Authors:

Wolfgang Schulz, Hermann-Dieter Schroeder, Kevin Dankert (Hans Bredow Institut)

October 2015

1. Introduction

The most widely accessed media channels in Germany are television and radio. 84% of the population watch television every day via a conventional TV set, while 5% consume programming via Internet platforms. 69% listen to radio on a daily basis. Digital satellite and cable make up the preferred modes of transmission for television content, while terrestrial, analogue services prevail for radio. The Internet is used daily by 57% of the population, and print media is consumed every day by 56%.

The media system in Germany is determined by the constitution and the settled case law of the Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht). Media affairs are regarded as being a cultural matter that falls under the legislation of the sixteen federal states (Bundesländer). Regulation of the mass-media is, however, in part, unified by interstate treaties.

Most regulatory measures, as far as the media are concerned, focus on television, due to the perception that it is highly influential in forming public opinion. The Federal Constitutional Court and the basic law guarantee that public service broadcasting is not state controlled, and that policies exist to enhance media plurality and to limit media concentration.

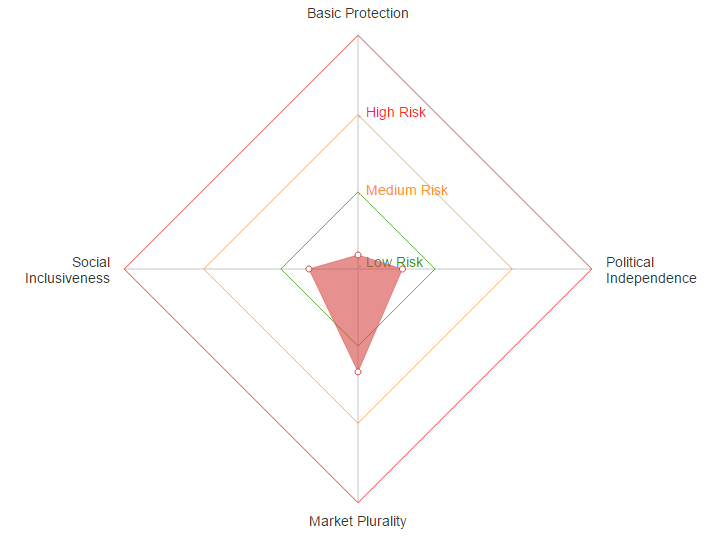

Implementation of the MPM2015 indicates, in general, a low to medium risk to media pluralism in Germany.

2. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

2.1 Basic Protection (6% risk – low risk)

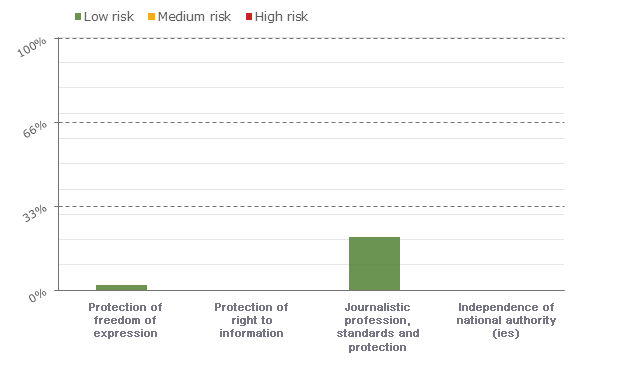

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy and they measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; as well as the independence and effectiveness of national regulatory bodies, namely media authorities, competition authorities and communications authorities.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Protection of freedom of expression | 2% risk (low) |

| Protection of right to information | Negligible |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | 21% risk (low) |

| Independence of national authority(ies) | Negligible |

For the ‘Basic Protection’ domain all of the indicators show very few risks to media pluralism in Germany. Freedom of expression (indicator: 2% of risk) is guaranteed by the German Constitution and by the ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and, to date, there is no evidence of any violations. Citizens have the right to a legal remedy in cases of infringements upon their freedom of expression. On the other hand, defamation is a criminal offence, thus posing some risks to the freedom of expression. Furthermore, freedom of information (negligible risk in the connected indicator) is protected by the constitution, by national law, and by appeal mechanisms against denials of freedom of information requests.

