Slovenia

Download the report in .pdf

English – Slovenian

Author: Marko Milosavljevic

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016, under a project financed by a preparatory action of the European Parliament. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Slovenia, the CMPF partnered with Marko Milosavljevic (University of Ljubljana), who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

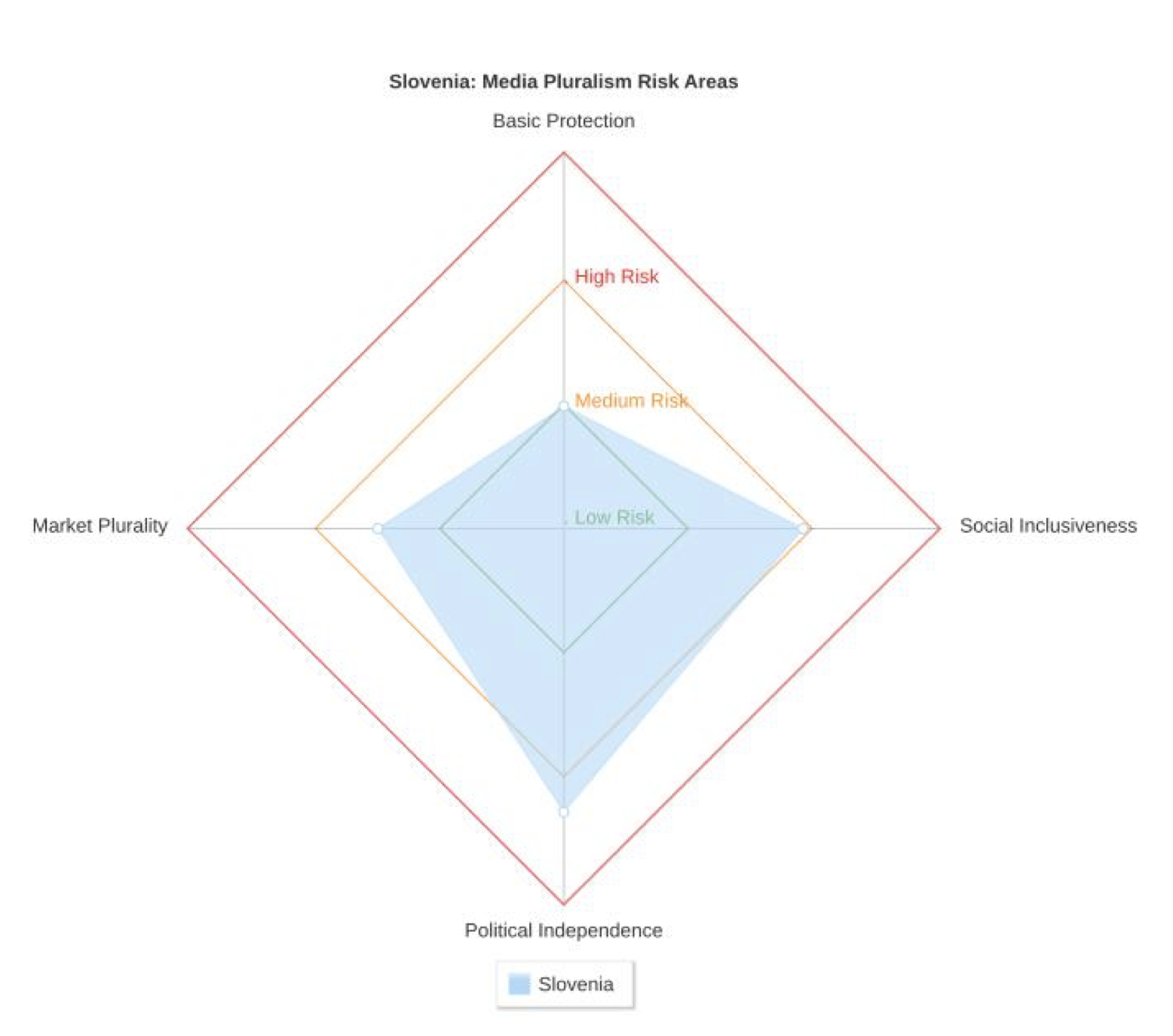

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Slovenia borders Italy, Austria, Hungary and Croatia and it has a bit more than 2 million inhabitants. It was part of former Yugoslavia until 1991, when it gained its independence. The official language in the country is Slovene. There are three officially recognised minority groups: Hungarian, Italian and Roma group. However, also other officially non-recognized minorities from the former Yugoslavia live in the country, such as Serbs, Bosnians and Croats.

The functions of the Slovenian media landscape and the terms of state ownership and political control of the media have been influenced by the economic and political restructuring of the former socialist society. In the independent years there has been a typical political left wing / right wing divide, with some new central liberal and further left and right parties entering the arena in the recent years. Currently, the country is ruled by a political party of the centrum, which won the elections as a newly formed modern party that follows a strong moral code, social state and strives to eliminate corruption. However, the measures, they have been executing in the last years are more similar to those executed by more conservative parties, including setting a barbed fence on the country’s border and deporting refugee families in great distress.

