Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Bulgaria

Report authored by Orlin Spassov, Foundation Media Democracy / Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Nelly Ognyanova, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” and Nikoleta Daskalova, Foundation Media Democracy

Context

The term “news deserts” is not in use in public debate on the state of the media in Bulgaria. Nonetheless, problematic developments in the local media sector are frequently discussed, mostly in research carried out by journalistic organisations,[1] by NGOs,[2] in academic research,[3] and sometimes by media industry professionals. However, there is no structured discussion in the country aimed at promoting policy measures to enhance the condition of local and regional media.

Bulgarian legislation does not provide clear definitions for regional, local, and community media. Article 110 of the Radio and Television Act (RTA) stipulates that any radio and television broadcasting licence must state the range of distribution: national, regional, or local.[4] There are no legal provisions on the licensing or the functioning of community media, which do not exist in practice.

Since the transformation of the media landscape after 1989, the general state of local media in Bulgaria has been largely unsustainable. In the early 1990s, there was a rapid and unregulated development of the private sector and many local media outlets were established. Financial instability, however, has led to market changes (closures, mergers, short-lived projects, etc.), job insecurities and compromises in journalistic standards. In the context of economic and political weaknesses in the country, local and regional medias’ editorial independence has been seriously challenged, with susceptibility to external influences, initially reserved to the traditional media but subsequently expanding into the online sector.

The Severoiztochen (Northeastern) region is the area with the lowest number of local and regional media outlets in the country,[5] and among the regions with lower internet penetration. However, there is no distinct correlation between economically deprived areas[6] and news deserts.

[1] I. Valkov, “Media Under Fire. For More Editorial Responsibility. 2022 – Annual Survey of Freedom of Speech in Bulgaria”, Sofia: AEJ – Bulgaria, 2022. https://aej-bulgaria.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Media-under-fire_EN.pdf

[2] CSD, “Regional Media in Bulgaria: Limits of Survival”, Policy Brief No. 57, Center for the Study of Democracy, 2015, https://csd.bg/publications/publication/policy-brief-no-57-regional-media-in-bulgaria-the-limits-of-survival/

[3] Л. Симеонова, “Местната и регионална преса в България – между упадъка и надеждите на читателите”, Медиите на 21 век. Онлайн издание за изследвания, анализи, критика, 10 април 2023, https://www.newmedia21.eu/izsledvaniq/mestnata-i-regionalna-presa-v-balgariya-mezhdu-upadaka-i-nadezhdite-na-chitatelite/#_edn14

[4] Radio and Television Act (promulgated, State Gazette No.138, 24 November 1998), Council for Electronic Media, Council for Electronic Media, Bulgaria, Council for Electronic Media, https://www.cem.bg/files/1684834811_radio_and_television_act.pdf, 1998

[5] Aggregated data on local and regional TV and radio (licences for local or regional range of distribution and polythematic profile) and number of regional newspapers. Sources: CEM, “Public Register: Linear Services: Cable and Satellite Bulgarian”, Council for Electronic Media, Bulgaria, Council for Electronic Media, n.d., https://www.cem.bg/linear_reg.php?cat=1&lang=bg; CEM, “Public Register: Linear Services: Terrestrial Broadcasting”, Council for Electronic Media, Bulgaria, Council for Electronic Media, n.d., https://www.cem.bg/linear_reg.php?cat=2&lang=bg; NSI, “Issued newspapers by statistical regions, districts and type in 2022”, National Statistical Institute, Bulgaria, National Statistical Institute, 27 June 2023, https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/3598/issued-newspapers-statistical-regions-districts-and-type

[6] Eurostat, “Regional gross domestic product (PPS per inhabitant) by NUTS 2 regions”, Eurostat, European Union, Eurostat, last update 22 February 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TGS00005/default/table

