Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Sweden

Report authored by Elisabeth Stur – Mid Sweden University and Asta Cepaite Nilsson – Lund University. This country chapter has been edited by the CMPF team.

Context

The debate on news deserts and local media deserts in Sweden can be traced back to 2002, with a study on the impact of local media in Stockholm and its suburbs.[1] The study found that local news coverage was insufficient and even absent in the suburbs, and named this phenomena “medieskugga”, which translates to media shadow in English. Today, this phenomenon has spread all over the country in different forms. The most affected areas are smaller cities and communities in the countryside where the traditional established regional press has reduced its presence, reducing the number of local newsrooms and reporters.

Lately, the problem of local news deserts has come up on the agenda. And yet, there is still no sufficient public debate concerning news deserts and local media in Sweden. There are, however, debates on two issues connected with the future of local media. One concerns press support, which will be modified in 2024.[2] Another is the inadequate funding in 2023, marked by reduced advertising, readers and media users, which has resulted in serious cuts to both content and reporters[3]. One example is public television where some TV programmes have been withdrawn and numbers of journalists given notice.

In Sweden, the representation of community media can be found in established local media and what can be referred to as hyperlocals. Hyperlocal media outlets have developed in the last ten years and are often partially replacing mainstream local media in news desert areas.[4],[5] Such media stems from the strong community engagement of local media entrepreneurs. In their role as journalists, many of them see themselves as traditional news reporters, focused on the fundamental aspects that journalism is expected to encompass such as performing qualitative journalism, and addressing current issues that affect the local population in the area they cover. [6]

[1] Lars Nord, Mid Sweden University and Gunnar Nygren Södertörn University in 2002: Medieskugga, Atlas, ISBN: 978-91-7389-108-0 www.bokforlagetatlas.se.

[2] Statliga Mediestödsutredningen, ‘Kulturdepartementet, regeringskansliet, 2023, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/departementsserien/mediestodsutredningen-redovisar-i-denna_HAB414/.

[3] MedieSverige 2023, Nordicom Gothenburg University, 2023. https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/publikationer/mediesverige-2023.

[4] L. Jangdal, A. Cepaite Nilsson and E. Stúr,’Hyperlocal Journalism and PR: Diversity in Roles and Interactions,’ Observatorio, 13 (1), 2019, pp. 1646-5954.

[5] G. Nygren, ‘Journalistiken i det lokala samhället’,Handbok i journalistikforskning, ed. M. Karlsson and J. Strömbäck, Lund: Studentlitteratur AB, 2019. pp.283-295.

[6] L. Jangdal, A. Cepaite Nilsson and E. Stúr, E., 2019.

Main findings

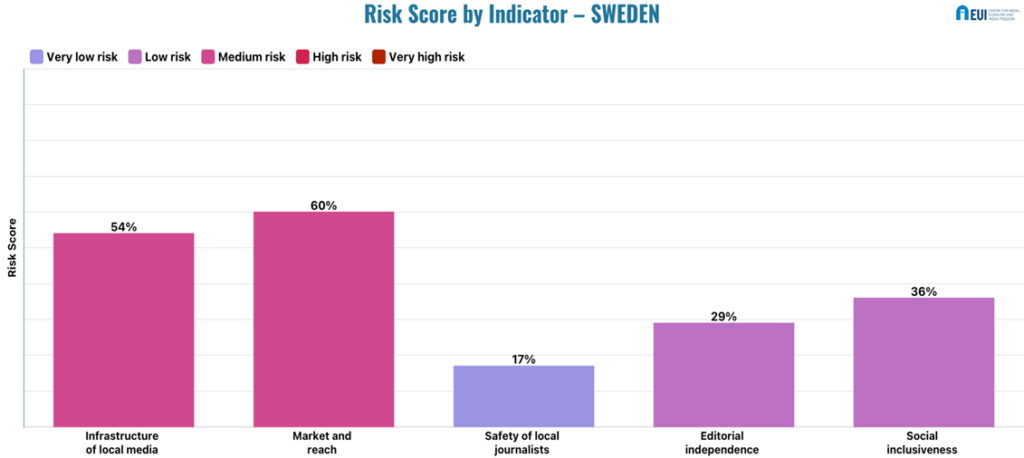

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (54%)

Local media services are present in rural, suburban and urban areas. However, a decline can be identified in the last ten years regarding rural areas and smaller cities, resulting in medium risk for the granularity of the local media infrastructure. Traditional local newspapers have been re-organised and are nowadays doing most of their news work at central newsrooms in the capital cities of the regions: while most local newspapers have survived, their content has become less locally focussed and is often reused within the conglomerates, and, thus, newspapers become less local as a result. The centralisation continues in order to save money, while at the same time, there is an awareness that readers expect local content. It is a difficult balancing act[1].

