Spain

Download the report in .pdf

English – Spanish

Authors: Pere Masip, Carlos Ruiz, Jaume Suau, Ángel García Castillejo

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Spain, the CMPF partnered with School of Communication and International Relations Blanquerna – University Ramon Llull, who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

The total population of Spain is 46,438,422 people. Native-born Spanish citizens make up 90,5% of the total population and 9,5% are immigrants. Among the immigrants, the main three groups are Romanian (15,8%), Moroccan (15,3%) and nationals from the United Kingdom (6,7%) (INE, 2016a). The most relevant ethnic minority – in terms of population – are the Roma, who represent 1,3% of the population. Roma generally hold Spanish nationality and they are not officially recognised as being a specific minority.

The country is administratively divided in 17 autonomous communities and two cities with statutes of autonomy (Ceuta and Melilla). Spain has only one nationwide official language, which is Spanish (or Castilian). Besides there are six autonomous regions with their own co-official languages: Catalan in Catalonia, Balearic Islands and Valencian Community (also called Valencian), Basque in Basque Country and Navarra; and Galician in Galicia.

The Spanish economy is the fifth-largest in the European Union based on nominal GDP statistics (Eurostat, 2016). Since the financial crisis of 2008, Spain has been plunged into an important recession which has had a significant social impact. The unemployment rate reached an unprecedented record at about 27% in 2013, and dropped to 21,1% in 2015. Unemployment for those under 25 has been reported to be 50% (INE, 2016b).

Since the restoration of democracy after Franco’s dictatorship, the political system in Spain is a multi-party system. However, just two parties have been predominant: Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the People’s Party (PP). Nationalists parties, mainly Convergence and Union (CiU) in Catalonia and Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV) in the Basque Country, have played a relevant role both at regional level and in national politics. In the last few years, new parties have emerged, benefiting from the lack of trust in both hegemonic parties. The most relevant ones are Podemos, which carries the spirit of the Indignados Movement, and Ciudadanos a centre-liberal party. In the last general election of 26 June 2016, Unidos-Podemos and Ciudadanos were the third and fourth parties with 71 and 32 seats respectively (of the total 350 seats).

The political situation in Spain is nowadays highly unstable. The fragmentation of the parties in Parliament, and the inability to establish agreements among them to form Government, implied that the country has been without a new executive for more than one year and two general elections. Moreover, one of the most populated and rich regions, in terms of GDP, Catalonia, has a regional Government and majority in its regional Parliament that have as a short-term political objective to declare independence from Spain. Hence, Spanish political system is facing several challenges that are threatening the system born in 1980s after the reestablishment of democracy.

The media system in Spain follows the Polarized Pluralist or Mediterranean model, as described by Hallin and Mancini (2004). Although having a high number of news media these are normally easy to identify with political positions or political parties. The number of TV channels has been growing since the adoption of Terrestrial Digital Television (TDT). This, together with the widespread adoption of Internet content platforms such as Netflix, has implied a drop in audiences for TV channels. Spain has a dual media system dominated by public broadcasters, both at national and regional levels, and by two main private television groups (Atresmedia and Mediaset).The level of press circulation has fallen during the last 15 years from 4.2 million to 2.3 million copies per day. The average daily newspaper circulation in Spain is 22,170 copies, one of the lowest figures in the EU (AEDE, 2016).

The media market is characterized by an overall dominance of television, attracting about 40% of the total advertising expenditure in the country. Television also remains the dominant source of information (88%), followed by the Internet (68%), radio (60 %), and newspapers (28%) (AIMC, 2016).

