Report authored by Eileen Culloty, Dublin City University

Context

Local media are an important feature of Irish life, which is reflected in high levels of public trust. Unsurprisingly, there is considerable concern about threats to local media and the implications for social cohesion and democracy. The potential for “news deserts” has been raised at parliamentary hearings, at academic conferences, and by the National Union of Journalists.[1]

In 2020, a Future of Media Commission was established to investigate how media can remain “viable, independent and capable of delivering public service aims.”[2] Although the term “news deserts” is not used in the final report, it makes specific recommendations for funding schemes for coverage of local councils and local courts.[3] However, the recommendations are underpinned by a “platform neutral approach to supports for media”,[4] which means the schemes may not necessarily deliver benefits for local media outlets.

Despite its recognised role in Irish life, it is notable that local media are not formally defined. In contrast, the media regulator has a policy on community media[5], which are defined as community-owned and not-for-profit outlets. Local media occupy an ill-defined space between community and national media and the concept is further complicated by the rise of news-oriented websites and social media. Arguably, the failure to define local media may impede recognition of emerging news deserts. Currently, there is little evidence of news deserts in Ireland. Typically, local media cover a specific county and cater to the rural, suburban, and urban areas of that county. The Future of Media Commission noted that each county is served by a local newspaper and, outside Dublin, local radio often accounts for the majority-share of radio listenership. While this situation sounds positive, the reality may not be so healthy as local media encounter many challenges. Nevertheless, it is the rapidly growing suburbs of Dublin city that are at most immediate risk of being news deserts. These suburbs lack a media presence commensurate with their size. Many were served by “free newspapers” that often prioritised entertainment and local events rather than news. In the suburbs of North County Dublin, these and related outlets have closed down, which makes this area a news desert.

[1] National Union of Journalists, DM2023: News Recovery Plan, 2023, https://www.nuj.org.uk/resource/dm2023-news-recovery-plan.html.

[2] The Future of Media Commission website, https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/54a35-the-future-of-media-commission/.

[3] All but one of the 50 recommendations are being implemented by the relevant government department and the media regulator.

[4] Future of Media Commission, Report of the Future of Media Commission, 2022, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/ccae8-report-of-the-future-of-media-commission/.

[5] Broadcasting Authority of Ireland, Community Media Policy, 2021, https://www.bai.ie/en/bai-launches-community-media-policy/.

Main findings

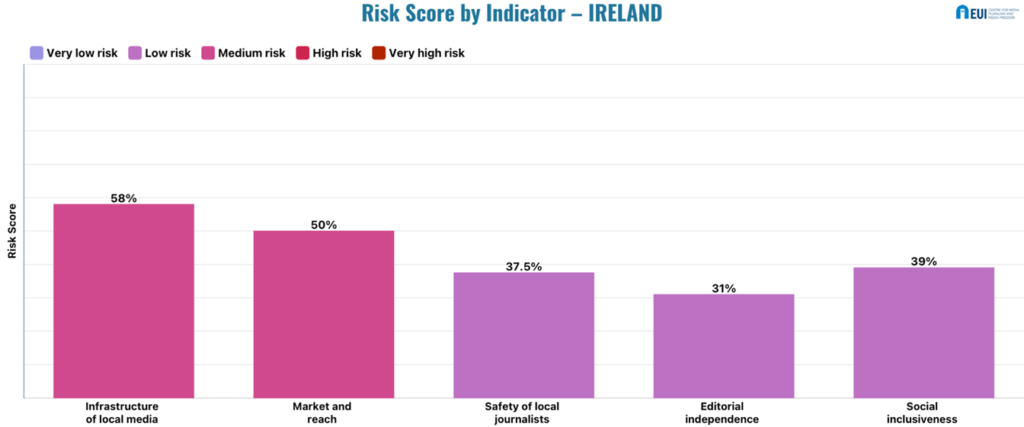

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (58%)

The granularity of infrastructure of local media is assessed as medium risk. Given the small size of Ireland, the infrastructure of local and community media is not overly granular. Local media are often aligned to a particular county[1] and serve the rural, suburban, and urban areas of that county. Historically, there has been a deep connection between local media and the communities they serve. Consequently, the erosion of independent, locally-owned media is considered to be “a threat to community life.”[2] Factors include: declining salaries for journalists, declining news coverage, and the high cost of accommodation and living. According to a 2022 survey, 60% of people under the age of 35 cannot afford to live in the community they would like to live in.[3] These stark conditions have major implications for local journalism as it has been practised historically.