Between 2017 and 2023, news desert areas, also called “blank spots”, have become more frequent but have somewhat ceased to expand over the last few years. Examining the country as a whole, it is evident that in the north of Sweden, there are more blank spots than in the South.[2] There is mapping in the Mediestudier database,[3] showing the development of blank spots in Sweden where municipalities lack local newsrooms.

In Sweden, the number of local reporters situated in rural areas and in small cities has decreased, along with local newsrooms. More than half of all local newsrooms have closed down, circa 35-40 % of local reporters have disappeared from the local media market, and most local reporters are nowadays based in centralised newsrooms in the capital or larger regional cities. Only occasionally do they leave the newsroom to report on bigger events in rural areas,[4] which is why high risk was assigned for the presence of local reporters on the ground.

With regard to the presence of local branches and correspondents of PSM (Swedish Television (SVT) and Swedish Radio (SR)), a low-risk evaluation was assigned for the granularity of their infrastructure because newsrooms with local journalists are predominantly based in the main regional cities. Collectively, they cover every region and province in Sweden, and broadcast local news regularly, on a daily basis.[5] Concerning public service radio, there are 24 + 1 local radio stations, each of them covering one province/region in Sweden plus one covering Stockholm and its suburbs. However, the main Swedish news agency, Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå, (TT) – which mainly conducts desk journalism – does not keep correspondents in smaller cities and no longer has locally based newsrooms: their only venues are in Stockholm and in bigger cities such as Gothenburg and Malmö.[6]

The map you can find at the following link refers to the number of local newsrooms in Sweden in 2023. The original data source for this visualisation is Institutet för Mediestudier and you can access it here.

[1] G. Nygren and C. Tenor, Lokaljournalistik – nära nyheter I en global värld, Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2020, p. 49.

[2] “Mediestudier.” Mediestudier, 2021. https://mediestudier.se/publikationer/mediestudiers-arsbok-2021.

[3] J. “Kommundatabasen,” n.d. https://kommundatabas.mediestudier.se/.

[4] G. Nygren and C. Tenor, “Svenska trender 1986 – 2022”, SOM institutet Gothenburg University, https://www.gu.se/som-institutet/resultat-och-publikationer.

[5] Mediemyndigheten, “Regler för radio- och TV-sändningar”, n.d. https://mediemyndigheten.se/ansokan-och-registrering/regelverk/regler-for-radio–och-tv-sandningar/

[6] Mediesverige 2023; Nordicum, “Svensk medieutveckling | Nordicom,” n.d. https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/fakta-analys/svensk-medieutveckling.

Market and reach – Medium risk (60%)

There are signs of declining local and community media revenues, largely attributable to changing media consumption habits, among other things.[1] In fact, according to “Svenska trender 1986-2022”, the consumption of local news in local papers and local broadcasting has declined from 78% to 61% between 1986 and 2022. By contrast, the consumption of news using social media has slightly increased in the last five years.[2]

Broadly speaking, the number of local outlets has declined in recent years, with larger media companies acquiring smaller ones, contributing to a less diverse media landscape.[3] In this Report in 2022, 90 out of a total of 96 daily newspapers, consumed at a mid- to high-frequency level, were owned by one of the five largest news groups.

Swedes have a long tradition of subscribing to quality newspapers in print, both local and national.[4] However, the decline of the market is also visible in a continuing decrease in the proportion of households subscribing to a daily newspaper. In recent years, the decline levelled off and a small increase was noticed in 2020.