Main findings

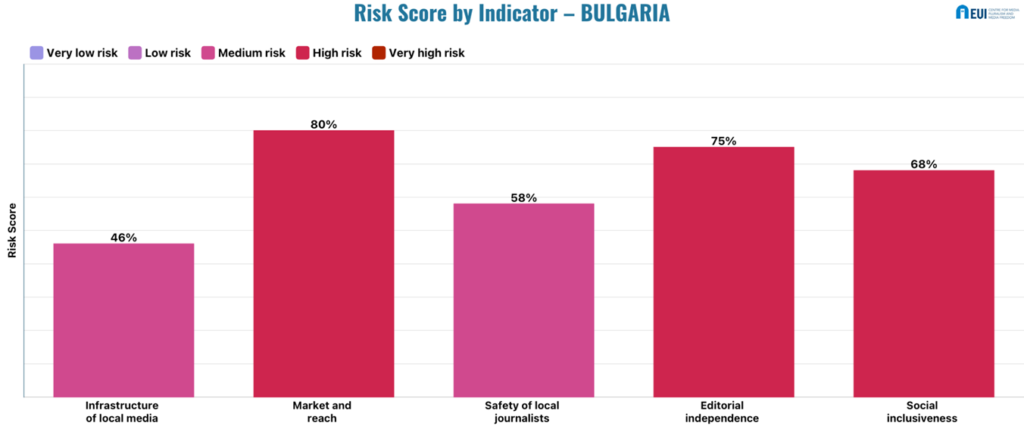

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (46%)

The evaluation of the infrastructure of local and regional media in Bulgaria points to a medium-risk situation. Most deprived of local news are communities in suburban areas (very high risk); media in these areas existed only exceptionally, over the past thirty years, and in the few known cases they were not sustainable.[1]

Rural areas are the second most problematic (high risk) in terms of access to local news. In the context of a lack of detailed data, Vesela Vatseva of the Bulgarian Association of Regional Media explains: “In Bulgaria, there are very few and rare print media in small towns. Rather, newsletters are printed on the occasion of significant events in the settlement. Also, the so-called radiotochka (local cable radio network) are used, through which the local municipality informs the population.”[2] Journalist Spas Spasov, founder of Za istinata online media platform for local and regional journalistic investigations, comments: “In the most common case, rural communities do not have local outlets, they are ‘covered’ by regional/local print media produced in the nearest town. As a result of distribution difficulties, newspapers in villages are often delivered directly by their publishers.”[3]

The local media landscape in urban areas in Bulgaria is very fragmented (medium risk). The presence and diversity of local media is uneven. Existing data indicate that newspapers are the most typical local media, available in all districts and regions. However, the total number of regional newspapers has decreased over the past 5 years: 127 in 2018, 113 in 2019, 111 in 2020, 106 in 2021, and 100 in 2022.[4] Most illustrative is the case of Varna, the third largest city in Bulgaria, where there is no longer a local daily following the closure of the Cherno More in April 2020.[5] In many cases online media outlets provide an alternative to the decline in print media offers. A lack of data, however, hinders the mapping of the online media landscape. At the same time, it is noteworthy that 11.8% of the individuals in the country have never used the internet, with the highest percentage recorded in the Severozapaden (Northwestern) region (16.7%).[6]

Aggregated data on the number of regional newspapers[7] and local and regional TV and radio programmes with a polythematic profile[8] show that the region with the smallest number of local and regional media is Severoiztochen, with 36, and the district with the smallest number of local and regional media outlets is Razgrad, Severen tsentralen (North central) region, with 4.

In the absence of accurate data, media professionals and experts have observed a downward trend in the number of local journalists.[9] According to Vatseva, “[n]ewsrooms with 15–20 people are now down to 5–10 people.” Against this background, the level of risk is lowest with regard to the public service media (BNT and BNR) and the main news agency (the state-owned BTA), which keep networks of local correspondents across the country.

The map you can find at the following link refers to the coverage of local and regional media in Bulgaria in 2023. The data for this visualisation was collected by the LM4D Bulgarian Country Team (Orlin Spassov, Nelly Ognyanova, Nikoleta Daskalova).

