Download the report in .pdf

English – Romanian

Authors: Marina Popescu, Adriana Mihai, Adina Marincea

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Romania, the CMPF partnered with MRC – Median Research Centre, Bucharest, who conducted the data collection, annotated the variables in the questionnaire, and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Romanian team organized a stakeholder meeting on 27 April 2016 at the European Commission Representation in Romania. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

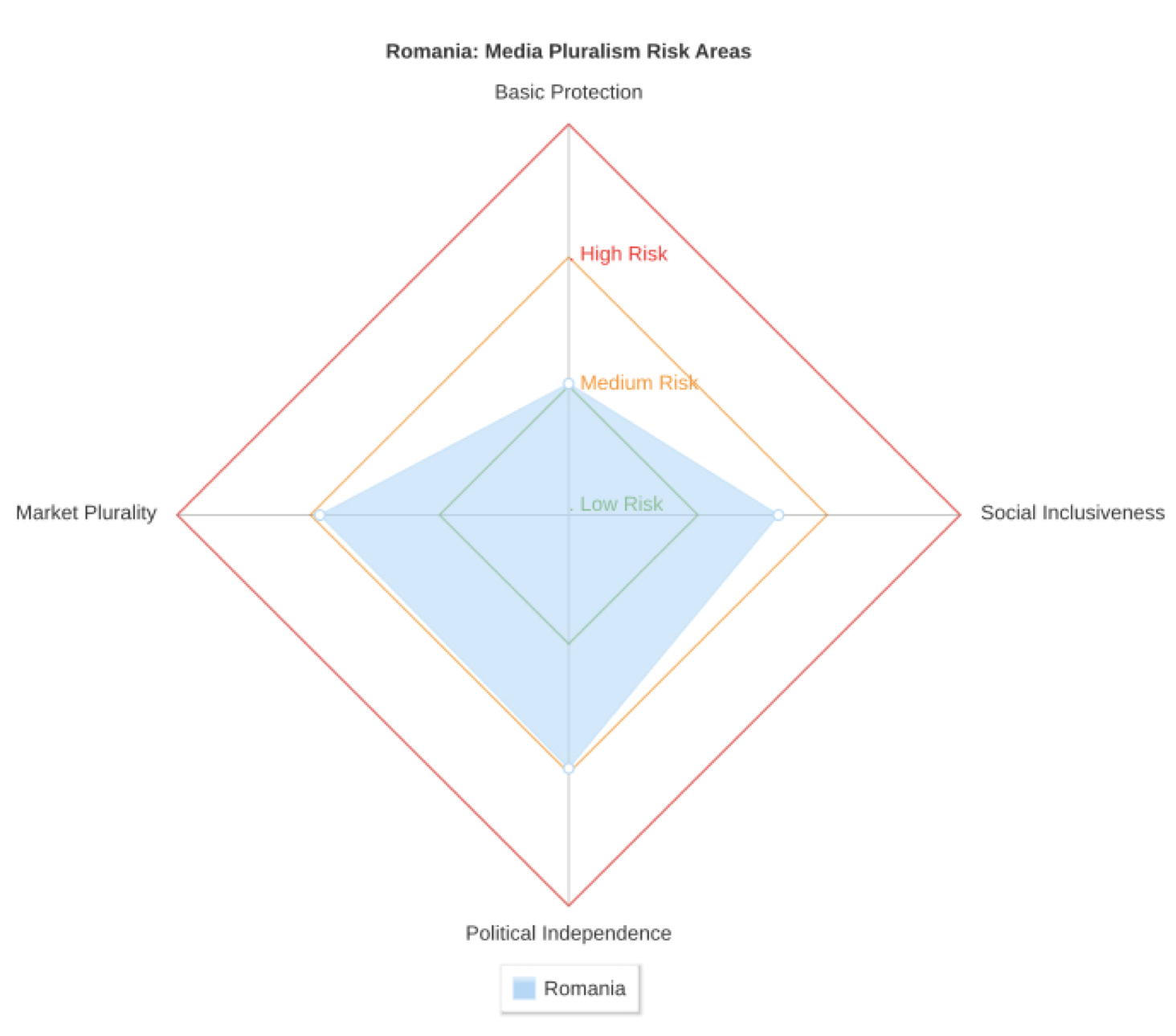

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0% and 33% are considered low risk, 34% to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67% and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

A former communist country situated in South-Eastern Europe and an EU member state since 2007, Romania has a population of 20,121,641 (INS 2011), which makes it the seventh most populous state in the EU. Yet it is also the second poorest in the EU, with a GDP per capita that is only 57% of the EU average (2015, Eurostat), with the second highest proportion of the population at risk of poverty and social exclusion in the EU (37.3%), the highest incidence of in-work poverty (18.8%) and significant income inequality (a Gini coefficient of 34.7). The structural challenges are enhanced by an aging population, low labour market activation, in spite of lower unemployment than the EU average, and low educational attainment. The PISA educational achievement scores are well below the OECD average, and school dropout rates are 19%, compared to the EU average of 11%. Moreover, state capacity is diminished by state capture, a short supply of impartial institutions, reduced administrative efficiency, and an ineffective and slow judiciary.

There is a high degree of political polarization in Romania, but mostly on symbolic issues. Party competition cannot be characterized as programmatic (Pop-Eleches, 2008), as it is low on policy content and tends to be characterised by the demonization of the opposing side, including mutual accusations of corruption or abuse of power (Chiru, 2015). Despite this polarization and mutual distrust, which fuels divisions and low trust in the parties and the system among the citizenry, since 1990 virtually all possible combinations of governing coalitions have been tried (Chiva, 2015).

The Romanian media market is dominated by television, with a recent increase in internet use and a continuous decline in newspaper circulation. Unsurprisingly, given the low labour force activation, high levels of poverty and low levels of education, the Romanian media market has recorded above-average rates of TV viewing and low levels of newspaper consumption, with a readership of just 13% of the population (BRAT, 2015). Highly reliant on advertising and receiving limited revenue from subscriptions and sales, the economic crisis brought a big slump in revenues for newspapers. The rapid development of the internet and the availability of free online content makes the survival of legacy organizations even more difficult in a country without a habit of reading and paying for news. The highest selling Romanian non-tabloid newspaper (a sports newspaper, Gazeta Sporturilor) sells fewer copies than the recently-closed high-brow paper in Hungary (Népszabadság), and Hungary has a population less than half the size of Romania’s. The print market in Romania is only 5% of the entire media market, compared with 28% in Hungary or 21% in the Czech Republic (Media Fact Book, 2016). The television market is dominated by the commercial channel PRO TV (Rating 4.3%, Market Share 19.3%), followed by Antena 1 (Rtg. 3.2%, Shr. 14.5%), Kanal D (Rtg. 1.6%, Shr. 7.2%) and news channel Antena 3 (Rtg. 0.8%, Shr. 3.8%). The public service broadcaster, TVR, has a very low share (Rtg. 0.4%, Shr. 1.98% for TVR1, according to Media Fact Book 2016) and high state debt of almost 700 million lei (150 million euro).

