Sandra Simonsen, Department of Media and Journalism Studies, Aarhus University

Context

Finland has one of the EU’s most robust media systems despite its relatively large size and small population. It ranks number 5 out of 180 countries on the press freedom list and attempts by politicians to influence media content are rare and not tolerated.[1] The foundation of the Finnish news landscape lies in highly professionalised and independent journalism, an arm’s-length principle in media policy, institutionally strong public service media and commercial newspapers, bolstered by a dynamic local press. According to Nielsen,[2]local and regional media play an important role in the media ecosystems. In this respect, Finland is no exception and regional newspapers, supplemented by a diverse local press, can be characterised as key or keystone media. However, the commercial news media rely heavily on advertising revenue from their printed editions, rendering them sensitive to advertising volume and targeting.[3]

Although, Finland still houses a considerable number of print newspapers, both the variety of titles and their circulation have dwindled since the early 1990s. Consequently, concerns arise regarding people’s access to local news, posing risks to diversity.[4] Concurrently, emerging social media groups, notably on platforms like Facebook, and hyperlocal initiatives offer online news or content tailored to specific communities.[5]

Yle, the public service media company, stands as another keystone in the media ecosystem. Yle boasts a network of 31 regional news offices across Finland: 25 serving Finnish-speaking audiences, 8 catering to Swedish speakers, and two dedicated to the Sámi community.

Presently, there are a little over 50 commercial radio channels operating in Finland. State owned media is absent.

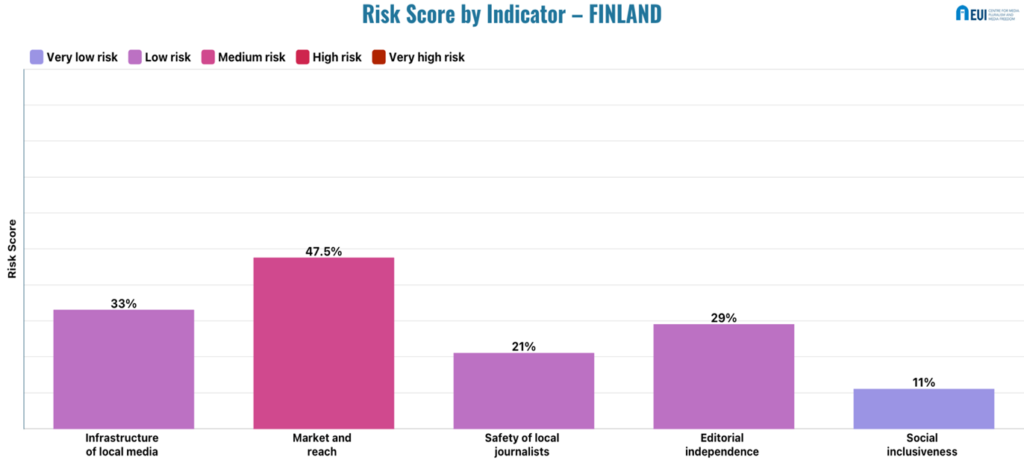

Community media do not legally exist. In 2008, the European Parliament approved a resolution, where member states were recommended to legalise community media and to set up a funding mechanism for non-profit citizen media. However, in terms of legal status, community media are not recognised in Finland or in nine other member states.[6][7] However, hyperlocal media, i.e. initiatives that offer an online news, communication or content service pertaining to a small community such as a village or neighbourhood, is a small feature of the Finnish media ecosystem and mainly consists of around 30 hyperlocal media outlets[8] as well as a few small hobbyist television stations, mainly focused on the Swedish speaking population in Ostrobothnia. The highest risk based on the bar chart below is for the Market and reach indicator.

[1] Reporters Without Borders: Country Report: Finland, 2023, https://rsf.org/en/country/finland

[2] R. K. Nielsen, Local Newspapers as Keystone Media: The Increased Importance of Diminished Newspapers for Local Political Information Environments, 2015, pp. 51-72 in R. K. Nielsen (ed.) Local Journalism. The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media. London/New York: I.B.Tauris.