The turnaround is also explained by a growing interest in digital newspaper subscriptions. For both the metropolitan and rural press, the digital reach and thus digital readership continues to become increasingly important. However, hyperlocal media outlets are financially vulnerable and usually not long-lived.[5] The data on total weekly audience reach for daily newspapers (i.e. those who read a local newspaper once a week) in recent years (2015, 2020-22) show a slight increase from 83% in 2020 to 85% in 2022.[6] The local media market in Sweden is, at the moment, rather stable. But reflecting on the past decade, there have been some significant changes. One of these is how the larger media houses have acquired and incorporated smaller local media companies. This has changed the Swedish media market from being diverse and pluralistic to a few major media owners dominating the market.[7]

The Swedish local media market is very concentrated (very high risk). In recent years, there has been consolidation in the local media market, resulting in a decrease in the number of local media companies, with large media companies such as Bonniers, Norrköpings Tidningar, Gota Media, and Stampen acquiring smaller, local media outlets. For example, Bonniers now owns Mittmedia and Hall Media, gathered under the company Bonniers News Local. The latter also cooperate with Gota Media, thus contributing to a further consolidation of the local media market.[8] [9]

The distribution of both national and local press has decreased over the past five years, especially in the countryside where people depend most on the national postal delivery. In recent years, the delivery procedures have changed from five days a week to sometimes once a week. This development has affected the whole distribution chain, resulting in fewer people being involved in distributing and selling papers; at the same time, the number of points of sales has declined.[10]

National public service radio and TV are financed by taxes. The economy of public service has undergone some reductions which has affected the organisation of SR and SVT and also the support/financing of local media within the organisation – both concerning content production – leading to a decreasing number of employees. [11]

While local media outlets have access to state support in the form of subsidies handed out by “Mediestödsnämnden” (Media Support Board), they have been decreasing in recent years, particularly for the TV, press and radio sectors. However, action was taken in November 2023, when the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, authorised a new package of media subsidies designed to target media outlets in underserved areas (commonly referred to as “white spots” or “Vita fläckar-stödet” in Swedish) (Sverige Riksdag, 2022). This law went into effect on 1 January 2024. The new press subsidy is supposed to support local media, but several media owners, as well as journalists, have expressed their concerns that it will be counterproductive, forecasting that there will be fewer print media in the future.[12]

There has been a sharp decrease in commercial advertising revenue for local media in recent years (high risk). This is a critical development, states Professor Ingela Wadbring, who was interviewed for this research.[13] According to Mediesverige 2023, the biggest loss of investment concerns the daily print press. Between 2005 and 2021, the investment in commercial advertising declined from 8.3 to 1.7 billion Swedish krona (SEK). This affects the economy of the local press, which is heavily dependent on income from advertising.[14]

The willingness to pay for local news has been assessed as medium risk. Despite evidence of declining subscriptions for print media (5% decline in 2021), this has been partially compensated by evidence of increasing subscriptions to online news. Subscriptions for print media were reported to be declining in 2021[15], however, based on the latest Reuters Digital News Report[16], 33% of people in Sweden are willing to pay for online news, which represents one of the highest results in this research. Payment is required to access PSM news, which being public TV and radio, is financed mainly through taxes.

[1] Mediesverige 2023; Nordicum, “Svensk medieutveckling | Nordicom,” n.d. https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/fakta-analys/svensk-medieutveckling.

[2] “Svenska trender 1986-2022” SOM institutet Gothenburg University https://www.gu.se/som-institutet/resultat-och-publikationer.

[3] Mediesverige 2023; Nordicum, “Svensk medieutveckling | Nordicom,” n.d. https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/fakta-analys/svensk-medieutveckling.

[4] O. Westlund, Digital News Report 2022, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/sweden.

[5] G. Nygren, ‘Medieekologi – ett helhetsperspektiv på medieutveckling’, In: ‘Människorna, medierna och marknaden: Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om en demokrati i förändring’, Stockholm: Wolters Kluwer. Statens offentliga utredningar, 2016, pp. 85-108, 2016.

[6] Mediebarometern 2022. GU: Nordicom https://www.mprt.se/globalassets/dokument/publikationer/medieutveckling/medieekonomi/medieekonomi-2022.pdf.

[7]Mediesverige 2023 Nordicom Gothenburg University https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/fakta-analys/svensk-medieutveckling, 2023: Mediesverige 2023; https://ju.se/portal/vertikals/blogs/jonkoping-international-business-school/bloggposter/2022-09-09-agarskap-och-politisk-vinkling-av-nyhetsmedia-den-svenska-tidningsmarknaden.html#:~:text=Men%20efter%20de%20senaste%20sammanslagningarna,där%20Bonnier%20är%20överlägset%20störst.

[8] Mediekartan över den Svenska mediemarknaden 2022, https://www.mprt.se/medieutveckling/.

[9] Mediesverige, 2023, https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/publikationer/mediesverige-2023.

