Lambrini Papadopoulou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Ioannis Angelou, University of Western Macedonia

Context

In Greece, the debate regarding news deserts is non-existent; policymakers, industry professionals and the general public do not engage in discussions on the matter. There is, however, a wider concern about the viability of local media. There is no general definition of local media in Greek law, and they are usually classified into local and regional media, depending on the medium.

Newspapers first emerged at the end of the 18th century and some of the local news outlets that first circulated during this period continue to play a role in Greece’s media ecosystem. Local radio stations were permitted in 1987 and regional television stations in 1989[1]. It is also worth noting that many local media journalists tend to work as freelancers and are generally considered underpaid. Moreover, they frequently find themselves at the receiving end of various threats.

Community media are not officially recognised in Greek law. One approach to understanding them is to view them as alternative media that are independent from political and economic elites, with the primary objective of serving citizens[2].

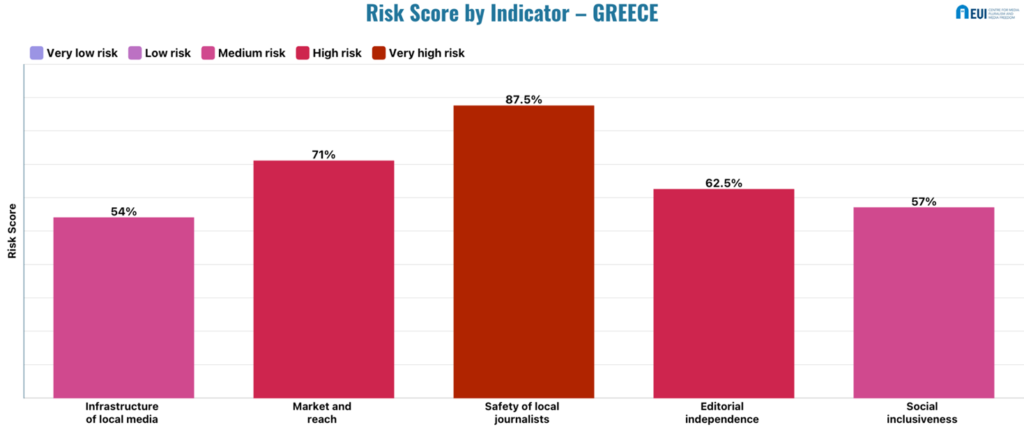

News deserts do not overlap with the most economically deprived regions. An exception is the NUTS2 region of the North Aegean, which has the lowest GDP per capita (13,500). The islands of Samos and Chios within this region have been identified as news deserts due to the absence of daily newspapers. Ipeiros, which is the third most economically deprived area in Greece also includes a news desert, Thesprotia, which has only one news radio station. Looking at the risk level assessment bar chart, the highest risk is related to the indicator on the safety of local journalists.

[1] K. Mayer, “History of Greek press” (Athens: Dimopoulos, 1957); N. Demertzis, and A. Skamnakis, ed., “Local/regional Media and journalism in the New World Communication Order” (Athens: Papazissis, 2000); S. Papathanassopoulos, A. Karadimitriou, C. Kostopoulos, and I. Archontaki, “Greece: Media concentration and independent journalism between austerity and digital disruption,” in J. Trappel and T. Tomaz (eds.), The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How leading news media survive digital transformation (Vol. 2, Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, 2021), pp. 177–230.

[2] E. Siapera, and L. Papadopoulou, “Radical documentaries, neoliberal crisis and post-democracy”, TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 16/1, 2018, pp.1-17, https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i1.851; L. Papadopoulou, “Alternative hybrid media in Greece: An analysis through the prism of political economy”, Journal of Greek Media & Culture, 6/2, 2020, pp.199-218, https://doi.org/10.1386/jgmc_00013_1

Main findings

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (54%)

Greece’s media terrain unfolds with unique challenges and opportunities across rural, suburban, and urban spheres, weaving a tapestry of distinct characteristics and risks.

