Gábor Polyák, Professor of Media Law and Media Policy, Eötvös Loránd, University / Senior Research Fellow, Mertek Media Monitor and Ágnes Urbán, Associate Professor, Corvinus University Budapest / Director, Mertek Media Monitor

Context

Local government in Hungary is made up of local municipal governments, county municipalities, the metropolitan municipality and district municipalities: a total of 3,178 municipalities, each with its own mayor and representative body. The local governments operate with narrow powers, further reduced since the COVID-19 pandemic, and are economically at the mercy of the central government. Local media are essentially a budgetary issue for municipalities, with the annual budget decree setting the operational framework for municipal media.[1]

There are no debates about local news deserts. However, the state of local media became the focus of professional debate after 2016, when all the county newspapers were taken over by Fidesz oligarchs and in 2018 became part of Fidesz’s media conglomerate, KESMA.[2] The problem of “news desert” in the Hungarian media system appears in the context of the one-party dominance of Fidesz over the entire media landscape, in which freedom and diversity of information are severely limited. In the case of local media, the one party-dominance means that readers have very limited access to independent information on issues of local relevance.

Local media and community media are defined in the Media Act[3], as only radio and television. There is no definition in Hungarian law applicable to the print press, online and social media. The definition of local media is based on the audience coverage, i.e. it is solely based on the geographical area covered and the size of the audience reached. The differentiation based on audience does not affect the content broadcast only the media service fee payable by the media service provider to the media authority.

Based on the Media Act, community media services are media services serving a specific social, national, cultural, or religious community or group, or serving the specific needs of the population of a particular locality, region or catchment area, to give information and access to cultural programmes, or broadcasting programmes serving the objectives of the public service media as defined in the Media Law for the majority of its broadcasting time. The community media provider does not have to pay a service fee. After 2010, when the current government first won the national election, pro-government community radio networks were created (Lánchíd Rádió, after 2015 Karc FM, since 2023 Hír FM), and churches were given radio broadcasting opportunities in this form (Catholic Radio, Maria Radio, Europe Radio). There is hardly any real community radio serving the needs of local or cultural groups.

After the regime change of 1989-1990 the state privatised county newspapers very quickly and the first foreign investors appeared in the Hungarian media market. By the early 2010s, all the county newspapers were owned by foreign investors (Axel-Springer, Ost Holding, Russmedia, Radio Bridge Media Holdings Ltd). From 2014 onwards, these publishers and newspapers were bought up by pro-government entrepreneurs, and since 2018 all county newspapers have been owned by the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA).

Another traditional group of local newspapers is the local municipality-owned and financed newspaper. In many cases, these are newspapers serving local political propaganda purposes, regardless of the political colour of the municipality concerned. Although their operation is financed exclusively or predominantly from public funds, there are no guarantees, either in law or in local regulations, that impartial local information can be provided. This does not mean, of course, that all municipal newspapers serve party-political purposes.

The municipality also owns other media. The 1996 Media Law, which regulated the media framework for the first time after the regime change, still explicitly prohibited the creation of local media holding companies. Nevertheless, local television stations run by municipalities were already in operation in the 1990s. In the Hungarian market, local television does not operate commercially, which is explained by the small size of the market.

The newest players in the local news media are the small local online news sites, many created after 2016 with the help of journalists dismissed from county papers. The oldest independent local news site that has been funded through advertising and grants is Nyugat.hu. Journalists who were let go from local newspapers launched the news site Szabad Pécs in 2017 and Debreciner.hu in 2019. The importance of independent local news sites has been recognised by donor organisations, as most of the local media’s funding comes from grants and donations from readers. In 2023, eight local news sites (Borsod24, Debreciner, KecsUP, Nyugat.hu, Enyugat, Szabad Pécs, Szegeder, Veszprémkukac) started closely cooperating, including content exchange (on the website szabadhirek.hu which has currently 13 members), joint tenders and other activities.[4]

Local radio, on the other hand, started out as a very vibrant market. The first radio networks were music radio stations (Juventus Radio, Radio 1), which became real competitors of national commercial radio stations. In the second half of the 2000s, Klubrádió started operating as a networked political talk radio station. However, its network was completely shut down in 2011 under the new media law and the new media authority, and in 2020, it lost its Budapest frequency, and can only operate as an online radio.

