Report authored by Maren Beaufort and Andreas Schulz-Tomancok, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

Context

Local and regional journalism has moved onto Austrians’ political agenda as relevant to democracy and as a locus of public connection[1] against the backdrop of digital transformation and changing democratic practices. In this project, news deserts are understood as areas where the citizens do not receive public interest information. According to this definition, Austria does not (yet) have to contend with the phenomenon of news deserts. Local and regional media cater to the rural, suburban, and urban areas; typically, with at least one daily newspaper, a number of local titles (print and online), several commercial private and non-commercial community broadcasters (radio and TV) and one regional studio of the PSM in each federal state. However, each region is characterised by a dominant media outlet, prominently represented in all sectors, which raises concerns about plurality, particularly when considering current funding practices and structural conditions.

Around two out of Austria`s nine million residents live in the capital Vienna, which is also one of the nine federal states. The other larger cities, with around 130,000 to 300,000 inhabitants, are the provincial capitals of Graz, Linz, Salzburg and Innsbruck. GRP per capita in the NUTS2 regions are below average in the east and south (with the exception of Vienna) and above average in the west. This coincides with regions of lower media coverage. Internet usage penetration is 94% with a less pronounced east/south-west gradient, while the download speed in rural regions is lower than in Vienna.[2]

The media are mainly a national responsibility. Notably there is no legal definition for “local media”, but one could refert to the legal guidelines for the allocation of subsidies.[3] It is common practice for regional media to refer to the federal provinces and local media to one or more municipalities or districts. The law[4] anchors community media as “non-profit” acting “in the local or regional area”.

There are currently no “local news deserts” in Austria that could be binary coloured mapped for the purpose and according to the definitions of this project. However, it was clearly revealed that major closures of local media outlets, which would lead to “news deserts” in several areas of Austria, are imminent in the medium term. An adequate response is needed: on the one hand by reorganising structural conditions (e.g. reducing concentration; supporting accountability) and on the other hand by transforming the funding logic towards journalistic quality and democratic relevance (in terms of content, proportionality and fair allocation rules), favouring also the local and regional media environment including smaller, innovative outlets.

[1] N. Couldry and T. Markham, Public connection through media consumption: between oversocialization and de-socialization? The Annals AAPSS, 608(1), 2006, p. 251-269.

[2] Statistik Austria: www.statistik.at; 94% average in 2022 ranging from 82% to 98% in the federal states

[3] www.rtr.at/medien/was_wir_tun/foerderungen/Startseite.de.html.

[4] KommAustria Act, §29. www.ris.bka.gv.at.

Main findings

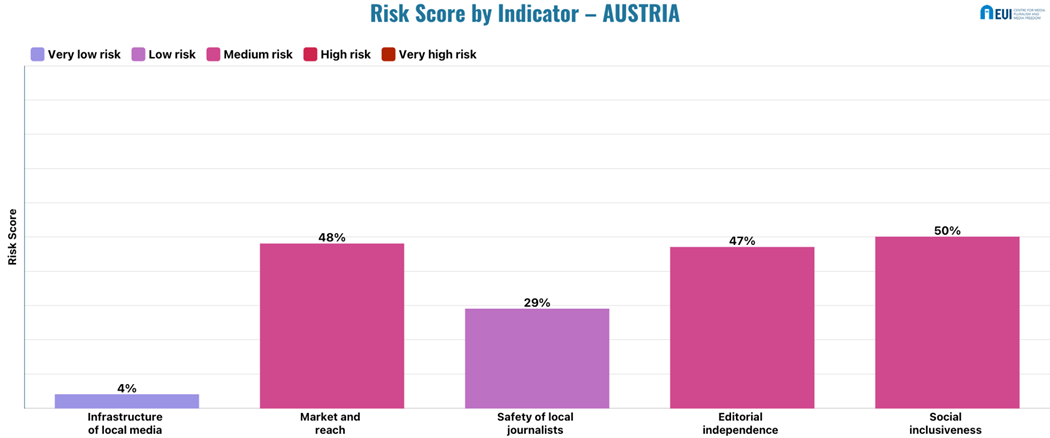

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Very low risk (4%)

In Austria, there is a historically grown, relatively dense and well-developed local and regional media landscape; the connection with the communities they serve is often close. There are differences between the provinces regarding coverage and reach as they are lower in the Eastern provinces than in the West of the country, with the exception of and partly because of the closeness to Vienna.[1]

TV-News are the main sources of information in Austria.[2] The regional PSM stations and their correspondents are located in the capitals of the nine provinces, recording top ratings in terms of reach and market share: ORF radio stations account for three in four of the radio minutes listened to.[3] Promoting national and regional identity is one focus of the PSM’s core mission, which is implemented through nine regional radio channels and regular regional TV-news.[4] Additionally, there are about 25 private TVs and 60 radio stations in the regional markets, showing typically significantly lower reach,[5] as well as 14 licensed community radios and three TV-stations (plus some online titles outside the Association of Community Media), seven of which are located in rural areas.[6] Their Cultural Broadcasting Archive became Austria’s largest podcast provider.