Risks to the standards of ‘Journalism, and to its protection as a profession‘, are low (21%). There is relatively unrestricted access to information. The law guarantees the protection of sources, but news organisations must be accountable. Professional associations represent a large proportion of journalists. The German Press Council (Deutscher Presserat) is a voluntary and self-monitoring press regulator which was established by the associations of journalists and of newspaper and magazine publishers. Emphasising a commitment to the freedom of the press, the German Press Council handles complaints from the public concerning possible violations of press standards. Despite the relative independence and professionalism of the field, increasing financial pressures on publishers are degrading working conditions and threatening job security for practitioners. Occasionally, as a result of political conflict, journalists are portrayed as being dishonest and, at times, they have been threatened with physical abuse.

For the independence of German regulatory authorities risks are negligible. [1] For print media, there are no special regulatory authorities besides the German Press Council. A broad stratum of society is represented at the board level of each public broadcaster so as to ensure a certain plurality of opinion, independent of any centralised authority. The degree of separation between public media and the state is, however, constantly under review. Recently, for example, the composition of the board of one broadcaster was subject to a decision by the German Constitutional Court that criticised an excessive representation of political power. Fourteen Regional Media Authorities (Landesmedienanstalten) externally control private broadcasters and digital services (Telemedien). These authorities have a legal guarantee of independence from political and commercial interference. Media companies are also subject to competition regulation by the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt), which is also independent. Its tasks, duties and responsibilities are defined in detail by law. The same is true for the communications regulator, the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur).

2.2 Market Plurality (44% risk – medium risk)

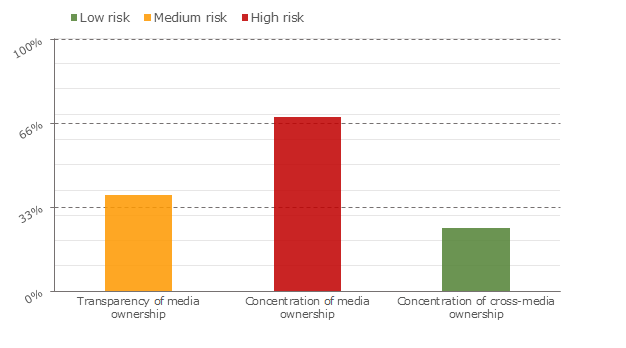

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess regulatory safeguards against high concentration of media ownership and control in the different media, within a media market as well as cross-ownership concentration within the media sector.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Transparency of media ownership | 38% risk (medium) |

| Concentration of media ownership | 69% risk (high) |

| Concentration of cross-media ownership | 25% risk (low) |

The indicators for the ‘Market Plurality’ domain lead to a more ambivalent assessment. The evaluation of ‘Transparency in media ownership‘ shows a medium risk (38%). There are no rules that particularly oblige media companies to publish their ownership structure to the public, but in many cases they take the legal form of incorporated companies and they are therefore obliged to publish financial reports to their shareholders. Broadcasters must publish annual reports, including notes of their annual accounts; they must report ownership structures and disclose the relevant information after every change in their ownership structure. However, according to the German Commission on Concentration in the Media (Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich) there is no complete and reliable documentation detailing the ownership of private radio companies.

The ‘Concentration in media ownership‘ indicator shows a high risk to media pluralism (69%). In order to prevent a predominating power of opinion there are normative provisions to prevent media concentration in audiovisual media, which is based on audience share. For radio, newspapers and Internet content providers there are no specific thresholds to prevent high levels of concentration. Media mergers, however, are also subject to German competition law, providing additional barriers to undesirable mergers and acquisition cases. The audience concentration of the TV market is very high. The Top4 (public broadcasters, RTL Group, ProSiebenSat.1, and Sky) achieve a market share of 90 percent of television viewing time. In contrast, the Top4 newspaper publishers have a 38% share of the total circulation.

The indicator ‘Concentration of cross-media ownership‘ scores a low risk (25%). The German Commission on the Concentration in the Media focuses on television, but, to a limited extent, also includes other relevant markets. The focus on television is often criticised for being outdated, and other criteria that include activities in other media are under discussion. The market share of the major eight firms across the different media sectors (if all the regional public broadcasters are counted as one) was 62 percent in 2013.

