Download the report in .pdf

English – Greek

Authors: Anna Kandyla and Evangelia Psychogiopoulou

December, 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. Data collection in Greece was finalised on 31 July 2016.

In Greece, the CMPF partnered with the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP)[1], which conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Greek team organized a stakeholder meeting, on September 14, 2016 in Athens. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in Annexe 3.

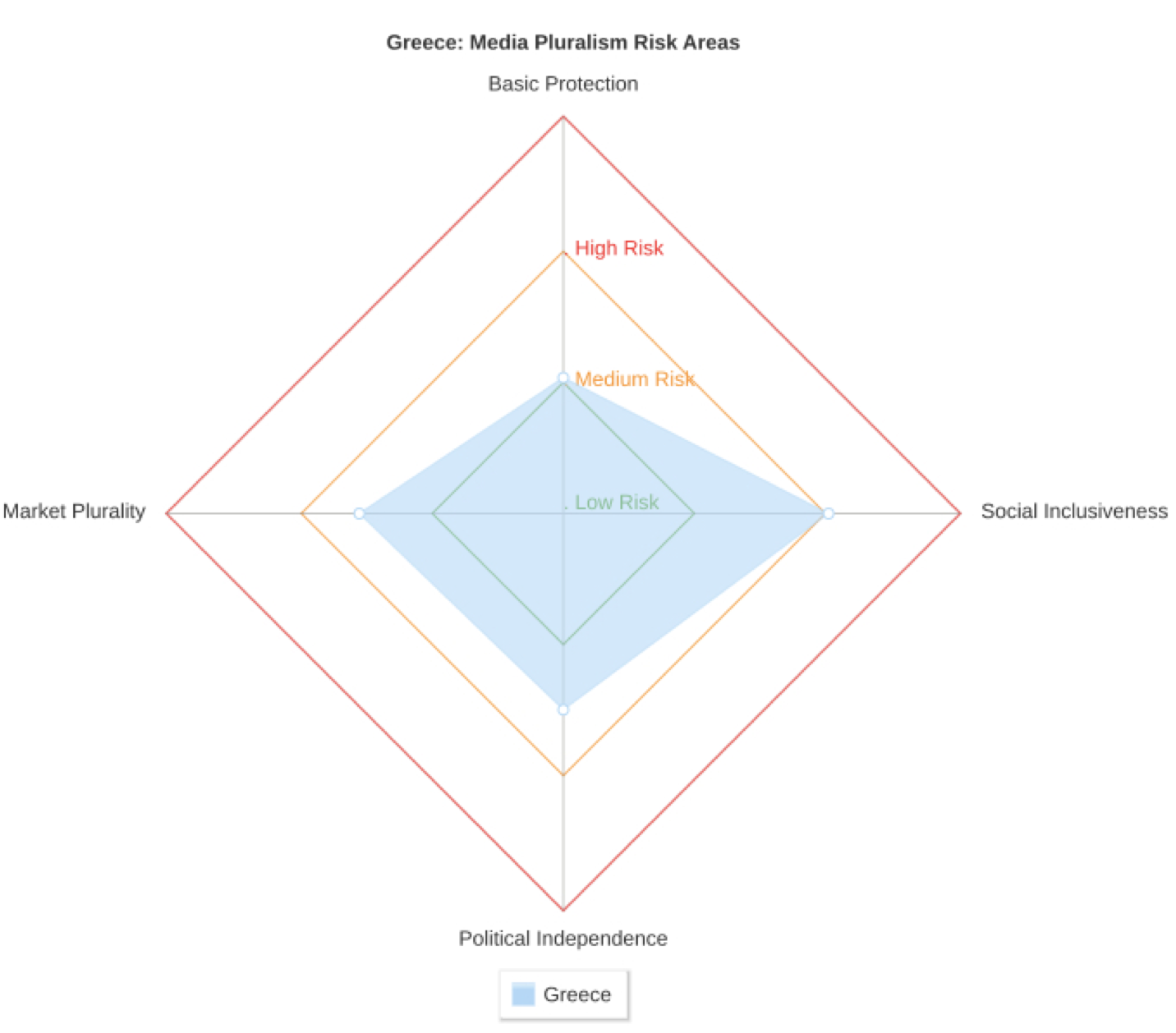

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of the right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[2].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Greece has a population of 10.82 million inhabitants. Greek is spoken by the overwhelming majority of the population. The Muslim minority of Western Thrace, with an estimated population of 100,000 persons, is the only minority that enjoys official recognition (UN, 2009). It consists of three main ethnic groups, each with its own language: Turkish, Pomakish and Roma. Other minority communities such as the non-Muslim Roma exist but their population is unknown due to the lack of official ethno-linguistically disaggregated census data. The number of foreign nationals residing in Greece is 822,000 (7.6% of the population) of which 623,200 are citizens of non-EU member countries (Eurostat, 2016).

Greece is undergoing a profound sovereign debt and financial crisis which has destroyed one quarter of its GDP (BBC, 2015). The crisis has affected both the public and private sectors of the economy, leading to a significant rise in unemployment. The economic hurdles of the country, its reliance on assistance from European and international rescue funds, and the relationship with its creditors have generated a crisis of political representation with repeated elections. The current governing coalition of the left-wing election victor Syriza and the national-conservative party Independent Greeks faces the adoption of further austerity measures and the handling of the acute refugee crisis.