The rural expanses of Greece grapple with distribution challenges for local media outlets; diminishing selling points and the constraint of low internet penetration. The primary mediums in these areas include radio, television, online platforms, and print media, showcasing both local and national editions. Remarkably, there is a uniformity across regions in the effectiveness of local media services. Even though media operate at a regional level, the challenges faced by rural areas are mirrored in their suburban and urban counterparts. Prefectures like Boeotia, Zakynthos, and Laconia lack local TV stations, emphasising the nuanced risk assessment conducted through interviews with journalistic unions[1].

Contrasting the rural scenario, suburban areas paint a low-risk picture. Local media outlets thrive, employing radio, television, online platforms, and frequently print media, catering to a population well-served by the media spectrum. Despite media offices clustering in urban centres, a noteworthy number of journalists choose to live in suburban or rural areas. This spatial choice fosters a more intimate connection with local news, ensuring that suburban areas find substantial inclusion in news coverage[2].

The urban landscape unfolds with local media leveraging radio, television, online platforms, and print media. However, significant disparities emerge between Athens and Thessaloniki, elevating the risk level to medium. As Athens enjoys a surplus of media offerings, Thessaloniki faces a scarcity, exemplified by the shutdown of news radio stations, which are transitioning their programmes into musical formats[3]. This asymmetry underscores the varied dynamics within urban regions, revealed through interviews with representatives from the Union of Editors of Macedonia Thrace[4].

The journalistic domain presents a high-risk scenario as most journalists find their base in centralised offices. Some reside in rural or small urban pockets but report intermittently on local affairs for national news outlets. The decline in the number of rural journalists can be traced back to the economic crisis of 2008, compounded by low wages and challenging working conditions, leading to a significant exit from the profession. Online media, while present, operate with smaller teams, and instances of dedicated local media in rural areas are scarce. This high-risk scenario prompts concern, with information dissemination primarily centralised in major cities.

Public service media (PSM), Hellenic Radio Television (ERT), scored a high risk in terms of its local and regional news offer. Not bound by law to maintain local correspondents, ERT’s intentional reduction of its network, following a strategic plan, raises questions about comprehensive local coverage. The restructuring of the 19 regional radio stations[5] aligns with streamlining regional offices, potentially compromising the mission to cover the entire geographic territory. The main news agency (Athens-Macedonian News Agency) encounters a medium-risk scenario as local/regional correspondents are declining. More flexible work forms are being adopted, although precise figures remain elusive.

The map you can find at the following link refers to the number of local and regional media in Greece in 2023. The original data source for this visualisation was provided by the non-profit journalism organisation iMEdD (incubator for Media Education and Development) and you can access it here.

[1] Vasilis Peklaris, President of the Union of Editors of Macedonia Thrace,2/6/2023, phone interview.

Themis Beredimas, President of the Union of Magazine and Electronic Press Editor, 3/6/2023, phone interview; Georgios Tsiglifysis, President of the Union of Editors of Thessaly,2/6/2023, phone interview; Kyriakos Kortesis, President of the Union of Editors of the Daily Newspapers, 3/6/2023, phone interview.

[2] Vasilis Peklaris, President of the Union of Editors of Macedonia Thrace,2/6/2023, phone interview.

Themis Beredimas, President of the Union of Magazine and Electronic Press Editor, 3/6/2023, phone interview; Georgios Tsiglifysis, President of the Union of Editors of Thessaly,2/6/2023, phone interview; Kyriakos Kortesis, President of the Union of Editors of the Daily Newspapers, 3/6/2023, phone interview.

[3] Esiemth, “The closure of Real FM 107.1 discredits journalistic work”, Journalists Union of Macedonia and Thrace, 2022, https://esiemth.gr/to-klisimo-tou-real-fm-1071-apaxioni-to-dimosiografiko-ergo

[4] Vasilis Peklaris, 2/6/2023, phone interview.