In 2010, community radio lost its original function, and the Media Council authorised networks of political and religious radio stations under this designation.

After 2010, the new media authority, the Media Council, completely redrew the radio map. The previously well-established music networks lost their frequencies, and a growing network of religious and political radio stations took over the frequencies of the former local radio stations. The new music radio network Rádió 1 and the political talk radio network Karc FM were established in this period. In contrast, the expansion of two new music networks, Best FM and Gong FM, has been visible in recent years. These radio stations are government-controlled; Karc FM (since 2023 Hír FM) and Gong FM are directly owned by KESMA. In the Hungarian local media, the phenomenon of news deserts is, therefore, not fundamentally the result of the lack of coverage of local news services in certain municipalities or regions but rather of the fact that much of the local media is under strong political influence. This is true not only for the pro-government media but also for most of the local newspapers in opposition-led municipalities. Only in those municipalities with an independent news portal or where the local government has created the conditions for the independence of the media it owns can residents find a non-partisan source of information.

[1] Law, 2011. évi CLXXXIX. törvény Magyarország helyi önkormányzatairól, 2011, https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a1100189.tv.

[2] Mertek Media Monitor, Media Landscape after a Long Storm. The Hungarian Media Politics since 2010, Mertek.eu, 2021, https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MertekFuzetek25.pdf.

[3] Law, 2010. évi CLXXXV. törvény a médiaszolgáltatásokról és a tömegkommunikációról, 2010, https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a1000185.tv.

[4] Media1.hu, Összefogtak a vidéki független lapok, 2023, https://media1.hu/2023/07/06/osszefogtak-a-videki-fuggetlen-lapok

Main findings

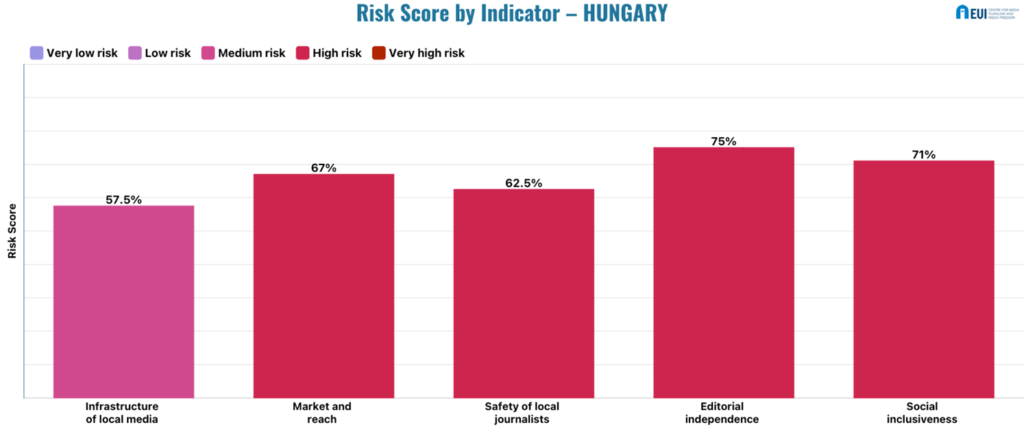

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (57,5%)

In the Hungarian media market, county newspapers are available everywhere. Most municipalities and all the districts of the capital have their local newspapers. There is no public database for municipal newspapers/websites. Still, as the number of municipalities is stable and municipalities are trying to maintain their existing media, it can be assumed that their number is relatively stable.

According to the media authority, 385 cable and 37 terrestrial local TV stations are operating in the country[1], a low number compared to the 3,100 municipalities. Local TV is available everywhere except in the smallest municipalities. The media authority’s register lists 94 local radio stations and 44 district stations. Of the local radio stations, 60 are linked to a Fidesz-affiliated or a church-owned network, i.e. only 34 are independent local radio stations.

