional branches of both TVP and Polish Radio. Shortly after the 2015 elections, layoffs of local public media journalists began. Government has systematically taken over the public media, “filling with its people” all important positions in the organisational structure of the public broadcaster, leading to internal censorship and loss of independence of the PSM regional branches. Independent local media offer a message that is rich, diverse, and tailored to the needs of their local audience: local political and social information, local activities and events, supporting projects that help and mobilise local communities. They are an important element in the landscape of Polish culture at the local level because they convey a significant part of information about the culture of local communities. Editorial offices of press titles and local/regional portals belonging to Polska Press remain under political influence, manifested in the style of informing, the selection of experts and the selection of topics. The message of local public media is also under political influence, manifested in its frequent one-sidedness, despite the rich programme offer.

[1] Krytykapolityczna.pl, K. Woźnikowski, Kto zdelegalizuje media samorządowe? PiS zabiera się za relikt z lat 90, 2023, https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kraj/pis-media-samorzadowe-wolne-media-andrysiak/

[2] K. Batko-Tołuć, Programme Director and a Board Member of the Citizens Network Watchdog Poland, 22 May 2023, email interview

[3] REM, Odpowiedź na skargę, 2022, https://www.rem.net.pl/data/20220720.pdf

[4] Press.pl, M. Niedbalski, KRRiT wciąż bez wpływu na wybór władz mediów publicznych. Ponad 6 lat od wyroku TK, 2023, https://www.press.pl/tresc/76188,po-ponad-szesciu-latach-od-wyroku-trybunalu-konstytucyjnego-krrit-wciaz-bez-wplywu-na-wybor-wladz-mediow-publicznych

Social inclusiveness – Medium risk (57%)

PSM channel TVP broadcasts programmes for national minorities (Ukrainian, Russian, Belarusian, Lithuanian, German, Kashubian) in six of its local branches.[1] In 2021, the number of hours increased to 177. Programmes for national and ethnic minorities and for the community using the regional language are currently broadcast in the programmes of twelve regional radio stations, a total of 1,695 hours since 2021.[2]

Due to the current political situation in the region, a minority that has become particularly present in the public media (and not only) in Poland is the Ukrainian minority. The offer of regional TVP branches includes programmes about the Ukrainians in their country and about Ukrainian refugees in Poland.

As for the situation of other minorities, their representatives themselves indicate that they do not feel sufficiently represented and some have the impression that “non-Polish” topics are not welcome on PSM. Their representatives have not been in the programming councils of public media for several years, even though they submitted their candidates at each recruitment.[3]

The public service media relatively rarely broadcast programmes covering some aspects of the lives of non-recognised minorities.

The main problems of the media for marginalised groups remain small funds and lack of financial support.[4] They function mainly thanks to the help of donors and small advertising revenues. Often at its base is the volunteering of journalists. This translates into irregular releases, low frequency, and delays. The public broadcaster presents an offer specific to some group (seniors, people with disabilities), but it is small, and there is no offer for the LGBT group at all. The internet is an essential tool in formulating the message about these communities, whether in the form of thematic portals, information portals (also at the local level) or internet radio.

Independent local media offer their recipients a wide range of news, largely satisfying their information needs, however, it should be noted that the number of these media is insufficient, and a significant part of the recipients do not have access to them. Furthermore, the widely available media of local governments and of the Polska Press group are deprived of independence, therefore it cannot be said that they satisfy CINs at the appropriate level.

[1] MSWiA, VIII RAPORT dotyczący sytuacji mniejszości narodowych i etnicznych oraz języka regionalnego

w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w latach 2019-2020, 2022, https://www.gov.pl/web/mswia/viii-raport-dotyczacy-sytuacji-mniejszosci-narodowych-i-etnicznych-w-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-w-latach-2019-2020

[2] KRRiT. Sprawozdanie Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z działalności w 2022 roku, 2023, https://www.senat.gov.pl/gfx/senat/userfiles/_public/k10/dokumenty/druki/1000/1002.pdf

[3]J. Hassa, director of the office of the Association of German Social and Cultural Associations in Poland, 15 May 20203, email interview.

[4] D. Mękarski, member of the Replika magazine team, June and October 20203, phone interview.

Best practices and open public sphere

The issue of the decline of local and community news seems to be clearly emerging in the social consciousness only now and is gradually beginning to arouse the interest of activists.

One major initiative undertaken in this dimension is the project to create an online map of independent media. The point is to stimulate social awareness, but also to draw the attention of the authorities and institutions in charge of the oversight of the problem.

A difficult financial situation is not conducive to searching for new solutions and forms of activity by the editorial offices themselves. Therefore, the initiatives of local media organisations are important, as they try to improve the quality and editorial independence of these media through training and helping local publishing houses in digital transformation, including using foreign grants, like the “Election Auditor of the Local Media Network” financed from the so-called Norwegian Funds[1], the “E-journalism university”, expanding knowledge of online journalism, or “Locals for Democracy”.[2]

Very valuable are academic initiatives aimed at analysing community media, which are still very poorly defined and recognised in Poland. An important example is the Monitoring Centre for Online Citizen Journalism operating at the Institute of Journalism and Social Communication of the University of Warmia and Mazury, which creates the Catalogue of Online Citizen Media in Warmia and Mazury. The project was co-financed from the state budget under the programme of the Minister of Education and Science called “Science for Society”.[3]

[1] Press.pl, Zaproszenie dla niezależnych mediów lokalnych, 2022, https://www.press.pl/tresc/73884,zaproszenie-dla-niezaleznych-mediow-lokalnych

[2] P. Piotrowicz, president of the management board of the Local Media Association, 10 May 2023, online interview.

[3] IDZiKS, 2023, https://cmidzo.uwm.edu.pl/