Yael de Haan, University of Applied Sciences Utrecht/University of Groningen

Context

There is a rich variety of local media outlets in the Netherlands, including regional and local TV and radio broadcasters, regional and local newspapers, local weeklies and online hyperlocal sites[1]. However, over the past decade, policymakers, academics and journalistic organisations have voiced their concern about the state of local journalism. Several studies have concluded that while at first sight there are enough local and regional media that people can choose from, a closer look shows that many news organisations are struggling financially and have difficulties in providing quality journalism and reaching a diverse public.[2]

The local media landscape in the Netherlands is geographically focused. There is little attention paid to specific community media. However, historically local public broadcasters started as community media. While local public broadcasters clearly focused on specific local regions, their goal was and is to connect citizens and for citizens to participate in making stories from within society. Currently, there is no policy specifically facilitating community media.

The debate on the state of local journalism is not an easy one and concerns a difficult interplay between local news media, regional news organisations and (local) government. Three issues are at stake:

The main challenge is that the available budget for local journalism is not sufficient to fulfil journalistic functions and to produce professional productions. In recent years, the national government has increased funding for local journalism and investigative journalism. A recent study shows that most of the local public broadcasters, the local weeklies and the hyperlocal organisations hardly have the infrastructure, organisation and professional routines to do investigative journalism. First and foremost is the issue of professionalisation of local newsrooms and the transition to a digital newsroom[3].

Second, the funding for local public broadcasters will increase in the coming years, but the national government also wants to shift the responsibility of the yearly funding from local to national government so that local media can operate independently from local governments. However, the latter believe this is not beneficial for the collaboration between local governments and local public broadcasters.

Third, while the funding for local public broadcasting is increasing, local private media feel deprived as the funding is now focused on public local broadcasters, failing to stimulate a balanced local media landscape[4].

Lastly, the question is what is local and what is regional? What are the geographical boundaries of specific media and how can local and regional media collaborate?

Concluding, in the Netherlands there is a concern about news deserts, relating to the number of outlets and even more so, to the quality of local news and the professionalisation of newsrooms. While the funding for local journalism has increased, this leads to conflicting interests.

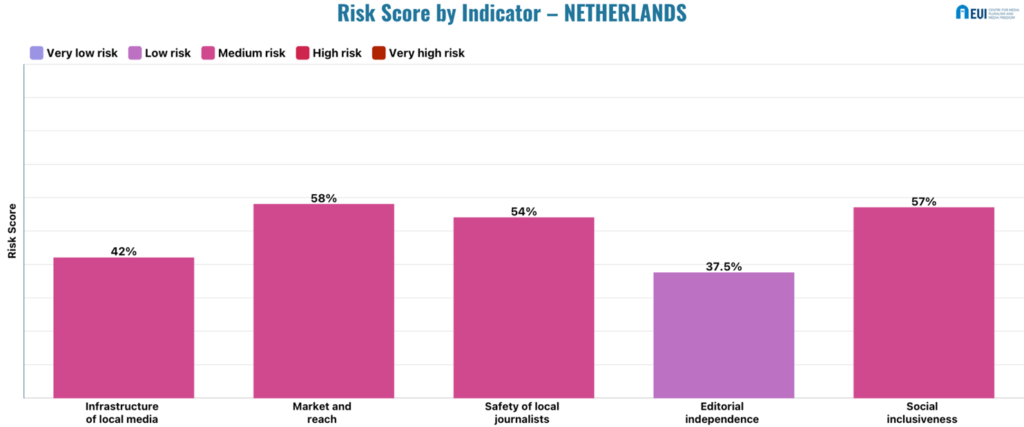

Below, different aspects of the local media landscape are discussed with risk indicators visualised in the bar chart.

[1] Hyperlocals are defined as online media that cover the news of a specific municipality. They are stand-alone websites, not linked to local newspapers or local broadcasters. See M.C. Negreira-Rey, Y. De Haan, R. van den Broek (2023), Boundaries of Hyperlocal Journalism: Geographical Borders, Roles and Relationships with the Audience in Spain and the Netherlands. In Blurring Boundaries of Journalism in Digital Media: New Actors, Models and Practices, pp. 81-88. Springer Nature.

