Author: Yasemin Inceoglu, Ceren Sozeri, Tirse Erbaysal Filibeli (Galatasaray University)

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016, under a project financed by a preparatory action of the European Parliament. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research is based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF.

In Turkey, the CMPF partnered with Yasemin Inceoglu, Ceren Sozeri and Tirse Erbaysal Filibeli who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

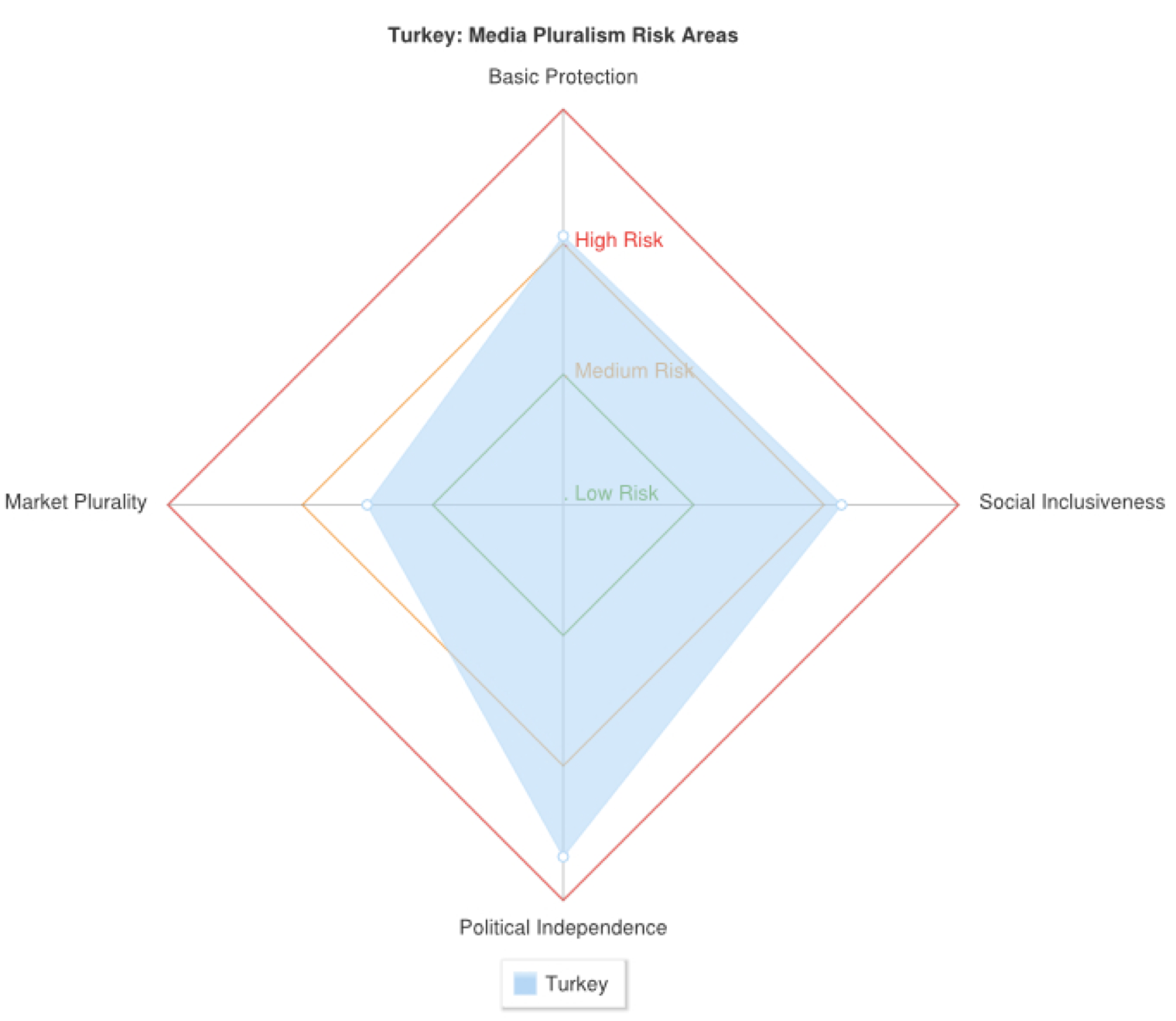

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Turkey obtained the status of European Union candidate country in 1999 and accession negotiations started in October 2005. The government has adopted some progressive legal reforms such as the right to information act, and the right to broadcast languages traditionally used by Turkish citizen in their daily lives in accordance with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) standards since 2004. However, as pointed out in 2014 and 2015 ECHR Progress Reports on Turkey, serious backsliding has been observed on freedom of expression and press both online and offline. The Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, Nils Muižnieks pointed out the concerns regarding the restrictive policies over freedom of expression and media freedom particularly risen after the 15 July coup attempt[2].

The country has a population of about 78 million as of 2016. The official language is Turkish. Even though the country is not socially and culturally homogeneous, only Armenians, Greeks and Jews are recognized as ethnic minorities regarding to the Treaty of Lausanne. The largest religious minority Alevis is not recognized in the regulations. Since 1965, there is no official data on the size of the minority population in Turkey. The research of the private agency KONDA (Research and Consultancy) entitled “The Social Structure in Turkey” in 2006 gives detailed information about the estimated population of minority groups and indicates Kurds as the largest minority group.