The public broadcaster, RTÉ, has failed to maintain regional correspondents at a time of population growth. Although it has a statutory duty “to establish, maintain and operate … community, local, or regional broadcasting services”[4], current and former staff claim insufficient resources were allocated for regional coverage and regional correspondent jobs have gone unfilled.[5] Notably, the role of Dublin correspondent has remained unfilled for more than a year.

As noted, Dublin and its suburbs are potential news deserts given rapid population growth and a lack of dedicated news coverage. In 2015, a new online and print outlet, the Dublin Inquirer, was founded to address this gap. It represents a substantial effort to report on council meetings and issues of relevance. In contrast, some digital-only outlets operate as a subsidiary of a major UK media group to provide superficial “live news updates” for cities.

[1] The island of Ireland is divided into thirty-two counties with twenty-sixty in the Republic of Ireland. These counties are a major source of personal identity.

[2] National Union of Journalists, Threat to diversity threatens community life, 2022, https://www.nuj.org.uk/resource/threat-to-diversity-threatens-community-life.html.

[3] S. Murray, Almost two thirds of under-35s can’t afford to live in their chosen community, Irish Examiner, 2022, https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-40947479.html.

[4] Irish Statute Book, Broadcasting Act, 18/2009, https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2009/act/18/enacted/en/html.

[5] E. Dalton, RTÉ’s regional reporting teams hollowed out at same time as secret payments, journalists claim, TheJournal, 2023 https://www.thejournal.ie/rte-pay-scandal-staff-6104791-Jun2023/.

Market and reach – Medium risk (50%)

Market and reach is a medium risk. According to the Irish Media Ownership database[1] 26 of the 61 local titles (print and online) represented by the Press Council are owned by just two companies: the UK-based Iconic Newspapers and the Dutch-based Mediahuis. Mediahuis also operates a national weekday and Sunday paper. Of the 31 local and regional radio stations listed in the database, there is some concentration and cross-ownership. For example, Bauer Media Group and Wireless both operate six stations each.

Citing the representative body for local newspapers (Local Ireland), the Future of Media Commission reported that circulation has fallen by 55% since 2008. However, it noted that online reach has significantly expanded the audience in some cases. No comprehensive data is available on this. The past decade has seen restructuring and consolidation in the printing and distribution sectors. Mediahaus recently entered the Irish market and owns ten local titles. It closed printing operations, operates its own nationwide transport network, and plans to phase out all print within 10 years.[2] Other publishers note unfavourable retail conditions as retail multinationals have decimated local shops.[3]

Irish data for the Reuters Digital News Report indicate that the reach of local radio news has declined slightly from 14% in 2019 to 11% in 2023[4]. Overall, however, local radio remains popular and has featured consistently among the top-ten most popular sources of news. In contrast, local newspapers are the 18th most popular source of news. Since 2008, the number of employees in the local print sector has halved and 17 local newspapers have ceased publication. Representatives of the radio sector assert that it is challenging to fill roles in journalism in Ireland’s current climate (full employment, high cost of living).

It is difficult to assess the financial sustainability of local media given the disrupting influence of Covid-19 and the unclear impact of planned measures and funding schemes for news media. Nevertheless, there are reports causing concern from the industry associations that represent local radio (Independent Broadcasters of Ireland) and local newspapers (Local Ireland). Local Ireland reports that more than 90% of all advertising revenue for local and regional newspapers comes from local businesses.[5] There was a dramatic fall in revenue during the pandemic (a 22% decline on average), which was offset by Covid-related government advertising.

Local radio broadcasters reported comparable falls in advertising during the pandemic. The total Irish advertising market contracted by 40% between 2008 and 2012, with the radio market suffering a drop of 45%. They believe they are disadvantaged because they compete with the public broadcaster, which can raise money through commercial advertising and sponsorship. There are also restrictions on the volume of advertising that local broadcasters can carry. However, no local radio station has closed in the past five years, thanks in part to government support during Covid-19. The Future of Media Commission notes that: “while the loss of advertising revenues is a serious problem in itself for print, radio and TV media in Ireland, the wider implications are that significant revenues which previously would have been reinvested into content production and journalism in Ireland are now flowing out of the economy.”[6]

According to the Reuters Digital News Report 2023, 15% of Irish respondents paid for online news. Of these, 6% reported paying for local news. Considering Ireland’s position in the English language market, there is a very wide range of subscription media available and data indicates that a significant slice of digital media spend goes to US and UK titles.

