By Alina Ostling

The number of internet users is growing and digitisation is increasingly shaping all aspects of our life. Also the media is increasingly going digital, providing citizens with opportunities to access a variety of sources, to express themselves and to share information. At the same time, people often lack the necessary skills to critically examine information and to use the vast variety of digital tools available to them. Improved media literacy among the population could help to address some, albeit not all, of the arising challenges. People that become more literate are also more able to widen their range of media alternatives and strengthen their agency to participate in the public sphere.

Definitions and frameworks

There are various definitions of media literacy. The European Commission Expert Group on Media Literacy (2016) defines media literacy as a set of “technical, cognitive, social, civic and creative capacities that allow a citizen to access, have a critical understanding of the media and interact with it.” Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator, puts it more simply as “the ability to use, understand and create media and communications in a variety of contexts.”

With the growing importance of digital media the terms used to define “media literacy” – such as ICT and digital literacy, information literacy, and UNESCO’s Media and Information Literacy (MIL), – have become more intertwined and overlapping. For example, the term ‘digital literacy’ is often used in a similar way to ‘information literacy’ “in the sense of an ability to effectively and critically access and evaluate information in multiple formats, particularly digital, and from a range of sources, in order to create new knowledge, using a range of tools and resources, in particular digital technologies” (UNESCO 2013, p. 29).

Also frameworks for categorising and assessing media literacy abound. One of the prominent ones is the pyramid of the European Association for Viewers Interests (EAVI), clusters media literacy according to two dimensions: Environmental factors and Individual competencies (EAVI 2009). At the very basis of the pyramid, the Environmental factors cover pre-conditions that facilitate or hinder the development of media literacy, such as informational availability, media policy, education and the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the media community. Going higher up on the pyramid, the Individual competences include cognitive processing, analysis, and communication skills (EAVI 2009, p 8).

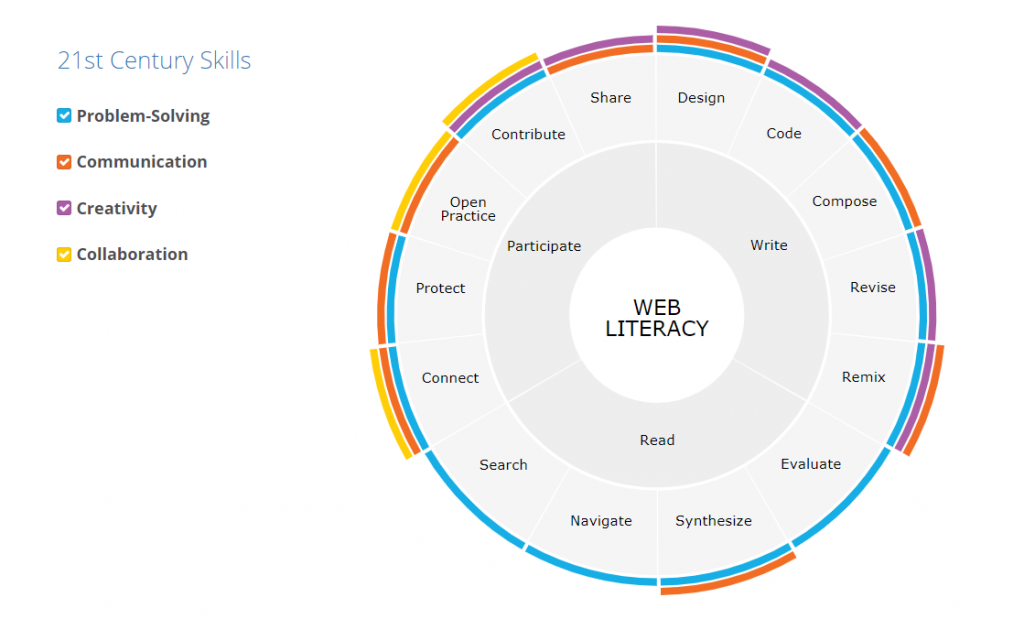

More recently, Mozilla has developed the very comprehensive Web Literacy framework aiming to capture so called “21st Century Skills”: Problem-Solving, Communication, Creativity and Collaboration. The framework relies on three pillars: read, write and participate on the web; and covers 14 sub-categories, such as ‘evaluate’, i.e. comparing and evaluating information from a number of sources online to test credibility and relevance. With the help of this framework, Mozilla aims to help people to develop their literacy in a proactive way; not only as consumer but as active participants e.g. in trainings or in the writing of software code.

Figure 1. Web Literacy framework by Mozilla

The European Commission has attempted to measure the digital skills of the population with its Digital Scoreboard Agenda. The Agenda includes a composite indicator covering four types of skills: information, communication, problem solving, and software skills for content manipulation. However, this indicator has a substantial gap: it adopts a narrow definition of digital literacy and falls short of measuring the ability to interpret and to critically assess online content. In general, despite the variety of media literacy definitions and frameworks, the majority of research at the European level has focused on what is easier to measure, such as technical skills, online access skills, and media consumption (Celot 2015). The question about how to measure the more complex and critical issues, such as the capacity of people to evaluate and produce media messages, remains open and is subject to controversy among Member States.

Media literacy policies

Not only are media literacy definitions different, so are media literacy policies across Europe. This has implications for media literacy levels. Existing research clearly shows that there is correlation between the existence of government policies on media literacy and the individual levels of media literacy (Livingstone 2011). This implies that media literacy policies are important also for defining the type of media literacy skills developed by the population.

At the European level, the key policy document, the European Audiovisual Media Services Directive (2010) has taken a loose stance on media literacy. The Directive does not put any specific obligation on the Member States; it only requires them to promote and monitor the progress on media literacy. The loose framing at the European level has lead to an array of different policy approaches at the national level. Some of these policies assign a passive role to citizens by trying to protect them from harmful content or practices, while some recognise that citizens ought to be empowered to become active and critical individuals who are able to engage in democratic practices (Frau-Meigs et al. 2017). At the same time, our first screening of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2017-data, shows that policies in several European countries tend to be geared towards supporting technical skills and the usage of digital media, at times this comes at the expense of promoting citizen participation and agency.

Conclusion

This brief took stock of the framings of media literacy, both in terms of definitions and public policies, and reflected on how these are changing in the increasingly digital public sphere. The evidence suggests that both media literacy measurements and policies might be over-emphasising the user or consumer citizen instead of focusing on people’s agency and capabilities. This poses a risk to the pluralism of media systems, both on- and offline.

References

Audiovisual Media Services Directive (2010). Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 March 2010 on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32010L0013

Celot, Paolo (2015). Assessing Media Literacy Levels in Europe and the EC Pilot Initiative (2015).

UNESCO (2013). Global Media and Information Literacy Assessment Framework: Country Readiness and Competencies. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002246/224655e.pdf

EAVI (European Association for Viewers Interests) (2009). Study on the Assessment Criteria of Media Literacy Levels in Europe for the European Commission, DG Information Society. Final report

https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/library/studies/literacy-criteria-report_en.pdf

Expert Group on Media Literacy (2016). Mandate of the Expert Group on Media Literacy. European Commission. Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. Brussels, 06.07.2016. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/meetings-media-literacy-expert-group

Frau-Meigs D., Velez I. and Flores Michel J. (2017). Public Policies in Media and Information Literacy in Europe: Cross-Country Comparison. London, Routledge.

Livingstone S. (2011). Media literacy: ambitions, policies and measures. Livingstone, Sonia (ed.) COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology), Brussels, Belgium.