Report authored by Signe Ivask, University of Tartu.

Context

“News deserts” are occasionally discussed in Estonia, which has a land area of 42,750 km (45,339 km²)[1] and a population of 1,365,884,[2] but they are not in a sustained focus. The issue of insufficient coverage in the outskirts arises periodically, as evidenced by an analysis conducted by the University of Tallinn.[3] This discussion revolves around the closure of numerous local news outlets, exemplified by cases like Koit or Meie Maa.[4] Some local media, such as Hiiu Leht, undergo changes in ownership, when acquired by businessmen or investors.

A recent study contributes to the discourse, emphasising that even regions deemed “covered by a local newsroom” may be considered news deserts.[5] This is attributed to the fact that journalists lack the necessary resources to fulfil their professional watchdog role, a concern echoed by journalism professor Halliki Harro-Loit.[6] Though not consistently at the forefront, these discussions shed light on the challenges within Estonia’s local media landscape.

The legal framework in Estonia does not provide a specific definition for “local media” and “community media”. In practice, however, local media is commonly associated with specific regions and municipalities. Local outlets typically focus on issues of relevance for the area of their municipality or region. Community media, on the other hand, are hyperlocal outlets initiated by community members out of enthusiasm. Despite the absence of a regulatory or legislative definition, community media thrive at the local level. The hyperlocal nature of these media outlets is attributed to the size of Estonia and its distinctive communities. Given the country’s population density of 31.4 people per km² [7] covering larger regions becomes challenging due to a lack of enthusiastic contributors and the distances between larger municipalities.

Regarding internet penetration, Estonia boasts a high rate of 92.4%.[8] However, 92,255 people lack bandwidth connection.[9] Notably, small islands and areas in North-East, South-West, and North-West Estonia face challenges in bandwidth connectivity.[10] As data collected for this report shows, these areas are potential news deserts.

[1] ‘World Bank Open Data’, World Bank Open Data <https://data.worldbank.org>

[2] Estonia Statistics, ‘Avaleht | Statistikaamet’ https://www.stat.ee/et

[3] U. Rohn et al, ‘Eesti sõltumatu kohaliku ajakirjanduse loodavad väärtused, väljakutsed ja arenguvõimalused’, 2019.

[4] ‘Ajaleht Meie Maa lõpetas ilmumise: “Parem õudne lõpp, kui lõputu õudus,” ütleb lehe tegevjuht’, Saarte Hääl, 2022 https://saartehaal.postimees.ee/7506255/ajaleht-meie-maa-lopetas-ilmumise-parem-oudne-lopp-kui-loputu-oudus-utleb-lehe-tegevjuht

[5] S. Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, ‘Locked Up: Local Newsrooms Managing a Digital Shift at the Centre of the Covid-19 Outbreak’, Journalism Practice, 0.0 (2023), 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2023.2266483 .

[6] A. Harrik, ‘Ajakirjanduse Professor: Võim Peab Ikka Ajakirjandust Natuke Kartma | Ühiskond | ERR’, 2023 https://novaator.err.ee/1609107689/ajakirjanduse-professor-voim-peab-ikka-ajakirjandust-natuke-kartma

[7] ‘Rahvastik | Statistikaamet’ https://www.stat.ee/et/avasta-statistikat/valdkonnad/rahvastik

[8] ‘Eestlased Kasutavad Internetis Enim E-Maili Ja Internetipanka, Kasvab Ettevõtete Turvateadlikkus | Statistikaamet’ https://www.stat.ee/et/uudised/infotehnoloogia-ettevotetes-ja-leibkondades-2022

[9] E. Lauk, ‘Digitaalne lõhe lairibaühenduse kättesaadavuse näitel Eestis’, unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Tartu, 2021.