The community media (radio and television) sector in Ireland is diverse in its size and reach and is typically not-for-profit. The Future of Media Commission described the sector as having a challenging financial situation and proposed the development of a Community Media Fund, which will be implemented in 2024.

[1] Media Ownership database website, http://www.mediaownership.ie/.

[2] A. Healy, Mediahuis to phase out daily newspaper printing within 10 years, Irish Examiner, 2023, https://www.irishexaminer.com/business/companies/arid-41107771.html.

[3] Topic Newspapers, Submission to the Future of Media Commission, 2020, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/223520/a3691d25-b6e8-4ce8-9d88-5c26649138f3.pdf#page=null.

[4] C. Murrell et al, Reuters Digital News Report Ireland. Coimisiún na Meán, 2023, https://www.cnam.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/20230609_DNR-Final-Report_STRICT-EMBARGO-00.01-14-June-23_FINAL.pdf.

[5] NewsBrands Ireland and Local Ireland, Pre-Budget Submission to the Department

of Finance, 2022, https://newsbrandsireland.ie/im/2022/07/vat.pdf.

[6] Future of Media Commission, Report of the Future of Media Commission, 2022, p. 98, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/ccae8-report-of-the-future-of-media-commission/.

Safety of local journalists – Low risk (37.5%)

Safety of local journalists is a low risk. Journalists in Ireland benefit from legislation that guarantees minimum wages, regulates open-ended contracts, and sets rules for dismissal procedures, unemployment benefits, and leave entitlements. However, amid soaring accommodation and living costs, the working conditions for journalists are not favourable. The National Union of Journalists[1] represents workers across all media sectors including local, community, and freelance journalists. It appears effective in representing its members and is regularly called upon in media coverage to defend media freedom and the rights of journalists. The NUJ has highlighted pay disputes with employers and bogus self-employment contracts[2].

There are no published figures to ascertain whether spurious legal cases (i.e., SLAPPs) against local media are common or occasional. However, given Ireland’s strict defamation laws, SLAPPs are a recognised problem and a noted threat to media freedom. A report for the International Press Institute found that “legal intimidation affects the full range of Irish media, from the smallest shoestring podcasts and magazines to major broadcasters.”[3] All the Irish reports listed on the Platform to Promote the Safety of Journalists[4] concern defamation cases and the number of alerts has increased. In addition, there are significant reports of the online abuse of journalists, but not physical attacks. The government is implementing an anti-SLAPP legal framework as part of a wider (and long awaited) reform of defamation laws. A draft bill was published in 2023.

[1] The National Union of Journalists (NUJ) predates Irish independence from Britain. It represents journalists from both Britain and Ireland and includes a national council for Ireland.

[2] National Union of Journalists, DM2023: Ireland, 2022, https://www.nuj.org.uk/resource/dm2023-campaign-against-bogus-self-employment-in-ireland.html.

[3] N. O’Leary, Ireland: How the wealthy and powerful abuse the legal system to silence reporting, International Press Institute, 2023, https://ipi.media/ireland-how-the-wealthy-and-powerful-abuse-legal-system-to-silence-reporting/.

[4] Council of Europe, Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists,

Editorial independence – Low risk (31%)

There is currently no legislation aimed at preventing ownership control by political actors. However, there is no suggestion that the media are subject to political interference. This concurs with the assessment of the Irish chapter of the Media Pluralism Monitor.[1] Nevertheless, in terms of risk, it is notable that government intervention in the media sector is increasing, which emphasises the need for transparent and fair procedures.

By looking at the reality of distribution of indirect state subsidies, from January 2023, newspapers and news periodicals, including digital editions, are subject to a 0% VAT rate. Previously, Ireland had one of Europe’s highest rates of tax on newspapers (9%). There are some rules regarding what kind of entity qualifies for the 0% VAT rate. For example, electronic publications devoted to advertising are excluded. In terms of direct subsidies, the media regulator oversees the Sound and Vision[2] funding scheme, which is open to all media producers, including local and community broadcasters. The scheme has rules about eligibility and publishes a list of the amounts awarded to different outlets and producers. This scheme specifically excludes news in favour of “programming that reflects Irish culture, history, language and diversity”. For example, a local radio station could apply for public funds to make a documentary about gardening, but not about news or politics.

Arising from the recommendations of the Future of Media Commission, the media regulator will oversee two local reporting schemes. According to the government minister in charge of media, “the local democracy reporting scheme will help local media keep the public informed on areas such as regional health forums, joint policing committees and local authorities, among other areas. … Likewise, the courts reporting scheme will enable improved reporting from local, regional and national courts.”[3] However, the proposed schemes are “platform neutral”, which means there is no guarantee the funding will go to local media or that local media will be well-positioned to apply. So far, it is not possible to report on fairness and transparency of their distribution.