The dominant major media outlets produce dailies and cross-media content with a high regional reach of 40% up to over 60%, similar to the hundreds of mostly weekly local print and online titles.[7] Most of the latter prioritise entertainment or local events rather than news. Tabloids and free newspapers in Vienna achieve comparable reach,[8] while their clones attract large communities in the provinces. Daily newspaper supply in the Eastern provinces is dominated by Viennese titles, as its suburban regions are located in these surroundings.[9] In addition to a wide range of city newspapers and magazines, providing innovative multimedia contents, most nationwide media have their headquarters in Vienna, offering coverage on local issues. Compared internationally, regional journalistic online services are (still) underdeveloped, particularly regarding digital natives.[10] However, the print and broadcast legacy media operate websites and social media channels. Correspondents of the Austrian Press Agency (APA) are located in all provincial capitals.

[1] VÖZ, 2022, www.medienhandbuch.at.

[2] Reuters Digital News Report – Details for Austria 2020, 2023: https://digitalnewsreport.at.

[3] About 1.36 million daily viewers, and 2.1 million listeners daily on ORF regional TV & radio. ORF is obliged by law to operate broadcasting studios in all nine federal states.

[4] ORF Act, §§ 4, 3, 5, 31. Austrian parliament: www.parlament.gv.at/aktuelles/pk/jahr_2021/pk1320.

[5] VÖZ, 2022, www.medienhandbuch.at. Market entry of private broadcasters: mid 90s.

[6] www.freier-rundfunk.at. VFROE, 20 Jahre on air, 2018: Technical reach: 6,923,000.

[7] Media-Analyse, 2022, www.media-analyse.at. The Association of Regional Media in Austria represents around 240 regional newspapers.

[8] There are also nationwide quality newspapers that reach a percentage of the tabloids: 5%-11% in Vienna, 1%-5% in the regions. VÖZ, 2022, www.medienhandbuch.at.

[9] Media-Analyse, 2022, www.media-analyse.at.

[10] Kaltenbrunner et. al., Der Journalismus Report VII, 2022. This field is emerging.

Market and reach – Medium risk (48%)

Based on the available data, a mixed picture emerges regarding the financial situation of Austria`s local media sector. In recent years, the majority of media companies have seen their revenues decline, while others have recovered after a slump during the first year of the pandemic. In general, stagnating sales figures coupled with rising costs (distribution, paper price, etc.) have heightened economic pressures; certain politicians and audiences are also calling for austerity measures concerning PSM (in terms of structures and also referring to the regional stations). Although, there have not yet been significant closures in any of the sectors, a wave of closures is expected in the medium term.

Austria provides a wide range of media subsidies on the national level;[1] some of them are focused on regional diversity, others are available in particular for those who are not only of local interest and are distributed in more than one federal state. Funding from the federal states is rather low and indirect subsidy means tax reduction in Austria. Subsidies for all media sectors increased from around 37 million euro in 2018 to 124 million euro in 2023 (state advertising from 170 million euro to 200 million euro, while the provinces (-9%) and the national government (-38%) reduced payments in 2023). The top 20 beneficiaries include regional players as well as the Association of Community Media.[2] State subsidies are typically distributed transparently but not fairly, because the funding logic does not support journalistic quality and democratic relevance (in terms of content, proportionality and fair allocation rules), it rather favours large legacy media with high reach or circulation, while small, innovative outlets are not supported sufficiently. This is also true for the new well-endowed fund to promote digital transformation, as digital natives cannot apply and the funding rate is 50%. This practice encourages mergers: regional publishing houses currently operate—after highly complex joint ventures—in an increasingly concentrated form and with constantly changing business models. Four of them hold a total market share of around 16%, and over 70% in the regional market.[3]

