Written by Roberta Carlini and Pier Luigi Parcu

In this blogpost we analyse article 22 of the European Media Freedom Act, which introduces the so-called “media plurality test” in the assessment of media market concentrations. After arguing the rationale of the new provision, we analyse its design, focusing on the scope and the criteria of the media plurality test. In particular, we highlight the partial inclusion of online platforms in the scope of the provision, and the possibility to consider structural safeguards to media pluralism and editorial independence as a decisive condition for the approval of a defensive merger.

Article 22 of the EMFA marks the coronation of at least three decades of attempts by the European union institutions to address the issue of concentration of media ownership. The main rationale for a specific assessment of the mergers involving the media, separate from the mergers evaluation under the competition law, lies in the specificity of the media sector, whose contribution to the well-functioning of a democratic society involves dimensions that go beyond the pure economic rationale, including political, cultural and social considerations.

The role of the media as primary actors in the public sphere, as famously theorised by Jurgen Habermas (1989) and the value of an egalitarian distribution of communicative power in the democratic process, as argued in the seminal work of Edwin Baker (2007), imply that plurality and diversity of media offer should be pursued as a value, and concentration of opinion power should be addressed as a menace in itself, regardless of actual abuse of market power. This normative approach evolved in the XX century, in parallel with the evolution of the media markets, particularly in the audiovisual sectors, characterised by structural tendencies toward concentration. The rationale for specific anti-concentration rules in the media sectors is even stronger with the digital transformation, which brought new threats to media pluralism. Platforms have increased the opportunities to disseminate and access media content, but also intensified the tendency towards concentration in the traditional media sector in response to the extreme market power of few actors in the digital sphere (Doyle 2016; Schlosberg 2017).

At the national level, the legal framework on media ownership concentration is diversified and fragmented. As highlighted by the mapping of the Study on media plurality and diversity online, only half of the member states have special rules to evaluate media mergers, employing different methods and criteria (furthermore, the protection of media pluralism is not always considered among the criteria). The fragmentation of national rules is also problematic for their potential use to pursue goals and protect interests other than media pluralism; and for the obstacles that a fragmented legal framework poses to the common media market.

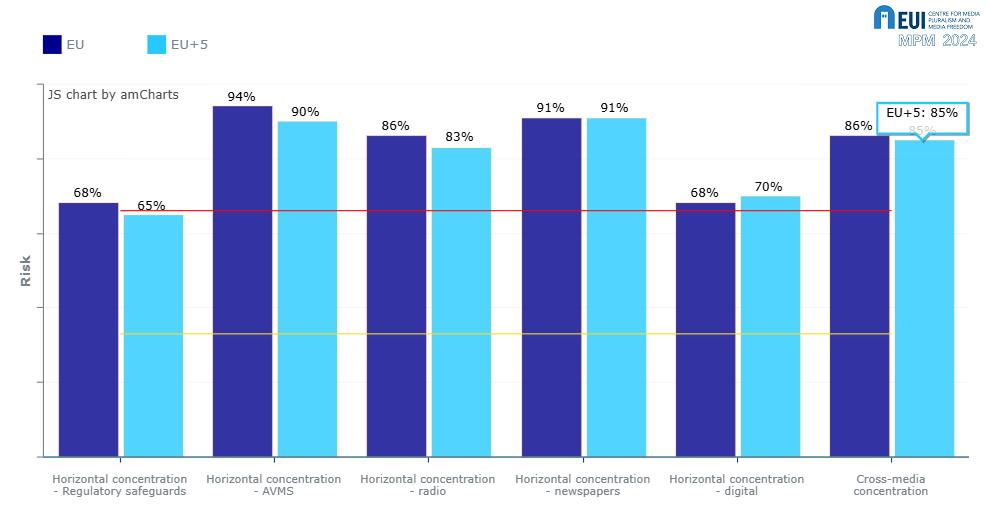

In addition, it is worth noting the lack of effectiveness of the national anti-concentration rules. The Media Pluralism Monitor results for the indicator that measures risks related to media ownership concentration have consistently shown a high risk since the beginning of the exercise; even in countries where the regulatory framework tries to limit horizontal and cross-media concentration, the economic indicators reveal a high level of actual market concentration.