The government also undertook changing the Mass Media Act, which has been a procedure lasting for a few years already with a public debate on different topics, a big number of them on the implementation of music quotas. The main media regulatory bodies are the Media Inspector and Directorate of Media within the Ministry of Culture, which supervise the implementation of the Mass Media Act and the Agency for Communication Networks and Services of the Republic of Slovenia. Media concentration is high and regulatory bodies usually do not have the autonomy or drive necessary to change that, even though the media legislation is in some fields restrictive. Media ownership – especially in the recent years – has been changing with a fast pace. Majority of the print outlets have been resold to new owners, due to poor financial conditions, bad management and the need for so called restructuring. In this process a lot of journalists were laid off. The only public broadcaster is the Radio-Television of Slovenia (RTV), the main private broadcasters are Pro Plus channels, TV3 and Planet TV.

The economic crisis in 2008/2009 affected the Slovenian economy as a whole. The media sector in particular has demonstrated the weaknesses of the existing market model of media financing, particularly when faced with weak or slow reactions from regulatory authorities. The continuing crisis – has left most of the media companies weaker and more exposed to different pressures, including both political and advertising pressure from owners and other actors in society.

Combined with the rise in internet usage, there have been a lot of changes in the media landscape, especially with daily print rapidly losing its circulation and readership. From the technical point of view, digitalization has been quite painless for Slovenia, as was the spread of digital media. Almost all of the population is covered by broadband, while around 70% have a cable and fixed broadband access at home[2]. Over half of the advertising income goes to television, while print media share is around 3%[3]. Data from 2014 showed that 23% of the whole population used internet to watch television on daily and weekly basis, while another 19% used it less often (on monthly basis)[4].

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Media pluralism is in general, in quantitative terms, in a good state in Slovenia. Regulations for ensuring media pluralism are mostly clearly defined by laws and legal acts, and there are authorities that monitor compliance with the rules. However, implementation is often weak and monitoring and sanctioning is ineffective and slow. There are some very high risks in certain areas of media pluralism, namely regarding media literacy, politicization of control over media outlets, state advertising, independence of PSM governance and funding and independence of news agencies and other traditional and digital content providers.

Freedom of expression in the country is at a medium risk, violations can be demonstrated mainly via the prosecutions of journalists who disclose classified documents or data in the public interest and also online. Online is very poorly regulated. Concentration of media ownership in print, radio and audiovisual media is also at a medium risk. The Top4 owners of audiovisual media almost completely own the market, while newspapers and radio channels have in the past years been in the process of intense mergers and takeovers, which were not prevented by the relevant authorities.

Political bias in the media is also at a medium risk. The Radio and Television Corporation of Slovenia Act imposes rules on fair and balanced representation of political viewpoints on PSM channels, however these rules can sometimes cause an unfair representation, because some voices are included just on the basis of being balanced, without minding the content.