[1] Л. Гергова, “Еманципиране на квартала. Вестник за Люлин”, LiterNet, Bulgaria, LiterNet, 8(117), 2 August 2009, https://liternet.bg/publish25/l_gergova/emancipirane.htm ; Безплатен вестник Люлин (last update 9 April 2021) Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/bezplatenvestnik/

[2] Vesela Vatseva, Executive Director of the Bulgarian Association of Regional Media, 30/06/2023, online interview.

[3] Spas Spasov, journalist, Za istinata, 19/06/2023, online interview.

[4] NSI, “Issued newspapers by statistical regions, districts and type in 2022”, National Statistical Institute, Bulgaria, National Statistical Institute, 27 June 2023, https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/3598/issued-newspapers-statistical-regions-districts-and-type

[5] Л. Симеонова, “Местната и регионална преса в България – между упадъка и надеждите на читателите”, Медиите на 21 век. Онлайн издание за изследвания, анализи, критика, 10 април 2023, https://www.newmedia21.eu/izsledvaniq/mestnata-i-regionalna-presa-v-balgariya-mezhdu-upadaka-i-nadezhdite-na-chitatelite/#_edn14

[6] NSI, “Individuals who have never used the internet”, National Statistical Institute, Bulgaria, National Statistical Institute, 8 December 2023, https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/2828/individuals-who-have-never-used-internet

[7] NSI, “Issued newspapers by statistical regions, districts and type in 2022”, National Statistical Institute, Bulgaria, National Statistical Institute, 27 June 2023, https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/3598/issued-newspapers-statistical-regions-districts-and-type

[8] CEM, “Public Register: Linear Services: Cable and Satellite Bulgarian”, Council for Electronic Media, Bulgaria, Council for Electronic Media, n.d., https://www.cem.bg/linear_reg.php?cat=1&lang=bg; CEM, “Public Register: Linear Services: Terrestrial Broadcasting”, Council for Electronic Media, Bulgaria, Council for Electronic Media, n.d., https://www.cem.bg/linear_reg.php?cat=2&lang=bg

[9] I. Valkov, “Media Under Fire. For More Editorial Responsibility. 2022 – Annual Survey of Freedom of Speech in Bulgaria”, Sofia: AEJ – Bulgaria, 2022. https://aej-bulgaria.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Media-under-fire_EN.pdf ; E. Dimitrova in AEJ, “New Horizons in Journalism Conference 2022 (live)” video, YouTube, 1 December 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nDUVWbJRt8w

Market and reach – High risk (80%)

The highest risk for Bulgaria is identified in the market and reach indicator, with an overall risk score of 80%. Most problematic (very high risk) is the situation regarding revenue trends, the declining number of media outlets, and the lack of financial support provided by the government. Amidst the backdrop of a lack of precise data on local media revenues, media experts and professionals have repeatedly pointed to the deterioration of the local media market. The COVID-19 crisis in particular has had a very negative effect, leading to the reduction in volume and frequency of local newspaper publishing and even to the closure of some papers.[1] The Bulgarian research team confirmed the trend of decreasing resources in the local media sector, a shrinking local advertising market, and an unhealthy dependence of the media on local parties and administrations as a source of funds (mainly through advertising contracts and the provision of information services to local authorities).

Print media distribution has been curtailed in recent years. The number of points of sale for newspapers has decreased significantly since the bankruptcy of Lafka in 2020, until then a leading distribution chain of questionable reputation.[2] The distribution of paid TV (the most widespread form of TV consumption) is at the lowest level, but not necessarily declining, in the Severoiztochen region and in villages; in both cases, paid TV is used by 88.9% of households.[3] A subject of particular controversy has been the role of small cable TV and internet providers – which argue that they provide essential services to underserved communities[4] – amidst allegations they operate in the grey market, disrespecting tax and copyright obligations.[5] At the same time, their market positions have deteriorated due to the concentration and aggressive pricing offers of the big telecoms.[6]