[2] P. Bakker & Q. Kik, “Op het tweede gezicht: regionale en lokale media en journalistiek 2000-2017, 2018” https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/blg-846876.pdf,

[3] Ministerie OCW, Visiebrief Lokale Omroepen, 2023, https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-c189161df82bdae4dc36fceae1feaef6814e427d/pdf

[4] Villamedia, “Kabinet slaat plank mis bij versterking van lokale en regionale journalistiek”, 2023, https://www.villamedia.nl/artikel/kabinet-slaat-plank-mis-bij-versterking-van-regionale-en-lokale-journalistiek

Main findings

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (42%)

The Netherlands comprises 342 different municipalities. Over a period of ten years, there has been a shift in the presence of local media on the ground. Especially for the press, there has been a decrease in the average number of titles: from 1.8 to 1.4 print local news outlets per municipality. In contrast, there has been an increase in local public broadcasters and hyperlocal services. It should be noted, however, that despite a significant decrease in the number of municipalities, there is a stabilisation with an average of 5.9 local media per municipality in 2012, 2015, and 2020[1].

The number of local media outlets differs per region, and this is not always related to rural or suburban areas. In some suburban areas, such as in the north of Friesland province, each municipality has on average 10 media outlets. These include a regional broadcaster, regional newspapers, local weeklies, local hyperlocal services and local public broadcasters. However, in other regions such as Flevoland province, parts of Zeeland and parts of Limburg the number of outlets is scarce. While there are differences between provinces, studies show that citizens residing in a place with fewer than 50,000 residents are exposed to significantly less local news compared to residents of places with more than 50,000 people. Research of 2019 shows that in large municipalities, there is an average of four times as much local political news compared to small municipalities[2].

Regional newspapers and broadcasters have difficulties in reaching all the regions. The regional media excel in covering the city in which they have their editorial offices. Due to budget cuts, they sometimes have difficulties dedicating attention to the surrounding areas. In small municipalities, local media would ideally take over, but they are not always capable of doing so, due to incapacity and insufficient professionals within the organisation.

The local media market is quite turbulent. While hyperlocal services have entered the market in the past ten years, many paper weeklies are closing due to financial problems or are no longer distributed adequately to people’s homes. This means that the elderly who prefer news on paper are not always reached by online hyperlocal services. Also, hyperlocal services do not provide sufficient quality journalism: in 2020, the Netherlands counted 593;[3] they come in diverse models, ranging from fully staffed operations to home-operated websites; editorial and economic foci differ substantially; yet, offering local content is not the biggest problem, many sites underperform in terms of organisation and revenues[4].

Concluding, local news in the Netherlands is offered by a variety of public and private media outlets. In addition, national newspapers, the national public service broadcaster and the national press agency are increasingly investing in regional topics and allocating regional correspondents in different parts of the country[5]. However, the overall quality of local news and the reach remains challenging.

The map you can find at the following link refers to the number of local and regional media in the Netherlands in 2020. The original data source for this visualisation is Lokale journalistiek in Nederland – Rijk van den Broek en Yael de Haan and you can access it here.

[1] Lectoraat Kwaliteitsjournalistiek in Digitale Transitie, De opmars van de hyperlocal, 2021, https://www.journalismlab.nl/de-opmars-van-de-hyperlocal/

[2] Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek, “Nieuwsvoorziening in de regio”, 2014, https://www.svdj.nl/onderzoek/nieuwsvoorziening-in-de-regio-2014/

Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek, “Pas op! Breekbaar. Een onderzoek naar de lokale nieuwsvoorziening in de G4”, SVDJ, Netherlands, 2019, https://www.svdj.nl/onderzoek/pas-op-breekbaar/

[3] Lectoraat Kwaliteitsjournalistiek in Digitale Transitie, “De opmars van de hyperlocal”, Journalism Lab, Netherlands, 2021, https://www.journalismlab.nl/de-opmars-van-de-hyperlocal/

[4] M. Van Kerkhoven and P. Bakker, “The hyperlocal in practice”, Taylor & Francis Online, 2014, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2014.900236