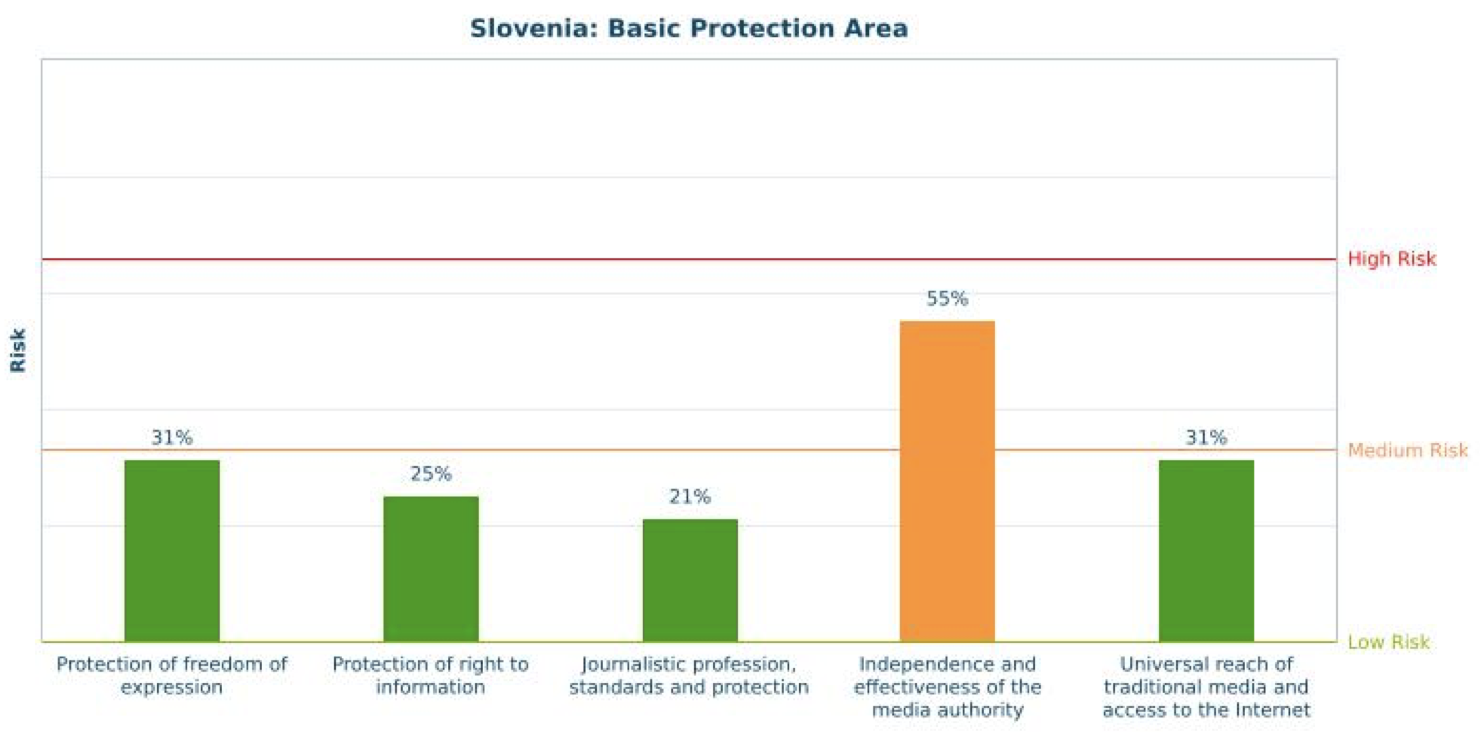

3.1. Basic Protection (33% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

As regards the legal protection of freedom of expression, Slovenia has almost a medium risk (31%). Although it has effectively implemented international regulatory safeguards, legal standards on restrictions upon freedom of expression are not always followed. Concretely, the system for providing legal protection of freedom of expression as a sub-variable in this area presents medium risk. It is semi effective: the regular remedies and instances are all costly and have long lasting procedures and can also be misused by politicians. Cases of violations of freedom of expression have been noted mainly in the prosecution of journalists who disclosed classified documents or data that were in the public interest. Violations of freedom of expression online have also been noted , especially regarding freedom of expression on social media. In one example a TV journalist was fired due to her comments on Twitter about a TV? Show. A PR person was fired by his company due to his comments on government politics (not related to his company). There is a low risk considering filtering or monitoring online content in an arbitrary way. Defamation, slander, calumny, malicious false accusation of crime and insult are criminalised.

Protection of right to information presents a low risk (25%)and is explicitly recognized in the Constitution, as well as in laws. Restrictions to freedom of information on grounds of protection of personal privacy are not narrowly defined; however they are mentioned in the Constitution. Appeal mechanisms for denials of access to information present a medium risk. Although they are in place and decided by the Information Commissioner, the procedures have little effective control, but in general there are not many cases of violations of right to information in Slovenia, although obtaining information can be quite a long process for journalists or the public.

The Journalistic profession, standards and protection indicator reached a low risk (21%). Access to the profession is open on paper as well as in practice. Journalists are represented in three different professional associations, although these are only partially effective in guaranteeing independence and respect for professional standards, as they do not have real levers of power. As for protection of journalists, as a sub-variable in this area, there is a medium risk, due to some rare cases of attacks or threats to the physical safety of journalists. In general there is a high risk in the working conditions of journalists due to bad economic circumstances. As for editorial content, the Code of Journalism Ethics and the Mass Media Act officially prohibit commercial parties from influencing editorial content. Protection of journalistic sources is explicitly recognised by the Mass Media Act, but there have been some infringements recently. The working conditions for journalists present a high risk, as there are a lot of irregularities in payments and high job insecurity.

As regards the independence and effectiveness of the media authority, the risk is medium (55%), but only slightly below high. While there are legal guarantees re the independence of the media authority, the appointment procedures are not satisfactory (quite loose and therefore not always effective in safeguarding independence). The highest key function of the authority is named by government personnel, which may result in a strong political bias at the head of the organisation. The same goes for appeal mechanisms – they can be very slow, inefficient and easily delayed, especially once the disputes reach higher courts. The authority’s powers are not always used in the interest of the public, as there were reports[5] on the potential abuse of its power for personal reasons. The government can at times arbitrarily overrule decisions by the media authority. Nevertheless, the media authority is generally transparent but does not publish information about its activities on a regular basis.

Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet presents a low – almost medium – risk (31%). The former is guaranteed by law and the public broadcaster provides good coverage of the territory and the population with signal of its TV and radio channels. There are no official data on the coverage of the PSM though. But as regards the internet, 73 % of the rural population is covered by broadband. According to the Point Topic research for the European Commission, in Slovenia most rural households were not able to access the high-speed services. DSL services covered less than 70% of the households in Slovenia in 2012, placing it well below the EU average for coverage. The TOP 4 ISP’s share 88 percent of market shares in the country.