2.3 Political Independence (19% risk – low risk)

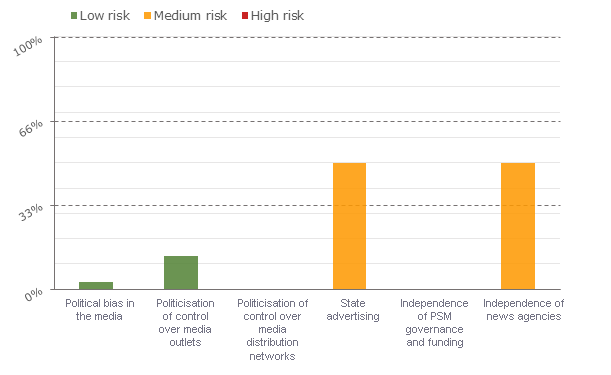

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of implementation of regulatory safeguards against biased representation of political viewpoints in the media, and also the extent of politicisation over media outlets, media distribution networks and news agencies. Moreover, it examines influence of the state on the functioning of the media market, with a focus on state advertisement and public service media.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Political bias in the media | 3% risk (low) |

| Politicisation of control over media outlets | 12% risk (low) |

| Politicisation of control over media distribution networks | Negligible |

| State advertising | 50% risk (medium) |

| Independence of PSM governance and funding | Negligible |

| Independence of news agencies | 50% risk (medium) |

According to recent studies there is no distinctive political bias in the German public service media and commercial broadcasting (indicator ‘Political bias in the media‘: 3% – low risk). The broadcasting remit is defined by law. Public service broadcasters are supposed to act as a medium and as a factor in the process of the formation of free individual and public opinion through the production and transmission of their services, thereby serving the democratic, social and cultural needs of society. Through their content, public service broadcasters must provide a comprehensive overview of international, European, national and regional events in all major areas of life. The idea is that, in so doing, the media will contribute to further international understanding, European integration and social cohesion on both a federal and a state level.

In Germany there is almost no ‘Politicisation of control over media outlets‘ (2% – low risk). All political parties have to present a statement about their shares in media companies to the president of the national parliament, and these statements are published. As far as national broadcasting channels are concerned, political parties are not allowed to obtain a licence by law.

There is no substantial ‘Politicisation of control over media distribution networks’ either (negligible risk for the connected indicator). Print media distribution is mostly operated by regional wholesalers with regional monopolies in most regions. In 1969, the Constitutional Court decided that publishers are not allowed to prevent the delivery of their publications to dealers in order to prevent them distributing a competitor’s TV guide. In an agreement with the associations of newspaper publishers (BDZV Bundesverband Deutscher Zeitungsverleger) and magazine publishers (VDZ Verband Deutscher Zeitschriftenverleger), the print media wholesalers association (BVPG Bundesverband Deutscher Buch-, Zeitungs- und Zeitschriften-Grossisten) has agreed that they must be neutral towards all print publishers and their products. The distribution of radio and television is not politicised at all.

The indicator ‘State advertising‘ scored a rating of medium risk (50%), because there are no transparent rules for the distribution of state advertising. There are no detailed data about state advertising, but the statistics that are available suggest that state advertising does not have a significant share of the advertising market.

The ‘Independence of public service governance and funding‘ is not at risk in Germany (negligible risk for the indicator ‘independence of PSM governance and funding’). Fair, objective and transparent procedures for management and board functions guarantee independence from government or from any single political group. For this reason, the Federal Constitutional Court recently decided that the rules for the board of ZDF, the nationwide public service TV corporation, must be changed. Wages are negotiated between the public broadcasters and the unions. The level of license fees for public broadcasters is specified by an interstate treaty of the federal states which is based on the recommendation of the commission for the determination of the financial needs of public broadcasters (KEF Kommission zur Ermittlung des Finanzbedarfs der Rundfunkanstalten).

The indicator ‘Independence of news agencies‘ attests a medium risk (50%). In 2013, the leading news agency (dpa, Deutsche Presse-Agentur) was subscribed to by all of the German newspapers, as well as all national, and most regional, broadcasters. The shareholders of DPA are its customers, comprising 187 print publishers and public and private broadcasters. None of them hold more than a 1.5 percent share in the agency. The association of German language news agencies has nine members in total (including the national news agencies of Austria and Switzerland), with most of them being used as secondary, special interest news sources.