[5] NPO, Concessiebeleidsplan 2022-2026: Van waarde voor iedereen, 2022, https://over.npo.nl/organisatie/openbare-documenten/concessiebeleidsplan

De Volkskrant, “Colofon,” n.d., https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/het-colofon-van-de-volkskrant~bce3473d/

Trouw, “Journalisten weten de provinciehuizen nu wel te vinden,” 2023, https://www.trouw.nl/cultuur-media/journalisten-weten-de-provinciehuizen-nu-wel-te-vinden~b2bef2c1/

Market and reach – Medium risk (58%)

While the local media landscape in the Netherlands is quite diverse, there are also financial struggles[1]. Particularly, the free printed local weeklies are facing severe problems due to decreasing advertising revenues because many local entrepreneurs have their own websites and use their own social media to advertise. Moreover, while municipalities typically advertise in private print media outlets to inform the public of local government issues, nowadays, an increasing number of them have their own websites and professional communication departments to inform the public directly. While these weeklies are struggling, they do still have the largest reach in local journalism[2].

There are currently 16 regional newspapers, owned by three publishers (Mediahuis, DPG, and BDU). The latter two own most of the newspapers in the Netherlands.[3] Regional newspapers have been struggling with declining circulation for years. In response, publishers have initiated a process of consolidation and scaling up. In this way, advertisers can potentially reach a larger market.

The local and regional public broadcasters receive yearly funding. Governmental financial support has increased over recent years, accentuating the need for a more vibrant local media landscape, by investing in local investigative journalism and the professionalisation of local public broadcasters. Historically, local public broadcasters have been financially supported through a fixed budget per household (currently 1.53 euro) and additional support by local governments. However, this has proved to be problematic for two reasons. First, areas with a sparse population receive insufficient fixed budgets to run a healthy newsroom. Second, local public broadcasters are dependent on the local government for additional financial support. There will, thus, be a shift in the financial structure from 2025 onwards from local to national government[4].

Over the past five years, increasing attention has been given to financial support for local journalism. While in 2018 the attention predominantly went to investigative journalism at a local level, it was clear that the basic local journalistic infrastructure was insufficient. Therefore, there is now financial support for the professionalisation of local public service broadcasters. However, studies analysing the level of professionalisation in local print media show there is also a need for financial support in the private local media sector. While local private media can apply for funding for specific programs related to investigative journalism and innovation in journalism from the Dutch Fund for Journalism, there is a need to facilitate the more basic processes of professionalisation and digitalisation of these newsrooms[5]. The entire local media sector, including private outlets, received financial support during the Covid-19 pandemic because of decreasing advertising revenues[6].

A recent study shows that Dutch citizens, in general, show interest in local news. 46 percent state that they are extremely or very interested in what is happening in their municipality and local government, while another 43 percent are somewhat interested. Only a very small portion of citizens indicate no interest at all (2 percent) or not much interest (9 percent)[7].

Less engaged or interested citizens prefer news from their immediate surroundings, such as their neighbourhood or district they live in. More interested individuals are also interested in the entire municipality and surrounding municipalities.

The willingness to pay for local news is low. 90 percent of all citizens state that they are not willing to pay for online news about their municipality. Among those who are highly interested, the willingness to pay is slightly higher. However, even in this group, 85 percent have no intention of paying. Citizens who prefer a paid print newspaper as their information medium for local government news are significantly more likely to be willing to pay for information about the municipality compared to those who prefer a free print newspaper[8].

Concluding, while people are very interested in local news, they are unwilling to pay for news. They prefer to look for free outlets, such as regional and public broadcasters, online channels, and not regional and local newspapers they need to pay for.

[1] We could not have access to financial information per news organisation. This is based on interviews of publishers of local print media and documents such as annual reports.