[10] ‘Sideteenuste Katvuse Rakendus’ https://www.netikaart.ee/tsaApp/

Main findings

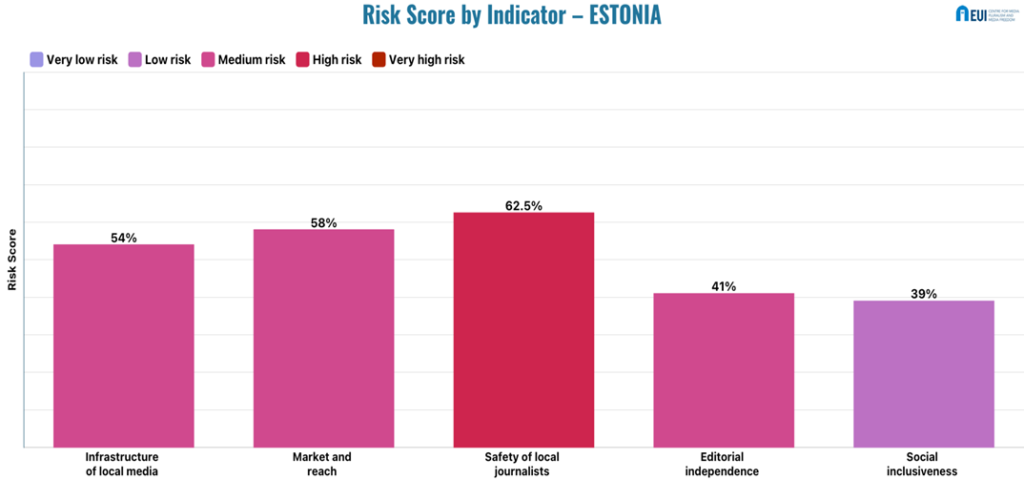

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (54%)

The landscape of local media, spanning television, radio, press, and their online counterparts, reflects a rich tapestry influenced by a unique historical context. However, there is a lack of local TV channels.[1] The radio scene is diverse, featuring stations such as MartaFM, Kesk-Eesti Tre Raadio, Nõmme Raadio, Tallinna Pereraadio, Raadio Kadi, Raadio Tallinn, Ruut FM, SSS-Raadio, BFBS Radio, and BFBS Radio 2. [2]Regarding the press, there are 151 local media outlets, encompassing citizen initiatives, local government publications, and cultural movements’ information brochures, with 25 dedicated journalistic outlets contributing to the media landscape.[3] Delving into the nuanced sphere of community media, religious stations like Kuressaare Pereraadio, Narvskoje Semeinoje Radio, Tallinna Pereraadio, and Radio Eli play integral roles.[4] However, community-led initiatives, as identified by Associate Professor of Journalism Sociology (University of Tartu) Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, pose a nuanced challenge to categorisation. Entities like Nõmme Raadio, SSS-Raadio, and Tõrva Raadio exist in a grey area, straddling community and alternative forms of media, sometimes opposing the mainstream media and dispersing conspiracy theories.[5]

The print media in the community sphere features publications like Uma Leht, setomaa.ee, Viimsi uudised, Peipsirannik, Põltsamaa Valla Sõnumid, läänlane, and Elva elu. Notably the only local TV channel, AloTV in Tartu, functions solely as a music channel without information dissemination.[6]

Community radio faces regulatory hurdles, with temporary frequency licences available; the acquisition of a permanent frequency licence proves elusive due to a lack of adequate resources and a viable business model. Social media platforms, while hosting local conversations, lack journalistic ambition or curated editorial interventions.

Moving away from bigger towns in Estonia, to rural areas, local media outlets exist, but their distribution faces challenges, including a decreasing number of selling points[7] and low internet penetration.[8] Rural areas are prevalent on both the islands and the mainland of Estonia, for example, in Northern-Western Estonia or certain areas within the Western regions, but they can also be found in the middle of Estonia as well as in the Eastern parts (e.g., the coast of lake Peipsi). These areas exhibit a strong correlation with the local populace and are positioned distantly from larger municipalities or cities, lacking shops and kiosks in the area. Suburban and urban areas also show medium-risk scenarios, with limited diversity in local media outlets.[9]

Common forms of local media include print and online, but the overall risk level suggests potential gaps in coverage. In the last five years, there has been a medium-risk decline in the number of local journalists, particularly those based in rural or small urban areas. [10] This trend may impact the coverage of local communities and events.

The Public Service Media (PSM) – ERR (Eesti rahvusringhääling) maintains a stable network of local correspondents or branches, ensuring widespread coverage.[11] However, the main news agency BNS[12] poses a higher risk, as it operates primarily from the capital city.

[1] ‘NETI: /INFO JA MEEDIA/Ajalehed/Kohalikud’ https://www.neti.ee/cgi-bin/teema/INFO_JA_MEEDIA/Ajalehed/Kohalikud/

[2] ‘NETI: /INFO JA MEEDIA/Ajalehed/Kohalikud’.

[3] S. Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, 2023.

[4] ‘NETI: /INFO JA MEEDIA/Ajalehed/Kohalikud’.