[5] ERT, “Strategic and Operational Plan 2020 – 2024”, 2020, https://company.ert.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ΕΡΤ_ΣΤΡΑΤΗΓΙΚΟ_ΕΠΙΧΕΙΡΗΣΙΑΚΟ_ΣΧΕΔΙΟ_2020-2024-.pdf

Market and reach – High risk (71%)

Although there are no data or statistics available on local media revenues, insights from interviews with experts and relevant stakeholders point to the conclusion that the last five years have been economically devastating for local media[1]. This is also evident in the number of closures of local news outlets. The risk is very high since, based on data from the National Council for Radio and Television ESR[2] and interviews, 10 local TV stations closed down over the last five years, 13 radio stations ceased operations in 2021, while newspapers also shrank in number. A worrying trend concerned the abundance of radio stations that changed content (and licence) so as to feature only music and no news at all. There are no official data about local online media but all sources agreed they have increased in number over the last five years.[3]

Local newspapers have their own distribution companies and there is no decrease in the number of workers. However, a large number of newspaper kiosks have closed down over the last decade due to the economic crisis, and many local newspapers are now sold at a few supermarkets and bookstores. Regional television media distribute their signal through the company DIGEA, owned by nationwide channels, under conditions of complete dependence on both economic factors and signal quality.

Regarding subsidies, the Greek state provides indirect subsidies for daily and weekly local and regional newspapers through reduced postal service rates. Print media (newspapers and magazines) enjoy a lower value-added tax (VAT) rate than standard goods.

For many years there have been no direct state subsidies given to the media. Direct subsidy schemes for local/regional media were first introduced with Law 4674/2020.

Regarding state advertising, there is no specific legislation for local media outlets. All owners of local media agreed that the government provides an insufficient amount of financial support, and local media outlets operate within an unfavourable business environment.

The risk is also very high for commercial advertising in local media since national news outlets tend to absorb most of the available commercial advertising. When it comes to community media, if understood as an alternative, it is safe to say that the danger is very high as these kinds of outlets receive no financial aid from the state. The concentration of local media ownership is generally insignificant, except for a few cases that can be detected. Regarding people’s willingness to pay for local news there are no available data. However, it should be noted that local radio and TV stations are free of charge.

Concerning the weekly audience reach of local media, Reuters Digital News Report (2023)[4] documented a slight fall compared to last year. However, representatives from unions of local media argued that the reach of local radio shows a general increase, local newspapers maintain a stable reach, while local TV stations have increased their reach[5]. It should also be pointed out that local media seem to be the most trusted among Greek citizens, according to the Reuters Digital News Report (2023).

[1] Antonis Grigoropoulos, President, Panhellenic Union of radio station owners, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Antonis Dimitriou, President, Union of Regional Informative TV stations of Greece, 7/6/2023, phone interview

George Mixalopoulos, President, Association of Daily Regional Newspapers (SIPE), 10/6/2023, phone interview

[2] ESR , “Annual Report for the Year 2021”, https://www.esr.gr/wp-content/uploads/EP2021.pdf

[3] Antonis Grigoropoulos, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Antonis Dimitriou, 7/6/2023, phone interview

George Mixalopoulos, 10/6/2023, phone interview

[4] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, “Digital News Report. Greece”, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/greece

[5] Antonis Grigoropoulos, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Antonis Dimitriou, 7/6/2023, phone interview

George Mixalopoulos, 10/6/2023, phone interview

Safety of local journalists – Very high risk (87,5%)

In Greece, local journalists face significant threats, notably poor working conditions due to the absence of labour and social security legislation. Journalists in local media often face lower salaries, flexible employment terms, and unfilled working hour conditions. A substantial number operate as freelancers, thus experiencing financial vulnerability due to lower net pay after taxes and a lack of social security protection. Those officially classified as part-time workers but working full-time hours face additional challenges, creating an environment where labour rights are inadequately protected.