[2] Commissariaat van de Media, De staat van de lokale nieuws- en informatievoorziening: de burgerperspectief, (2022), https://www.cvdm.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Rapport-De-staat-van-de-lokale-informatievoorziening-2022.pdf

[3] Villamedia, “Hoe de Nederlandse media in Belgische handen kwamen: een overzicht”, (2022), https://www.villamedia.nl/artikel/hoe-de-nederlandse-media-in-belgische-handen-kwamen-een-overzicht

[4] Ministerie OCW, Visiebrief Lokale Omroepen, (2023), https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-c189161df82bdae4dc36fceae1feaef6814e427d/pdf

[5] Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek, “Professionalisering lokale publieke media instellingen,” n.d., https://www.svdj.nl/regeling/lokaleomroepen/

[6] Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek, “Tijdelijke steunfonds lokale informatievoorziening,” n.d., https://www.svdj.nl/regeling/steunfonds/

[7] Commissariaat van de Media, “De staat van de lokale nieuws- en informatievoorziening: de burgerperspectief”, 2022, https://www.cvdm.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Rapport-De-staat-van-de-lokale-informatievoorziening-2022.pdf

[8] Ibid.

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (54%)

The issue of underpayment is a significant problem for local journalists. While regional journalists often receive at least the minimum wage, that cannot be said for their local counterparts. Consequently, local journalism is frequently pursued as a profession only after retirement, when individuals have achieved sufficient financial stability to afford a poorly compensated position at a local news outlet, or by young journalists who want to gain experience. Some local journalists work part-time for media organisations while also holding other positions, which could raise concerns about their independence. As few staff members are employed at local media outlets, local media (both private and public) have difficulties professionalising, let alone adapting to a changing online media landscape. Nevertheless, umbrella organisations such the Association for Local Public Broadcasting (NLPO) and the association for Local News Media (NNP) facilitate local organisations in their professionalisation strategies and help them to ensure independence.

The Journalist Union has proposed a minimum wage of 30 euros per hour for freelancers starting their careers. However, experienced freelance local journalists often earn significantly less. This situation raises concerns about their independence, as many freelancers cannot solely rely on their journalistic work to make a living and must take on other professional positions. Freelancers lack social security coverage, leaving them without pay when they fall ill, whether for short or long periods. While freelancers can choose to enrol in disability or unemployment insurance, these options are often expensive, especially considering the already low pay in the profession.

Many (local) journalists are not only dealing with issues of low pay; the number of reported incidents of harassment has increased in recent years. According to the Dutch Foundation for Press Safety in 2021, 272 alerts were documented, compared to 121 in 2020. This upward trend could suggest a rise in physical assaults and harassment incidents targeting journalists. Local journalists face an even greater risk of being targeted with attacks and (online) harassment. Journalists residing in small communities are especially susceptible to being identified[1].

The PersVeilig (press safety) Foundation urges the Dutch authorities to implement a systematic and coordinated mechanism to monitor SLAPPS. Journalists in the Netherlands are becoming more cautious about publishing to avoid the risk of legal action, according to a survey conducted by PersVeilig, which was completed by 858 journalists. A quarter of the respondents stated that they adopt this approach to mitigate risks. Half of all the journalists have experienced at least one instance of legal threats following a publication, and in 20 percent of cases, this escalated to a legal complaint or prosecution. However, specific information about local journalists is lacking[2].

[1] Free Press Unlimited, “Towards a safer haven: advancing safety of journalists amidst rising threats in the Netherlands”, 2022, https://www.freepressunlimited.org/sites/default/files/documents/MFRR%20Report%20-%20Safety%20of%20journalists%20in%20the%20Netherlands.pdf

[2] NVJ, “198 incidenten gemeld bij PersVeilig in 2022,” 2023, https://www.nvj.nl/nieuws/198-incidenten-gemeld-persveilig-2022

Editorial independence – Low risk (37.5%)

The main aim of the Dutch Media Act 2008 is to provide a varied range of radio and television channels, which everyone can receive. The Act sets requirements for both public and private broadcasters. In the Dutch Media Act there is no explicit article preventing ownership control of commercial or privately owned media, but it does contain some norms and rules concerning the appointment of the board. Private, publicly listed, local media companies must adhere to the Code of Good Governance in which no conflict of interest is required. The ownership structures of relevant commercial publishers in the local sphere, such as Mediahuis, DPG, BDU are not explicitly controlled. Still, there is a low risk detected in this specific subdomain of private media.

