Download the report in .pdf

English

Author: Jelena Dzakula

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In the United Kingdom (UK), the CMPF partnered with Dr Jelena Dzakula, who conducted the data collection and commented on the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

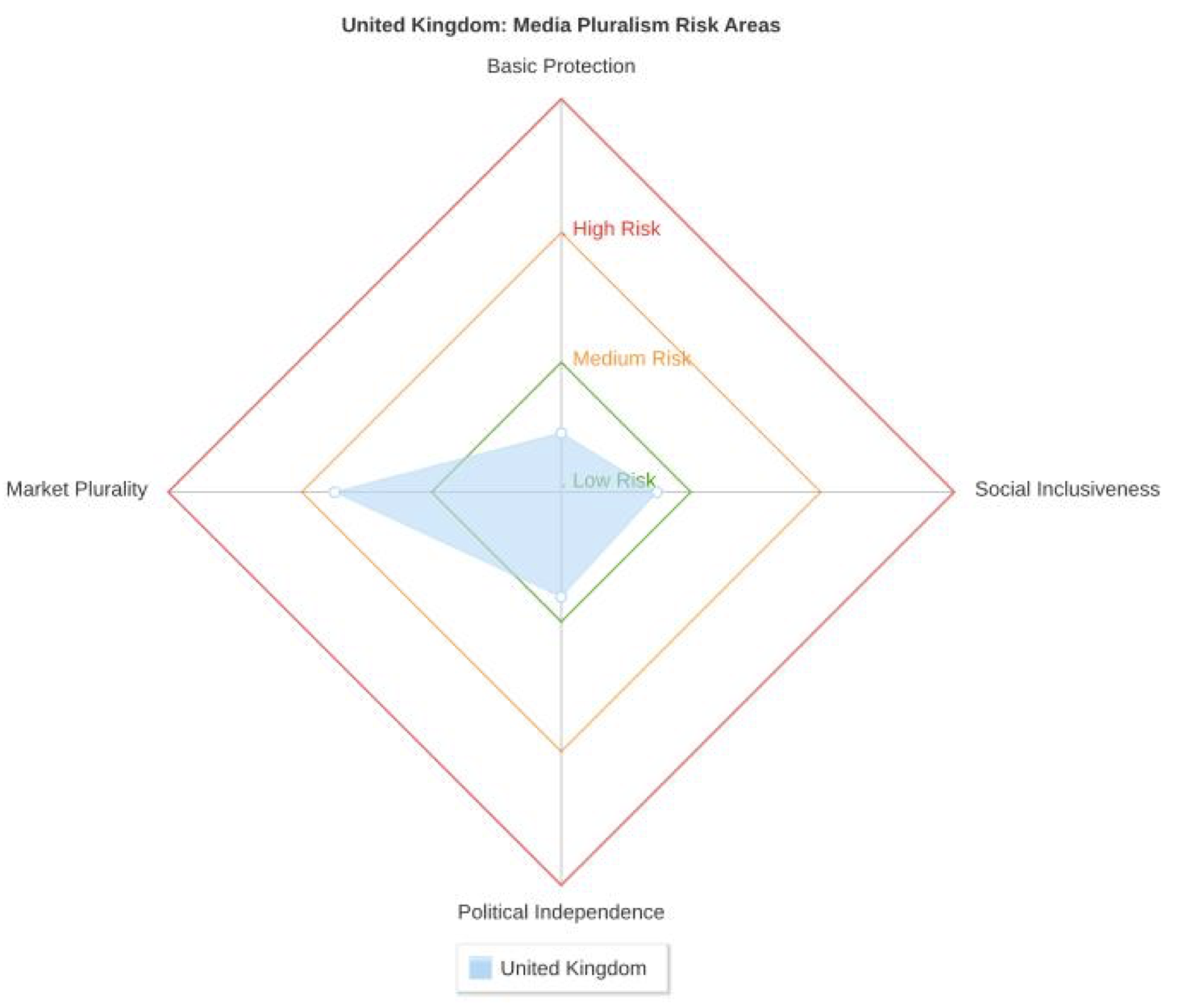

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

With the 2016 estimate of the population being 65,110,000 and the 242,495 km2 area it covers, the United Kingdom is the fourth most densely populated country in the European Union [2]. Its official language is English, 92.3% of its population reported English as their main language and 7.2% reported other languages as their main language with Polish topping this list [3]. Four Celtic languages that are spoken in the UK, Welsh, Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish, are all recognised as regional or minority languages, subject to specific measures of protection and promotion. 12.8% of the UK population identify themselves as belonging to an ethnic minority with the largest groups being Indian, Pakistani, Black, and Mixed. Ethnic diversity varies significantly across the UK, with London and Leicester being the most multicultural [4].

The UK is a developed country and it is the second-largest economy in the EU. It is also one of the most globalised economies with the dominant service sector (78% of the GDP). The creative industries are important in the UK and the key areas include London and the North West of England, which are also the two largest creative industry clusters in Europe [5].