Not only in press freedom and minorities’ rights, the country has been in a political crisis last few years. On July 15, 2016, a military coup has been attempted. Soldiers and tanks moved into key positions around Istanbul and Ankara, people poured into the streets and 248 of them were killed. On July 20 2016, the President Erdogan declared a three-month state of emergency (then extended by 90 days) and partially suspended the European Convention on Human Rights. Since then, the Turkish government can rule by decree and can pass bills that have the force of law. As of today, more than 70 thousands civil servants were dismissed and more than 56 thousands were suspended on the grounds of orchestrating the failed coup. According to BİA Media Monitoring Report 2016, the number of journalists are behind the bars rose from 31 to 131, a record high for the last five years[3].

The economic situation also leads to a new crisis. The economic growth recorded the lowest rate of last decade. The Turkish lira fell to a new record day by day against the US dollar. Recently, the prominent credit rating agencies downgraded the country’s credit ratings due to raising risk premium. Besides, the government threatened frequently to hold a referendum on whether to continue EU membership negotiations due to the critics on human rights violations in the EC’s annual Progress Report. This, despite that the largest (48.5%) export share goes to the EU countries.

The expected economic crisis could dramatically affect media markets which currently have no satisfactory advertising revenue. Even though advertising revenues have the potential to increase further, their ratio to GDP remains around 0.3 – 0.4 i.e. the pie is far from being large enough.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Over the past years there has been a serious deterioration in press freedom in Turkey and the crackdown of media has worsened after the failed coup attempt on July 2016 . About 179 mostly Kurdish / pro-Kurdish media outlets were shut down by decree law no.668. This decree allows the government to close TV and radio stations on the grounds of alleged relations to terrorist organizations or threats to national security without a court order. Moreover media’s property can be confiscated by the state. As of April 2017, 157journalists are in jail[4], and 778 press cards and the passports of 46 journalists were cancelled by the government[5]. Tens of thousands of websites have been blocked by Telecommunications Communication Presidency. Criticism and journalistic activities can be criminalized through a wide interpretation of the Penal Code and the Anti-Terror Law.

Horizontal solidarity among journalists is very weak, the union rate is about 3%. Therefore, the professional associations and the unions are ineffective in guaranteeing editorial independence Self-censorship is very widespread in the media due to the owners’ dependence on the government and the mutual interests between them.

The composition of the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) has also been criticized for the selection and appointment process of the members and political interference. RTÜK does not ensure transparency of actual ownership structures and market shares of media companies. In addition, minority media and dissident media have had unequal access to official press advertisements[6].

In 2004, a new amendment allowed broadcasting in minority languages; however, the minorities still do not have proper access to media. On PSM channels, the content is controlled by the government. The PSM Turkish Radio Television Corporation (TRT)functions as a state-media far away from being a public service media.

The media literacy “elective course” is not taught by experts but by schoolteachers that only aims to protect children from the harmful effects of media contents.