Τhe media suffers reduced revenue from advertising and other sources due to the economic recession. This has resulted in layoffs, output reduction and media closures, engendering concern about the state of journalism and media independence (Iosifidis & Boucas, 2015). According to the November 2015 Eurobarometer survey, a large section of the population reports growing distrust in the media, especially in television (80%) (European Commission, 2015). Television is, nonetheless, the dominant market player. It attracted 50% of the media advertising expenditure in 2014, followed by magazines (23%), newspapers (20%) and radio (7%) (Media Services, 2016). Broadband coverage is almost ubiquitous and the number of internet users is on the rise, although it still lags behind the EU-28 average (Eurostat, 2014). Whereas single-copy newspaper sales figures are declining, a growing number of citizens cite the internet as their main source of political news (European Commission, 2015).

The reform of the media market has been a key issue in the agenda of the current government. One of the first actions taken was the reinstitution in June 2015 of the public service operator, Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ERT), which was abruptly shut down in 2013 on account of maladministration. As regards private audiovisual media, in October 2015 the government passed new legislation on the licensing of content providers of digital terrestrial television. It should be noted that existing television stations still operated with ‘temporary’ licences under legislative provisions that had been declared unconstitutional by the Council of State (i.e. the supreme administrative court in Greece). The new law foresaw that the relevant auction procedure would be carried out by the media regulatory authority (Ethniko Radiotileoptiko Symvoulio), ESR, which would also give its opinion to the Minister competent for the media on the number of licences to be granted. This presupposed reaching an intra-party decision on the replacement of those members of the authority’s board whose term of office had long expired. Following failure to reach such an agreement, the government adopted in February 2016 new laws which assigned the determination of the number of licences to the Parliament and the licensing procedure to the Minister responsible for the media. These laws spawned criticism for potential favouritism on the part of the government. The Council of State ruled in October 2016 that the sidelining of ESR is unconstitutional.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Τhe implementation of the MPM in Greece shows overall a medium risk for media pluralism. The lowest risk for media pluralism is identified in the area of Basic protection. The analysis indicates a higher risk, yet still within the medium risk threshold, for the domains of Market plurality”, and Political independence”. A high risk score emerges in the area of Social inclusiveness.

A high risk score is identified for some indicators. “Transparency of media ownership”, an indicator of the domain of Market plurality, is one of them. The score reflects primarily the lack of measures to ensure that the public knows who actually owns the media. As regards Political independence, “editorial autonomy” is at high risk due to the lack of formalized collective or individualized self-regulatory schemes at industry level. The indicator on the “independence of PSM governance and funding” is also flagged as a high risk. This is because the possibility of government interference with ERT’s operation through politically-motivated appointments to its board cannot be precluded. Regarding the Social inclusiveness area, the dominant ideology in the country about its ethnic and cultural homogeneity has led to resistance in acknowledging the existence of and granting rights to minorities. The high risk score for the indicator on “access to media for minorities” reflects this situation. The high risk identified for the indicator “access to media for local/regional communities and for community media” is also due to non-existent policies in this respect. Domestic media law further fails to make any specific provisions on community media, i.e. media that is non-profit and accountable to the community.

Overall, the analysis points to a situation that is not entirely satisfactory. In the sections that follow we elaborate on the scores obtained giving emphasis on the issue areas where there is room for improvement.