[3] M. Ala-Fossi, M. Grönlund, H. Hellman and K. Lehtisaari, Media and Communication Policy Monitoring report 2019, 2020, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162144/LVM_2020_04.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[4] M. Ala-Fossi, A. Alén-Savikko, M. Grönlund, P. Haara and H. Hellman, The state of media- and communications policy and how to measure it Final report, 2018, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/160714/04_18_Media- ja-viestintapolitiikan-nykytila.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] J. Hujanen, M. Grönlund, J. Ruotsalainen, K. Lehtisaari and V. Vaarala, The ethics of journalism challenged The blurring boundary between local journalism and communications, Journalistica, 2022, pp. 1-25

[6] M. Nermes, Yhteisömedia: Yli 40 vuotta kansalaisviestintää Suomessakin. Turku: Nomerta, 2013, https://kansalaisareena.fi/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/YhteisomediakirjaNermes2013NomertaSelailukappale.pdf.

[7] K. Bleyer-Simon, E. Brogi, R. Carlini, D. Da Costa Leite Borges,I. Nenadic, M. Palmer, P. L. Parcu, M. Trevisan, S. Verza, and M. Zuffova, Monitoring Media Pluralism In The Digital Era, Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022, 2023, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, European University Institute.

[8] J. Hujanen, K. Lehtisaari; C. Lindén and M. Grönlund, Emerging forms of hyperlocal media. Nordicom Review, 2019. 40(s2), 101-114.

Main findings

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Low risk (33%)

While there is a rich offering of media content in Finland, in recent years there has been talk of news deserts from time to time, for instance feelings expressed by journalists, fearing the shutdown of newsrooms and the loss of workplaces.[1] However, among policymakers, industry professionals and the public the threat has not been recognised as a problem or discussed regularly. News Media Finland, a trade association for newspaper publishers, has clarified the matter. They found that almost all of the 309 municipalities in mainland Finland are covered by newspapers or other media such as public service. Most Finnish municipalities (94%) belong to an area covered by a local or city newspaper. Only 18 municipalities remain outside media coverage. According to the assessment, some regional or provincial newspapers do cover these municipalities as well, albeit maybe not on a regular basis. So, according to this information there are no completely white spots in journalism on the map.[2] However, looking at the home locations of the 14,000 journalists who are members of the Union of Journalists in Finland, there are 61 municipalities out of 309 where no journalist lives and another 57 municipalities with only one residing journalist.[3] The areas most populated by journalists can be found in the Helsinki region. One can of course at the same time argue that municipalities where none or only one journalist lives (40%) are also locations with a very small population.

The media coverage is complete in Finland but there is no data on how “well served” suburban or rural areas are by print and online newspapers, public service media or commercial radio stations. This is difficult to evaluate/not very relevant in a country like Finland with a small population, where the cities are also generally small. Local newspapers, as well as regional newspapers, together with various free and city newspapers, report on events in the different suburbs of the city where they are published. In some of the largest cities, such as Turku, free and city newspapers may also have editions from different regions. In the capital region, several free newspapers focus on the issues of a certain part of the city.

According to The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency (Traficom) roughly half of Finnish households watch television via the terrestrial network, which means using rooftop antennas. The terrestrial TV network reaches over 99.9% of the people in Finland.[4] In 2022, only about 4% of Finns did not have an internet connection. A little over half of Finns use both fixed and mobile broadband at home. 42% use only mobile broadband, i.e. a phone’s network connection, a mobile router and/or a mobile phone.[5]

There might be “news deserts” but they are placed in locations where very few people live. Looking specifically at Lapland, an area covering 25% of Finland or 100,367 km², it has around 179,000 inhabitants, slightly less than the number of reindeer. However, a large part of the population—more than 60%—is concentrated in four cities, Rovaniemi, Tornio, Kemi and Kemijärvi. There is only one daily newspaper, Lapin Kansa, which has journalists in three out of 21 municipalities. The PSM Yle has two newsrooms in Lapland and, in addition, there are seven local papers that are members of the industry association News Media Finland.

