Download the report in .pdf

English – Hungarian

Authors: Amy Brouillette, Attila Bátorfy, Marius Dragomir, Éva Bognár, Dumitrita Holdis

October 2016

1. About the Project

Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016, under a project financed by a preparatory action of the European Parliament. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF.

In Hungary, the CMPF partnered with researchers at the Center for Media, Data and Society at the School of Public Policy, Central European University in Budapest, who conducted the data collection, commented on the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

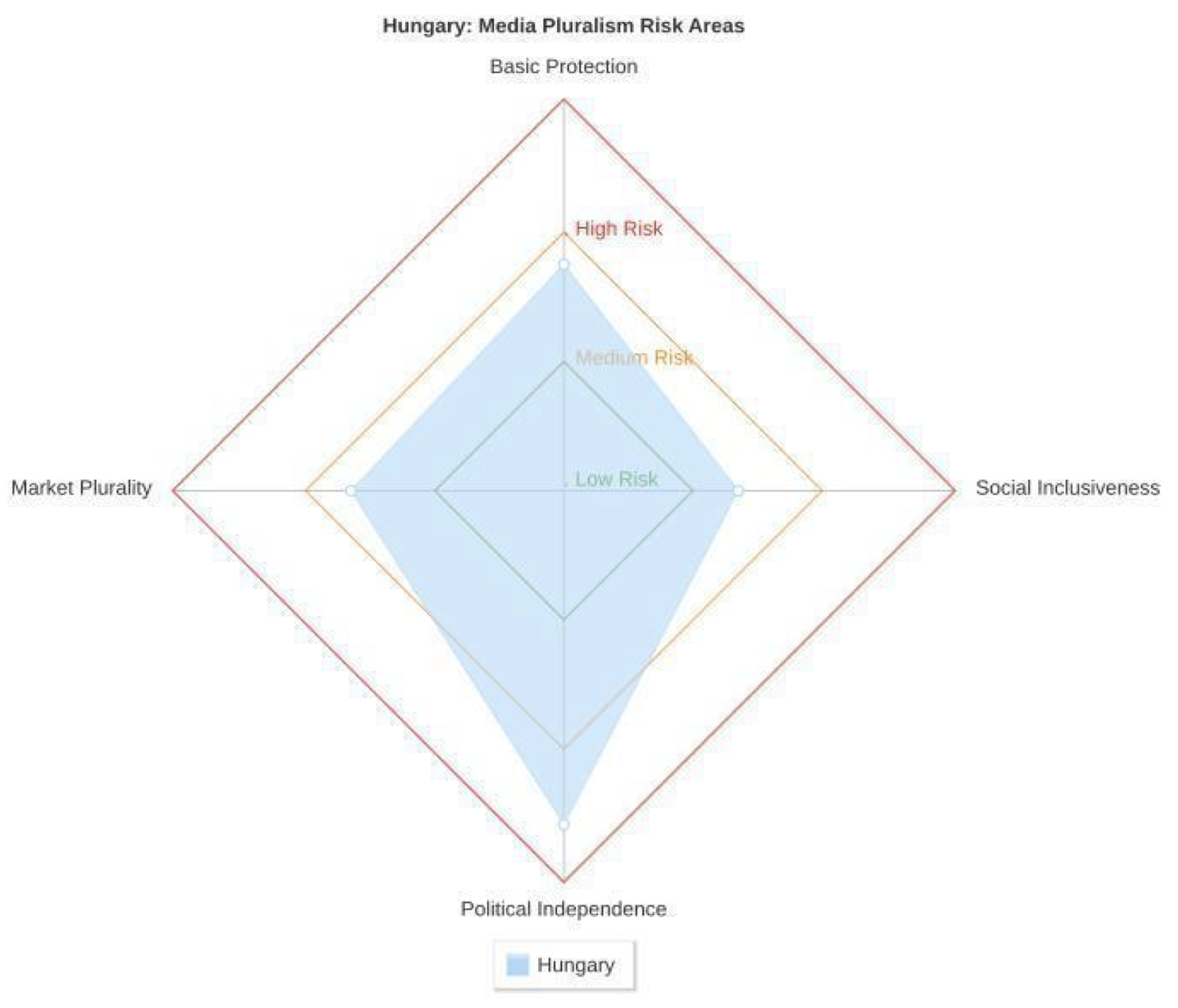

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women |

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk.[1]

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Hungary has a population of 9.830.000.² It is a mostly monolingual society with 99% of the population speaking Hungarian. The country is homogeneous from an ethnic point of view: according to the last census in 2011, just 1.7% claimed being of another nationality than Hungarian. The largest ethnic minority is the Roma, with 3.2% self-reported Roma in the 2011 census.[2] Hungary`s nominal GDP was approximately EUR 110 billion in 2015.[3] As to the political situation: Hungary is a parliamentary democracy with a coalition of two right-wing parties (Fidesz and KDNP) governing. In 2010, the current governing parties were elected to Parliament with a two-thirds majority, then re-elected in 2014. Electoral support for the left opposition is low with the proportion of undecided voters fluctuating between 35 and 45% of the population.[4]

The Hungarian media market consists of a mix of public and private media (with two national commercial television stations and a public service broadcaster). The market is characterized by a high level of political parallelism. Internet penetration is at 76%. Online news portals are important sources of information, but television is still the most important news source to many. Hungarians turn to social media, especially to Facebook when looking for news more often than others. Trust in media being free from political or business influence is extremely low.[5]

Regarding media regulation, the convergent National Media and Telecommunications Authority (NMHH) has oversight over the country’s electronic media, telecommunications and postal services.

