Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Cyprus

Report authored by Nicholas Karides, Institute for Mass Media, IMME; Christophoros Christophorou, Independent expert.

Context

The first newspaper in Cyprus was launched in 1878 at the beginning of British colonial rule. Public Broadcasting was launched under British rule in 1953 (radio) and the first TV programmes came in 1957. With independence in 1960 the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation was established; private broadcasting followed in 1990. The term “local” is included only in the 1998 Law on Radio and Television Organisations to designate radio and television, but the term has been retained in the Law only for radio[1]; after the shift to digital television in 2011, local television stations either disappeared or were turned into national coverage channels. Community media is not recognised in any law. The first de facto community media were bulletins published mainly by municipalities.

Television licences are for nation-wide coverage. Some local radio stations became national after the digital shift in 2011 and modified their content. While there are 17 local stations only five offer news and current affairs programmes, with the rest offering mostly music or religious content[2]. However, while five local channels offer editorial content, as noted above, it cannot be confirmed that the daily needs of local communities are being addressed. In urban and suburban areas in Paphos and Limassol there are only a couple of print media, but no daily; numerous online media outlets and a limited number of local radio stations airing news and current affairs programmes are operating in the Larnaca, Limassol, Paphos and Famagusta (the district’s free part) areas. Print weeklies with local content offer limited coverage of rural communities. In assessing whether rural areas in Cyprus are well served by local media outlets this research considers that Cyprus is at high risk as only some local media exist in its rural areas, but these cannot be said to reach the population living in the most remote areas of the country.

[1] The Radio and Television Broadcasters Law 7(I)/1998 https://crta.org.cy/en/assets/uploads/pdfs/FINAL%20CONSOLIDATED%20LAW%20up%20to%20Amendment%20197(I).2021.pdf

[2] Cyprus Radio Television Authority, List of Radio Television Organisations, https://crta.org.cy/katalogos-organismon

Main findings

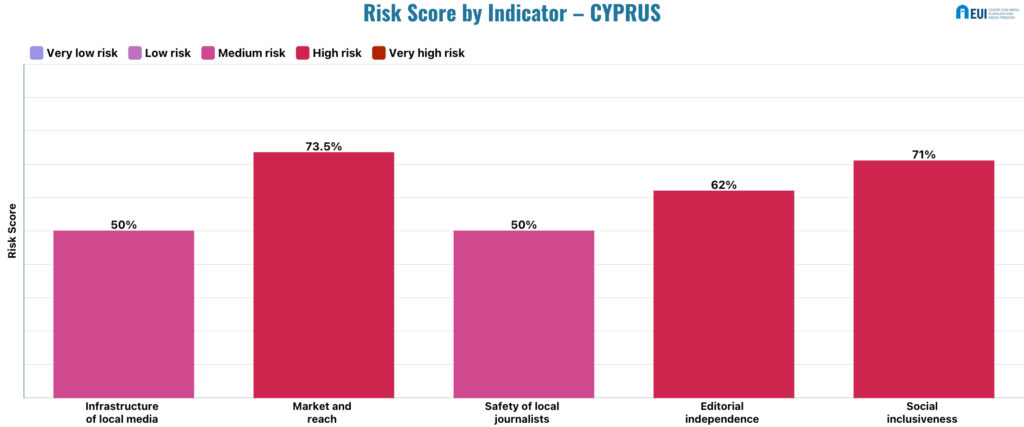

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (50%)

There is generally limited availability of local media except for what is online, which appears to have shown a relative increase over the past five years. However, due to the lack of metrics, there is no information on the reach they might have. Located in the main towns, these online media may not necessarily reach the population living in remote areas of the country. The geographical peculiarity and small size of Cyprus allow for national media (especially PSM) to provide news and topics about local and regional communities. This does compensate—to some degree—for the absence or incapacity of the local media sector to respond to existing needs; the overall score for the country is therefore judged at medium risk (50%).

