Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Romania

Raluca Toma and Roxana Bodea, Median Research Centre

Context

Romania stands out among European countries in its relatively low news consumption across the board, contributing to a somewhat small and resource-poor news media market.[1] What is more, local media in Romania were hit particularly hard by the 2008 economic crisis and its aftermath, meaning many local publications never recovered.[2] Local publications were among the first to fold or retreat into online-only editions as a result of the crisis. There are now far fewer local print publications left, and their circulation numbers are low. Discussions on the problems facing news media outlets, both national and local, are mostly limited to small circles of industry and industry-adjacent professionals—in particular journalists, NGO observers, other media professionals—rarely reaching the mainstream public sphere. When they come up, local media markets and outlets tend to be talked about as contexts where the problems observed in the news media industry or market at large are exacerbated. Thus, the crisis of local media receives relatively little mainstream attention, and when it is discussed, possible policy solutions are, at best, an afterthought.

The available data suggest that online local media cannot compensate for the reduction in availability of local print news. According to our estimations, there are up to seven counties without specific online outlets focused on their area.[3] Besides, the internet is not yet the main source of news for most citizens. Only around 20% of Romanians turn to the internet as a main source of news, according to Eurobarometer 92.[4]

Television and radio are still the main ways most Romanians get their news, yet it is unclear how much of the citizens’ need for locally- and regionally-relevant news can be covered by these media. Eight in ten Romanians name TV as their number one or two source of news, and three in ten name radio.[5] In addition to the public regional stations, there are 14 television stations with local reach, based in cities, as well as a number of private regional TV stations,[6] and almost all counties have at least one local radio station.[7] Yet it is not possible to ascertain how much—if any—news content is delivered.

Lack of data is a significant problem for understanding the Romanian local media landscape. In many cases there is no data whatsoever, and in others, data is not aggregated, only available on request, not updated regularly, or posted in formats that are not machine readable.

[1] European Commission, ‘Standard Eurobarometer 94 – Winter 2020-2021 – Media in use in the European Union – Report’, 2022, pp. 16-19, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2355 (accessed 24 May 2022). R.Bodea and M. Popescu, ‘Journalistic and Business Strategies of an Investigative Journalism Media Organization in Romania’, Presentation at the World Media Economics and Management Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 6-9 May 2018. R. Bodea, ‘Turmoil and Transformation. A Comparative Study of Newspaper Market Adjustment (2008-2013)’, M.A. Thesis, Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences & Solvay Business School, Communication Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 2018.

[2] M. Popescu, R. Bodea and R. Toma. ‘Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2020 in the European Union, Albania and Turkey in the years 2018-2019. Country report : Romania’, 2020, https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/67815. M, Popescu, R. Bodea, A. Marincea and R. Toma. ‘The Online News Media Landscape in Romania’, 2019.

[3] Pooling data from multiple sources, a total of 99 regional or local online news outlets were identified, covering 32 counties of the 40 counties of Romania. For 8 counties, no print or online titles were identified, in that particular county (Bistrita Nasaud, Buzau, Caras-Severin, Dambovita, Giurgiu, Gorj, Harghita and Hunedoara). Harghita can be considered to benefit from coverage by a regional online publication in Hungarian focused on Harghita and Covasna County (also dubbed “Szeklerland” sometimes). Sources: The Study of Online Audiences and Traffic (SATI), produced by BRAT, Similarweb and Media Cloud.

[4] European Commission. ‘Standard Eurobarometer 92 – Autumn 2019 – Media use in the European Union’, 2020, : https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2775/80086

[5] European Commission, 2020.

[6] Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului. ‘LICENŢE AUDIOVIZUALE pentru difuzarea serviciilor de programe de televiziune prin rețele de comunicații electronice (inclusiv prin satelit) și în sistem digital terestru [AUDIOVISUAL LICENSES for the broadcasting of television programme services via …]’. 2023, https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/Licente_audiovizuale_pentru_difuzarea_serviciilor_de_programeTV_SITE.pdf . Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului. ‘Situația Numarului De Licente / Societate – Televiziune [Status of License Number / Company – Television]’, 2023, https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/Situatia_numarului_de_licente_TV_SITE-3.pdf.

[7] Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului. ‘LICENȚE AUDIOVIZUALE pentru difuzarea terestră și prin rețele de comunicații electronice a serviciilor de programe de radiodifuziune [AUDIOVISUAL LICENSES for terrestrial and electronic communications network broadcasting of radio programme services]’. 2023. https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/Licente_audiovizuale_pentru_difuzarea_serviciilor_de_programeRadio_SITE pdf (accessed 1 October 2023). Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului. ‘Situatia Numarului De Licente / Societate – Radiodifuziune [Status of the Number of Licenses / Company – Broadcasting]’, 2023, https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/Situatia_numarului_de_licente_Radio_SITE-3.pdf .