State advertising rules are unclear. There is no legislation defining the procedures for state advertising and no public register of how such advertising is distributed. The annual Liberties Rule Of Law Report 2023 notes that greater clarity is needed regarding the criteria and processes that determine which media outlets receive state/public advertising.[4] Moreover, the report raises concerns about the use of commercial brokers to place advertisements on behalf of the state and state agencies. In particular, “one agency is owned and controlled by a company which itself owns a significant number of regional newspaper titles.”[5]

Although journalistic content is generally separate from advertising in many/most outlets, the local media sector is heavily dependent on local businesses for advertising. For example, Local Ireland, the body representing local newspapers, notes that before the pandemic, 91% of the advertising revenue for local and regional newspapers came from local businesses. There is no academic research to ascertain whether there is undue commercial influence. As such, one may conclude that there are risks, which could be mitigated by greater transparency, while self-regulatory mechanisms in place would benefit from more explicit safeguards.

While there are no laws to safeguard editorial independence, print/online media are subject to self-regulation if they are members of the Press Council. The Press Council upholds standards – set out in a Code of Conduct – and deals with complaints from the public. Of the 527 complaints reported by the Press Council in 2021[6] (the most recent report), only 25 are related to local news publications. Newspapers are not obligated to be impartial and some have political leanings, but political interference is not common. Journalists working for radio are bound to rules overseen by the media regulator, Coimisiún na Meán. It regulates all content by Irish-licensed broadcasters, both public and commercial. However, the PSM does not operate any local divisions.

In addition to processing complaints about broadcasts, the regulator monitors broadcast content for compliance with broadcasting codes and rules. For example, the Code of Fairness, Objectivity and Impartiality[7] deals with matters of fairness, objectivity and impartiality in news and current affairs content. Broadcasters are bound by strict impartiality rules during periods of elections or referendums. Of the 75 complaints made to the media regulator in 2022, only six concerned local/community radio and only one of these was upheld by the regulator. There is a general consensus that the regulator is fair and independent. While complaints alone are a crude measure of standards, it nevertheless appears that local journalists and local media generally adhere to good standards.

Given the small size of Ireland, there are no local branches of the PSM. The national PSM is bound to an impartiality code for news and current affairs. Complaints about breaches are heard by the media regulator. Currently appointments to PSM boards are exclusively determined by the Minister for Communications and partially subject to the advice of a government committee on media. It is not clear that these decisions are debated by the committee (i.e., on the public record) and there is little to no transparency surrounding how individuals are selected for appointment.

In general, local media provide a diverse range of content in terms of what is covered and whose voices are heard.

[1]R. Flynn, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report: Ireland, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75726/Ireland_results_mpm_2023_cmpf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[2] A. Molloy, Sound & Vision Broadcasting Funding Scheme Round 52 Open, 2024, https://www.cnam.ie/category/sound-vision/.

[3] Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media (Deputy Catherine Martin), Report of the Future of Media Commission: Statements, 2022, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/seanad/2022-09-15/13/.

[4] Liberties Rule Of Law Report 2023, 2023, https://www.liberties.eu/en/campaigns/rule-of-law-report-2023/158.

[5] Liberties Rule Of Law Report 2023, 2023, p. 34, https://www.liberties.eu/en/campaigns/rule-of-law-report-2023/158.

[6] Press Council of Ireland, 2021 Annual Report of the Press Council of Ireland and Office of the Press Ombudsman, 2022, https://www.presscouncil.ie/press-council-of-ireland/press-releases-and-annual-reports/press-releases/2021-annual-report-of-the-press-council-of-ireland-and-office-of-the-press-ombudsman.

[7] Broadcasting Authority of Ireland, BAI Code Of Fairness, Objectivity And Impartiality In News And Current Affairs Implemented,2013,

Social inclusiveness – Low risk (39%)

Social inclusiveness is a low risk. Historically, local media have played a central role in Irish life and demonstrated a strong connection to the communities they serve. This is reflected in high levels of trust.[1]Local media are among the top-five most trusted news outlets with 70% trusting local radio and 69% trusting local newspapers. This is especially notable given the wide range of national and international media available in the English-language market.

