Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Malta

Louiselle Vassallo, Department of Media and Communications, Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta

Context

Malta is a Mediterranean island state and one of the smallest archipelagos in the world, with a total land area of 320 square kilometres[1] and a population of 531,113.[2] Only the 3 largest islands (Malta, Gozo and Comino) are inhabited, and It is the most densely populated EU member state, with an estimated 1,620 persons per square kilometre.[3]

In view of its geographical size and an oversaturated media landscape, there is no debate on local “news deserts” in Malta. It is a given that what are considered to be national media outlets are also local, since all the territory is reached by the news media. Additionally, what is “local” becomes national, since newsworthy content across the territory is covered on a national level by the leading news outlets for all media formats (press, TV, radio, online). Community radio stations are normally village or town based and serve to cover cultural aspects like religious village feasts or specific locality based events.

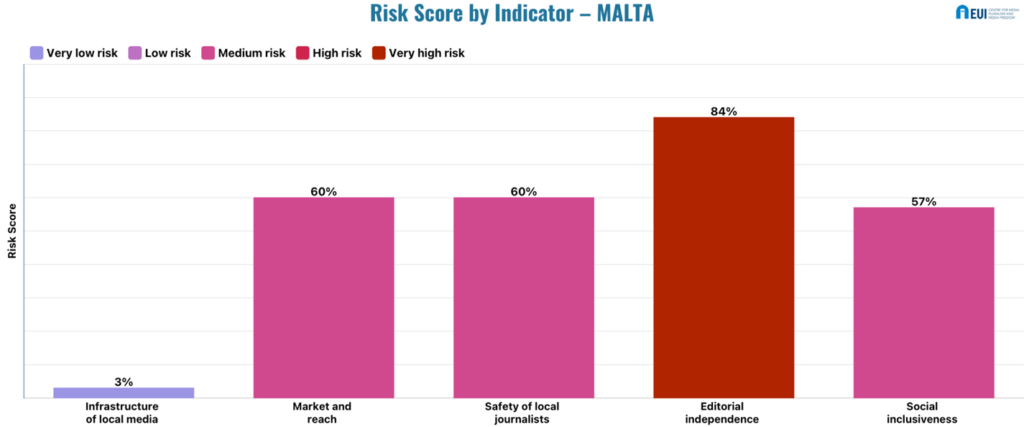

The most serious issue, as highlighted by the graph below, is the lack of editorial independence of a number of media outlets in Malta: the two main political parties in Malta own and operate multimedia outlets. In contrast, the variable granularity of the infrastructure of local media carries a very low risk, since the national media, as mentioned above, fulfil the obligations that, in a larger country, would be addressed by local or community media outlets.

[1] World Bank Data, Surface Area (sq. km.) Malta, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.SRF.TOTL.K2?locations=MT.

[2] World Bank Data, Malta Overview, 2022, https://data.worldbank.org/country/malta?view=chart.

[3] World Bank Data, Population density (people per sq. km of land area) – Malta, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST?locations=MT.

Main findings

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Very low risk (3%)

In Malta, local media are not defined in law, and there has been no development of “local media” as a concept, since the whole country is covered by national outlets, through all media formats. For the purposes of this research, the national media are to be understood as “local” as well, since they are one and the same in view of Malta’s geographical size. There is, thus, no distinction made between local and national media in Malta. There are no “local” editions of the national media, and whilst Malta has a few community radio stations, regional media does not feature in the Maltese media landscape. This is also in view of the fact that all the territory is easily accessible to the news media, and the “local” is what makes up “national” news, and is covered by all leading outlets, including PSM:[1] TVM, TVMNews+, TVMSports+, Radju Malta 1 and 2 and Magic Malta, all operated by Public Broadcasting Services (PBS)[2] Limited, which is owned by the Government of Malta.

All media are available over the entire territory and communities in suburban areas in Malta are well served by the national media (TV, radio, print and online). Essentially, data pertaining to consumption on a national level apply, as confirmed by the Malta Communications Authority Annual Report, 2022, which states that 94% of the respondents expressed satisfaction with their experience when using internet and TV services.[3] Additionally, with the advent of digital radio (DAB), previously problematic pockets of reception, where the radio signal was unavailable or of inadequate quality, have been reached, including all the islands of the Maltese archipelago.

