This report presents the results and the methodology of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM2020), a tool geared at assessing the risks to media pluralism in EU member states and selected candidate countries (30 European countries in total). The Media Pluralism Monitor has been implemented, on a regular basis, by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, since 2013/2014 (last implementation MPM2017), based on a holistic perspective, taking into account legal, political and economic variables that are relevant to analysing the levels of plurality of media systems in a democratic society.

This implementation covers the years 2018 and 2019. Consequently, the United Kingdom – which left the Union in January 2020 – is still analysed as being part of the European Union in this report.

In a media ecosystem that has been rapidly evolving, especially under the pressure of the digitalisation of the information industry, rapid technological advancements have created new opportunities, but also new sources of risk for media pluralism. For this latest implementation, the Media Pluralism Monitor was revised and developed in order to insert, into its existing body, the analysis of the major features of the digital transformation, without renouncing the general character of the instrument.

This means that the analysis of the 4 areas of the MPM (Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness) has been integrated with several new variables that are related to the digital transformation, in the hope of obtaining a balanced and updated view of the reality of the present media systems in the EU and in selected candidate states. Furthermore, a special focus on the assessment of the digital variables has allowed the design of a preliminary evaluation of their specific contribution to the measurement of risks to media pluralism, and to extract a digital specific risk score, with the intention of advancing the agenda for public discussions and policy making in the EU (and beyond) about the effects of the digital transformation on our democratic societies.

Basic Protection

Under the Basic Protection area, the MPM assesses the fundamental factors which must be in place in a pluralistic and democratic society, namely, the existence and effectiveness of regulatory mechanisms in order to safeguard the freedom of expression and the right to seek, receive and impart information; the status of journalists in each country; the independence and effectiveness of the media authority; the universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet. This year, the Basic Protection area adds indicators focused on the challenges posed by the digital environment to the plurality of the media landscape; this results in a closer focus on the protection of freedom of expression online, data protection online, the safety of journalists online, levels of Internet connectivity, and the implementation of European net neutrality obligations.