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Considering the national context outlined above, this assessment of media pluralism in Romania finds the highest risks to be in the areas of Market Plurality and Political Independence, more specifically with regard to the indicators on Independence of PSM governance and funding, Political control over media outlets and Editorial autonomy, followed by high risks for Commercial & owner influence over editorial content and Media ownership concentration.

3.1. Basic Protection (34% – medium risk)

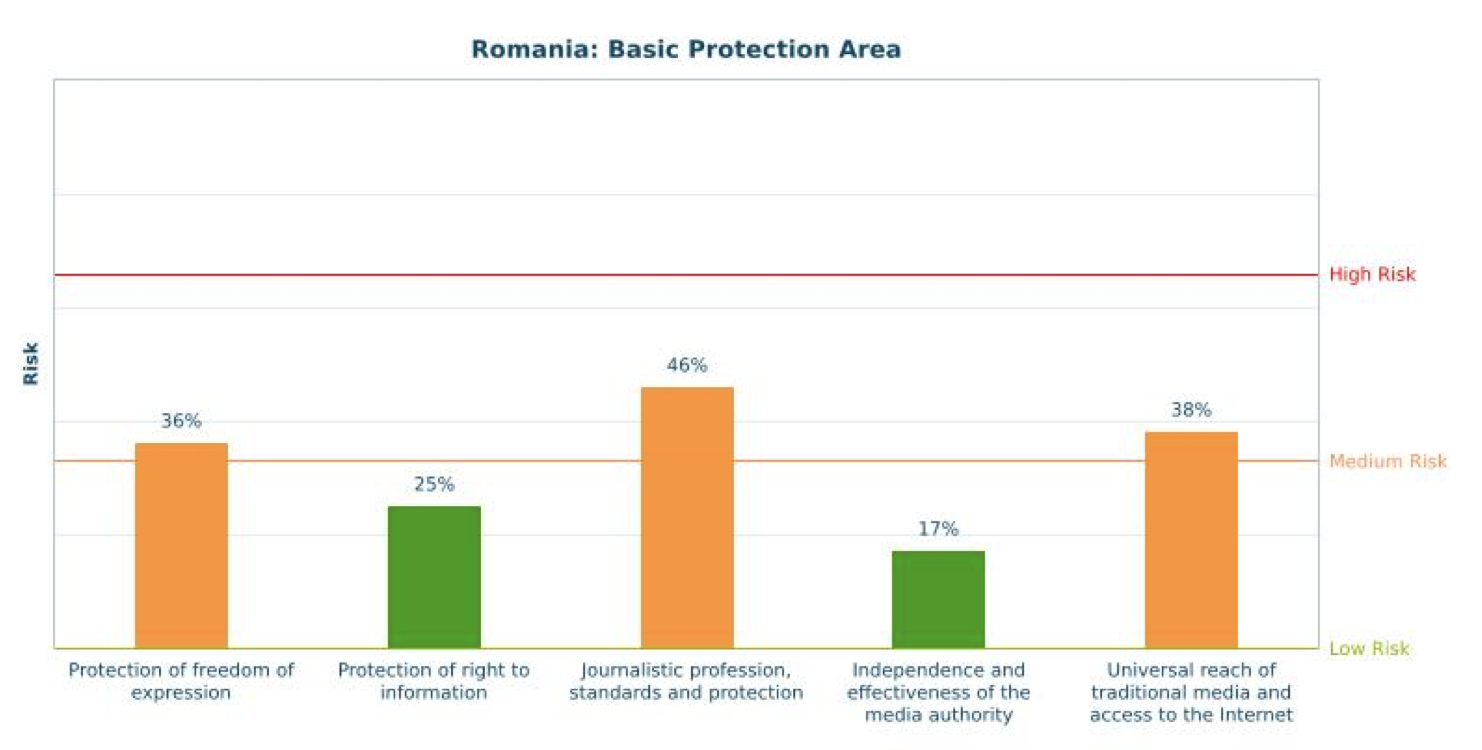

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure several potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that are responsible for regulating the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

Romanian legal provisions on issues of basic protection for the media sector provide a relatively solid framework. It is the inconsistent practices and implementation of these provisions that give rise to the potential risks in this area. This is, to a large extent, due to structural problems with the Romanian state institutions (justice system, administrative capacity) and to the socio-economic context. Issues related to the journalistic profession, standards and protection indicator, evaluated as medium risk (46%), represent the highest risk under the umbrella of “Basic protection.”[2]

The indicator on Protection of freedom of expression scores a medium risk (36%). Freedom of expression is recognized in the Romanian Constitution and in the Civil Code, and Romania ratified both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR). Restrictions of freedom of expression are clearly defined in the law, pursuing legitimate aims according to the ECHR. Defamation is decriminalized, but limitations to freedom of expression are stipulated in the Civil Code, protecting a person’s right to dignity, honour, privacy, personality and the right to their own image.

The right to information is recognized in the Romanian Constitution, as well as in Law 544/2001 on Free Access to Public Information. However, lengthy trials and inconsistent judicial practices reduce the effectiveness of appeal mechanisms regarding denial of access to information. Even though the Ministry for Public Consultation and Civic Dialogue introduced a mandatory, standardised list of public data that must be displayed on institutional websites, the measures taken to improve the response of public authorities to information requests are insufficient without proper judicial response to violations of the legal provisions. Therefore, the indicator on the Protection of the right to information records a low risk, but reaches quite a high percentage, 25%.

Similarly, the legislation regarding the media regulatory authority (National Audiovisual Council – CNA) provides adequate provisions in terms of appointment procedures and competencies. Nevertheless, although the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority is at a low risk level (23%), the authority is not truly effective in its mission. This is partly because its interaction with a slow judiciary leads to delayed implementation of decisions and partly due to the lack of professionalism of council members, who act as enforcers of narrow party – and occasionally private – interests, rather than as guarantors of the law.[3] The current president of the CNA is under investigation for corruption and abuse of power, but as there are no provisions for the council to dismiss her, there is a danger that a short term legal change aimed at removing her may jeopardise institutional independence in the long run.[4][5]

There are significant challenges to the protection of the journalistic profession, which, at a medium risk (45%), poses a serious threat to media pluralism. The protection of sources is legally guaranteed and not contested by political elites through formal means; nor have there been recent cases of violations. Still, there are reports of journalists being pressured to disclose sources, as well as threats to the digital and physical safety of journalists (CJI 2016, FreeEx 2016, IREX 2015, Tolontan 2014, 2016). Although access to the profession is not legally restricted, the situation of the market and the lack of safeguards of editorial independence and professional norms (see 3.5 and 3.4 below) can be considered possible entry barriers to the profession (Örnebring 2013). Retention is another issue, as there are severe limits to the practice of journalism (Bajomi-Lazar 2012, Stetka 2013, Obae 2015). The professional status, independence and integrity of journalists are threatened both directly, through interference with editorial content, pressure and intimidation exerted by employers, political figures and public authorities, and indirectly, through precarious contracts and delays in receiving salaries (CJI Report 2016, EMSS 2013).