Main findings

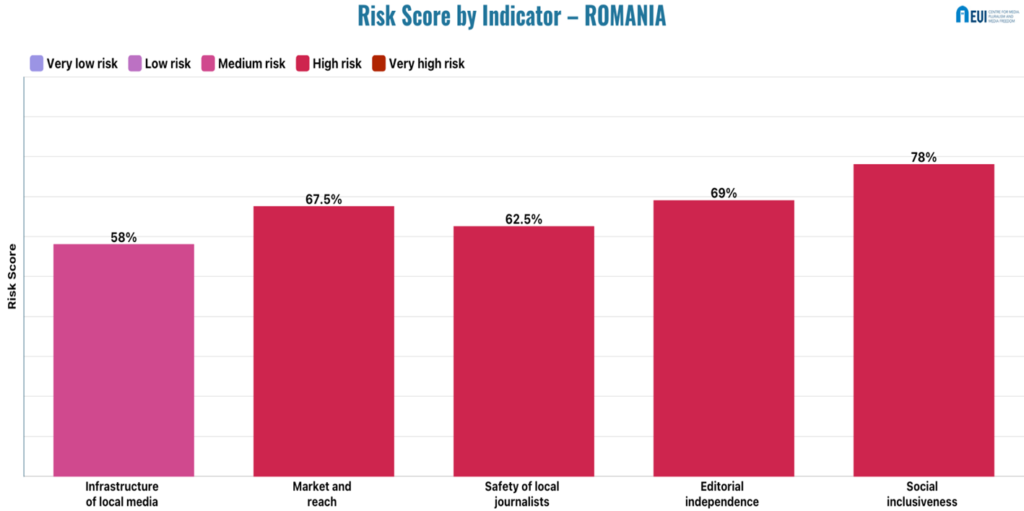

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (58%)

The overall risk score for the indicator on the granularity of infrastructure of local media is 58% (medium risk). All other areas have an even higher risk score, which illustrates the dire state of local media in Romania.

Rural areas are the most news-deprived, due to the limited number of locally—as opposed to regionally—relevant news outlets available, leading to a very high risk rating on this variable. Urban areas are better served, with more TVs and radio stations.

Public service media (PSM) have the most comprehensive reach. As mentioned in the previous section, TV is the number one or two source of news for most Romanians,[1] and there are five regional PSM TV stations, broadcasting some regionally relevant news in 10-30 minute slots: TVR Mures (based in Târgu Mureș, covering the North West); TVR Craiova (based in Craiova, covering the South-West); TVR Iași (based in Iași, covering the North East); TVR Cluj (Cluj-Napoca-based, covering the Central Region); and TVR Timișoara (based in Timișoara, Western Region). Yet public television stations have a small audience: TVR1, the main television station of the public broadcaster, ranked 14 in prime time in 2023, per the latest data.[2] There are also nine regional public radio stations, covering the entire country,[3] and the public news agency had an average of 37 local correspondents in the country, over the past five years.[4]

The number of print publications has declined in the past 15 years. The National Audience Study (Studiul National de Audienta – SNA), ordered by the Romanian Transmedia Audit Bureau (BRAT), an industry group,[5] audited 54 print local and regional publications in 2008. By 2018 that number had gone down to 12, and in 2023, it covered only two local publications (Crisana and Bihoreanul).[6]

There are now only about a dozen daily or weekly local news print publications participating in BRAT’s print audit. Most of these are found in the Central and Western part of the country.[7] They have very small circulation numbers: mean circulation for this group was 2,800 in July-September 2023, per BRAT data.[8]

Internet penetration is not universal yet, and rural areas have a higher share of households without internet and of persons with fewer digital skills. In 2022, 26% of rural households had no internet connection, while only 11% of urban households lacked internet.[9] In urban areas there are more local television and radio stations (although it is unclear how much news content they produce).[10] Additionally, there are few local/regional print titles left, and their circulation is very low, as discussed in the introduction.

One of the major national outlets, Adevărul, has an established section on local news of significant size. Adevarul.ro was sixth among Romanian news websites in December 2023, with 4.7 million unique users, according to SATI. It has a network of local collaborators who publish almost daily, covering 39 counties, including the capital city.

[1] European Commission, 2020.

[2] P. Obae, ‘AUDIENŢE TV 2023 Prime-Time. Câţi români s-au uitat seara la TV? Pro TV rămâne cel mai urmărit şi singurul peste milion. Antena 1, singurul care creşte şi urcă peste Kanal D în ţară. Surprizele FilmCafe şi Cinemaraton’, 2024 https://www.paginademedia.ro/audiente-tv/audiente-anuale/audiente-tv-2023-prime-time-seara-top-televiziuni-21449604.