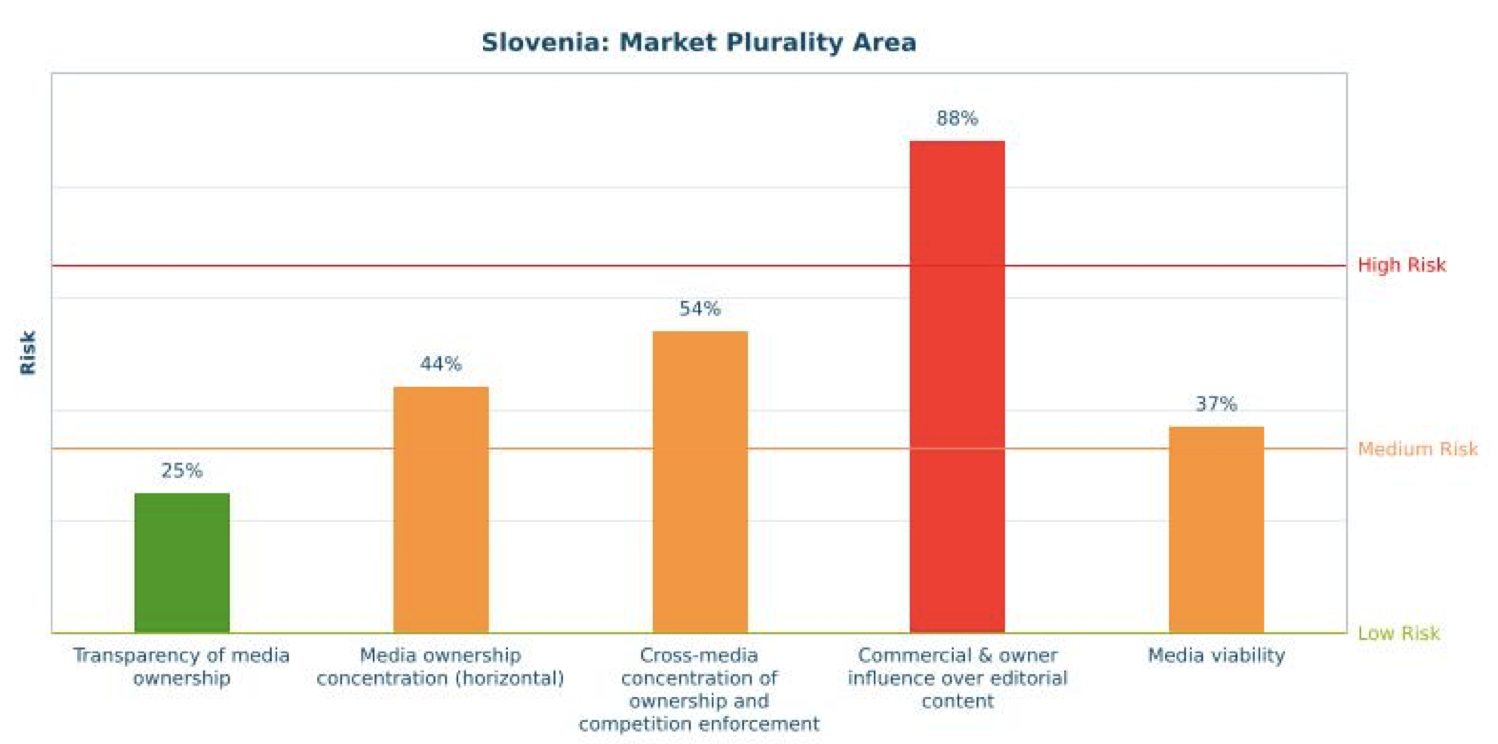

3.2. Market Plurality (50% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Transparency in media ownership presents a low risk (25%). Media companies have the duty to disclose information on their ownership structures to the Ministry of Culture and it is published in the Media Register, which is accessible to everyone and checked by the regulator but still does not show the ownership structure for every media. A lot of times the media ownership structures get very complex and the information the register is collecting is just not detailed enough to reveal the real owner, who is hidden behind a number of the so called paper companies. Among others, owners use them to hide the scale of their media monopoly.

Media ownership concentration (horizontal) is under medium risk (44%). Media legislation contains a specific threshold for ownership concentration (20%) after which the approval of Ministry of culture is needed in order to prevent a high level of horizontal concentration of ownership. There are several public bodies that actively monitor compliance, including the ministry, which also has sanctioning powers. Violations still happen as the ownership is easily hidden using paper companies. The radio sector has seen an intense process of concentration and takeovers in the past years. As for newspapers, the authorities have also been quite ineffective in preventing controversial takeovers. Internet content providers are not mentioned in the law regarding ownership and concentration.