When it comes to the political system, the UK is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of governance, and it consists of four countries—England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the last three of which have devolved administrations. The monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II, is the Head of State. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, currently Theresa May from the Conservative Party, is the head of government. By far the biggest political event in 2016 has been the referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU that resulted in a majority vote tor leave the EU; the so-called Brexit. This will have far reaching consequences for media policy in the UK, and it is expected that the Article 50 will be triggered in March 2017.

When it comes to the media landscape, total UK communications revenues generated by telecoms, TV, radio and postal services have increased over the recent years to £56.5bn in 2015. These figures exclude the newspaper industry, which has seen falling revenues for years [6].

There are more than 600 TV channels available in the UK as well as 21 local TV stations with further services planned to go on air. UK has a strong PSM tradition, with 5 channels having obligations in this area. Since 2012, all TV broadcasts are in a digital format, following the end of analogue transmissions, and they delivered via terrestrial, satellite and cable as well as over IP. Digital terrestrial is by far the most popular method, with pay-digital satellite remaining the same since 2011, and only incremental growth in digital cable take-up in recent years. Free-to-view satellite services such as Freesat have grown slowly, and account for the smallest proportion of all homes. The radio sector is developed as well with 337 analogue radio stations, 41 UK-wide radio stations, and 239 community radio stations.

When it comes to the newspaper industry in the UK, one of its main characteristics is that there is a large national newspaper sector that is read by about 70% of the adult population. This press is commonly divided into three sectors – ‘quality’, ‘middle market’ and ‘red-top tabloid’. For more than 20 years, all the papers in the latter two categories have been tabloid in size. More recently, three of the ‘quality’ titles abandoned the broadsheet format and adopted either a ‘compact’ (The Independent and The Times) or Berliner (The Guardian) size. This change stimulated much debate over whether the national press was abandoning ‘serious’ journalism [7]. There is high concentration of ownership when it comes to national, regional and local level, and, perhaps most importantly, the newspaper industry’s business model is facing serious challenges.

Although the UK ad market in general grew steadily over the years, national newspapers lost more than £150m in print ads in 2015, a 11% fall to 1.2bn, and digital revenues slowed significantly [8]. Across titles in the quality national newspaper market, print advertising fell by 9.6%. But it was worse among popular and tabloid titles, which endured a 16.2% decline in print advertising. With circulation figures declining as well, the press industry has not found a sustainable revenue model.

Speaking of the online world, in total, 87% of UK adults say they use the Internet, on any device, either at home or elsewhere. Search engines are by far the most popular source when looking for information online (92%). 4G mobile services are now available to 97.8% of UK premises, 81% use broadband both fixed and mobile, and superfast fixed broadband take-up is 42%. Proportion of UK adults with a smartphone is 71%, and there has been a growing reliance on and preference for mobile phones.

When it comes to consumer habits, for most age groups, watching TV accounts for 39% of the total time spent on media and communications, with only 16-24s spending more of their time communicating, 32% vs. 29% for watching. Live TV and radio combined dominate and account for nearly two-fifths of adults’ media and communications time, and a fifth of all media and communications time is spent media multi-tasking. Overall, the main PSM channels’ weekly reach appears resilient and they have retained a majority share of viewing – 57% both when it comes to linear TV and on-demand. The biggest changes in watching habits are among 16-24s since their time spent watching live television has declined to 36% of total viewing time, while free, paid on-demand and short- form video now represent around half of this age group’s viewing. In addition, watching broadcast television among 16-24s has had the steepest decline (27%) since 2010 followed by children (26%) [9].

Television is by far the most-used platform for news, with 67% of UK adults saying they use TV as a source of news, 41% use the Internet or apps for news, and newspapers are used by 31%.

The most important issues for media policy in the previous year or so have been attempts to reform press self-regulation, although the status quo remains. Also, there has been a worrying trend in surveillance laws, with the latest development being the adoption of the so-called Snooper’s Charter, which is discussed in details later in the report.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The implementation of the MPM in the UK revealed that the majority of the risks to media pluralism are low. Freedom of expression is safeguarded both in law and practice, as well as right to information. The Media authority, Ofcom, is seen as efficient and powerful, and the reach and variety of the media is at the appropriate level. The media are relatively independent of political influence, and the UK is seen as a leader when it comes to media literacy.

There is plenty of research conducted and published by academics, research institutions, regulators, consultancies and research agencies. This makes the implementation of the MPM viable and there have been no major issues in terms of availability of data. There are some areas where research methods are not advanced enough, for example when it comes to the online figures in terms of revenues and viewing figures.

However, very significant risks exist when it comes to market plurality. Ownership concentration in all measured horizontal and cross-media markets is high both in terms of market share and audience concentration. This is seen as a result of the consistent liberalization of the rules by both the Governments on the left and on the right since the Broadcasting Act 1996 due to ideological considerations.

