Read more

Discussion Series, News

Adapting the Understanding of Media Market Plurality to the New Digital Realities

The conditions and the composition of players in the media markets have seen profound changes over the last decades in ways that potentially affect plurality and diversity. Thus, the understanding of what the media...

By Ľuboš Kukliš

Chair of ERGA and chief executive at the Council for Broadcasting and Retransmission of Slovakia

Twitter: @LubosKuklis

Rules covering news, current affairs programmes and the framework for ensuring citizens are adequately informed during electoral campaigns constitute a significant part of electronic media regulation in many EU countries. So much so that, in some countries, the application of these rules comprises the majority of regulators’ daily workload. Despite this, it may be the most under-explored area of all media regulation, at least from an international comparative perspective.

The main reason for this is likely that these rules are also those least harmonised. While there is some basic background for them in the Council of Europe legislation (European Convention on Transfrontier Television[1]), the EU regulatory framework is not concerned with this type of regulation, and there is generally a considerable variety among national rules. Furthermore, as these rules apply to so-called traditional media (predominately radio and TV), and as their application usually deals with domestic policy priorities in the relevant country, their international impact is fairly limited. It is therefore not surprising that these rules have yet to attract widespread attention (scholarly or otherwise) at the European level.

The current media situation may change this. The ever-increasing number of sources of media content, the degree of their relevance in the eyes of recipients, combined with the subsequent proliferation of dis/misinformation and outright hoaxes, provide a strong impetus for a wide range of players to seek solutions. And if there is a relevant legal framework that connects past and present regulatory experience to the current information crisis, it lies precisely in this area.

This is why the European Regulatory Group for Audiovisual Media Services (ERGA), a group of media regulators from all EU countries that serves i.a., as an advisory body to the European Commission, decided to create a Subgroup that would gather the data on the rules in the EU member states (and other countries participating in ERGA) alongside the practical experiences of national media regulators (NRAs) in this field. And the first report of the ERGA Subgroup on the Media Plurality has been published and is available here.

The ERGA Report

The vibrant patchwork of standards, regulations and legal provisions set out in the Report called ‘Internal Media Plurality in Audiovisual Media Services in the EU: Rules & Practices’ will not fit the new situation seamlessly, but there is much to learn from these frameworks and from the experience of the NRAs in applying them. For that reason, it seems that the time has come to bring national internal plurality frameworks (as they are referred to in the report) to the debate.

The report is divided into four major areas. The first two chapters set the conceptual framework by explaining why it was important to write the report in the first place and is also establishing its scope and basic working definitions.

The second part considers the current state of regulation of internal media plurality in general and then, separately, in connection to elections in all countries participating in ERGA (EU members plus FYROM, Norway and Serbia). In addition to providing a detailed catalogue of available measures, this also grants a unique picture of their application from the perspective of regulators.

To cover all areas, the third section considers changes in the media landscape and their impact on the existing rules. This includes not only the general challenges created and encountered by the evolving media landscape from the perspective of regulators, but also the specific issue of disinformation, where it provides a preliminary snapshot of the existing and planned initiatives.

In its final part, the report offers a look at media plurality from a cross-border perspective.

What is and is not covered

As the outcome of the first part of ERGA’s work on media plurality, this report focuses on the theme of internal plurality with an emphasis on information flow in the media environment.External plurality measures such as transparency of media ownership, rules on media concentration, must carry and must offer are not covered, as these will be the focus of the Subgroup in 2019. The main emphasis in this report therefore is on:

- regulation of and ethical standards applying to media content such as news or current affairs programming (editorial independence, objectivity, impartiality, accuracy, veracity, transparency); “general rules”,

- and regulation of and ethical standards applying to media coverage of elections (the extent, scheduling and the balance of the programmes, moratorium, opinion polls, political advertising,); “election period rules”.

The report gathers input on all the measures (available or planned) in this area, comparing the practice on internal pluralism in the respective countries, including frameworks and standards that extend beyond those within the purview of the individual NRAs. Thus, the report provides information on non-statutory rules and standards concerning internal media plurality found in a number of EU member states, including in sub-legal frameworks set up by professional organisations, broadcasting and media organisations themselves or, in some cases, with the involvement of national regulators and supervisory bodies.