Support from professional and labour organizations is limited; few if any actions are conducted to actively represent and legally support journalists (especially outside the public sector media – PSM). There is no binding self-regulatory Code of Press Ethics that would have enforcement or sanctioning power (see 3.2 below).[6][7] There are several journalists’ associations, but none of them is representative of the whole profession and the majority of journalists do not actively or even formally belong to a membership-based professional association (Romania country report MDCEE, Örnebring 2013). Most advocacy in support of journalistic professional protection comes from NGOs with a reputable and forceful activity but largely lacking strong grassroots membership or support in the major media organizations. This pattern is related to the low levels of trust and civic mobilization in Romania, which, naturally, affects all spheres of society (Zmerli & Van der Meer 2017); it is enhanced by journalists’ particularly precarious situation, as they face high job pressures and demands with no employment stability, as already mentioned.

The dismal situation in terms of journalistic standards and the protection of journalists, together with its structural (economic and regulatory) roots especially, increases the likelihood of negative ramifications in other related areas, such as risks of commercial and owner interference (2.4) and political control (3.3).

There is also a medium risk in terms of the universal reach of traditional media and access to the internet (38%). Although access to PSM is guaranteed by law, the percentages of the population covered by signal of all public TV channels (97%) and radio stations (98%), although much higher than in the 1990s, are still lower than those achieved by over two thirds of EU member states. Thus, in this assessment, they pose a high and medium risk, respectively, whilst digitalisation was delayed as 10% of households were at risk of having no access to digital transmissions.[8]

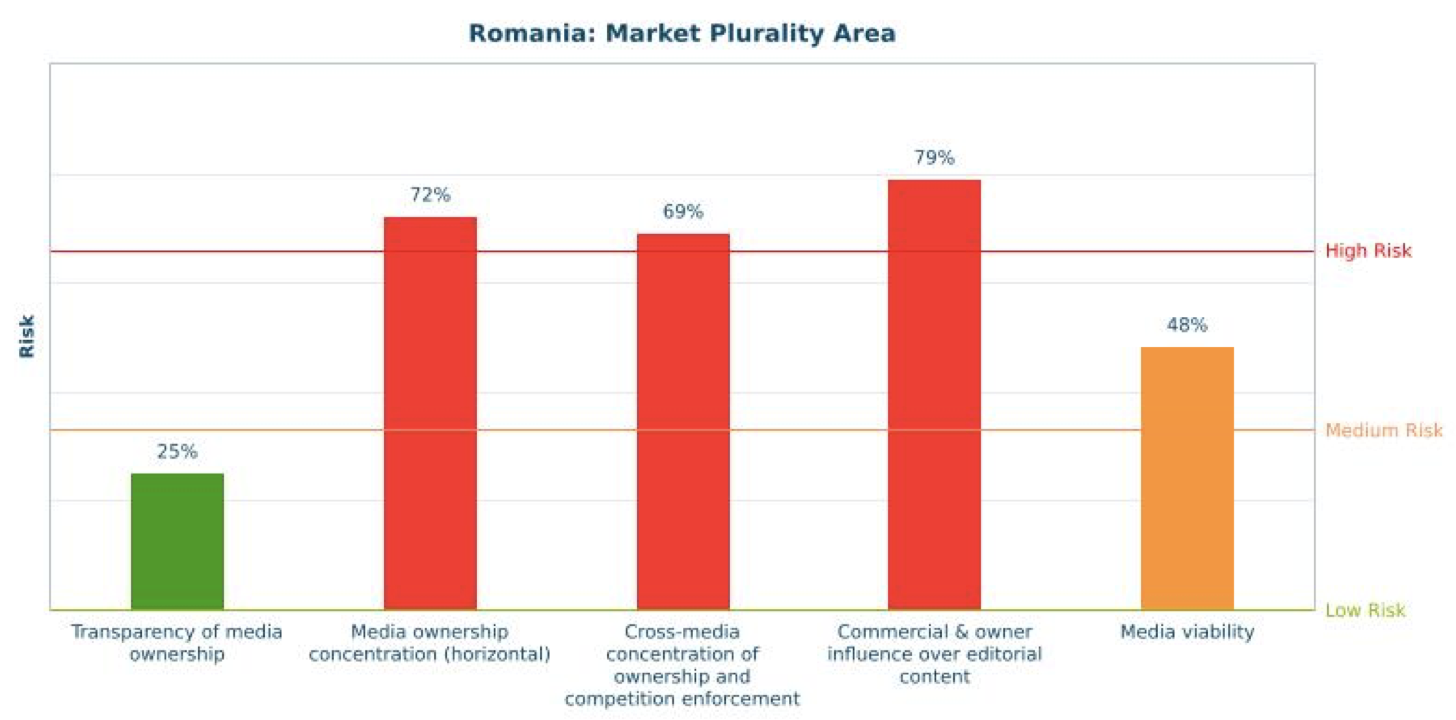

3.2. Market Plurality (64% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions regarding media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

A series of legal blind spots in media ownership regulation lead to considerably high risks to market plurality. Although media ownership information is made available by public authorities it is still possible to hide individuals’ names behind a long chain of companies, possibly not registered in Romania, meaning that transparency of media ownership is at medium risk (50%). There are high risks stemming from the lack of appropriate sector-specific legislation of concentration of media ownership (72%) and especially cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement (69%). Commercial and owner influence over editorial content poses an even higher risk (79%), partly due to the ineffectiveness of non-binding self-regulatory rules in a context of economic vulnerability of the media sector, which also contributes to a medium risk assessment of the media viability indicators (48%).

Even though media ownership information held by public authorities can be accessed by the public, the legal set-up hampers full transparency regarding the de facto media owners. The Audio-visual Law imposes a special regime for joint-stock companies holding audio-visual licenses, obliging them to hold only registered shares; however, companies publishing written press, in print or online, only need to abide by the legislation on general commercial companies, which allows joint-stock companies to hold both registered and bearer shares. This allows owners in the written press to hold shares without their identity being disclosed to public authorities, making it difficult to trace how much control or ownership certain legal or natural persons effectively have on the media market.

While the audio-visual legislation contains thresholds meant to prevent a high degree of horizontal concentration of ownership of broadcasters, there is no media-specific regulation for print and online media ownership and no cross-media ownership legislation.[9] These are subject only to the more general Competition Law, which regulates dominant positions on the market only from an economic perspective, and not from the perspective of the influence media may have on public opinion. The legal provisions and the remedies provided are insufficient to ensure a balanced concentration of shareholdings on the media market.

The financial reporting system for companies in Romania does not require a separation of revenues per sector of activity, making it impossible to establish a reliable market share for media companies. A wide range of services can be provided by a single media company owning radio or television channels, newspapers or Internet content, to which communication systems and infrastructure can be added, as is the case of Orange, Telekom, RCS&RDS or UPC. This poses significant problems in identifying dominant positions and high ownership concentration in the media market.

