Read more

News

New book marks a decade of research on media pluralism in Europe

After ten years of in-depth research conducted under the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) project, the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom has published Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Legal, Economic, Social, and...

Iva Nenadić

A month and a half after the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) entered into force, the new Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM2024) for all EU member states and 5 candidate countries was published. The MPM has been implemented incrementally and regularly since 2014, resulting in the largest systematic recording of conditions and risks to media freedom and pluralism across the EU and beyond. As such, the MPM provides evidence of how much the situation for journalism and media in Europe has changed over the last decade, and not for the better.

Monitoring risks to media pluralism led to the EMFA, and ongoing monitoring is expected to be a crucial ingredient in the implementation of this EU law. The application of EMFA will begin in August 2025. Therefore, this is the perfect time to thoroughly analyse the conditions for media freedom and pluralism in the EU and its prospective member countries, which will mark the starting point for EMFA’s implementation. This post highlights the main structural risks and shortcomings recorded by the MPM across its four dimensions of measurement: fundamental protections, market plurality, political independence, and social inclusiveness. But before delving into the results, let’s unpack the concept of media pluralism: what it is and what purpose it serves?

Media pluralism is a complex and constantly evolving concept, grounded in the constitutional value of freedom of expression, to which media freedom is integral. It encompasses a set of structural conditions in a democratic society and its information sphere, which limit the unwanted influences of those holding communicative, economic, or political power. Additionally, it encourages sustainability, development, independence, and diversity in the media.

Media pluralism is not an end in itself. Free, diverse, economically vital, innovative, and quality media and journalism are the foundations of an informed citizenry. This is particularly important during pivotal moments like elections, health crises, or climate emergencies, when citizens need access to diverse, relevant, and reliable information. Such information and should encompass and represent various social groups, especially those in vulnerable conditions. Furthermore, when journalists operate within an enabling environment, they ought to be safer in performing their watchdog function over centers of power and any misuse of public resources for personal gains. Media pluralism is thus beneficial for democracy, economy, and humanity.

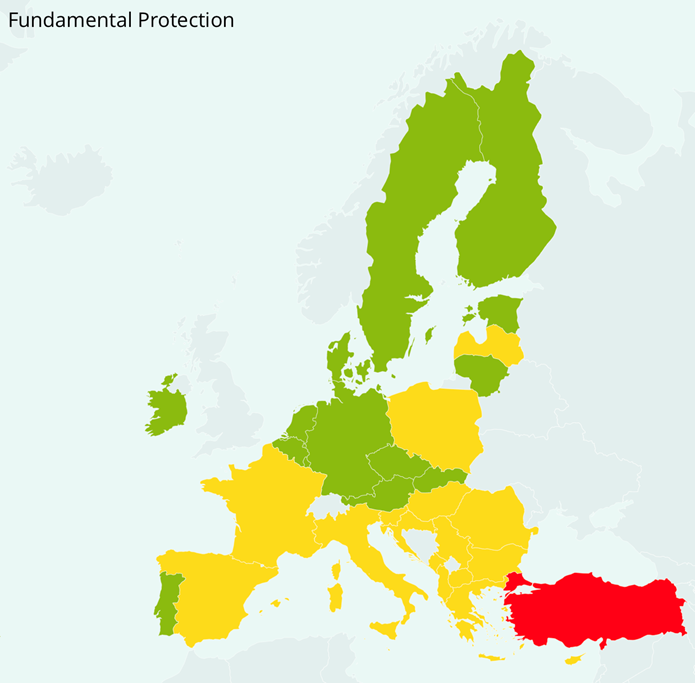

Throughout the years, the MPM has indicated a number of structural risks to media freedom and pluralism, starting from the protection of fundamental rights and conditions for journalists to conduct their job safely and abiding the professional standards. In the MPM2024, the area of Fundamental protection scores the lowest risk level compared to the other three areas (Market plurality, Political independence, Social inclusiveness), but still in the medium risk. This is the aggregate result for all 32 countries covered by the project. As indicated on the map below and detailed in country-specific reports, the situation varies significantly across states. Yet, the result is concerning because this area evaluates aspects that are fundamental to ensuring freedom of expression, access to information, the professional status and safety of journalists, the independence and effectiveness of media authorities, and universal access to the media.