[3] The national radio (Radio Romania) has nine regional branches. They are based in the following cities: Bucharest, Brasov (Brasov county), Cluj-Napoca, Constanta, Craiova, Iasi, Resita, Targu-Mures and Timișoara. It is however not possible to report on how much news content rather than music and entertainment they produce.

[4] AGERPRES headquarters are based in eight cities: Botoşani, Cluj, Gorj, Harghita, Mureş, Olt, Vaslui and Bistriţa-Năsăud. In the last five years it had 37 local “special” correspondents on average (with a high of 40 in 2019 and a low of 35 in 2020 and 2022), all of whom work full time (all but 4 work exclusively with the agency). All correspondents are based locally (Source: Freedom of Information Act request response).

[5] The Romanian Transmedia Audit Bureau is an industry group of media publishers, advertising companies, advertising clients and other organisations connected to the business.

[6] M, Popescu, R. Bodea, A. Marincea and R. Toma, 2019. Biroul Roman de Audit Transmedia. ‘Rezultate de audienta SNA FOCUS [SNA FOCUS audience results]’, 2023, https://www.brat.ro/sna/livrare/sna-national-iun20-iun23/.

[7] Bihor: Jurnal Bihorean, Bihari Naplo, Bihoreanul, Crisana; Harghita: Hargita Népe; Covasna: Observator de Covasna; Arad: Jurnal Aradean; Mures: Zi de Zi; Satu Mare: Gazeta de Nord Vest.

[8] The highest circulation in July-September 2023 was 8,192 for Harghita Nepe, followed by 6,032 for Jurnal Aradean and the lowest 600 for Gazeta de Nord Vest and (preceded by OBservator de Covasna, with 892). Biroul Român de Audit Transmedia. ‘Cifre de difuzare iulie septembrie 2023 [Circulation numbers July September 2023]’. 2024, https://www.brat.ro/audit-tiraje/cifre-de-difuzare (accessed 9 January 2024).

[9] Institutul Național de Statistică. ‘În anul 2022, ponderea gospodăriilor care au acces la reţeaua de internet de acasă a fost de 82,1%” [In 2022, the share of households with access to Internet at home was 82.1%]’, 2023, https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/com_presa/com_pdf/tic_r2022.pdf (accessed 1 October 2023).

[10] There are in fact 38 counties that have at least one radio company that holds only one licence (i.e. a licence for only one locality). Most of these licences are issued for broadcasting in urban localities, not rural ones.

Market and reach – High risk (67.5%)

Revenue trends are difficult to gauge due to lack of aggregate data. For companies owning the local print press, the trend appears to be downward.[1] Of the online local media, four out of the five top performers are owned by the same companies owning the print publications and the fifth may not be representative at all (but it had an extraordinary rise in revenue in recent years).[2] The revenue evolution of the top radio and TV stations in the past five years involves wild variation, with no clear trend.

There is little information about the willingness of Romanian audiences to pay for news, but the existing information suggests a low willingness to do so. Arguably, both the available statistics and the lack of higher quality data justify the very high risk rating in this area. Survey data on willingness to pay for news in general offers a sense of a general trend that may apply to local news as well. in a 2023 online survey (n=2,017) conducted for the Reuters Digital News Report, 16% of respondents reported a willingness to pay for online news.[3] In a 2022 Flash Eurobarometer survey (n=2,110), of the survey participants who reported having read online news in the past year, only 20% reported having accessed any paid content (20% did not know and 60% said they only accessed free content).[4]

The number of local TV stations may be going down, if the number of local licences issued by the national regulator is a good indicator. It is however also possible that existing outlets narrowed their broadcasting range.[5] The number of local radio licences has registered a very small increase, but it is not clear if the number of outlets increased, or the range of the existing ones did.[6]