Consequently, there are issues when it comes to editorial autonomy particularly when it comes to the press. Broadcast services are subject to Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code, thus their editorial autonomy and fair representation is safeguarded. However, self-regulatory system for the press has been seen as inefficient and there are problems with commercial pressures on editorial autonomy, most notably revealed by the Leveson inquiry[10]. This has been a long-standing issue in the UK and it has not been resolved up to this date.

However, concentration of ownership also has another unwanted consequence and that is the political power it gives to proprietors. Here the best example is the influence Rupert Murdoch exercises in the UK.

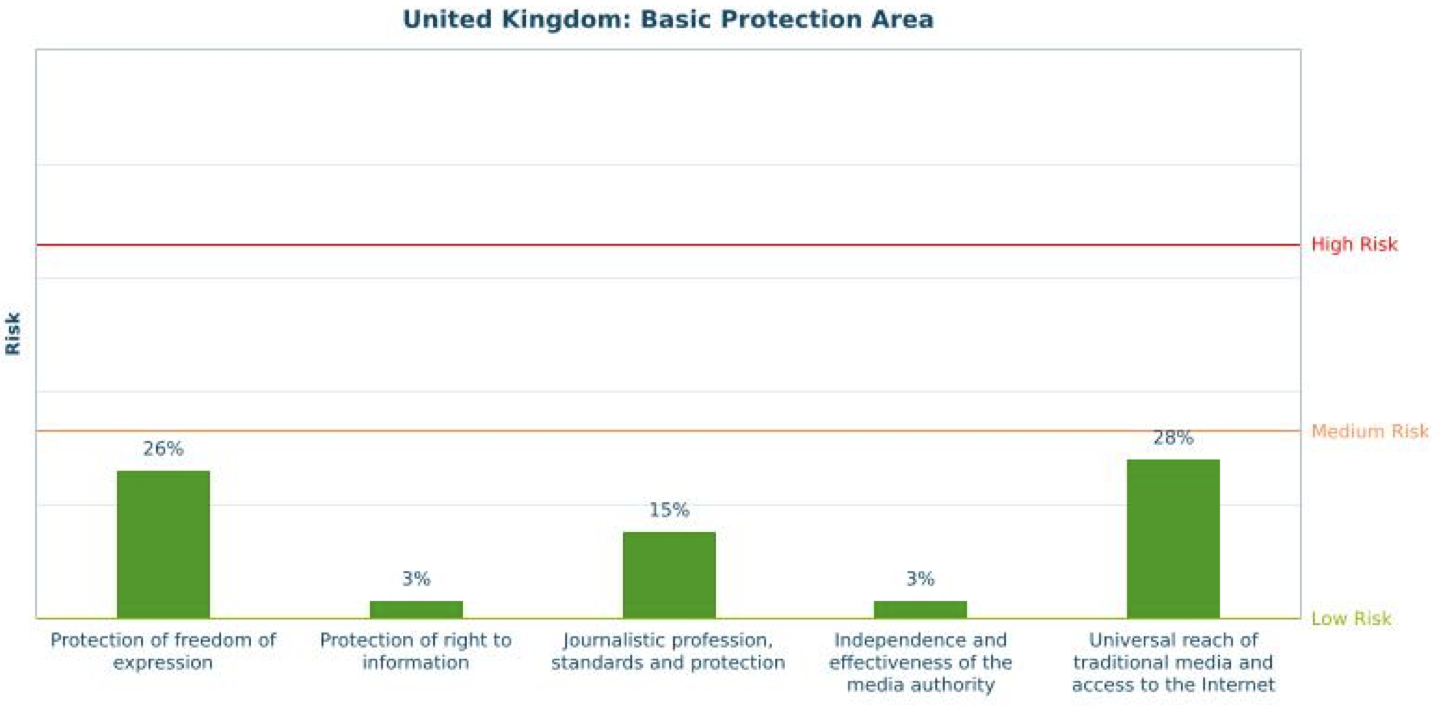

3.1. Basic Protection (15% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

When it comes to the Basic Protection area none of the indicators have revealed a significant risk for the UK and the overall risk remains low. Freedom of expression has been explicitly recognised in the UK’s legal framework, the UK has ratified relevant international conventions without significant exemptions and there are legal remedies available for citizens in cases of perceived or actual violations. Moreover, there have been no violations in this area in practice and online freedom is generally not considered an issue in the UK with the ISPs not acting arbitrarily when it comes to blocking. Right to information is recognized in two pieces of legislation, which are considered to be robust, respected in practice, show respect for privacy, and there are legal remedies.

A series of anti-terrorism and surveillance legislation have caused concern as they could have an impact on freedom of expression: Terrorism Act 2006, Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA), and the most recent Investigatory Powers Bill 2016 (the so-called Snooper’s Charter). These Acts have been criticized for their broad and vague definitions, new prohibitions, giving too much and indiscriminate power to the Home Secretary and the Government when it comes to communications data, and they could negatively affect investigative journalism. There have been no significant issues in practice so far, which makes this area low risk.