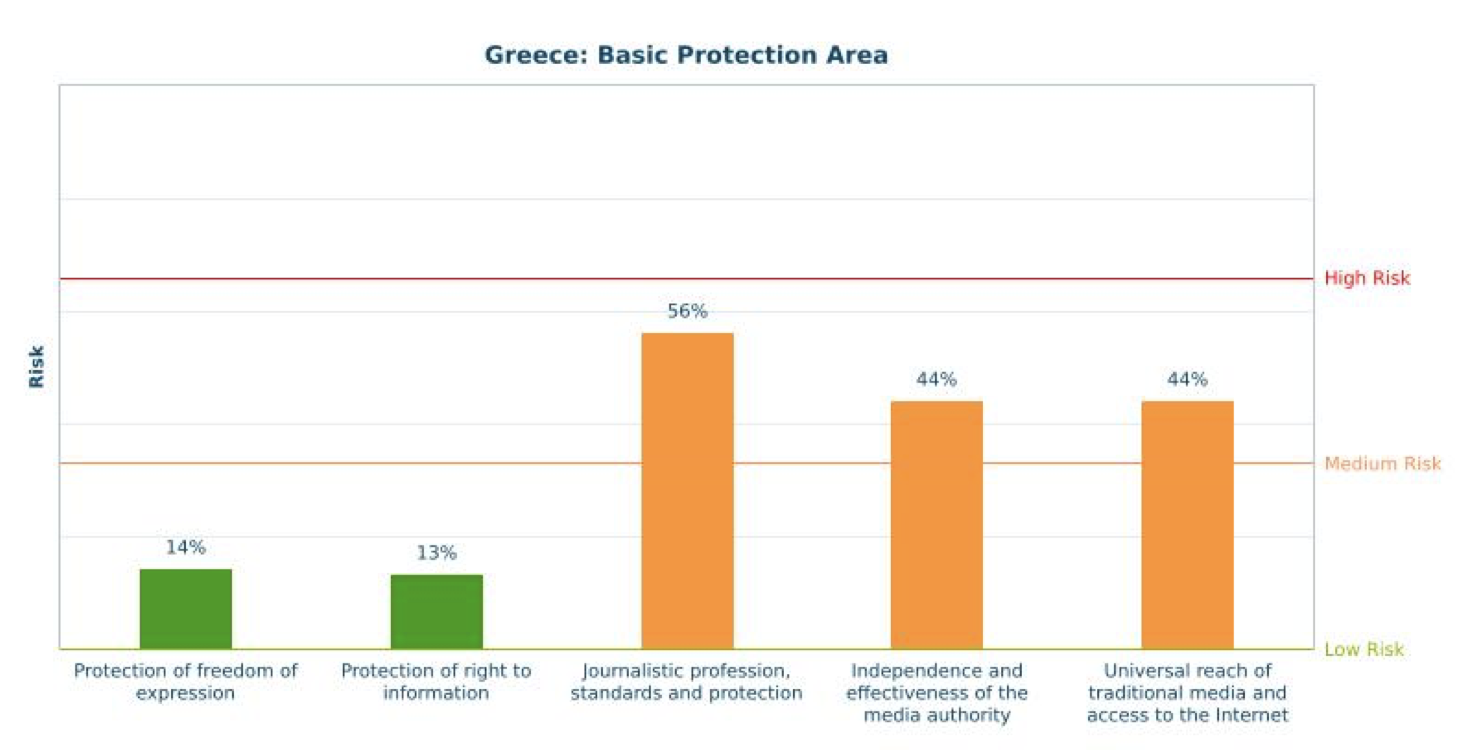

3.1. Basic Protection (34% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The risk to the Protection of freedom of expression in Greece is quite low (14%). Freedom of expression is explicitly recognised in the Constitution and the country has signed and ratified both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Citizens have legal remedies in cases of infringement of their freedom of expression and free speech is generally respected, including on the Internet. Although there have been interpretive problems regarding defamation provisions in the past, recent case-law suggests that the proportionality criterion is taken into account in line with Article 10(2) ECHR. However, the state has not decriminalised defamation. Moreover, rules on blasphemy exist and they are not narrowly defined.

The indicator on the Right to information scores a low risk (13%). The right to information is explicitly recognised in the Constitution and in national laws and there are appeal mechanisms in place if public authorities refuse to grant access to documents.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection is scored as medium risk (56%). In Greece, there is no licensing of journalists and access to the profession is open. Although the confidentiality of sources is not officially protected, the courts recognise that it constitutes an intrinsic part of free speech. However, journalists tend to operate under conditions which are far from satisfactory. First, the crisis has imposed flexibility on working conditions and job insecurity. It also appears to have contributed to threats and violence against journalists. Reporters, for instance, covering protests against austerity have at times been the victims of both riot police violence and violence by demonstrators accusing them of colluding with the government. Secondly, respect for professional standards is not effectively guaranteed. Journalists’ professional associations which are responsible for ensuring respect for editorial independence and professional standards through self-regulation are rather weak. Moreover, they cannot ensure the full commitment of media houses to relevant standards because their monitoring and sanctioning powers apply only to journalists who are their members.

The combined lack of budgetary autonomy and safeguards for independence give Greece a medium risk score (44%) for the indicator on the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority. The duties and powers of the media regulatory authority, ESR, are defined in detail in law. The authority enjoys quasi-regulatory and monitoring powers and can impose sanctions in case of violations. It is transparent about its activities. Its decisions – which constitute executable administrative acts – can be appealed before the Council of State. However, ESR is fully funded by the state and as such the possibility of political interference cannot be precluded. Its board members are selected by the Conference of Chairmen of the Parliament, a cross-party college, by an increased majority of four fifths of its members. Due to the ability of political parties to veto candidates, there have been considerable delays in the appointment of new members. For instance, at the time of data collection for the purposes of this report, the authority operated without a legally constituted board. Moreover, the nomination process lacks transparency and the qualifications for board membership are determined in general terms, which creates room for politically-driven appointments.

The indicator on Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet shows a medium risk (44%). Universal coverage of the PSM is guaranteed and broadband coverage is almost ubiquitous. Broadband penetration is low with only 56% of the population having a subscription. The average connection speed of 8mbps is also low compared to other European countries and there is a high ownership concentration in the ISPs market.