A high level of horizontal concentration of ownership can be prevented through the provisions of the Mass Media act, but there is still need for a stronger control and more decisive control of relevant authorities. Top 4 owners almost completely control audiovisual market in Slovenia.

Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement has started to present a bigger risk (54%) in the recent years. Media legislation contains measures to prevent a high degree of cross-ownership between the different media and there are monitoring bodies designated to monitor those provisions. They can refuse giving a license, although these powers are not always used. Specifically some recent cases show that cross-media concentration is developing more, although it is officially prohibited by Mass Media Act, showing inefficiencies or passive (on purpose) behaviour of regulatory bodies. The issue was particularly raised when a telecommunications company Telekom Slovenije was allowed to establish a TV station Planet TV in 2012.

There is no reliable? data on the market share and relevant media-related revenues in relation to all media actors. The issue is also whether to include PSMs in these measurements as their income mostly overshadows all other media actors and show a different picture if not included in the overall market analysis. There is also no authority overseeing whether state funding has exceed what is necessary to deliver the public service or hearing relevant complaints.

There are no provisions in the Media Act concerning Commercial & owner influence over editorial content, and there is no specific act that includes journalist’s right for protection in cases of changes of ownership or editorial line. The Union of Slovenian Journalists offers free legal support, professional associations also offer support, however not everybody is a member. There are also no regulatory safeguards, including self-regulatory instruments, which ensure that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief are not influenced by commercial interests. However, there is an article in the Code of Ethics, which states that journalists should ‘’avoid real or perceived conflicts of interest’’ and the Mass Media Act states that journalists and hosts should not be connected with advertising. There is a legal prohibition of advertorials; however the law is not effectively implemented, as there are many recent cases of advertorials and subliminal advertising, mostly in print and online media. The risk of commercial influence on editorial independence? is therefore high (88%).

There is no consolidated data on revenues of the audiovisual, radio or newspaper sector, includind expenditure for online advertising. The media organizations are developing some new sources of revenue, however not always successfully. A lot of new online media outlets are trying to use crowdfunding as a source of income and offering free content. Established print media outlets are focusing more and more on online and creating a viable model of subscriptions for specific content (such is Dnevnik, Delo, Mladina, Večer, Slovenske novice). Some limit free access only to specific content (commentaries, reviews, longer articles but not everyday news), while some limit free access to everything except for short news for a week and then make it free of charge. There were also attempts to create a unified payment system called Piano; however it did not include all of the bigger media houses. In the end it brought a small number of subscribers and a very low income for the media involved (as is explained in the article named Piano in Slovenia: little music for little money[6]). By law the state should provide funding for media; however in practise the support schemes failed to facilitate market entry or to enable media organizations to overcome financial difficulties, as the amount of funding was very small. Mostly new media can apply for temporary grants and public calls, which usually get a lot of applications, so only few are contemplated. The indicator for Media viability scored medium risk (37%).