Equally, given again the size of the country and the capacity of national media newsrooms to quickly address local issues and events (when necessary or when attractive from a newsworthiness perspective) it can be said that local communities are fairly well covered despite most local correspondents being stationed in the main cities. Their number has remained stable in recent years[1] and, considering expectations are low, this is considered to be a low risk in the case of Cyprus.

The same low risk finding applies for the PSM, the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation and the state-supported Cyprus News Agency, which maintain correspondents in each of the main cities.[2] Given that distances are small and the radius of coverage for their correspondents is fairly short, rural communities are served well when necessary.

[1] Interview with officials from the Cyprus Union of Journalists, 3/01/2024.

[2] ΚΥΠΕ., n.d.. https://www.cna.org.cy/about

Market and reach – High risk (73.5%)

As there is no data about local media revenues (except for local radio stations, which are overwhelmingly music related), given their limited role and marginal financial significance, it has not been possible to draw solid conclusions as to their market and reach or to identify trends. Based on an ad hoc research conducted by the authors of the present report, an increase in media outlets’ online presence can be discerned—however, crucially, there is no digital law in force which means that there is no public data available or public oversight mechanisms in place to assess Market and Reach of media online. Combined with the absence of any state support for local media in any form, including the absence of state advertising, this is an area that can literally be described as a dangerous information desert for the whole territory. Similarly, no local television channels or local press exist, except for some rare manifestations of weekly or monthly but mostly irregularly printed newspapers[1].

In terms of distribution there is just one press distribution agency in Cyprus, Kronos, which distributes 85% of the national (and local) press (and 100% of the international press) reaching 850 selling points (kiosks) on a daily basis with a fleet of around 60 vehicles. The agency reported that the volume of work has dropped significantly in the last 5 years[2], given the considerable—but undefinable—fall in circulation of newspapers and magazines, but could not provide details given restrictions imposed by publishers. It can be said that the supply distribution chain adequately meets the needs of the local media market in certain media sectors and the risk here is at medium level.

More relevantly, the government does not provide any financial support, and local media outlets can be said to operate within an unfavourable business environment. They cannot be considered to be viable in the long term. A de minimis scheme has been in place for the press since 2017[3] but does not cover local outlets. State advertising in local media is non-existent. As a result, the unavailability of sources of funding for the sector renders it at very high risk.

In terms of a community media sector—except within the confines of the education realm, i.e., at universities—Cyprus cannot be said to have one, and therefore no concept of a support system for it exists. As regards the viability of the local and community sector and the prospect of alternative ways of financing, given that national media are themselves struggling financially and their advertising support models are inadequate (just two have subscription models) the local sector cannot itself be deemed sustainable. The few online local media, which operate on a one to two journalist-based newsroom, are reliant on national news, copy-pasting from other news sources (usually by affiliation) and on adding the odd local story, local profile or local event to their output.

[1] Although many media are missing from the list published by the Press and Information Office, the following source offers a picture of the situation: Press and Information Office, “MEDIA/ NEWS AGENCIES LIST – PIO”, n.d., https://www.pio.gov.cy/en/media-list/.

[2] Information received from an unnamed source.

[3] A. Charalambous, “Additional €310,000 state financial support for island’s print media in 2022”, Philenews, 4 October 2022, https://in-cyprus.philenews.com/local/additional-e310000-state-financial-support-for-islands-print-media-in-2022/

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (50%)

There are no substantive issues with regard to the physical safety of journalists in Cyprus generally but in terms of safety of employment, journalists in small local media are susceptible to unfair treatment and changes in ownership.

An ad hoc survey by the authors of the report, has revealed that the number and size of local media in Cyprus are such that this research can only refer to a very limited number of journalists in total, even “one-person-shows” in some cases. It is considered that the operations of these tiny outlets are done through external collaborations and not necessarily within the context of a functioning newsroom. On issues of SLAPPs, for example, it could be said that local media are too small and insignificant in terms of reach and effect to be the target of SLAPPs but there is limited information available (this applies on a national level as well).