The state does not provide specific support to local and regional media through subsidies, except for public service media. The provision of state advertising to the media is excluded from the regime introduced for public procurement. This allows the provision of state funds in return for favourable coverage, which has been one of the most serious problems in the local media sector in the past decade. In the presence of severe shortages of commercial advertising revenues,[7] financial difficulties, a shortage of human resources and outdated equipment, the majority of local media depend on the municipalities’ budgets for media services and on the budgets for publicising the EU projects implemented at the local and regional level. [8]

Disaggregated data on audience or market shares in local media sectors and geographical areas are not available. In practice, all districts are served by national media, which dominate the media market as a whole, with a high concentration in the TV and radio sectors.[9] The Reuters Digital News Report indicates that the weekly reach (offline) of regional or local newspapers in Bulgaria was 18% in 2019, 16% in 2020, 15% in 2021, 13% in 2022, and 8% in 2023.[10]

According to The European Media Industry Outlook, the proportion of consumers paying to access news content in Bulgaria in 2022 is 15.3%.[11] The Reuters Digital News Report also indicates that a small number of online users in Bulgaria pay for online news content: 7% in 2019, 10% in 2020, 15% in 2021, 12% in 2022, and 11% in 2023.[12] The overall low willingness of Bulgarians to pay for news content affects the consumption patterns of local news as well.

[1] В. Антонова, “Пандемията COVID-19 и размерите на медийната криза”, АЕЖ – България, 8 май 2020, https://aej-bulgaria.org/covid_media_crisis/ ; B. Dzhambazova, “Press Freedom Doesn’t Come Free”, in V. Berger et al (ed.), A Lockdown for Independent Media? Effects of the COVID–19 pandemic on the media landscape and press freedom in Central and Southeast Europe (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, June 2020), pp. 7–9, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/16392.pdf, ; 24 часа, “И Варна остана без вестник, местните медии умират, кои оцеляха”, 24 часа, 1 февруари 2021, https://www.24chasa.bg/bulgaria/article/9468362; И. Везенков, “Трагично”. Как COVID-19 доубива регионалната журналистика в България”, Свободна Европа, 9 април 2020, https://www.svobodnaevropa.bg/a/30543872.html

[2] Н. Стайков, “От щурм на пазара до фалит за три дни. Чия беше Lafka?”, Свободна Европа, 27 февруари 2020, https://www.svobodnaevropa.bg/a/30457585.html

[3] БАБТО, “Резултати от национално представително количествено проучване”, Браншова Асоциация на Българските Телекомуникационни Оператори, 2020, http://babto.bg/study

[4] OffNews, “Кабелни оператори: КРС работи за унищожаването на малкия бизнес и по-високи цени за клиентите”, OffNews, 20 януари 2020, https://offnews.bg/medii/kabelni-operatori-krs-raboti-za-unishtozhavaneto-na-malkia-biznes-i-p-719797.html

[5] Ю. Арнаудов, “Лъч светлина в сивия сектор на пазара за платена телевизия в България”, Tech Trends, 31 март 2021, https://www.techtrends.bg/2021/03/31/grey-sector-tv-bulgaria-10069/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Information validated by the interlocutors of the Bulgarian research team.

[8] Transparency International Bulgaria, “Местна система за почтеност: Индекс 2022”, Transparency International Bulgaria, 2022, http://lisi.transparency.bg/years/2022/#

[9] O. Spassov, N. Ognyanova and N. Daskalova. Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey in the Year 2022. Country Report: Bulgaria. Florence: European University Institute, 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75716/Bulgaria_results_mpm_2023_cmpf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[10] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “Digital News Report 2023: Bulgaria”, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 14 June 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/bulgaria; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “2022 Digital News Report: Bulgaria”, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 15 June 2022, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/bulgaria ; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “2021 Digital News Report: Bulgaria”, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 23 June 2021, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021/bulgaria ; N. Newman et al., Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2020), p. 65, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdfTop of Form

[11] PPMI, KEA and Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates, quoted in EC, The European Media Industry Outlook (Brussels: European Commission, May 2023), p. 90, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/european-media-industry-outlook

[12] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “Digital News Report 2023: Bulgaria”; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “2022 Digital News Report: Bulgaria”; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “2021 Digital News Report: Bulgaria”; N. Newman et al., Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, p.65.