3. Results from the Data Collection: Assessment of the Risks to Media Pluralism

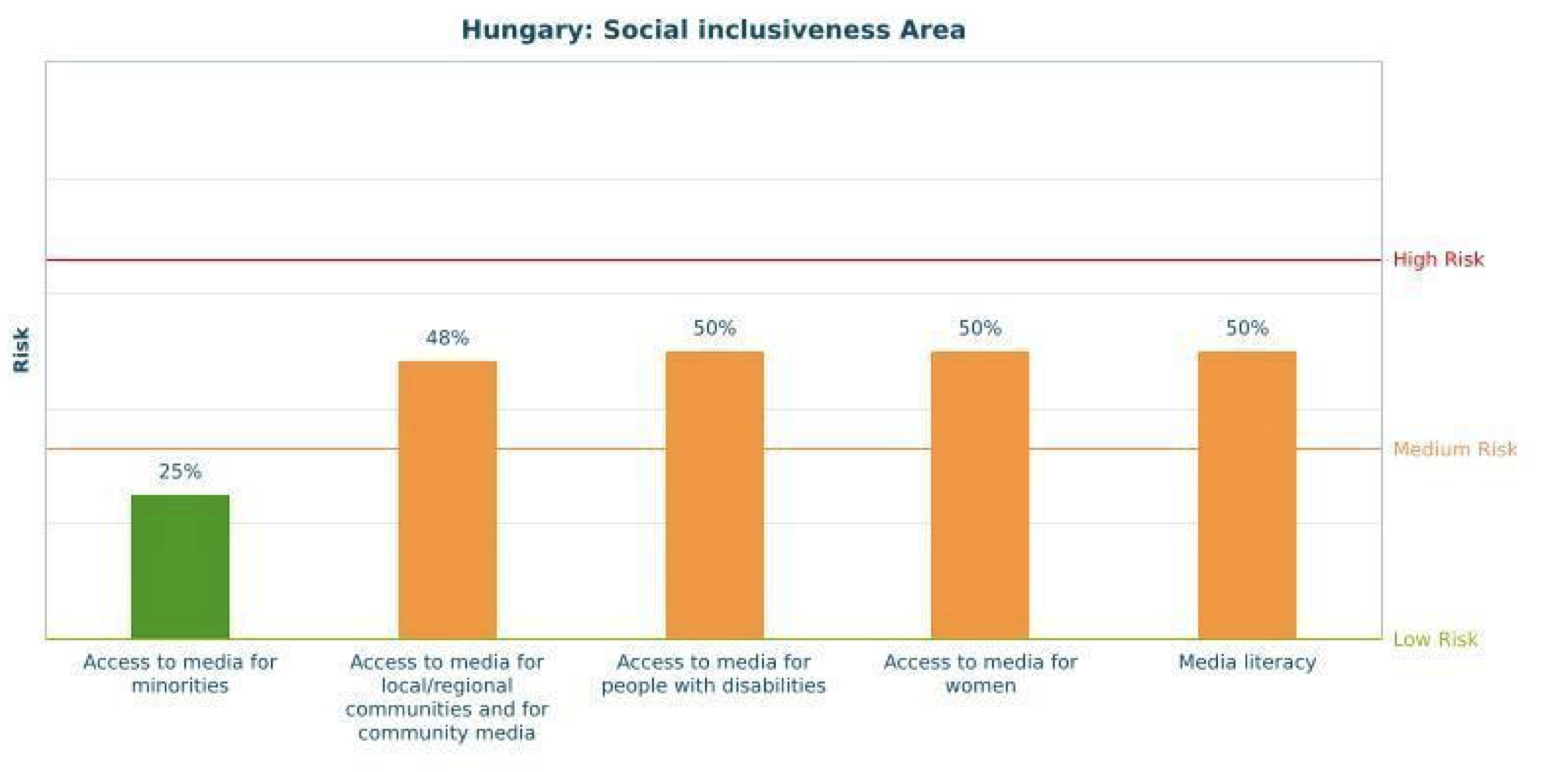

Risks to media pluralism in Hungary are high. Social inclusiveness risk scores are the lowest and political independence indicators score the highest risk.

The Hungarian constitution and the 2010 media laws have been heavily criticised nationally and internationally, although formal protections to media pluralism are in place with certain elements of protection lacking.