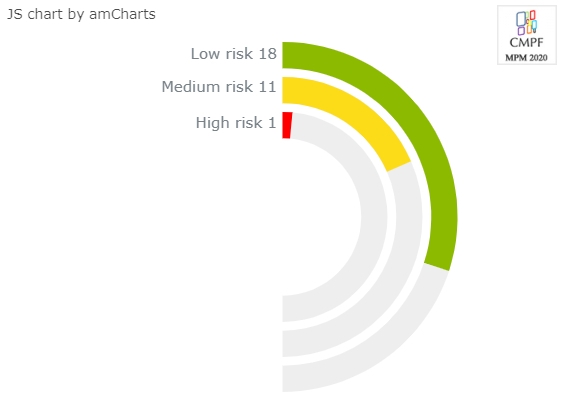

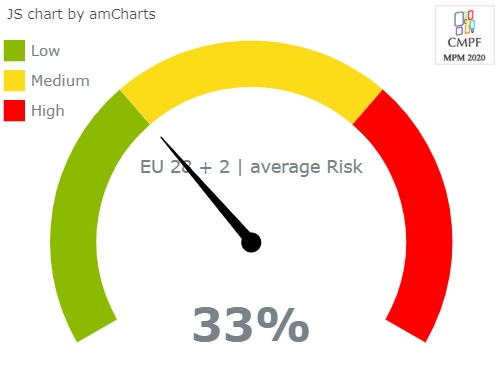

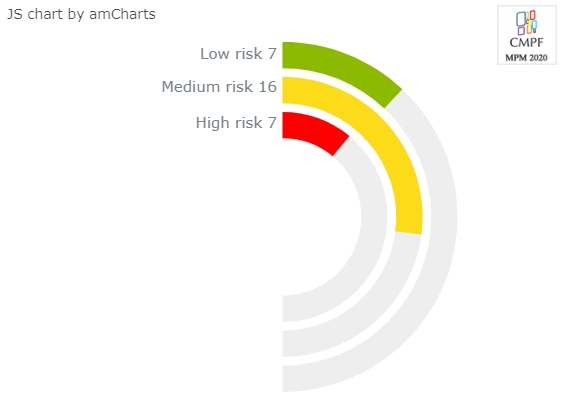

In the MPM2020, the majority of countries analysed score a low risk when it comes to the Basic Protection area: 18 of 30 countries are assessed as having a low risk (namely, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Sweden and the United Kingdom). 11 countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Spain) score medium risk, (with 1 country moving from low to medium risk (Cyprus) and 3 countries from medium risk to low risk (Greece, Latvia, Portugal) – which could be seen as a progress at first sight if compared to MPM2017, where 16 of 31 countries were assessed as being at low risk. However, the average score for the area of Basic protection, in this round of the MPM, reached 33%, a percentage very close to the medium risk range, an increase of an average 1% in comparison to MPM2017 – (when the average was 32%, still within the low risk range, although in its upper band). The assessment on Basic Protection shows a deteriorating situation in comparison with MPM2017 because MPM2020 assesses at higher risk the indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection: Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Italy, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain and the United Kingdom score as being at medium risk and Turkey as high risk for this indicator (in MPM2017, 6 country scored at medium risk and Turkey at high). In comparison with MPM2017, the indicator on Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet got a lower score. This impacts on the calculation of the average per area.

Only two indicators out of the five that compose the Basic Area assessment, i.e. Protection of freedom of expression and Independence and effectiveness of the media authority, score a low risk, on average. This does not mean, nonetheless, that the countries assessed under these two indicators are free from risks. In particular, within the indicator on Protection of freedom of expression, the assessment of the legal framework on defamation, and its implementation, shows the arbitrary use of lawsuits (the so-called Strategic lawsuit against public participation, or SLAPP), resulting in a chilling effect on journalists and limitations to the freedom of expression. A specific focus on protection of freedom of expression online shows that the main source of risk detected by the MPM2020 is the lack of transparency among online platforms in justifying and reporting on their content moderation policies and techniques.

The de facto independence of the media authority registers a medium risk in more than a half of the 30 countries considered. The insufficient protection of whistle-blowers, poor working conditions for journalists, and the increasing number of threats to which journalists are subjected, are some of the main risks that are observed across Europe. It is worrisome that threats to journalists often come from politicians, who should, instead, guarantee an enabling environment for journalists.

After the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta in 2017, the assassinations of Jan Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová in Slovakia, of Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and of Jamal Khashoggi in the consulate of Saudi Arabia in Istanbul. These all, sadly, confirm that Europe and the candidate countries are not immune from horrendous crimes against journalists.

Threats to journalists come from the online environment too. Digital safety has become a serious concern for journalists, including, in some countries: harassment and threats, especially against female journalists; legal provisions allowing national security services to collect internet and telephone data from citizens in bulk as a result of purposes of investigation and surveillance.

As in previous rounds of the MPM implementation, Turkey is the only country that scores a high risk in Basic Protection, confirming a trend to deterioration in the protection of fundamental rights and values. Of particular concern, is the still high number of imprisoned journalists in the country (47 as of December, 2019), coupled with a lack of independence among the judiciary and abusive use of the criminal justice system, in particular, when it comes to limiting freedom of expression. The trend to the prosecution of writers, journalists and social media users for insulting the President has grown. Journalists have been prosecuted and imprisoned on extensive charges of terrorism, insulting public officials, and/or committing crimes against the state. Turkey, again, is the only country scoring high risk when it comes to protection of freedom of expression online: administrative authorities and courts routinely have recourse to internet blocking in a way that is disproportionate and that is not compatible with Art. 10 ECHR (just on December 26, 2019, the Constitutional Court of Turkey ruled that the blocking of Wikipedia, ordered in 2017, violated human rights).