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (58%)

The indicator on the safety of local journalists in Bulgaria points to medium risk (58%), with a high risk identified in the variables on working conditions of employed and freelance journalists. General labour and social security legislation in Bulgaria covers the media sector and regulates minimum rates of pay, open-ended and temporary contracts, termination of contractual relationships, including dismissal procedures, unemployment benefit systems and maternity or parental leave. Employees of the public BNR and BNT benefit from additional protection as a result of collective labour agreements between the employer and the respective trade unions. For years, however, the private local media sector has been facing poor working conditions, low wages (close to the minimum wage), a lack of trade union protection, delayed or unpaid wages for months and other violations of labour and social security legislation in practice.[1] Freelance journalists face serious challenges in their working environment, including self-financing of work trips and buying their own work equipment.[2]

The Mapping Media Freedom index[3] and the Council of Europe’s Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists[4] report on five cases of attacks and threats to the physical safety of local journalists in the period 2018–2022, showing a downward trend. Conversely, perpetrators of crimes against journalists are rarely prosecuted; impunity has been a widespread systemic problem, causing distress among journalists.[5]

In the past few years, journalists’ associations have issued statements of support, including for local journalists, in response to threats, attacks, assault, political, administrative or economic pressure. However, journalists’ organisations have limited impact on editorial independence at the local level.

SLAPPs are not yet defined in Bulgarian law. A study on SLAPP cases in Bulgaria has identified 57 cases in the period from 2000 to March 2023. The number of cases against local media and journalists is 15 (26% of all identified cases).[6]

[1] О. Спасов, Н. Даскалова & В. Георгиева, Да бъдеш журналист: състояние на професията (София: АЕЖ – България, Фондация Медийна демокрация, 2017), pp. 62–73, 111–112, http://fmd.bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/JournalistProfessionBG2017.pdf, ; Valkov, Media Under Fire. For More Editorial Responsibility. 2022 – Annual Survey of Freedom of Speech in Bulgaria; АЕЖ, “АЕЖ призова съда в Стара Загора да разгледа без ненужни отлагания казуса с неизплатени заплати на журналисти”, АЕЖ – България, 27 февруари 2023, https://aej-bulgaria.org/27022023/

[2] Valkov, Media Under Fire. For More Editorial Responsibility. 2022 – Annual Survey of Freedom of Speech in Bulgaria, p.46; Spas Spasov, online interview.

[3] ECPMF, Mapping Media Freedom: Bulgaria: 2018–2022, European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, https://www.mappingmediafreedom.org/#/

[4] Council of Europe, Safety of Journalists Platform: Bulgaria: 2018–2022, Council of Europe, https://fom.coe.int/en/pays/detail/11709492

[5] ФРГИ, “Тревожно е състоянието на журналистиката в България”, Фондация Работилница за граждански инициативи, 28 юли 2023, https://frgi.bg/bg/articles/aktualno/trevozhno-e-sastoyanieto-na-zhurnalistikata-v-balgariya

[6] Л. Георгиева – Матеева & С. Желева, Цента на свободното слово (София: Фондация Антикорупционен фонд), https://acf.bg/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/cenata_na-svobodnoto_slovo_web.pdf

Editorial independence – High risk (75%)

In Bulgaria, political parties and party leaders can legally own the media. In the past few years, politicians and family members have had ownership over local and regional media outlets (TV, online, print), often providing positive coverage of the corresponding political subject.

Although there are legal (Article 11 of the RTA) and self-regulatory (Chapter 3 of the Code of Ethics of the Bulgarian Media) provisions for editorial independence, pervasive political and commercial influences over local media editorial content often result in self-censorship among journalists.[1] Political actors, including local government institutions, are among the leading sources of external pressure in all local media sectors. In parallel, local media are reluctant to investigate issues that could affect local advertisers or the non-media business interests of their owners.