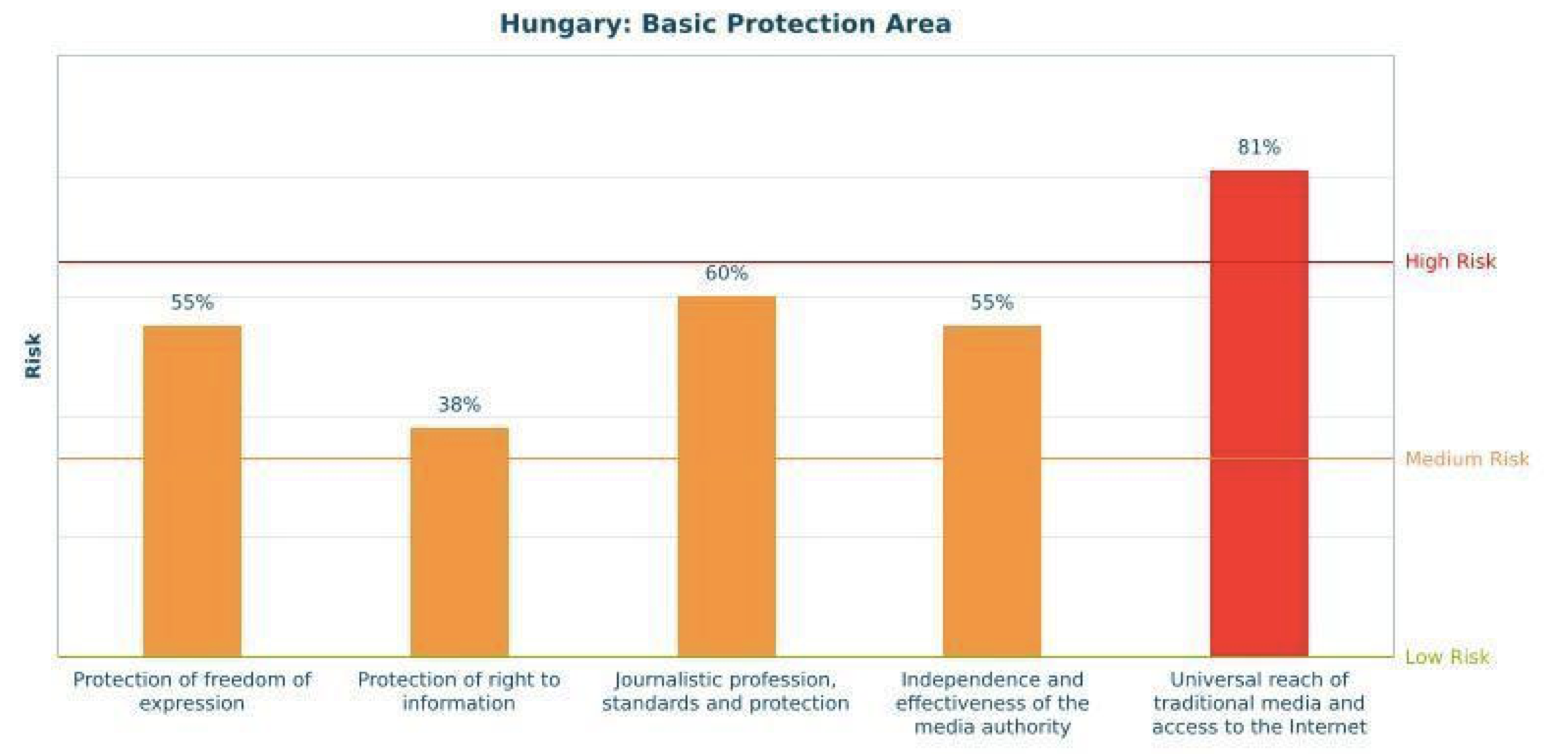

Indicators in the area (namely protection of freedom of expression and of right to information, standards and protection of journalistic profession and independence and effectiveness of the media authority) score at medium risk, with the indicator on Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet presenting the highest risk within the Basic Protection area as universal access for Public Service Media (PSM) is not specified in media regulation.