The print paper distribution chain has collapsed in the past few decades, especially after the 2008-2009 crisis. Local paper distribution and national publication distribution outside of the capital were particularly affected by the bankruptcy of printers as well as distribution companies, thus this variable was assessed as holding a very high risk score. Print distribution, historically done mainly through newspaper stands and—to a lesser extent—via mail distribution of print subscriptions, is still a challenge[7]. In the years following the economic crisis, both the number of newsstands and of distribution companies halved. While in 2010 there were 6,500 newspaper kiosks in the country, by 2017 that number had gone down to 3,000.[8] Half of the distribution companies had reportedly gone bankrupt, and many others were in dire financial situations.[9] As written in the Media Pluralism Monitor country reports, in Romania there is essentially no support and no serious consideration given to supporting through subsidies the production of high-quality information on public interest affairs.[10] There are no direct subsidies, and the only indirect subsidy is a reduced Value Added Tax (VAT) rate for print, which has almost no impact on the media sector as a whole due to the low number of print outlets remaining in the country. This VAT reduction is automatically applied. As for state advertising, it is worth underlining that the aims and therefore the allocation criteria of state advertising projects differ significantly from state subsidies. Whereas state subsidies aim to support the production of (certain) kinds of media content, state advertising campaigns aim to get a particular message out to the highest share of people possible out of the target audience. Consequently, allocation criteria can and should be different.[11] A few private grant schemes are available, but none destined for local media specifically, so local media competes with national media.[12]

[1] The remaining print outlets are owned by a total of five companies. Inform Media Press SRL owns Jurnal Aradean, Bihari Naplo and Jurnal Bihorean. Szekely Hirmondo is owned by Profiton SRL; Observator de Covasna by Comparty SRL; and Crișana by Anotimp Casa de Presa si Editura SA. Between 2017 and 2022, the total revenue for these five (adjusted for inflation) went down by 90%. Ministerul Finanțelor. ‘Agenţi economici şi instituţii publice – date de identificare, informaţii fiscale, bilanţuri [Economic agents and public institutions – identification data, fiscal information, balance sheets]’, 2023, ://mfinante.gov.ro/domenii/informatii-contribuabili/persoane-juridice/info-pj-selectie-dupa-cui.

[2] Four of the top five online local news websites are owned by companies covered under print, above (overall loss in past few years). The remaining company, Prima Press SRL, registered a 3,000% growth in revenue between 2017 and 2022, but this is probably not representative of the online local news media landscape, considering this is a Hungarian language publication and, according to press reports, most of the funding of Prima Press came through projects they applied for abroad. Biroul Roman de Audit Transmedia. ‘Rezultate trafic proprietati online [Online property traffic results]’, 2023: https://www.brat.ro/sati/rezultate/type/site/page/1/c/all.

[3] N. Newman,R. Fletcher, K. Eddy, C.T. Robertson and R. Kleis Nielsen. ‘Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023’. 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf (accessed 1 October 2023).

[4] European Commission. ‘Media & News Survey 2022’, 2022, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2832.

[5] One has to use this proxy because no aggregate numbers were provided. In 2019, there were 145 active local television licences and 52 regional ones (for private companies). The national TV company (TVR) had 5 regional TV channels. Four years later, in 2022, there were 94 active local TV licences and 56 regional ones (for private companies), and TVR had the same number of TV channels. Thus it appears that the number of outlets decreased, or existing outlets narrowed their broadcasting range. Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului. ‘Raportul de activitate al Consiliului Național al Audiovizualului pe anul 2022 [The activity report of the National Broadcasting Council for 2022]’, 2022, https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/1_CNA_Raport_de_activitate_pe_anul_2022.pdf.

[6] In 2019, there were 562 active local radio licences and 8 regional licences, issued to private companies. There were also 13 regional and one local licences issued for the National Radio Company (SRR). Four years later, in 2022, there were 565 active local licences and 15 regional licences, issued to private companies, and 12 regional and one local licence for SRR. Thus, it is possible that the number of outlets increased but it could also be that existing outlets expanded their range of localities.

[7] Lupu, 2020, pp. 13, 20.

[8] C. Tolontan. ‘Sentinta. Un judecător i-a spus lui Daniel Băluță că ocupația sa ca primar nu e „încărcarea rolului instanţelor de judecată cu cereri lipsite de temei” contra jurnaliștilor” [Sentence. A judge told Daniel Baluta that his occupation as a mayor is not “to fill up the schedule of courts with baseless requests” against journalists]’. Libertatea, 2023, https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/sentinta-judecator-spus-daniel-baluta-ocupatia-sa-ca-primar-nu-e-incarcarea-rolului-instantelor-de-judecata-cu-cereri-lipsite-de-temei-contra-jurnalistilor-4531663.

[9] Obae, 2016.

[10] Toma et al., 2023. Popescu et al., 2021.

[11] For example, it makes sense for a state advertising campaign to fund media that are very popular among the target audience, whereas depending on the aim of a particular subsidy it may not (and probably does not) make sense for it to go to the most popular / lucrative outlets. Funds disbursed by the government in the second half of 2020 as public campaigns in the fight against COVID-19 were clearly advertised and transparently allocated. Some criticised this policy on the grounds that money went to commercial broadcasters, tabloid media, and even media spreading fake news, instead of supporting quality journalism. Although the observations were somewhat accurate, the critique was based on a misunderstanding of the principles of state advertisement and conflated it with state support for public interest news media. Even press reports acknowledge that the size of the audience was the main criterion of allocation. In the months after the ordinance 63/2020 was approved (modified by ordinance 86/2020 and by law 164/2020 which increased the total amount of the advertising budget from 40 million euros to 50 million and expanded the implementation period from end of October to end of December 2020) the biggest TV stations in the country attracted the biggest budgets, as did the biggest radio stations.