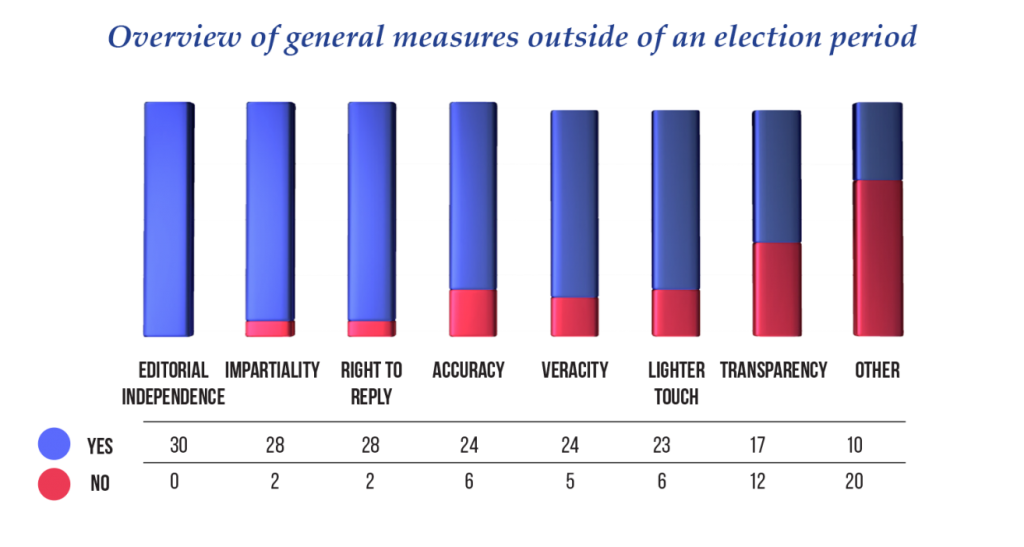

General rules

All NRAs have some measures aimed at protecting these aspects of internal media plurality. Of course, not all categories of measures are available in all countries as can be seen in the table which follows. It does seem, however, that these measures are widespread in every category assessed, ranging from those available to almost all NRAs (editorial independence, impartiality and right to reply), to those available to most NRAs (accuracy, veracity and light-touch approaches) and finally concluding with widespread measures in the area of transparency. Some NRAs pointed out that many of these existing media plurality measures could also indirectly but effectively cover disinformation.

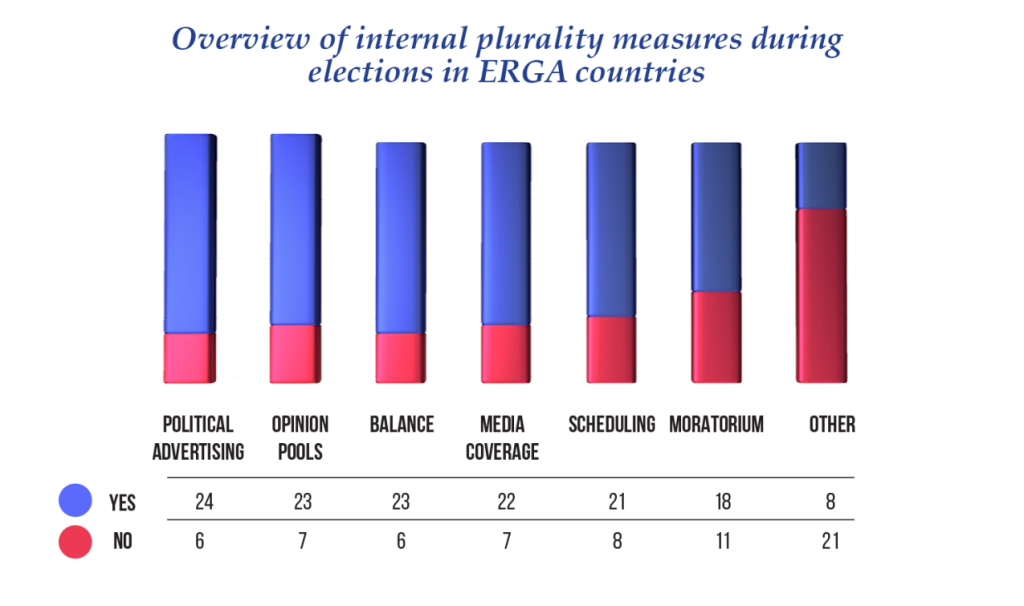

Election period rules

Due to their potential influence, broadcast media have traditionally been subject to detailed and rigorous regulation during election periods. This was to ensure the effectiveness of the protection of the pluralism of all “political representatives” participating in the political-institutional debate and, therefore, requiring access to the media in order to inform the public of their positions. In fact, almost all countries have specific regulations regarding the electoral campaign aimed at traditional broadcasters. At the same time, some NRAs have the role of drafting the rules for the electoral campaigns.