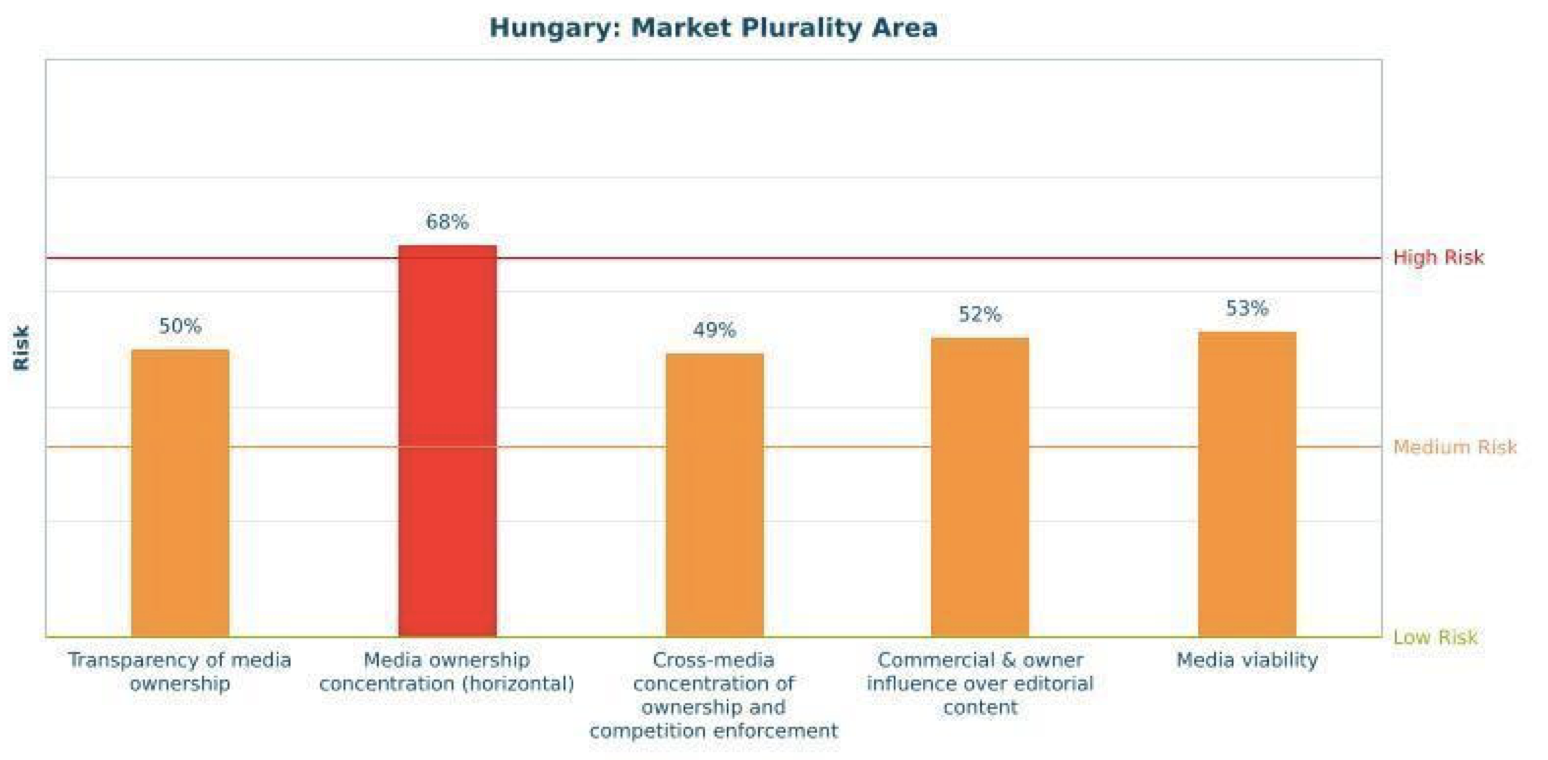

With regards to Market Plurality, indicators on Transparency of media ownership, Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement; Commercial and owner influence over editorial content; and Media viability all pose medium risks. Horizontal media ownership, on the other hand, poses high risk due to structural deficiencies in the law and lack of an independent regulator to ensure fair market competition.

The Political Independence indicators score high risk. Every indicator in the area is in the high-risk zone, the highest risk being the state regulation of resources and support to media sector. This is mostly because of the lack of fair rules and transparency related to the distribution of state advertising. The indicator that scored the second highest risk in the area is the Independence of PSM governance and funding, but the other indicators (Editorial autonomy; Political control over media outlets; and Media and democratic electoral process) all scored at high risk as well. Political pressure on journalists, editors and media outlets (let it be related to the distribution of state advertising, the operation of the PSM or more concrete chilling practices by politicians) have been on the agenda in Hungary, so the area being in the high risk zone was to be expected.

The area of Social Inclusiveness poses the lowest risk to pluralism, according to the data. Within the area (and also within the whole survey), the Access to media for minorities indicator scores the lowest even though the only television programme or channel for Hungary`s biggest minority group (the Roma) is the weekly “Roma magazin” in the Hungarian PSM.

The remaining indicators in the area (Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media; Access to media for people with disabilities; Access to media for women; Media literacy) scored medium risk. It is important to consider, however, that even though the legal framework in most of these cases is satisfactory, practice is lagging behind: the media organizations providing representation for Roma-related news and trainings for Roma journalists, for example, are struggling because of financial hardships. Equal representation of women in the Hungarian media is a persistent problem.

3.1. Basic Protection (58% ‒ medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Freedom of expression is formally guaranteed in the Hungarian constitution and the 2010 media laws.[6] Hungary ratified all major international conventions addressing freedom of expression including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights (1992). However journalists in Hungary are bound by criminal and civil defamation and libel laws. Under the criminal code, media are subject to increased punishments and liability for offenses,[7] which have an acute chilling effect on the media. For that reason the indicator on Protection of freedom of expression scored a medium risk (55%).

In what concerns the indicator on Protection of right to information, while the right to access public information is explicitly recognised in the Constitution and in national legislation, recent measures are weakening these legal safeguards. Hungarian lawmakers in 2011 introduced a new regulatory framework (and supervisory body), with the “Act CXII. of 2011 about information self-determination and freedom of information.” This law created a new authority, the National Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority (NAIH), responsible for overseeing compliance with the legislation. Importantly, the former data commissioner (a strong proponent of freedom of information) was dismissed, stirring much public controversy.

A 2013 amendment introduced new restrictions on access to information and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests in Hungary, which have curtailed the former scope of the law and limited the public’s and media’s ability to request public information. The amendment was introduced by lawmakers in response to the number of freedom of information lawsuits filed by investigative journalists seeking information on public media spending (among other data). The amendment has been heavily criticized by media outlets and NGOs for imposing undue restrictions on access to public data.

The current government has also created obstacles to freedom of information requests. Such requests include public access to information about key development projects, including the construction of the Paks II nuclear power plant, several stadiums, and a new museum quarter in Budapest. In all of these cases, the documentation for these projects was closed to the public and media, which is problematic as information about how public funding is spent should be transparent. For these reasons this indicator also reached a medium risk level (38%).

Regarding the indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection, access to the journalistic profession is open. Self-regulatory codes emphasize the independence of editorial content and other professional standards such as objectivity, although such standards are often not implemented in practice. Protection of journalistic sources is recognized by law and by the Constitutional Court. Following a Constitutional Court ruling, the media law is now in line with the Council of Europe’s Recommendation No. R (2000) 7, and only courts may oblige a journalist to reveal his or her sources and the case must be specifically justified.

Access to events for news reporting is not explicitly recognised by the law. The media legislation obliges the state, public authorities and institutions, state-owned enterprises and their leaders as well as public servants to help the work of journalists by providing them with timely information.[8] In practice, there have been cases in which journalists and/or media outlets have been denied necessary press credentials for accessing Parliament and/or election events. In addition, access to the plenary sessions of Parliament can be limited. Private television channels may not take footage of these sessions but can only purchase footage that is produced and distributed by a company specially commissioned by Parliament.

There are several professional journalist associations in Hungary, although their enforcement capacities remain weak. The major organization is the Hungarian Journalists Association (Magyar Újságírók Országos Szövetsége, MÚOSZ) with some 5,000 members. The organisation has a code of ethics and practice based on the standards of journalism (such as objectivity, neutrality, the separation of news from views etc.). The organisation also has an Ethics Commission which, however, does not have the means to enforce standards. In practice, however, partisan journalism is the rule in most of the print and broadcast media.