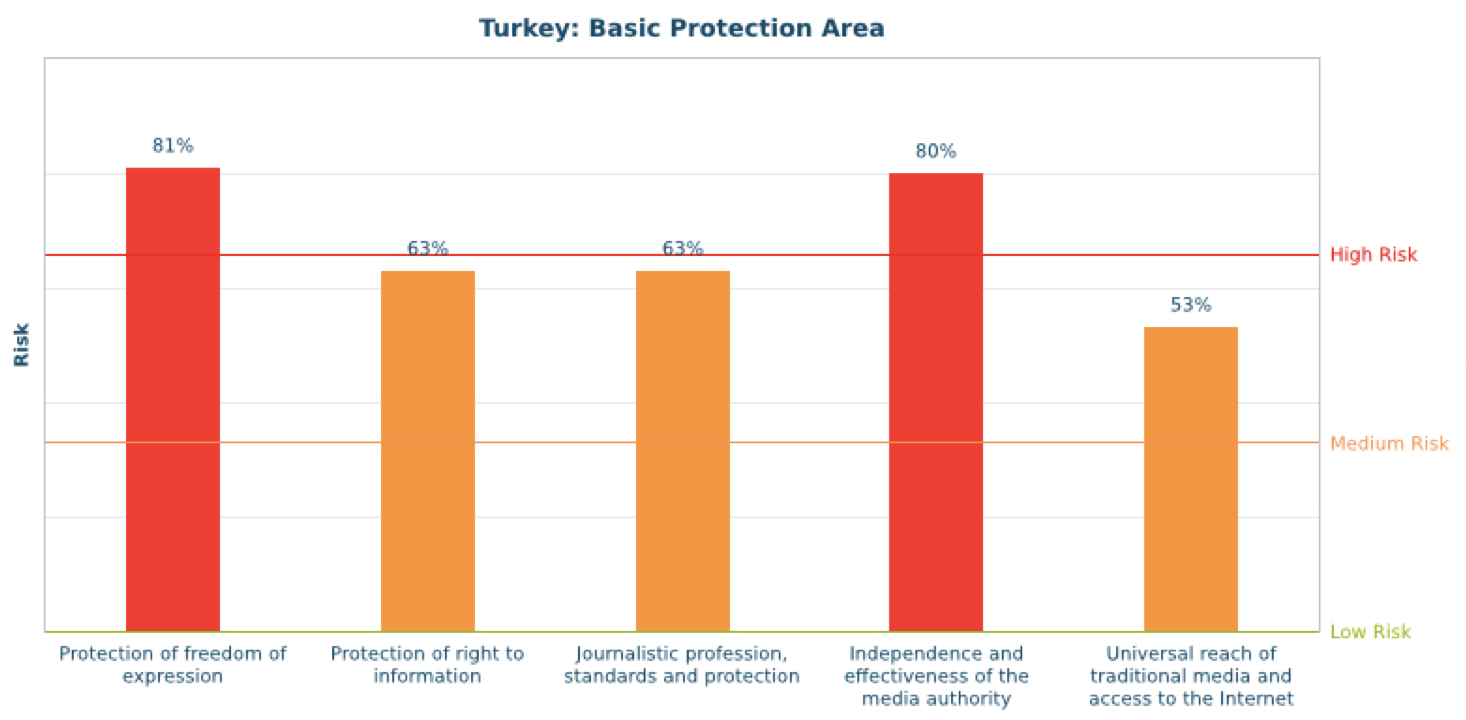

3.1 Basic Protection (68% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The indicator on Protection of freedom of expression scores a high risk (81%). While the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey (Articles 26, 28) guarantees respectively freedom of expression and of the press, criticism and journalistic activities are criminalized through widely interpretation of Penal Code and Anti Terror Law. These laws restrict freedom of expression and are not in line with European standards. In its progress reports, the EU pointed out significant backsliding in the past years in the areas of freedom of expression, due to restrictive interpretation of the legislation, political pressure, dismissals and frequent court cases against journalists which also lead to self-censorship[7]. Based on the latest data from April 12, 2017, at least 157 journalists are kept in jail[8]. According to ECtHR’s annual activity report, Turkey was the subject of the highest number of judgments regarding violations of freedom of expression in 2015[9]. In order to reduce the large number of applications to the ECtHR, a new constitutional amendment in 2011 gave the citizens the right to apply to the Constitutional Court in the case of an abuse of their constitutional rights.

The number of cases awaiting prosecution for “insulting” President Erdoğan had reached 1,845 as of 2 March 2016.

Today, tens of thousands of websites, most of them independent and/or Kurdish online news sites have been blocked by Telecommunications Communication Presidency (TİB). In 2012, the ECtHR decided that Article 8 of Internet Law No.5651 that regulates access bans on the Internet “failed to meet the foreseeability requirement under the Convention”. Nevertheless, the Parliament passed amendments to Internet Law No.5651 that strengthened the powers of the TİB to remove and/or impose an access ban on online content in 2014 and 2015.

After the failed coup attempt on July 15, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared a three-months state of emergency, then extended by 90 days, which allows the power to rule by decrees and suspended the European Convention on Human Rights as of July 20, 2016. Within the second decree, 16 television channels, 23 radio stations, three news agencies, 45 daily newspapers, 15 magazines and 29 publishing houses have been ordered to shut down regarding to the relationship with “Gulen Movement”, which is identified as terrorist organization FETO/PDY (Gulenist Terror Organisation/Parallel State Organisation) by Turkish National Security Council. As of November, the media outlets that were shut down increased 160 with the addition of pro-Kurdish ones.

The indicator on Protection of right to information scores at the top of medium risk (63%).The Law on Right to Information No.4982 came into force in 2004 which contains many exemptions including secrets, economic interests and intelligence activities of the state. Administrative and judicial investigations and prosecutions are not based on clear definitions of what “state secret” and “commercial secret” are.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection shows medium risk (63%) Horizontal solidarity among journalists is very weak, the union rate is about 3%, therefore, the professional associations and the unions are ineffective in guaranteeing editorial independence. The press cards are distributed by the Directorate General of Press and Information of the Office of the Prime Ministry and used as accreditation tool against journalists. The government is targeting journalists directly by excluding parliamentary reporters and the Ankara representatives of “dissident” media outlets[10]. In August 2015, The Journalists Association of Turkey (TGC) and Journalist Union of Turkey (TGS) withdrew from the government’s Press Card Commission after a controversial new regulation, which cancelled the accreditation of two press unions and reduced the TGS’s number of representatives in the Commission from three to one and selective dissemination practices. Recently, following the July 15 coup attempt, 778 press cards were cancelled[11].

The indicator on Independence and effectiveness of the media authority scores a high risk (80%). The composition of the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) has also been criticized for the selection and appointment procedures of the members and political interference. There is no independent representative of media associations, trade unions, academia or audience to strengthening of independence and professionalism of the regulatory body.