The increased risk in Fundamental protection is primarily attributed to the indicator of Journalistic profession, standards, and protection. Working conditions for journalists are continuously deteriorating. Furthermore, the safety of journalists in the EU has been worrying since the assassination of Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017, whose murder has not been fully solved even after seven years. There have been no cases of killings of journalists in the EU during the last MPM implementation, but after Caruana Galizia, journalists were murdered in several EU member states, namely, Slovakia, Greece, and the Netherlands. Increasingly hostile environment for journalists, often encouraged by influential politicians, spans both physical and online dimension. In the MPM2024, digital safety of journalists is scoring a high risk as online abuses against journalists have been on the rise in many of the countries assessed. Threats of violence, which are typically made online, have become increasingly common in recent years. As public figures, journalists face public threats on social media platforms or via their private email and messages. In some cases, the attacks against journalists appear to be organised. Individual journalists are singled out online, exposed to smear campaigns and other intimidations, including through a network of automated accounts (bots) and other technologies. When evaluating safety of journalist, the MPM also considers the gender dimension. The findings show that, as a rule, female journalists are at higher risk than their male colleagues.

Market plurality is the highest scoring area of the MPM. The indicators in this area evaluate the economic dimension of media pluralism, including transparency of media ownership and market concentration in terms of both production (media companies) and distribution (increasingly designed by a few global online platforms). The results in this area also reflect the potential for the media sector and journalism to ensure economic viability and sustainable innovation amidst the digital transformation. Finally, market plurality and the right of citizens to access accurate and independent information are also determined by how well editorial independence is shielded from undue commercial and owners’ influence.

As per the MPM2024 results, no country performs with low risk in this area. In fact, and regardless of the historical differences among the national media systems, the results of the Market area have always been the highest across all the areas of the MPM. There is a structural tendency towards concentration in the media markets, and an even higher tendency towards dominance in data-driven digital markets. The MPM also notes the deteriorating economic conditions in traditional media markets, which have not yet been offset by digital innovations in products, organization, and business models.

While the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) introduces new mechanisms to safeguard and strengthen editorial autonomy in the media, in the MPM2024 the indicator of Editorial independence from commercial and owners influence has, for the first time, shifted from medium to high risk. This change is partly due to methodological updates that aim to provide a more nuanced assessment of this risk, in line with the European Commission’s Recommendation on internal safeguards for editorial independence and ownership transparency in the media sector, which should contribute to the enforcement of the EMFA. Nevertheless, the overall high risk to editorial independence from commercial pressures is a worrying indication that economically vulnerable journalism lacks effective instruments to shield its professional standards from undue interference by advertisers and owners.