When it comes to the journalistic profession, on the positive side, the access to profession is open in practice with no legal or self-regulatory instruments in this area, there have been rare threats to journalists, and the digital safety of journalists is not seen as an issue. The protection of journalistic sources is guaranteed in law and it is also respected in practice. The working conditions are solid, with some irregularities in payments and some job insecurity, which does not affect the overall low risk. There are also journalists’ associations, which are seen as effective when it comes to safeguarding professional standards. For example, the biggest association, The National Union of Journalists, has around 38,000 members and extensive resources and training. In addition, although defamation has not been decriminalised, the UK has reformed and improved its defamation legislation with the Defamation Act 2013.

However, very significant issues exist when it comes to the commercial pressures on editorial independence. Although major owners claim they do not interfere with editorial decisions, editors are appointed by them and the recent Leveson inquiry has revealed systematic influence on the editorial content. This is a long-standing problem in the UK and it has not been resolved since the Leveson recommendations have not been implemented in their entirety. Currently, the Government is consulting again and it remains to be seen if the self-regulatory system will be changed.

When it comes to the audiovisual media authority, which in this case is Ofcom, there are no major risks to media plurality stemming from the way it operates. There are many provisions ensuring it is able to perform its duties properly, and Ofcom has been perceived as an independent, efficient, transparent, and powerful regulator with the Government not arbitrarily overruling its decisions.

When it comes to the universal reach of the media, the only medium risk comes from Internet speeds, which are 15 Mbps. Otherwise, there are no risks with the 99% of the population covered by the signal of all public TV channels, 95% covered by the signal of all public radio stations, 99% is covered by broadband including the rural population, and 88% have a broadband subscription.

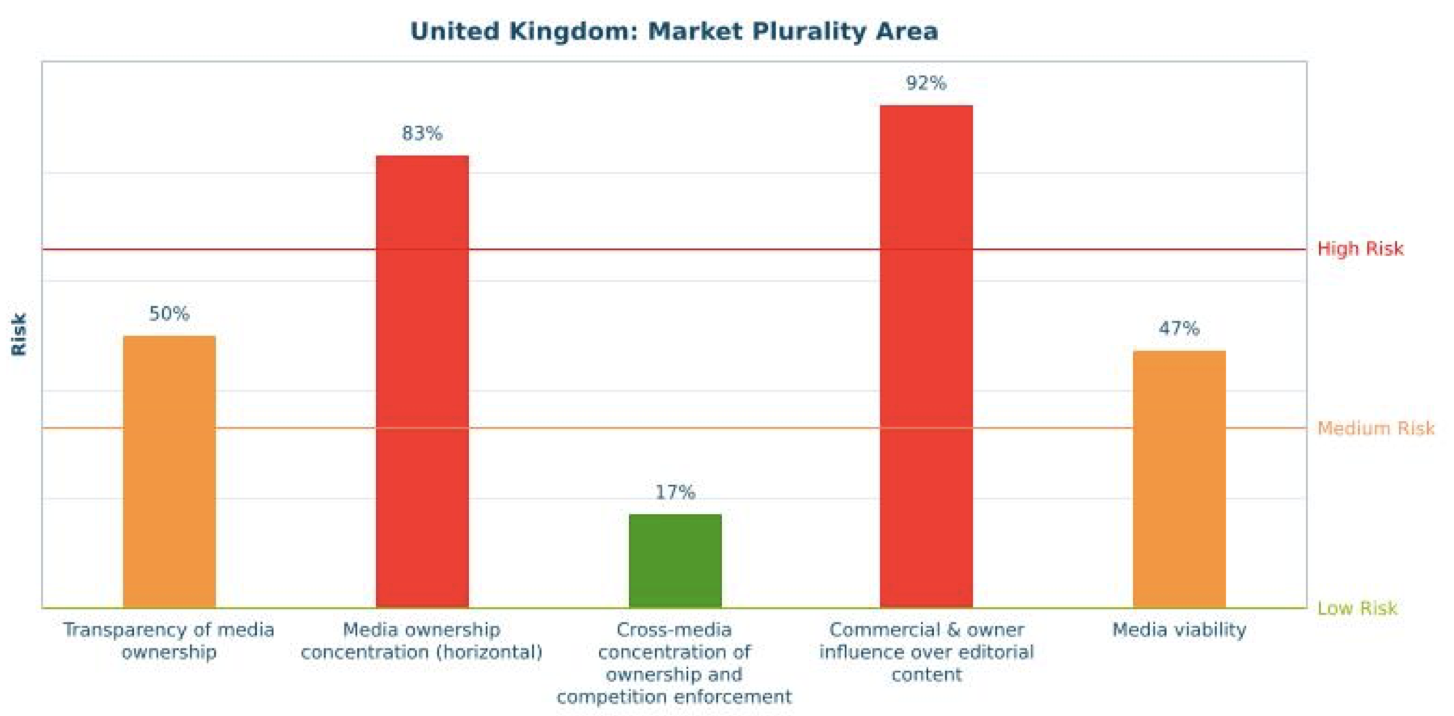

3.2. Market Plurality (58% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Market plurality indicators have revealed significant issues in the UK, and this is one of the most problematic and concerning areas with only one set of indicators presenting low risk.