Moreover, data unavailability for sector-specific revenues affects the accurate assessment of media viability. Newspapers, in particular, are marred by insolvency cases and high debt; a modest growth in digital revenues and the few new scarce and underdeveloped alternative sources of revenue cannot compensate for the losses in print advertisement revenue (Center for Independent Journalism 2016; Activewatch 2016).

The audience concentration in the audiovisual media sector is 56%, comprising the audience share of the top four audiovisual media owners: Intact Media Group, ProTV SRL/CME Media Enterprises, Dogan Media International SA and Ridzone Computers SRL. Similarly, the audience concentration in the radio market is 57%, made up of the audience shares of top four radio owners: Societatea Română de Radiodifuziune, A. G. Radio Holding, Grupul Media Camina-Intact Media Group and Lagardere Active International. The audience concentration for the top four publishers of the newspaper sector is 88% (Adevărul Holding, Ringier Romania, Intact Media Group and the Romanian Patriarchy) and for the Internet content providers market 69% (Ringier Romania, Adevărul Holding, ProTV SRL and Realitatea Media SA).

Commercial and owner influence over editorial content is made possible by the precarious economic situation and the lack of safeguards for editorial independence previously mentioned. There are no binding self-regulatory mechanisms and no supervisory authorities that could prohibit or penalise commercial interference with decisions on editorial content or editor-in-chief appointments. The 1990s practice whereby journalists were tasked with procuring advertisement and sponsorship is now banned, and there are clear legal incompatibilities set in this respect. Advertisements and all advertorials are expected to be clearly marked, and several breaches have been penalised. However, media organizations or journalists are not accountable to anybody if they fail to respect the principles of editorial independence stated in the ethical codes, since there is no clear enforcement mechanism and none of the codes are binding in any way. In practice, this makes room for systematic compromises in terms of sponsorship and advertising, self-censorship, and biased editorial decision-making in favour of owners’ interests.

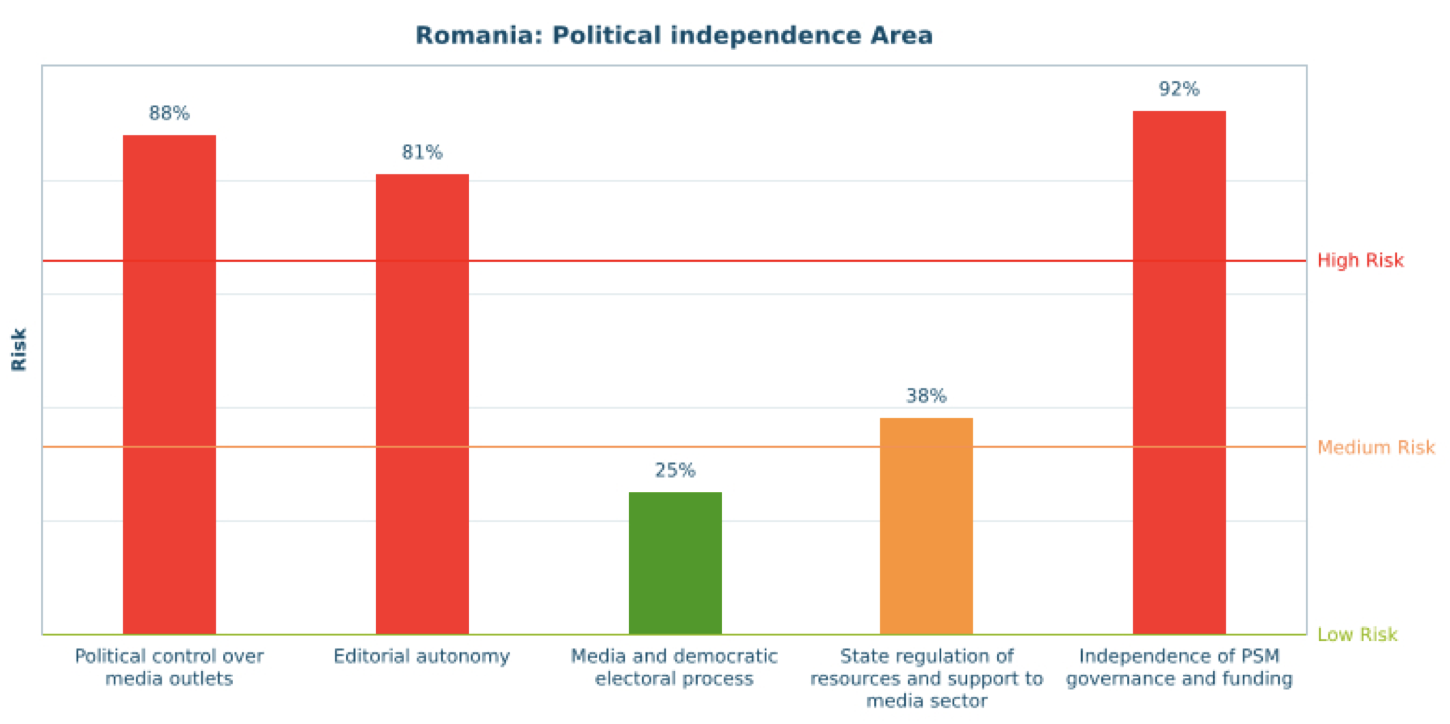

3.3. Political Independence (65% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Lack of political independence represents the most significant threat to media pluralism in Romania. It stems from both the regulatory framework and actual practice, made possible by structural factors such as dysfunction of the media market, high political polarization and weak impartial state institutions. Three indicators have a risk level over 80%: Political control over media outlets (88%), Editorial autonomy (81%) and the Independence of PSM governance and funding (92%). This is the domain with both the highest values, i.e. the biggest risks, among all indicators and the highest concentration of indicators at high risk. Although there is a low risk assessment with respect to Media and democratic electoral processes (25%) and a medium level in terms of the State regulation of resources and support for the media sector (38%), the three high risk dimensions identified have the potential to negatively influence the other two, even if, at the moment, a major spill-over effect is not detected in this assessment, given the specific measurements used in this study.

The risks of political control are evaluated as high (88%) with the current measurement because parties, partisan groups or politicians can be owners of all types of mass media (audiovisual, radio, newspapers, online). There are no specific rules on conflict of interest or incompatibility between political activities and media ownership. This legal situation represents a risk in itself, by opening the door to the direct involvement of political actors in the media. The practice of owning media channels is especially appealing in the context of a dysfunctional media market, where few (if any) media enterprises/outlets are profitable, but may prove valuable for other goals, for instance serving as tools in political and economic competition. The most recent such case is that of the news television channel România TV, which is owned by Sebastian Ghiţă, a former deputy and member of the Parliamentary committee for the oversight of the secret services. Ghiţă is a wealthy businessman, whose companies had a range of controversial contracts with state authorities and, allegedly, links with the secret services. He is currently under investigation for corruption. In the 2016 parliamentary election campaign, he used his TV channel to blatantly support his nationalist party, a splinter from the PSD (Social Democratic Party), and to launch denigrating attacks on the party’s opponents. He also uses the channel for personal vendettas, while being on the run from law enforcement (ActiveWatch, 2016; News.ro, 2016).