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

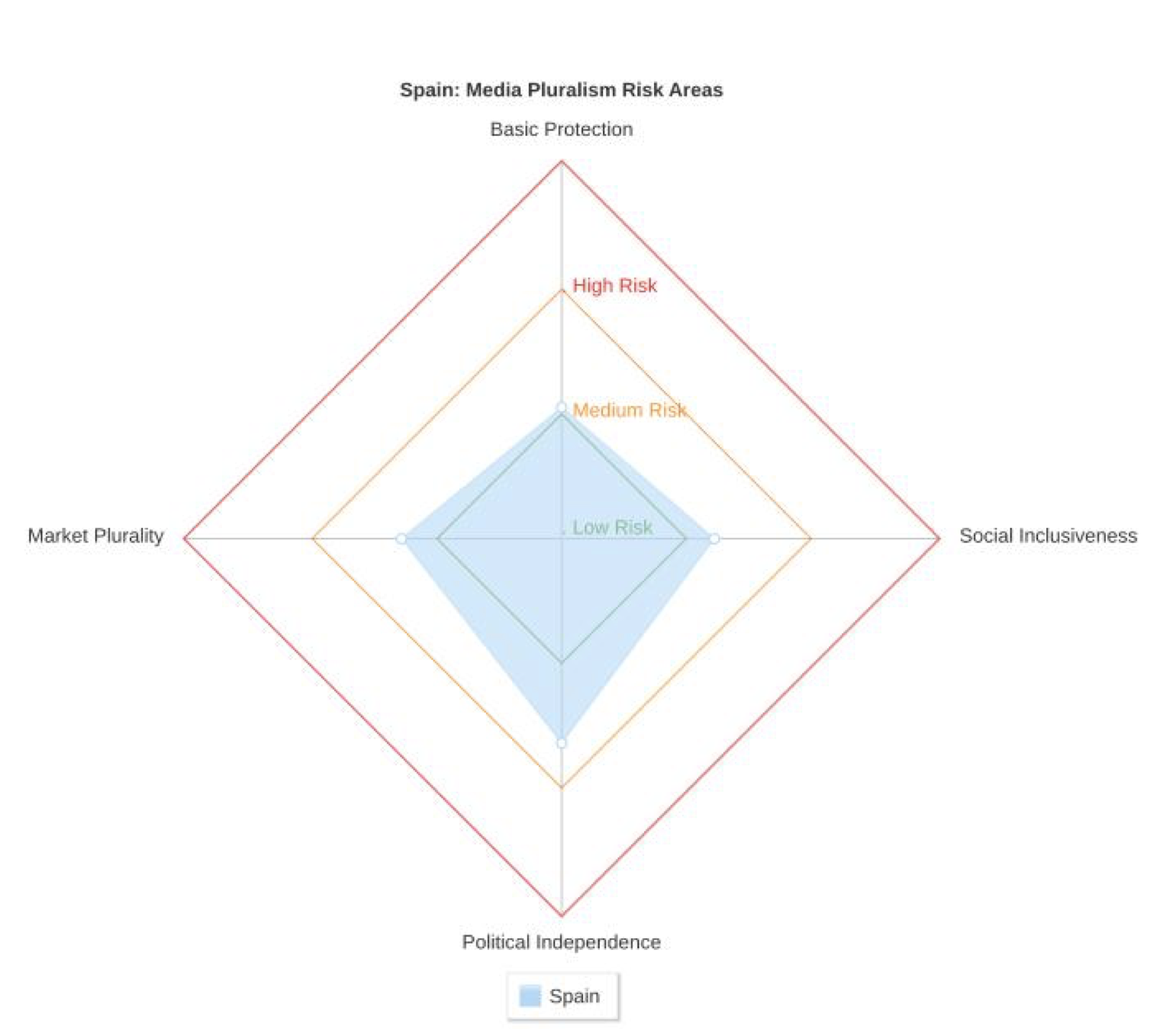

Implementation of the MPM2016 in Spain indicates an overall medium risk to media pluralism. Since the restoration of democracy in 1978, Spain has adopted progressive legislation and developed a comprehensive legal framework for ensuring media pluralism. However, implementation is often weak and ineffective.

All of the four areas: Political Independence, Market Plurality, Social Inclusiveness and Basis Protection, are in the medium risk band, with Political Independence being the most at risk (54%).

In Political Independence area, the indicator Independence of PSM governance and funding scores high risk (83%). Although political influence on the public broadcasting system has been habitual in Spain, reports about pro-governmental manipulation and influences on PSM governing bodies have multiplied in the latest years (IPI, 2015). The rest of the indicators scores medium risk, but Editorial autonomy and Political control over media outlets show significant warning signs and the Indicator Media and democratic electoral process, scores low risk (25%). However, some critical voices, especially from journalists associations consider that the electoral law supposes a political meddling in the editorial process. The law states that during elections, time spent on political news coverage must be distributed in function of results obtained by political parties in previous elections, instead of applying professional criteria, what might damage pluralism and free reporting, according to journalists’ associations.

Regarding to Market Plurality area, it scores medium risk, but one indicator of this area is at high risk (71%): Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement. Although media law provides ownership restrictions in the media sector, specific cross-media concentration limits are not established.