Starting with the obligations regarding transparency of media ownership, there are legislative provisions in this area with the Companies Act 2006. Although this Act contains provisions regarding transparency and disclosure of information about companies including their statement of capital and shareholdings, as well as the duty to publish annual reports every year, a few aspects are seen as posing a medium risk (50%). To begin with, there are no specific requirements to publish changes in ownership structure outside annual reports, and there are no specific requirements that media companies need to report their ownership structure to the media authority. In addition, the law makes reference to shareholders, which are sometimes big investment funds, and it takes research and knowledge to establish who owns which media company despite these transparency requirements.

When it comes to legislative provisions for both horizontal and cross-media ownership, the situation presents a risk to media plurality. It is only when it comes to the television sector that there are laws and regulations preventing concentration of ownership, but the requirements are seen as weak and liberalised. The rules regarding cross-media ownership concentration are extremely weak and only prevent one entity owning both a Channel 3 licence (which has some PSM requirements) and one or more national newspapers with an aggregate market share of 20% or more. High concentration of ownership can also be prevented by merger control and the rules are prescribed in the Enterprise Act 2002 with the so-called public interest test, which can be employed when the company being taken over has a turnover in excess of £70 million or when one of the parties has a 25% or above market share in the relevant broadcasting or newspaper sector.

There are number of bodies relevant in the area of media ownership and mergers in the UK: Ofcom, Competition and Market Authority (CMA), and the Competition Appeal Tribunal. These bodies have sufficient powers and have been seen as efficient, but the system is complex. The market in the UK is highly concentrated but the issue might not be the efficiency of the bodies involved but rather the ideology that has underpinned the relaxation of the rules over the years since the Broadcasting Act 1996.

Consequently, there is high concentration of ownership in all of the markets when it comes to both market and audience shares:

- Top4 audiovisual media owners command 92% of revenues and 74% of audiences;

- Top4 radio owners command 88% of both revenues and audiences;

- Top4 newspaper owners command 75% revenues and 71% of readership;

- Top4 owners across different media markets command 68% of revenues; and

- Top4 Internet providers command 59% of revenues and 90% subscribers.

Not surprisingly, there are very serious issues with commercial and owner influence over editorial content, as it has been discussed above.

Moving to another issue, Media viability presents medium risk (47%). Although the revenues for the audiovisual media sector have increased slightly in the past few years as well as expenditure for online advertising, they have remained the same for the radio sector and they have decreased when it comes to the newspapers. On the positive side, media organisations have been developing new sources of revenues, such as pay walls, going digital only, creating content for commercial entities and brands, there are also community-driven hyperlocal journalism websites, and there have also been attempts to use crowd-funding. The number of people using the Internet and mobile devices to access the Internet has also been increasing.