Community media, on the other hand, are defined only as pertaining to radio: the “community radio service” is designed to cater for the needs of a particular community or locality and has a limited range of reception.[4] These radio stations are normally village or town based and serve to cover cultural aspects like village religious feasts or specific locality based events. There are currently 20 community radio stations listed on the Broadcasting Authority’s website, the majority of which are run by religious (Catholic) organisations. In the online sphere, the African Media Association Malta is an online community radio, web magazine, which also publishes video clips and podcasts. There are no community TV stations or print media publications, except ad hoc publications issued by local councils, or organisations like parish councils.

[1] TVMNews,Landing page, https://tvmnews.mt/

[2] Registry of Companies, Public Broadcasting Services Limited – Involved Parties, 2024, https://registry.mbr.mt/ROC/index.jsp#/ROC/companyDetailsRO.do?action=involvementList&companyId=C%2013140.

[3] Malta Communications Authority, Annual Report and Financial Statements 2022, 2023, https://www.mca.org.mt/sites/default/files/MCA Annual Report 2022.pdf.

[4] Broadcasting Act, 2020, https://legislation.mt/eli/cap/350/eng/pdf.

Market and reach – Medium risk (60%)

Anecdotally, most media outlets (national) report that they are struggling economically, however there is no data to refer to since financial information pertaining to media outlets, including revenue data, is not publicly available. The fact that there are no publicly available figures to compare, and that the financial stability of the media sector has not been monitored over a period of time, should be considered high risk, since there is no way of determining the level at which assistance is required and, thus, no policy is being designed to assist media outlets that need support. The only platforms that disclose their financial situation are The Shift News—which does not accept government funding; accepts direct advertising from reputable business entities; and also relies on crowdfunding and NGO grants—and blogger Manuel Delia, who has no affiliation to any organisation and no corporate or public funding, and operates by accepting donations and offering subscriptions.

The Broadcasting Authority, the Malta Communication Authority and the Malta Competition and Consumer Affairs Authority do not publish economic data for the media sector, and company accounts are not available publicly. The only source that may be referenced is WARC data, which show that, when it comes to radio revenue, there has been an increase from 3 million euro in 2021 to 3.2 million euro in 2022 in radio advertising expenditure; when taken into the context of GDP growth vis-à-vis the inflation rate, this was evaluated as stationary.[1]Furthermore, according to Statista[2], the revenue for the digital market in Malta in the coming years “is expected to soar.” However, unless financial data pertaining to the entire media market, as well as broken down according to separate media formats, are made public, there are no numbers or trends on which policy and potential assistance can be based.

Currently, there is no scheme that provides financial support to community media. These operate through volunteers and have an extremely limited reach, generally covering the territory of the village concerned.

If one rules out PSM, which are funded by the state, it is safe to say that the government does not provide enough financial support for media outlets, as there are no regular economic schemes designed to strengthen the media industry, bar a couple of initiatives: in view of the substantial increase in the price of paper and following lobbying by some news outlets a one-off, ad hoc grant[3] of €500,000 was launched in 2022 and distributed amongst local print media; and a 2023 Arts Council Newspapers Support Scheme[4], totalling €400,000, aimed at promoting good use of the Maltese language and Maltese culture in newspapers. Only Maltese language newspapers are eligible. One cannot fail to note that 4 of the beneficiaries of the latter (2 dailies and 2 weeklies) are owned by the two main political parties (Partit Laburista (PL), in government, and the Partit Nazzjonalista (PN), in opposition), whilst the editorial line of the 3 remaining Maltese language newspapers is openly sympathetic towards the PL. Essentially, this scheme excludes all the independent print media, who publish in English. No similar funds have been announced for digital media or other modern variants in journalism.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the government was also criticised for not distributing funds equally, with reports that political party media got the lion’s share of the financial assistance offered. It was also not clear as to whether independent newsrooms had to agree to certain terms in order to receive funds, as reported by the International Press Institute.[5]

The only other route through which the Maltese government “supports” local media is direct advertising booked by ministries or state entities, however, allocation of this type of “funding” is not transparent, and there is no control or checks and balances to monitor fair distribution amongst outlets. This means that the state can choose to favour some media outlets over others, as was exposed in January 2022, when 18 ministers and parliamentary secretaries paid €16,700 worth of public funds for ads in a single edition of the Partit Laburista’s Sunday newspaper Kullħadd.[6]

This lack of transparency has led NGO Repubblika to propose guidelines for public advertising.[7] The NGO reports that “expenditure in the media, particularly print media, on a discretionary and discriminatory basis is rampant.” This was further highlighted by The Shift News in an investigative piece about how the government favours advertising agencies with close links to the party in government with direct orders.[8]

[1] L. Vassallo, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Malta, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, Country Report – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/75731.