The market share of the largest private TV-broadcaster is 4.3%,[4] while the PSM holds more than one-third of the TV-market. ORF’s total radio market share is about 75% (PSM regional radios: 35%); the one of the private commercial radios is about 25%. According to the “Radiotest” slight losses or stagnation in reach occurred in recent years, with some exceptions.[5] More than 60% of the PSM is financed by programme fees, replaced by a household levy from 2024. In addition, the ORF finances itself with advertising and other sales.[6] Commercial broadcasting is financed by advertising and funding, recording stagnating or declining advertising revenues that, according to VOEP[7] are rather flowing to international online platforms. Compared to the ORF, the Commercial Broadcasting Fund corresponds to around 3%.Experts consider this to be sufficient, as long as “the journalistic output of local private-commercial media tends to focus on entertainment rather than local information, culture or identity.”[8] The leeway of private commercial media is large, when contrasted with that of community media: They receive significantly lower funds (one quarter) and lack advertising revenues as they are by definition “non-commercial”. Nevertheless, the Non-Commercial Broadcasting Fund has recently been substantially increased[9] and community media also benefit from EU-funding or other funds (for minorities, digital transformation, etc.). Still, without many volunteers, non-profit community broadcasting would not be able to fulfil their democratic role for economic reasons.

Austria’s local and regional print titles are mainly distributed by subscriptions or advertising-financed free content to all households. The number of sales outlets (“Trafiken”) has declined sharply.[10] Instead, the postal service monopoly acquired a crucial structural role as well as increasing costs for distribution. The current recovery trend has not yet reached pre-pandemic levels[11] and the reach of regional print titles is dropping.

Particularly small, innovative digital natives face poor funding conditions. According to the available data the reach of larger regional platforms and of PSM`s orf.at increases (from 55.6% in 2018 to almost 70% in 2022).[12] The wider use of paywalls for online content coincide with increasing willingness to pay (at least for digital services of regional legacy media that is considered trustworthy).[13]

[1] www.rtr.at/medien/was_wir_tun/foerderungen/Startseite.de.html.

[2] Community Media only in the case of subsidies. Calculations based on: www.medien-transparenz.at.

[3] Calculations based on access-restricted data provided by H. Fidler, https://diemedien.at.

[4] 4.3% Servus TV; all national private TV-stations together hold around 10%.

[5] Daily reach 2018 to 2022. Calculations based on access-restricted data provided by H. Fidler, 2022, https://diemedien.at/ VÖZ, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, www.medienhandbuch.at.

[6] In general, there are restrictions, while regional ORF-stations are allowed for their own advertising activities. ORF, 2023, https://der.orf.at.

[7] Managing director of the Association of Private Broadcasters Drumm, 15.06. 2023 (email); while radio marketer RMS Austria reported a steady increase in revenues.

[8] Expert Medienhaus Wien Kaltenbrunner, 16.06.2023 (in-person).

[9] From three to five million Euro annually from 2022.

[10] NÖN, A. Kiefer, 2018, www.noen.at/niederoesterreich/politik/trafiken-sterben-der-kampf-ums-ueberleben-trafiken-sterben-josef-prirschl-85996825

[11] No data access, information by Dir. of Association of Regional Media Henrich, 13.08.2023 (zoom-call).

[12] Calculations based on VÖZ, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, www.medienhandbuch.at; Media-Analyse, 2022, www.media-analyse.at.

[13] From 9,1% in 2019 to 13.5% in 2022. Own calculation based on Reuters Digital News Report – Details for Austria 2020, 2023, https://digitalnewsreport.at.

Safety of local journalists – Low risk (29%)

The journalistic centre of the country is Vienna, where about 56% of all full-time journalists live and work. One third of all (about 5350) Austrian journalists are salaried local journalists, plus around 20% freelancers (Kaltenbrunner et. al., Der Journalismus Report VII, 2022). Access to the journalistic profession is open, i.e. there are no legally mandatory educational requirements. While the average age is increasing, local journalists are sometimes very young, with significantly more part-time contracts for women. The salary of local journalists is below the nationwide average;[1] many freelancers practise journalism as a sideline (and little is known about the conditions and social protection, although legislation guarantees minimum wages) and regarding community media, most contributors are voluntaries.

Perceived job security decreases as technological change, the pandemic and distrust of journalism in general are causing uncertainty.[2] Although independent journalism and the safety of journalists is advocated by professional associations[3] and the Austrian Press Council, the boundaries between sales and editing are difficult to keep, especially in small (local) editorial offices. While attacks on physical safety decreased, there have been more verbal threats online.[4] Of the 16 SLAPP-lawsuits since 2010[5] only two were against local media.[6]

[1] Average salary of Austrian journalists: 3,800 Euro (gross); average Austrian employee: 2,400 Euro.