No significant concerns are detected when it comes to the criteria and distribution of state subsidies to local media outlets. The programs are organised by the Dutch Journalism Fund, which receives a yearly budget from the Ministry of Media. All the procedures are open and transparent. While the Dutch Journalism Fund has predominantly channelled funding for public local media outlets, since the Covid pandemic, it has also provided subsidies to help private local media outlets financially. Currently, specific programs to help local print outlets to innovate to the online environment are in place. Not least, the programs for investigative journalism at a local level, which stimulate collaboration between news organisations, both public and private.

State advertising in local media has a long history of local governments publishing in printed local free weeklies about local government information and permit applications that citizens have received. As of 2022, a new law has been installed in which all permit applications need to be also published online. The purpose of this legislative change is to fully inform society digitally about decisions that have an impact on the living environment. Citizens are informed by the government about these decisions so that they can exercise their right to participate in a timely manner.

In terms of protection from commercial and political influences over editorial content, both public and private media are obliged to have an editorial statute guaranteeing editorial independence. However, at a local level, the editorial statute is not required but only encouraged. While local umbrella organisations such as the Local Public Broadcasting Association (NLPO), and local publishers such as NNP, stimulate and facilitate local media to install editorial statutes, in practice, there is great variety among local media organisations.

The Dutch Media Authority, the independent regulator for audiovisual media, is responsible for conducting research on the diversity and independence of information provision in the Netherlands and advises the Minister of Primary and Secondary Education and Media. It has a remit over local public media[1]. The process to apply for a local public broadcasting licence is written in the Media Act and conducted by the Media Authority. This is done accordingly in a fair and transparent way.

In terms of independence of national and regional public broadcasters, the Media Act explicitly specifies incompatible functions concerning membership of the supervisory board and the board of directors[2]. This is not the case for local public broadcasters. However, as of 1 July 2021, the Law on Governance and Oversight of Legal Entities (WBTR in Dutch)[3] is in effect in the context of good governance.[4]Local public broadcasters must adhere to this. The Dutch Media Act also ensures independent journalism by stipulating that public media services must provide media content that is independent of commercial influences and free from government influences. In this specific subdomain, a medium risk is observed mostly because local PSB are still dependent on municipality funds. However, in the coming years, funding for local PSB will shift from local to national government.

Some concerns are detected concerning editorial independence of local media. First, due to financial pressures, many local media are dealing with budget cuts, and have difficulties in providing only independent journalism. Second, political influence over local editorials can happen indirectly, since local governments have control over the budget of local PSB, and the fact that local media in general are not bound by editorial statutes. Moreover, the increasing influence of communication departments at local governments, which often use journalistic newsroom conventions, makes the distinction between journalism and communication unclear. This is a great concern among journalists. Third, the fees for local journalists are not sufficient, meaning (freelance) local journalists are obliged to take on commercial jobs or tasks, possibly interfering with their independent role.

Overall, the editorial independence of local media does not show high risks, while there are some concerns to take into account.

[1] Commissariaat van de Media, n.d., https://www.cvdm.nl/

[2] Mediawet 2008, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0025028/2023-01-01

[3] Wet Bestuur en Toezichtspersoon, 2021, https://wbtr.nl/de-wet/

[4] This amendment to the Civil Code aims to enhance the governance of foundations (and associations), incorporating rules on tasks, powers, obligations, and liability.

Social inclusiveness – Medium Risk (57%)

News in the Netherlands is traditionally not aimed at reaching minorities and most news organisations do not provide news in different languages. However, with the increasing number of immigrants in the Netherlands, in 2015 the Dutch Public Broadcaster NPO created the platform Net in Nederland (New to the Netherlands)[1]. The platform provides information in Dutch and Arabic about Dutch history, culture and language and is specially made for and by immigrants. However, this does not resolve the language gap, an issue that became quite prominent during the Covid pandemic, when many minorities were unable to read crucial news on policy measures. This also became clear during the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria in 2023. Acknowledging the issue of the language gap, in 2022, the Dutch Public Broadcaster started to experiment with the automatic translation of news articles by means of artificial intelligence. News articles can be translated into English, Turkish, Polish, Arabic and Chinese[2]. Regional broadcasters are also experimenting with artificial intelligence to translate news into different languages.