[2] Statista, Market Insights: Digital Media – Malta, 2023, https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-media/malta

[3] M. Vella, Newspapers to get €500,000 fund as Ukraine war pushes up price of paper. MaltaToday, 2022, https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/116885/newspapers_to_get_500000_fund_as_ukraine_war_pushes_up_price_of_paper.

[4] Arts Council Malta, Newspapers Support Scheme, 2023, https://artscouncilmalta.gov.mt/pages/funds-opportunities/opportunities/newspapers-support-scheme/.

[5] International Press Institute, COVID-19 adds to press freedom challenges in Malta, 2020, https://ipi.media/covid-19-funds-threaten-media-independence-in-malta/.

[6] T. Diacono, 18 Ministers Paid Labour €16,700 In Public Funds To Run Ads In A Single Newspaper Edition, 2022, https://lovinmalta.com/news/18-ministers-paid-labour-e16700-in-public-funds-to-run-ads-in-a-single-newspaper-edition/.

[7] Repubblika, Draft guidelines on information and advertising campaigns by government, 2021, https://repubblika.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Draft-guidelines-on-public-advertising.pdf.

[8] E. De Gaetano, Propaganda propping up a party. The Shift News, 2023, https://theshiftnews.com/2023/04/10/propaganda-propping-up-a-party/.

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (60%)

Malta is small, so all locations are within reach of all journalists. Where they are based has no consequence on access and they operate from all areas within the territory. There are no news agencies in Malta, only national news outlets.

When it comes to employment, and still considering the national media as local, the overall observation is that there is a slight increase in the number of journalists in employment, mainly because of the launch of new digital native news outlets. In contrast, though, the president of the Institute of Maltese Journalists (IĠM) has confirmed that, overall, working conditions for journalists have worsened since spending budgets by media outlets have decreased, leading to the refusal of any employee requests for a salary increase.[1] The consequences of this scenario are even more serious, when taken in the context of an ever-increasing cost of living.

In relation to the role of journalists’ organisations, the Institute of Maltese Journalists does not (and cannot, in practice) ensure professional standards and editorial independence. They have guidelines, but these are not binding. Additionally, they had committed to updating their code of ethics some 2-3 years ago, but to date this has not happened.

When it comes to SLAPPs, a 2023 analysis by the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE)[2] shows that, in 2022, Malta had the highest number of SLAPPs per capita in Europe, with 19.93 cases per 100,000 people. The data included multiple cases brought by a number of ministries and state agencies against the online investigative portal The Shift News, in relation to 40 Freedom of Information requests that had been denied. The gravity of the staggering number of cases faced by the Shift News is further highlighted by the case of the journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, assassinated in 2017, who faced 43 civil and five criminal lawsuits at the time of her assassination.[3] Malta’s SLAPP score is even more significant when compared to Europe’s second-most SLAPPed country, Slovenia, which had just 2.02 SLAPPs per 100,000 citizens in 2022. Harassment of journalists and media entities, as reported by the ECMPF’s Mapping Media Freedom, also include: a large-scale disinformation campaign[4] targeting six independent media outlets and a news blogger, through the creation of spoof websites and the sending of fake emails to newsrooms, with the primary objective of spreading false facts; DDoS attacks from unknown actors; legal threats by members of the business community; and consistent denials of FOI requests made by newsrooms to the state and its entities.

[1] M. Xuereb, President of the Institute of Maltese Journalists (IĠM), 21 February 2023, Personal correspondence.

[2] Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe, SLAPPs: Increasingly Threatening Democracy in Europe, 2023, https://www.the-case.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/20230703-CASE-UPDATE-REPORT-2023-1.pdf.

[3] J. Balzan, Malta with highest number of SLAPPs per capita in Europe, Newsbook, 2023, https://newsbook.com.mt/en/malta-with-highest-number-of-slapps-in-europe/.