The possibility of political control of the media is increased by the fact that politicians are allowed to own media directly or indirectly (through family members) and actually do so. It is, however, the lack of safeguards for editorial autonomy, as previously mentioned, that changes the negative outcome from mere political bias (be it lacking in factual accuracy) to political control though owner interference into editorial content.[10] There are multiple reports of journalists being pressurized and threatened over their choice of topics and angle, about dismissals of journalists and editors for stepping out of line, as well as the use of media companies as bargaining chips in political deals (Martin and Ulmanu, 2016; CJI 2016; ActiveWatch, 2016).

Lower risks are registered with respect to Media and democratic electoral processes (25%), an indicator that reflects primarily the regulation of media access and coverage of electoral campaigns. This area, following intense scrutiny, is subject to stronger and clearer provisions regarding implementation and institutional responsibilities too (Popescu and Soare, 2014).

The State regulation of resources and support for the media sector presents a medium risk (38%). Both the legislative framework on spectrum allocation and its implementation are effective and there are no direct or indirect state subsidies for the private media sector. In the current measurement, the risk comes from state advertisement because, in spite of legal requirements of transparency, in practice it is virtually impossible to gather information at a sufficiently disaggregated level to check either the importance of state advertising for the budget of media outlets or the proportionality of the distribution of state advertisement to the audience share or audience profile (Popescu, Marincea, Gubernat, Lupea & Bodea, 2015, Center for Independent Journalism, 2015). The lack of discretionary allocation of subsidies in fact reflects the lack of any subsidies for independent public affairs media. Such a policy choice cannot be a priori viewed as a risk to media pluralism since it can reflect an ideological position or a view of the role of the state. It can however be considered as a risk if it reflects a withdrawal of the state as an impartial institution meant to support freedom of expression and access to information. This is a plausible interpretation in the Romanian case (see Introduction), given also the lack of universal access to mass media, which is corroborated by the dismal record of enabling an independent PSM, which registers the highest risk rating in the entire assessment (92%).[11]

Like in most post-communist countries, PSM in Romania struggle with issues of political independence. In the Romanian case, specific legislative provisions regarding dismissals and parliamentary oversight are unsuitable to promote independence. The executive board and its chairman, who also acts as general director, have a five-year term, but their dismissal can be triggered by the rejection of the annual report by Parliament without any performance evaluation. The lack of targets at the outset of a director’s term and of a solid assessment of the annual reports based on performance evaluation criteria driven by the institution’s public mission make the acceptance or rejection of the annual report dependent exclusively on (momentary) political support (OpenPolitics.ro, 2016; Popescu and Bodea, 2016). The licence fee had also not been an effective safeguard of either financial independence or financial security for the PSM because it was unilaterally set by the government and had not been increased since 2004. This vicious circle of institutional weakness and dysfunctional oversight contributed to a declining audience and increasing debt for Romanian public television (OpenPolitics.ro, 2016). In this context, and justified as a means to ensure appropriate levels of financing for the PSM, legislation passed at the end of 2016 replaced the licence fee with direct government funding starting from 2017. While interpretations of the change from licence fee to direct government funding are divided largely along partisan lines, it is difficult to say to what extent it can be considered as a crucial negative factor and yet another nail in the coffin of PSM, given the shortcomings of the status-quo ante. It is, however, possible to say that increasing PSM’s independence and commitment to public interest requires improvements to the current legislation around its main weak points (dismissals and oversight) as well as the enactment of a clear and transparent mechanism of government allocation of PSM funding, including a legally guaranteed role for the PSM to present its needs in line with objectives.