[5] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, Associate professor of Journalism Sociology (University of Tartu, Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[6] ‘NETI: /INFO JA MEEDIA/Ajalehed/Kohalikud’.

[7] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[8] ‘Sideteenuste Katvuse Rakendus’.

[9] U. Rohn et al., 2019.

[10] S. Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, 2023.

[11] ‘Korrespondendid | Korrespondendid | ERR’ https://info.err.ee/988701/korrespondendid

[12] ‘BNS Cover Contacts’ https://www.bns.ee/en/contacts_en.html

Market and reach – Medium risk (58%)

In certain regions, community outlets primarily serve as advertising mediums, playing a minimal journalistic role. This further complicates the assessment of advertising revenues within the media sector. Adding to this lack of clarity is the absence of a clearly defined community media sector, which hinders discussions on advertising revenue trends. Therefore, there is a pressing need for a more nuanced understanding of the media landscape in this unique context.[1]

Estonia’s local media revenue landscape is characterised by medium risk, indicating a delicate balance between stabilisation and decline. Ragne Kõuts-Klemm’s[2] researchunderscores the impact of changing ICT dynamics and digitalisation requirements on independent news outlets, exacerbating financial constraints. Despite national-level revenue stability, local outlets face unique challenges, emphasising the nuanced nature of the economic landscape.

A high-risk trend emerges with a significant increase in closures of local media outlets, particularly in the print sector[3]. However, the surge in online outlets offers a partial offset to this trend. Print media, being the primary local journalism platform in Estonia, bears the brunt of closures, underscoring the need for adaptive strategies.[4]

The medium-risk assessment of the supply distribution chain underlines adequacy in certain sectors but exposes vulnerability in others. Concerns over decreasing points of sale, distribution companies, and workers, especially in rural areas, reflect challenges in ensuring timely newspaper delivery.[5]

Ragne Kõuts-Klemm’s assessment underscores a challenge in defining community media in Estonia. Despite the presence of community-led outlets, they fall short of meeting the criteria due to the lack of a sustainable business model and adequate financing. Attempts to establish community publications have been short-lived, hindered by financial constraints. For instance, publications like Setomaa or Uma Leht, sustained by state support through SA Kultuurileht, do not align precisely with the community media definition, which typically requires independence from state-provided support.[6]

Regarding government financial support, there is a partial agreement on sufficiency, acknowledging measures like VAT reduction, home delivery grants, and COVID-19 crisis funds.[7] However, concerns persist due to irregular provision and anticipated changes in VAT rates.[8] Notably, the support predominantly benefits print journalism, leaving gaps in support for TV and radio, underscoring potential imbalances.

The medium-risk assessment regarding the situation for commercial advertisement revenue recognises a decline in specific sectors, aligning with broader economic trends. Ragne Kõuts-Klemm[9] underscores the formidable challenges posed by global internet giants, diverting advertising revenue away from local media outlets. The scenario calls for strategic adaptations in response to changing advertising dynamics.

Insufficient data on community media outlets leads to challenges in assessing trends and financial support. According to Ragne Kõuts-Klemm,[10]Estonia lacks community media per se, with limited sustained outlets. The absence of a defined business model and financing hampers community media’s growth. This gap is notable in the absence of diversified voices in the local media landscape.

Ownership concentration poses a very high risk, with Eesti Meedia affiliation covering a significant portion of local outlets, influencing the largest municipalities.[11] While some outlets, like Pärnu Postimees,[12] maintain autonomy, the overarching influence raises concerns about diverse media ownership.

Regarding audience willingness to pay for local news, a medium-risk assessment indicates disparities across sectors. Subscription-based models for print and larger online outlets show promise, with growing willingness to pay for digital content.[13] However, challenges persist, especially for TV and radio, which largely operate on a free model.

The existence and effectiveness of funds for innovation was scored high risk, signalling challenges in accessing resources for local newsrooms. While public funds from the European Commission are available, the application process poses barriers.[14] Smaller newsrooms without extensive project presentation skills face difficulties accessing these grants. Finally, the lack of data on local media’s audiences (as it is considered a trade secret) prevents a comprehensive analysis of the related recent trends.

[1] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, Associate professor of Journalism Sociology (University of Tartu, Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[2] Meediapoliitika Olukorra Ja Arengusuundade Uuring, ed. by Ragne Kõuts-Klemm and others (Tartu : Tallinn: Tartu Ülikooli ühiskonnateaduste instituut ; Tallinna Ülikool, 2019).