[1] J. Räinä, Mitä seuraa, kun alueen ykköslehti lopetetaan ja uutisseuranta kuihtuu? Tutkija arvelee, että kun uutisointi vähenee, kansalaiset vieraantuvat hallinnosta ja politiikasta. Journalisti, 2022, https://journalisti.fi/artikkelit/2022/10/mita-seuraa-kun-alueen-ykkoslehti-lopetetaan-ja-uutisseuranta-kuihtuu-tutkija-arvelee-etta-kun-uutisointi-vahenee-kansalaiset-vieraantuvat-hallinnosta-ja-politiikasta/

[2] R. Virranta, Onko Suomessa uutiserämaata? Suomen Lehdistö, 2021, https://suomenlehdisto.fi/onko-suomessa-uutiseramaata/.

[3] A. Waronen, O. Ponto and J. Pohjavirta, Where do the journalists in Finland live? Katja Mabrouk and three others explain how they work away from others. Journalisti. 2023, https://journalisti.fi/artikkelit/2023/03/missa-asuvat-suomen-journalistit-katja-mabrouk-ja-kolme-muuta-kertovat-tyostaan-etaalla-muista/.

[4] Traficom, Broadcasts in terrestrial TV network, 2023a, https://www.traficom.fi/en/communications/tv-other-audiovisual-services-and-radio/broadcasts-terrestrial-tv-network

[5] Traficom, Monitori service, 2023b, https://eservices.traficom.fi/monitori/area

Market and reach – Medium risk (47,5%)

Finns’ reading of paid-for newspapers and tabloids (print + digital) has remained stable and regular throughout recent years. According to the National Media Survey,[1] 95% of Finns over the age of 15 read newspapers. In numbers, this means more than 4.1 million people. Digital reading is most common in the 35-44 age group, 94%. Those over 65 use the digital channels of newspapers the least, although even three out of four of them (74%) read digital newspapers either in addition to paper newspapers or only in digital form. 55% of all Finns read a printed newspaper. According to Nielsen,[2] local and regional media play an important role in the media ecosystems. Newspapers have also helped people feel attached to their local communities, providing a relevant source of information and space for debate and supplementing the national news arena sustained by the large newspapers, i.e. national and regional newspapers.[3]

Challenges persist in attracting new paying subscribers, particularly among younger demographics.[4] Compared to several Western nations, Finns exhibit slightly lower willingness to pay for digital news.[5]In Finland, newspapers, radio, and television are all heavily concentrated media sectors. Newspaper publishing is presently characterised by frequent mergers and consolidation. Most of the remaining regional newspapers have reached a monopoly-like position in their markets, as they own the majority if not all the local papers and even free sheets in the surrounding area.[6] According to data provided by Statistics Finland[7], the number of newspaper titles (1-7 days a week) have steadily declined during the past decade, going from 320 in 2013 to 274 in 2022.

Public service media Yle reaches a large part of the population, 94%, and even among under 15 year olds the reach is 75%. Local and regional newspapers are among the most trusted media outlets (81% and 79%) but their weekly reach is only 17% and 16% offline, and even less, 12% and 14% online. Finland is also one of the few countries where interest in news has gone up between 2015 and 2023 while a very small proportion of the population is disengaged (2%). This, in combination with the fact that most news consumers prefer to access content directly from news websites and not through aggregators or social media, shows a very strong engagement with news.

Compared to Sweden and Norway, there is very little direct state support for media in Finland, instead the state relies on tax subsidies. Since 2010, the total cumulative amount of indirect aid received through reduced VAT has been around €1.5 billion. In their 2020 report, the VATT Institute estimated the benefit derived from the tax subsidy to be around €125 million.[8]

[1] Media Audit Finland, KMT 2022 LEHTIEN LUKIJAMÄÄRÄT, 2022, https://mediaauditfinland.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/KMT-2022-lukijamaarat-liite.pdf.