Maintaining this trusted connection between local media and communities is vital[2] at a time when the composition of communities is changing as the result of population growth, immigration, and housing developments. However, it is clear that resources (including personnel) are limited, which influences coverage of important issues. Many newsrooms are more dependent on press releases and stories that can be gathered cheaply. This comes at the expense of important, local stories that require time and the in-person presence of reporters on the ground.

There are statutory obligations on the PSM outlet, RTÉ, regarding the official languages of the state beyond English: Irish/Gaelic and Irish Sign Language. Radio stations in other languages, beyond PSM, are obligated to broadcast in Irish for a minimal amount of time. This often includes a news broadcast. Beyond Irish, there is no obligation to broadcast in the languages of minority groups. Nevertheless, non-profit community media tend to be more proactive; an online community station in County Galway operates through 11 languages[3]. Notably, a Polish community group[4] intended to set up community TV channel broadcasting in Polish, but opted to set up a YouTube channel instead of following the official licensing requirements. Beyond broadcasting, there are some free newspapers published in Russian (Nasha Gazeta), Lithuanian (Lietuvis), and Polish (Nasz Glos). These are distributed across towns and cities in different parts of the country. There is evidence of some local outlets publishing content in minority languages, although it is not required or widespread. In addition, research into the attitudes of first-generation Nigerian and Polish migrants highlighted issues with negative stereotyping (e.g., perceived racial stereotyping) and a desire for more space to have their voices heard in news media.[5] Overall, the media were considered useful in helping some minority groups to understand events.

Community media often address marginalised groups in keeping with their ethos. Some national outlets do address marginalised groups with dedicated programming, but this is either relatively new or niche. The PSM no longer provides a dedicated weekly radio programme for people with disabilities and there is no programme dedicated to women, Travellers, or other marginalised groups. In contrast, traditional media have begun to offer more specialised content. For example, a national newspaper has recently developed a women’s podcast, but the reach is not clear.

Campaigners in the areas of disability, gender, and ethnicity have focussed on increasing access to media including access to production jobs and access to exposure for expert sources. For example, Women on Air[6] is an initiative to increase the visibility of female experts and to provide media training for women.

The Future of Media Commission made a number of recommendations to promote equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in media, including: (i) Public Service Media should have a statutory obligation, by 2024, to gather and publish diversity data and (ii) diversity boards that advise producers on, and assist in, the co-creation of content should be created. These recommendations will be implemented in the coming year.

[1] C. Murrell et al., Reuters Digital News Report Ireland, Coimisiún na Meán, 2022, https://fujomedia.eu/digital-news-report-ireland-2022/

[2] National Union of Journalists, Threat to diversity threatens community life, 2022, https://www.nuj.org.uk/resource/threat-to-diversity-threatens-community-life.html

[3] Galway Online Community Radio, https://www.gocomradio.ie/about-us/

[4] K. Masterson, Lights, camera, action for the Midlands Polish Community, Changing Ireland, 2023,

[5] D. Wheathley and L. Rubio, Attitudes towards news media in Ireland: Perspectives from Nigerian and Polish migrants, The Broadcasting Authority of Ireland, 2023, https://www.bai.ie/en/new-research-explores-nigerian-and-polish-migrant-attitudes-to-news-media-in-ireland/.

[6] Women on air website, https://womenonair.ie/.

Best practices and open public sphere

It is difficult to collate the range and scale of innovation in the community and local media sectors. Innovations may not be documented or visible beyond the immediate environment. Innovations among hyperlocal media are even harder to observe. Consequently, efforts to map innovation are necessarily incomplete. For example, Project Oasis[1] identifies 10 independent, digital-native, news organisations in Ireland. Of these, only three cater to a local audience: Dublin Inquirer (Dublin), Tripe+Drisheen (Cork), and Donegal Daily (Donegal).

In some cases, outlets are experimenting with innovative ways to serve audiences. For example, Radio Kerry partnered with the Open Doors Initiative[2] to develop the Speak Up training programme for marginalised groups. More generally, innovation in the radio sector is aided by Learning Waves,[3] a training and networking hub for radio. In the print sector, the Dublin Inquirer[4] took the unusual step of launching a print edition. The outlet works with local artists to create striking cover images that capture aspects of city life.

[1] Project Oasis website, https://projectoasiseurope.com/.

[2] Open Doors Initiative, Radio Kerry and Open Doors Initiative Speak Up Training Programme for marginalised communities, https://www.opendoorsinitiative.ie/Speak-Up-Training-Programme.

[3] Learning Waves website, https://www.learningwaves.ie/.

[4] Dublin Inquirer website, https://dublininquirer.com/.