[3] ‘Põlvamaa ajaleht Koit lõpetab juulist ilmumise’, Uudised, 2019 https://lounapostimees.postimees.ee/6562732/polvamaa-ajaleht-koit-lopetab-juulist-ilmumise

[4] S. Ivask and L.Waschková Císařová,2023.

[5] Lauri Habakuk, Local journalist of Pärnu Postimees (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 5.10.2023.

[6] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[7] Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[8] ‘Meedialiidu juht: ajakirjanduse käibemaks nulli!’, Äripäev https://www.aripaev.ee/arvamused/2021/12/09/meedialiidu-juht-ajakirjanduse-kaibemaks-nulli

[9] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[10] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[11] ‘Margus Linnamae to Become Sole Owner of Eesti Meedia’, Estonian News, 2015 https://news.postimees.ee/3307051/margus-linnamae-to-become-sole-owner-of-eesti-meedia

[12] Lauri Habakuk, Local journalist of Pärnu Postimees (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 5.10.2023.

[13] Lauri Habakuk, Local journalist of Pärnu Postimees (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 5.10.2023.

[14] Anonymous editor in Estonian Local outlet, face-to-Face interview on Opportunities of Local Media, 2021.

Safety of local journalists – High risk (62.5%)

In evaluating the working conditions of journalists in local media outlets, this report relies on the author’s research.[1] The overall assessment indicates a medium risk level, reflecting generally acceptable conditions. The consistency in working conditions between regional and national journalists is acknowledged,[2] with some variations observed among less successful local outlets. Changes in the hiring systems, such as reliance on freelancers, raise concerns as freelancing lacks social security benefits, leaving journalists responsible for their own well-being.[3] Some newsrooms offer psychological counselling and additional health insurance, while others provide perks like lunch discounts, albeit not universally.[4]

For freelancers or self-employed journalists, the evaluation indicates a high-risk scenario. The remuneration for freelancers is often below the country’s average salary, and they lack social security protection[5]. Establishing a company requires meeting minimum salary levels, which presents financial challenges. Former freelancer Tiina Kaukvere emphasises the struggle for a stable income, with monthly earnings fluctuating significantly. The social tax structure adds complexity, making access to social benefits contingent on paying specific amounts to the tax office.[6]

Concerning physical safety, the assessment suggests a medium risk, with occasional attacks and threats, particularly online.[7] The COVID-19 outbreak highlighted safety equipment shortages,[8] impacting local journalists. Instances of online hostilities are on the rise, posing challenges, especially for younger and less experienced journalists. The legal framework to prosecute perpetrators is in place but may not be entirely effective, with limitations noted in protecting journalists from SLAPP cases and online hostility.[9]

The presence and effectiveness of journalists’ organisations at the local level are deemed to be at very high risk. Critical perspectives, including those from practitioners, highlight scepticism toward existing associations.[10] The lack of clear actions and trustworthiness raises concerns, and meetings predominantly occur in larger cities, leaving many local journalists isolated.

Professional standards are identified to be at medium risk. Larger local news outlets are generally committed to ethical journalism, adhering to codes of conduct.[11] Smaller regional outlets may not consistently follow professional standards, sometimes disseminating unedited information from local governments without performing a watchdog role.[12]

Overall, the comprehensive assessment highlights nuanced challenges in Estonia’s local media landscape, emphasising the need for targeted interventions to address poor working conditions, safety concerns, organisational support, adherence to professional standards, and legal protections for journalists.

[1] S. Ivask and A. Lon, ‘“You Can Run, but You Cannot Hide!” Mapping Journalists’ Experiences With Hostility in Personal, Organizational, and Professional Domains’, Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78.2 (2023), 199–213 https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958231151302

[2] Lauri Habakuk, Local journalist of Pärnu Postimees (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 5.10.2023.; Raul Vinni, Local journalist of Hiiu Leht (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 6.10.2023; Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023; Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, Associate professor of Journalism Sociology (University of Tartu, Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[3] ‘Law of Obligations Act–Riigi Teataja’ https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/506112013011/consolide

[4] Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[5] Tiina Kaukvere, Freelance journalist in Estonia, face-to-face interview on freelancing in Estonia, 5.10.2023; Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[6] Tiina Kaukvere, Freelance journalist in Estonia, face-to-face interview on freelancing in Estonia, 5.10.2023.