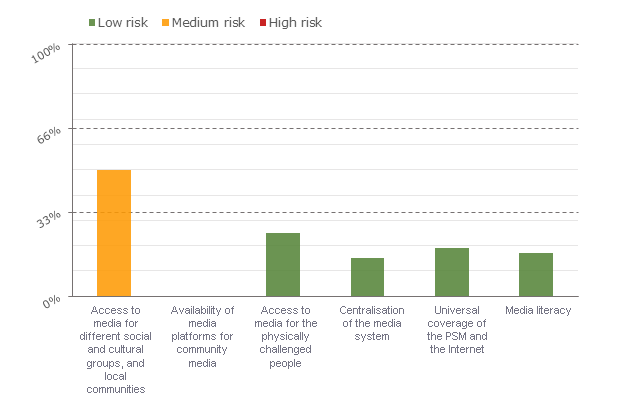

2.4 Social Inclusiveness (21% risk – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to and availability of media for different, and particularly vulnerable, groups of population. They assess regulatory and policy safeguards for access to media by various cultural and social groups, by local communities and by people with disabilities. Moreover, they assess the centralisation of the media system, and the quality of the country’s media literacy policy, as well as the digital media skills of the population.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Access to media for different social and cultural groups, and local communities | 50% risk (medium) |

| Availability of media platforms for community media | Negligible |

| Access to media for the physically challenged people | 25% risk (low) |

| Centralisation of the media system | 15% risk (low) |

| Universal coverage of the PSM and the Internet | 19% risk (low) |

| Media literacy | 17% risk (low) |

Most of the indicators in the ‘Social Inclusiveness’ domain show a low risk. The only indicator with medium risk is ‘Access to media for different social and cultural groups and local communities‘ (50%), because there is no access to airtime on PSM that is guaranteed by law to different social and cultural groups, except churches and Jewish communities. However, many different groups are involved in the supervisory boards of the public service broadcasters. Most public broadcasters are regional, often with special studios for smaller territories within their broadcasting areas.

A requirement to provide community media platforms is stipulated by law in most states as a way of enhancing plurality (‘Availability of media platforms for community media‘: negligible risk). There are no legally established special television or radio channels for minorities. For physically challenged people, the policy on access to media content is well-developed (Indicator: ‘Access to media for physically challenged people‘: 25%).

The risk of centralisation of the German media system is low (fourth indicator: 15%). Public and commercial broadcasting are regulated by federal state law and provide some degree of regional programming for radio and television. Most newspapers are regional, but there is no special legislation for local newspapers.

‘Universal coverage by PSM‘ is guaranteed by the Constitution and is realised, in practice, for radio and television (19% for the fifth indicator). Broadband coverage includes most of the rural population (99%); while broadband penetration in Germany was 81% in 2013.

‘Media literacy‘ (17% – low risk) is an ongoing issue for the federal states (and their media authorities) as well as for the federal government. They are mostly concerned with media literacy of children. According to the EU Digital Agenda Scoreboard, more than 50% of the population had at least basic digital skills in 2014.

Our external reviewer would like you to add a sentence or two about minorities that are not officially recognised as such (e.g. Turkish community). What is the reason for them not having German citizenship? Are these minorities served by community media?

3. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the MPM2015, the following issues have been identified by the country team as more pressing or deserving particular attention by policy-makers in order to promote media pluralism and media freedom in the country. .

The protection of the pluralism of the mass media in Germany is a major achievement of media regulation and the monitoring of the legal framework by the German Constitutional Court. It is imperative that politicians resist the temptation to change the media system for their own benefit. Recent history shows that it is essential that Germany has a Constitutional Court that can protect fundamental rights from the whims of party politics.

The results of this pilot implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor indicate that the main risk to media plurality in Germany is the concentration of media ownership. Media regulators and politicians have been aware of this issue for many years. It is recommended that the transparency of media concentration should be enhanced, and that the regulation of media concentration is developed further in relation to developments in Internet-based media. Media legislation still focuses on television, and it is, at the very least, questionable whether the old idea of television as a dominant medium can be sustained. Legislation is significantly influenced by European law, so the scope of actions at a national level is limited.

Annex I. List of consulted national experts

Sven Pagel – Univ. of Applied Sciences, Mainz

Michael Brüggemann – University of Hamburg

Katharina Kleinen-von Königslöw – University of Zurich, IPMZ – Institut für Publizistikwissenschaft und Medien

Dietmar Wolff – BDZV Bundesverband Deutscher Zeitungsverleger

Claus Grewenig – VPRT Verband Privater Rundfunk und Telemedien

[1] NB: It needs to be noted that this indicator has been found to be problematic in the 2015 implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor. The indicator aimed to combine the risks to the independence and effectiveness of media authorities, competition authorities and communication authorities was found to produce unreliable findings. In particular, despite significant problems with regard to the independence and effectiveness of the authorities in many countries, the indicator failed to pick up on such risks and produced and overall low level of risk for all countries. The indicator will be revised for further versions of the MPM (note by CMPF).