As to the risk of attacks and threats, including online, to the physical safety of journalists, this occurs rarely and there has been no increasing trend over recent years, despite one incident in 2021[1]. There is a legal framework in place to guarantee the prosecution of perpetrators of crimes against journalists, and it is generally effective, so the level of risk here is low. The Union of Cyprus Journalists is the only trade union representing journalists, both at national and local level.[2] It remains vocal and ever present, fighting a valiant battle, but risks are still deemed to be at medium level as it is only partially effective in guaranteeing editorial independence and/or respect for professional standards.

In terms of evaluating whether local journalists and newsrooms are committed in practice to independent, fair, impartial and accountable journalism, and adherence to codes of ethics or conduct, it must be repeated that the main online outlets are small and do not operate full newsrooms in the conventional sense. Although they do carry locally specific news, these newsrooms are heavily reliant on the main Cyprus News Agency and other international agencies (mainly Greek) with which they are affiliated for a large chunk of their output. Dependent too on advertorials and limited advertising revenues, which affect their overall professional standards, they are assessed at medium risk (50%).

[1] Gabriella, “Five people to appear before court in connection with attack against SIGMA TV”, Philenews, 19 July 2021, https://in-cyprus.philenews.com/local/five-people-to-appear-before-court-in-connection-with-attack-against-sigma-tv/

[2] See the Union of Cyprus Journalists’ website: Ένωση Συντακτών Κύπρου (ESK), ‘Ανακοινώσεις’ [announcements], https://esk.org.cy/

Editorial independence – High risk (62%)

In a heavily online reliant local media, the most significant feature in this section is the absence of a national digital media law, which impacts the context in which these currently operate. It follows that the owners of these small media units define and influence editorial content, which is likely to be skewed towards media proprietors’ businesses or other commercial interests. A major feature of local media of all forms is that much of their content is mere reproduction of news from other media.

It is important to highlight here that in July 2023 an amendment to the Law on Radio and Television Organisations abolished shareholding ceilings and other provisions on control /ownership, allowing the prospect of even one person (and potentially a politician, in office or not) controlling a media outlet as a shareholder. This allows also to control even many media outlets, through participation in the managing board of such outlets, provided the person does not own shares in the business[1]. While political control of media in general is regulated by the law on conflict of interest, making it incompatible to hold political office and be involved in other activities that present such a conflict, the specific provision is neither clear nor comprehensive. This new development, the amendment of the broadcasting law, therefore, renders the political control of local media by ruling parties, partisan groups or politicians as high risk.

Local media receive no state assistance in any form, not even advertising. State de minimis grants are only offered to dailies or weeklies, with specific criteria, and only to the existing press agency[2].

In terms of editorial content of local media being independent from commercial influence in practice this was deemed as high risk given that—as is the case on a national level— journalistic content is often blended with marketing, advertising and other commercial activities. Even when carrying locally specific news, the main online local outlets are small and may rely on bigger media for content.

The Cyprus Radio and Television Authority is the only existing regulatory body, limited to radio and television. The Authority’s licensing remit covers all outlets in an independent and relatively effective way. It is governed by the Law on Radio and Television Organisations 7(I)/1998 and Regulations Normative Administrative Acts (KDP) 10/2000, which provide guarantees of its independence; its decisions can be executed immediately, even when a recourse to Court overview is made. The Authority has no local branches, all its activities are centrally located. Jurisdiction on local radio stations is exercised independently and there was no evidence of any political interference or bias in any decision.

With regard to the PSM, the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, a regulation framework does exist and is in fact in the process of being updated— expected in 2024—but as things stand both when it comes to the appointment and dismissal of relevant governing board positions the government’s political influence is widespread, as is the board’s own editorial interference. When it comes to funding, the influence of the political establishment is also prominent; the political parties decide on the PSM’s budget on an annual basis. On the ground, the PSM has no local branches, operations are centralised in Nicosia with local correspondents in the main cities. The annual report of the Radio Television Authority about the PSM’s mandate as public service (defined narrowly in the law) finds little that is problematic, as it focuses mainly on metrics on information, culture and entertainment programmes and not on obligations to social, political and other groups in society or other issues[3].