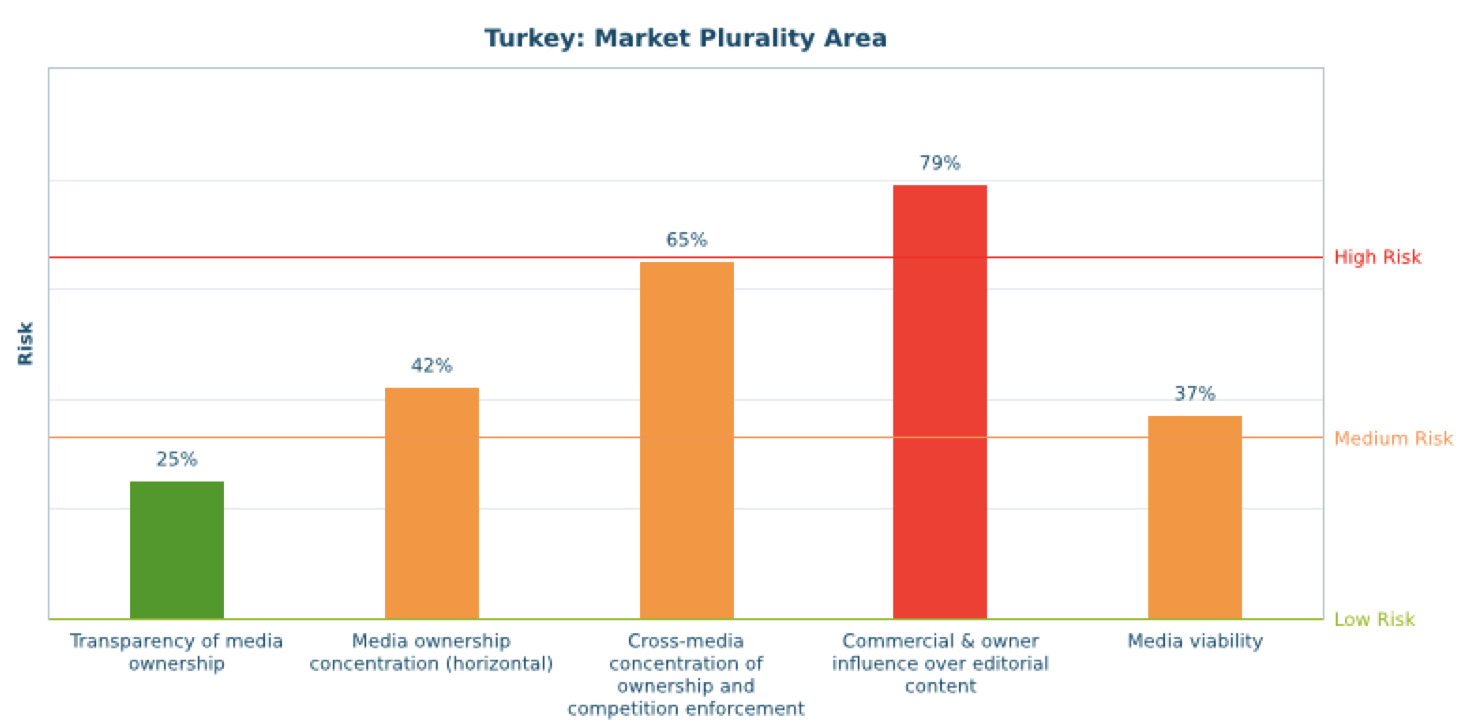

3.2 Market Plurality (50% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a low risk (25%). The Law No.6112 on the Establishment of Radio and Television Enterprises and Their Media Services obliges the media companies to notify their identification details to RTÜK and make them available on their web sites. However, without the shareholders’ information, these details do not ensure transparency of actual ownership structures of media companies.

The indicator on Media ownership concentration scores a medium risk (42%). Even though, the share of commercial communication, advertising revenues and other sponsorships are regarded as criteria for protecting competition and preventing monopolisation in the media market by law No.6112. RTÜK is responsible for overseeing limit excess but so far has not published any information on market shares – the law which empowered RTÜK to do that entered into force in 2012. The request of information on market shares – based on the Right to Information Act in 2015 – was denied on the grounds of “trade secret”[12]. Newspaper circulation numbers are shared by two distribution companies who dominate the market without independent audit.

The indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement scores at the top of medium risk (65 %). A large portion of advertising revenue feeds the audio-visual sector and most newspapers cannot generate optimal advertising revenues. The political pressure and rewards system via some incentives in massive state projects further encouraged some large businesses to involve into the sector.

The indicator on Commercial & owner influence over editorial content shows a high risk (79%). Under the high concentrated market structure, journalists’ job security remains unprotected. The high informal employment rate in the profession allows media owners to force journalists to sign contracts under Labour Law (No.4857) instead of Journalists Labour Law No.5953. Besides, horizontal solidarity among journalists is very weak what has resulted in a high level of dismissals.

The indicator on Media Viability scores a medium risk (37%). According to the Association of Advertising Agencies, TV and online advertising are consistently raising while the newspapers is in decline last few years. Audiovisual sector took more than 50 % from total advertising revenues[13]. Crowdsourcing is sometimes used by independent and small media outlets, however, it’s hard to develop new sources of revenue for these financially weak news organizations under economic pressure of the government.