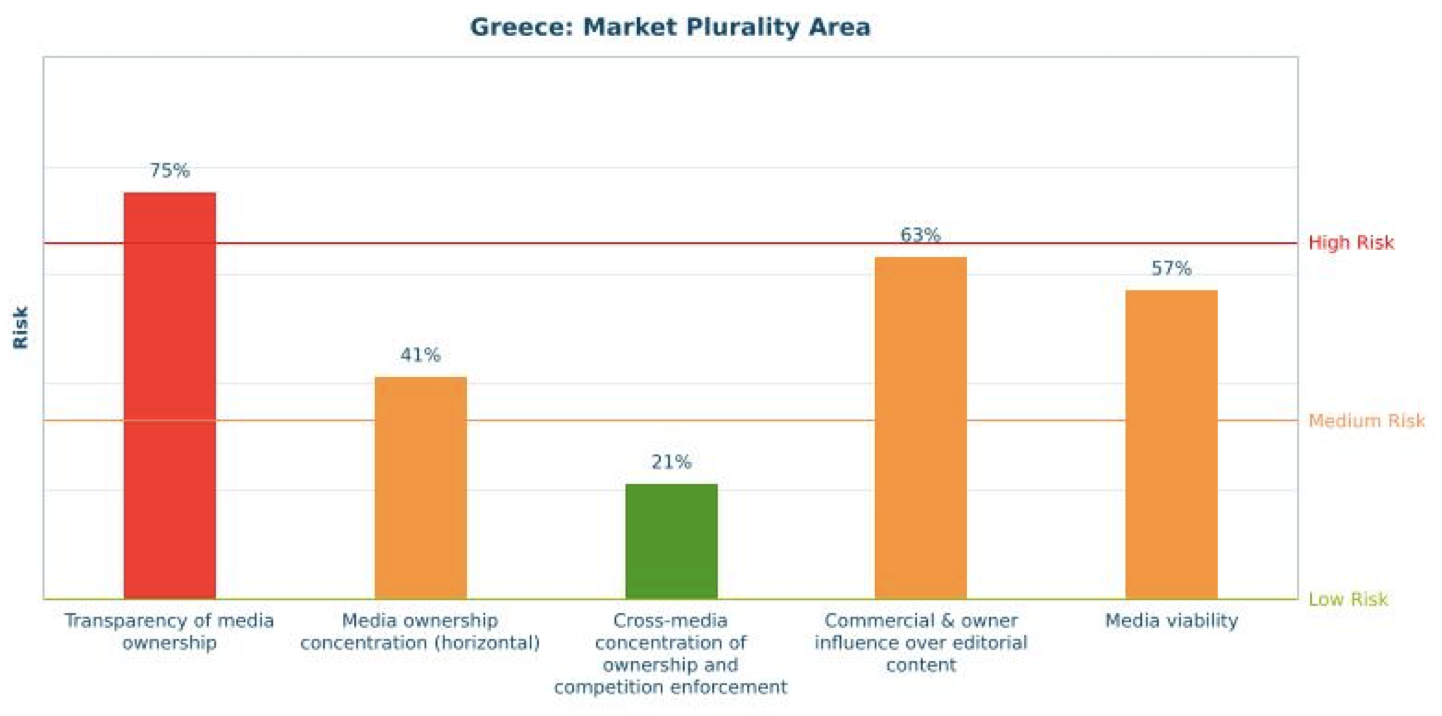

3.2. Market Plurality (51% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on Transparency of media ownership scores a high risk (75%). Broadcast media (TV and radio) are not required to make their ownership information accessible to the public. They are only mandated to report ownership structures and changes therein to the ESR. Sanctions apply in case of violations. However, the absence of agreements with foreign authorities, ESR’s limited ability to cross-check ownership information with other domestic bodies, and restrained capacity to scrutinize the information available due to insufficient resources undermine ESR’s monitoring activity. Disclosure obligations for the print media are limited to indicating the director and the publisher/owner on their copies without going to the level of final ownership.

The indicator on Concentration of media ownership (horizontal) shows a medium risk (41%). Media legislation (Laws 3592/2007 and 2328/1995) contains specific ownership limitations to prevent horizontal concentration in the broadcast media market. Compliance is checked by the ESR at the time of licensing and when changes in ownership structures occur. Yet, in practice the authority’s capacity to properly discharge its duty is hampered by the incoherence and incompleteness of the legal framework. Ownership limitations are further foreseen to prevent excessive horizontal concentration of ownership in the newspaper market (Law 2328/1995). However, no public authority is explicitly charged with supervising compliance with these restrictions. An important risk-increasing factor is the limited availability of data on ownership concentration in the broadcasting sector. Data on the market and audience shares of audiovisual service providers is not collected by public authorities and is not publicly available. The market share of the top 4 radio channels indicates a high level of horizontal concentration (67%) but no data on audience shares is available to complete the picture. As to the newspaper market, a medium level of ownership concentration is identified: the top 4 newspapers have a market share (measured by share of advertising expenditure in 2015) of 41% and a readership share of 25%.

The indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement shows a low risk (21%). This good score can be attributed to several factors. First, media legislation (Law 3592/2007) establishes specific thresholds to prevent excessive cross-media ownership concentration. Second, these provisions, along with general competition rules, apply in the case of mergers. Third, the monitoring of compliance with these rules is assigned to the Hellenic Competition Commission (HCC), which enjoys sanctioning powers and can impose proportionate remedies where the applicable thresholds are not respected. It can be argued, nonetheless, that the low risk calculated by the tool underestimates the situation. Specific ownership restrictions may well exist but their effectiveness is questionable. They have been, for instance, criticised for affording a much more lenient approach to cross-media ownership compared to general competition rules (see Tsevas, 2010). Furthermore, the evaluation of the actual cross-media concentration is not possible due to lack of data.