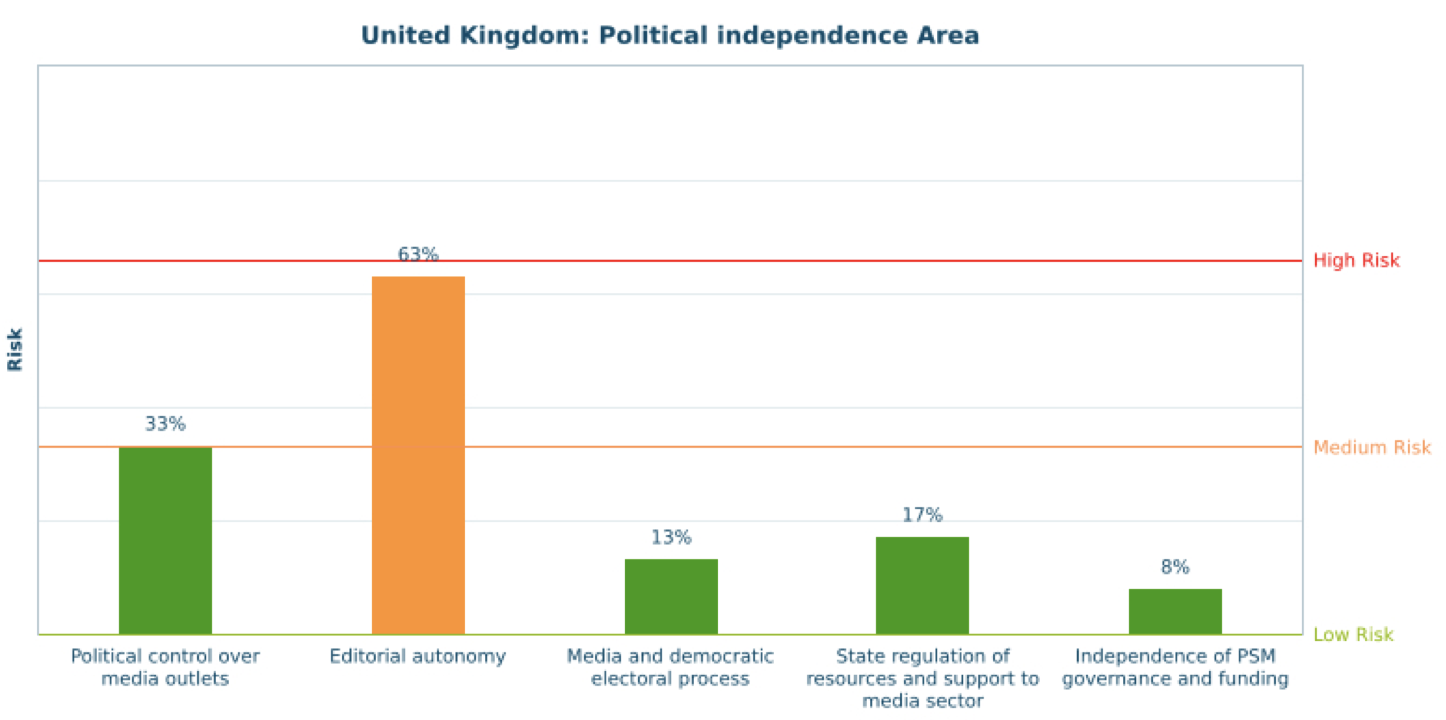

3.3. Political Independence (27% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The risks to pluralism coming from political independence in the UK are on the overall low.

Political control over media outlets is not a problem in the UK with legislative provisions prohibiting political ownership of audiovisual media and radio. These provisions are effectively implemented and, in practice, there is no political control. Although there is no legislation preventing political control of newspapers, news agencies, and distribution networks, this does not happen in practice. However, the influence of media owners with specific political orientations is an issue, especially when it comes to Rupert Murdoch, one of the most important media moguls in the UK who, with his family, owns major newspapers in the UK such as the Times and the Sun, and has recently submitted a bit to take full ownership of BskyB, one of the major broadcasters in the UK. This risk is most evident when it comes to the national press level, but is low overall when regional papers are considered. A factor that contributes towards assessing the risk as low when it comes to this issue is that political preferences of newspaper owners can and has been switched (as is the case with Rupert Murdoch who changed his support from the Labour to the Tory Party).

There are issues when it comes to protecting editorial autonomy from political influences. Therefore, this indicator scores a medium risk (63%). This is partly due to the fact that regulatory safeguards to guarantee editorial independence differ between markets. Thus, Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code, which applies to TV and radio, sets provisions to ensure that news, in whatever form, is reported with due accuracy and presented with due impartiality. The Code applies to all the broadcasters apart from the BBC, which has its own provisions regarding this set in the Royal Charter. In 2017, as Ofcom takes over regulation of the BBC, its Broadcasting Code will apply to its services as well. However, there are no self-regulatory measures that stipulate editorial independence in the news media and that guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief. In addition, there are no regulatory safeguards that apply to online media.

When it comes to determining if editorial content in the news media is independent from political influences in practice, this is a complex and nuanced issue. Although there is no political ownership of news media, as discussed in other questions, media owners have political preferences and there is a cosy relationship between them and the politicians. The most recent case that is worrying is the so-called Whittingdale scandal where the press have not published the story of the Culture Secretary dating a sex worker. This also shows the extent to which the politicians are influenced by the press.

Moving forward to the issue of the Media and democratic electoral process, there is a low risk here since there is legislation aiming at fair representation of political viewpoints in news and informative programmes on PSM channels and services, which is implemented effectively, and political representation is fair and balanced in practice. There is also legislation that imposes rules aiming at guaranteeing access to airtime on PSM and private channels and services for political actors during election campaigns. Political advertising on television channels is banned, which covers PSM.

When it comes to state support and resources, the risk is low. The legislation on spectrum allocation is fair and transparent, as well as legislation on the distribution of direct subsidies to media outlets, where we can only talk about community radio. These rules are effectively implemented by Ofcom and there are no known issues in this area. The only indirect subsidy is the VAT exemption for newspapers, and although there are no laws regarding the distribution of state advertising to media outlets, it is distributed in a fair manner with transparent criteria, beneficiaries, and amounts.

Independence of PSM governance and funding is another area where the risk is low. There are legal provisions, Royal Charter for the BBC and Communications Act 2003 for other PSBs, which provide fair and transparent appointment procedures for management and board functions in PSM as well as when it comes to Director General. These provisions guarantee independence from government and other political influence, they are implemented effectively, and there are no issues in practice.