Freelancers and self-employed journalists in local media receive remuneration considerably below the national average, exposing them to financial precarity. Misclassification as freelancers, despite full-time commitments, further undermines their financial stability and deprives them of social security protection, as emphasised by union representatives in interviews[1], underscoring the urgent need for improved working conditions and legal safeguards.

Physical safety is another pressing concern, with a notable surge in threats and attacks against local journalists, especially online. Despite existing legal frameworks, their ineffectiveness in curbing this trend is apparent. Threats from local actors, including public figures and far-right organisations, persist. The absence of a robust legal framework to guarantee the prosecution of perpetrators exacerbates the risks faced by local journalists, who increasingly find themselves targeted online.

While journalists’ unions at the local level play a crucial role in supporting local journalists and maintaining legal departments, their effectiveness is questionable. Not all journalists are union members, and incidents may go unreported due to various concerns. The unions advocate for state intervention to ensure better working conditions, proposing increased government oversight and transparency measures such as tying state advertising to jobs in local media.

Local journalists often adhere more strictly to codes of ethics due to their close-knit communities. However, interventions at the management level in local media outlets pose challenges to maintaining these standards.

An alarming aspect is the common occurrence of SLAPP cases against local journalists, with no anti-SLAPP legal framework. The increase in such cases, as evidenced by incidents involving journalists like Stavroula Poulemini,[2] underscores the urgent need for government intervention to establish legal safeguards against these attacks. Cases like the one in Chios, where a journalist faces a hefty financial demand from a hospital administrator, highlight the vulnerability of local journalists to legal harassment[3].

[1] Vasilis Peklaris, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Themis Beredimas, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Georgios Tsiglifysis, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Kyriakos Kortesis, 3/6/2023, phone interview

[2] Efimerida ton Syntakton, “Support of Unions to the journalist Stavroula Poulemeni for the SLAPP lawsuit”, 2023, https://www.efsyn.gr/tehnes/media/385692_stirixi-enoseon-sti-dimosiografo-stayroyla-poylimeni-gia-tin-agogi-slapp

[3] Efimerida ton Syntakton, “SLAPP lawsuit against journalist in Chios”, 2022, https://www.efsyn.gr/tehnes/media/365569_slapp-agogi-enantion-dimosiografoy-sti-hio

Editorial independence – Ηigh risk (62.5%)

The Greek constitution prevents individual MPs and MEPs from directly owning certain types of media. Domestic legislation does not contain limitations to direct media ownership by political parties. There are also no provisions limiting indirect control (e.g., through the use of intermediaries) by political parties or MPs. According to ownership data maintained by the National Council for Radio and Television (ESR), there are currently no TV channels directly owned by members of parliament or political parties represented in parliament[1]. However, information as to whether any members of regional/local governments own media is not publicly available, while it has not been possible to assess indirect ownership of audio-visual media by members of parliament and political parties through the use of intermediaries (e.g., family members).

State advertising is not distributed in a fair and transparent way. Αt least 30% of the annual advertising plans of public bodies for each type of media should be allocated to regional media (Art. 4(2) of Presidential Decree 261/1997 as in force). In practice however, according to the sources interviewed, national media tend to receive the majority of state advertising, leaving only a small portion for local media[2].

Τhe Greek state provides indirect subsidies for daily and weekly local and regional newspapers through reduced postal service rates (Art 68(4) of Law 2065/1992 in conjunction with Art 2 of Law 3548/2007 and Ministerial Decision 16682/2011). Print media (newspapers and magazines) enjoy a lower value-added tax (VAT) rate than standard goods (Art. 21(1) of Law 2859/2000 as in force). Direct subsidy schemes for local/regional media were firstly introduced with Law 4674/2020 that introduced a provision for supplying cash grants to newspapers.