[1] Law on Radio and Television Organisations L. 87(I)/2023 amending Law L. 7(I)/1998, https://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/arith/2023_1_087.pdf

[2] Ministry of Finance, Open call for participation to the 2023 scheme, https://mof.gov.cy/assets/modules/wnp/articles/202312/1524/docs/anoikti-prosklisi-ekdilosi-endiaferontos-2023.docx

[3] Cyprus Radio Television Authority, Quality Control Report on RIK for 2022, Nicosia, 2023, https://crta.org.cy/assets/uploads/pdfs/EKTHESI_RIK_2022_FINAL_compressed.pdf

Social inclusiveness – High risk (71%)

The PSM does provide news in minority languages but only for some languages, such as bulletins in English and Turkish on a daily basis. Its second TV channel RIK2 also carries news bulletins for the hearing-impaired and one of its radio stations provides news bulletins and other programmes in Turkish and Armenian[1]. But, ignoring the existence of minorities from forty different countries, representing approximately 20% of the population, can be seen as a considerable gap in the coverage of minorities. Minorities resulting from the wave of immigration over the last decade cannot be said to be represented in the PSM at all, and when they are referenced in the news, most of the time the coverage is biased and misleading. Migrants are rarely given a voice and the narratives that accompany reporting about them have mostly been those promoted by the government and its policy on immigration as well as by politicians in general. The same applies to communities of foreign national workers who are legally resident in Cyprus for work purposes.

The situation is worse when it comes to private media outlets. Here too when there is coverage it is mostly on the basis of stories that relate to national policy and difficulties in handling immigration or incidents involving migrants[2]. While the PSM is obliged and is expected to provide some coverage of recognised minorities[3], private media are not and, unlike the PSM, minorities are generally not represented in news reporting. When represented they are usually shown in a negative light (ghetto, crime, ill feeling by locals to increasing number of immigrants in their areas).

There are no specific outlets or channels addressing marginalised groups in Cyprus. Predictably, such groups maintain a strong presence on social media and only when exposure and publicity acquire traction on those platforms, does the matter spill over into other media (and even then, it is into national and not necessarily local media). The reverse side of the coin are telethons and radio marathons, which, according to organisers, aim at promoting the cause of specific communities (i.e., people with disabilities). The latter, however, according to their representatives denounce such events as following a patronising style that humiliates them.

In terms of whether local media provide sufficient public interest news to meet the critical information needs of the communities they serve, the situation warrants a high risk rating because of the number and location of local media, because the communities and the topics covered are very limited and because the content rarely meets CINs. It must, however, be said that there is no research on this topic. Equally, as there are no news media organisations in Cyprus experimenting with innovative responses to improve reach and audience, or any proposing new forms of work, journalistic products or services, or any discernible best practices in the sector, the risk is very high at 71%.

[1] Cyprus Radio Television Authority, 2023, pp. 20-21 and pp.38-39.

[2] “Συνελήφθη ο Σύρος που απειλούσε ότι θα μπει στα σπίτια κατοίκων” [Syros was arrested for threatening to enter residents’ homes], Pafos Press, 29 October 2023, https://pafospress.com/synelifthi-o-syros-poy-apeiloyse/

[3] Law on Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, Ch. 300A, https://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/enop/non-ind/0_300A/full.html

Best practices and open public sphere

Unfortunately, there are no examples of news media organisations in Cyprus experimenting with innovative responses to improve reach and audience, or proposing new forms of work, journalistic products or services. The fact that no study on the subject has ever been done is coupled with the lack of awareness on the importance of local media. However, there seem to exist various ‘communities’ that organise and communicate information on social media channels, either publicly or privately, but it is not possible to verify and assess this trend. Similarly, it was not possible to find any citizen or civil society initiatives providing innovative responses to tackle the problem posed by the decline of local and community news provision. Even in the case of print local media that also have online editions, there are no indications of exploiting the possibilities offered by digital technology.