By Jan Erik Kermer

In this blog post I explore the ongoing challenges journalists face from state surveillance and how Article 4 marks a significant milestone in addressing this issue. I also touch upon some of the provision’s potential shortcomings including the risk that member states may exploit loopholes to continue deploying surveillance technologies on journalists, ultimately creating a chilling effect on their sources . Lastly, I lay out some of the key changes for the upcoming implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM2025) on the question of state surveillance.

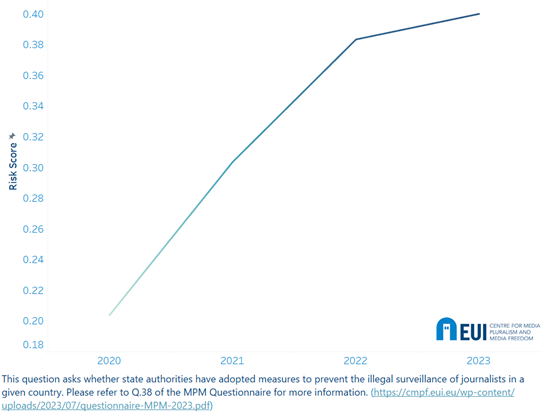

The surveillance of journalists is rife across much of the globe and Europe is, by no means, immune to this problem. According to data from the Media Pluralism Monitor, the situation in Europe has deteriorated significantly in recent years, with the risk level increasing by over 20% since 2020 (see Fig.1 below). Article 4 of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), therefore, represents a crucial, timely and unprecedented provision, signalling the European Union’s bold commitment to establishing a common legal framework to address the increasing usage of sophisticated technologies, which pose not only a serious threat to journalistic sources but privacy in general.

Fig.1 – Trends in monitoring of state surveillance: Aggregate risk scores for EU-27 and candidate countries over time

What are intrusive surveillance technologies?

Intrusive surveillance technology refers to “any product with digital elements specially designed to exploit vulnerabilities in other products with digital elements that enables the covert surveillance of natural or legal persons by monitoring, extracting, collecting or analysing data from such products or from the natural or legal persons using such products, including in an indiscriminate manner” (Article 2(20) of EMFA). Surveillance technologies include Deep Packet Inspection (see Fuchs, 2013 for more), geolocation tracking, facial recognition and other AI-enhanced surveillance tools, with Spyware being one of the most invasive and pervasive surveillance technologies.

In simple terms, spyware is a type of malware that spies on a users’ activities without their knowledge or consent. Spyware “secretly record[s] calls or otherwise use the microphone of an end-user device, film or photograph natural persons, machines or their surroundings, copy messages, access encrypted content data, track browsing activity, track geolocation or collect other sensor data, or track activities across multiple end-user devices” (Recital 25 of EMFA).

The ongoing battle with state surveillance of journalists…

The use of surveillance tools by states on journalists remains a widespread practice afflicting countries worldwide. Jamal Khashoggi (Saudi Arabia), Javier Valdez Cárdenas (Mexico), Omar Radi (Morocco) and Maati Monjib (Morocco) are prominent examples of a global phenomenon (Woodhams, 2021). However, the European continent is not immune from this practice, as documented by several recent cases. In 2021, Greek journalists, Stavros Malichudis and Thanasis Koukakis were allegedly targeted with Predator spyware by the Greek state agency, the National Intelligence Service (EYP). Alarmingly, this phenomenon shows no signs of abating, with several cases reported last year. In 2023, two Prague-based Russian journalists, Alesya and Irina Marokhovskaya, were allegedly subjected to surveillance from Russian state agencies (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2023). In the same year, the Russian independent media outlet, Meduza (Latvia) had allegedly been affected with Pegasus software, though the perpetrator has yet to be identified (Access Now, 2023).

The findings from the Media Pluralism Monitor paint a rather bleak picture, with researchers reporting that several member states are employing spyware to snoop on journalists (Bátorfy et al., 2022; Štětka et al., 2024; Rožukalne and Skulte, 2024). Amnesty International’s “Predator files” (2023) also offers a critical assessment concluding that the EU had failed to adequately regulate spyware and uphold human rights standards (Phillips, 2023). The same report also highlights the inadequacies in preexisting EU legislation including the lack of due diligence and government oversight when distributing these technologies, despite export regulations such as the Dual-Use Regulation (2021/821) being in place (Phillips, 2023).

Article 4 in a nutshell: an unprecedented step forward in protecting journalistic sources

In view of these longstanding issues, Article 4 of EMFA represents a timely and crucial piece of legislation. In essence, Article 4 aims to safeguard journalistic sources by banning state authorities from deploying these aforementioned surveillance tools on journalists, save for exceptional circumstances. The first two paragraphs lay out the overarching principles underpinning this article: (1) Journalists should be free to carry out their activities without interference (Para.1) and (2) there is an explicit commitment to protecting journalistic sources (Para.2).