Figure 1. MPM 2024, Plurality of media providers – averages per sub-indicator

In recent years, the high level of risk for concentration went hand in hand with a growing level of risks for the economic sustainability of the media.

These trends lead to two possible explanations: on the one hand, high levels of concentration did not help traditional media to remain competitive in the digital environment; on the other hand, the worsening economic conditions triggered a new wave of media concentration, motivated as defensive mergers to face digital competition (Carlini et al. 2024). This creates an unavoidable tension between safeguarding a pluralistic media landscape — characterised by dispersed ownership — and ensuring the economic sustainability of the media.

The scope of the media plurality test

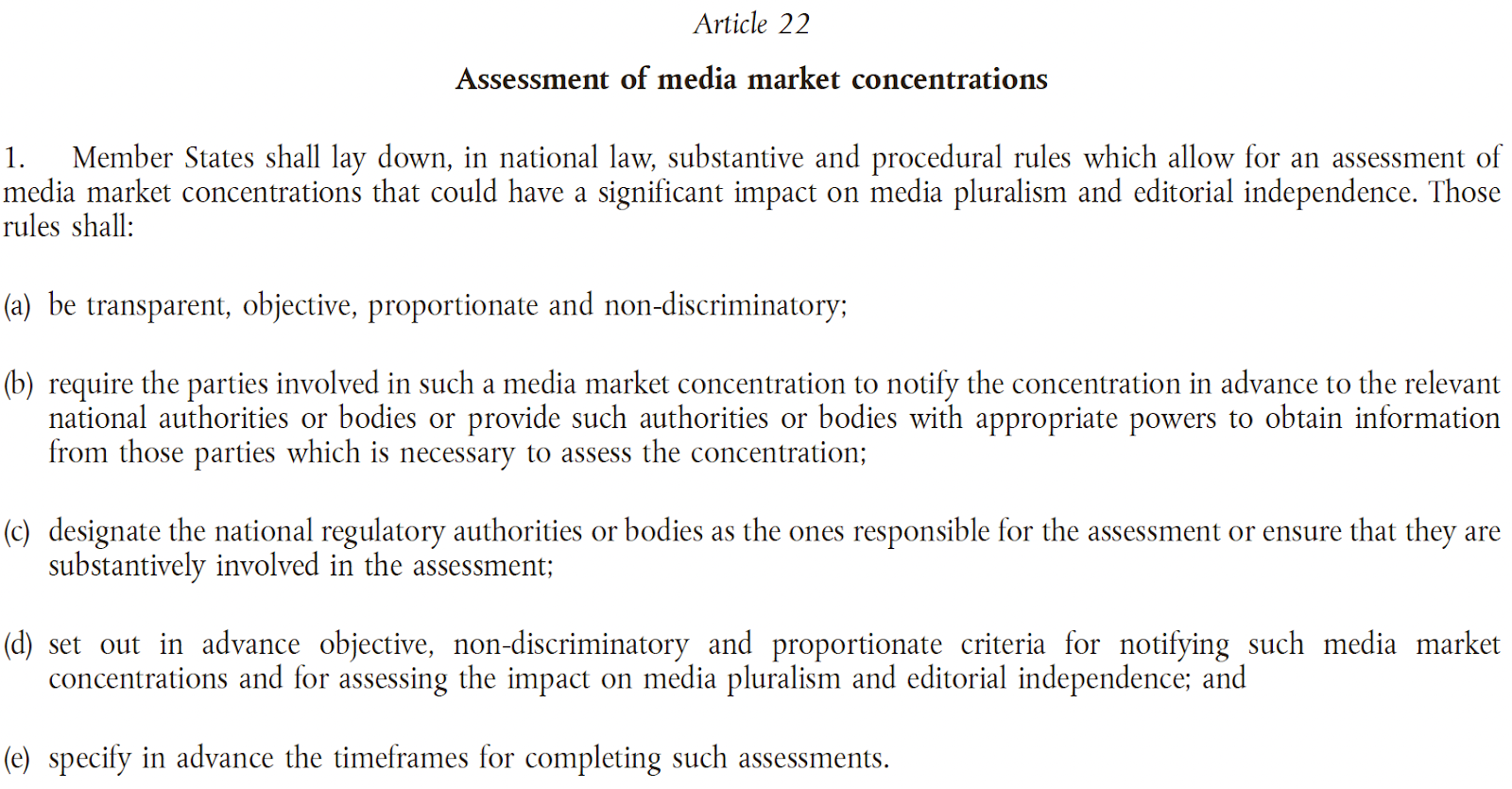

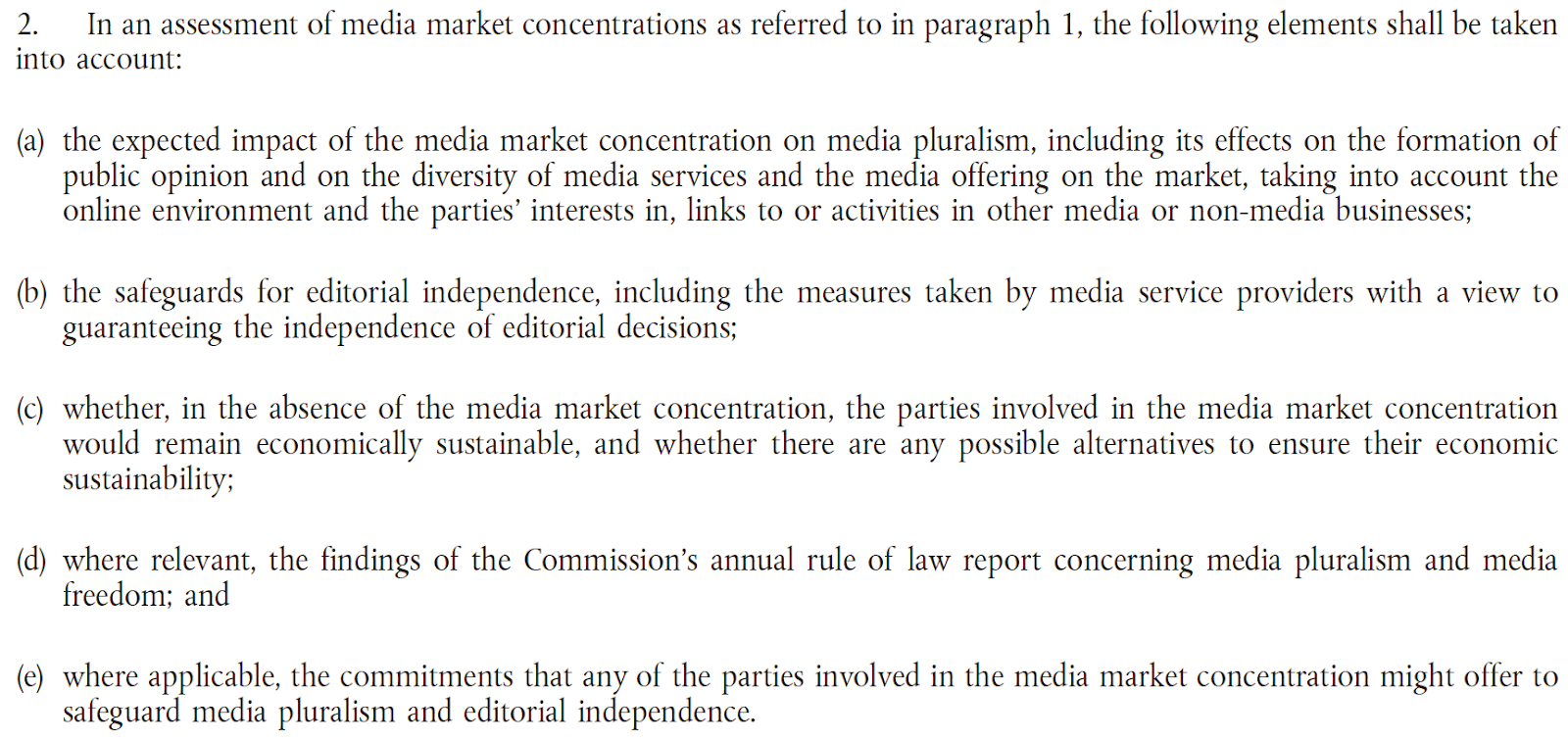

Art. 22 of EMFA addresses the problem of fragmentation of the national rules, with the goal to “set out a common framework for assessing media market concentrations across the Union” (rec. 63). This is done through a soft harmonisation, setting an obligation on the Member States to introduce in the national legal framework an assessment of media market concentration based on common criteria and procedures (a “media plurality test”).

Before analysing the scope of the provision, it is important to highlight what it does not do. The provision is not a tool for tackling concentration in the media sector as such; it just intervenes when a merger occurs. Existing high levels of concentration that could significantly impact media