On the local media market as a whole, there are very few independent services and press products that are not the product of a complex media company, i.e., non-municipal, non-networked services. Except for a few independent local radio stations and local online newspapers, most local media are in a situation of dependency. While this may be positive regarding the range of content, as it provides a more sustainable economic basis for local media, it is highly problematic regarding diverse and impartial local coverage.

The end of newspaper sales at post offices, the government’s drain on local government resources, and significant regional disparities in internet penetration and digital literacy also significantly limit rural residents’ access to local news. Outside Budapest, the county newspapers and music radio networks close to the government have the best chance of reaching audiences.

Outside Budapest, it is typically challenging to find journalists.[2] The local editors of county newspapers tend to be older journalists, and it is difficult to find replacements.

Municipal newspapers have a small editorial staff of 3-6 people, and even fewer journalists work for independent online newspapers. In case of some municipal television stations, the municipality outsources all content production to an external company. Smaller local television stations produce very few programmes with small crews. Networked local radio stations largely maintain a technical staff, while independent local radio stations have their news editors.

In 2011, the PSM—now the Duna Media Service Provider Company providing television, radio, and online services, as well as running the only Hungarian news agency[3]—restructured by the Fidesz government, unexpectedly closed most of its regional studios.[4] The PSM has since sourced local coverage to local television stations. It has no correspondent network of its own.

[1] NMHH, Register of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority, 2023,https://nmhh.hu/szakmai-erdekeltek/nyilvantartasok?HNDTYPE=SEARCH&name=doc&page=1&fac_provider_theme=mediafelugyelet&fld_keyword=”médiaszolgáltatások nyilvántartása”&_clearfacets=1&_clearfilters=1.

[2] Oživení, z.s, Transparency International, Sieć obywatelska, Mertek Media Monitor, The Crisis of Local Journalism in V4 Countries and the Specific Role of Municipal Newspapers, 2023, https://www.oziveni.cz/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Booklet_2_interaktivni_strany_V4.pdf; Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely, Az értelmes beszéd kis szigetei – Helyi nyilvánosságok és helyi média Magyarországon, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L96wqIfomMA; Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely, Büszkék lehetünk arra, hogy még létezik a helyi média, 2022, https://mertek.atlatszo.hu/buszkek-lehetunk-arra-hogy-meg-letezik-a-helyi-media/.

[3]G. Polyák and Á. Urbán, Funding of the Hungarian Public Service Media – 2015, in Iris Plus, Online activities of public service media: remit and financing, https://rm.coe.int/iris-special-online-activities-of-public-service-media-remit-and-finan/1680945613.

[4] Nyugat.hu, Leépítik az MTV regionális stúdióit, 2011, https://www.nyugat.hu/cikk/mtv_regionalis_musorok_megszunes; Delmagyar, Szegedi körzeti stúdió: ˝utolsó bástya voltunk˝,2015, https://www.delmagyar.hu/szeged-es-kornyeke/2015/03/szegedi-korzeti-studio-utolso-bastya-voltunk.

Market and reach – High risk (67%)

There is only sporadic data about the overall revenues of local media. No separate database is available for local media companies, the data can be checked by individual searches. Based on random company checks, revenue trends are rather mixed; some are decreasing, and some are increasing.[1]

The distribution of local newspapers is outsourced, at least in the larger settlements, and local newspapers are usually distributed together with commercial leaflets. In smaller municipalities, the municipality typically handles distribution itself.

The government supports local media in several ways.[2] The Media Council Funding Programme (Médiatanács Támogatási Programme) sponsors local and regional television and radio stations in a tender scheme to cover their overhead costs, technical improvements or the costs of their radio or television programmes.[3] There were no dramatic changes in the subsidy between 2018 and 2021. 2019: +6,1% (compared to 2018) 2020: -1,1% (compared to 2019) 2021: +12,3 (compared to 2020).[4] The Media Council is not an independent organisation; all five members of the Media Council were delegated by the ruling party Fidesz.[5] Municipalities fund or subsidise local media, and there is very mixed practice on how much political loyalty is expected. Some mayors expect loyalty from local media, and others respect the independence of local media outlets. The distribution of government advertising at the national and local levels is completely opaque. The real problem is not the amount of financial support but the lack of transparency.[6]

For community radio, the role of state advertising is as important as for commercial media –especially in the case of Karc Fm/Hír FM, which is owned by the pro-government KESMA conglomerate. In the case of church radio, state support is indirect through the funding of churches.