[2] R. K. Nielsen, Local Newspapers as Keystone Media: The Increased Importance of Diminished Newspapers for Local Political Information Environments, 2015, pp. 51-72 in R. K. Nielsen (ed.) Local Journalism. The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media. London/New York: I.B.Tauris.

[3] T. Syvertsen, O. Mjøs, H. Moe and G. Enli, The media welfare state: Nordic media in the digital era, 2014, p. 165, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[4] M. Ala-Fossi, A. Alén-Savikko, M. Grönlund, P. Haara and H. Hellman, The state of media- and communications policy and how to measure it Final report, 2018, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/160714/04_18_Media- ja-viestintapolitiikan-nykytila.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] N. Newman, R. Fletcher, K. Eddy, C. T. Robertson and R. K. Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

[6] H. Hellman, Lehdistön alueelliset valtiaat: Sanomalehdistön kilpailu ja keskittyminen merkityksellisillä markkinoilla. Media &/ Viestintä, 2022, 3:1-29.

[7]Statistics Finland, Mass Media Statistics, 2023, https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https://pxhopea2.stat.fi/sahkoiset_julkaisut/joukkoviestintatilasto/data/t202.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

[8] M. Ala-Fossi, M. Grönlund, H. Hellman and K. Lehtisaari, Media and Communication Policy Monitoring report 2019, 2020, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162144/LVM_2020_04.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Safety of local journalists – Low risk (21%)

Minor or serious physical violence is rare in Finland. There are a few instances where journalists have been attacked during demonstrations. On 4 February 2022, at least five Finnish journalists and media workers from Yle (reporter and camera person), Iltalehti (reporters) and MTV3 (reporter) were attacked during the convoy protest, a rally against pandemic restrictions and the increase in energy prices, which took place in Helsinki. In 2023, a journalist working for the newspaper Karjalainen was hit by a person interviewed.[1] However, monitoring and following while conducting journalistic work or disruptions of work such as heckling and interfering during interviews is more common. According to Hiltunen[2] 13-14% report that they have encountered this once a year or less. Physical pressure against journalists may include violence, physically interfering with the performance of journalistic work and tampering with or destroying working equipment. In a 2016 survey[3], 16% of working members of the Union of Journalists reported having received threatening messages in recent years. Instances are few and seem to be random, no trend can be identified. Despite relative gender parity in society, female journalists are most at risk of online harassment and intimidation.[4]

There is no legal framework in place in line with the initiative SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) and the Finnish parliament is sceptical towards several parts of the proposed legislation, which are foreign to the context of law in Finland.[5] However, there are some examples of right-wing politicians using defamation appeals in courts to silence journalists. Two recent court decisions show that, even though the process is slow, defamation appeals do not endanger the freedom of speech in Finland. Finland’s journalists’ union has created a support fund to cover loss of income, therapy and other expenses that can result from stress of this kind.[6]

[1] Reporters Without Frontiers, Country report: Finland, 2023, https://rsf.org/en/country/finland.

[2] I. Hiltunen, Experiences of External Interference among Finnish Journalists, 2019, https://sciendo.com/es/article/10.2478/nor-2018-0016

[3] M. Marttinen, “Hakkaan sinut paskaksi”. Journalisti, 17 March 2016, https://journalisti.fi/artikkelit/2016/03/hakkaan-sinut-paskaksi/.

[4] Reporters Without Frontiers, Country report: Finland, 2023, https://rsf.org/en/country/finland.

[5] M. Fredman, Eduskunnan lakivaliokunta kriittinen EU:n suunnitelmille kiusantekomielessä nostettuja SLAPP-kanteita vastaan, 2022, https://asianajajaliitto.fi/2022/09/eduskunnan-lakivaliokunta-kriittinen-eun-suunnitelmille-kiusantekomielessa-nostettuja-slapp-kanteita-vastaan/

[6] Reporters Without Frontiers, Country report: Finland, 2023, https://rsf.org/en/country/finland.