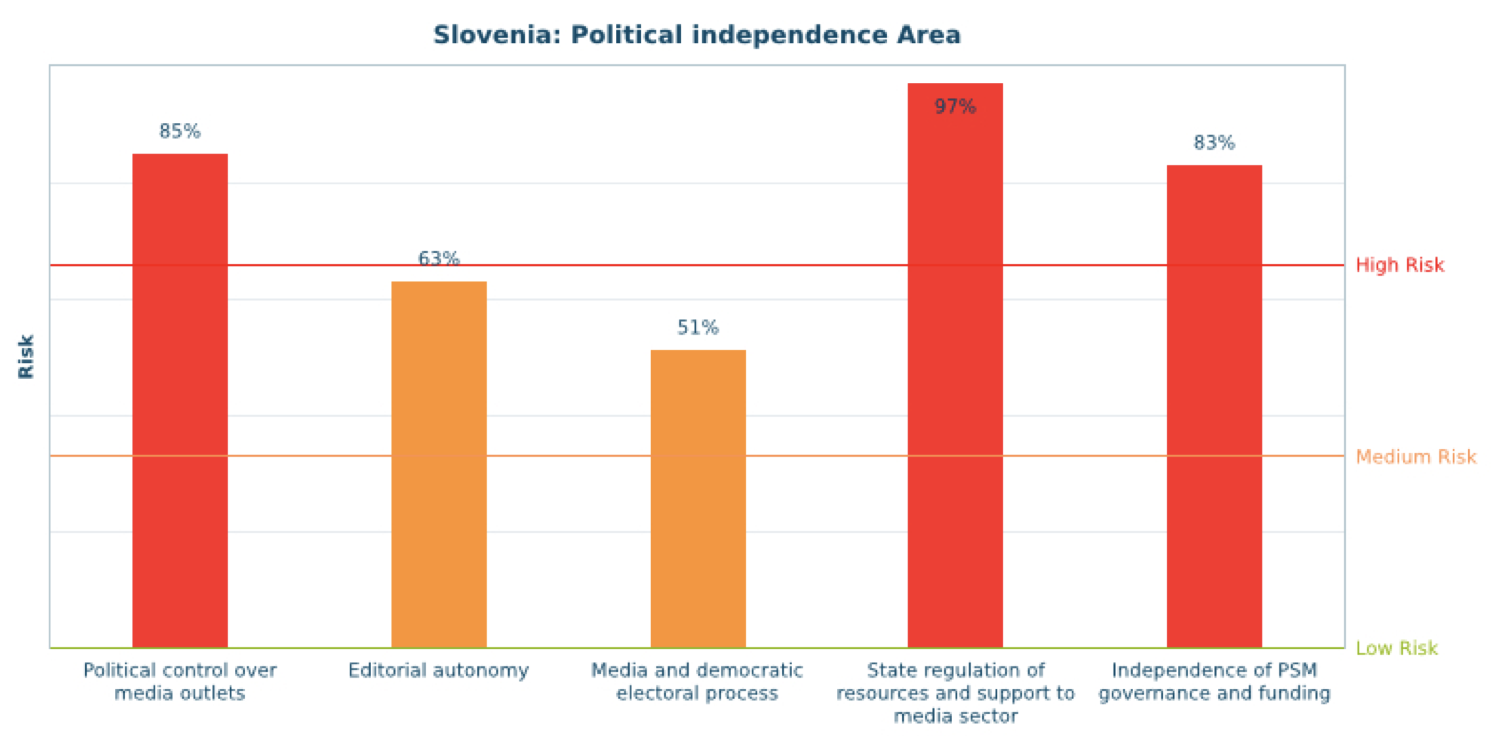

3.3. Political Independence (76% – high risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicator on Political control over the media outlets presents a high risk (85%). The law does not regulate a conflict of interest between owners of media and the ruling parties. Especially in the local areas this conflict is very present: a lot of local small newspapers and publications are connected with major political parties. The Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) of the current opposition is most present, as it very openly manages (members are co-owners) a TV station Nova24TV and has a strong party editorial support of at least two print and online political magazines (Reporter, Demokracija). All of them are national level media.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a medium risk (but nearly high – 63%). There are no common regulatory safeguards to guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief and there is occasional interference in these procedures in practice. A known case happened at newspaper Delo in 2005, when a member of the SDS party became chairman of the newspaper’s supervisory board, which first changed the president of the board, who later changed the editor-in-chief, who dismissed all the other editors[7]. There have also been some cases of direct political influences on editorial content. The general Code of Journalism Ethics functions as a self-regulatory mechanism, however it is non-obligatory. There are no sanctions following incorrect usage of the code, there is no control body, which would have real powers and it does not mention editorial independence. As a self-regulatory measure it is not efficient. The largest media outlets don’t have any of their self-regulatory measures implemented to guard editorial independence.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a medium risk (51%). The media law does impose rules aiming at fair representation of political viewpoints in news and informative programmes on PSM channels and services; however, there is no designated body with effective enforcement powers that would overlook this representation. The “fair and balanced” approach by PSM is often very mathematical, looking for one representative of “the right” and one of “the left”, or “pro” and “contra”, which leads to relativism of issues. The PSM has very precise rules regarding the representation of the different groups of political actors. There are differences in coverage of parliamentary parties and non-parliamentary parties, which can lead to problems when a new party or movement is running the campaign, even if they are very popular in public-opinion polls. There are no laws to guarantee access to airtime on private channels and services for political actors during election campaigns. No law also prohibits or imposes restrictions to political advertising on PSM during election campaigns to allow equal opportunities for all political parties. There are no restrictions on allocation of advertising space. The conditions and prices are set. However, the stronger political actors can obtain more space than the new smaller ones as they have a better and more stable financial background, which in the end does not result in an equal territory for all political parties.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to media sector scores the highest risk in this area, and in general (97%). There is a regulation on the allocation of radio frequency bands in Slovenia, which states that the allocation is done based on the yearly regulation of plan for frequency allocations. However, the provisions of the law do not ensure transparent allocation and so the allocation in practise is not transparent. There are no direct and transparent rules on the distribution of direct subsidies in the media sector, neither on the distribution of state advertising to media outlets, so both of these fields present a high risk. Direct subsidies are mostly given out in the form of public grants and calls. There is a main annual public call for co-financing media programmes, of which criteria are known, but the allocation itself is not transparent enough and it can easily happen that a certain media outlet is given priority over the other based on personal relations. There is no regular reporting on the distribution of state advertising, however, there has been a slight decrease in the practise of non-transparent distribution, due to the further privatisation of state owned media companies in the 2010s. There are no indirect subsidies for the media sector.