Independent local news portals are active in international competitions. Many foreign donor organisations support the work of these small, non-profit organisations. This project-based support is risky, and the implementation of projects can be to the detriment of the outlets’ core activity. In addition, the media receiving these grants have been exposed for years to smear campaigns and were stigmatised by government communication as “dollar media” representing foreign interests.

No advertising data is available for the local market. Based on the national advertising data (2018-2022), only digital revenues increased in real terms (+57,2%). The decline in the print newspaper market was very strong (-33,8%), but there was also a decrease in the radio (-14,8%) and television (-5,5%) sectors in real terms.[7] Paywall and crowdfunding are prevalent in national media, but local media brands are not strong enough to follow this model. A few independent local online sites have tried this in recent years, but background interviews show they have not generated significant revenue from these sources.

The local media market is too fragmented to calculate market share and concentration ratio (very high risk). At the same time, the county’s daily newspapers are all owned by a single owner, the Fidesz-affiliated KESMA. The local radio market is dominated by pro-Fidesz radio networks. Local newspapers and local television stations are owned and maintained by the municipalities. Thus, overall, local media markets are fairly concentrated, with real competition only in those markets where independent local news portals operate.

Mérték Media Monitor and the Median Public Opinion and Market Research Institute have conducted several surveys on the Hungarian public news consumption and information patterns. In 2020 and 2023, these also included questions about how respondents inform themselves about local affairs. This shows that in 2023, 11% of respondents would be informed at least weekly by local radio, with a further 5% less frequently (same figure in 2020: 10% at least daily, 10% at least weekly and 8% at least monthly). In the case of local (municipal) newspapers, 9% were informed at least monthly and 2% less frequently (same in 2020: 33% and 10% respectively).[8]

The local media markets in Hungary are economically quite high-risk, as they are characterised by: the concentrated ownership of county newspapers and local radio stations; the governmental party affiliation of these dominant or monopoly owners; the discriminatory distribution of state advertising; the weak economic strength and advertising potential of the vast majority of local markets; the unpredictability of municipal funding; and the scarcity of domestic funding coupled with the constant political attacks on foreign funding.

[1] State, Database for annual financial reports of the companies, 2023, https://e-beszamolo.im.gov.hu/oldal/beszamolo_kereses.

[2] Oživení, z.s, Transparency International, Sieć obywatelska, Mertek Media Monitor, The Crisis of Local Journalism in V4 Countries and the Specific Role of Municipal Newspapers, 2023, https://www.oziveni.cz/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Booklet_2_interaktivni_strany_V4.pdf;

[3] Media Council, Media Council Funding Programme, 2023, https://tamogatas.mtva.hu/.

[4] National Media and Communication Authority, Parliamentary Reports of the Media Council, 2022, https://nmhh.hu/mediatanacs-orszaggyulesi-beszamolok.

[5] K. Bleyer-Simon, G. Polyák and Á. Urbán, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Hungary, 2023, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75725.

[6] K. Bleyer-Simon, G. Polyák and Á. Urbán, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Hungary, 2023, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75725.

[7] Advertising Association (MRSZ) and its co-associations, Press release of the Hungarian Advertising Association (MRSZ) and its co-association, 2023, https://mrsz.hu/cmsfiles/f0/52/MRSZ_sajtokozlemeny_2022_media-komm-tortak_FINAL_230320_EN.pdf.

[8] E. Hann, K. Megyeri, Á. Urbán, K. Horváth, P. Szávai and G. Polyák, News Islands in a Polarized Media System, 2023, Mérték Media Monitor, https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Mertek-fuzetek_30.pdf.