[7] S. Ivask, L. Waschková Císařová and A. Lon,‘“When Can I Get Angry?” Journalists’ Coping Strategies and Emotional Management in Hostile Situations , Journalism, 2023 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14648849231199895

[8] S.Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, 2023.

[9] Lauri Habakuk, Local journalist of Pärnu Postimees (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 5.10.2023.

[10] Raul Vinni, Local journalist of Hiiu Leht (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 6.10.2023.

[11] Bruno Lill, ‘Liikmed’, Eesti Meediaettevõtete Liit, 2023 https://meedialiit.ee/liikmed/

[12] S. Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, 2023.

Editorial independence – Medium risk (41%)

In Estonia, there is no regulation preventing political control of the media through direct or indirect ownership. This results in cases where political control is evident, prompting a medium-risk evaluation of this specific indicator. In an interview conducted for this study, Associate Professor Ragne Kõuts-Klemmdiscussedthe cases of Vooremaa (owned by politician Aivar Kokk), Tre radio (owned by politician Siim Pohlak), and Postimees (a national news outlet, which also owns local outlets; the extent of political influence is still undetermined).[1]At the same time, political party media are considered as a separate phenomenon, not adhering to journalistic criteria, and publicly disclosed in the business register.

Regarding state subsidies to private local media, the risk is considered low. Media expert and experienced editor-in-chief Väino Koorberg,outlined the presence of various types of subsidies, including VAT exemptions, home delivery support, and unemployment fund wage compensation. The distribution of grants for Russian-language news outlets is deemed fair and transparent, with explanations provided by recipients.[2]

Advertising by the state is limited to the dissemination of crucial information during crises, and only in public broadcasting, where a legal obligation to broadcast official announcements of constitutional state bodies, maintaining transparency, is in place.[3]At the same time, state-owned companies can advertise themselves in other channels, including in local media. However, no data could be found regarding the distribution of advertising by state-owned enterprises.

The independence of local media editorial content from commercial influence is assessed as medium-risk. While Estonia has a code of ethics for journalists and self-regulatory institutions, not all outlets, especially small regional ones, have signed it.[4] Laws exist to prevent misleading advertisements, and public broadcasting cannot show commercial advertisements.[5]

The independence of local media from political influence is also medium-risk: while there is a code of ethics, there are some cases where politics is very close, and signs of interference are observed. Still, local media is generally considered independent, with efforts made to keep politics out of editorial offices.[6]

In Estonia there is no general media authority as such. The Consumer Protection and Technical Monitoring Authority[7] (TTJA)regulates the audio-visual media sector, but their competencies do not extend to print and online media. These authorities have a remit over local media, and their actions do not raise elements of concern, prompting a low-risk evaluation.[8]

The Estonian PSM ERR does not have local branches, but rely on correspondents displaced at the local level. In terms of independence, its Board consists of politicians or politically motivated individuals[9], allowing for occasional interference. The budget dependency on the government and parliament also raises concerns.[10]

Experts perceive the content diversity in local media as moderate. Observers point out a tendency towards “comfort zone” reporting, where journalists tend to steer clear of conflict with local leaders[11].

[1] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[2] Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[3] ‘Ringhäälinguseadus–Riigi Teataja’ https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/831359

[4] Bruno Lill, ‘Liikmed’, Eesti Meediaettevõtete Liit, 2023 https://meedialiit.ee/liikmed/

[5] ‘Consumer Protection Act’’ https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/521012014011/consolide

[6] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm,face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.

[7]‘Private Client | Consumer Protection and Technical Regulatory Authority’ https://ttja.ee/en

[8] However, it is worth noticing that TTJA operates under the governance of Economic Affairs and Communications

[9] ‘Eesti Rahvusringhäälingu Nõukogu | Juhtimine | ERR’ https://info.err.ee/981730/eesti-rahvusringhaalingu-noukogu

[10] ERR | ERR, ‘Budget 2024: Who Gets What?’, ERR, 2023 https://news.err.ee/1609117022/budget-2024-who-gets-what

[11] Editor in Estonian Local outlet, face-to-Face interview on Opportunities of Local Media, 2021; Raul Vinni, Local journalist of Hiiu Leht (Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 6.10.2023

Social inclusiveness – Low risk (39%)

The risk associated with PSM broadcasting in minority languages is considered medium. The Broadcasting Law mandates contributions to the preservation and development of the Estonian nation, language, and culture[1]. While there is no specific regulation about broadcasting in other languages, the government supports the development of Russian-language outlets and programmes[2]. Russian is the primary focus, with the dedicated TV channel ETV+ and Raadio4 under the PSM, along with news.err.ee providing Estonian news in English. However, languages like Finnish and Ukrainian are not covered.