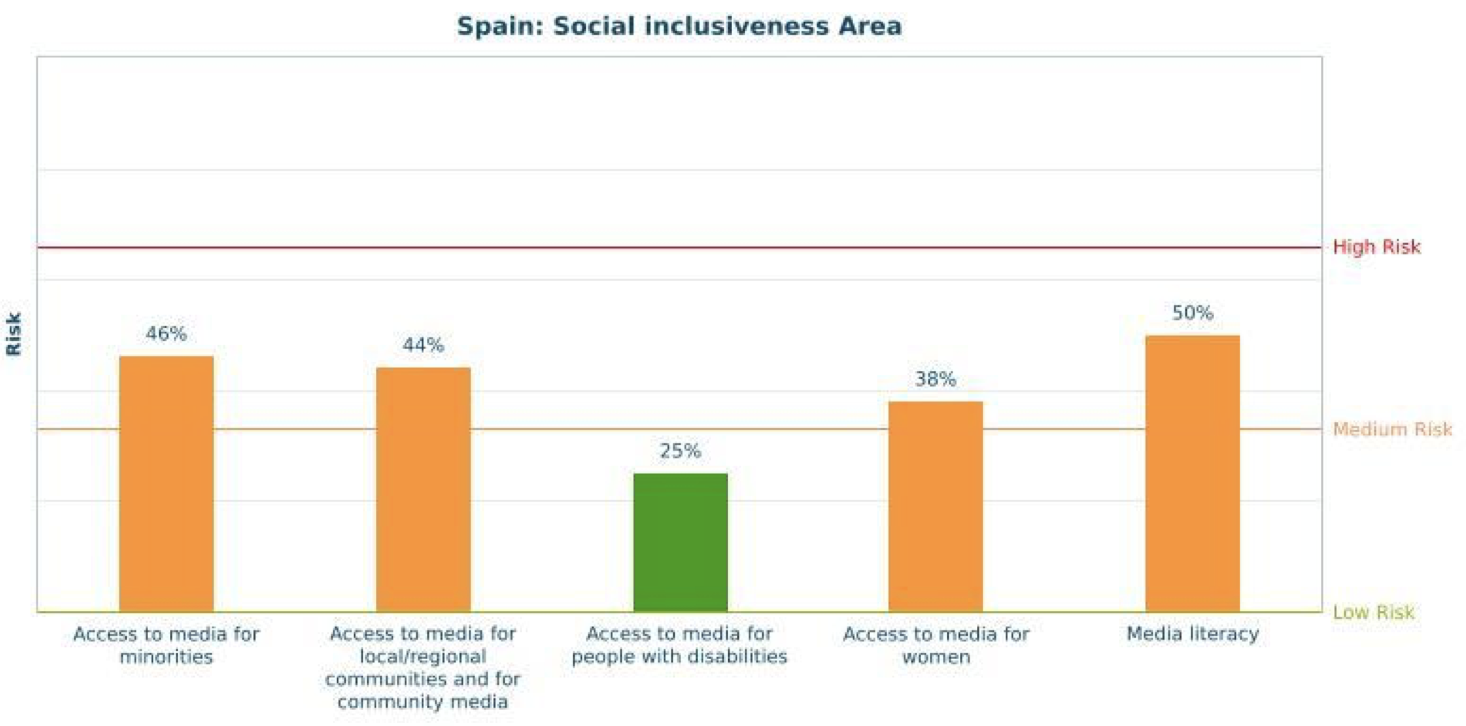

The Social inclusiveness area scores medium risk on average (41%). A considerable effort has been carried out in order to improve indicators such as Access to media for people with disabilities, and consequently the situation in Spain with respect to the recognition of the rights of physically challenged people to access to media content have improved and can be considered good.