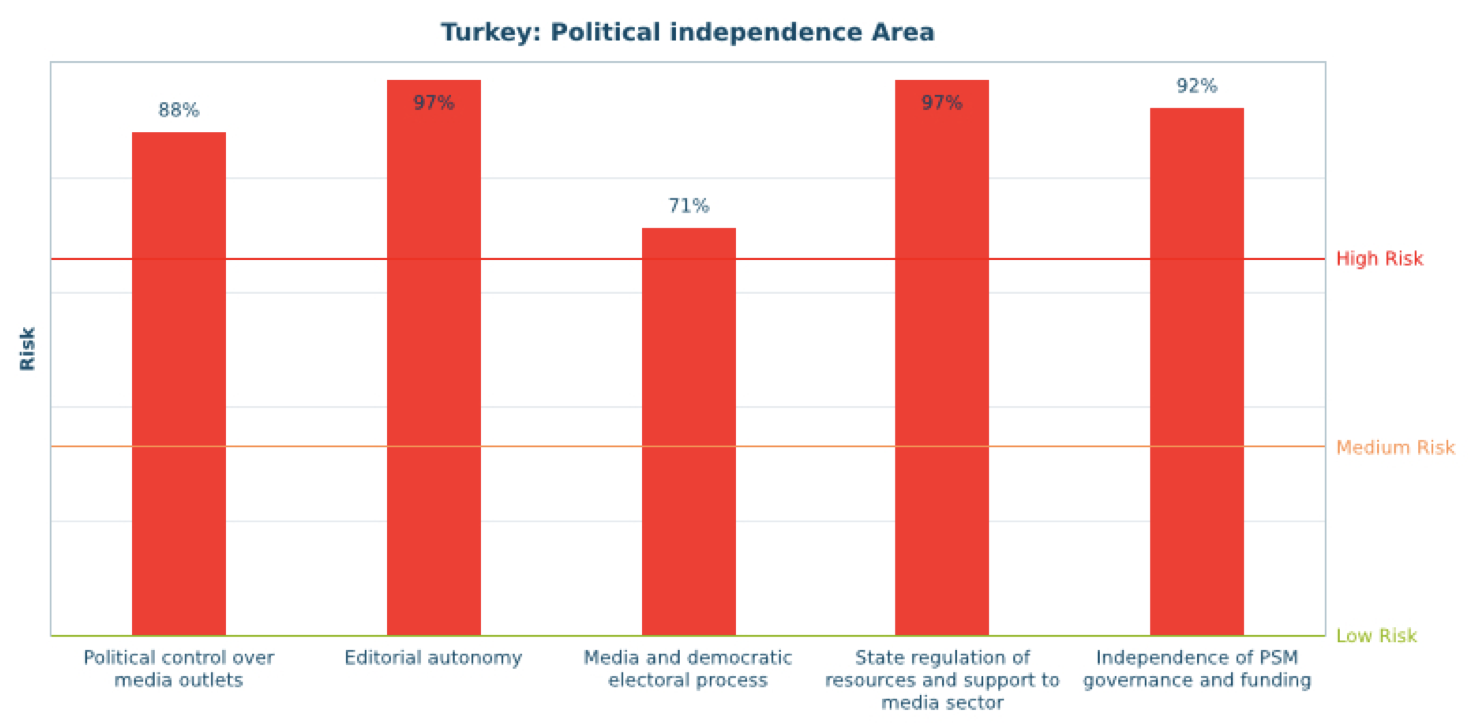

3.3 Political Independence (89% – high risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicator on Political control over the media outlets scores a high risk (88%). Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Bianet “Media Ownership Monitor” (MOM) research 7 of 10 most watched TV channels, 7 of 10 most read dailies, 5 of 10 most read news portal are belong to politically affiliated media companies[14]. Last November, a number of TV channels, pro-Gülen Movement and in March 2016 İMC TV were dropped from the state-owned Satellite Company (Türksat) and private platforms by the pressure of the government. This censorship was also criticized in Turkey Progress Report 2015[15]. A week before the last election Gülen Movement’s radio-TV channels and newspapers were seized and turned into the proponent media outlets by the government.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a highest risk (97%). The self-censorship is very widespread in the media due to the owners’ dependence on the government and the mutual interests between them. A high percentage of journalists believe that there both censorship and self-censorship exist in the media in 2013[16]. The Journalists Union of Turkey (TGS) stated that 10 thousands journalists (almost one-third) are jobless for five years; three thousands of them lost their job after coup attempt on 15 July 2016.[17]After the 15 July coup attempt, self-censorhip is alarming in the country. Many journalists have left the country. Former Cumhuriyet editor in chief Can Dündar and the paper’s Ankara representative Erdem Gül were imprisoned for 92 days after their stories on Turkish intelligence trucks bound for Syria were published in early 2014. Later, Dündar was attacked in an attempted shooting outside a courthouse in Istanbul on May 6 2016. The gunman was released after five-and-a-half months in jail. The International Press Institute’s Online project has since January 2016 monitored coordinated online campaigns by supporters of the ruling AKP Party and affiliated trolls to silence critical reporting in Turkey.[18]. The ideological polarizations and political divisions within and among various media and journalists’ associations abolished the credibility of media accountability and self-control mechanisms in Turkey.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores also a high risk (74%). The Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT) Law no.2954 guaranteed satisfying broadcasting to inform public opinion and forbid to one sided, partisan broadcasting and being an instrument to a political party, an idiological or belief interest group. The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Limited Referendum Observation Mission (OSCE/ODIHR LEOM) media monitoring findings showed that majority of television stations,including the public broadcaster, favoured the ruling party (AKP) in their programmes during the last election[19]. TRT has operated as the government’s propaganda tool. According to an opposition party, HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) Deputy Ersin Öngel, member of RTÜK, during a 25-day period that ended on October 27 2015, AKP received 30 hours of coverage, CHP (Republican People’s Party) garnering five hours and the MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) just one hour and 10 minutes. The HDP trailed with only 18 minutes of coverage.

Recently, a constitutional referendum which changes parliamentary system of government with a presidential one was made under the state of emergency on 16 April 2017. Private TV channels monitoring function of the Supreme Election Board (YSK) was ceased during the referendum campaign by a decree on 9 February 2017.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector is the second one in this area that scores a highest risk (97%). There is no direct subsidies to the media in Turkey. The public announcement and official advertisement (advertising paid by governments and state-owned institutions and companies) which distributed by The Directorate General of Press Advertisement (BİK) are important sources of revenue for small, independent and local press. Last few years it is observed that the big share of official advertisements went to pro-government media[20]. Last year, BİK refused to answer a freedom of information request by MOM to disclose advertising handed out to newspapers in the past 12 months, claiming this information was a “trade secret”[21]. BİK functions as a public body with the power to prohibit any publication that it deems to have violated media ethics from receiving advertising, leading to a censorship effect among the print media. On October 5th; an amendment came into force on bylaw of BİK which indicates that a newspaper that not fire journalists who are tried under The Anti-Terror Law within five days will also not benefit from official advertisements. Minority media and dissident media have had unequal access to official press advertisements.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding scores high risk (92%).TRT (state TV channel) was defined as an “impartial public legal entity” in the Constitution. However, the law on the appointment procedures of Board members and Director General does not guarantee independence from government or other political influence. The Director General is appointed for a four-year term by the Cabinet of Ministers among three candidates nominated by RTÜK. The main revenue of PSM, TRT is coming from the broadcasting (licence) fee generated from the sale of television and radio receivers, music sets and VTRs; 2% of electricity bills paid by each consumer; and a share allocated from the national budget. Due to lack of autonomy and the government interference with its budget, TRT has functioned as a state owned institution propagating the ruling parties policies.

