Author: Josef Seethaler (Austrian Academy of Sciences) [1]

October 2015

1. Introduction

After a long period of relatively stable market conditions, the Austrian media system is undergoing profound changes. In the last decade, the dual system of public and private broadcasters, introduced as late as 2001, has led to a decline in the audience share of Public Service Broadcasting, while the growing market share of free daily newspapers has intensified the competition in the newspaper industry. In contrast to the delayed introduction of the dual broadcasting system, new communication technologies have diffused rapidly throughout the country, and the use of online media, particularly of social network services, is rising dramatically. The print media is characterised by a small number of large, nationally distributed newspapers and magazines, a few regional newspapers, particularly distributed in the Western and Southern provinces, and a declining degree of concentration of ownership in a former highly concentrated market. At the same time, cross-media concentration is on the rise (Lohmann & Seethaler 2016 [1]).

2. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

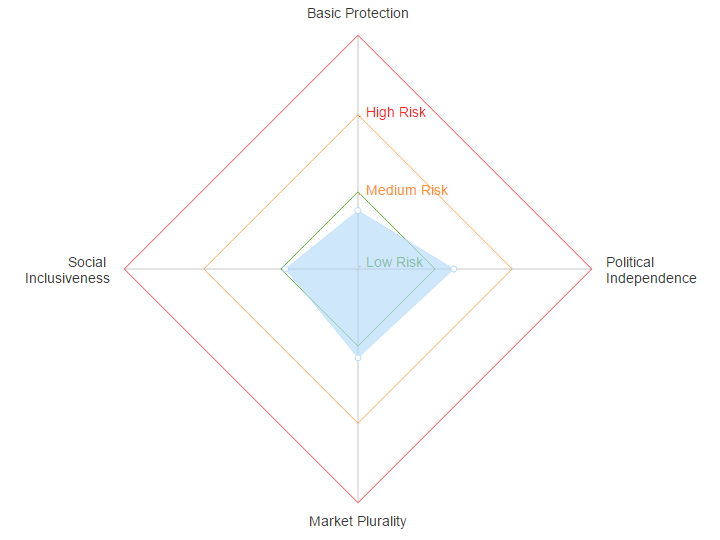

The implementation of the MPM2015 for Austria seems to indicate low and medium risks for media pluralism in the country. Two domains (‘Basic Protection’ and ‘Social Inclusiveness’) score low risk, while the other two (‘Market Plurality’ and ‘Political Independence’) score medium risk. Furthermore, 11 of 19 indicators assess a medium or high risk. Risks to media pluralism in Austria are primarily due to the lack of protection for the right to information, the politicisation of control over media outlets, political bias in the media, the concentration and lack of transparency in media ownership, influence over the financing of publicly supported media, limited access to the media of different social and cultural groups, and the tendency to the centralisation of the media system. There are also insufficiencies in broadband coverage.

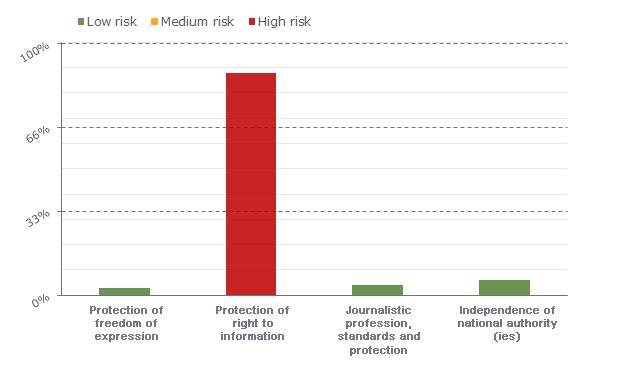

2.1 Basic Protection (25% risk – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy and they measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; as well as the independence and effectiveness of national regulatory bodies, namely media authorities, competition authorities and communications authorities.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Protection of freedom of expression | 3% risk (low) |

| Protection of right to information | 88% risk (high) |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | 4% risk (low) |

| Independence of national authority(ies) | 6% risk (low) |

The MPM analysis shows that freedom of expression is well protected in Austria (low risk). Freedom of expression is recognized in Article 13 of the December Constitution of 1867, to which the Austrian Federal Constitution of 1930 refers to in Article 149. Austria ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), protecting freedom of expression in Article 10, in 1958. Since 1964, the Convention is part of the Austrian constitution, and all restrictions are in accordance with Article 10 ECHR. In addition, Austria ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICCPR in 1978, but regulations of implementation are still missing.