Regarding Commercial and owner influence, Greece scores at the upper end of the medium risk range (63%). The journalist’s self-regulatory code of conduct proclaims the obligation of journalists not to accept any compensation that may affect their objectivity and their duty to resist any interference by their employers or superiors. It also stipulates that journalists can be involved in advertising only for charitable purposes. Moreover, advertorials are prohibited by law. What increases the risk is the lack of mechanisms for granting protection to journalists in case of changes in ownership and the editorial line. Safeguards to ensure that decisions on appointments/dismissals of editors are not influenced by commercial interests are similarly non-existent. In addition, cases disclosing interference of commercial enterprises with news content have been recently reported. Notwithstanding, hard evidence about the exercise of influence over editorial content is difficult to find.

The indicator on Media viability scores a medium risk (57%). Whereas radio advertising expenditure increased over the past two years, newspaper advertising decreased by almost 22%. Data on TV and online advertising revenue is lacking. The number of individuals regularly using the internet increased over the past two years and this is also the case as regards access to the internet on the move. At the same time, media support schemes for overcoming market difficulties or facilitating market entry are not available. Mainstream media enterprises, for their part, have not developed sources of revenue other than traditional revenue streams. Yet, some co-operative newspapers and magazines have been founded, aspiring to promote independent journalism.

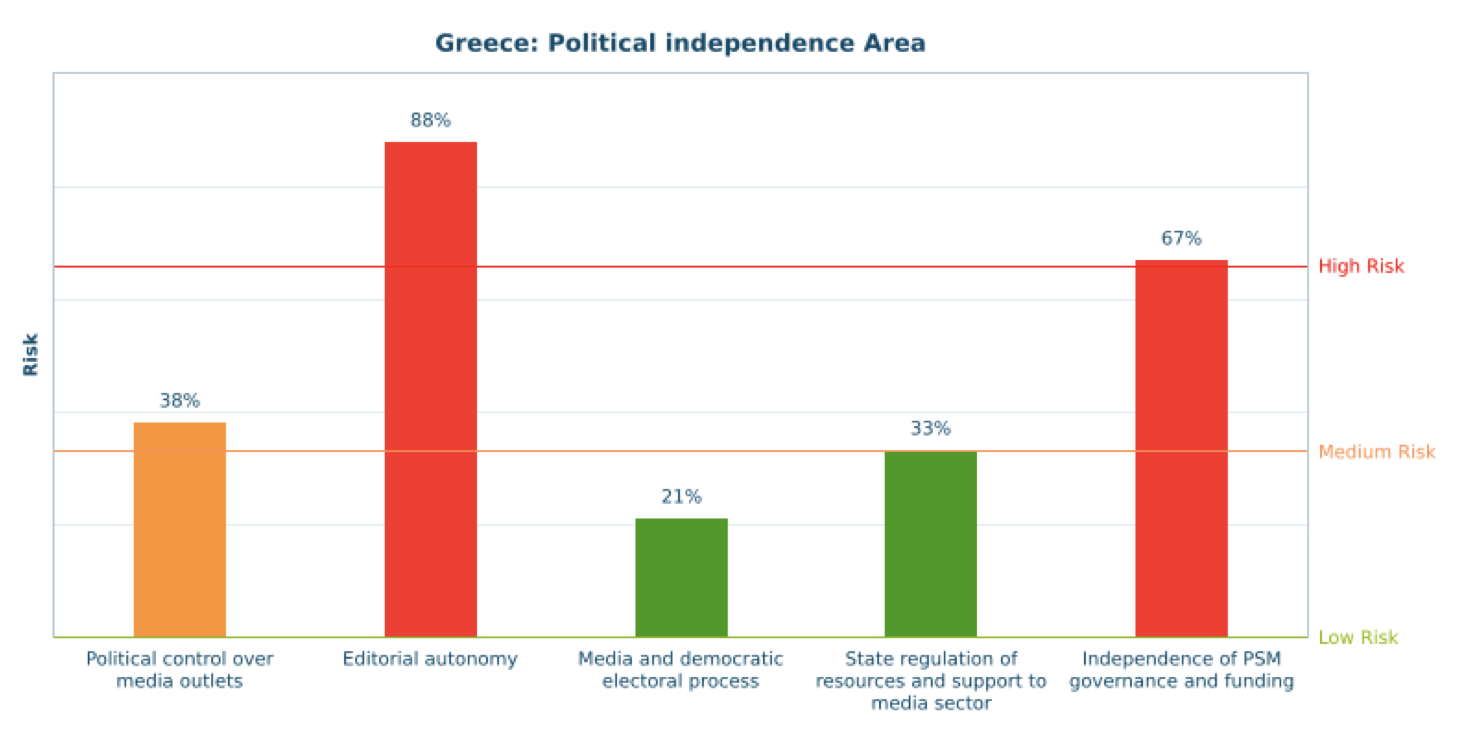

3.3. Political Independence (49% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The Political independence area scores a medium risk. A high risk is identified for the indicators on “editorial autonomy” and “independence of PSM governance and funding”.