The sub-paragraphs of Paragraph 3 contain the nitty-gritty of the article, delineating the surveillance practices that are prohibited. In short, member states are prohibited from:

- Requiring media service providers to disclose sources (Para. 3a);

- Detaining, sanctioning, intercepting, surveiling or searching media service providers (Para. 3b); and,

- Deploying surveillance software on media service providers’ devices (Para. 3c).

Paragraphs 4 and 5 detail the provision’s derogations, outlining the specific circumstances under which state surveillance may be allowed. This includes the requirement for ex-ante judicial authorisation, which provides an important additional layer of protection for journalistic sources, although this protection is somewhat watered down by leaving the door open to ex-post authorisation in “duly justified exceptional and urgent cases” (Para.4). In addition, intrusive surveillance software may be deployed for investigating specific offences listed in Article 2(2) of Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA, or for “serious crimes” as defined by national law (Para.5), which exposes it to the risk of regulatory fragmentation. Paragraph 6 requires regular judicial review of state surveillance measures to ensure the conditions justifying their use continue to be met. Paragraph 7 cites Directive (EU) 2016/680, which governs the processing of personal data by law enforcement authorities. Paragraph 8 ensures the right to an effective remedy and a fair trial – citing Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU.

National security derogation reintroduced via the backdoor?

Although Article 4 represents an important step in shielding journalists from the prying eyes of the state, there are certain aspects that could benefit from further clarification to ensure its effectiveness in protecting journalists. For instance, while explicit reference to the national security derogation has been removed from the final provision, MEPs have raised legitimate concerns that it has merely been reintroduced through the backdoor. Paragraph 9 states that “the Member States’ responsibilities as laid down in the Treaty of the European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union are respected”. This is reaffirmed in Recital 8 of EMFA which states that “this Regulation respects the Member States’ responsibilities as referred to in Article 4(2) of the Treaty on European Union, in particular their powers to safeguard essential state functions.” As Article 4(2) makes plain, these “essential state functions” include safeguarding national security which “remains the sole responsibility of each Member State”. This addition potentially opens the door for member states to continue deploying surveillance technology on journalists under the guise of national security (EDRi, 2023; PEGA Committee, 2023).

In addition, Para.4c states that member states can deploy intrusive surveillance tools “by an overriding reason of public interest”—this includes grounds related to public policy, public security, public safety, and public health (the so-called ‘ORPI’ principle). This begs the question what distinguishes national security from the grounds contained in ORPI—a distinction that EU jurisprudence has seemingly yet to clarify (EDRi, 2023). Tellingly, the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights defines national security as “major threats to public safety and including cyber-attacks on critical infrastructures” (EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017:53, emphasis added).

What about preventing the outsourcing of surveillance to private entities?

Another important consideration is that this article does not appear to address the issue of outsourcing surveillance to private entities. The European Parliament’s proposed amendments were more watertight in this regard with the range of actors expected to comply with Article 4 extending to “Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies and private entities” (Amendment No. 105 and 106 related to Article 4.2.a). Article 4, as per the European Parliament’s proposed amendments, furthermore, would have prohibited commissioning a third party to deploy spyware, preventing member states from delegating the use of spyware to private companies. This was reaffirmed in the detailed list of derogations pertaining to Article 4.2a which state that “Member States, including their national regulatory authorities and bodies, Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies and private entities shall not retrieve data related to the professional activity of media service providers and their employees, in particular data which offer access to journalistic sources”.

It would appear that the final text does not cover instances in which national governments delegate the deployment of spyware to non-state actors. In such cases, while the state would not be deploying spyware directly, it would still pose a risk to journalistic sources via indirect channels (Brogi et al.,2023:50). In fact, outsourcing certain tasks by states to private entities already seems to be a common practice. According to the Center for International Media Assistance Report, the private surveillance industry is booming, with states turning to the private sector to purchase off-the-shelf surveillance tools, avoiding the need to invest in developing such technology themselves (Woodhams, 2021:5). Indeed, in the context of disinformation, it is, alas, common knowledge that regimes not only fund disinformation campaigns but outsource them to private so-called “troll farms” (Euractiv, 2024). These circumstances are an important and pertinent reminder that while the state might not be engaging directly in disseminating disinformation, it does so indirectly, by delegating these “dirty deeds” to public, semi-private or commercial entities (Brogi et al., 2023:50) .