While MÚOSZ is commonly associated with left-wing journalists, there also are some minor journalists’ associations of right-wing journalists such as the Hungarian Journalists Community (Magyar Újságírók Közössége, MÚK) and the Hungarian Catholic Journalists Association (Magyar Katolikus Újságírók Szövetsége, MAKÚSZ). While the three organisations also have a joint code of ethics and of practice, co-operation between the three is lacking. There is also a Press Union (Sajtószakszervezet), whose ability to enforce journalists’ interests is, however, limited. Currently there is no collective contract protecting journalists’ rights vis-à-vis employers. This indicator shows a medium – almost high – risk level (60%).

Regarding the indicator on Independence and effectiveness of the media authority, the National Media and Telecommunications Authority (NMHH – the “Media Authority”) was established by Act 82/2010, the first major piece of legislation in the Hungarian government’s larger media law “package” passed by Hungarian lawmakers in July 2010. The law also established the Media Council, a body within the Media Authority, to monitor and enforce the set of new media laws passed by Parliament in November and December of 2010. The independence of the Media Authority and Media Council are formally specified in the Media Act. However, the appointment procedures do not provide adequate legal safeguards for independence in cases in which the government has a majority in Parliament (as is currently and often the case). Currently, all five members of the Media Council were nominated and elected by Fidesz, for nine-year terms. Amendments to these procedures passed in 2013 based on Council of Europe recommendations failed to provide sufficient formal safeguards ensuring the political independence of all appointees.[9] The modifications now require the president of Hungary to approve the prime minister’s nomination for the head of the Media Authority/Media Council, whereas previously the prime minister directly nominated this position. Thus, not much has changed in the power the government has over the appointments of the media council members. In addition, while rules of incompatibility and eligibility for members are specified in the media law, regulations have not ensured objective and transparent appointment procedures in practice. All that makes this indicator score a medium risk (55%).

The media law guarantees the existence of PSM in Hungary but universal access for PSM is not specified. All public service television channels are distributed via digital satellite and terrestrial broadcasting and can be accessed by more than 99% of population via DVB-T. The public service radio station MR1 Kossuth Radio has a 100% coverage over the country (also reaching some of the neighbouring countries), while the coverage of other public service radio stations is below that level (MR2 Petőfi Radio: 86%, MR3 Bartók Radio 68%, MR4 National broadcasting – for nationalities – 92%). The print media distribution system is controlled by two main actors, the privately owned company Lapker and the state-owned Magyar Posta, Hungary’s postal operator. Problems with the delivery of print media to small villages persist. Universal access for broadband (fixed line and mobile) has not been achieved in Hungary. Internet penetration in Hungary is over 60%. The indicator on Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet presented the higher risk within the Basic Protection area (81%).

3.2. Market Plurality (54% ‒ medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a medium risk (50%). While there are some legal obligations addressing public disclosure of media ownership, these mechanisms do not ensure ownership transparency in practice, particularly of “real” or ultimate beneficial owners. In Hungary, media ownership is often obscured through complex, multi-layered ownership structures as well as by the use of proxies and straw men. All business entities operating in Hungary, including media companies, are required to register with the Court of Registry. These records are available for free at the Court of Registry, or electronically on fee-based subscription through private companies. Public ownership records can reveal owners and shareholders, but often without indicating percentages of ownership and voting rights. For foreign owners and other corporate types — like holding companies — the names of shareholders or partners are not available in public ownership records. The 2010 Media Act also includes some reporting obligations of ownership by media service providers. However, more detailed records of internal ownership structures and shareholders are still not publicly disclosed. The former 1996 Act on TV and Radio required private national and regional TV, and national radio channels to operate in the form of a limited company the members of which are publicly available or in the case of a shareholding it required the company to issue only registered shares. This created a formal mechanism to ensure some level of transparency of ownership by preventing certain business entities from directly or indirectly obtaining broadcasting rights in Hungary. The 2010 Media Act contains no requirements anymore for what “type” of entity can operate such services, which reduces prior formal safeguards regarding market-ownership transparency.

Media ownership concentration (horizontal) scores a high risk (68%). The 2010 Media Act contains provisions limiting both horizontal and vertical concentration. In Hungary, a company may now operate numerous brands (channels or titles) in the same market sector, within the anti-concentration restrictions specified by the 2010 Media Act. However these provisions have not prevented market concentration in practice. This is both a result of structural deficiencies in the law and lack of an independent regulator to ensure fair market competition in line with principles and obligations to safeguard market pluralism. The audience share model comes from the German and the former UK media laws, the theoretical benefit of which is to increase media pluralism by limiting a media operator’s market presence once it reaches a certain level of audience penetration. However, the law does not specify clear remedies in cases in which an operator exceeds these thresholds.

Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement is at medium risk (49%). The 2010 Media Act introduced a new regulatory model regarding media concentration based on audience share that restricts market positions when stations reach a certain threshold. However, the law also removed prior restrictions on cross ownership.

The Hungarian Competition Authority (Gazdasági Versenyhivatal, GVH) is responsible for ensuring the proper functioning of the markets without improper competition practices or concentration occurring. The 2010 Media Act entitles the Media Council to intervene in a merger/acquisition approval procedure conducted by the competition authority in the cases where the provisions of the 2010 Media Act related to concentration in the media market apply. The position statement of the Media Council binds the Hungarian Competition Authority to consider and apply that position statement in determining the approval or rejection of the merger/acquisition. The Competition Authority cannot legally decide against or without the consent of the Media Council; however, the Media Act permits the Competition Authority to still disapprove transactions approved by the Media Council or to add more conditions to the transaction that the Media Council did not propose.