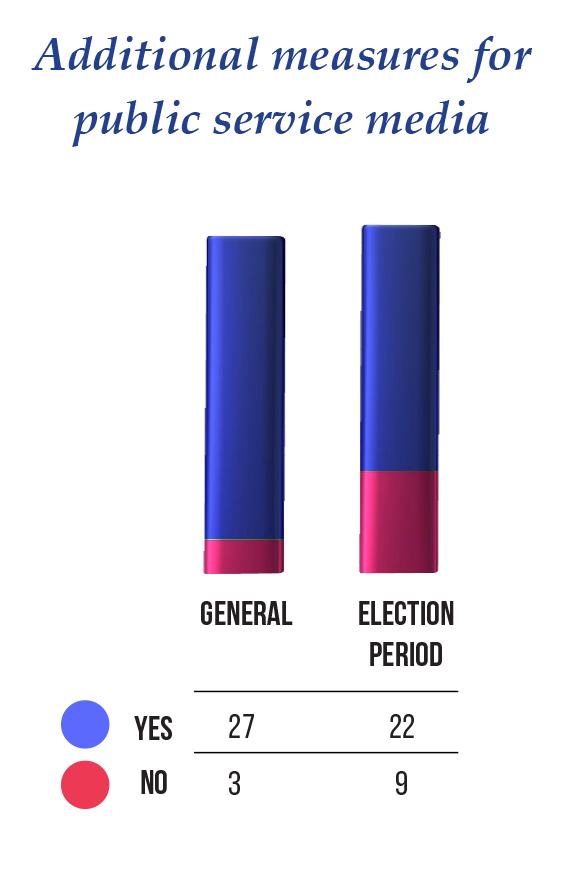

Specific measures for public service media and specific genres

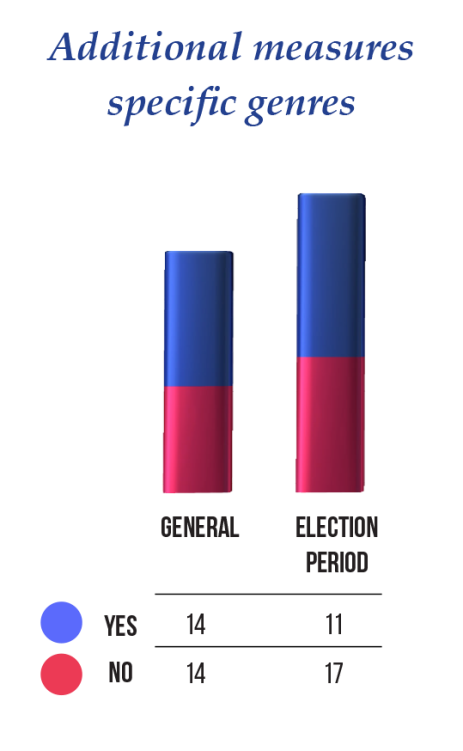

Most countries have additional measures for internal plurality applied to public service broadcasters (both general and election period specific) as can be seen in the graph below. These findings, and additional indicators explored in the report, reveal the importance of the role PSBs play in earning the public’s trust in news and in acting as a common reference for public discourse. In half of the jurisdictions covered by the report, existing measures of media plurality only apply to specific genres of programmes, mainly news, political, and current affairs programmes as specific genres, as well as programmes broadcast by public service media.