[12] The Romania-based Foundation for the Development of Civil Society (FDSC) has some grant programmes (Civic Innovation Fund, e.g.) where media organisations can be eligible for project-based funding. Some smaller non-profit national media have used FDSC funding in the past few years (Recorder, Funky Citizens’ Buletin de Bucuresti project); The Google Digital News Innovation Fund has awarded EUR 1,8 million to 16 entities in Romania, but none of them are local, except for Funky Citizens’ Buletin de Bucuresti (a recent Bucharest-focused online outlet). The Romanian American Foundation awarded the niche narrative journalism (national) print and online magazine Decat o Revista (now defunct) a $86,700 grant for May 2022 – April 2023; $432,417 for 2019-2021.

Safety of local journalists – High risk (62.5%)

The assessment of working conditions is based on the (limited) information it is available about conditions for journalists in Romania in general. Salaries in the media—according to the limited data it was possible to gather—are quite low.[1] Moreover, several media outlets frequently do not pay salaries on time and sometimes for several months in a row. Many people who work in this field also have the kind of short-term, freelance-type contracts that do not come with medical insurance and social security by default and that offer less protection from sudden or arbitrary dismissal. Some of the journalists who do have classic labour contracts report that they are expected to work longer than the hours written into their contracts. For example they may have a half-time contract but be expected to work more than double than that. According to some research, long unpaid internships are common, and some young journalists see accepting precarious (or unpaid) labour as necessary to get one’s foot in the door and earn experience.[2]

There are occasional attacks or threats against journalists, but there is no evidence of an increase in the number of cases. In 2022, a public radio journalist was the target of a public threat by a Hungarian far-right politician, a statement condemned by multiple political figures, including the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR). The same year, the Directorate for Investigating Organised Crime and Terrorism raided the house of a local journalist who had been critical of the Braila police commissioner, in a raid that was ruled unjustified by a local court. In 2023, this research so far identified no attacks and one threat against local journalists.[3]

Another very high risk factor refers to journalists’ organisations, or rather, the lack thereof. There are no journalists’ organisations of a significant size to speak of in Romania at the moment, despite some (relatively feeble) attempts in the past.[4]

The Association of Media Professionals (APCC) is the only active and local membership-based organisation for journalists. It currently has 52 voting members according to its website (apcc.ro).

The information indicates that SLAPP cases occur occasionally, but it is worth stressing the lack of systematically collected and comprehensive data on this. There is no anti-SLAPP legislation at the moment. There are some cases where it is relatively plain to see that a high-profile figure is attempting to use the avenues provided by the courts and other Romanian institutions to inconvenience or intimidate journalists. For example, Daniel Băluță, the mayor of Bucharest’s Sector 4, has filed more than 20 court cases against journalists (mainly from Libertatea) and was critiqued for baseless litigiousness by a local judge in 2023.[5] Finally, the public likely hears about only a minority of the cases of lawsuits against journalistic outlets.

[1] According to data from Paylab.ro, a website comparing salaries from different branches, the range is between the equivalent of 525 EUR and 1,130 EUR (estimate based on June 2023 exchange rate). Cristian Lupsa, the editor of niche magazine and website Decat o Revista, reported in early 2019 that most of the people on his 30-some writing staff make between 410 EUR and 820 EUR, and that giving them all labour contracts (as opposed to collaborator contracts) was a significant financial effort for the organisation (EUR figures based on 30 April 2019 exchange rate). In early 2020, he was reporting that he had managed to raise salaries somewhat, such that the lowest salary band (juniors) in the organisation began at 512 EUR (at the time, he also reported that his most junior person was making 615 EUR) (EUR estimations based on 27 January 2020 exchange rate). Lupsa’s publication closed in 2022 citing insufficient revenue to maintain operations.

[2] R. Surugiu, ‘Labor Conditions of Young Journalists in Romania: A Qualitative Research’. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 81, pp. 157-161, 2013; P. Bajomi-Lázár, ‘A country report for the ERC-funded project on Media and Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe’, 2011; H. Örnebring, ‘Anything you can do, I can do better? Professional journalists on citizen journalism in six European countries’. International Communication Gazette, vol. 75, no. 1, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048512461761.