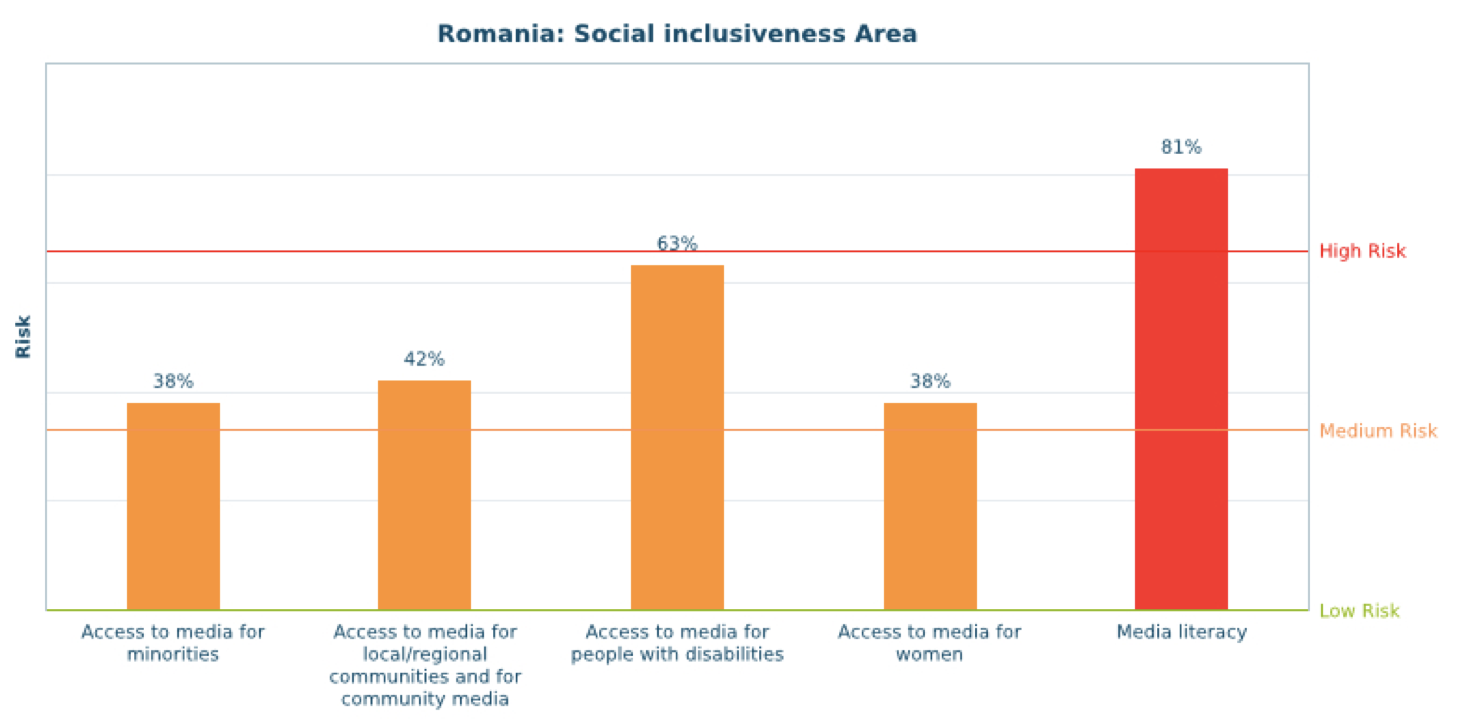

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (54% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Social inclusiveness indicators have generally been assessed at medium risk. The indicator Access to media for minorities scores a medium risk (38%). Related policies and legal provisions on access for ethnic minority groups are generally in place and are relatively well developed. However, the variables of this indicator do not fully capture inherent risk due to societal characteristics, such as the social acceptability of prejudice and thus problems of representation and recognition of minorities. Access to media for women poses the same level of risk (38%). Gender imbalances are manifest both in the overall news coverage, and in PSM management positions, women being still under-represented and only taking the lead in news reporting. Slightly higher risks appear in terms of access to media for people with disabilities (indicator score: 63%), where the current legislation is still lacking and the implementation of existing provisions such as using sign language translation and synchronous subtitles poses technical and financial difficulties for broadcasters. The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores a medium risk (42%), mostly because community media are not adequately defined and regulated. The media literacy indicator scores a high risk (81%). Media literacy faces structural challenges due in part to a lack of coherent policies[12], and in part to limited access to the Internet and digital skills.

There is a generally good PSM policy on access to airtime for minority groups and a relative inclusion of these groups in public radio and television programs, albeit disproportional in a few cases to the actual size of specific minority groups, with marginal groups like the Roma being underrepresented. A more proportional representation of minorities in Romania in the media sector does not depend just on PSM policy and practice, but also on the mobilization of minority groups and on journalists belonging to these groups, as expert Marius Cosmeanu pointed out[13]. Minority groups face problems regarding their portrayal, awareness of their rights (including the right to ask for airtime on PSM) and cohesion, which continuously reinforce existing inequalities. One of the visible consequences in the media sphere is better access and disproportionate airtime or higher number of publications for the more mobilized groups and less for the more marginalized ones (e.g. the Roma). Like parliamentary representation of minorities (Birch et al. 2003), programmes on PSM for ethnic minorities may be just a tokenistic mechanism, unless there is a more diverse representation of these groups in the media, which goes beyond stereotypical depictions. Such change in the coverage of minorities and their access to mainstream programmes is especially necessary given the widespread levels of prejudice and stereotypes in Romanian society (European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance 2014, TNS & National Council on Combatting Discrimination 2015, Chilin and Lup 2016).

Access to media for local/regional communities is granted through specific must-carry provisions. While it is legally possible for non-profits to own media licenses and products, the lack of consistency in defining community media in Romania leads to a mixed list of media platforms that address specific communities, produced either by non-profit entities or by public institutions or private enterprises. Although some existing radio and television channels would qualify as community media (e.g. Speranţa TV, TV Sigma, Radio Shalom and others), there is no community radio or television channel registered as such with the National Audio-visual Council, according to expert Dorina Rusu.[14] The lack of an explicit recognition of community media, in contrast with commercial and public media, leads to inherent economic limitations and instability, which in turn makes them vulnerable to becoming mouthpieces for the political interests of their sponsors.

Increasing the access of people with hearing impairments to mass-media was the goal of recent provisions in the Audio-visual Law requiring all national broadcasters to provide at least a 30-minute sign language version of their daily news programs (Art. 42, Law 103/2014). As this brings about specific expenses for media companies, reports signal the need for state support in technically implementing the policy nationwide.[15] The Audio-visual Law does not yet require support services for people who are blind or partially sighted, and thus a better policy regarding access to visual media content is needed.

Access to media for women is still disproportionate. The PSM does not have any gender equality policy. There were no reported cases of denial of equal rights in employment for women in the media sector between 2014 and 2016, yet there is a clear discrepancy[16], highlighted by the high percentage of women in lower-level positions (70% women, only 30% men) and the predominance of men in senior media management (Ross & Padovani 2017). Women are also under-represented in the news coverage of both traditional and online media. Only 35% TV news items are about women, radio or in newspapers, and the online has not done much to improve women’s media presence either (38% women compared to 62% men).[17] On the other hand, when it comes to news reporters the situation is more balanced in terms of gender, women reporters being slightly more common than men (57%).[18]

Low levels of socio-economic development and high inequality leave a significant part of the population without digital skills. Naturally, there is a dominant focus in the current education curriculum on ICT skills acquisition. Pre- and post-communist legacies in education contribute to an inefficient development of analytical skills, as revealed also by the latest PISA scores in reading and comprehension (OECD 2015). Although critical thinking has been included in the pre-university education program, the fact that over the last 10 years PISA results have remained very weak, with 40% of pupils unable to understand what they read, shows the failure of the educational system to develop basic skills like logic, argumentation and critical thinking, the skills that underlie media literacy. Most efforts to expand media literacy training come from NGOs, but regardless of their quality, they cannot be sufficient due to their inherently unsystematic character, given that none of them can fully assess levels of individual competences (communicative abilities, critical understanding of media content and use of specific skills).[19] Moreover, deeper structural issues related to socio-economic development and inequalities put media literacy in a wider context of access to IT infrastructure and even to basic education, as Romania has both some of the lowest PISA scores and the highest rates of school dropout (OECD 2015 and Eurostat 2015). Therefore, a real assessment, as well as any plan to improve media literacy, represents rather challenging issues that are tied primarily to the more general socio-economic development of Romania.

4. Conclusions

Although, like democracy, media pluralism is always a work in progress, risks in some countries are higher than in others and medium or even low risks may interact and, in conjunction, threaten the democratic performance of the media system. This is the case in Romania, where the media fall short in their duty to inform the public either as citizens or consumers, by frequently acting as agents of often intertwined commercial and political interests and in breach of journalistic norms of accuracy, balance or completeness.

In an economically difficult context, issues of recruitment and retention and precarious employment pose problems for the journalistic profession, which are further enhanced by the lack of institutionalized safeguards of editorial independence either for chief-editors or for rank-and-file journalists. Existing ethical codes are not binding and there are no enforcement mechanisms, self-regulatory or otherwise, whilst most journalists outside of the PSM are not part of active professional or labour organizations, which are generally weak in Romania.

In turn, owners not bound by any formal requirements to respect editorial independence are also not bound by specific media conflict of interest rules or cross-media ownership limits. This further encourages the existing tendency to own media for ulterior motives such as political and economic leverage.

Multiple confounding structural factors – social, economic and political – including a dysfunctional media market, weak state capacity and a symbolically polarized political competition, contribute to the situation of the media in Romania. This assessment identifies specific deficiencies in the legal or regulatory framework that represent risks even though they are not in themselves the only (or possibly not even the main) causes of the dysfunctions. Fixing these legal and regulatory shortcomings might not bring an (immediate) improvement in the quality of the information environment. Yet to have any chance of better media performance requires the elimination or at least limiting of such specific risks once they have been clearly identified and understood. In other words, they are necessary but not sufficient conditions for a major change in media pluralism in Romania.