[10] Mediesverige 2023 Nordicom Gothenburg University https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/fakta-analys/svensk-medieutveckling.

[11] Årsredovisning Sveriges Radio Förvaltnings AB, 2022, https://www.srf.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Arsredovisning-SRF-210101-211231-slutversion.pdf; https://www.mprt.se/medieutveckling/.

[12] Dagens Nyheter, Kulturnyheter: Journalistik, 2023-12-24

[13] Professor Ingela Wadbring, interview conducted on 21.06.2023.

[14] Interview with professor Ingela Wadbring on 21.06.2023; Nordicom Gothenburg University https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/publikationer/mediesverige-2023.

[15] Reuters Institute Digital News Report: Sweden. 2022. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/sweden

[16] Reuters Institute Digital News Report: Sweden. 2023. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023/sweden

Safety of local journalists – Very low risk (17%)

The working conditions of employed local journalists are regulated by agreements made between the journalists’ trade union (Svenska Journalistförbundet – SJF)[1] and media outlets. Therefore, employed members of the union have acceptable working conditions in terms of labour rights, including minimum rates of pay and access to social security benefits. In the last few years, there has been a drop in the number of permanent employment contracts among local news reporters, with a decrease in the regular staff reports, as local media outlets have opted for temporary contracts, which usually offer lower salaries. Working conditions of freelancers vary and depend on what kind of agreement they have with the agency/media outlet they are working for. Those who have a particular agreement/assignment may have the same conditions as employed journalists. There are general agreements concerning freelancers, which comprise issues such as average salary, social security protection and working hours, but this depends on the agreement with local media outlets. SJF negotiated a new agreement on working conditions in 2015, which has strengthened the working situation of freelancers in the country.[2]

Attacks and threats to the physical safety of journalists, including those online, have increased in the last 5 years. These attacks and threats often target designated journalists and can sometimes be politically initiated. The frequency of these attacks differs between national and local media journalists, where the latter are not as much affected as those working for national media. [3]

The problem of threats and intimidation against journalists has been addressed in an investigation by the SJF, launched in 2014 and completed in 2018. In the study, nearly 30% of all journalists in Sweden had been threatened over a period of 12 months in 2019, and 70% had received disrespectful comments.[4] The SJF, which is a professional organisation as well as a trade union with approximately 13,700 members, is usually present at the local level when it comes to the organisation of professionally active journalists. Individuals applying for membership of the Union of Journalists enter into a contract with the union. This contract confers both rights and obligations – the members promise to comply with the union’s statutes and code of professional ethics and not to damage the reputation of journalists as a professional body. Furthermore, the SJF negotiates locally on behalf of its members. “At the local level, it is the branches that negotiate on behalf of the members’ rights and promote them.”[5]

The SFJ has guidelines on ethics and professional integrity, which are also part of the education curricula of journalists in Sweden at universities and other training programs.[6] Therefore there is awareness about these subjects among journalists and local media owners.

There have been SLAPP cases against local journalists, however they are rare: one example was the lawsuit against the on-line magazine Realtid.se, filed in London in 2020.[7]

[1] Journalist Kongressen Otryggheten i mediebranschen. Rapport 1-6 av Kent Werne. 2018. https://www.sjf.se/system/files/2018-08/otryggheten_i_mediebranschen_-_rapport_1-6_av_kent_werne.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See Svenska Journalistförbundet, “About the Swedish Union of Journalists”, 2023. https://www.sjf.se/about-us.

[6] See “Rules of Professional Conduct.” Svenska Journalistförbundet, 2020. https://www.sjf.se/yrkesfragor/yrkesetik/yrkesetiska-regler/rules-professional-conduct.

[7] “SLAPP Lawsuit Suing Swedish Online Magazine Realtid Filed in London – ARTICLE 19.” ARTICLE 19, December 2020. https://www.article19.org/resources/slapp-realtid-in-london/.

Editorial independence – Low risk (29%)

In Sweden, no law prevents political control which might be exerted through ownership. While this lack of regulatory safeguards might pose some concern, there is no evidence that parties or individual politicians, directly or through intermediaries, have any control over local media.