MPM2025: Raising the Bar in State Surveillance Monitoring

In light of these considerations, the Media Pluralism Monitor has established a higher standard in monitoring state surveillance. In carrying out the assessment of state surveillance in each country, researchers are required to consider not only surveillance practices by state authorities, but also the outsourcing of surveillance to private entities and quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations (so-called quangos). In addition, taking inspiration from Article 4 of EMFA, this question is now framed to consider “intrusive surveillance technologies” more broadly rather than focusing solely on spyware, which is just one form of such technology. Indeed, surveillance is about much more than just spyware, and, as pointed out earlier, there are a myriad of surveillance tools available such as Deep Packet Inspection (DPI), geolocation tracking, biometric/facial recognition and other AI-enhanced surveillance tools. Therefore, employing the catch-all term of surveillance technology acknowledges that not all methods of covert surveillance involve spyware, with these technologies evolving rapidly.

Final remarks

Wrapping up, Article 4 of EMFA undoubtedly marks an important milestone in protecting journalists from state surveillance, being the first-ever regulation to address this increasingly pervasive issue. The provision represents a crucial step forward in outlawing a range of state surveillance practices and including judicial oversight for their deployment in exceptional circumstances. That said, there is still room for further clarification in the provision’s interpretation to ensure it delivers on its overarching goal of protecting journalistic sources. In particular, there are lingering doubts that the national security derogation has merely been reintroduced via the backdoor by referencing Article 4(2) of the Treaty on the European Union. Additionally, it is not entirely clear whether this provision covers the outsourcing of surveillance to private entities. Therefore, in order to make the law more watertight against abuse of journalists’ rights, ultimately protecting journalistic sources, it is essential that any interpretation of Article 4 categorically excludes national security as a legitimate derogation and the law is interpreted broadly to encompass private entities within its remit.

For a more in-depth analysis of this provision, readers are invited to check out the working paper in full which you can find here.

References

Access Now. (2023, September 13). Hacking Meduza: Pegasus spyware used to target Putin’s critic. https://www.accessnow.org/publication/hacking-meduza-pegasus-spyware-used-to-target-putins-critic/

Bátorfy, A, Bleyer-Simon, K, Szabó, K, Galambosi, E (2022). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Türkiye in the year 2021. Country report : Hungary. Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM), Country Reports – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/74692

Brogi, E., Borges, D., Carlini, R., Nenadic, I., Bleyer-Simon, K., Kermer, J. E, Reviglio Della Venaria, U., Trevisan, M., & Verza, S. (2023). The European Media Freedom Act: Media freedom, freedom of expression and pluralism. European Parliament, Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Study PE 747.930. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/75938 . Retrieved from Cadmus, EUI Research Repository.

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2023, September 22). Two Prague-based Russian journalists threatened, fear surveillance. https://cpj.org/2023/09/two-prague-based-russian-journalists-threatened-fear-surveillance/

Euractiv. (2024, March 14). EU Parliament passes European Media Freedom Act, concerns over spyware remain. www.euractiv.com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/media/news/eu-parliament-passes-european-media-freedom-act-concerns-over-spyware-remain/

European Digital Rights (EDRi). (2023, October 3). Encryption in the age of surveillance – European Digital Rights (EDRi). https://edri.org/our-work/event-summary-encryption-in-the-age-of-surveillance/

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2017) ‘Surveillance by intelligence services: Fundamental rights safeguards and remedies in the EU. Volume II: Field perspectives and legal update’, Publications Office of the European Union, at: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2017-surveillance-intelligence-servicesvol-2_en.pdf

Fuchs, C. (2013). Societal and ideological impacts of deep packet inspection internet surveillance. Information, Communication & Society, 16(8), 1328–1359. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.770544

Kermer, J.E, ‘ Article 4 of the European Media Freedom Act : a missed opportunity? : assessing its shortcomings in protecting journalistic sources’, in Simeonov, K., and Yurukova, M. (eds), Papers from the Eleventh International Scientific Conference of the European Studies Department : the agenda of the new EU institutional cycle, Sofia : Minerva, 2024, pp. 192-207[Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF)] – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/77470

PEGA Committee. (2023). The impact of Pegasus on fundamental rights and democratic processes (Study). European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/740514/IPOL_STU(2022)740514_EN.pdf

Phillips, R. (2023). The Efficacy of European Union Spyware Regulations. Virginia Tech. Tech Humanity Lab. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/7ddfc7ac-400f-4690-8e52-cffec44dbc5b/content

Rožukalne, A., & Skulte, I. (2024). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: Application of the media pluralism monitor in the European member states and in candidate countries in 2023. Country report: Latvia. Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), EUI, RSC. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/77007

Štětka, V., Adamčíková, J., & Sybera, A. (2024). *Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: Application of the media pluralism monitor in the European member states and in candidate countries in 2023. Country report: The Czech Republic*. Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), EUI, RSC. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/77020

Woodhams, S. (2021). Spyware: An unregulated and escalating threat to independent media. Center for International Media Assistance. https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CIMA_Spyware-Report_web_150ppi.pdf