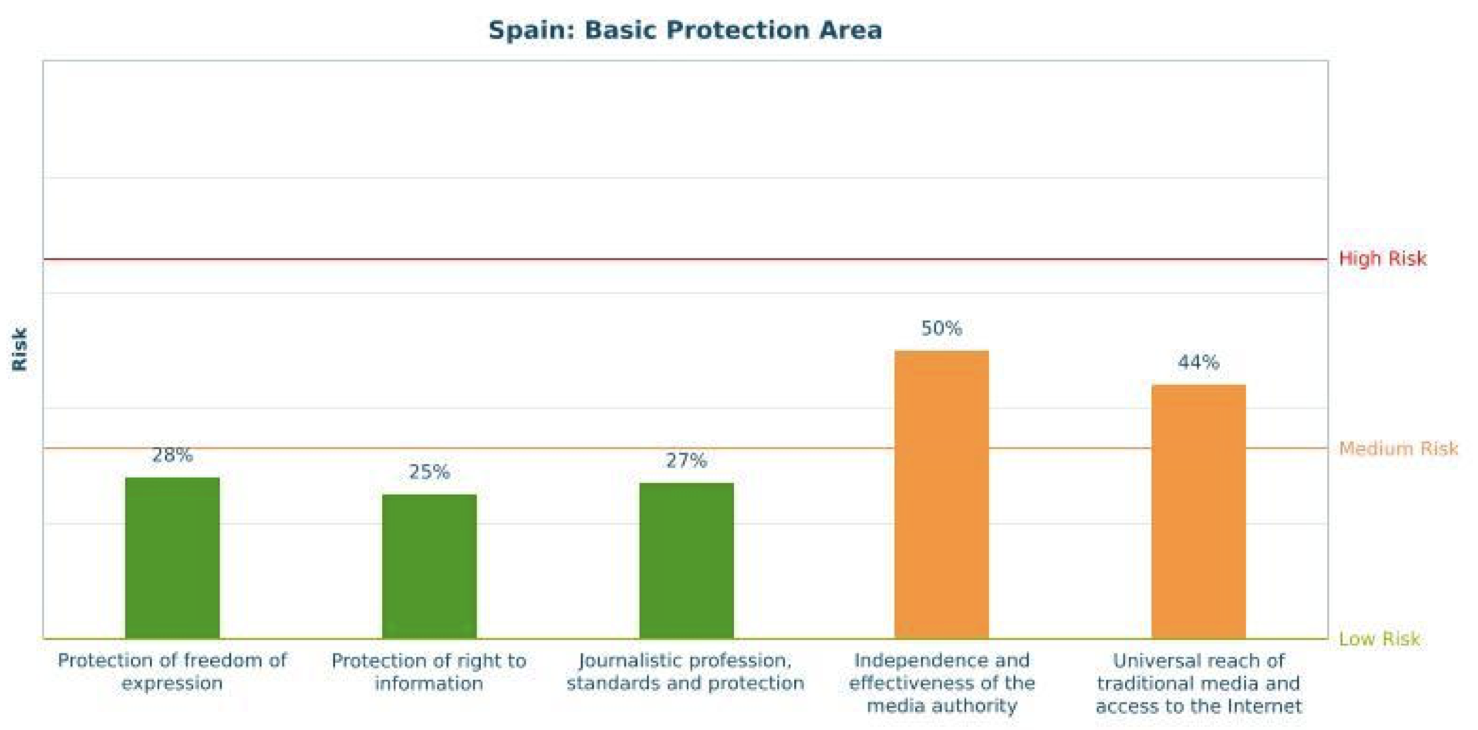

Finally, the composite score for the Basic Protection area puts Spain at the lower end of the middle risk range (35%). The evaluation of Independence and effectiveness of the media authority shows a medium risk (50%) as well as Universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet (44%). The rest of indicators score low risk.

3.1. Basic Protection (35% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The indicators within the Basic Protection vary between 25% and 50% for Spain. Of the total of 5 indicators, 3 score a low risk and 2 medium risk. It is important to underline that the three indicators score as low risk have been ranked with relatively high figures: 28% for Protection of freedom of expression, 27% for Journalistic profession, standards and protection, and 25% for Protection of right to information.

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 recognizes among the rights and freedoms of public communication, the right of freedom of expression as well as the right of information (Article 20). Every year some cases of violation of these rights have been denounced, but generally speaking we can considered that right to information and right of freedom of expression are respected in practice in Spain. However, during the year 2015 some legal reforms have generated significant controversy regarding their impact in the exercise of these rights. The reform of the Spanish Penal Code adopted in 2015 as well as the Organic Law 4/2015 about the protection of public safety, negatively affect the effective exercise of freedom of expression in Spain. Organic Law 4/2015 introduces an extensive catalogue of measures and administrative sanctions that put at risk the exercise of freedom of expression and particularly right of information. Among other restrictions and sanctions the law establishes as a serious offense the unauthorized use of images from the Security Forces.

These restrictions have been denounced both by national as well as by international associations, such as the International Press Institute, UN Human Right Committee and Plataforma en defensa de la Libertad de Información de España” (Association for the defense of freedom of information in Spain).

The exercise of journalism in Spain is open to all and barriers are not imposed to exercise the profession. To be member of a professional association is not compulsory in Spain in order to practice journalism.

Professional associations play an important role in denouncing cases of attacks or threats to the physical safety of journalists – in recent years some cases have been reported – however they have had a very limited impact in guaranteeing editorial independence and respect for professional standards. Although professional associations promote journalists’ impartiality and good practices through ethical codes, they don’t have useful mechanisms to ensure editorial independence, nor observance of ethical norms. Their work is important because it contributes to raising professional awareness, but it is not really effective enough to guaranteeing it.

Recently, conditions of journalists in Spain have worsened because of the economic crisis as well as the crisis in the media sector. Unemployment, job insecurity and low salaries are considered as the main problems facing the profession.

The risks to the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority scores as a medium risk. The National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) is the regulatory body for the sectors subject to regulation, such as the audiovisual sector. There is not a specific authority involved in regulating press or any other media sector. Besides CNMC, in Catalonia also exists the Catalan Audiovisual Council (CAC), which is the independent authority that regulates the audiovisual communication in this Autonomous Community. The CAC’s principles of action are defending freedom of speech and information, pluralism, as well as free competition in the sector.

In accordance with the law, the regulatory authority is autonomous and fully independent from the Government, public authorities and all business and commercial interest. However, the law that establishes the regulatory and competition system was perceived as an attempt by the government to devolve some regulation and competition back to Ministries in detriment of the independent bodies. There have been even formal calls from the EC to the Spanish Government to preserve the independence of the regulatory authority.

Although, the law states that the CNMC is under the control of Parliament and the members of the governing bodies must be appointed in a legal and transparent manner. Currently 8 out of 10 members have been appointed by the Popular Party, so they do not replicates the parliamentary seats’ structure. Besides, the president of the CNMC himself claimed the need for political and financial independence to act with “legitimacy, credibility and effectiveness”

The fifth indicator (Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet) ranks Spain at medium risk (44%). Coverage of PSM and broadband is almost universal; but market shows high levels of concentration.