In terms of state subsidies, the Press support scheme was replaced in 2019 by the so-called Media support scheme. At the end of 2023, a new legislation replaced the old system where two different subsidies (“press” and “media”) were provided.[1] The new legislation, in effect since January 2024, provides only one form of direct state subsidisation, which is technology and format neutral.[2] The new legislation has faced some criticism, specifically relating to the fact that it does not separate between national and local media, and thus pits them against each other, which critics fear will lead to a less diverse media landscape.[3]

With regard to state advertising, authorities appear to be among the largest buyers of services from advertising agencies and communication consultants. However, no data is found when it comes to the fairness and transparency of the distribution of state advertising in the local media sphere.

Upon analysing the degree of commercial influence over editorial content, it appears that safeguards are in place. For example, the Swedish Association of Journalists has developed guidelines for journalists and editorial boards to follow, in order to maintain their credibility[4]. Moreover, there is no evidence that would prove the attempts of commercial actors to influence editorial content of the local media.

In terms of editorial content and its independence from political influence, organisations such as Sveriges Radio AB (SR), Swedish Journalistförbundet (SJF) and Tidningsutgivarna (TU) as well as Sveriges Tidskrifter, have developed a number of self-regulatory codes of conduct to establish editorial independence. Freedom of the press (SFS, 1949:105) and expression is guaranteed in the constitution, in the freedom of the press ordinance, and in the freedom of expression fundamental law. The Swedish Freedom of the Press Act specifically regulates independence when it comes to the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief[5]. Regulation and self-regulation appear to be effective.

The authority for press, radio and television (MPRT) has approximately 40 employees divided into four units: Application, Supervision, Administration and Communication, and Environment. In addition, there are two boards, the Review Board (GRN) and the Media Support Board (MSN), as well as a Transparency Council. The two committees are independent decision-making bodies within the authority. While it does not have local branches, the authority has a remit over local media.

In Sweden, there are three public service companies: SVT (television), SR (radio) and UR (Education radio). In SVT, there is a part representing local TV and the same in SR, for local radio. No concern has been detected in this research when it comes to local branches. Regulatory safeguards exist[6] and they are generally considered effective in preventing governmental or other forms of political influence. Following a recent change to the articles of association of SR, SVT and UR, members of their boards may not hold a party-political assignment, a practice that has already been established in the past. [7]

Finally, there is the risk of reduced supply and reduced media diversity within the segment of Swedish news and local journalism (medium risk). There are fewer unique local news reports and more are produced using ready-made information from other actors, i.e., identical news published by several different publishers.[8]

[1] Nordicom, Direkt mediestöd till nyhetsmedier – en nordisk översikt, 2022

[2] Law 2023:664 on media support: “Lag (2023:664) om mediestöd.” Sveriges Riksdag, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2023664-om-mediestod_sfs-2023-664/. Ordinance 2023:740: “Förordning (2023:740) om mediestöd.” Sveriges Riksdag, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordning-2023740-om-mediestod_sfs-2023-740/.

[3] Svt, Trots massiv kritik – nytt mediestöd på gång, 2023,

https://www.svt.se/kultur/trots-massiv-kritik-nytt-mediestod-pa-gang–joq13w.

[4] Svenska Journalistförbundet, 2023, https://www.sjf.se/yrkesfragor/yrkesetik/spelregler-press-radio-och-tv/riktlinjer-mot-textreklam.

[5] Freedom of the press law (2018:1801) “Tryckfrihetsförordning (1949:105) (TF) | Lagen.Nu,” https://lagen.nu/1949:105 ; Freedom of expression fundamental law (1991:1469)“Yttrandefrihetsgrundlag (1991:1469).” Sveriges Riksdag, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/yttrandefrihetsgrundlag-19911469_sfs-1991-1469/. ; Sveriges Riksdag:“Fria och oberoende medier (Motion 2004/05:K227 av Göran Lennmarker m.fl. (m)).” Sveriges Riksdag, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/motion/fria-och-oberoende-media_GS02K227/.

[6] Public service is protected, like all media, from state influence at the editorial level through, among other things, the Freedom of Expression Act (chap. 3 § 6), which prevents the state from interfering in individual programmes. “Sök mediestöd 2024.” Mediemyndigheten.se, https://www.mprt.se/stod-till-medier/allmant-om-stod-till-nyhetsmedier/.

[7] Regeringen och Regeringskansliet. “Regeringen säkerställer public service-företagens oberoende från partipolitik.” Regeringskansliet, 2023. https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2023/10/regeringen-sakerstaller-public-service-foretagens-oberoende-fran-partipolitik/.