The high risk score (88%) for the indicator on Editorial autonomy can be primarily attributed to the lack of protective mechanisms. Safeguards seeking to prevent political influence over the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief have not been established. Collective or individualised media industry self-regulatory schemes are similarly non-existent. The lack of a formalised and effective industry-level system protecting editorial independence, combined with the interconnections between the political elites and media owners (which the term “diaploki” has been coined to describe) create space for potential direct and indirect political influence on editorial activity. In practice, however, the extent to which such influence takes place cannot be assessed due to limited available evidence.

The indicator on the Independence of PSM governance and funding shows a high risk (67%). This score is not due to financial dependence. ERT enjoys financial autonomy (through a licence fee) and safeguards protecting the adequacy of its funding vis-à-vis the fulfilment of its remit exist. The worrying factor is that legislation does not guarantee the objective and transparent selection of the members of ERT’s management board. The involvement of the Parliamentary Committee on Institutions and Transparency in the selection procedure seeks in principle to guarantee democratic control and transparency. However, ERT’s board members are nominated by the Minister responsible for the media. Politically-motivated appointments cannot therefore be precluded.

The indicator Political control over the media outlets shows a medium risk (38%). The Constitution renders the duties of Member of Parliament incompatible with participation in/ownership of a TV, radio or country-wide circulation newspaper. It is not prohibited, on the other hand, for (ruling) political parties to own media. Currently, media outlets directly owned by political parties and Parliamentarians do not enjoy a leading position in the market. It should be noted, however, that the existence of indirect control (i.e. through intermediaries) of leading media enterprises by political parties and Parliamentarians cannot be assessed due to lack of data. Another risk-increasing factor is the lack of safeguards for ensuring the political independence of the country’s only news agency, ANA-MPA, in terms of governance. The members of ANA-MPA’s board are selected by the Minister responsible for the media.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector scores at the upper end of the low risk score (33%). As regards spectrum allocation, domestic legislation provides transparent rules and mandates respect for the principles of flexibility and efficiency and the promotion of competition to maximize consumer benefits. A key characteristic of the Greek media policy has, nonetheless, been the failure to allocate licences to broadcasters in the analogue era, a situation which persists in the digital terrestrial television market to date. The regulatory uncertainty in which content providers operate creates ample room for political interference. At the same time, in anticipation of positive coverage, content providers may be allowed to operate disregarding the rules. As regards state subsidies, the Greek media are supported by indirect subsidies in the form of reduced value added tax, postal distribution and reduced telecommunication rates. Whereas, however, rules for the fair distribution of these subsidies along objective criteria have been adopted, the process of their implementation lacks transparency. Problems of implementation exist also with respect to the distribution of state advertising to media outlets.

The lowest risk score under the area of Political independence concerns the indicator on the Media and the democratic political process (21%). This is attributed mainly to two factors. First, ERT is obliged to provide a fair representation of political viewpoints in news and current affairs programmes. Secondly, paid political advertising during all types of election campaigns and referendums is prohibited. Both ERT and private broadcasters are required to make time available for the transmission of political messages free of charge. The allocation of airtime to political parties is determined each time on the basis of the principle of proportional equality. ESR data indicate that this principle tends to be respected on ERT’s channels. This has not consistently been the case with private TV channels.