In addition, media law prescribes transparent and fair procedures in order to ensure that the funding of PSM is adequate, and PSM are consulted on these issues. Here we can only talk about the funding of the BBC, and the procedures are set in the Royal Charter.

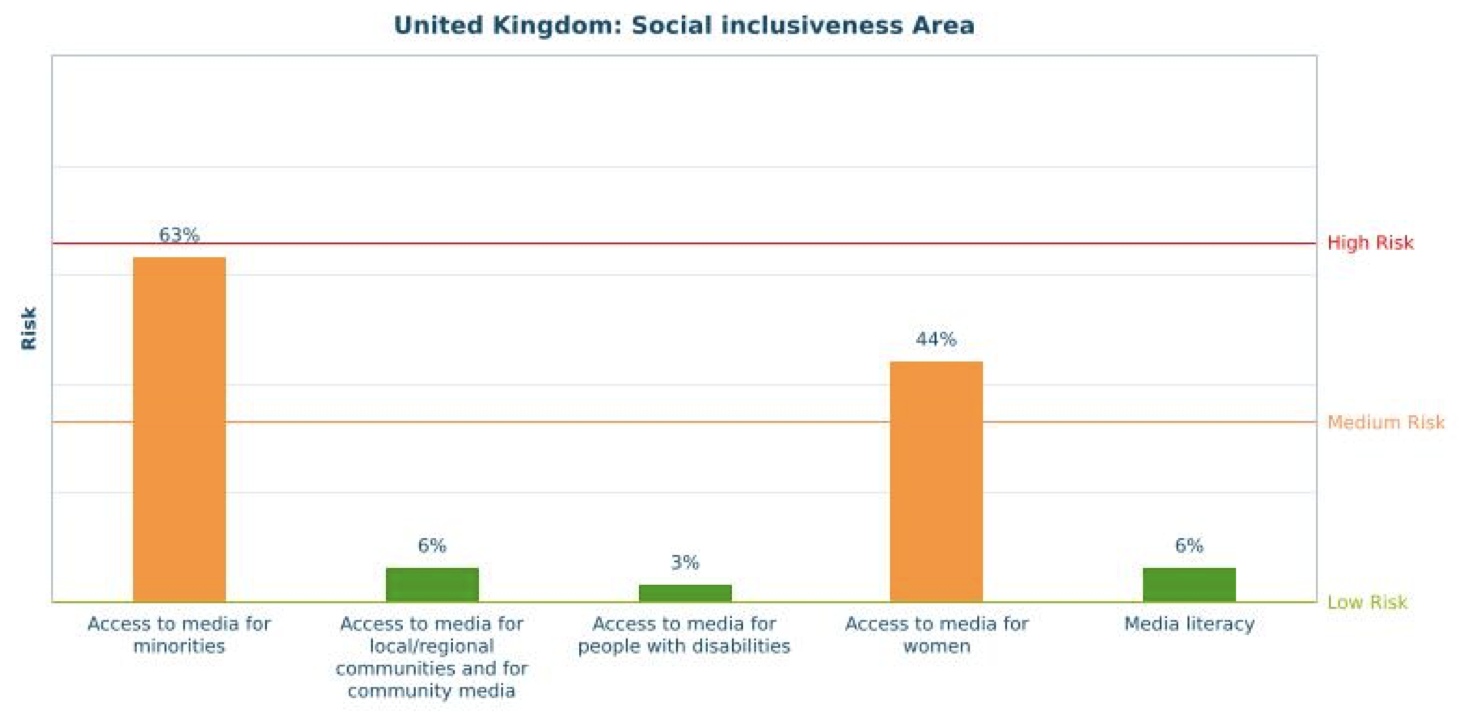

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (24% – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

When it comes to Social Inclusiveness, two indicators present medium risk while three indicators are at low risk. The indicators covering access to media for minorities and for women present medium risk and there are a few reasons for this. Speaking of the former, there are no laws to guarantee access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities. Moreover, there is widespread consensus in the UK that there are issues with under-representation of minority groups in the media, although there is no evidence that the minorities are denied access to airtime on PSM channels. The situation on the radio is slightly better since there are many local and regional radio stations that serve minorities, as well as community radio stations, most of which are dedicated to minorities. The situation has been improving with many broadcasters introducing measures to increase access for minorities and Ofcom has recently introduced a monitoring scheme.

The set of indicators related to Access to media for women have also revealed a medium risk. There are positive developments. First, there is an Equality Act (2010) that ensures that women have equal rights when it comes to employment in media organisations, and it is it implemented effectively. Second, the PSM have a comprehensive gender equality policy covering both personnel issues and programming content, and Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code contains a number of rules which are relevant for non-discrimination in programming. However, only 34% of PSM management board members are women, and there is high risk when it comes to representation of women in the news, and among news reporters.