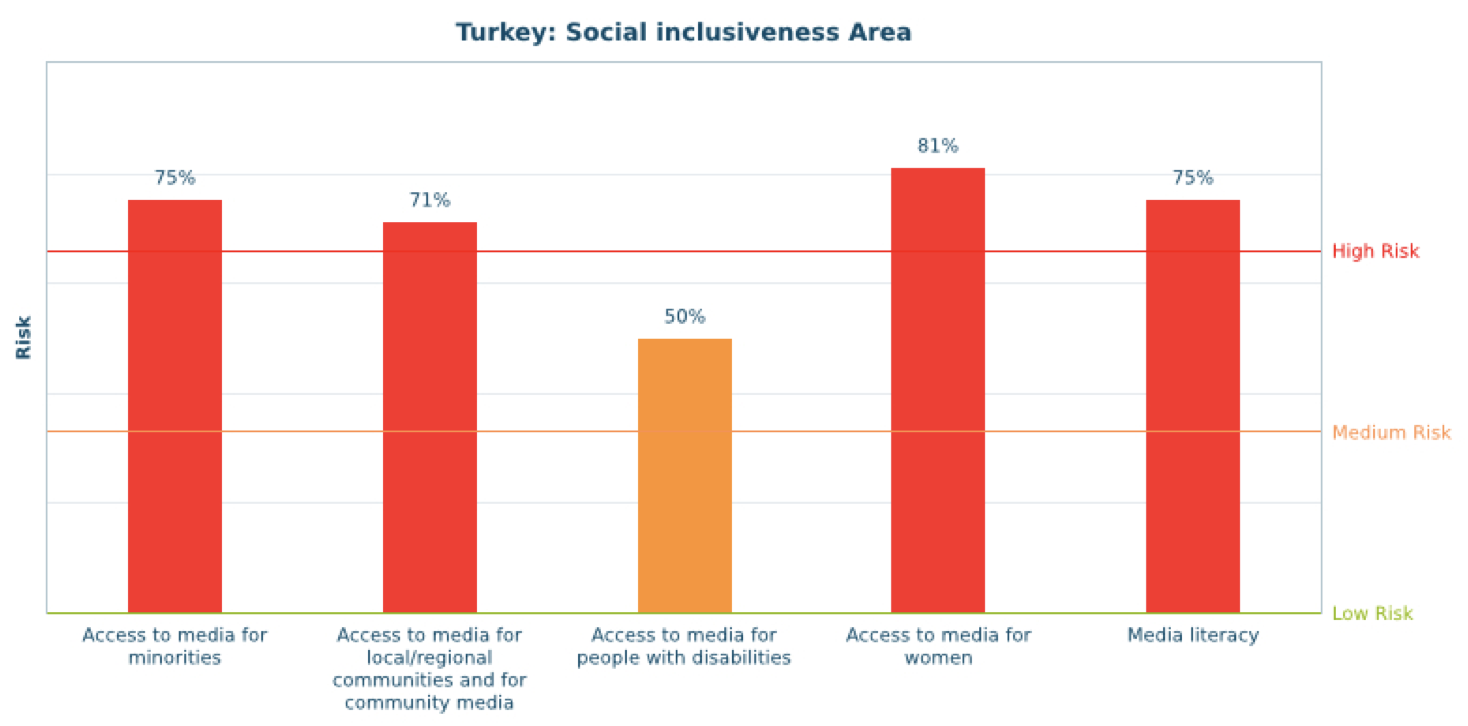

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (70% – high risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator on Access to media for minorities scores high risk (75%). According to the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey only recognizes Armenians, Greeks and Jews as ethnic minorities. There is no exact data concerning the different ethnic groups in Turkey since 1965 population census. On the other hand there are some research on ethnic and religious minorities in Turkey. According to Konda’s Social Structure Survey 2006, Alevis (5,73% of population) constructed the largest religious minority and the Kurds and Zazas (15.7% of population) constructed the largest ethnic minority in Turkey. However, they are not recognised as legal minorities. Broadcasting in other minorities’ languages has been banned for years. However, in 2001 constitutional amendments removed the restrictions on the utilization of ‘language prohibited by law’ in expressing and disseminating ideas in media. Moreover, in 2004, a new regulation allowed private broadcasting in minority languages at the national and local level.

Access to media for minorities represents high risk (75%). It’s because, the law does not guarantee access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities and most of the minorities do not have adequate access to airtime in practice. In January 2004, Regulation on Broadcasting in Traditionally Used Languages that came into force, allows both private national TV channels and PSM to broadcast in different languages. However, the regulation includes restrictive clauses on broadcasting some specific TV programmes as news, cartoon, TV movies etc. Besides, according to TRT Law No.2954 (Article 21), PSM can broadcast in local languages and dialects. In practice, the PSM TRT broadcasts regularly scheduled programmes in 31 languages over short wave transmitters and satellites, and trt.net.tr and trt.votworld.com web pages are available in 41 different dialects and languages. Although PSM broadcast in so many languages and dialects media content is still controlled by the state.[22]

In terms of proportionality of access to newspapers, as well as to airtime on TV and radio by minorities, there is a lack of data that impedes a rigorous assessment. However, the minority expert consulted by the country team stressed that minority groups in Turkey do not have proper access to public or private media. Moreover, after the failed coup attempt in 2016, the government has used the state of emergency and shut down several TV channels, including a channel belonging to the religious minority Alevis.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores high risk (71%). The law No.6112 (Article 3) grants regional and local media access to media platforms. The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) is tasked with allocating licenses and permits for terrestrial, satellite and cable broadcasting; supervising broadcasting content; and imposing sanctions. Under the previous law no.3984, RTÜK imposed heavy sanctions against dissident and minority media and suspended the broadcasting of local, regional and national operators thousands times (The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) Sectoral Report 2014: 17).[23] The new law No.6112 diversified “Principles for Media Services” (Article 8) to reduce suspension penalties and took into consideration “coverage area” to prevent unfair sanction implementing. In practice, even though implementation of law no. 6112, there still are unfair sanctions against community media.