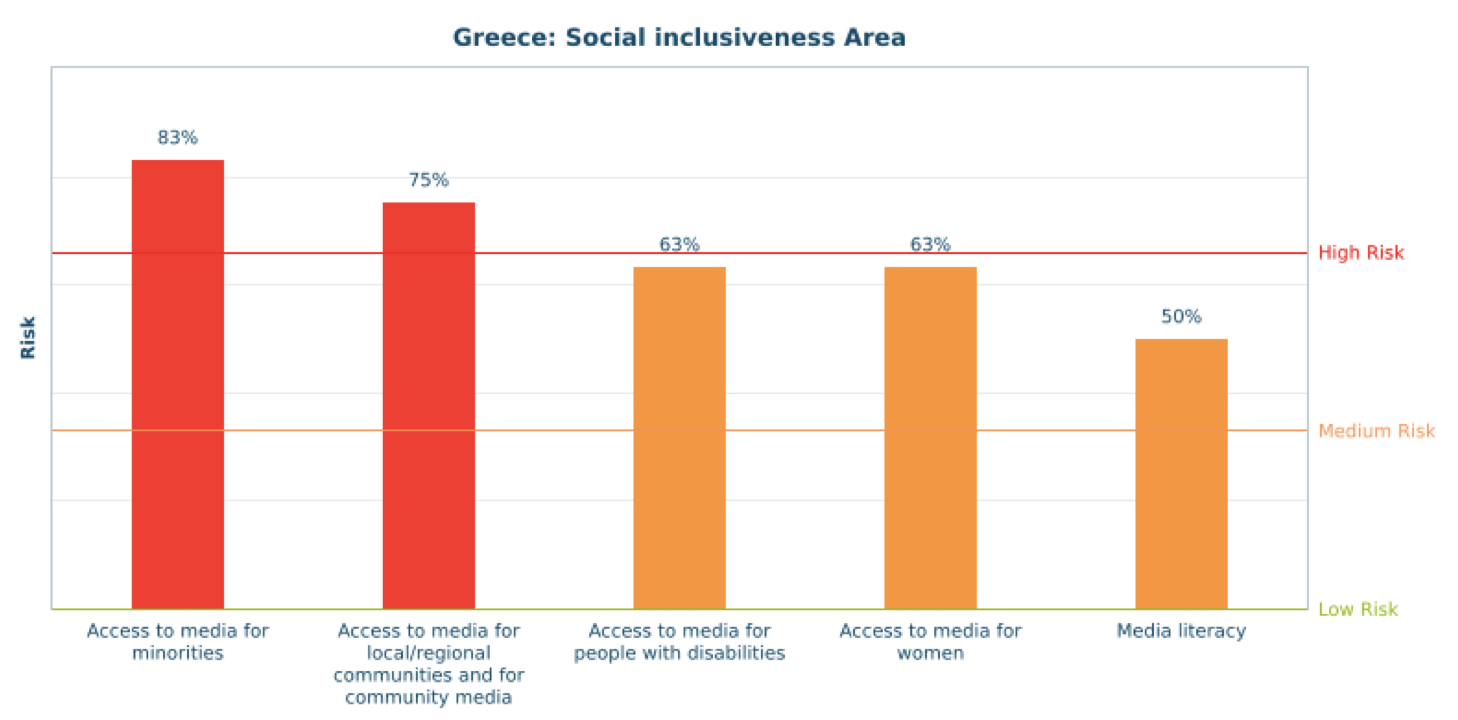

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (67% – high risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The analysis shows a high risk in the area of Social inclusiveness.

The indicator on Access to media for minorities shows a high risk (83%). First, ERT, the Greek PSM, is not obliged to broadcast content for minorities or content that is created by minorities. Private TV broadcasters are similarly not subject to any such requirements. An impediment to programming dedicated to minorities is the obligation for TV and radio channels to broadcast mainly in the Greek language. The law is silently not implemented for local radio in the region of Thrace: some radio channels broadcast solely or mainly in Turkish for the Turkish-speaking Muslim minority. Some local Turkish-language newspapers are also published in Thrace.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media also scores a high risk (75%). Domestic media legislation does not impose any must-carry obligations for regional or local TV or radio channels on network providers. Only a limited number of policy measures aim to support regional/local media. These include the rules concerning the allocation of public sector advertising and postal distribution subsidies which tend to favour local and regional media. ERT operates several regional radio stations for regional audiences but it is not mandated to have its own local/regional correspondents. No particular policy for community media exists.

Regarding Access to media for people with disabilities, Greece scores at the upper end of the medium risk range (63%). Domestic media legislation requires the PSM and private broadcasters to provide accessible content for people with hearing disabilities. This includes the provision of daily sign language bulletins subtitled in Greek and subtitled television content (e.g. current affairs, entertainment, etc.). However, the provision of subtitling is not universal. It applies to a limited part of broadcasting content. Moreover, requirements for audio description for the blind and partially sighted people do not exist.

The indicator on Access to media for women also shows a medium risk (63%). The principle of equality between men and women in employment is established in the Constitution and national legislation. It applies to employment relations governed by public and private law including in the media sector. As regards gender equality in PSM, ERT is generally committed to protecting equality in the selection of personnel but specific policies and monitoring mechanisms for the promotion of gender equality have not been adopted. At the same time, the representation of women in ERT’s management board is highly unequal.

The indicator on Media literacy scores medium risk (50%). Although there is no formal media literacy policy at state level, public authorities pursue various media literacy-related initiatives addressing citizens, and young people in particular. International cooperation on media literacy issues is also promoted. Media education is not autonomously studied. It is, nonetheless, integrated as a cross-curricular subject in several modules in both primary and secondary education. Several media literacy projects targeting students and educators further take place in non-formal educational settings. However, with respect to basic digital communication and digital usage skills, the percentage of Greek Internet users having such skills is below the EU average.[3]

4. Conclusions

The research carried out in Greece in the framework of the implementation of the MPM assessed risks to media pluralism based on a set of indicators. Overall, the results disclose a number of actual threats to media pluralism in the country. These require careful attention by policy-makers and relevant stakeholders. Our findings also reveal several potential threats to media pluralism. In such instances, policy measures are desirable to promote a pluralistic media environment.

First, there is a clear need to facilitate and strengthen media ownership scrutiny and transparency. In this context, it is important to ensure that the Greek public knows who effectively owns the media. Public disclosure of the ultimate owners of traditional and online media should, thus, be required. Moreover, public authorities should keep updated records of media ownership structures.

Secondly, mechanisms that protect and promote editorial independence from political and commercial influence as well as owner interference are needed. Part of the problem lies in the lack of media industry self-regulation. The establishment of voluntary collective self-regulatory schemes at the media industry level should therefore be encouraged. Consideration should also be given to measures aimed at ensuring that journalists’ self-regulation effectively protects the autonomy of journalists’ and editors-in-chief. Efforts to support editorial independence within individual media organisations should also be deployed.

Thirdly, given concerns over pluralism in the private media sector, the insulation of ERT’s management board from governmental influence is highly topical. Despite significant reforms brought about by the law that re-instituted ERT, the possibility of government interference with ERT’s operation through politically-motivated appointments to and dismissals from its board cannot be entirely precluded. Safeguards for open, transparent and de-politicized appointment procedures should, thus, be introduced.