Market Plurality

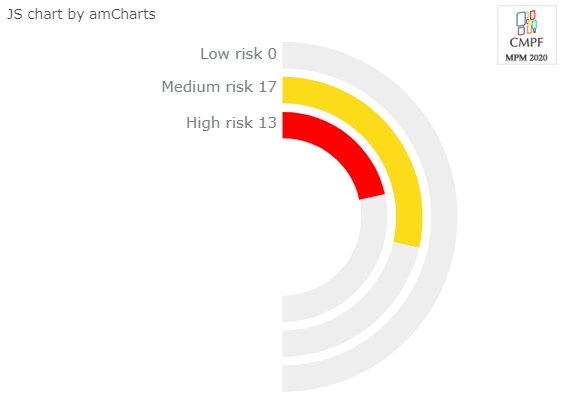

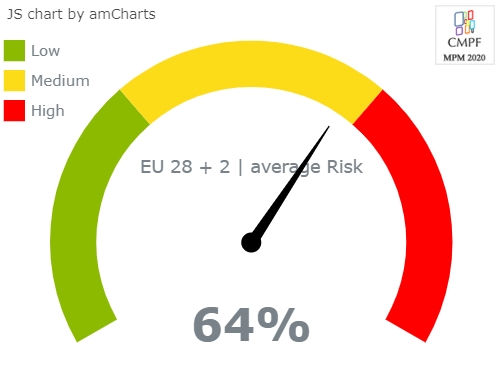

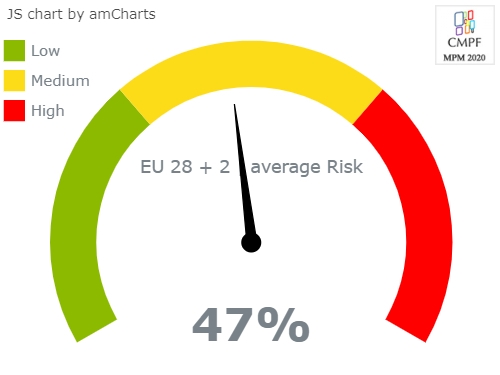

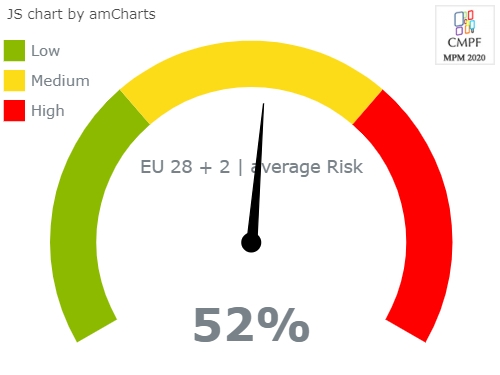

Under the Market Plurality area, the MPM assesses the risks to media pluralism that arise from the legal and economic context in which market players operate: market concentration, transparency of ownership, businesses’ influence over editorial content, the sustainability of media production. In the MPM2020 implementation, the role of the digital platforms in the new ecosystem of the media has been considered, assessing separately the concentration in the production and distribution of information. While the indicator on News media concentration assesses the risks of market power in the production of news (both legacy and digital providers), a new indicator (Online platforms and competition enforcement) addresses the role of the digital intermediaries in the distribution of news. The average score for the area of Market Plurality is 64%, which is considerably higher than in MPM2017 (53%), signalling the growing economic threats to media pluralism.

Under Market Plurality, no country scores a low risk; and this area has the highest average risk among the areas considered by the Monitor. The majority of countries score a medium risk – 17 out of 30 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom), while 13 countries score a high risk (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Turkey).

The highest risks for market plurality come from ownership concentration, both in the news media and the digital intermediaries’ markets. The indicator on News media concentration scores 80%: for this indicator, no country scores a low risk, and only four countries (France, Germany, Greece and Turkey) score a medium risk. The new indicator on Online platforms and competition enforcement is also at high risk (73%), reflecting the very high concentration in Gateways to news (80%), and a medium risk in Competition enforcement (65%, very close to the threshold of high risk).

The role of digital intermediaries indirectly affects the indicator on Media viability: it ranks a medium risk, at 56%, reflecting the tough market in which the news media industry is struggling. By collecting users’ personal data and using them for targeted advertising, the online platforms take the major share of the online advertising market, thus disrupting the traditional business model of the news media. In seven countries, Media viability is assessed as being at high risk. Among the news media sectors, the most vulnerable are newspapers and local media industries.

The other two indicators in this area are at medium risk: Transparency of media ownership (52%) and Commercial and owner influence over editorial content (60%). Only four countries score a low risk level for the indicator on Transparency of media ownership (France, Germany, Luxembourg and Portugal); while five countries score a high risk (Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia and Slovakia).

The risks relating to commercial and owners’ influence over editorial content have risen from MPM2017. In the MPM2020 implementation, only 5 countries score as low risk (Denmark, France, Germany, Portugal and the Netherlands). 11 countries score as medium risk (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain, and the United Kingdom), the remaining 14 being at high risk (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and Turkey).

Even if the impact of digital competition affects all of the indicators in the area, the extraction of the score for digital variables can help to better assess the risks that are linked to the online environment. The average score of the digital variables for the Market Plurality area is 61%, (i.e. medium risk). It is slightly lower in comparison with the overall risk (64% for EU+2, 63% for the EU).