While in Bulgaria there are no state subsidies distributed to media outlets other than PSM, the distribution of state advertising, including funds for information campaigns under EU programmes, has long been a disturbing issue (very high risk). There are no publicly accessible criteria on the allocation of state advertising. As the 2023 Rule of Law report on Bulgaria outlines, “[t]he lack of a clear framework to ensure transparency in the allocation of state advertising remains a concern despite the creation of a working group which is meant to start working […] on this topic.”[2] There is only partial transparency on the part of the allocating authorities with regard to funds already distributed.[3] Public funding has provided local authorities with the opportunity to influence local and regional media, as this funding is a substantial part of media income.[4]

Under the Radio and Television Act, the Council for Electronic Media (CEM), the media authority, has three main sets of powers, including in the field of regional and local media: market structuring (licensing, registration, implementation of a notification regime for online platforms), monitoring of compliance with the law and licences, and powers in relation to public service broadcasting. In the past two years, there have been growing concerns regarding the independence of the CEM.[5]

The regional branches of the BNT and the BNR share the weaknesses commonly associated with regional media in general such as close ties with local authorities and a high level of self-censorship in reporting on local government issues.[6] Thus, more serious local political affairs are usually covered by journalists with the broadcasters’ national channels.

The lack of resources and challenges to editorial independence have had strong negative effects on content diversity in local and regional media. The Local Integrity System Index 2022 states: “With the exception of Sofia […] and some larger cities, the palette of media that cover the full spectrum of significant viewpoints, political and social stances is shrinking. Significant issues for society are absent from media politics.”[7] Copy-paste journalism and uncritical coverage of local authorities are common.[8]

[1] The problem has been repeatedly reported in research and monitoring evaluations in the last decade, as well as confirmed by the experts interviewed by the Bulgarian country team for the purpose of the Local Media for Democracy project.

[2] European Commission, “2023 Rule of Law Report. Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Bulgaria”, European Commission, 5 July 2023, p. 1, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-07/10_1_52568_coun_chap_bulgaria_en.pdf

[3] According to Article 6a (3) of the Tourism Act, the Minister of Tourism publishes monthly on the Ministry’s website a report with information on the funds spent, as well as on the effectiveness of advertising according to data provided by the platforms or search engines. Закон за туризма (обн. ДВ. бр.30 от 26 Март 2013), Lex.bg, https://lex.bg/bg/laws/ldoc/2135845281.

[4] See e.g., С. Спасов, “Предизборно и “на калпак” община Варна отново раздаде хиляди на медии”, Дневник, 19 март 2021, https://www.dnevnik.bg/bulgaria/2021/03/19/4186479_predizborno_i_na_kalpak_obshtina_varna_otnovo_razdade/, ; Transparency International Bulgaria, “Местна система за почтеност: Индекс 2022”.

[5] O. Spassov, N. Ognyanova & N. Daskalova. Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey in the Year 2022. Country Report: Bulgaria, p.13.

[6] Information provided for the purpose of the Local Media for Democracy project by journalists working in the public media.

[7] Transparency International Bulgaria, “Местна система за почтеност: Индекс 2022”.

[8] Information validated by interviews with journalists (Spas Spasov, online interview; interview with a journalist under the condition of guaranteeing their anonymity, 17 July 2023, in person), as well as by a survey among local civil society organisations (15–30 June 2023) and sample media monitoring, conducted by the Bulgarian research team for the purpose of the Local Media for Democracy project.