[2] Union of Private Employees-Printing, Journalism, Paper Wolf, 16.06.2023 (in-person); Kaltenbrunner et. al., Der Journalismus Report VII, 2022; T. Hanitzsch, J. Seethaler and V. Wyss, Journalism in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, 2019, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-658-27910-3

[3] Professional associations do have regional representations but suffer from a decline in members

[4] J. Seethaler, M. Beaufort and A. Schulz-Tomancok, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Austria, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75714; no detailed data for the local market

[5] SLAPPs in Europe (CASE): www.the-case.eu/slapps.

[6] European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, 2022, www.mappingmediafreedom.org/#/; Council of Europe, Safety of Journalists Platform,https://fom.coe.int/pays/detail/11709480.

Editorial Independence – Medium risk (47%)

Regarding the audio-visual and radio sector, none of the outlets is owned or controlled by governmental actors. While no legislation in place supplies provisions related to controlling media by politically affiliated actors (with the exception of PSM), legal entities under public law and political parties are precluded from providing broadcasting.[1] Community media are legally part of “private broadcasting” and according to their charter they are independent from influencing actors. The ORF Act (theoretically tries, but) in practice fails to guarantee independence from political influence at the national as well as at the regional level, which is partly about the rules that enable the government to appoint at least a simple majority of the Foundation Council, sufficient for most of its decisions. This “politics-in-broadcasting system” engenders politically motivated entanglements. The weight of the regional directors is remarkable: “Anyone who wants to become head of ORF needs the federal states.”[2] In the print sector, no legislation regulates ownership matters regarding their entanglement with the political realm. Yet, there seem to be close ties between certain newspapers and political parties,[3] which has led to several resignations of politicians (including the Federal Chancellor). The situation at the regional level can only be surmised. The number of digital native media with a more or less transparent closeness to political actors is growing, like a revival of the “media-party parallelism”, typical of democratic-corporatist countries,[4] but without adequate awareness of the influencing potential. There is only one big news agency in Austria whose statutes commit it to political independence.

In terms of state advertising, all political actors are obliged to disclose their media collaborations fully,[5] but the law does not prevent preferential treatment, so that supporting the largest tabloids in the country has become an issue.

As only broadcasters are obliged to have editorial statutes, professional associations and the Austrian Press Council are essential in advocating professional standards. The latter, however, may only include print titles, their online platforms, news agencies and community media and its Code of Ethics focuses on economic influence. Several local outlets are committed voluntarily to the Council’s Code, but there are no general standards binding all Austrian journalists and the given sanctioning powers are weak. Cases of commercial influence in the advertising-financed processes are reported on the local level. There are no local branches of the media authority, however, it works independently, and its sanctioning powers are usually considered as effective.[6] But in general, accountability mechanisms at all levels—industry, sector, and company—are underdeveloped, as recent incidents have shown.

Regarding content diversity there are no comprehensive analyses considering the local market. Only one regional print title, highly relevant in two federal states, was analysed recently[7] with the outcome that it devotes significantly more attention to the governing parties than to the parliamentary opposition, while NGOs receive less attention than state actors. Women have a representation of 13%, similar to national Austrian media. These results are consistent with an audience study concerning suspected political independence of the PSM stating that 53% of Austrians doubt that ORF’s regional studios can report freely and without political pressure.[8]

[1] J. Seethaler, M. Beaufort and A. Schulz-Tomancok, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Austria, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75714; ORF Act, Private Radio Broadcasting Act and AVMD (exceptions): www.ris.bka.gv.at.

[2] Der Standard, 2022, www.derstandard.at/story/2000141979899.

[3] Like the high-circulation tabloid Oesterreich and the quality paper Die Presse, as exposed by some details of the Economic and Corruption Prosecutor’s Office’s corruption investigations.

[4] D. C. Hallin and P. Mancini, Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge university press, 2004.

[5] Media Transparency Law, www.ris.bka.gv.at. In the past (until 2023), crucial restrictions have resulted in up to half of state advertising not transparent.

[6] KommAustria Act, §6, and Art 20 (2) 5a B-VG as amended by BGBl. I 50/2010, www.ris.bka.gv.at.

[7] Kleine Zeitung (Styria Media Group for Styria and Carinthia); M. Beaufort, Media in democracy – Democracy in the media, 2020, https://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/handle/ediss/8998.