In each of the five indicators of the Market Plurality area, the digital score is at the same risk-level as the overall score, but with different numerical values. In the indicators on market concentration, the digital variables mark a very high level of risk: 80% for News media concentration, 77% for Online platforms and competition enforcement. The sub-indicator on Gateways to news (which aims to assess the role of algorithm-driven access to news, and the concentration in the online advertising market) scores as a high risk in all the countries monitored by MPM2020.

The data collection in the Market Plurality area has been challenging, particularly for the digital variables. Based on the MPM methodology, lack of data is coded as “no data” in the MPM questionnaire and the consequent level of risk is assessed having regard to the country context. “No data” coding in the Market Plurality area amounts to 18% of all the questions in the area itself (compared to 7% for all of the MPM’s areas), highlighting a high degree of opacity that, in itself, can be seen as a risk for market pluralism.

Political Independence

Political pluralism, as a potential for actively representing the diversity of the political spectrum and of ideological views in the media and other relevant platforms, is one of the crucial conditions for democracy and democratic citizenship. The Political Independence area is assessed using indicators that evaluate the extent of the politicisation of the distribution of the resources to the media; political control of media organisations and content; and, especially, of the public service media. The area evaluates the editorial autonomy to self-regulate in traditional and digital news environments, and safeguards against manipulative practices in political advertising in the audiovisual media and on online platforms. Media policies and media regulation have mainly been focused on audiovisual media, because of their perceived impact on public opinion, and because of their use of finite spectrum resources. As more people are shifting their attention and news habits to online platforms and sources, more attention needs to be given to the conditions in which political information there is shared, moderated and accessed. The MPM2020 thus introduces a set of variables that aim to assess the political control over digital native media, the fairness and transparency of (micro-targeted) political advertising on the social media, and the potential for journalists to self-regulate their activities in the platform’s realm.

Overall, the Political Independence area is at high risk in 7 countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Turkey). Seven other countries are found to be at low risk (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden). A majority of countries, namely, 16, including a candidate country, Albania, in which the MPM was implemented for the first time in 2018-2019, score medium risk.

While, on average, for all of the countries covered by the research, the risk remained almost the same as in MPM2017 (when it was 46%), in several cases the level of risk has changed. Malta and Romania, which, in MPM2017, performed within the medium risk band, but were scored as being very close to high, now score a high risk. In both cases, this is largely due to the increase in risk for the indicator Audiovisual media, online platforms and elections. Unlike the MPM2017, when this indicator was purely focused on audiovisual media in elections, in the MPM2020 it was redesigned to also evaluate the conditions and safeguards for fair play and the transparency of political advertising online, including those online platforms that distribute content. While most countries in the EU have a law or another instrument with which to ensure transparency and allow equal opportunities in political advertising during election campaigns in the audiovisual media, this is far from being a reality in the online sphere, where different possibilities are offered, and different techniques are used to influence political opinions.

Turkey continues to be the only country that scores high risks across all five indicators in the area of Political Independence. Overall, for all of the 30 countries examined, most risks in the area of Political Independence relate to the lack of regulatory, or self-regulatory, protection of editorial autonomy. The risks are further associated with the general lack of political independence of the media: conflicts of interest between holding government office and media ownership, especially at the local level, is often not effectively regulated, and other indirect means of political control over the media, such as state advertising, are also used. Public service media, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, are at the risk of government interference through the appointment of politically dependent management.

Social Inclusiveness

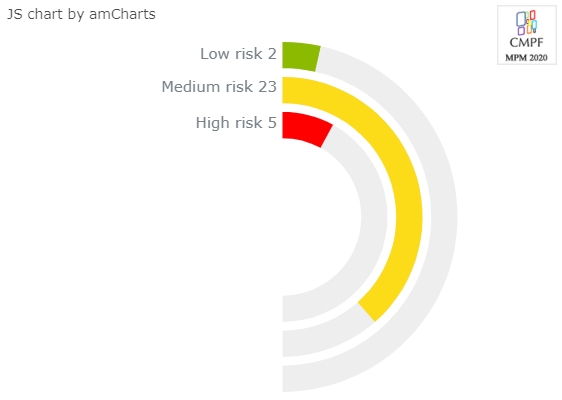

The Social Inclusiveness area considers access to the media by various social and cultural groups, such as minorities, local/regional communities, people with disabilities, and women. In addition, the Monitor considers media literacy as a precondition for using the media effectively, and examines media literacy contexts, as well as the digital skills of the population. On average, the area of Social Inclusiveness scores 52% (i.e. medium) risk. This is 2 percentage points lower than in MPM2017 (54%), but is still in a medium risk band. Two thirds of the countries (22) score a medium risk (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain), 5 countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Romania and Turkey) score a high risk, while only 3 countries (France, Sweden and the United Kingdom) are in the low risk band for Social Inclusiveness.