Nevertheless, outlets in different languages do not solve the issue of the representation of minorities in the news. Many studies show that minorities are negatively represented or under-represented in news reporting and television programs of the Dutch public service media[3]. In studies conducted with the immigrant audience, many participants also perceive Dutch media reporting as judgmental and portraying a negative image of immigrants[4]. They do not recognize themselves in Dutch public media reporting.

There are private news outlets that distribute news services in minority languages. Due to the emergence of the Internet and social media, there are several private (online) outlets that aim to reach non-Dutch immigrants and provide news in the English language. Increasingly, specific groups are starting their own online communities to share news on what is going on in the Netherlands, translating news into specific languages tailored to a specific group, such as the Brazilian or Polish community. These are online communities that start from the community itself and are often not journalistic platforms. However, no systematic research has been conducted on these platforms.

[1] NPO, “Net in Nederland,” n.d., https://npokennis.nl/program/13/net-in-nederland, .

[2] NOS, “About NOS Lab,” n.d., https://translations.lab.nos.nl/about

[3] Kartosen-Wong, “Diversiteit is bij de NPO eerder wensdenken en pr-praat dan werkelijkheid,” 2020, https://www.parool.nl/columns-opinie/diversiteit-is-bij-de-npo-eerder-wensdenken-en-pr-praat-dan-werkelijkheid~b8aadb45/?referrer=https://www.google.com/, ; J. Engelbert and I. Awad, “Securitizing cultural diversity: Dutch public broadcasting in post-multicultural and de-pillarized times,” 2014, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1742766514552352

[4] A. Alancar and M. Deuze, “News for assimilation or integration? Examining the functions of news in shaping acculturation experiences of immigrants in the Netherlands and Spain,” 2017, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0267323117689993

Best practices and open public sphere

The Dutch Fund for Journalism[1] encourages and facilitates funding for innovative projects in local journalism. The initiatives are diverse and range from stimulating interaction between local media and the public, to working on collaboration between investigative journalists’ collectives, local media and citizens and to creating more community journalism at neighbourhood level in large cities. In coming years, the Fund will not only facilitate financially but also help local news organisations through coaching and courses.

Stimulated by national media policy, in 2021, a project was launched to enhance the collaboration between public broadcasters at the national, regional and local level. The objective is twofold: to facilitate professionalisation and to create more synergy between local and national news. While this specific project ended in 2023, collaboration at three levels has been stimulated and is still one of the focus points in media policy[2].

Public broadcasters are increasingly seeing the added value of collaboration, not only for specific media coverage, but also for facilitating community building in a specific region. For example, in December 2023, the regional broadcaster Omroep West[3] collaborated with ten local public service broadcasters in the same region to start a fundraising campaign during the holidays for families with limited financial means. Similarly, the regional public service broadcaster NH Nieuws[4] started an initiative to connect people seeking assistance with those willing to offer help. These projects show that journalists do not only take on the role of informer but also of facilitator in connecting people with each other.

[1] The Dutch Fund for Journalism, “Supported projects,” 2023, https://www.svdj.nl/projecten/, .

[2] Ministerie OCW, “Visiebrief lokale omroepen,” 2023, https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-c189161df82bdae4dc36fceae1feaef6814e427d/pdf

[3] Omroep West, “Van de Hoofdredactie: hoe Sinterklaas drilboor doet zwijgen,” 2023, https://www.omroepwest.nl/nieuws/4777898/van-de-hoofdredactie-hoe-sinterklaas-drilboor-doet-zwijgen

[4] NH Helpt, NH Nieuws, 2023, https://jouw.nhnieuws.nl/

Map of Local and Regional Media in the Netherlands

This map shows the number of local and regional media in the Netherlands in 2020. You have the option to filter by media format, municipality and province. Hover over a municipality to view the number of media outlets, giving a breakdown by format. Clicking on a specific municipality provides a detailed list of media outlets in the table below the map, complete with information on format and ownership details. The original data source for this visualization is Lokale journalistiek in Nederland – Rijk van den Broek en Yael de Haan, and can be accessed by clicking here.