Regarding local media and editorial independence from commercial influence, it should first be pointed out that there is no specific legislation on this matter apart from the journalists’ self-regulatory code. According to participants in this study, laws and self-regulation are ineffective, particularly in smaller societies, where commercial influence on editorial content is more prevalent.

Similarly to commercial influence on editorial content, local journalists believe that laws and self-regulation are ineffective in countering political influence. Research into the Greek media system has forcefully demonstrated the existence of political interference in news media, attributable to the close ties that have developed between established private media owners and political elites.[3]

Moreover, the absence of effective self-regulatory safeguards results in journalists being pressured by political and commercial influences.

Τhe National Council for Radio and Television (ESR) is the country’s independent administrative authority that supervises and regulates the radio/television market. It has a remit over all national media, including local media. According to various sources, ESR lacks the necessary resources that would allow it to supervise the media market in a timely and effective manner. Most importantly, there have been various complaints about its dependence on the government and its inability to act in a non-biased manner.

With regard to the political independence of PSM, various articles stipulate that its programmes should be governed by the principles of objectivity, completeness and pluralism, respecting different viewpoints, and be objective and accurate (e.g. Art. 15(2) of the Constitution, Law 4173/2013, Presidential Decree 77/2003). When it comes to independence from political parties, however, the picture is quite different. It should be noted that with the election of New Democracy to the government in 2019, the responsibility for ERT as well as for the public news agency passed to the prime minister himself. The PSM maintains a small network of local correspondents or branches in practice. However, the size of the network has been shrinking over time and is insufficient to cover the whole country. It is also worth noting that New Democracy’s press officer was appointed as ERT’s president. These practices are quite common as every new government tends to appoint a new person to these positions.

Finally, with regard to the issue of content diversity, contrary to national media, local media tend to present a variety of issues and allow different voices to be heard.

[1] TV ownership data is available at: https://www.esr.gr/τηλεόραση/I

[2] Antonis Grigoropoulos, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Antonis Dimitriou, 7/6/2023, phone interview

George Mixalopoulos, 10/6/2023, phone interview

[3] L. Papadopoulou, “Alternative hybrid media in Greece: An analysis through the prism of political economy,” Journal of Greek Media & Culture 6, no. 2, 2020: pp.199-218, https://doi.org/10.1386/jgmc_00013_1. ; S. Papathanassopoulos, A. Karadimitriou, C. Kostopoulos, and I. Archontaki, “Greece: Media concentration and independent journalism between austerity and digital disruption,” in J. Trappel and T. Tomaz (eds.), The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How leading news media survive digital transformation (Vol. 2, Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, 2021), pp. 177–230.

Social inclusiveness – Medium risk (57%)

Greece’s media landscape presents a complex picture of social inclusiveness with varying risks across different dimensions. The risks associated with public service media (PSM) providing news in minority languages are notably high. Specifically, the radio stations in the region of Western Thrace, such as ERA Komotini, do not offer national news in the languages spoken by the Muslim minority in this area (e.g., Turkish). Moreover, there is a dearth of national news in languages spoken by non-legally recognised minorities like Vlachs, Arvanites, or Slavic-speakers. This gap is not only evident in legal frameworks but also in practical implementation, emphasising a substantial deficit in the representation of linguistic and ethnic minorities in the media[1].

While the PSM’s approach is relatively commendable, with a low risk, as per representatives of ERT journalists, it is crucial to note that the primary focus appears to be on protecting minorities rather than actively representing them. Although the coverage is fair and fact-based, extending to various minority groups, including the Muslim community and immigrants, it suggests a commitment to factual representation while falling short of actively providing a robust platform for minority voices[2].

Moving to private media outlets, a medium risk is associated with their news services in some minority languages, which are delivered in a limited and irregular manner. Local private radio stations in regions with a concentration of minorities, such as Xanthi and Komotini, predominantly broadcast in Turkish, addressing the legally recognised Muslim minority[3]. A higher risk is linked to the representation of minorities in private media, raising concerns about potential bias and misleading reporting. Most minorities receive inadequate airtime, leading to distorted narratives, particularly concerning refugees and immigrants. Stereotypical language use and negative associations, such as linking immigrants to increased crime, contribute to a skewed representation, fostering fear and division[4].