Editorial independence – Low risk (29%)

The indicator editorial independence scores a low-risk level of 29%. Finland follows the Nordic tradition of self-regulation and recorded instances of abuse are few, with no signs of political control exerted through direct or indirect ownership means found in the country.

When considering the distribution of state subsidies, a very low risk is detected. The Government issued a decree on discretionary government grants for supporting communications and news media in 2023. In addition to national media operations, the aim is to ensure adequate regional and local media services and to prevent the emergence of news wastelands. The discretionary government grants would be targeted especially at local operators.

In terms of state advertising, there is no data available. No overviews are published of who advertises in the media or how much money the media receives from different types of actors through advertising revenue. While this might be seen as a transparency issue, no actual evidence that would suggest concern is found.

By analysing the extent of commercial and political influence over editorial content, it can be stated that self-regulatory safeguards are generally in place and effective. The ethical guidelines for journalists summarise the journalists’ and publishers’ view according to what kind of ethical principles they should operate. In some cases, the journalists’ instructions are stricter than the laws governing mass media. The Council for Mass Media in Finland (JSN) interprets the guidelines, but it is not a court and does not exercise public authority.

At the same time, it has to be highlighted that local commercial media in Finland are still dependent on advertisement – as digital subscriber revenues only grow slowly and mainly go to national media companies. Hence, newsrooms need to balance the watchdog ideal to scrutinise local companies with the need to have a sustainable business model. Furthermore, according to a 2020 survey by the Finnish Newspapers Association (currently News Media Finland[1]), four out of five (79%) newspaper editors had experienced attempts to influence the journalistic content within the last couple of years. Four-fifths (82%) of editors-in-chief said that politicians had tried to influence the content of their publication. In addition, three quarters of editors faced attempts to influence from either readers (75%) or advertisers (72%). Nevertheless, the fact that influential people want to have an impact on editorial decisions, does not mean that editors have no choice but to agree: negotiating attempts to influence editors is considered part of the daily journalism routine.[2]

All national authorities implied in media regulation also have a remit over the local sphere. No signs of concern are detected in this context. With specific regard to the Finnish PSM, Hiltunen notes that the effects of direct political pressure are very limited, but there might be indirect pressures related to politically controlled funding and internal desires to please political parties.[3] Yle’s news and current affairs regional operations include ten Finnish-language and one Sámi-speaking regional operation. Through these, YLE is present in nearly 30 locations across the country.

Finally, in terms of content diversity, it can be argued that local media provide diverse scope of stories to an extent and viewpoints and tone are sometimes non-diverse.

[1]Uutismedian liitto, Vaikuttamispyrkimykset ovat arkipäivää uutismedian päätoimittajille, 2020,

[2] P. Kivioja, Joka kuudes sanomalehden päätoimittaja kokenut vaikutusyrityksiä oman talon johdosta, 2020, https://suomenlehdisto.fi/joka-kuudes-paatoimittaja-kokenut-vaikutusyrityksia-oman-yrityksen-johdosta/.

[3] I. Hiltunen, External Interference in Finnish Professional Journalism, 2022, https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/141075/978-952-03-2486-5.pdf?sequence=5.

Social inclusiveness – Very low risk (11%)

Yle enjoys a high level of trust (85%) while more than half feel that Yle is important to society, and a third consider Yle a significant part of their personal media use.[1] Finland remains the country with the highest levels of overall trust in news (69%) according to the Digital News Report 2023 from the Reuters Institute.[2]

Finland is a tri-lingual country with Finnish, Swedish and Sámi (regional status) as official languages. In total, Yle offers content in twelve languages, including sign-language, Romani, Karelian, English, Russian, and Ukrainian.