Commercial and owner influence over editorial content scores a medium risk (52%). Editorial content of news media in Hungary is heavily influenced by commercial factors and ownership ties. In Hungary, like in other post-socialist countries with limited audience and advertising markets, the media are frequently exposed to economic pressures. In recent years, the growing number of media outlets, triggered by the rise of the internet and of digital broadcasting, has generated more intense competition for audiences, while advertising revenues have not recovered from the financial crisis of 2008. As the fragmentation of the audiences has accelerated, commercial revenues have been on the decline, thereby increasing the role and market power of state advertising (by ministries, municipalities and state-owned companies).

3.3. Political Independence (85% ‒ high risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

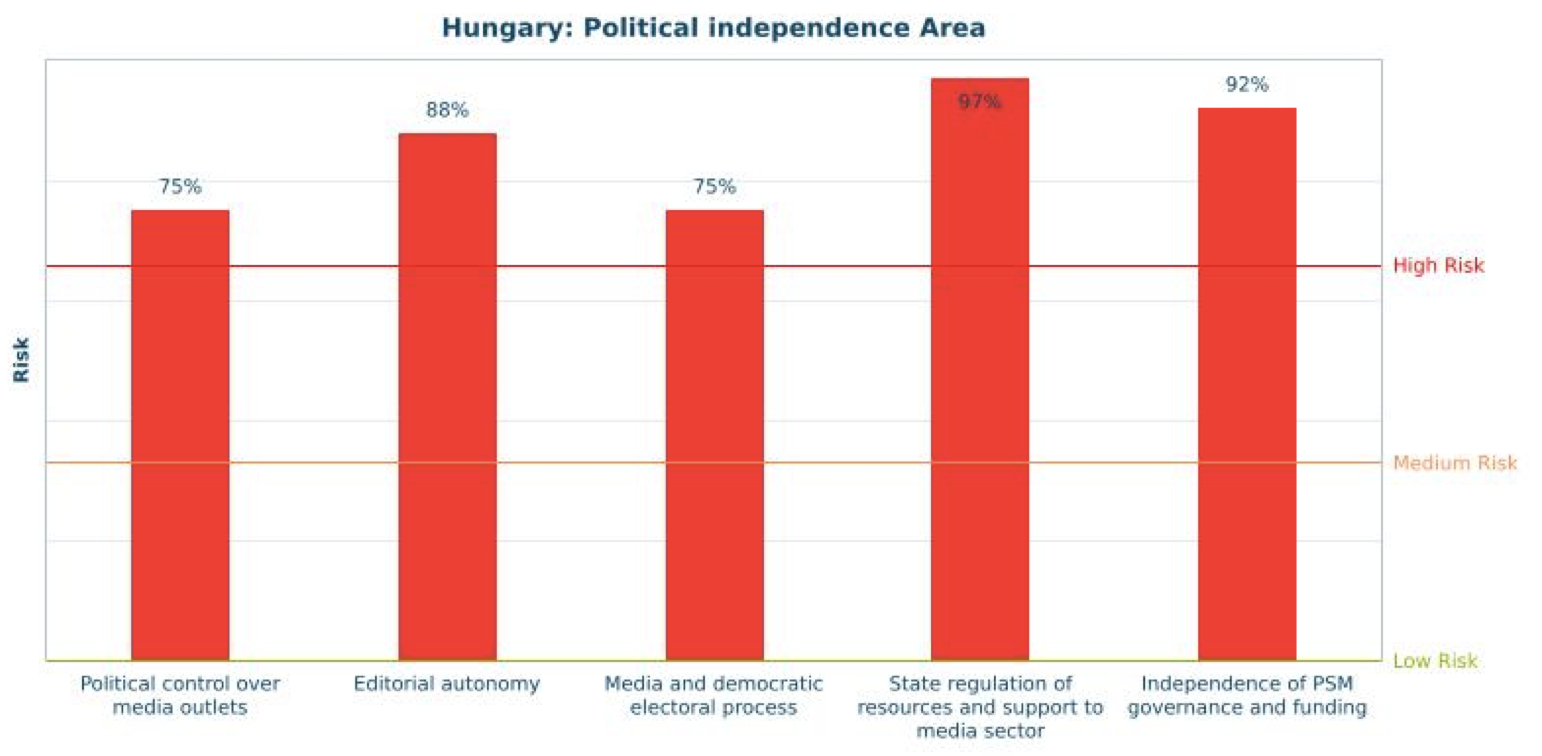

All indicators in the area of Political Independence score a high risk, with the highest one being the state regulation of resources and support to media sector.

Political control over media outlets scores a high risk (75%). The Media Act sets out conflict of interest provisions regarding who can provide linear media services, which includes provisions restricting political parties and politicians from providing these media services. However, politicians and political parties exert direct and indirect influence and control over media via proxies, straw men and oligarchs.[10] In practice, therefore, political control over media in Hungary is common. Political elites typically exert control over broadcasting through ownership and economic levers (taxation policies and advertising revenues). At present, the current Fidesz government has a dominant footing over the commercial TV and radio markets, primarily through a network of indirect ownership among a group of Fidesz-linked business moguls and oligarchs. As with the broadcast media, newspapers are also subject to a high level of political control, often through ownership ties as well as via state advertising revenues. As with the media market as a whole, the print market is highly polarized along political party lines. In more recent years, the print market has been undergoing extensive changes, due to steady declines in revenues, a series of mergers and acquisitions, and the launch of new outlets established by Fidesz-linked companies. Since 2010, government-linked business affiliates have acquired or launched new print titles, despite declining revenues across the print sector.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy is at high 88% of risk. Hungary’s media market in practice is highly polarized along political-party lines. TV and radio stations on the national, regional and local levels are typically aligned with either right or left politics and reflect these viewpoints.