[3] Journalists from local outlet Incomod allegedly received online threats that are being investigated by local authorities: Incomod. ‘Un fost polițist a amenințat jurnaliștii ziarului Incomod care au scris despre mafia gunoaielor din Prahova: ”Vezi că te arzi”’ [A former policeman threatened journalists from Incomod newspaper that wrote about the trash mafia in Prahova: “Be careful or you’ll get burned”], 2023, https://www.ziarulincomod.ro/un-fost-politist-a-amenintat-jurnalistii-ziarului-incomod-care-au-scris-despre-mafia-gunoaielor-din-prahova-vezi-ca-te-arzi/.

[4] There is an organisation that mainly seeks to defend the interests of journalists working for public radio and public television (MediaSind). R. Toma, M. Popescu and R. Bodea. ‘Monitoring Media Pluralism In The Digital Era. Application Of The Media Pluralism Monitor In The European Union, Albania, Montenegro, Republic Of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey In The Year 2022’. 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75735/romania_results_mpm_2023_cmpf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. M. Popescu, R. Toma and R. Bodea. ‘Monitoring Media Pluralism In The Digital Era. Application Of The Media Pluralism Monitor In The European Union, Albania, Montenegro, Republic Of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey In The Year 2021. Country Report Romania’. 2022, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/74702/MPM2022-Romania-EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[5] Tolontan, 2023; C. Radu, R. Luțac and C. Tolontan. ‘Anul 2021, încheiat cu trei procese pierdute de primarul PSD Daniel Băluță, pe 17, 20 și 22 decembrie, în fața jurnaliștilor de investigație [The year 2021 ended with three trials lost by PSD Mayor Daniel Băluță, on December 17, 20 and 22, in front of investigative journalists]’, Libertatea, 2021, https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/anul-se-incheie-cu-trei-proc ese-pierdute-de-primarul-psd-daniel-baluta-pe-20-21-si-23-decembrie-in-fata-jurnalistilor-deinvestigatie-3907434 (accessed 1 October 2023):

Editorial independence – High risk (69%)

There are, arguably, significant shortcomings in the regulation. The Audiovisual Law regulating the ownership regime for radio and television media does not contain any reference to conflict of interests between media owners and political parties or partisan groups. There is no specific legislation conceived for the written press or digital media ownership, these being regulated only by the general law on commercial enterprises, which does not include such stipulations.

Previous research by civil society organisations has found complex “entanglements in the management and ownership of local television stations”, contributing to a high risk assessment in this variable.[1]

Other organisations, journalists and media observers have reported that local media are very vulnerable to political pressure that is exerted through means other than ownership, and some have characterised some local media as outright politically controlled.[2] For instance, journalists and former journalists interviewed by other organisations in the past and some experts have characterised local outlets as particularly vulnerable to political pressure because much of their advertising money comes from local authorities that are willing to disburse or withhold money on political grounds.[3] Additionally, the line between advertising and editorial content is often blurred, as contracts between local institutions and outlets appear to include not just the purchase of advertising space but also of featured interviews, appearances etc.[4]

There are neither legal nor self-regulatory mechanisms in place to protect journalists and journalistic outlets from commercial pressures, in the form of arbitrary appointments or dismissals or threats thereof[5] or undue pressures to alter content / editorial policy.[6] Very few outlets have even adopted an ethical code, and some cases of abuse have been documented even in such places.[7] Journalists and media observers also report that local media are under particularly high pressure due to the scarcity of funds, including the scarcity of advertisers.[8]

In recent years, leaked documents and numerous anonymous sources have also revealed that many national news media have published political advertising content without signalling it as such, likely leaving their readers with the impression that they are looking at journalistic content.[9] Although there is no specific information about this occurring at the local level, the phenomenon speaks to the weakness of journalistic norms as well as to the impact of funding scarcity that local media experience just as much—if not more—than national media.

The media authority CNA (Consiliul National Audiovizual – National Audiovisual Council) has remit only over audio-visual media. As such, its remit does include local/regional televisions and radio. Decisions to issue penalties are based on the analysis of the staff controllers/inspectors but made by the same members of the Council that decide on penalties related to national broadcasters. Until evidence to the contrary is available one can therefore extrapolate from assessments of the overall decisional practice of the CNA: there is no evidence of systematic bias but in the past there were some cases where occasional partisan bias may have been at play on the part of some members.[10]

As discussed in the section dedicated to the granularity of local media’s infrastructure, public service television and radio have local branches, and the national press agency has local correspondents. No data is found on the degree of political independence displayed by the local coverage of public media. Moreover, there is a lack of systematic and professional analysis of the content diversityof local media, although given the limited options in terms of the number of outlets producing locally-relevant news content in many counties, content diversity itself is likely to be low. The lack of data on these aspects in itself constitutes a high risk.