pluralism and editorial independence, and even new concentrations arising from the market growth of a player, or closures or downsizing of other players, are not caught by the provision. The overall level of concentration in the market gets into the game only within the monitoring exercise envisaged in the final provisions of the EMFA (art. 26). Moreover, the article is not self-applying, but its implementation depends upon the Member States’ compliance.

Nonetheless, the provision is very important and its scope is not limited to the media service providers, as the definition of “media market concentration” includes other actors whose role is relevant for the media market, even if they do not offer nor have editorial responsibility for media services1. With ‘media market concentration’ is indeed meant “a concentration (…) involving at least one media service provider or one provider of an online platform providing access to media content” Art. 2(15).

Considering the role of the online platforms as social media and search engines in offering side-door access to media content, this definition opens the path to a significant application of the “media pluralism test” to mergers involving the digital intermediaries.

The criteria of the media plurality test

As shown in the excerpt below, the elements based on which the impact of media mergers on media pluralism shall be evaluated are multifaceted and go beyond the economic sphere.

These criteria shape the media pluralism test with some key characteristics: first, a holistic view of the media market plurality, taking into consideration not only the shares of the revenues in the market but the broader concept of opinion power (defined in the article as “effects on the formation of public opinion”). In order to take into account those effects, information on the media consumption habits should be collected and considered (an example is the model of the “public interest test” in the UK system, see Ofcom 2024). Second, the assessment must be framed in the online environment of the media. Third, the presence of both media and non-media business interests within the parties’ undertakings is considered a significant and negative factor in the media pluralism test. This provision reflects growing concerns about a new wave of media acquisitions driven by the potential to leverage opinion-shaping power for the benefit of owners’ non-media business interests, which are often closely tied to political influence. According to MPM 2024 findings, owners of major media outlets have significant links, activities, or interests in non-media sectors in ‘many cases’ across 18 countries, in ‘some cases’ in 10 countries, and only in 4 countries is there no risk of such mixed interests. Fourth, media pluralism and editorial independence are strictly intertwined in the provision of art. 22: the special assessment is triggered by any mergers that may impact media pluralism and editorial independence. Fifth, the need to preserve and guarantee economic sustainability of the media is strongly affirmed as a key criterion to be considered in the assessment, but it must be proved that there are no better alternatives to the proposed merger to maintain the merged media alive.