[8] Market Institute Linz/Der Standard, 2023, derstandard.at/story/2000142255876/. Additional results: 45% of Austrians think: “Regional politics has too much influence on the ORF regional studio in my province” (29% disagree); 43% miss critical statements in ORF’s regional news, for example, from opposition politicians (34% don’t).

Social Inclusiveness – Medium risk (50%)

Local journalists’ professional self-conception not only keeps them in close contact with their audience, they aim to monitor and inform the widest possible audience in the region as well as to point out grievances. Clearly important is “giving `ordinary people` a voice” and “standing up for the disadvantaged”, indicating that advocacy journalism is aspired to more strongly than among the entirety of Austrian journalists.[1]

Nevertheless a study assessing the regional studios of the PSM found that despite a large market share, 45% of Austrians in all provinces think that the “ORF’s regional news always focus on the same people.”[2] In contrast, non-profit community media act locally and inclusively through rich participation and are by definition deeply engaged with their audiences, describing their democratically relevant characteristics in their charter.[3] Aiming on building modern societal and educational media centres, becoming—also physically—forums of inclusive regional togetherness, they are able to develop local discourses that lack attention in the classical media environment. Therefore, the relatively low reach is not the most relevant value when it comes to community media, but the multiplier effect created by the activities in and for a region.

Applying to the entire Austrian audience and its comprehensive information diets, a recent study revealed that news users have distinct expectations of democratic news performance to satisfy their critical information needs.[4] A comparison of these expectations with the actual news supply in terms of contents showed that especially people who have a participatory understanding of democracy (and thus about one third of the population) do not sufficiently find what they need in Austria’s news supply.

Many small newspapers, magazines, blogs and websites address marginalised groups, as well as some prominent outlets, which is either relatively new or niche. Non-profit community media integrate a wide range of minorities into their activities and operate through 41 languages. The PSM is obliged to provide linguistic diversity and representation only regarding the six Austrian legally recognised minorities.[5] Additionally, a few English and French-language programmes are available. Giving access for persons with disabilities is mandatory to ORF; even private broadcasters have recently been tasked to improve accessibility, but often start at zero (like with minorities).[6] Because, in the past, the legal provisions were formulated in a non-binding and hardly measurable way,[7] the overall DARE[8] only rated 67.5%. However, a recent report notes positive developments in Austria, although there are still gaps in the implementation.[9] Finally, there is a relatively hidden migrant mass media market. Unofficially recognised minority groups are also eligible for media production and occupy a significant part of this market, without governmental support.[10]

[1] 84% of local journalists (vs. 78% of the entirety of Austrian journalists) resp. 83% (vs. 62%). Kaltenbrunner et. al., Der Journalismus Report VII, 2022.

[2] Market Institute Linz/Der Standard, 2023: derstandard.at/story/2000142255876.

[3] Charta of Austria Community Broadcasters: www.freier-rundfunk.at.

[4] Namely according to users` personal notions of democracy. M. Beaufort,Media in democracy – Democracy in the media, 2020, https://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/handle/ediss/8998; J. Seethaler and M. Beaufort, Community media and broadcast journalism in Austria: Legal and funding provisions as indicators for the perception of the media societal roles, The Radio Journal, 2017.

[5] Croats, Slovenians, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovakians, Roma. ORF Act, §4: www.ris.bka.gv.at. During the pandemic there were special activities in many languages.

[6] ORF Act, §5; AVMD, § 30: www.ris.bka.gv.at.

[7] E.g. “economic reasonableness” (ORF Act); “gradual improvement of accessibility” (Audiovisual Media Services Act)

[8] DARE (Digital Accessibility Rights Evaluation) index

[9] J. Seethaler, M. Beaufort and A. Schulz-Tomancok, Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Austria, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75714.

[10] Y. Andakulova, Minority Media in Austria: Case Study Analysis of the Status Quo of Linguistic Diversity in the Austrian Media Landscape, Global Media Journal, 2023.

Best practices and open public sphere

A small range of innovative concepts can be found at all levels of the journalistic process. Some projects focus on diversity and inclusion (text-to-speech, etc.) or develop integrative and participatory concepts (e.g. citizen participation, collaborative investigative journalism), others are concerned using new business models (paywalls, user loyalty, etc.). Recently, highly endowed funds were created that provide space for innovation, as they are not tied to content or specific sales models,[1] albeit they are primarily available to sizable legacy media. Thus, local journalism is using its potential, as examples from large regional players and some smaller projects show, but a change in funding logic and innovative financing (such as crowdfunding) could bring more innovation.

[1] See for details www.rtr.at.