The constitutional law in Turkey grants community media access to media platforms. At the same time, community media is mostly based on the web in Turkey. In 2014, the Internet Law No.5651 was amended, broadening the scope of administrative online blocking and allowing the authorities to access user data without a warrant. The community online news outlets are constantly blocked by Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK). Since September 2014, over 110,000 websites were banned based on civil code–related complaints and intellectual-property rights violations (engelliweb.com).[24] As it is mentioned in Freedom House’s Freedom on The Net Report 2015, the number of blocked websites has risen from 43,785 to 81,525 in two years. This figure includes numerous sites that belong to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) communities, ethnic minorities etc. Additionally, in Turkey the radio- television law no. 6112 regulates only commercial media and despite the amendment of The Directorate General of Press Advertisement (BIK) (2012) community newspapers cannot get official advertising revenue. Besides, according to a new regulation of BIK, which came into force on October 5 2016, article 39 indicates that newspapers should be published in Turkish for getting subsidies from the Directorate General of Press Advertisement.

The indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk (50%). It shows that existing regulation on Broadcasting Principles and Procedures not efficient. According to the amendment came into force on April 3, 2014, PSM Channels (TRT) should add subtitles to 35% of TV programmes in three years, in five years subtitled TV programmes should be increased to 50%. Besides, private national TV channels should broadcast 25% of TV programmes with subtitles in three years and in five years subtitled TV programmes should be augmented from 25% to 40%. This regulation doesn’t include specific article on audio-description. Nowadays, in Turkey PSM, pay TV services and some private channels have websites and services for people with disabilities. However, websites lack subtitles, translation with sign language and audio description. Unless it has been three years since the implementation of the regulation , most of the TV channels still doesn’t have any subtitled TV programmes.

The indicator on Access to media for women scores high risk (81%). The Constitution (Article 10) and The Turkish Labor Law 4857 (Article 5) grants equal rights for employment of women. However, there are no women on the PSM’s Board of Directors. According to Global Media Monitoring Project 2015 Report in Turkey just 19% of the people on the news and 17% of the reporters are women.[25]

The indicator on Media Literacy shows high risk (75%). In the RTÜK law 6112 (Article 33), media literacy is defined as one of the RTÜK’s duties. RTÜK collaborates with the other public institutions, particularly with the Ministry of National Education (MEB) on media literacy. MEB has developed the part on media literacy in the education curriculum, which mainly focuses on training of children on utilization of media and protecting them from the harmful effects of media contents. As it is seen there is no policy on the development of digital skills of students. Another problem about media literacy in Turkey is about the quality of media literacy course teachers. One possible initiative in that area could be the establishment of a cooperation between the faculty of communication in Turkey – which has more than 30 thousands graduates from more than 50 faculties across the country – and the primary school education system. Such potential workforce could be used either as teachers in the system or to provide teacher training programs and to design teaching materials regarding media literacy. [26]

4. Conclusions

Turkey leads the ranks of the worst countries for press freedom nowadays[27]. The number of imprisoned journalists reached the highest level, at least 157, after the failed coup attempt. At least 179 media outlets were shut down. Tens of thousands of websites, most of them independent and/or Kurdish online news sites have been blocked by Telecommunications Communication Presidency (TİB). Anti-terror Law and the Penal Code have excessively cracked down on journalists. The number of cases awaiting prosecution for “insulting” President Erdoğan had reached 1,845 as of 2 March 2016. Urgently, the government should stop criminalizing journalism and abolish Articles 299 and 301 in the Penal Code which regulate crime of “insulting the president,” and “insulting Turkishness”.

Journalists are unprotected against the government and media owners. The journalists’ associations, trade unions should strengthen horizontal solidarity to struggle with political or economic interference to the editorial independence and to protect media pluralism by creating a platform for journalistic debate, providing legal and financial supports for prosecuted, jailed journalists. They should develop international cooperations to raise awareness of media freedom issues in Turkey. The also should promote journalists to create independent, credible and effective national systems of self-regulation.

The preselected media bosses serve the government through the news contents for their economic benefits. The government stop to use some economic tools such instance seizing media outlets to reconfigure the media environment.

The dissident media and critical journalists have faced with overwhelming attacks and sanctions. The government should safeguard the independence of media authority and redesign it with the participation of journalist associations, media representatives, academics and audience. The media authority should be transparent and ensure accurate and up-to-date data on media ownership and market concentration.

The minorities in Turkey still do not have proper access to media, not even to PSM channels. The government should ensure autonomy of PSM and protect its editorial independence safeguard and subsidize the community, regional and local media. TRT should be transformed into a truly public service broadcaster with a supervisory body which is representative of society at large and protected against political and financial interferences by law. It’s obviously needed to develop policies on gender equality in media sector and protect the rights of female employees.