Access to media for minorities, and Access to media for women, are the two highest scoring indicators in this area. The risk is particularly prevalent with regard to minorities who are not recognised by law. Women continue to be heavily underrepresented in both media management and reporting. Male experts are more often invited to comment on political programmes and articles than are female experts, and no country scored a low risk on this matter.

While media literacy activities are gaining popularity in both the number and scope in the majority of the countries examined, media literacy policies are evaluated as being comprehensive in only 6 (Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden). In the vast majority of countries, namely, 19, media literacy policies are available, but they are not comprehensive, and 5 countries have no media literacy policy at all (Albania, Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, and Romania). The lack of systematic and state-level effort to increase media literacy may be reflected in the overall digital competencies of individuals. It is largely those countries that do have a comprehensive media literacy policy that also have a higher share of the population with basic, or above basic, overall digital skills, as compared to those that have no, or only a limited policy in this field.

The novelty of the MPM2020 Social Inclusiveness area is a new component of the Media literacy indicator: Protection against hate speech. The MPM2020 results show that 4 countries only (Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, and Sweden) have regulatory frameworks that appear to be effective in countering hate speech online, especially with regard to vulnerable social groups, such as minorities, people with disabilities and women. In many countries, there is still insufficient research into the extent and form of hate speech against these and other groups or individuals in the online sphere, but indications are that such hate speech is taking place and represents a severe problem.

As mentioned above, MPM2020 devotes a special focus to the evaluation of the specific risks to media pluralism in the digital environment.

Media Pluralism in a digital environment

With the exception of the Market Plurality area, the risk scores of the digital component of each area are, in general and on average, higher than the overall score in that area.

The average score of the “digital” variables in the Basic Protection Area results in a medium risk, slightly higher than the general low risk average for the same area. While the assessment on the digital dimension of Basic Protection is somehow comparable to the overall score for this domain, it presents some specific elements that generate additional risks, such as online surveillance and digital threats to journalists, access to the internet, and availability of broadband connection that is below the EU’s median in half of the analysed countries, together with the ineffective implementation of net neutrality.

In the Market Plurality Area, the risk score for the digital market is slightly lower than the overall risk. Transparency of media ownership and businesses’ influence over editorial content perform relatively better, even if they are still, on average, at medium risk; this may be due to the very features of digital native news media businesses, as well as to the progressive inclusion of digital media in the regulatory and self-regulatory provisions; but a growing concern relates to ownership transparency for cross-border digital news media. However, the digital score for the indicators on market concentration is equal to, or higher than, the overall score. Even if it has low entrance and production costs, the sector for online news media turns out to be at high risk in horizontal concentration. Also the specific indicator aimed to measure the impact of online platforms on media market pluralism shows the overwhelming dominance of a few digital intermediaries; consequently, the online advertising market is highly concentrated (in most countries the first two players controlling around ⅔ of the market). Finally, the digital score for Media viability is lower than the overall score, reflecting the fact that, in terms of revenues and employment, the legacy media suffer more, while, in the digital field, the development of alternative business models is continuing.

In the Political Independence Area, the higher risks are largely associated with the lack of proper safeguards, monitoring, and the transparency of political advertising on online platforms, which are increasingly serving as a source of political information, and tend to give more prominence to paid content. On the positive side, the digital native media show significantly lower levels of politicisation than traditional media do.

As regards the Social Inclusiveness Area, the digital-specific risk score derives mainly from the under-investigated and inadequately handled issue of hate speech against vulnerable social groups online.

Pending the publication of this report, an unprecedented global crisis, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, has highlighted and confirmed the key role of independent media systems in democratic societies, and the risks to media pluralism associated with a state of emergency and various restrictions on freedom of expression. This crisis has boosted an “infodemic”, parallel to the health emergency itself, leading to a rapid spread of disinformation, sometimes boosted by politicians themselves. This situation has placed the big platforms in the spotlight even more, as they have found in a position to contribute to the diffusion of disinformation and, conversely, a public demand to act to fight it.

The crisis has demonstrated how “quality” journalism, based on the standards of professional ethics, is fundamental to keeping the public informed. The crisis has also forced media companies to think of alternative business models as news consumption habits change. The emergency has also highlighted how strategic and essential access to the Internet and digital media literacy have become in contemporary democracies.