In case of violations of freedom of expression a citizen may appeal to the Austrian Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights. Today, the legal remedies against violations of freedom of expression can be considered as effective; however, in prior years, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has overturned a considerable number of national courts’ decisions. To date, there have been no serious violations of freedom of expression online.

Regarding the sensitive question of criminalisation of defamation, Article 111 of the Austrian Criminal Code allows for increased prison sentence for defamation and insult (there is a separate ‘insult’ law in addition to libel laws), when defamation has been made accessible to a wider public by means of the mass media, particularly in cases of insult to state symbols. Moreover, Article 6 of the 1981 Media Act provides for strict liability of the publisher. On the other hand, according to a 2014 report by the International Press Institute, there are specific clauses in law protecting journalists from liability as long as they have observed basic journalistic duties (Article 29 of the 1981 Media Act), and Austria is one of only two EU countries, which currently provide statutory caps on non-pecuniary damages in defamation cases involving the media.

The MPM results point to a high risk regarding the protection of right to information. Article 20(4) of the Federal Constitution states that there is a right to information. However, the obligation of administrative authorities to maintain secrecy has precedence. In case of denial to access information, there is only the right to lodge a judicial appeal with the Federal Administrative Court, in line with the General Administrative Procedures Act. However, there are no clear procedures (including timelines) in place for dealing with such appeals; in the appeal process the government does not bear the burden of demonstrating that it did not operate in breach of the rules; requesters have no right to lodge an external appeal with an independent administrative oversight body. In line with the high risk score revealed by the MPM, the situation concerning the right to information was considered the worst among 103 countries in a 2013 study done by Access Info Europe and the Centre for Law and Democracy.[3]

The indicator ‘Journalistic profession, standards and protection’ scores a low risk. Access to the journalistic profession is free and open. In a corporatist country like Austria, a broad section of journalists are represented by professional associations, but the organizational degree of Austrian journalism is in steady decline: from a representation of over 85% in the 1970s to slightly more than 40% in the last years. In the Journalistic Code of Ethics it is stated that economic interests of the owner of the media company should not influence editorial work; however, there is no recent data available on journalists’ perceived influences of media owners or commercial entities. Due to increasing economic pressure, social and job insecurity are on the rise. There are no cases of attacks or threats to the physical or the digital safety of journalists. Article 31 of the Media Act 1981 provides strong protection for the confidentiality of journalists’ sources. So far, there is no specific whistleblowing legislation in Austria.

The indicator ‘Independence and effectiveness of national authority’ scores a low risk.[4] In 2001, the Austrian Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications (RTR) was established. RTR consists of two divisions (Media Division and Telecommunications and Postal Service Division) and provides operational support for the Austrian Communications Authority (KommAustria), the Telekom-Control-Commission (TKK) and the Post-Control-Commission (PCK). They all are separate legal entities, and fully independent from the government. Appointment procedures are transparent; duties and responsibilities are defined in detail in the law. KommAustria has regulatory and sanctuary powers. Decisions must be published and can be appealed before the Federal Administrative Court. RTR is financed by the markets as well as by federal funding, depending on the kind of activities. The organization’s business operations and annual financial statements are reviewed by external auditors. Its transparent work (and the independent status) has made KommAustria/RTR highly respected.

One of the central tasks of the Federal Competition Authority (established in 2002) is examining notifiable mergers according to competition law. It can apply fines at the cartel court. In this regards the Authority’s decisions can affect the media market. Appeals of its decisions have to be addressed to the Independent Administrative Chamber. The members of the Federal Competition Authority are appointed by the Ministry of Economics and several corporatist organizations; rules on incompatibility have to be observed (according to the 1983 Act on Incompatibilities). The Director General is independent from orders of the ministry. Unfortunately, funding of the competition authority is not specified in law in accordance with a clearly defined plan, and it was sometimes criticized as being somewhat insufficient.