Media and democratic electoral process indicator also scores a high risk (75%). The Media Act specifies that PSM channels and services should provide fair, balanced and impartial representation of political viewpoints in news and informative programmes.[11] In practice, since the public service media system was restructured in 2010, the public media content has been marked by a demonstrable pro-Government bias. According to monitoring data by the media regulator (NMHH), Fidesz MPs and government officials are granted a majority of airtime on PSM channels compared to other parties/party officials. An analysis of 2011-2013 data show that of the two public TV channels measured, (M1 and DUNA), the government, Fidesz, and its coalition partner KNDP officials were given 81% of speaking time compared to 15% for other parties combined (MSZP, LMP and Jobbik).[12]

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to media sector scores a highest risk in this area (97%), mainly due to the lack of fair rules and transparency on distribution of state advertising. There is no legislation regarding the distribution of direct or indirect state subsidies to private media. However, the state effectively subsidizes private media through advertising. In the last few years, the government, state-owned companies, institutions, and ministries have become important media advertisers in Hungary. The distribution of state advertising is based on political favouritism, benefiting media outlets allied or linked with the government and the ruling party Fidesz.[13] From 2010 to 2014 the main beneficiary of state advertising allocation was the so-called “Simicska media empire” owned by the country’s top oligarch and close friend of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Following the 2014 elections, the government established a new body for advertising budget allocation, the National Communication Bureau which holds a HUF 25 billion (EUR 80 million) budget for media buying annually.

Finally, the Independence of PSM and funding is also at high risk (92%). The 2010 media legislation brought extensive restructuring to Hungary’s PSM. Each of Hungary’s public service media outlets—three national TV, three radio stations and one national news service—are now supervised by a single body, the Media Services and Support Trust Fund (Médiaszolgáltatás-támogató és Vagyonkezelő Alap, MTVA), managed by the country’s media regulator, the Media Council, a body composed of five members who were all appointed and elected by the governing majority.[14]

The chairperson of the Media Council appoints, sets the salary for and exercises full employer’s rights over the MTVA’ s director general, deputy directors, as well as the chairperson and all four members of its Supervisory Board. The Media Council is responsible for approving the Fund’s annual plan and subsidy policy and for determining the rules governing how MTVA’s assets can be used, managed, and accessed by the public media. The Fund’s annual budget is approved by Parliament.

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (46% ‒ medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator Access to media for minorities scores low risk. The 2010 Media Act guarantees access to public media for various groups, including ethnic, religious, local and regional communities, as well as for people with disabilities. There have in recent years been a number of civic initiatives aimed at producing minority programming as well as at providing education for minority journalists. However, apart from the PSM’s weekly Romani programme, ‘Roma magazin,’ there is no other programme or television channel for Hungary’s largest ethnic minority.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities scores medium risk. Community media are awarded access to media platforms through tender procedures and decisions carried out by the Media Council. The 2010 Media Act specifies a range of programming provisions and obligations for linear community media.[15] According to these provisions, community media are “a) intended to serve or satisfy the special needs for information of and to provide access to cultural programmes for a certain social, national, cultural or religious community or group, or b) are intended to serve or satisfy the special needs for information of and to provide access to cultural programmes for residents of a given settlement, region or reception area, or c) in the majority of their transmission time such programmes are broadcasted which are aimed at achieving the objectives of public media services.”[16]

The indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk. The media law stipulates that audio-visual media service providers need to provide programmes accessible for the hearing impaired, stipulating that more programmes need to be provided with subtitles or in sign language every year. The PSM and the two leading national commercial television channels need to provide at least ten hours of programming per day with subtitles or sign language between 6-24 hours. Some programmes of the PSM and the leading commercial national television channels are subtitled.

Since new media laws were passed in 2010, the community media sector has undergone significant changes that have radically reduced the diversity of Hungary’s community media sector. Community radio licensing has been highly politicized since 2010, due to the National Media and Telecommunications Authority (NMHH’s) tendering practices which have generally favoured outlets that provide government-friendly, conservative and/or religious programming.

The indicator on Access to media for women scores medium risk. The Equal Rights Law 2003 guarantees women’s fundamental labour rights based on EU guidelines and frameworks. However, the issue of women’s equal representation in both the media and across all industries in Hungary is a persistent problem. There is no accessible data on the number or proportion of women journalists or in management positions in private media. As for the management of the Hungarian PSM (MTVA), seven of sixteen members of the management listed on MTVA’s homepage are women (as of October 2016).

The indicator on Media literacy scores medium risk. At present, media literacy is mainly addressed under the National Curriculum, the country’s new educational policy launched in 2013. The cited objective of media literacy is to “help students become responsible participants in a mediatized global public discourse and understand the language of both new and conventional media.” According to a 2015 study, efforts to centralize and homogenize media education along with the whole education may hamper the above stated objectives.[17] In addition, while the National Curriculum addresses digital literacy, poor IT infrastructures in schools combined with significant reductions in IT classes under the National Curriculum threatens to exacerbate the digital divide among low income students and social groups.

The 2010 Media Act also obliges the Media Council to promote media literacy.[18] The legislation specifies that it is the obligation of the PSM to “promote acquisition and development of knowledge and skills needed for media literacy through its programmes and through other activities outside the scope of media services.”[19] In 2014, the National Media and Infocommunications Authority launched a media and literacy education centre called the Magic Valley. The Authority has also hosted at least one major international conference, (Decoding Messages – Best Practices in Media Literacy Education), that involved input from range of international experts. In addition, it has published a book and education film package on media literacy that can be used in educational programs and schools. There is no data available on the impact or success of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority’s media literacy program.