References

ActiveWatch. Raportul Freeex: Libertatea Presei în România 2015-2016. <https://www.activewatch.ro/Assets/Upload/files/FreeEx/rapoarte/Raport%20FreeEx%202015-2016.pdf>.

ActiveWatch, Center for Independent Journalism and Convention of Media Organizations. Inițiativă transpartinică periculoasă pentru independența CNA. 3 July 2015. <https://www.cji.ro/initiativa-transpartinica-periculoasa-pentru-independenta-cna-2/ >.

ActiveWatch. Consiliul Național al Audiovizualului, martor pasiv al intoxicărilor și manipulărilor de la România TV. 8 December 2016. <https://activewatch.ro/ro/freeex/reactie-rapida/consiliul-national-al-audiovizualului-martor-pasiv-al-intoxicarilor-si-manipularilor-de-la-romania-tv/ >.

Adrian Vasilache. “Aproape 500.000 de gospodarii din Romania risca sa ramana fara servicii TV de la 17 iunie 2015/TVR si SNR cer Guvernului sa prelungeasca transmisia analogica pana la sfarsitul anului 2016”. HotNews.ro. 6 March 2015. <https://economie.hotnews.ro/stiri-telecom-19565057-aproape-500-000-gospodarii-din-romania-risca-ramana-fara-servicii-17-iunie-2015-tvr-snr-cer-guvernului-prelungeasca-transmisia-analogica-pana-sfarsitul-anului-2016.htm>.

Alton Grizzle and Maria Carme Torras Calvo (eds.). Media and Information Literacy: Policy and Strategy Guidelines. UNESCO, 2013.

Cătălin Tolontan. “În apărarea surselor și în atenția lui Victor Ponta.” Tolo.ro, 29 October 2014.

<https://www.tolo.ro/2014/10/29/in-apararea-surselor-si-in-atentia-lui-victor-ponta/>.

Center for Independent Journalism (CJI). Mass-Media in Romania in 2014-2015. 2016. <https://www.cji.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Mass-media-English1.pdf>.

Center for Independent Journalism (CJI). Monitoring the Spending of Publicity Budgets of the EU-funded Projects. 2014.

Center for Media Pluralism and Freedom (CMPF). Status of European Journalists. <https://journalism.cmpf.eui.eu/maps/journalists-status/>.

Cristina Chiva. “Strong Investiture Rules and Minority Governments in Romania”, in Rasch, B.E., Martin, S. and Cheibub, J.A. eds., Parliaments and Government Formation: Unpacking Investiture Rules. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. pp.198-216.

Chris Hanretty. Public Broadcasting and Political Interference. Abingdon/New York, Routledge, 2011.

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance. ECRI Report on Romania (fourth monitoring cycle). Council of Europe, 3 June 2014.

European Union. Education and Training Monitor 2016: Romania. 2016. <https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/monitor2016-ro_en.pdf>.

Heller, W. B. and Mershon, C. (eds.) Political Parties and Legislative Party Switching, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Henrik Örnebring. Journalistic Autonomy and Professionalisation. University of Oxford and The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013.

<https://mde.politics.ox.ac.uk/images/Final_reports/ornebring_2013_final%20report_posted.pdf >.

Initiative. Media Fact Book Romania 2016. 2016.

Karen Ross and Claudia Padovani (eds.). Gender Equality and the Media: A Challenge for Europe. Routledge, 2017.

Klein, E., 2016. “Electoral Rules and Party Switching: How Legislators Prioritize Their Goals”. Legislative Studies Quarterly, First View, DOI: 10.1111/lsq.12128.

IREX. European & Eurasia Media Sustainability Index 2015: Romania. Washington, DC: IREX, 2015.

Manuela Preoteasa, Iulian Comănescu, Ioana Avădani, Adrian Vasilache. Mapping Digital Media: Romania. A report by the Open Society Foundations. Open Society Foundations, 2010. <https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/mapping-digital-media-romania-20130605.pdf>.

Marina Popescu, Roxana Bodea. “Taxa Radio-TV, o problemă secundară?”. OpenPolitics.ro. 11 November 2016. <https://www.openpolitics.ro/taxa-radio-tv-o-problema-secundara/>.

Marina Popescu, Adina Marincea, Ruxandra Gubernat, Ioana Lupea and Roxana Bodea. Media Pluralism in Romania: A Test Implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor. 2015. <https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/mpm2015/results/romania/>.

Marina Popescu, Tania Gosselin and Jose Santana Pereira. European Media Systems Survey 2013. Data set. Colchester, UK: Department of Government, University of Essex, 2013.

Marina Popescu and Sorina Soare. “Engineering party competition in a new democracy: Post-communist party regulation in Romania” in East European Politics, 30(3): 389-411, 2014.

Median Research Centre. Interview with Francisc Simon. 4 July 2016.

Median Research Centre. Interview with Marius Cosmeanu. 27 June 2016.

Median Research Centre. Interview with Nicoleta Fotiade. 4 July 2016.

Median Research Centre. Interview with Tudorina Mihai. 30 September 2016.

Mihail Chiru. Rethinking Constituency Service: Electoral Institutions, Candidate Campaigns and Personal Vote in Hungary and Romania. PhD Dissertation, Central European University Budapest, 2015.

National Institute of Statistics – INS. Rezultate definitive ale recensământului Populației și al Locuințelor – 2011. 2011. <https://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/REZULTATE-DEFINITIVE-RPL_2011.pdf>.

News.ro. Valentin Jucan, membru CNA, despre înregistrarea cu Ghiţă: Voi sesiza DNA în cazul RomâniaTV pentru favorizarea infractorului. 29 December 2016. <https://www.news.ro/cultura-media/valentin-jucan-membru-cna-despre-inregistrarea-cu-ghita-voi-sesiza-dna-in-cazul-romaniatv-pentru-favorizarea-infractorului-1922403729002016121516453725 >.

OECD. PISA 2015. Results in Focus. 2016. <https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015-results-in-focus.pdf>.

OpenPolitics.ro. De ce a ajuns TVR falit și irelevant?. 21 March 2016. <https://tvr.openpolitics.ro/de-ce-a-ajuns-tvr-falit-si-irelevant/>.

Péter Bajomi-Lázár. Romania. A country report for the ERC-funded project on Media and Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. 2011.

Petrişor Obae. “Cătălin Tolontan: La Dan Voiculescu ai foarte multă libertate, câtă vrei să îţi iei.” Pagina de Media, 19 June 2015. <https://www.paginademedia.ro/2009/04/interviurile-lui-obae-catalin-tolontan-la-dan-voiculescu-ai-foarte-multa-libertate-cata-vrei-sa-iti-iei>.

Petrişor Obae. “Filaj la Tolontan în noaptea dezvăluirilor despre ISU. Tolo: s-a întamplat la fel în Gala Bute.” Pagina de Media, 25 Nobember 2015.