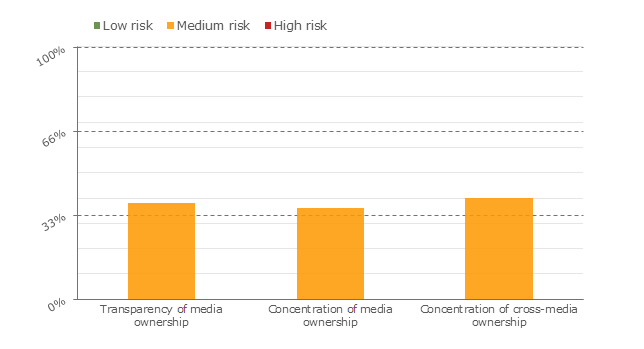

2.2 Market Plurality (38% risk – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess regulatory safeguards against high concentration of media ownership and control in the different media, within a media market as well as cross-ownership concentration within the media sector.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Transparency of media ownership | 38% risk (medium) |

| Concentration of media ownership | 36% risk (medium) |

| Concentration of cross-media ownership | 40% risk (medium) |

All three indicators in the ‘Market Plurality’ domain show medium risk. In terms of transparency of media ownership, Media companies are obliged to publish their ownership structures on their website or in records/documents that are accessible to the public. This information has to be updated every year. Media law provides for administrative penalties to be imposed on companies that do not disclose information on their ownership structure. Nevertheless, some shareholders or investors and/or the amount of their investment (sometimes when banks are involved) remain unknown.

Concerning ‘Concentration of media ownership’, the legislation for the audiovisual and radio sectors contains specific restrictions regarding areas of distribution to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration. However, these restrictions are not so tight, because – according to the private radio law and the private television law of 2001 – a media company is allowed to own several radio or TV stations if the areas of distribution do not overlap – even when the whole area of Austria is covered by these stations. The market share of the Top 4 audiovisual media owners is 56% (including foreign television stations with special ‘Austrian windows; without foreign television stations with special ‘Austrian windows’: 99%); the market share of the Top 4 radio owners is 93%. Audience concentration for the audiovisual media market is 43%, for the radio market 52% (2014). The market share of the Top 4 newspapers owners is 81%; readership concentration for the newspaper market is 71% (2013). Although cartel law includes particular rules concerning the plurality of the media, however, it was, at least in the past, ineffective in preventing mergers of big media companies (1988: ‘Mediaprint’; 2001: ‘Formil’-Deal). Unfortunately, no data are available on market shares, either for the TOP 4 Internet Service Providers, or for the TOP 4 Internet content provider owners.

In terms of the ‘Concentration of cross-media ownership’, in addition to the aforementioned restrictions regarding areas of distribution so as to prevent cross-media concentration, media companies that control more than 30% of the newspaper, magazine or radio market are not allowed to own a TV station. There is no similar regulation in the radio sector, thus opening the door for (almost all) Austrian provincial newspaper publishers to acquire regional and local radio channels. There is therefore quite a high degree of cross-ownership in the radio and newspaper sector.

Unfortunately, due to insufficient data, the ratio between the TOP 8 revenues across the different media sectors, and the whole revenue market across media sectors cannot be calculated. Based on estimates by the Austrian daily newspaper ‘Der Standard’, the eight biggest media companies make up 76% of the revenues of the 19 most important media companies.

2.3 Political Independence (41% risk – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of implementation of regulatory safeguards against biased representation of political viewpoints in the media, and also the extent of politicisation over media outlets, media distribution networks and news agencies. Moreover, it examines influence of the state on the functioning of the media market, with a focus on state advertisement and public service media.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Political bias in the media | 39% risk (medium) |

| Politicisation of control over media outlets | 50% risk (medium) |

| Politicisation of control over media distribution networks | Negligible |

| State advertising | 58% risk (medium) |

| Independence of PSM governance and funding | 50% risk (medium) |

| Independence of news agencies | 50% risk (medium) |

The indicator on ‘Political bias in the media‘ shows medium risk. Media law imposes rules aiming at fair, balanced and impartial representation of political viewpoints in news programmes on PSM channels. The ‘Publikumsrat’ (Viewers’ and Listeners’ Council) is tasked to actively monitor compliance with these rules and to hear complaints, but it does not have sufficient sanctioning powers. Besides the legal obligations, in 2009, ORF implemented a quality-safeguarding system. Nevertheless, from time to time, there is public debate about whether ORF fulfils its obligation to create objective and well-balanced content.