[1] A 2014 Active Watch report on the state of local televisions concluded that “[p]olitical or economic entanglements in the management and ownership of local television stations are often so complex that you cannot always clearly define the political colour of a television station. In addition, in many cases the data is missing. But according to the data we were able to collect, there are worryingly many cases where local television is a weapon of political and economic warfare sponsored by public money, directly or indirectly. Thus, almost half of the 56 televisions included in the research are directly or indirectly influenced by politicians”. M. Popa, A. Mogoș, M. Pavelescu and Ș. Cândea. ‘Harta politică a televiziunilor locale [The political map of local televisions]’, Active Watch, 2014, https://activewatch.ro/documents/119/Harta_politica_a_televiziunilor_localeFINE.pdf . C. Lupu. ‘Starea mass-media în România. 2020 [State of the Mass Media in Romania. 2020]’.

[2] A 2020 report by the Centre for Independent Journalism, for example, based on interviews with dozens of journalists from the national and local level, asserted that “[t]he lack of money from the public makes the press remain captive to local interests, which arbitrarily finance media products, and the citizen’s interest remains, most of the time, unrepresented” (Lupu, 2020, p. 19). Multiple journalists interviewed talked about political pressures, including at the local level, sometimes exerted via financial support through advertising money (Lupu, 2020, p. 27, 43, 51). Popa et al., 2014. C. Lupu. ‘Starea mass-media în România. 2020 [State of the Mass Media in Romania. 2020]’. 2020 and 2021, https://cji.ro/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/STUDIU-PRESA-2020_roBT-rev-01.pdf and https://cji.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Jurnalismul-in-2021.-O-cursa-cu-obstacole-si-cu-tot-mai-putini-castigatori-raport.pdf.

[3] Lupu, 2020, p. 51; Avădani and Lupu, 2015, p.7, 12, 15; Popa et al., 2014, p. 15. I. Marin. ‘Presa locală, cumpărată cu bani publici: milioane de euro pe ode, emisiuni aranjate și felicitări [The local press, bought with public money: millions of euros for odes, arranged broadcasts and congratulations]’. Recorder. 2018, https://recorder.ro/presa-locala-cumparata-cu-bani-publici-milioane-de-euro-pe-ode-emisiuni-aranjate-si-felicitari/.

[4] Lupu, 2021, pp. 23-24.

[5] Toma et al., 2023, p. 9.

[6] Toma et al., 2023, p. 18-19.

[7] Popescu et al., 2022, p. 15-16, 22.

[8] Lupu, 2020, pp. 7-11.

[9] V. Ilie, M. Voinea and C. Delcea. ‘Prețul tăcerii. O investigație în contabilitatea presei de partid [The price of silence. An investigation into the accounting of party media]’. Recorder. 2022, https://recorder.ro/pretul-tacerii-o-investigatie-in-contabilitatea-presei-de-partid. C. Andrei. ‘Agenția confidențială. Fost lider PNL: „Am plătit promovarea pe site-urile Antenelor, Digi24, Realitatea, B1, RTV, Hotnews” [The confidential agency. Former PNL leader: “We paid for promotion on the Antena, Digi24, Realitatea, RTV, Hotnews websites”]’, Europa Liberă România, 2022, https://romania.europalibera.org/a/lider-pnl-am-platit-site-urile-antene-digi24-realitatea-b1-rtvhotnews-/32031503.html. A. Crăițoiu. ‘Recorder a publicat banii dați de PSD și PNL către unele televiziuni și site-uri, provenind dintr-o scurgere de documente [Recorder has published the money that PSD and PNL gave to certain TV channels and websites, coming from a leak]’. Libertatea, 2022, https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/recorder-a-publicat-banii-dati-de-psd-si-pnl-catre-unele-televiziuni-si-siteuriprovenind-dintr-o-scurgere-de-documente-4277301 .

[10] Toma et al., 2023.

Social inclusiveness – High risk (78%)

Lack of data posed many obstacles to the assessment of social inclusiveness in local and community media. Still, the conclusion is that this indicator has the highest risk score.