E. Hann, K. Megyeri, G. Polyák and Á. Urbán, An Infected Media System ,2020, https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Infected_media_system.pdf.

Safety of local journalists – High risk (62.5%)

The situation for journalists working in local media is not uniform. KESMA’s county newspapers guaranteed existential security until the 2022 elections, but serious cutbacks were made afterwards. No quantitative data on journalists’ salaries and other working conditions was found. According to market reports, pro-government county newspapers and radio network employees work in good working conditions for competitive salaries. Local self-government owned media offer more modest opportunities, and working conditions vary with the ever-changing funding of local governments. Independent local news portals typically have editorial teams of 2-5 people. Working conditions are significantly influenced by the availability and extent of current tendering opportunities and foreign funding. Neither project-based grants nor crowdfunding allow for long-term planning and development.[1] Overall, almost all local media segments are characterised by serious political and economic instability, and journalists’ working conditions are unstable.

The media outlets affiliated with KESMA are just as heavily biased servants of government policy at the local level as they are at the national level. Analyses of county newspapers have also confirmed the bias of local news published in these newspapers.[2]

The county papers also publish national news. In this case, the content is centrally edited, and literally, the same news iteam appears in the county papers as in the national Magyar Nemzet newspaper or the free Metropol. These news items exclusively convey the governing party narrative. Even among municipality-owned media outlets, impartial reporting tends to be the exception, regardless of whether the municipality is controlled by the governing parties or the opposition parties. Especially in politically charged situations, the municipality’s leadership uses these media outlets for political purposes, typically to promote the mayor.[3] Despite these media outlets being publicly funded, no legislation or other document guarantees impartial, balanced editorial activity. As previously analysed, the exceptions to this rule are some local newspapers (mainly Budapest district papers) where the mayor is not affiliated with any political party.[4] Independent local online newspapers are the most impartial forums for local information, respecting professional and ethical standards of journalism. These media outlets have been created precisely to provide an alternative to partisan local reporting, and they are fulfilling this commitment.

Physical attacks and threats against Hungarian journalists are rare. There is one such documented case involving local journalists: the staff of Nyugat.hu were threatened in a Messenger message that “on their way home, they will be hit from behind with a blunt object and then the knife will appear”. The case was investigated by the prosecutor’s office.[5] Political attacks and smear campaigns have been reported by several journalists.[6]

Only a few SLAPP cases are known on the local level. Requests for rectification do occur, but the number is not very high. As in national politics, the local political leadership prefers to ignore published information and opinions and is not interested in debating dubious issues. At the same time, there is no anti-SLAPP legal framework in the country, and thus meritless lawsuits can tie up considerable resources for news media.

The most significant risk for journalism is that journalists working in the ruling party media are under constant political pressure; in the municipality-owned media, there is also political pressure, coupled with economic uncertainty; and independent local news portals lack any predictable, stable funding. Journalists in the independent media face severe difficulties in obtaining information from the government and even from municipalities.

[1] Oživení, z.s, Transparency International, Sieć obywatelska, Mertek Media Monitor, The Crisis of Local Journalism in V4 Countries and the Specific Role of Municipal Newspapers, 2023, https://www.oziveni.cz/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Booklet_2_interaktivni_strany_V4.pdf;

[2] Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely, Megyejáró: megyei napilapok elemzése – összegzés, 2019, https://mertek.eu/2019/02/04/megyejaro-megyei-napilapok-elemzese-osszegzes/.

[3] K-Monitor Blog, Így használták kampányra köztisztségüket politikusaink, , K-Monitor, 2022, https://k.blog.hu/2022/04/02/_kormanyzati_hirlevel_es_polgarmesteri_tajekoztatas_koztisztsegek_es_kampany?layout=5; 24.hu, N. Gergely Miklós, Megszületett a NER-t idéző balos propaganda, de van más is – milyen tömegsajtót csinál az ellenzék közpénzből?, 2021: https://24.hu/belfold/2021/05/28/kerulet-lap-ellenzek-kozpenz-baloldal/.