[8] G. Nygren and C. Tenor, Lokaljournalistik – nära nyheter I en global värld, Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2020.

Social inclusiveness – Low risk (36%)

The PSM, SVT, has a prominent role in broadcasting in minority languages in Sweden. News programmes in Finnish and Sami have existed for a long time, and efforts have been invested to further strengthen and broaden the news offering.[1] Sweden scores low risk for representation of minorities in the media in the latest Media Pluralism Monitor report.[2] Sveriges Radio‘s mission includes having a range in national minority languages such as Finnish, Sami, Meänkieli, Romani Chib and Yiddish.[3]

When it comes to local media providing sufficient public interest news, the risk has been assessed as medium. Studies conducting news content analysis show that, compared to 2007, news on politics, social issues and also lifestyle has increased, while crime, sports, culture and the environment decreased in 2018.[4] Research on hyperlocal media states that these media in Sweden “offer a diverse range of topics, providing inhabitants with a wide variety of information about what is happening in their communities, and with a clear emphasis on local material as opposed to regional or national material.”[5]

Physical proximity to their readers and local reporters’ visibility and anchoring in local society is a prerequisite for building relationships between a newspaper and its audience. In Sweden, some local media outlets, both mainstream and hyperlocal, engage directly with their audience, by being present in the local community and having contact with local people. Unfortunately, there is also a risk that local media outlets could lose this connection through lack of financial and human resources, moving to centralised content production as well as desk-bound news production.[6]

[1] Regeringen, 2023 https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/50fcc2ac408d46b4a919cdf7e53006cb/sveriges-television-ab.pdf.

[2] M. A. Färdigh, ‘Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Sweden’ ,EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://hdl.handle.net/1814/75740

[3] Utbildningsradion, UR 2023, https://kontakt.ur.se/guide/modersmal-minoritetssprak.

[4] Karlsson and Färm, ‘Från brott till sociala frågor – förändring av nyhetsämnen’, In: Mediestudiers innehållsanalys 2007-2018, Michael Karlsson (red), Lars Truedson (red). Institutet för mediestudier, 2018.

[5] L. Jangdal, ‘Hyperlocals Matter: Prioritising Politics When Others Don’t,’ Journalism Practice, vol. 15, no. 4, 2021, p. 450.

[6] E. Stur, A. Cepaite-Nilsson and L. Jangdal (2018), “Hyperlocal Journalism and PR: Diversity in Roles and Interactions”, Observatorio (Obs*) Journal , Vol 12, number 4, 2018, pp. 087 – 106

Best practices and open public sphere

An example of best practices in community media is the phenomenon of hyperlocals. There are about 75 hyperlocals spread all over the country. [1] Most of them are initiated by former local journalists or people with a journalistic interest in producing local news. They function as local news entrepreneurs whilst setting up news media outlets in places which the ordinary local media has ceased to cover. [2]

In terms of innovation in local news, one successful example is that of Horisont, a news magazine which covers the Island of Gotland. It is produced both on print and online and is mainly financed by subscriptions, advertising and sponsorship. The editor is a former news reporter who worked on one of the island’s local newspapers.[3] Another successful example of hyperlocal news media is MAGAZIN 24, situated in the small Swedish town of Köping: The editors have, in recent years, changed the content and appearance on the local media market by making the print and web edition more local news oriented and thus improving the accessibility for their readers. It has, therefore, become the most important source of local news in the area it covers. To deliver this, they receive financial support from the government and local stakeholders.[4]

[1] Entrepreneurship and hyperlocals in the countryside, series of studies of hyperlocals in Sweden 2016-2020.

[2] L. Jangdaal , 2022, ‘Hype or hope?’ The Democratic Values of Swedish Hyperlocals in the Media Ecology : Mid Sweden University;The Democracies Values in the Media Ecology,’ Mittuniversitetet, 2022.

[3] Interview with Christer Böhle, editor of Horisont, 2022.

[4] Magazin 24, Köping, 2024, https://magazin24.se/koping.

Map of Local Newsrooms in Sweden

This map shows the number of local newsrooms in Sweden in 2023. You have the option to filter by media format, municipality and county. Hover over a municipality to view the number of media outlets, giving a breakdown by format. Clicking on a specific municipality provides a detailed list of media outlets in the table below the map, complete with information on media format. The original data source for this visualization is Institutet för Mediestudier and can be accessed by clicking here.