Annexe 1. Country Team

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Yasemin | İnceoğlu | Galatasaray University | X | |

| Ceren | Sözeri | Galatasaray University | ||

| Tirşe | Erbaysal Filibeli | Bahçeşehir University | ||

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

Any country-specific deviation from the standard Group of Experts procedure should be briefly explained here.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Yonca | Cingöz | Representative of a publisher organisation | Turkish Publishers Associations |

| Yaman | Akdeniz | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Bilgi University |

| Gülsin | Harman | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | International Press Institute |

| Ferhat | Boratav | Representative of a broadcaster organisation | CNN Türk |

| Erol | Önderoğlu | Representative of a journalist organisation | Reporters Without Borders Turkey |

| Emir | Ulucak | Representative of media regulators | The Radio and Television Supreme Council |

| Aslı | Tunç | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | Bilgi University |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] The data collection and the report does not reflect recent changes in the country. For more information about updated assessment of Council of Europe, see Memorandum on freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey, 15 February 2017, https://wcd.coe.int/com.instranet.InstraServlet?command=com.instranet.CmdBlobGet&InstranetImage=2961658&SecMode=1&DocId=2397056&Usage=2

[3] Erol Önderoğlu, BİA Media Monitoring Report 2016: Journalism Gripped by State of Emergency, 17 February 2017, https://bianet.org/english/media/183723-2016-journalism-gripped-by-state-of-emergency

[4] Tha data from the Journalists Union of Turkey (TGS), 12 April 2017, https://tgs.org.tr/cezaevindeki-gazeteciler/

[5] Erol Önderoğlu, BİA Media Monitoring Report 2016: Journalism Gripped by State of Emergency, 17 February 2017, https://bianet.org/english/media/183723-2016-journalism-gripped-by-state-of-emergency

[6] Dilek Kurban and Ceren Sözeri, “Policy Suggestions For Free and

Independent Media in Turkey”, TESEV Publication, 2013, https://tesev.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Policy_Suggestions_For_Free_And_Independent_Media_In_Turkey.pdf

[7] https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_turkey.pdf

[8] Tha data from the Journalists Union of Turkey (TGS), 12 April 2017, https://tgs.org.tr/cezaevindeki-gazeteciler

[9] European Court of Human Rights Annual Report 2015, https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Annual_report_2015_ENG.pdf

[10] Ceren Sözeri, “Turkey After an Attempted Coup the Journalists’ Nightmare”, in Ethics in the News EJN Report on Challenges for Journalism in the Post-truth Era, (ed.by) Aidan White, 2017, https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/resources/publications/ethics-in-the-news/turkey

[11] Erol Önderoğlu, BİA Media Monitoring Report 2016: Journalism Gripped by State of Emergency, 17 February 2017, https://bianet.org/english/media/183723-2016-journalism-gripped-by-state-of-emergency

[12]Ceren Sözeri, Türkiye’de Medya ve İktidar İlişkileri. Sorunlar ve Öneriler [Media and Power Relations in Turkey. Problems and Suggestions], Istanbul Enstitüsü, 2015, https://platform24.org/Content/Uploads/Editor/T%C3%BCrkiye%E2%80%99de%20Medya-%C4%B0ktidar%20%C4%B0li%C5%9Fkileri-BASKI.pdf

[13] Media Investments of Association of Advertising Agencies, https://rd.org.tr/medya-yatirimlari.html

[14] Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Bianet, “Media Ownership Monitor” (MOM), 2017, https://turkey.mom-rsf.org/en/findings/political-affiliations/

[15] European Parliament resolution of 10 June 2015 on the 2014 Commission Progress Report on Turkey, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P8-TA-2015-0228+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

[16]Esra Arsan, “Killing Me Softly with His Words: Censorship and Self-Censorship from the Perspective of Turkish Journalists”, Turkish Studies, Volume 14, Issue 3, 2013

[17] “Çalışamayan Gazeteciler günü” [The day of journalists cannot work], TGS, 10 January 2017, https://tgs.org.tr/calisamayan-gazeteciler-gunu/

[18] Ceren Sözeri, “Turkey After an Attempted Coup the Journalists’ Nightmare”, in Ethics in the News EJN Report on Challenges for Journalism in the Post-truth Era, (ed.by) Aidan White, 2017, https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/resources/publications/ethics-in-the-news/turkey

[19]Early Parliamentary Election 1 November 2015 OSCE / ODIHR Limited Election Observation MissionFinal Report, 28 January 2016, https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/turkey/219201?download=true

[20] T24, “4 ayda 13 milyonluk resmi ilanı hangi gazeteler aldı?” [Which

newspapers took 13 million offical ads in 4 months?], T24, 09 June 2014,

https://t24.com.tr/haber/4-ayda-13-milyonluk-resmi-ilani-hangi-gazeteler-aldi,260643

[21] Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Bianet, “Media Ownership Monitor” (MOM), 2017 https://turkey.mom-rsf.org/en/media/print/

Nurcan Kaya & Clive Baldwin, Minorities in Turkey Submission to the European Union and the Government of Turkey, Minority Rights Group International July 2004

[23] Radyo ve Televizyon Yayıncılığı Sektör Raporu RTÜK 2014.

[24] Engelliweb.com was a platform, which give statistical data on banned web sites. In 2017, Engelliweb.com was also banned.

[25] Who make news?, GMMP Report 2015, https://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/global/gmmp_global_report_en.pdf

[26] Nurçay Türkoğlu & Esengül Akyıldız, Media and Information Literacy Policies in Turkey, 2013,

https://ppemi.ens-cachan.fr/data/media/colloque140528/rapports/TURKEY_2014.pdf

Yasemin İnceoğlu & İnci Çınarlı, A critical analysis of Turkish Media Landscape for a better Media Literacy Education, https://www.yasemininceoglu.com/default.aspx?cat=4&pag=142

[27] Kürşat Akyol, “Turkey: ‘Worst country’ for media freedom in 2016”, DW, 27 December 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/turkey-worst-country-for-media-freedom-in-2016/a-36924382