[4] D. Dercsényi, Felmérte lapunkat a Mérték, 2022, https://jozsefvarosujsag.hu/felmerte-lapunkat-a-mertek/.

[5] Nyugat.hu, Ügyészségi határozat született a Nyugat.hu-t ért fenyegetés ügyében – a Facebook is segített megtalálni az elkövetőt, 2022, https://www.nyugat.hu/cikk/amp/ugyeszegi_hatarozat_szuletett_a_nyugat.hu_t_ert_a?fbclid=IwAR2Xp0iTryq5c6oreEziJo8hYHFvn_oRklsclvhVsdgIiAX2nAyTkfvSYdk.

[6] I. Lozovsky (OCCRP), They Tried to Frame Us’: New Assault on Hungarian Journalists Highlights Media Freedom Crisis in the Heart of Europe, 2023, https://www.occrp.org/en/37-ccblog/ccblog/17408-they-tried-to-frame-us-new-assault-on-hungarian-journalists-highlights-media-freedom-crisis-in-the-heart-of-europe

Editorial independence – High risk (75%)

The Media Law contains some conflict-of-interest rules for all media services, including for local media services. However, while formal conflict of interest rules are not violated, there is no genuine guarantee of avoiding political interference.

No rules apply to the impartial coverage in local print and online newspapers or the use of public funds.[1] As part of KESMA, the county newspapers openly and unilaterally convey the government narrative, supported by a significant amount of public advertising. This means that they have a secure funding base compared to other local media players, such as independent local media outlets, which instead are largely dependent on donations and grants. In the case of the KESMA county papers, political and economic influence are intertwined, and potential commercial advertisers—which are typically few in the Hungarian local market—often place ads in these papers for political reasons. According to the same Media Law, local media service providers must also provide balanced information in their programmes about local, national, and European events and controversial issues of public interest. However, the Media Council’s parliamentary reports submitted over the last five years do not mention local media cases.

Overall, the Media Council acts in relation to infringements committed by local media. The Media Council and the National Media and Infocommunications Authority have some regional offices, but they mainly deal with telecommunications issues or supervise a specific area. They have no links with the local media in their respective cities. Problems have been detected over the years regarding the overall independence of the regulator’s action.

The Hungarian PSM has no local branches, as they were closed by the Fidesz government between 2011 and 2015[2]. Since then, local media under contract with the PSM have been delivering local news. As the political independence of the PSM as a whole has been severely compromised,[3] the editing of local news is not impartial.

While this is the basis for continuous political interference in editorial decisions, thanks mainly to independent local online newspapers in a few large cities, and the few remaining independent local and community radio stations, diversity has not disappeared completely from the local media.

[1] I. Codreanu, L. Ganea, I. Godársky, E. Hanáková, M. Klíma and K. Rasťo, Media market trends and distortions in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, 2021, https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Mertek-fuzetek_20.pdf.

[2] Delmagyar, Szegedi körzeti stúdió: ˝utolsó bástya voltunk˝, 2015, https://www.delmagyar.hu/szeged-es-kornyeke/2015/03/szegedi-korzeti-studio-utolso-bastya-voltunk.

[3] K. Bleyer-Simon, G. Polyák and Á. Urbán, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Hungary, 2023, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75725.

Social inclusiveness – High risk (71%)

Based on the news programme analysis of the Media Authority, minority actors accounted for 2.5% of the news programmes (this corresponds to long-term proportions).[1] The proportion of Roma is the lowest in public service media (5.9%), which is much higher in commercial channels. The proportion of other national minorities in Hungary is also low (3.3%). The public service media mainly focuses on Hungarian minorities living in neighbouring countries and immigrants – the coverage of the latter being predominantly negative. The refugee crisis was portrayed in the public service television channel M1 as a security threat, the humanitarian crisis aspect was neglected. Public media programmes use the term “migrant”, not “refugee”. Migrants are portrayed in a highly negative light in public service news programmes.[2]

The presence of minority languages in private broadcasting is not typical. There is a television with a Roma theme (Dikh TV), mainly with a musical focus. This is also in Hungarian, but there is also a Lovari language programme. Radio Dikh is a Roma radio, but news service is not included. Tilos Radio (independent community radio available on local frequency in Budapest and online) has a public affairs and cultural magazine for Roma every second week (Cékla).