Independence of PSM governance and funding presents a high risk (83%). Although the RTVS Act states that voting by the Programme Board shall in all matters be made public, the final appointed constellation is not that fair, mainly due to political interference. Out of 29 members, 21 are appointed by the National Assembly, while only three members are appointed from themselves by employees of RTV Slovenia. While members of boards chosen by political parties should take into account the relative representation of political parties in the National Assembly and they should not be members of official bodies or hold positions in political parties, those are not strict enough regulations to provide for independence of PSM boards. Although the government doesn’t directly decide on the wages of PSM employers, wage levels are influenced by the austerity measures the government has been implementing in recent years – reducing salaries of civil servants or generally in the public sphere. No measures for transparent and objective procedures to allocate funds to PSM are prescribed.

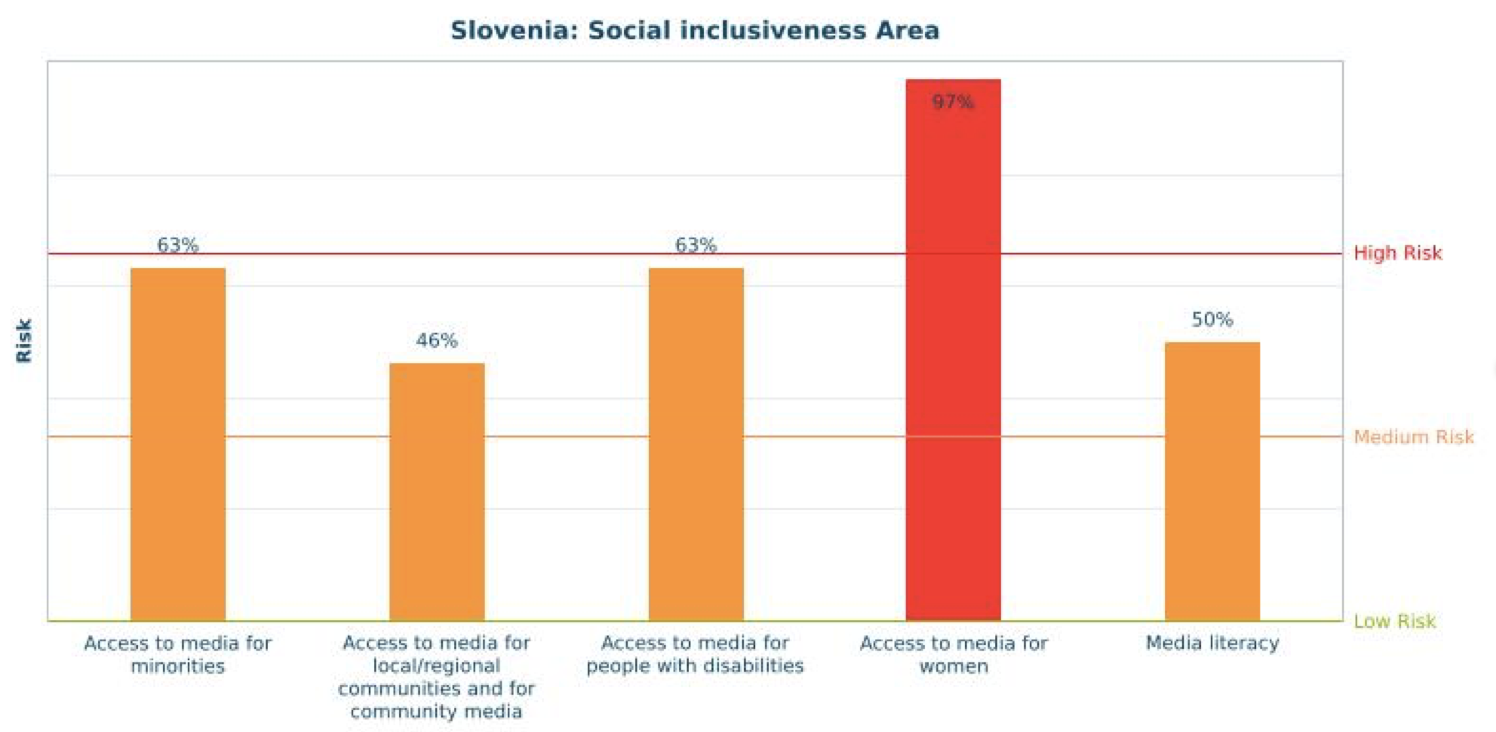

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (64% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator Access to media for minorities scores medium risk. The Constitution of Slovenia protects two traditional national minorities, Italian (0,3 %) and Hungarian (0,1 %), and the Roma community. A number of big ethnic groups in Slovenia are not recognized as national minorities, namely the Croats (1,8 %), Serbs (2 %), Muslims and Bosniaks (1,6 %). Access to media for minorities is guaranteed on the PSM by the Radio and Television Corporation of Slovenia Act,In practise, most of the minorities have adequate access to airtime but there are some significant exceptions. These exceptions are represented by minorities, which do not have an official status as a minority in our country, especially ethnic minorities from the former Yugoslavia, which are in an unregulated situation. Despite their size, they do not enjoy any of the rights the official minorities hold, which puts them in an unequal position without harming official statistical representations of protecting national minorities. Programming hours on audiovisual media and radio channels dedicated to minorities are overall not proportional to the size of their population in the country. There is no official data on the number of newspapers dedicated to minorities and the proportionality with the size of the minority, however the country team estimates that the number is not proportionate.