Finally, even in the dire circumstance of an unsustainable economic situation for the merging media, the commitment of the merged entity to safeguard media pluralism and editorial independence can be demmed a decisive condition for the approval of the merger. This is an interesting novelty, transforming what might otherwise be viewed as a behavioral commitment into a structural one. In other words, the safeguard of media pluralism and editorial independence should be assured post-mergers insofar as it constitutes an essential permanent condition for the approval of the merger. Even though the order in which the criteria of art. 22(2) shall be interpreted is not specified, it seems clear that in case of mergers which are necessary for the survival of the media outlet, the media authority (or other National Regulatory Authority designated by the national law) can submit the approval to the introduction of permanent ex-post remedies to guarantee internal pluralism and editorial independence.

The challenges ahead

The forthcoming guidelines, to be issued by the Commission with assistance from the European Board for Media Services, will likely clarify uncertainties in the broader aspects of the criteria. For instance, it would be important to clarify how the online environment will be considered, to prevent any overly broad interpretation that could undermine the media pluralism test. Specifically, it should be made clear that the mere existence of vague alternative sources of content on the internet should not be seen as a guarantee of pluralism.

When it comes to the crucial dilemma plurality versus sustainability, the double role of editorial independence as a value to be preserved and, at the same time, an effective “structural” remedy, is an interesting innovation, enabling the media authorities (or NRAs) to allow mergers when there are credible permanent commitments of the merged entity to guarantee ex-post internal pluralism and editorial independence.

Article 22 of the EMFA leaves many open issues. It does not explicitly face the possible contrast between its new test and the probably looser competition evaluation of a media merger. What if there is a conflict? Will the interest of preserving pluralism always prevail, as it seems implicit in the spirit of the law?2 Perhaps the most significant and pressing issue is what can be done when control over opinion formation is already established before any merger takes place.

Nevertheless, Article 22 of the EMFA represents a positive development. It urges Member States to reduce fragmentation in the single market and places media pluralism and editorial independence at the forefront of the analysis. While further interventions will be necessary to achieve broader progress in media sustainability and pluralism, this marks an important first step.

References

Baker, C. E. (2007). Media concentration and democracy : why ownership matters. Cambridge University Press.

Brogi, E., Borges, D., Carlini, R., Nenadić, I., Bleyer-Simon, K., Kermer, J. E., Reviglio della Venaria, U., Trevisan, M., & Verza, S. (2023). The European Media Freedom Act : media freedom, freedom of expression and pluralism. European Parliament.

Carlini, R., Cádima, F. R., Flynn, R., & Kalbnenn, J. C. (2024). Media viability vs market plurality : a comparative perspective : the growing tendency towards media ownership concentration in the digital ecosystem. In Media viability vs market plurality : a comparative perspective : the growing tendency towards media ownership concentration in the digital ecosystem. Routledge.

Doyle, G. (2016). Why ownership pluralism still matters in a multi-platform world, in Valcke, P., Sükösd, M., & Picard, R. G. (Eds.). Media pluralism and diversity : concepts, risks and global trends. Palgrave Macmillan.

Habermas, J., Bürger, T., & Kert, L. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere : an inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Polity Press.

Ofcom (2024). Online news. Research update (published 25 March 2024). https://www.ofcom.org.uk/media-use-and-attitudes/media-plurality/social-media-online-news/

Schlosberg, J. (2017). Media ownership and agenda control: the hidden limits of the information age. Routledge.

Seipp, T. J. & Helberger, N. & de Vreese, C. & Ausloos, J. (2024). Between the cracks: Blind spots in regulating media concentration and platform dependence in the EU. Internet Policy Review, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2024.4.1813

Footnotes

- In the EC proposal for the EMFA, online platforms were not included in the definition of media market concentrations. The limits of the scope for the assessment of media market concentrations were highlighted by Brogi et al. (2023), and are mentioned among the “blind spots” of EMFA in Seipp et al. (2024); in this blogpost, we argue that with the final text of the EMFA those limits have been at least partially overcome. ↩︎

- In this article, Marta Sznajder highlights the risk of a fragmented interpretation, arguing that “the doors remain open for countries to decide which should be given priority in case of a conflicting result.”

↩︎