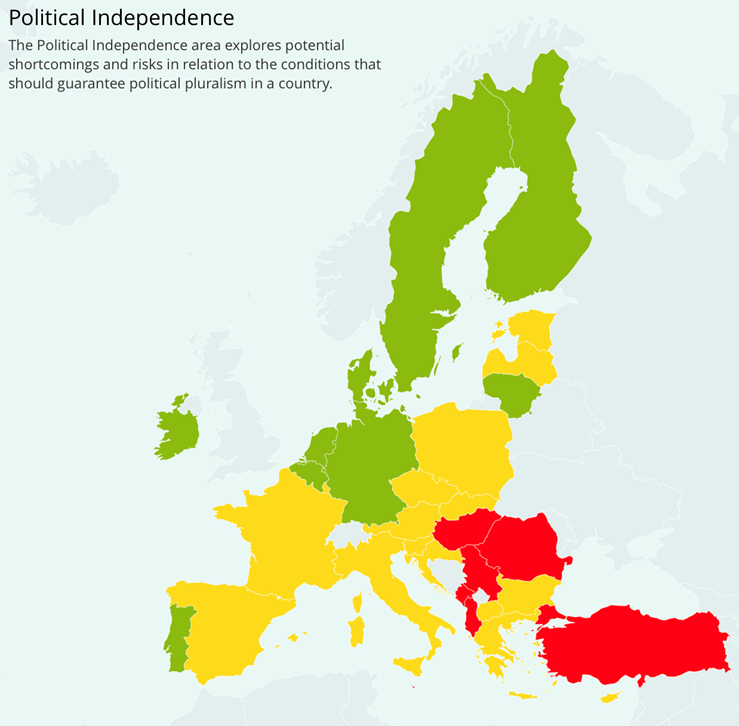

The commercial pressures to editorial autonomy operate hand in hand with undue political interference. This is elaborated in the Political independence area of the Media Pluralism Monitor, where Editorial autonomy – or better to say a lack of it – stands out as the highest risk overall. The structural risks to political independence of the media, including through both direct and indirect politicisation of media ownership, biased and non-transparent allocation of resources and subsidies to the media, misuse of state advertising, and political control over the public service media, have been rather stable throughout the decade of the MPM. For instance, in 15 EU member states, existing laws are not ensuring independence from government or other political influence in the appointment procedures for management and board functions in public service media. This inability or lack of political will to tackle this problem at the national level has led to it being addressed through the European media law.

Similar is the case with state advertising, which is any advertising paid for by or on behalf of a state. ‘State’ in this context includes a wide range of public authorities or entities, such as governments, regulatory authorities or bodies, state-owned enterprises, or other state-controlled entities across various sectors at the national, regional, or local level. This indicator has been part of the Media Pluralism Monitor’s assessment since its inception in 2014, recognizing that such advertising can be a key revenue source for media in some countries, especially during economically challenging times. Therefore, it is crucial to have clear rules on its distribution and transparency of the overall process. Without transparency, state advertising, as state buying in the media, poses risks of political capture and market competition distortion. As EU member states still predominantly don’t have rules to ensure transparency of state advertising, this has now become an obligation under EMFA.

Social inclusiveness examines the representation in the media, both in terms of media organisations and media content, of diverse groups, including minorities, local and regional communities, and women. It also evaluates the accessibility of news content for people with disabilities and media literacy as a precondition for effectively using the media. Regarding the safe use of media and the information environment as a safe space, this area also evaluates efforts against disinformation and hate speech.

One of the highest scoring indicators in the MPM over the years remains to be gender equality in the media, where only two countries: Denmark and Sweden, perform within a low risk in the MPM2024. Even if gender equality is a fundamental value and a strategic objective of the EU, in some countries there seem to be no interest in the question on the representation of women in the media, as noted in the MPM2024 final report.

The economic situation is difficult for journalism overall, but particularly challenging for local media and their survival. This significantly affects media pluralism as proximity is one of the key values defining newsworthiness and the impact of news on individuals and communities. The MPM indicator on Local, regional, and community media has served as a basis for a deeper analysis of “news deserts” in the EU, defined as “geographic or administrative area, or a social community, where it is difficult or impossible to access sufficient, reliable, diverse information from independent local, regional and community media” (Verza et al., 2024).

The area of Social Inclusiveness also maps risks related to protection against disinformation and hate speech. For hate speech, the MPM evaluates the availability and effectiveness of the legal framework aimed at countering online hate speech and assesses whether efficient mechanisms for reporting online hate speech are in place. Regarding disinformation, the MPM examines whether a country has a policy or strategy to foster cooperation among different stakeholders to tackle disinformation while safeguarding freedom of expression. The analysis further looks into fact-checking initiatives to determine if they operate with high ethical and professional standards and if their funding is transparent. Independent research is crucial to understanding disinformation and the effectiveness of policy responses. Although the EU is the most advanced region globally in terms of legal and policy instruments to tackle disinformation, empirical and systematic research on disinformation remains sporadic or non-existent in most countries covered by the MPM2024.

More detailed results, including other indicators and specific-country cases are available to explore here.

Despite the increasingly complex and challenging conditions for media freedom and pluralism in recent years, systematic analyses within the Media Pluralism Monitor indicate several positive developments, primarily in terms of identifying, better defining, and addressing certain risks. For instance, after years of highlighting the potential for misuse of state advertising in media capture, this issue is now recognised and addressed by the European Media Freedom Act. Similarly, the relationship between the media and digital platforms is acknowledged and delt by several EU instruments in order to protect the media market and the democratic role of the media.

Just as the monitoring of risks to media freedom and pluralism led to the creation of EMFA, ongoing assessment will be crucial in the period leading up to and during the implementation of this EU regulation. In this context, the results of the MPM2024 provide a snapshot of the state of play one year before the EMFA is implemented across the EU.