The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores medium risk. Although the access to both community and local/regional media is guaranteed by law and with two designated bodies monitoring compliance with sanctioning powers, there is no data on their effectiveness as the law is in the process of amendments. The law does not guarantee independence of community media. As for access to media of local communities, the PSM is not obliged to have a minimum proportion of regional or local communities involved, nor to have a balance of journalists from different geographic areas or to have news in local languages. In practice, the PSM regularly broadcasts local news programmes but the number of local correspondents has been reduced in the last few years. .

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk. The state policy on access to media content by people with physical challenges is underdeveloped. The general media law is not precise enough and not up-to-date with changes in the media landscape, so especially private media channels are not committed to assuring access to their content for audiences with disabilities. The exception here is only the PSM, which is obliged to more developed policies in the Radio and Television Corporation of Slovenia Act. Subtitling and sound descriptions are available at public service television channels in different timings. However, a full service for people with hearing or sight impairments is still not available. Audio descriptions for blind people are not available and support services such as subtitles, signing and sound descriptions are available only on irregular basis or in the least popular scheduling windows for people with hearing impairments.

The indicator Access to media for women scores very high risk (97%). Although there is an Equal Opportunities for Women and Men Act[8], there is no segment of it covering the media. The PSM does not have any kind of gender equality policy and women are also underrepresented in the PSM management structure with only about 20% of the members of the programme board being women. There is no other official data on representation of women in media.

The indicator Media literacy scores medium risk. Media literacy is often mentioned in different government documents related to the media, but there is a lack of consistent policy and programmes. The subject is present to a limited extent in formal and non-formal education. Media literacy activities are limited to the capital of Slovenia and some bigger cities. IT literacy activities are limited to certain groups of people, such as the older generations or students.

4. Conclusions

Slovenia is an example of a country where many aspects of media pluralism, including large numbers of media outlets in different sectors with frequently different, unrelated owners, are fulfilled. However this quantitative aspect is very often not supported from a qualitative aspect: the important issue of diversity of radio programming, for example, still exists – despite large number of radio stations, most of them offer similar if not outright identical? programming and content, with very little variety of genres, specialization and other content, particularly types of music, which demand more attention from the listener.

This problem of diversity persists in other media sectors as well, but there are also many others, particularly issues of economic sustainability of qualitative content production and journalism. Public interest interventions by the state and its institutions are still mostly limited to the political aspects of “pluralism” which is very often defined or perceived almost exclusively in terms of political frictions and split between “left-wing” and “right-wing” politics.

Slovenian media policy needs to focus on the issues of short-term and long-term support of qualitative media and quality journalism that foster a critical and independent media in Slovenian society that could benefit the quality of political process and quality of life in general.

This includes (but is not limited to):

- immediate measures by the Ministry of Culture and other potential ministries (for work, for example) to allocate funds and implement (new) measures for stable employment of journalists;

- tax reductions for media or content that is particularly in the (defined) public interest;

- transparent financial structure in the case of takeover or merger attempts;

- same criteria for quotas of domestic production for Slovenian broadcasters / AVMS and for broadcasters / AVMS that officially originate from outside of Slovenia, but target Slovenian market (with Slovenian subtitles and Slovenian advertising) which relates also to the updates of European AMMS Directive that is in the process of public discussion and new amendments.

Annex 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Marko

|

Milosavljević | Professor/ Researcher/

Consultant |

University of Ljubljana | x |

| Romana | Biljak Gerjevič | Assistant Researcher | University of Ljubljana | |

Annex 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Mojca | Pajnik | Researcher/ academic | University of Ljubljana/Mirovni inštitut |

| Tomaž | Drozg | CEO | Adria Media / Chamber of Commerce |

| Blaž | Petkovič | Journalist | Daily Dnevnik/Journalistic Association |

| Tanja | Kerševan Smokvina | Regulatory expert | AKOS – Agency for Communication Services |

| Cene | Grčar | Legal expert | Pro Plus TV/Association of Broadcaster |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Broadband Coverage in Europe in 2013: https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/cf/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=8239.

[3] European Journalism Centre: https://ejc.net/media_landscapes/slovenia.

[4] Media use in the European Union 2014: https://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb82/eb82_media_en.pdf.

[5] Delo 2016, 9th of December: https://www.delo.si/novice/slovenija/apek-si-drazbo-frekvenc-predstavlja-drugace-kot-vsi-ostali.html.

[6] Media watch: https://mediawatch.mirovni-institut.si/bilten/seznam/43/splet/.

[7] Mladina 2012, 28th of September: https://www.mladina.si/116278/v-napad/.

[8] Equal Opportunities for Women and Men Act: https://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO3418.