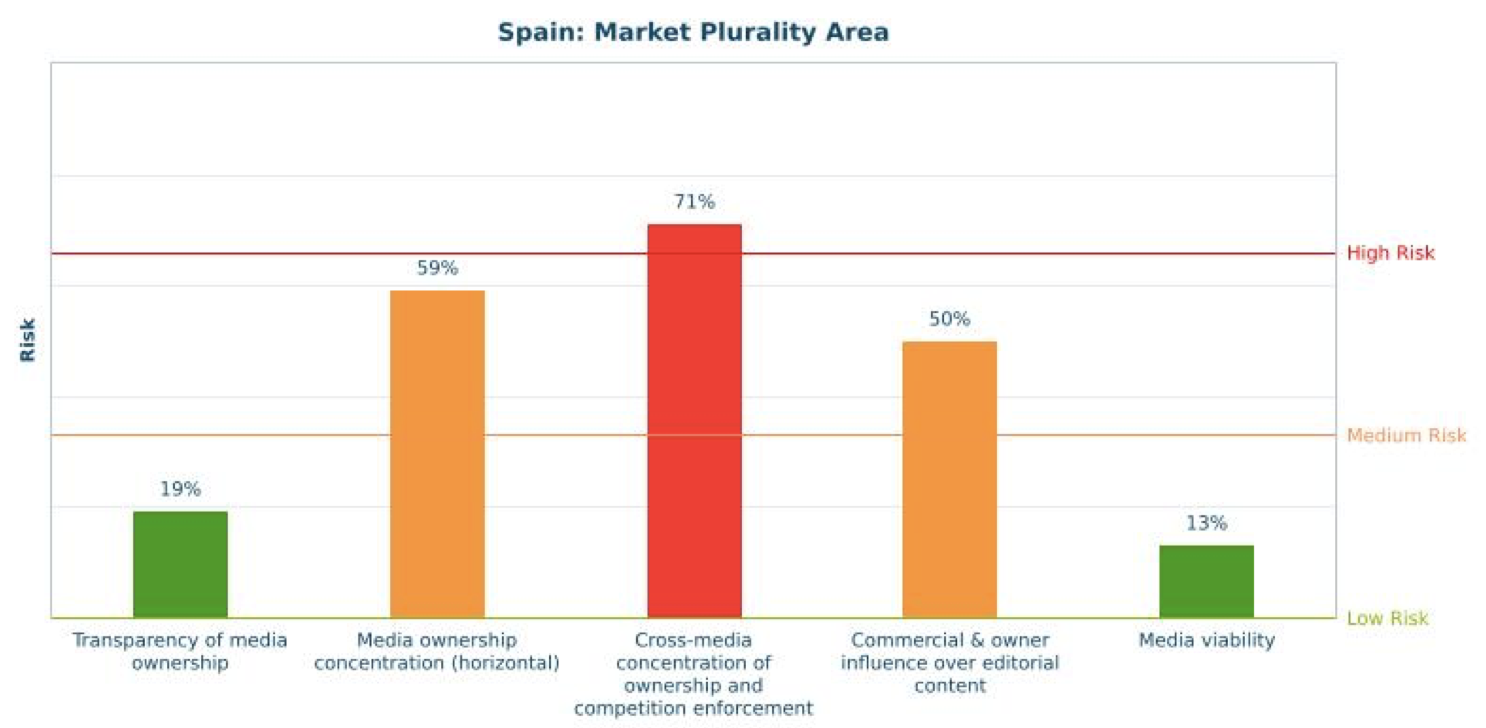

3.2. Market Plurality (42% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Of all the areas, the indicators with regards to Market Plurality score, on average, medium risk. A low risk is indicated in Transparency of Media Ownership (19%) – companies have to file their data on ownership structure to the regulatory and competition body – as well as in Media viability (13%).

The Media ownership concentration indicator presents a medium risk (59%) and the indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement shows a high risk (71%). Media ownership is regulated by the Media Act and by the National Competition and Market Commission Act, however there are no specific rules on cross-media concentration of ownership.

Although, Spanish legislation covers ownership restrictions in the audiovisual and radio sectors based on audience share and number of licenses respectively, the market concentration is high in both sectors. The Top4 TV companies – RTVE (Spanish PMS), Mediaset, Atresmedia and CCMA (Catalan PMS) – achieve 94% of the market share and 78% of audience share. Regarding the radio sector, the market share of the Top4 owners (Ser, COPE, Uniprex (Ondacero) and Radiocat XXI (RAC1) reaches 97% and the Top4 radio stations concentrate 80% of audience.