Since 2002, political advertising in PSM is not allowed during election campaigns. Buying political advertising is allowed only in private channels. Equal conditions have to be guaranteed because of Article 7 of the Federal Constitution, which refers to the principle of equal opportunities for all political parties.

No obligation for fair, balanced and impartial reporting is mentioned in the Code of Ethics for the Austrian Press, which was first adopted in 1983 by the Austrian Press Council, and which was amended in January 1999. Actually, several content analyses provide evidence of some bias in political coverage on commercial channels and newspapers, whereas PSM channels offer a more balanced and impartial representation of the various political parties (Seethaler & Melischek 2014).

The indicator on the ‘Politicisation of control over media outlets‘ indicates medium risk. There is no TV or radio channel owned and/or controlled by a specific political group, and the share of newspapers owned by politically affiliated entities is only 0.5% (2013). Some media owners may have political affiliations. However, there is currently no systematic research on this topic and the related data is not publicly available.

The two largest radio channels and the two largest TV channels (all PSM) have editorial statutes in place. Unfortunately, this does not apply to the two largest newspapers that, moreover, are not members of the Austrian Press Council.

The risk of the ‘Politicisation of control over media distribution networks‘ is coded as negligible risk. However, the author underlines that this aspect of media pluralism cannot be fully assessed due to lack of studies relating to political affiliations and control over media distribution networks.

The indicator on state advertising show medium risk. According to the 2012 law on the transparency of media advertising and sponsoring, the government, public bodies and state-owned corporations are obliged to disclose their relations with the media (through advertisements and other kinds of support) each quarter. The Austrian regulatory authority KommAustria is required to publish the information, including the total amount paid to each named media company, on a quarterly basis. The National Court of Auditors has to check whether the published information is complete.

No reliable data is available on the share of state advertising as part of the overall TV, radio or newspaper advertising market. Nevertheless, there is public discussion about questionable practices in state advertising, because advertising orders are mainly given to a few important media outlets, but are not distributed amongst all media outlets (proportionally to their audience shares). From the viewpoint of liberal democracy, this seems to be problematic, because political autonomy is considered a necessary prerequisite for the functioning of the media system. The ‘Independence of PSM governance‘ and funding is also assessed as being at medium risk. The law provides fair, objective and transparent appointment procedures for the management and the board functions in PSM, but there is no administrative or judicial body tasked with actively monitoring the compliance with these rules and/or hearing complaints. On several occasions, conflicts have been publicly discussed concerning the appointments and dismissals of managers and board members of PSM, because of political/governmental attempts to influence these appointments.

The wages of PSM employees are specified in collective bargaining agreements. Due to missing legal regulations, provincial governors are allowed to use license fees partly for a purpose other than the one originally intended, but there is no direct government financing for the PSM.

The indicator on ‘Independence of news agencies‘ shows medium risk: There is only one big news agency in Austria (and this is the only reason why the MPM score indicates a ‘medium risk’): the Austrian Press Agency (APA), founded in 1946 as a co-operative of almost all Austrian newspapers and the ORF. It is independent from political groups in terms of ownership, the affiliation of key personnel, or of editorial policy – and it is, therefore, highly respected. Besides APA, there are only very small, specialized news agencies, like ‘Pressetext’ and ‘Kathpress’ (with the latter belonging to the Catholic church).