Fourthly, domestic media policy is characterized by the absence of measures targeting community media and access to media for minorities. Concerning the former, it is vital to raise awareness of community media as a formal “third sector”. Explicit legal recognition of community media whose mission lies in their independent and participatory character should be made. Policy-makers should also give attention to the access of minority populations to media platforms and content. The influx of migrants and refugees into Greece renders the issue of cultural diversity through the media more salient.

Finally, our results indicate that improvements are desirable in a number of areas. Although, for instance, this might sound like wishful thinking in a period of profound economic crisis, consideration should be given to the adoption of measures that address the precarious state of journalism. It is also advisable to improve domestic legislation on the accessibility of the Greek media to the disabled in accordance with technological developments. Policy discussion concerning gender equality in the media should also start. Measures to encourage women’s access to, and representation in, PSM could be given consideration in this respect.

References

BBC (2015). The Greek debt crisis story in numbers. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33407742 [Accessed 1 August 2016].

European Commission (2015). Standard Eurobarometer 84, November 2015, Greece report. TNS OPINION & SOCIAL, Brussels. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/PublicOpinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/surveyKy/2098 [Accessed 1 August 2016].

Eurostat (2016). Migration and migrant population statistics . Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics#Migrant_population [Accessed 14 March 2017].Eurostat (2014). Survey on ICT (information and communication technology) usage in households and by individuals. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Internet_and_cloud_services_-_statistics_on_the_use_by_individuals#Internet_use_by_individuals [Accessed 1 August 2016].

Iosifidis, P. and Boucas, D. (2015). Media policy and independent journalism in Greece. Open Society Foundations. Available at: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/media-policy-independent-journalism-greece-20150511.pdf [Accessed 1 August 2016].

Media Services (2016). 2014 TV, radio and newspapers imputed advertising expenditure. Data provided upon request.

Tsevas, Athanasios (2010). Πολυφωνία και έλεγχος συγκέντρωσης στα μέσα ενημέρωσης [Pluralism and media concentration control]. Available at: https://www.constitutionalism.gr/1606-polyfwnia-kai-eleghos-sygkentrwsis-sta-mesa-enimer/. [Accessed 20 March 2016].

United Nations (2009). Reports submitted by States parties under article 9 of the Convention: International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination : 19th periodic reports of States parties due in 2007: Greece. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=publisher&docid=4aa7b7562&skip=0&publisher=CERD&querysi=greece&searchin=title&sort=date [Accessed 1 August 2016].

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Evangelia | Psychogiopoulou | Senior Research Fellow | ELIAMEP | X |

| Anna | Kandyla | Research Fellow | ELIAMEP | |

| George | Tzogopoulos | Research Fellow | ELIAMEP |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Dimitra | Dimitrakopoulou | Assistant Professor | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki |

| Petros | Iosifidis | Professor | City University London |

| Giannis | Kotsifos | Director | Journalists’ Union of Macedonia and Thrace Daily Newspapers |

| Alexandros | Oikonomou | Legal Officer | National Council for Radio and Television (ESR) |

| Katharine | Sarikakis | Professor | University of Vienna |

Note that the Group of Experts for Greece does not feature representatives of publishing and broadcasting organizations. The associations of publishers and broadcasters contacted for the purposes of this study did not respond to our invitation.

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

ELIAMEP held a closed event on 14 September 2016 to present the results of the implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) in Greece. The event, which took place at ELIAMEP’s premises in Athens, considered the main threats to media pluralism and media freedom in the country and served as a platform for debate for the challenges facing the Greek media policy in the context of the crisis and the online media.

The first part of the event was devoted to the MPM2016 project. It began with a description of the MPM by Dr Konstantina Bania, research assistant at CMPF, which set the scene for the presentations and the discussion that followed. Dr Bania provided some historical background to the development of the monitoring tool and explained the scope of the MPM2016, the areas of interest and the methodology. Then Anna Kandyla, research assistant at ELIAMEP, presented the results of the implementation of the MPM in Greece. Ms Kandyla elaborated on the areas identified as deficient in each of the domains evaluated by the tool and drew attention to the problems facing data collection and how they impacted the scores provided. The second part of the event featured presentations regarding the challenges and perspectives of media pluralism in Greece. Dr Alexandros Oikonomou, legal officer at the media regulatory authority, ESR, talked about the factors impacting the operation of the ESR as an independent and effective media regulator. Dr Markos Vogiatzoglou, advisor at the General Secretariat for Information and Communication, elaborated on the policy priorities and outcomes of the broadcasting content licensing tender that the government launched. He also presented future governmental initiatives as regards media pluralism and diversity.

The workshop brought together policy makers, journalists and academics. Overall, the reaction to the results of the implementation of the MPM was positive. Participants emphasized the importance of raising awareness about issues of media pluralism and the need for evidence-based research such as the MPM.

—

[1] The authors wish to thank the panel of experts and consulted institutions, professionals and academics for providing information.

[2] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[3] The share of Greek Internet user who has basic or advanced digital usage skills is 59% compared to a European median of 67%; and the share with basic or advanced digital communication skills is 61% compared to a European median of 77%.