When it comes to local/regional and community media, there are legislative provisions to ensure regional or local media access to media platforms. These are ‘must carry’ rules, which relate to PSM and main commercial networks (Channel 3 and 5), which all have regional programming. UK also has local TV and community radio, which is of local nature, and there are legislative provisions to ensure spectrum frequencies are reserved for both. Government does support local/regional media through other tools and policy provisions. PSM are obliged under their licences to have regional programming, local TV legislation was passed in 2011, and there is a small government fund for community radio. In addition, BBC is required to broadcast news in regional languages. Moreover, there is also the Gaelic Media Service and a Welsh TV channel (S4C). The only significant community media is present on the radio, which although with limited funds, operates well.

When it comes to Access to media for people with disabilities, there is a well-developed policy in this area. In addition, Ofcom conducts periodic reviews of the way broadcasters are meeting the regulatory requirements. According to the latest Ofcom report in 2015, the broadcasters are voluntarily delivering significantly over the statutory requirements. When targets are missed, it is only marginally. In addition, the legislative requirements for audio description apply also to on-demand audiovisual media.

The media literacy policy is also well-developed with a strong tradition in this area. The existing measures are coherent and up-to-date with the latest societal changes, and the UK has been seen as a leader in this area when it comes to regulation, industry commitment, research and educational programmes. However, media education in the UK is currently vulnerable as policy makers favour an instrumental approach that moves away from critical (and arguably political) dimensions of media literacy, and media literacy is present in the education curriculum only to a limited extent. There are also concerns that the legislative base for media literacy is not strong enough with few formal references to media literacy. However, there are strong initiatives when it comes to non-formal education with a range of programmes widespread across the country and across different groups of people. What also contributes to low risk in this area is that a vast majority of the population has basic or advanced digital usage and communication skills (83% and 91% respectively).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the implementation of the MPM 2016 in the UK has yielded some positive results and revealed that, in many areas, the risks to media pluralism are low. Further on the positive side, there is a lively debate regarding media policy in the UK, and public interest groups, although weakened and less well resourced, are still significant players. They have made positive strides that led to many indicators being assessed as low, such as access to the media for people with disabilities.

On the other hand, there are significant risks that need to be dealt with urgently, which might be overlooked and overshadowed by Brexit. In this process, there is the need to maintain positive provisions that aim to protect media plurality once the UK leaves the EU. One of the examples is the newly adopted General Data Protection Regulation that comes into force in 2018. This is particularly important bearing in mind the series of intrusive surveillance and anti-terrorist legislation in the UK, the most recent being the Snooper’s Charter. It is important to safeguard citizens’ and consumers’ privacy and right to data protection, and both government and the regulators should aim to protect fundamental human rights.

One of the most significant risks to media plurality in the UK comes from high concentration of ownership. Steps need to be taken by both government and Ofcom to prevent further consolidation, and new ways to measure media plurality need to be developed that enable taking into account the online world. Recently, Rupert Murdoch has announced his bid to take over BSkyB in its entirety, and the Government has referred this bid to Ofcom to review it on plurality grounds.

Linked to the issue of ownership is the lack of editorial autonomy when it comes to the UK press. The self-regulatory system still has not been reformed in line with Leveson recommendations and significant issues remain in this area.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Jelena | Dzakula | Visiting Lecturer | University of Westminster | X |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Steven | Barnett | Professor | University of Westminster |

| Damian | Tambini | Associate Professor | LSE |

| Justin | Schlosberg | Associate Professor | Birkbeck University |

| Daniel | Wilson | Head of Policy | BBC |

| Maria | Donde | Policy official | Ofcom |

| Janet | Shields | Representative of a journalists association | British Association of Journalists |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Office for National Statistics (2016) ‘UK Perspectives 2016: The UK in a European context’, available at https://visual.ons.gov.uk/uk-perspectives-2016-the-uk-in-an-european-context/

[3] Office for National Statistics (2011) ‘Language in England and Wales: 2011’, available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/language/articles/languageinenglandandwales/2013-03-04

[4] Office for National Statistics (2013) ‘2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom’, available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census

[5] Office for National Statistics (2016) ‘UK Perspectives 2016: The UK in a European context’, available at https://visual.ons.gov.uk/uk-perspectives-2016-the-uk-in-an-european-context/

[6] Ofcom (2016) ‘Communications Market Report 2016’, available at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/26826/cmr_uk_2016.pdf

[7] Michael Bromley (2016) ‘Media Landscapes: United Kingdom’, report by the European Journalism Centre

[8] Advertising Association and WARC (2016) ‘The Expenditure Report’, available at https://expenditurereport.warc.com

[9] Ofcom (2016) ‘Communications Market Report’, page 53

[10] The Leveson inquiry is a judicial inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the British press following the News International phone hacking scandal, chaired by Lord Justice Leveson. A series of public hearings were held throughout 2011 and 2012. The Inquiry published the Leveson Report in November 2012, which reviewed the general culture and ethics of the British media, and made recommendations for a new, independent, body to replace the existing Press Complaints Commission. Further details about the Leveson inquiry can be found at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140122145147/https:/www.levesoninquiry.org.uk/