The Swedish speaking commercial media sector is vibrant and public service media guarantees services in Sámi. For instance, the media on the Swedish speaking Åland islands, with only 30,000 inhabitants, is exceptional: two daily newspapers, a public service radio and a commercial radio station. YLE has services in Russian and Ukrainian, servicing the largest migrant communities. However, neither public service nor privately owned media serve other minority groups effectively.[3]

National minorities recognised by law, the Swedish speaking Finns and the native Sámi, are served relatively well in terms of airtime; public service media covers national minorities, and the amount of available media content is proportionate to the minorities’ populations.[4] Yle has 32 regional news offices in Finland: 25 Finnish speaking, 8 Swedish speaking and three Sami regional offices, correspondents and assistants around the world. Content in thirteen languages: in Finnish, Swedish and three Sámi languages, in sign language, in plain Finnish and plain Swedish, Romanian, Karelian, English, Russian and Ukrainian.[5] During the COVID-19 pandemic Yle started publishing pandemic-related news in other minority-languages on their website and social media but this initiative ended in May 2021. Overall, unofficial minority languages other than Russian and English were served only through the Yle website and social media, not in broadcasts.[6]

There is no media authority supervising or measuring respect for internal pluralism principles in Finland. Officially news reporting in PSM is steered by the Yle Code of Conduct[7], which is based on the Act on Yleisradio Oy (the Finnish Broadcasting Company; 1380/1993). Yle personnel are expected to comply with Yle’s values and ethical principles in their daily work and all operations. Yle promotes equality, non-discrimination and fairness and is committed to the principles enshrined in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

[1] Yle, Annual Report 2023: Yle’s customer relationships in 2022, 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qcIF-XeIIYlAdZgdFXj_WeDyGwjHXflu/view

[2] N. Newman, R. Fletcher, K. Eddy, C. T. Robertson and R. K. Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf.

[3] M. Mäntyoja and V. Manninen, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2021. Country report: Finland, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2022, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/74688/MPM2022-Finland-EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[4] Act on the Finnish Broadcasting Company, 1380/1993, Section 7, https://www.finlex.fi/sv/laki/kaannokset/1993/en19931380.pdf.

[5] In yearly reports, Yle has special section listing services for special and minority groups, https://yle.fi/aihe/s/10002647

[6] M. Mäntyoja and V. Manninen, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2021. Country report: Finland, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2022, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/74688/MPM2022-Finland-EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[7] Yle, Yle Code of Conduct, 2022, https://yle.fi/aihe/s/yle-code-conduct

Best practices and open public sphere

When discussing to what extent Finnish news media are experimenting with new ways of attracting readers who are willing to pay, innovation is hard to measure. The data are anecdotal and drawn from industry news. As LM4D focuses on local media it unfortunately has to be conclude that there is very little innovation taking place in that field. In a Nordic comparison, Finnish media companies are behind when it comes to certain features such as winning INMA (International News Media Association) awards or getting people to pay for digital news, 21% in Finland compared to neighbours such as Norway at 39%. However, there are a few positive examples, for instance the business daily Kauppalehti has been able to reduce subscriber churn with data analytics[1] and a more inclusive business model[2], while Keskisuomalainen reduced churn with newsletters[3], and the dailies Helsingin Sanomat and Ilta-Sanomat experimented with big stories to attract more paying subscribers.[4]

[1] International News Media Association, L. Tuomela, Kauppalehti’s FOMO page proactively reduces churn, saves 30% of subscribers entering flow, 2023, https://inma.org/blogs/digital-subscriptions/post.cfm/kauppalehti-s-fomo-page-proactively-reduces-churn-saves-30-of-subscribers-entering-flow.

[2] International News Media Association, J. Suhonen, Kauppalehti details its journey of building a more inclusive business model, 2023, https://inma.org/blogs/digital-subscriptions/post.cfm/kauppalehti-details-its-journey-of-building-a-more-inclusive-business-model.

[3] International News Media Association, M. Niskanen, Keskisuomalainen Group reduced subscriber churn with newsletters, 2023, https://inma.org/blogs/ideas/post.cfm/keskisuomalainen-group-reduced-subscriber-churn-with-newsletters

[4] International News Media Association, Helsingin Sanomat, SML model, 2023, https://inma.org/best-practice/Best-Innovation-in-Newsroom-Transformation/2023-340/SML-model