The risk escalates to a very high level when considering that there are no specific outlets or channels addressing marginalised groups in the country. This is a stark indication of a significant gap in media representation and engagement for marginalised communities, essentially denying them a voice and perpetuating their exclusion. However, the scenario changes when assessing local media. Generally, they meet the community’s Critical Information Needs (CINs), with low risk, and very few sporadic cases of failure. Interviews with local journalists affirm that local media are closely connected to their communities, fostering high levels of trust. Occasional lapses are attributed to resource constraints, especially the lack of personnel.

[1] Prof. Konstantinos Tsitselikis, University of Macedonia,1/6/2023, mail interview

[2] Vasilis Peklaris, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Themis Beredimas, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Georgios Tsiglifysis, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Kyriakos Kortesis, 3/6/2023, phone interview

[3] Prof. Konstantinos Tsitselikis, 1/6/2023, mail interview

[4] Vasilis Peklaris, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Themis Beredimas, 3/6/2023,phone interview

Georgios Tsiglifysis, 2/6/2023, phone interview

Kyriakos Kortesis, 3/6/2023, phone interview

Best practices and open public sphere

In Greece, the media landscape contains commendable initiatives but also entails several risks. In terms of innovation, high risks prevail, with few organisations engaging in innovative practices[1]. Notable exceptions include IMed Lab, collaborating with Aristotle University for advanced data journalism, and Inside Story, an investigative news media which champions slow journalism and which has also been interviewed within the LM4D project.[2] PressProject and Reporters United contribute to independent investigative journalism, while Efsyn stands out for its cooperative ownership. Despite these, the majority stick to conventional methods, focusing on social media for wider reach.[3]

It is of concern that Greece lacks local citizen and civil society initiatives, with low visibility exacerbating the issue. IMEdD’s Local News programme identifies ‘news deserts’ and probes journalists’ working conditions[4]. PressLocal, of the Journalists’ Union of Macedonia & Thrace, enhances digital trade unionism[5], and the Regional Press Institute (RPI) promotes journalism education and research in regional press history[6]. Limited visibility underscores the need for increased awareness and audience engagement in supporting these initiatives.

[1] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. K., “Digital News Report 2022”, 2022, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf

[2] U. Reviglio and D. Borges, “Newsletters, Podcasts and Slow Media: Successful News Media Strategies to Engage Audiences in the Attention Economy.” Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom, 2023, https://cmpf.eui.eu/newsletters-podcasts-and-slow-media/.

[3] I. Angelou, V. Katsaras, D. Kourkouridis, & A. Veglis, “Social Media Followership as a Predictor of News Website Traffic.” Journalism Practice, 14(6), 2020, pp. 730-748. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1635040.

[4] iMEdD, The Regional Press in Greece, 2023, https://www.imedd.org/local-news/.

[5] #Press_local, “An initiative of the Union of Editors of Macedonia Thrace for work in the local media, Union of Editors of Macedonia Thrace”, 2023, https://press-local.gr/press-local

[6] The Regional Press Institute, 2023, https://www.rpi.gr/?lang=en

Map of Local and Regional Media in Greece

This map shows the number of local and regional media in Greece in 2023. You have the option to filter by format, and NUTS3 region. Hover over a region to view the number of media outlets, including a detailed breakdown by format. Clicking on a specific region provides a detailed list of media outlets in the table below the map. This includes details on the format, prefecture, and region where the outlet is based. The original data source for this visualization was provided by the non-profit journalism organization, iMEdD (Incubator for Media Education and Development), and can be accessed by clicking here. Additional note: Athens/Attica region is excluded from the iMEdD mapping as the project was focused on local media outside of Athens/Attica region.