[4] ECMPF, Mapping Media Freedom – Monitoring Report 2021, 2021, https://www.ecpmf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/MFRR-Monitoring-Report.pdf.

Editorial independence – Very high risk (84%)

In Malta, political parties can legally own and operate media outlets. Both the two largest parties in Malta, the PL, currently in government, and the PN, in opposition, own and operate TV and radio stations, online news media formats and publish daily and weekly newspapers. This is problematic not only in terms of political control, but also because commercial entities have a strong influence on both the PL and the PN, in view of weak party financing regulations, resulting in both direct and indirect pressure on newsrooms.

In 2021, the Lovin Malta newsroom, a commercial, news and entertainment online site, gave notice that it was going “to start constitutional proceedings against the party-owned stations, arguing that a section of the Broadcasting Act concerning political party stations breaches the spirit of the constitution and must be declared null and void.”[1] The case is still ongoing, and no developments have been registered.

As outlined in the previous section, the government and its entities are a primary source of advertising income for all media outlets, which is an added risk to editorial independence. The state can use this as leverage to put pressure on newsrooms to report sympathetically on government affairs. Moreover, concerns are also detected when it comes to state subsidies, both in terms of fairness and transparency.

There is no self-regulation structure or mechanism in place. The Institute of Maltese Journalists (IĠM) is an association and does not operate as a union. Moreover, “the Institute of Maltese Journalists has yet to find ways of enforcing its code of ethics or update it.”[2]. The IĠM’s intention is to develop into a self-regulatory structure, but this has seen little progress, mainly in view of the fact that all members on the IĠM board are volunteers, who are also full-time journalists, and struggle to put in enough hours to the running of the Institute.

The main characteristics attributed to the Maltese media landscape include “the dependence of the media on the state and major institutions, the tendency to favour advocacy journalism, lack of journalistic autonomy, a high level of political instrumentalization of the media, limited journalistic professionalism and a politicised public service broadcaster.”[3] As outlined by Reporters Without Borders (RSF)[4], “the ruling party wields a strong influence over the public broadcaster and uses public advertising to exert pressure on private media.” Furthermore, RSF highlights how politicians favour specific journalists, for exclusive interviews, over others, who are considered “hostile” and are, consequently, ignored, as well as the fact that the government issues an “access card”[5] to journalists, also referred to as a Press Card, which gives the latter access to covering government events or press conferences. Some journalists refuse to subscribe to this system, arguing that it should not be up to the state to decide who is a journalist or not. However, these individuals are, in turn, not informed or invited to government press conferences, and instead have to rely on colleagues to let them know when such events are taking place. Assassinated journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia wrote about this system, describing it as an undemocratic and “offensive practice”.[6]

The long overdue media reform law, which is to protect journalists and the journalistic profession, amongst other things, is yet to be proposed, following a draft that had to be retracted.[7] Since then, all progress on the reform seems to have stalled completely.[8]

The only dedicated media authority in Malta is the Broadcasting Authority (BA) which, as the name suggests, covers TV and radio formats. More recently, the Broadcasting Act was amended to include aspects of audio-visual content carried by online news outlets. The board of the BA is composed of 5 appointees, all nominated by the two main political parties, and excludes the participation of all other stakeholders, meaning that the political parties, essentially, regulate themselves. Added to this, the BA tends to focus primarily on PSM, with the view that political party-owned TV and radio stations balance each other out in the polarised content they broadcast, instead of applying the rules of objectivity and impartiality independently and equally to both entities. This stance was highlighted in the Daphne Caruana Galizia Inquiry report[9], and described as a misinterpretation of the concept of impartiality.

[1] I. Martin, Court could decide on the future of ONE, NET, Times of Malta, 2021, https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/court-could-decide-on-the-future-of-one-net.843840.

[2] N. Vella, J. Borg and M. A. Lauri, Ibid.

[3] N. Vella, J. Borg and M. A. Lauri, Malta’s Media System from the Perspective of Journalists and Editors in Journalism Practice, 2023,DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2023.2199719.

[4] Reporters Without Borders, RSF Malta Factsheet, 2023, https://rsf.org/en/country/malta.

[5] Department of Information, Department of Information (DOI) Access Card, 2024, https://www.servizz.gov.mt/en/Pages/Other/Government-Information-Services/Media/WEB001/default.aspx.