Current challenges

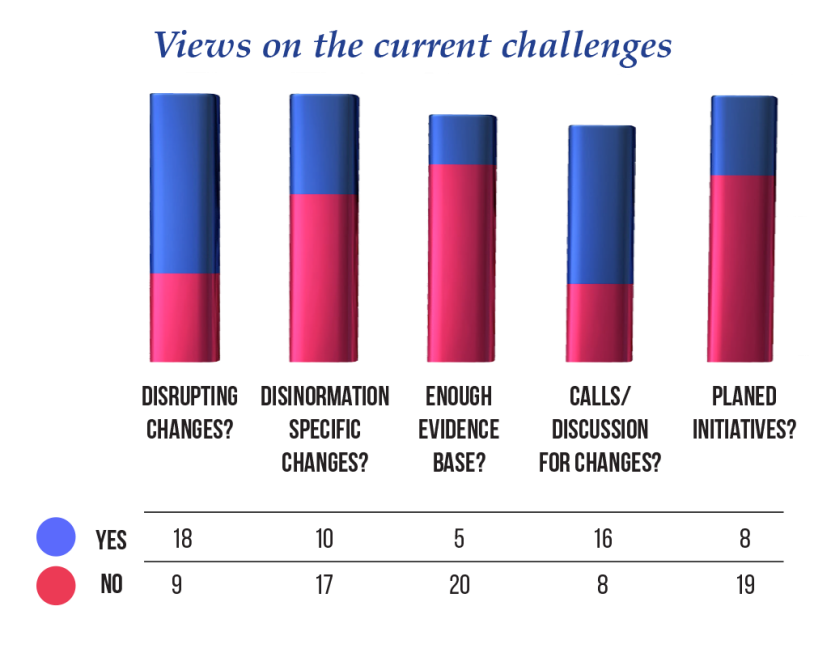

The current challenges faced by the NRAs were also examined closely. It is clear that most NRAs agree on the insufficiency of evidence to properly assess the need for regulatory intervention to secure internal plurality against changes to the media landscape and call for more research on this phenomenon. It also seems that there are discussions and calls for change at the national level and indeed concrete proposals are already being made in this regard in some countries. Insofar as proposed interventions might involve the wider application of the current internal plurality framework analysed in this report, the trends in the media landscape described below could offer some helpful direction.

The following general trends in the changing media landscape have been observed in the report:

- the internet reduces barriers to entry into the market for news, leading to an abundance of news services available to citizens online;

- most people accessing news online do so indirectly instead of going through news websites or applications;

- the news is increasingly viewed on smartphones in the form of ‘news feeds’;

- content discovery online is fragmented;

- in the absence of editorial curation, the news is now sorted into ‘news feeds’ by a combination of algorithms and personalisation by users;

- for most users of social media, the route of content discovery is guided by endorsements and recommendations by friends, with news items discovered in this way less likely to be challenged;

- news content which particularly resonates with members of a social network can go viral, intensifying its effect.

Disinformation

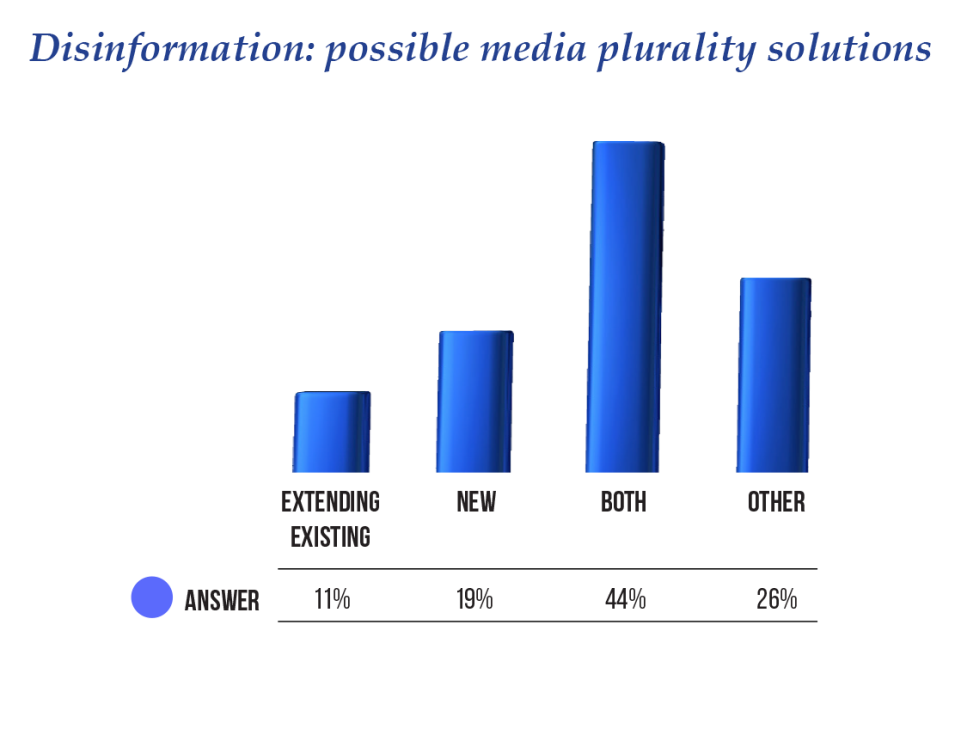

A part of the report also focuses on the phenomenon of disinformation. Where online consumption of news occurs in a largely unregulated space, this could potentially risk undermining the policy objective of internal plurality as an aid to democratic public discourse. It seems that the growing importance of the phenomenon of disinformation is undeniable. Although current concerns stem mostly from the specific ways that the internet and new technologies profoundly affect the dissemination of information, disinformation also exists in the linear and traditional world of media. The approach to intervention in this field is a sensitive topic, especially considering the rights and principles at stake (in particular the freedom of expression and the freedom of information).