There is no specific law to prevent high levels of media ownership concentration on newspapers, therefore the legal basis for preventing horizontal concentration is the general competition act. In spite of the lack of specific legislation, there are no major ownership concentration threats, The Top4 newspaper publishers have a 30% of the market share and 36% of the readership share. Legacy newspapers counterparts take the leading positions in online news consumption. However, online pure players such as ElConfidencial.com, Eldiarios.es and Publico.es, are also relevant in this part of the market (Reuters Institute, 2016).

As previously mentioned, the indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement scored a high risk (71%). Current media legislation – including competition laws – do not establish a specific threshold or other limitations to prevent a high degree of cross-ownership between the different media. Additionally, it is also important to take into account that merger control is based only on free competition criteria (exceeding certain thresholds in terms of market share or turnover). As a consequence, a merger cannot be prohibited if it is found not to be harmful to competition in spite of being negative for media pluralism.

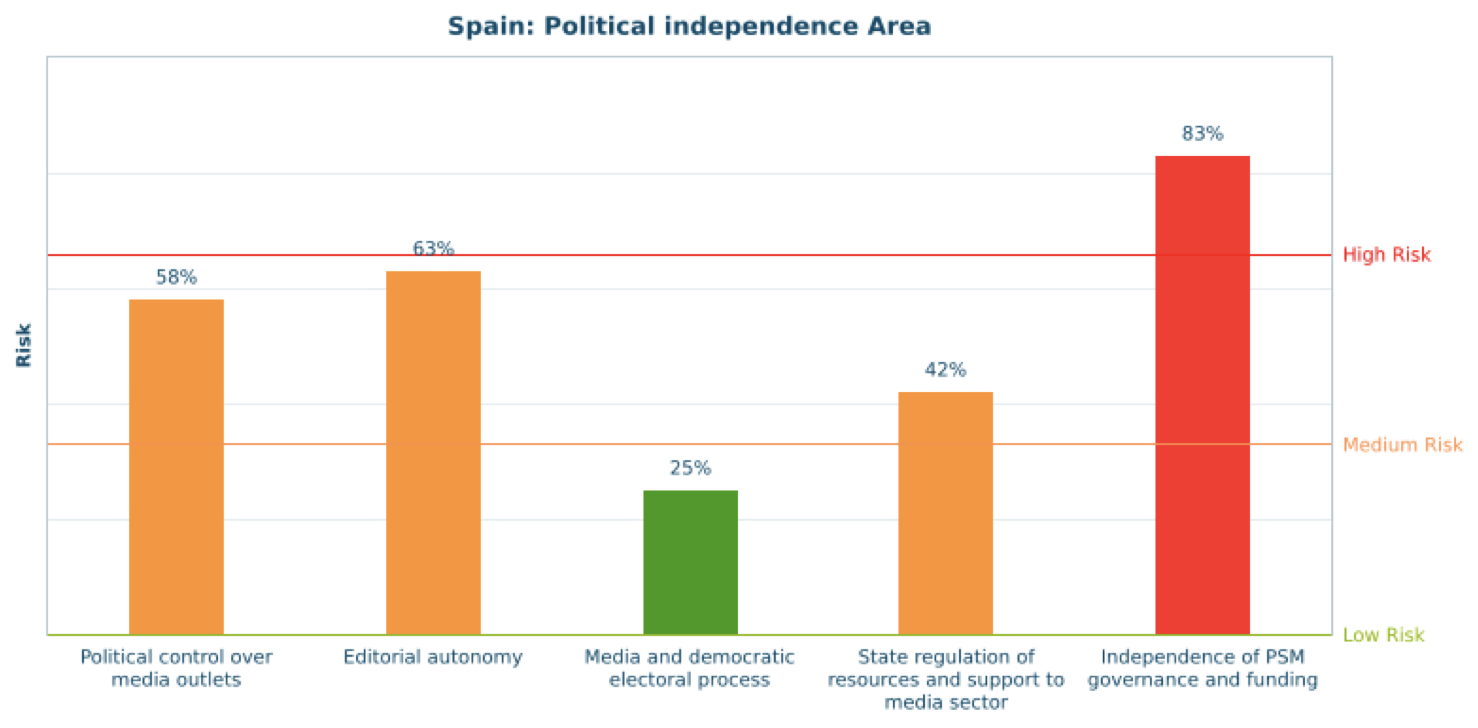

3.3. Political Independence (54% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Political independence is the area with highest level of risk, but on average still within the range of a medium band. The indicator Independence of PSM governance and funding is the only indicator that scores a high risk (83%), mainly because of the influence of Government on PSM governance by appointing the president and the board of directors of Corporación de Radio y Televisión Española (CRTVE). In 2013, the Spanish Government reformed the mechanism for electing the members of the board of directors of CRTVE, reducing from two-thirds to an absolute majority the number of parliament members needed to appoint the President of CRTVE. The previous threshold required a broad consensus among political parties and made difficult the Governmental control of the PSM. Lack of political independence is also observed among the regional public broadcasters. In regard to the PSM budget, law in Spain prescribes a fair and transparent procedures of funding. The financing model of RTVE is funded mainly through State subsidies and three different types of taxes, but the amount of the grant is decided by the government at its own discretion. In its latest annual report, CNMC considers that financing model of state-owned media is not appropriate because it does not guarantee budget stability.