[6] D. Caruana Galizia, On the matter of press cards issued by the Department of Information. Running Commentary, 2016, https://daphnecaruanagalizia.com/2016/01/on-the-matter-of-press-cards-issued-by-the-department-of-information/.

[7] A. Taylor, Maltese journalists up in arms over closed media reform. Euractiv, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/all/short_news/maltese-journalists-up-in-arms-over-closed-media-reform/.

[8] ECPMF, Malta: Press freedom groups urge PM to deliver strong media law reforms, 2023, https://www.ecpmf.eu/malta-press-freedom-groups-urge-pm-to-deliver-strong-media-law-reforms/.

[9]M. Mallia, J. Said Pullicino and A. Lofaro, Public Inquiry Report Daphne Caruana Galizia – a journalist assassinated on 16th October 2017 (Courtesy translation, v20211024 provided by Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation), 2021, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21114883-public-inquiry-report-en.

Social inclusiveness – Medium risk (57%)

There are no legally recognised minorities in Malta. Of course, minorities do exist in Malta and, over the last ten years, the number of third country nationals residing and working in Malta has increased exponentially. According to the latest census, more than one in five residents are foreign, with 115,449 non-Maltese persons residing in Malta, an increase of more than five times in the share of foreigners since 2011.[1] The Times of Malta[2] reports that, according to figures tabled in parliament in January 2024, as of July 2023, there were 68,755 workers in Malta from outside the EU, the largest number coming from India (13,158), followed by the Philippines (9,560), Nepal (8,157) and the United Kingdom (5,144). Countries that also have a significant number of workers in Malta include Serbia (4,106), Albania (3,418) and Colombia (3,149).

So, whilst minorities do exist in Malta, they are largely invisible or under-represented in the local media landscape. PSM broadcasts mainly in Maltese, with one short, daily news bulletin and the odd programme, possibly imported, in English, which is not a minority language, but the second official language in Malta. In a nutshell, the only languages used within the Maltese media landscape are Maltese and English, with the exception of some content to be found on the African Media Association[3] site, which includes some content in French and Arabic, even if this is limited and not updated regularly.

In reference to the Fifth Opinion on Malta,[4] Human Rights NGO Aditus highlights Malta’s stance that “there are no national minorities in Malta”, and expresses concerns about the lack of opportunities for individuals to receive information.

In essence, Malta seems to rely on the fact that all non-Maltese residents speak and understand English, and when it comes to broadcast formats, practically every station broadcasts mainly in Maltese, whilst English tends to be more dominant in print and online media. Furthermore, there is no obligation for PSM to represent minorities, specifically, in a fair and adequately representational manner and, according to the Broadcasting Authority, when it comes to the portrayal of minorities in broadcasting, there is no policy in place, except for general provisions of balanced, fair and impartial representation.[5] Ultimately, it follows that there is nothing legally binding the Broadcasting Authority to introduce regulations ensuring that minority languages are included in news content, since there is no legal framework upon which such measures can be based. Moreover, when minorities are represented, it is generally in relation to irregular immigration arrivals or deportations, or news that concerns accidents and crime.

There are no outlets or channels specifically addressing marginalised groups in Malta. This is not to say that women, members of the LGBTIQ+ community or persons with a disability are not represented. However, there is no measure available for this.

Malta, which is one of the few countries in the world to have made LGBT rights equal at a constitutional level, ranks high in LGBTQI+ civil rights, and this is also generally reflected in most media formats.

Persons with disabilities are sympathetically portrayed, even if content is often in relation to the disability itself. Malta’s 2021–2030 National Strategy on the Rights of Disabled Persons states that “accessing culture and leisure through the media require conformity with certain processes, and the inclusion of elements such as closed captioning, also in light of EU legislation binding Malta such as the European Accessibility Act and the Audio-Visual Media Services Directive. Finally, the ever-present challenge of ensuring correct, rather than tragedy-based and medicalised portrayal of disabled persons through the local media, is again brought up, with the aim of enabling disabled persons to both feel comfortable engaging in the media, and also participating in media experiences on the same basis as others.” [6] The report also includes a page about representation and captioning, however, beyond listing desired results, there is no concrete strategy as to how these will be achieved.