In a word, the responses of NRAs on disinformation convey that:

- NRAs have not identified radical changes that relate to disinformation but that the regulators and the public are fully aware of this phenomenon;

- NRAs have recently been expanding research in this field;

- Disinformation can have important consequences on political debate and on decision-making processes;

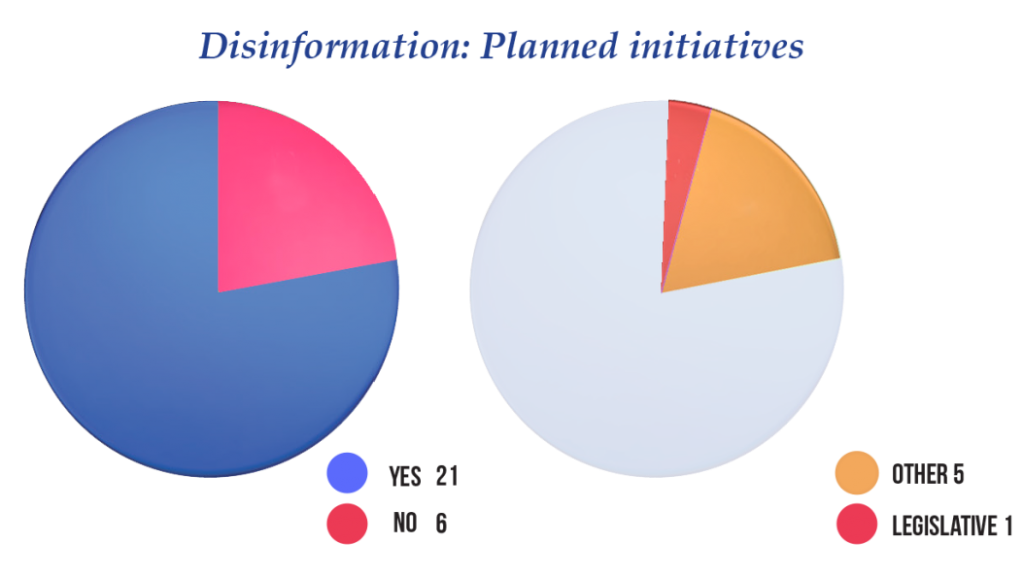

- Most countries have no measures in place tackling the issue of disinformation per se, and those that do almost never employ legislative measures;

- The vast majority of NRAs consider that there is not enough evidence to assess the need for regulatory intervention in this field. However, the number of proposals to tackle the problem of disinformation is growing;

- The vast majority of member states and NRAs favour self-regulation to address this issue; More and more actors (states, NRAs, market players etc.) are working to address this phenomenon. There is recognition that achieving plurality depends on series of measures.

- There are some published and other planned initiatives at the national, European and international level.

Cross-border dimension

The cross-border dimensions of internal plurality were also examined. Cross-border cases involving traditional (audiovisual) media and media plurality are rare and, when they arise, cooperation between NRAs can offer solutions. A question has also been raised regarding the possible challenges posed by new services (Video Sharing Platforms/social media) in the context of internal plurality. Cooperation between NRAs is strong, but most NRAs believe that more would be beneficial and stressed the added value of ERGA. Most see ERGA as a medium for the exchange of information and best practices (also as a discussion forum on the matter). Some regulators believe that ERGA should play a role in cross-border issues, and potentially act as a voice for regulators in discussions with global players over new services.

Next steps

This report should provide a unique NRA perspective on the discussed topics that had previously been missing and will hopefully contribute to debates about the broader question of media plurality in society. True, the internal plurality is just a small part of the whole complex issue. But it is also the one most underexplored so far, and one that deals with topics closest to those the current so-called information crisis is about.

In 2019 ERGA will, therefore, continue

exploring these topics, attempting to answer some of the questions raised in this report – with the

problem of disinformation standing out most prominently, while also focusing on

the regulatory aspects of external media plurality.

[1]Article 7 (3), 10bis, European Convention on Transfrontier Television, ETS No.132, https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/090000168007b0d8