The available information suggests that the needs of many groups may be insufficiently met. For instance, public media broadcast very little news content in minority languages: the national television channel (TVR1) broadcasts its television news programme only in Romanian, and only one of its regional branches provides some (shorter) news shows in Hungarian.[1] Radio România Actualități, the national radio news channel, only broadcasts the news in Romanian over the airwaves, and the regional national radio stations also have little to no news in minority languages.[2] Looking at broadcasting licences awarded by the media regulator CNA, only a few private channels offer news content in minority languages.[3]

There is little to no data on the coverage of minorities, especially outside of the Roma community.[4] A 2003 analysis of coverage of the Roma in the news media concluded that the media covered Roma mainly with a focus on conflicts—between the Roma and authorities—and with heavy use of negative stereotypes.[5] A 2021 study on coverage of the Roma amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Romania found that conflictual framings (still) abound and that (negative and stereotypical) presentations of the Roma and scapegoating continue to be a problem.[6]

There are no media outlets specifically addressing marginalised groups in the country with news content, leading to a very high risk rating on this variable. Even women are not specifically targeted as an audience group with politics and public affairs-related content by any media of significant reach.

With regard to initiatives by local media to build audience trust, engage with the audience and the local community, this research did not identify any analyses on such efforts. This lack of data has been assessed to be high risk.

[1] In January 2023, TVR Targu Mures had a Hungarian-language regional news broadcast at 9 am (10m), 4 pm (10m) and 5.30 pm (25m).

[2] According to our research, one of the regional radio channels has some news in minority languages, but they appear to cover only or mainly regional/local news as part of a one-hour slot that also includes music and other content (Radio Timisoara has a German slot from 7pm, a Hungarian slot from 8pm, and Serbian slot from 9pm).

[3] The authors of this chapter identified one (local) news station ERD TV (registered in the county of Covana) that broadcasts news in Hungarian and no television stations broadcasting (Romanian) news in German or other minority languages. We have also identified four radio stations that provide news in Hungarian: Plusz Radio (registered and broadcasting in the county of Bihor), Slager Radio (registered and broadcasting in Sfantu Gheorghe in Covasna County), Erdely FM (registered and broadcasting in Miercurea Ciuc, Harghita County); Szepviz FM (Miercurea Ciuc, Harghita). We found no radio stations broadcasting news in German or other minority languages. Looking at the databases for print publications and online publications signed up for monitoring by the Romanian Transmedia Audit Bureau (BRAT), we found a few news sites and print outlets in Hungarian.

[4] G. Cretu. Roma Minority in Romania and its Media Representation. Sfera Politicii, 2014, https://revistasferapoliticii.ro/sfera/180-181/pdf/180-181.11.Cretu.pdf

[5]Agentia de Monitorizare a Presei. ‘Presa de la “Tigani” la “Romi” [The Press, from “Gypsies” to “Roma”]’, 2003, https://ro.scribd.com/doc/58171848/Imaginea-Romilor-in-TV

[6] I. Chiruta. ‘The Representation of Roma in the Romanian Media During COVID-19: Performing Control Through Discursive-Performative Repertoires’. Frontiers. 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.663874/full

Best practices and open public sphere

Initiatives to experiment with innovative products, distribution models, reporting methods and team organisation modes are limited in number and in scope. One of the more successful examples—with a national scope in terms of subject matter—is Dela0.ro, founded in 2011 and currently employing a team of six, of whom four are reporters and two are editors.[1] The niche narrative journalism magazine Decat O Revista experimented with novel products and revenue streams, such as courses and organising the “Power of Storytelling” conference for several years, but insufficient funding led to a decision to stop publication in 2023.[2] A novel but ultimately unsuccessful example—also with a national scope—is the now-defunct Inclusiv initiative, which launched with a major and successful fundraising effort in 2019 but folded in 2021 without reaching its full journalistic potential.[3] In terms of civil society organisation-backed initiatives, a notable one that has been successful in securing some funding so far is Buletin.de, a project by the Bucharest-based CSO Funky Citizens. For now, Buletin.de/Bucharest covers news from the capital, and it has received EU funds during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as from the Google News Initiative.

[1] Dela0 supplements its written features with multimedia content and a podcast and is funded by donations and grants. It occasionally collaborates/partners with larger publications to pick up its materials.

[2] A. Diură. ‘Punct final. Decât o Revistă se închide după 13 ani. Mesajul fondatorului Cristi Lupşa: “Oricum aş scrie propoziţia asta, tot greu e’. Pagina de media, 2022, https://www.paginademedia.ro/stiri-media/se-inchide-decat-o-revista-dor-20877970

[3] Set up after a large crowdfunding campaign that collected around 100,000 euro, the Inclusiv platform was intended to include subscribers in the process of story selection, as well as tapping into expertise among its base in researching and developing their material, among other planned innovations. Ultimately, however, the project leaders struggled with intra-newsroom disagreements, organisational issues and the project only published around a dozen news stories before closing in 2021. Inclusiv. “Inclusiv se inchide” [Inclusiv is closing], 2021, https://inclusiv.ro/inclusiv-se-inchide/.