Social inclusiveness – High risk (68%)

The indicator on social inclusiveness scores high risk for Bulgaria, 68%. Medium risk is identified only in terms of PSM coverage. The BNT and the BNR provide minority-related content,[1] albeit with some significant deficiencies. The BNT broadcasts a daily 9-minute news bulletin in Turkish, catering to the Turkish minority, the country’s largest minority group. Additionally, since June 2023, the BNT has been offering Ukrainian-language news bulletins, primarily aimed at Ukrainian refugees. The BNR and the BNT are predominantly neutral in reporting on minority groups.[2] Coverage of migrants, on PSM as well as on private media outlets, is mainly in the context of illegal trafficking of migrants from the Middle East and North Africa, with the authorities being the main spokespersons on the issue.[3]

The leading private media outlets do not provide regular content dedicated to minority and marginalised groups. News reporting is predominantly on migrants, followed by Roma and LGBTQ people, with very scarce coverage of the Turkish minority.[4] Most affected by negative coverage, including hate speech and disinformation, are Roma and LGBTQ people.[5] There are outlets that address marginalised groups in particular (people with disabilities, women, youth etc), but they have limited impact and reach.

Local and regional media content does not adequately meet the critical information needs of local communities. The most serious problem in this respect stems from the close ties of the local press with the local government, as a result of which critical coverage of political life is severely limited.[6] Political and economic dependencies of local outlets prevent them from sufficiently protecting the public interest and undermine readers’ trust in them.[7]

[1] Republic of Bulgaria, “Fifth Report submitted by Bulgaria Pursuant to Article 25, paragraph 2 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities – received on 22 October 2021”, Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/5th-sr-bulgaria-en/1680a4495f, .

[2] И. Инджов, ЛГБТИ – Новата медийна мишена вместо ромите? (Образът на малцинствените и уязвимите групи в българските медии) (София: БХК, 2023), https://www.bghelsinki.org/web/files/reports/173/files/2023-indjov–the-image-of-minority-groups-in-the-media.pdf

[3] Ibid.; also monitoring by the Bulgarian country team.

[4] According to a study on media representation of minorities and vulnerable groups in the online content of 13 leading media outlets in January–February 2023, see Инджов, ЛГБТИ – Новата медийна мишена вместо ромите? (Образът на малцинствените и уязвимите групи в българските медии), p.8.

[5] Ibid.; see also: C.E.G.A Foundation, Care for Truth – Against Fake News and Anti-Roma Disinformation (Sofia: C.E.G.A Foundation, 2022), https://cega.bg/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EN_CARE-4-TRUTH_book_web.pdf

[6] Information validated by interviews with journalists (Spas Spasov, online interview; interview with a journalist under the condition of guaranteeing their anonymity, 17 July 2023, in person) and a survey among local civil society organisations (15–30 June 2023), conducted by the Bulgarian research team. See also Transparency International Bulgaria, “Местна система за почтеност: Индекс 2022”.

[7] Симеонова, “Местната и регионална преса в България – между упадъка и надеждите на читателите”.

Best practices and open public sphere

Legacy media outlets make efforts to expand their reach by migrating online, offering online access to their print archive, encouraging local communities to report news, and publishing audience-generated content (photos, videos, and opinions). Some local and regional media disseminate their editorial content on their social media channels. Against the background of widespread problems with editorial independence and critical coverage, the Za istinata online media platform has a network of journalists across the country and publishes investigations on local matters.

In addition, there are popular social media groups where local communities report and discuss information relevant to the community. In some areas, including rural areas and neighbourhoods, some of these groups are particularly effective in communicating and discussing local issues. In other areas, participants are more passive. Usually, the content of such groups is very eclectic in regard to media content, user-generated content, anecdotes, advertisements and the promotion of private services. However, misinformation also takes place. Overall, the picture in the country is mixed, and such initiatives are only partially and not consistently effective in tackling the problems associated with the provision of local news.

Map of Local and Regional Media Coverage in Bulgaria

This map shows the coverage of local and regional media in Bulgaria in 2023. You have the option to filter by format, district (NUTS3 region), and NUTS2 region. Hover over a district (NUTS3 region) to view the number of media outlets, including a detailed breakdown by format. Below the map is a bar chart which counts the total number of media by NUTS2 region. Clicking on one of the bars in the chart below the map also allows you to filter by region. The data for this visualisation was collected by the LM4D Bulgarian Country Team (Orlin Spassov, Nelly Ognyanova, Nikoleta Daskalova).