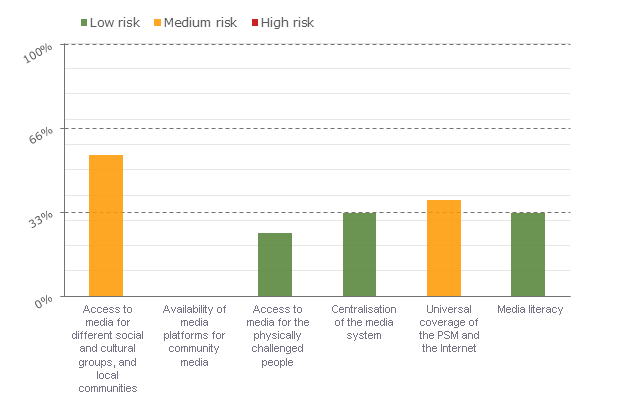

2.4 Social Inclusiveness (31% risk – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to and availability of media for different, and particularly vulnerable, groups of population. They assess regulatory and policy safeguards for access to media by various cultural and social groups, by local communities and by people with disabilities. Moreover, they assess the centralisation of the media system, and the quality of the country’s media literacy policy, as well as the digital media skills of the population.

| Indicator | Risk |

| Access to media for different social and cultural groups, and local communities | 56% risk (medium) |

| Availability of media platforms for community media | negligible |

| Access to media for the physically challenged people | 25% risk (low) |

| Centralisation of the media system | 33% risk (low) |

| Universal coverage of the PSM and the Internet | 38% risk (medium) |

| Media literacy | 33% risk (low) |

The indicator on the ‘Access to media for different social and cultural groups‘, and local communities shows a medium risk. According to the 1984 ORF law, the Austrian Public Service Broadcaster should consider the concerns of all age groups, of physically challenged persons, of families, of both sexes, and of all churches ‘in a reasonable way’. There is no similar obligation for all other media organizations, and there is no due monitoring and sanctioning system for access to airtime by different social and cultural groups. Moreover, the ORF is neither obliged to have a minimum proportion of regional or local communities involved in the production and distribution of content, nor does it have to keep its own local correspondents or to have a balance of journalists from different geographical areas.

Only six linguistic minorities (defined as ‘autochthonous groups’ in the law) are legally recognized in Austria, and these minorities all fall below the MPM threshold of 1% of the population. The indicator on the ‘Availability of media platforms for community media‘ is coded as negligible risk. In general, the role of community media in society is acknowledged, but not as third-tier broadcasting by the Austrian Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications (RTR). The independence of community media is fostered insofar as it is defined as being a precondition for subsidies. However, there is some risk related to minority media, which are supported as part of community media in Austria. Although a more significant representation of minority members as radio producers and program makers has started since the liberalization of the broadcasting legislation in the late 1990s, the existing legal situation is not sufficient for a successful development of minority media. For example, in a ruling from 2012, the Austrian Constitutional Court found that there is no right for the Slovenian minority media to have access to radio and TV networks.

The indicator on ‘Access to media for physically challenged people‘ shows a low risk. The beginning of state policy regarding access to media content by physically challenged persons dates back only to 2009 and is, so far, limited to public service television. Subtitles and sound descriptions are available for 65% of ORF’s programmes.

The ‘Centralisation of the media system‘ is also at low risk. Regarding the printed press, the Press Subsidies Act of 2004 provides special subsidies for the preservation of diversity in regional daily newspapers. However, the amount of press subsidies, as a share of the GNP, is decreasing. Due to the most recent cuts in press subsidies, one of the few regional daily newspapers had to cease publication. Regional newspapers account for only 24% of the total circulation of Austrian newspapers (2013).

Regarding the radio market, private radio stations are primarily regional in their scope (the overwhelming majority of frequencies are reserved for regional radio channels). Public regional radio stations account for a considerable amount (35%) of the entire radio market, and private regional/local radio stations for an additional 16% (2014). Regarding the television market, there are only very small regional/local TV stations in Austria. No audience share data are available.

The indicator on the ‘Universal coverage of the PSM and the Internet‘ shows a medium risk. Almost the whole Austrian population is covered by signals of the public TV and radio channels. Although broadband coverage is similarly high, the subscription rate is only 77%, and broadband speed is below 30Mbps (download) and 10Mbps (upload). Particularly the latter figure can be regarded as being extremely low.

The ‘Media literacy’ indicator shows a low risk. There are a lot of federal and local initiatives to foster media literacy; however, there is no well-developed policy on media literacy. For example, it is not compulsory in school curricula to learn how to use media effectively. According to Eurostat data, almost 80% of the Austrians are using the internet at least once a week, but about 37% have insufficient digital skills.

3. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the MPM2015, the following issues have been identified by the country team as more pressing or deserving particular attention by policy-makers in order to promote media pluralism and media freedom in the country.

In comparing the quality of the laws on the right to information (RTI), Access Info Europe (AIE) and the Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD) have ranked Austria last of 103 countries worldwide. Presently, the relevant Act regulates the right to apply for information, but it does not guarantee a general right of access. Hence, state bodies can refuse to provide information without having to justify their decision. To address this legislative gap, the Council of Europe has recommended that Austria provide for precise criteria in a limited number of situations where access to information can be denied, and to ensure that such denials can be challenged by the person concerned (Council of Europe 2012). Based on these findings and on the MPM2015 analysis, the author recommends the government to improve the RTI law. Furthermore, a lot of the data are not easily publicly available, for example, regarding cross-media concentration, the share of state advertising as part of the overall TV/radio/newspaper advertising market, and the market shares of ISPs and Internet content providers. The author suggests that government address this lack of transparency, on the one hand, by imposing information duties on the actors in the various sectors, and, on the other, by guaranteeing information rights and supporting research on these matters.

In recent years, the Austrian media system has become more diverse and concentration among the various media markets is declining. However, some of the regulations of the private radio law and private television law are fostering cross-media concentration. Moreover, little is known about the possible impact of state and political actors (through attempts to influence the appointment procedures for management and board functions in PSB, and the allocation of advertising) as well as of commercial entities (particularly banks) on media content. Self-regulatory measures (like editorial statutes) that stipulate editorial independence and foster internal plurality should therefore be obligatory for all media houses. In general (and in addition to the work of KommAustria and RTR), the author suggests introducing more effective monitoring of compliance with the existing rules in media governance, for example, regarding the appointment procedures at ORF, the transparency of ownership, and access to airtime, of different social and cultural groups.

Moreover, the MPM analysis has revealed that local community media, which is an increasingly important media sector in today’s democratic society, would benefit from more support from the government. In addition to the important role that local community media play for increased accountability to the public, more government support is imperative, because openness to participation by members of the community for the creation of media content will become a highly important feature in future media production. For the same reason, legally restricted use of social online networks by legacy media outlets should be reassessed.

In addition, the government should consider measures to improve the legal environment for the development and functioning of minority media. Finally, the government should develop an effective policy aimed at making media literacy a key component of the mandatory school curriculum.

Annex I. List of consulted national experts

Walter Berka – University of Salzburg

Alexandra Föderl-Schmid – “Der Standard”, IPI

Dieter Henrich – Verband der Regionalmedien Österreichs (VRM)

Daniela Kraus – Forum journalismus und medien

Helga Schwarzwald – Association of Community Radios

Christian Steininger – University of Vienna

References

Council of Europe 2012. Joint First and Second Evaluation Round Addendum to the Compliance Report on Austria Adopted by Council of Europe Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) at its 56th Plenary Meeting (Strasbourg, 20-22 June 2012). https://www.coe.int/Lohmann, M I & Seethaler, J 2016, ‘Medienkonzentration in Österreich im 21. Jahrhundert [Media concentration in Austria in the 21st century]’, in Media Perspektiven, forthcoming.

Lohmann, M I & Seethaler, J 2016, ‘Medienkonzentration in Österreich im 21. Jahrhundert [Media concentration in Austria in the 21st century]’, in Media Perspektiven, forthcoming.

Seethaler, J & Melischek, G 2014, ‘Phases of mediatization: Empirical evidence from Austrian election campaigns since 1970’, in Journalism Practice, 8(3): 258–278. DOI:10.1080/17512786.2014.889443

[1] Data collection was carried out with the help of Maren Beaufort, MA.

[2] All data on market shares and concentration rates mentioned in this paper are based on this study.

[3] https://www.rti-rating.org/country-data

[4] NB: It needs to be noted that this indicator has been found to be problematic in the 2015 implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor. The indicator aimed to combine the risks to the independence and effectiveness of media authorities, competition authorities and communication authorities and it was found to produce unreliable findings. In particular, despite significant problems with regard to the independence and effectiveness of the authorities in many countries, the indicator failed to pick up on such risks and produced and overall low level of risk for all countries. The indicator will be revised for further versions of the MPM (note by CMPF).