Some local media outlets give a high priority to local community issues, while other media outlets do not. The municipality newspaper of Budapest 8th district was analysed in 2022.[3] It found that public issues (politics, local affairs, social issues) covered 55% of the content. A recent analysis[4] of two local newspapers in Debrecen about a planned battery factory showed the differences between municipal media and independent media. The local government news site published more articles emphasising the issue’s economic, technological, or environmental aspects, and several articles were published about similar battery plants in Germany. The independent Debreciner covered local civic groups’ opinions and reported the factory’s possible consequences for the whole town. A comparative content analysis of three municipality newspapers in the campaign period before the April 2022 parliamentary election showed different editorial practices. One newspaper (in Debrecen) was seriously biased in the municipality; only the viewpoints of politicians from the ruling party could appear. The other two newspapers provided the possibility for all candidates to introduce their positions. To conclude, local media only exceptionally become the main forum for public debate, even on local issues. It is only the very few independent news portals that can address local issues effectively.

[1] NMHH, National Media and Communication Authority, 2023, https://nmhh.hu/cikk/236654/Tarsadalmi_sokszinuseg_a_hirmusorokban_2022_januar_1__december_31.

[2] É. Bognár, P. Kerényi, E. Sik, R. Surányi and Z. Szabolcsi, Migration narratives in media and social media. The case of Hungary (BRIDGES Working Papers #07), 2023: https://www.bridges-migration.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/WORKING-PAPERS-BRIDGES_07_FINAL_OK_with-doi_v2.pdf;

V. Messing and G. Bernáth, Infiltration of political meaning- production: security threat or humanitarian crisis? The coverage of the refugee ‘crisis’ in the Austrian and Hungarian media in early autumn 2015, 2016, https://cmds.ceu.edu/article/2016-12-13/report-coverage-refugee-crisis-hungarian-and-austrian-media-published-cmds.

[3] Mertek Media Monitor, Quantitative content analysis of Jozsefvaros municipality newspaper, 2022, https://jozsefvaros.hu/otthon/hirdetotabla/hirek/2022/09/elkeszult-a-jozsefvaros-ujsag-ujabb-mediaelemzese/.

[4] J. Bódi, K. Horváth, I. Kovács, and Á. Urbán, Distinctive local media markets – one story, multiple perspectives, 2023, https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Mertek-fuzetek_32-2.pdf.

Best practices and open public sphere

There are independent local online sites that are trying to play a watchdog role in challenging political and economic circumstances. Cooperation has already started between them. Nyugat.hu is the biggest independent local site, it has already launched its podcast. Debreciner, another independent local site, has regular events for the readers to enhance audience engagement.

There is an exceptional initiative, the Nyomtassteis movement, whose founder has also been interviewed for this project and discussed in a blog post.[1] It aims to distribute content rather than produce it. The idea was inspired by the fact that in rural areas, especially in villages, and small towns, many elderly people live without internet access: they are mainly reached by government propaganda, as most printed newspapers, radio and television are linked to the governing party. Every week, Nyomtassteis puts together a short news summary of the most essential news and tries to get it into as many people’s mailboxes as possible. The system is based on volunteering: anyone can print an A4 news sheet and put it in their local mailboxes. Nyomtassteis does not focus on local news but is distributed in rural areas. Independent local media outlets are active in social media and try to be as innovative as possible. Podcasts are already relatively widespread (e.g. Nyugat, Debreciner, Szabad Pecs, Veszprem Kukac), and some media also have YouTube channels (Nyugat, Kecsup). Mecseki Muzli has a rather unique concept. It is not a news portal but provides a high-quality weekly newsletter about the city of Pecs.

[1] U. Reviglio and D. Borges, Newsletters, podcasts and slow media: successful news media strategies to engage audiences in the attention economy (Blogpost published at the website of the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom), 2023, https://cmpf.eui.eu/newsletters-podcasts-and-slow-media/.