Concerning the indicators assessed as medium risk: Editorial autonomy is scored with 63%, Political control over the media outlets with 58% and, finally, State regulation of resources and support to media sector with 42%. The indicator on Editorial autonomy can be considered a growing challenge in Spain. There are objective reasons to consider that there is risk of political influence in editorial content. For example, in 2013, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe expressed concerns about political pressure on public service broadcasters in some countries, including Spain. The Assembly noted, among other points, that public service broadcasters must be protected against political interference in their daily management and their editorial works; and people with clear political affiliations should not be appointed to senior management positions (Parliamentary Assembly, 2013). Both practices have been frequently denounced in Spain.

Editors-in-chief of Public Broadcasters are appointed and dismissed by the president of the state-owned company. Presidents are appointed in line with political criteria, therefore it can be assumed that the selection of editors-in-chief is also politically motivated. Several examples serve to illustrate this influence, but the most recent happened in March 2016, when the former head of the communication office of the Popular Party in Catalonia was designed as director (editor-in-chief) of TVE; and in February 2016, after the appointment of the new editors-in-chief of both Catalan public television (TV3) and Catalan public radio (Catalunya Ràdio), which have political affinity with ruling parties in Catalonia.

Political pressures also affect the private media. Between December 2014 and 2015 three editors-in-chief of three of the most important Spanish newspapers (El País, El Mundo and La Vanguardia) resigned. According to The New York Times these resignations were related to political and economic interests (Minder, 2015).

The indicator on the Political control over the media outlets scores a medium risk. There is no ownership control of parties, partisan groups or politicians over the media outlets in Spain. However, political parties, particularly ruling parties, have several mechanisms in order to influence media decisions. Three of them must be highlighted: institutional advertising, subsides, and the grant of licenses. During the last few years, denouncements regarding the irregular use of the aforementioned mechanisms have been frequent.

And last but not least, the Media and democratic electoral process indicator scores a low risk (25%). Access to the main social and political groups to PSM and private channels is guaranteed by law. During election campaigns the law also imposes rules aiming to guaranteeing political pluralism and airtime to political parties. Despite this fact, denounces of political bias and pro-government manipulation of PSM are frequent. Proportionality and plurality in the coverage of political parties during elections are not observed by private broadcasters.

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (41% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Overall, the group of indicators in the Social inclusiveness area poses medium risk. Five of six indicators score medium risk.

The indicator Access to media for minorities shows a medium risk (46%). Access to airtime on PSM channels for minorities is recognized by the law. The Spanish Constitution establishes the fundamental right of “significant political and social groups” to access the public media services and guarantees the pluralism of the society and the different languages spoken in Spain. The Public broadcasting act (17/2006) also establishes that the PSM must ensure in its programming the expression of social, ideological, political and cultural diversity of the Spanish society. Generally speaking minorities have access to airtime, however the access is not always proportional to the size of their populations in the country. Regarding the use of official languages different to Spanish (Catalan, Galician and Basque) in regions with two different languages, the number of hours of airtime can be considered low or very low.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores medium risk (44%). The Spanish law guarantees access to media platforms to regional and local media. Furthermore Autonomous Communities support local media through subsidies, usually justified for linguistic reasons, but not limited to. With regard to community media, the Media Law (7/2010) recognizes to non-profit community media the right to access media platforms, through authorization and license. However, this law has not be implemented yet because of the lack of political will. In practice, no broadcaster has been able to obtain a license, and there is no regulated process to acquire one. Consequently, existing community media can be considered as illegal.

The indicator on Access media for women scores medium risk (38%). The Spanish legal framework provides for equal rights and non-discrimination on grounds of sex, as well as equal pay and non-discrimination. Despite the legislative and political effort in this area, women are still disadvantaged in the labour market in Spain. This situation of inequality also occurs in the media sector, in which wage inequality and poor access to leadership positions of women journalists have been denounced by unions and professional associations. Furthermore two thirds of unemployed journalists are women.(APM, 2015; FAPE, 2016)

The indicator on Media literacy scores medium risk (50%). Media literacy is an ongoing issue in Spain. Overall, there have been important efforts in promoting media literacy policies, mainly through legislative changes and specific government and institutional authorities-initiated programs. However the development of media literacy policy has slowed down with the beginning of the economic crisis, with significant budgets cuts at both state and regional level. At the same time, several studies reflect the fact that on average the population has very low media literacy skills (Ferres, et al. 2011).