When it comes to accessibility, sign language is only used in broadcasts of national interest. In 2021, the PSM chairperson announced that the upcoming 2021-2022 schedule would include more sign language programmes to truly affirm inclusion,[7] on observation of current content, this does not seem to be the case.

Overall, although national media provide sufficient public interest news to meet the critical information needs of the communities they serve, and there is no real need for additional “local media” outlets, the issue remains that the media landscape is dominated by PSM and political party-owned outlets, especially when it comes to broadcast and, more specifically, TV.[8] Consequently, the editorial line of political parties dominates the narrative. A number of independent media outlets cover important stories that are of interest to the general public, as well as smaller communities that might be underrepresented, however, these are primarily online and print formats, and there is no official data that can gauge their level of engagement and reach.

[1] National Statistics Office, Census of Populations and Housing – Final Report: Volume 1, 2023, https://nso.gov.mt/wp-content/uploads/Census-of-Population-2021-volume1-final.pdf.

[2] D. Ellul, Identità increases work permit fees for non-EU workers, Times of Malta, 2024, https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/identita-increases-work-permit-fees-noneu-workers.1077309.

[3] African Media Association, Landing page, 2024, https://www.africanmediamalta.com/.

[4] Aditus, Malta and national minorities: what does the Council of Europe say?, 2021, https://aditus.org.mt/malta-and-national-minorities-what-does-the-council-of-europe-say/.

[5] Dr J. Spiteri, CEO Broadcasting Authority, 17 November 2022, Personal correspondence.

[6] Ministry for Inclusion and Social Wellbeing, Freedom to Live | Malta’s 2021 – 2030 National Strategy on the Rights of Disabled Persons Consultation Document, 2021, p. 48, https://meae.gov.mt/en/Public_Consultations/MISW/PublishingImages/Pages/Consultations/Maltas20212030NationalStrategyontheRightsofDisabledPersons/Proposed%20National%20Disability%20Strategy%20%E2%80%93%20Standard%20English%20version.pdf.

[7] A. Rossitto, PBS launches new news station, TVM News, 2021, https://tvmnews.mt/en/news/il-pbs-iniedi-stazzjon-pbs-launches-new-news-station-tvmnews-tal-ahbarijiet-tvmnews/.

[8] Fsadni & Associates, Broadcasting Authority Audience Survey – May 2023, 2023, https://www.dropbox.com/sh/9oxo9v3ohs3tov0/AAAFZGy4vXoy-ZYeQ6ppqfr3a/B.A.%20Audiences/Audience%20Assessments/2023-May?dl=0&preview=Audience+Survey+May+2023.pdf&subfolder_nav_tracking=1.

Best practices and open public sphere

Maltese civil society has not felt the need to demand the strengthening of community (or local) media, since the media landscape is already oversaturated as it is, and the need for community media is not felt. However, initiatives that are worth noting are podcasts like the one launched by interviewer Jon Mallia,[1] who conducts lengthy, one-on-one, in-depth interviews, and The SHE Word,[2] a discussion programme dedicated to women’s issues, both available on Patreon and social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram, as well as Repubblika LIVE broadcasts on Facebook. Repubblika is a Civil Society NGO, which, from time to time, organises online broadcasts in the form of discussion programmes, covering current affairs issues. Additionally, a newcomer to the blogging/in-depth reporting community is the online site the Critical Angle Project,[3] launched by freelance journalist and activist Julian Delia, and which includes a highly visual and detailed timeline, presented as a repository of public domain information about Malta’s most significant corruption scandals over the past decade.

Some news outlets, like Newsbook, have developed their own applications. The Times of Malta discontinued its dedicated app in favour of a more mobile phone-friendly design for their portal. Additionally, online formats linked to legacy media (the Times of Malta, MaltaToday, The Malta Independent, Newsbook) have increased their audio-visual content, and the majority of media outlets are present and active on social media platforms, so as to extend outreach.

Apart from straightforward advertising bookings, online outlets like Lovin Malta have a strong lifestyle component, since they target a younger demographic, with events like the Lovin Malta Social Media Awards.

[1] Jon Mallia, https://www.patreon.com/jonmallia.

[2] The SHE Word, https://www.patreon.com/TheSHEWord.

[3] J. Delia, The Critical Angle Project landing page, 2024, https://cap.mt/.