4. Conclusions

The Hungarian media environment poses high risks to media pluralism. While there are formal legal mechanisms in place protecting freedom of expression, media pluralism is declining due to government influence over the market. This has been primarily achieved through legal/regulatory changes and market pressure, as well as through direct and indirect government interference with media outlets and journalists.

The private media sector is increasingly dominated by oligarchs with close government ties. In the past year, the right-wing media in Hungary has been reconfigured and expanded with new owners and outlets that actively promote the government line. The public service media was restructured following the passage of the media laws in 2010 and is heavily biased toward the government.[20] In its current state, the PSM in Hungary dramatically reduces media pluralism and the diversity of news available to the public.

Independent media exist, however these are mainly small online outlets and investigative reporting NGOs that are supported by crowd-sourced and international funds. Outlets supported by international funds have come under growing pressure from the government as attacks against civil society have intensified.

5. Recommendations

- To ensure inclusiveness and transparency, the Hungarian government should initiate public consultations before adopting any new laws related to the media market or that may impact media diversity.

- To mandate proportionate representation by all political parties as well as inclusion of professional groups and civil society organisations in the media regulation process, the government should revise the appointment procedures of the media regulator.

- To ensure that public media comply with the public service mandate, the government should introduce legislation that would lead to the decentralisation of the public media institutions.

- To improve transparency of media ownership, the government should create a public registry of beneficial ownership and introduce legal provisions that would require companies with such owners to register and disclose all ownership-related data.

- To improve transparency of state spend in the media, the government should make publicly available all the data related to how public funding is disbursed to media outlets.

- To ensure fairness and transparency of state spending in the media and reduce market distortions created by disproportionate allocation of state funds to certain media outlets, the government should introduce a mechanism that would mandate equitable spending of state advertising funds across media outlets in line with a set of principles and criteria for state ad spending.

Annexe 1. Country Team

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader |

| Amy | Brouillette | Researcher | CMDS | X |

| Attila | Bátorfy | Researcher | CMDS | |

| Éva | Bognár | Researcher | CMDS | |

| Dumitrita | Holdis | Researcher | CMDS | |

| Marius | Dragomir | Researcher | CMDS |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution

|

| Tamás | Tófalvy | Representative of a publisher organisation | Association of Hungarian Content Providers |

| Péter | Bajomi-Lázár | Academic/NGO researcher on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | Budapest Business School |

| Mihály | Gálik | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Corvinus University |

| Gábor | Polyák | Academic/NGO researcher on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | University of Pécs and Mérték Media Monitor |

| Ferenc | Hammer | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | ELTE University |

| András | Koltay | Media Council member | Media Council (NMHH) |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] 2011 population census. Data on nationality. Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Budapest 2014. https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/nepsz2011/nepsz_09_2011.pdf

[3] https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/xstadat_eves/i_qpt015.html

[4] Public opinion data from TARKI Social Research Institute https://www.tarki.hu/hu/news/2017/kitekint/20170130_valasztas.html

[5] https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2016/hungary-2016/

[6] Act CIV of 2010 on the Freedom of the Press and the Fundamental Rules of Media Content, (Smtv.), https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/152/Smtv_110803_EN_final.pdf

Act CLXXXV of 2010 on Media Services and Mass Media, (Mttv), https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf.

[7] §226 and §227 of the Act C of 2012 on the Criminal Code, (as amended 2013) in Hungarian at: https://net.jogtar.hu/jr/gen/hjegy_doc.cgi?docid=A1200100.TV. See English-language translation of the 1978 Criminal Code (§179 with almost identical language to 2012 Criminal Code) at: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/hu/hu019en.pdf

[8] § 9, Smtv, https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/152/Smtv_110803_EN_final.pdf

[9] ‘Council of Europe and Hungarian Government agree on changes to media laws’, The Hungarian Media Monitor, 6 March 2013, https://mediamonitor.ceu.hu/2013/03/1108/

[10] “Capturing Them Slowly: Soft Censorship and State Capture in Hungarian Media,” WAN-IFRA and CIMA, Center for International Media Assistance, and the Open Society Foundations, 2013; “Orban tightens grip on Hungary’s media,” Financial Times, Aug 2016.

[11] § 83 (1), Mttv. https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf .

[12] See NMHH content analysis of top TV channels: https://nmhh.hu/tart/polstat?lang=en&year=2014

[13] See, for example: Szeidl, A, and Szucs, F. (2016) Media Capture through Favor Exchange https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a942/2f02f6aa890261325948d05a190fa7ab4efa.pdf; Állami reklámköltés 2008-2012 (State advertising 2008-2012). Mertek, 2014. https://mertek.eu/sites/default/files/reports/allami_reklamkoltes.pdf and https://mertek.eu/2016/03/11/kereskedelmi-teve-allami-segitseggel/

[14] For example: https://mertek.hvg.hu/2015/08/14/a-mediaszabalyozas-leghatso-oldala/

[15] §66, Mttv. https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf

[16] §66, Mttv. https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf

[17] Anamaria Neag, “Media Literacy and the Hungarian National Core Curriculum – A Curate’s Egg,” Corvinus University, The National Association for Media Literacy Education’s Journal of Media Literacy Education7(1), 35 – 45.

[18] §132(k) Mttv. https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf

[19] §82(2)(c), Mttv. https://hunmedialaw.org/dokumentum/153/Mttv_110803_EN_final.pdf

[20] Szuroproba 10., Mertek Mediaelemzo Muhely 2017. https://mertek.eu/2017/01/31/szuroproba-10-kozmedia-hiradoinak-elemzese/