Access to media for people with disabilities is the only indicator of the Social inclusiveness area that scores low risk (25%). The policy on access to media content by physically challenged people has improved in recent years. The Media Law (7/2014) requires broadcasters to offer 75% of contents with subtitles and at least two hours a week with audio description. The Spanish Association of Representatives of People with Disabilities (CERMI) assesses the services for physically challenged people as generally positive. Nevertheless, they also point out that there is still room for improvement in terms of access to content and the quality of services. CERMI also suggests that the support services for physically challenged people should be extended to premium TV and to on-demand TV, and that the levels of audio description available for blind people should be improved.

4. Conclusions

The implementation of the 2016 Media Pluralism Monitor for Spain states a medium risk for media pluralism in the country. There are objective elements to consider that there is a risk that certain political decisions as well as political pressures could affect media independence and plurality. Three main challenges in regard to media pluralism have been identified.

Some recent legal reforms made by the last Spanish Government (reform of the Penal Code and the Organic Law 4/2015) are threatening the freedom of expression and journalists’ work. Reforms has been denounced by national and international associations, but it is yet to see if the new composition of Parliament after the last elections will abolish some of these legal reforms. The authors recommend the reform of some of these legal prescriptions in order to establish a more respectful legal framework towards freedom of expression.

Second, the political independence of media – public and private – is strongly questioned in Spain. There are frequent reports of pro-government manipulation of public media, both in state-owned and in regional public service broadcasting (Parliamentary Assembly, 2013; IPI, 2015). Besides, legal reforms carried out in 2012 facilitated politically motivated appointment of presidents of PSM and editors-in-chief. To recover requirements stated by the previous law for the election of the members of the governing bodies of state-owned media would allow for greater independence. In regard to private media, also greater political independence and autonomy are needed. In this sense, there is a need of legal reforms to strengthen the press councils and empower the actual existing media regulator in the country, the CNMC. Media regulator and Press Councils – which are voluntary and self-monitoring – don’t have useful mechanisms to ensure editorial independence, nor observance of ethical norms. The lack of power of these institutions offer no counterbalance to the power of private media, but a lack of control of the PSM.

Finally, we put into a single group a series of challenges related to the economic crisis in which Spanish media sector is involved. As previously mentioned, conditions of journalists in Spain have worsened in the last years, and 2016 has not been an exception. Unemployment, job insecurity and low salaries are considered as the main problems of the profession; all of them are serious threats for journalists’ free expression and independence. The access to media of women is also at risk. Wage differences between men and women exist, whereby women receive lower wages for similar work; and the women are underrepresented in management boards, both in public and private media. Although there has been an important progress on the issue of equality in Spain, and the legal framework provides for equal rights and non-discrimination on grounds of sex, the existing legal framework on gender equality has not been yet fully implemented. Real implementation of gender equality plans in the media sector should be a priority for professional associations, as well as for the political authorities themselves.

References

AEDE (2016) Libro Blanco de la Prensa 2015. Madrid: Asociación de Editores de Diarios Españoles

AIMC (2016). Estudio General de Medios. Resumen general de resultados. Madrid. AIMC.

APE (2015). Informe anual de la profesión periodística 2015. Madrid. Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid.

Eurostat (2016) Europe in figures – Eurostat yearbook. Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Europe_in_figures_-_Eurostat_yearbook

FAPE (2015). FAPE alerta sobre la desigualdad salarial y el escaso acceso a los cargos directivos de las mujeres periodistas. Madrid: Federación de Asociaciones de Prensa de España. https://fape.es/la-fape-alerta-sobre-la-desigualdad-salarial-y-el-escaso-acceso-a-los-cargos-directivos-de-las-mujeres-periodistas/

Hallin, D. and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University

INE- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2016a). Cifras de población. Madrid: INE. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/categoria.htm?c=Estadistica_P&cid=1254735572981

INE – Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2016b). Encuesta de Población Actica. Madrid: INE. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176918&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976595

International Press Institute (2015). The State of Press Freedom in Spain: 2015. International Press Institute . https://www.access-info.org/wp-content/uploads/IPISpainReport_ENG.pdf

Parliamentary Assembly (2013) The state of media freedom in Europe. Resolution 1920 (2013). https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=19474&lang=en

Reuters Institute for the Future of Journalism (2016) Digital News Report 2016. Spain. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2016/spain-2016/

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Pere | Masip | Professor | School of Communication and International Relations Blanquerna – University Ramon Llull | X |

| Carlos | Ruiz | Professor | School of Communication and International Relations Blanquerna – University Ramon Llull | |

| Jaume | Suau | Lecturer | School of Communication and International Relations Blanquerna – University Ramon Llull | |

| Ángel | García Castillejo | Lecturer | School of Communication and International Relations Blanquerna – University Ramon Llull |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Victor | Sampedro | Professor | Universidad Rey Juan Carlos |

| Joan | Barata | Legal Consultat | CommVisions |

| Julia | Lopez de Sa | Assistent Director | CNMC |

| Hugo | Aznar | Professor | Universidad CEU-San Pablo |

| Albert | Sáez | Journallist

Deputy editor |

El Periódico de Catalunya |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/