The representation of minorities in PSM’s news reporting is deemed low risk. The PSM is praised for precise, factual coverage, and there is a high level of trust among the audience.[3]. An ethics counsellor oversees the coverage.[4]

Private media outlets, as assessed, pose a low risk in offering news services in minority languages. Russian-language journalism is actively developed, and there are also Finnish-language and Ukrainian news services.[5]

The representation of minorities in news reporting by private media outlets is assessed as very low risk. Ukrainians and Russians in Estonia receive substantial coverage, with factual reporting in national dailies and TV shows.[6] The Press Councils oversee accuracy.[7]

There are no available data on the question of outlets or channels addressing marginalised groups (e.g. women, youth, elderlies, people with disabilities); according to Ragne Kõuts-Klemm,[8] there are no specific outlets in Estonia targeting marginalised groups. The PSM has focused on providing news accessibility for people with hearing disabilities.

Regarding the provision of sufficient public interest news by local media, therisk is assessed as medium. Some local media outlets may prioritise softer topics or avoid conflict-related issues due to business-related pressures, such as external influences or the pursuit of higher online engagement.[9]

Media experts say that the extent to which local media outlets engage with their audience and local communities is moderate. Estonian local journalists are closely connected to the communities they serve, often engaging in direct communication. However, interaction fluctuates, and audience research is infrequently conducted due to resource constraints.[10] Despite this, trust in Estonian journalism remains high, with over half of the population relying on the media for information.[11]

[1] ‘Ringhäälinguseadus–Riigi Teataja’.

[2] ‘Riik Toetab Eesti Venekeelset Erameediat Miljoni Euroga’ https://www.postimees.ee/7721173/riik-toetab-eesti-venekeelset-erameediat-miljoni-euroga

[3] ERR | ERR, ‘Survey: Trust in Estonian Media Growing’, ERR, 2022 https://news.err.ee/1608540526/survey-trust-in-estonian-media-growing

[4] ‘Eetikanounik | ERR’ https://info.err.ee/k/eetikanounik

[5] ‘Естонська продукція потрапила в Україну’, Україна, 2022 https://ukraina.postimees.ee/7471463/estonska-produkciya-potrapila-v-ukrajinu

[6] Väino Koorberg, Estonian journalism expert, E-mail exchange on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[7] Bruno Lill, ‘Pressinõukogu’, Eesti Meediaettevõtete Liit, 2023 https://meedialiit.ee/pressinoukogu/

[8] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, Associate professor of Journalism Sociology (University of Tartu, Estonia), face-to-face interview on Local Media in Estonia, 9.10.2023.

[9] S. and L. Waschková Císařová,2023.

[10] S.Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová,2023.

[11] ‘Uuringud | Riigikantselei’ https://www.riigikantselei.ee/uuringud?view_instance=0¤t_page=1

Best practices and open public sphere

The landscape of news media organisations reveals a medium risk level of experimentation with innovative responses to improve reach and audience engagement. Several newsrooms are undergoing a process of digitalisation, incorporating remote work for journalists, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into their workflows, and exploring new journalistic products, such as long reads with audio and audio-visual elements. Social media storytelling and the implementation of new business models, including paywalls, are also observed in certain local newsrooms.[1] News media in Estonia are actively seeking ways to understand their audience better and tailor content based on audience metrics. Notable attempts at innovation include Ekspress Group‘s conference, where journalists shared their stories, aiming to bring journalistic work closer to the audience. Levila, in particular, is acknowledged for efforts to break out of the elitism trap, creating repetitive stories for the community and extending its presence beyond Tallinn. However, significant success stories in terms of experimentation are limited, with relatively little ground-breaking exploration occurring, especially at the local media level.[2]

There is a lack of citizen or civil society initiatives addressing the decline of local and community news provision. The only notable effort mentioned is that of the Journalists’ Association, which is advocating for the recognition of journalism as a creative industry, aiming to secure more funds. Despite their focus on this matter, they have not yet succeeded in making it a reality.

[1] S. Ivask and L. Waschková Císařová, 2023.

[2] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, face-to-face interview, 9.10.2023.