Pop-Eleches, G. “A party for all seasons: Electoral adaptation of Romanian Communist successor parties”, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 41 (4): 465-479. 2008.

RADIOCOM. Aria de acoperire cu semnal DVB-T2 a fost extinsă la aproximativ 62% din populaţie. 3 June 2016. <https://www.radiocom.ro/stiri/Acoperire_62/>.

Radio România. Raportul de activitate al Societății Române de Radiodifuziune pe anul 2015. 2016 <https://www.srr.ro/files/CY1923/RAPOARTE/RadioRomania-RAPORTANUAL2015.pdf>.

Răzvan Martin and Alexandru Brăduț Ulmanu. De ce și cum se clatină TVR: Mărturii din interiorul televiziunii publice. FreeEx Series. ActiveWatch, 2016. <https://www.activewatch.ro/ro/freeex/reactie-rapida/de-ce-si-cum-se-clatina-tvr-marturii-din-interiorul-televiziunii-publice/>.

Romanian Transmedia Audit Bureau – BRAT. Consumul de media şi investiţiile în publicitate. 16 December 2015. <https://www.brat.ro/stiri/consumul-de-media-si-investitiile-in-publicitate.html>.

Sarah Macharia. “Who Makes the News?”. Global Media Monitoring Project 2015. <https://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/global/gmmp_global_report_en.pdf>.

Sergiu Gherghina, Mihail Chiru. “Taking the Short Route: Political Parties, Funding Regulations and State Resources in Romania”, East European Politics and Societies, 27(1): 108-128. 2013.

Sonja Zmerli and Tom W.G. van der Meer (eds.). Handbook on Political Trust. Elgar, 2017.

Tania Chilin and Oana Lup. (2016). ADID in Romania: A longitudinal approach. Available at: <https://lesshate.openpolitics.ro/dia-discursul-intolerant-si-anti-democratic-in-romania-o-abordare-longitudiala/>.

TNS and National Council for Combating Discrimination (CNCD). Percepții și atitudini ale populației României față de Strategia națională de prevenire și combatere a discriminării în vederea implementării proiectului predefinit ”Îmbunătățirea măsurilor antidiscriminare la nivel național prin participarea largă a profesioniștilor și societății civile”. 2015 <https://nediscriminare.ro/uploads_ro/166/Sondaj_TNS_CNCD_2015.pdf>.

Václav Štětka. Media Ownership and Commercial Pressures – Pillar 1 Final report. University of Oxford and The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013

<https://mde.politics.ox.ac.uk/images/Final_reports/stetka_2013_final%20report_posted.pdf>.

***. Global Media Monitoring Project 2015. National Report. Romania. 2015. <https://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/national/Romania.pdf>

***. Law 103/2014. Audiovisual Law, with modifications and additions to Law 504/2002. <https://www.cna.ro/IMG/pdf/LEGEA_AUDIOVIZUALULUI_CU_MODIFICARI_SI_COMPLETARI_DIN_2014.pdf>.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers who carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Marina | Popescu | Senior Researcher | Median Research Centre | X |

| Adina | Marincea | Researcher | Median Research Centre | |

| Adriana | Mihai | Researcher | Median Research Centre | |

| Roxana | Bodea | Researcher | Median Research Centre |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

Considering the standard Group of Experts procedure, which involved reviewing answers and evaluations of the Romanian Team by media experts, we mention that no representative of a broadcaster organisation was available for participating in the present study. The list of experts consulted is the following:

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Răzvan | Martin | NGO researcher | ActiveWatch |

| Ovidiu | Gherasim-Proca | Academic | University Al. I. Cuza, Iaşi |

| Manuela | Preoteasa | NGO/ Academic researcher | EurActiv |

| Ioana | Avădani | Representative of a journalist organisation | CJI |

| Alexandru Ion | Giboi | Representative of a publisher organisation | Agerpres |

| Dorina | Rusu | Representative of media regulator | National Audiovisual Council (CNA) |

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

Date: 27 April 2016

Place: European Commission Representation in Romania

List of participants (name, affiliation): Marina Popescu (MRC), Adina Marincea (MRC), Roxana Bodea (MRC), Cristian Buchiu (European Commission), Petrişor Obae (Pagina de Media).

The Media Pluralism Monitor 2015 for Romania was launched on 27 April 2016 in an event co-organised by the European Commission’s Representative in Romania and the Median Research Centre (MRC) at the Representative’s HQ in Bucharest.

Chaired by Cristian Buchiu, Vice-Head of the European Commission Representation in Romania and having as discussant the media journalist Petrişor Obae, the event was attended by 24 people including journalists, NGO representatives, scholars, as well as representatives of the embassies of Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Portugal and the USA.

There was a short presentation of the results of the MPM and their implications for Romania. The discussion focused on the risks for Romanian journalism, the dire situation of the public service media in Romania, the balance between ethical, moral and cultural determinants versus structural and legal issues. Several participants had questions about structural and legal matters and tried to understand better the mechanisms and the roots of the risk assessed. The discussant noted the stalled development of the media market and professional journalism in Romania, which was hit by the economic crisis at ‘adolescence’, thus never matured, which makes it difficult to self-regulate or to fight owner interference. Another participant emphasized the precarious nature of the journalistic profession at present and the lack of any institutional mechanisms to reverse the trend.

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report, “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Note that the format of the current measurement may obstruct the extent of the problem and should not be read as an improvement on the situation from the 2015 report.

[3] Council member Dorina Rusu confirms CNA’s poor effectiveness and internal problems, providing an example in which, although several broadcasters committed the same violation of the law in their coverage of the Colectiv tragedy in 2015, only one of them was penalised.

[4] Testimonies from CNA president Laura Georgescu’s trial also reveal potential abuse of power and interference in the legal decision-making process: https://www.paginademedia.ro/2017/01/procesul-laura-georgescu-martor-mi-a-spus-sa-trec-date-nereale-la-reclamatii-m-a-amenintat-ca-ma-muta-la-monitorizare-tintele-antena-3-nasul-tv-si-estrada

[5] See the open letter addressed to President Klaus Iohannis by NGOs ActiveWatch, Center for Independent Journalism and the Convention of Media Organizations on the risks posed by introducing a legal provision by which, through parliamentary rejection of the annual report of CNA, the president of the institution is also dismissed. This leaves room, according to the letter, for arbitrary and abusive dismissals.

[6] As Ioana Avădani mentioned, “the Group for Good Media Practices is not functional, and the Romanian Press Council [Club] is dormant (no public positions in years).”

[7] The codes were produced by the COM – Convention of Media Organizations, an umbrella organization comprising about 30 NGOs with programmes in the media sector, primarily led by ActiveWatch and the Center for Independent Journalism, and the CRP – Romanian Press Club, the first journalistic professional association, which represents more media outlets (24 members, publishers and broadcasters) than individual journalists (only 20 members). Individual organizations also have codes of conduct or ethics but, with the exception of the PSM, they do not have clear procedures for enforcing them and the codes can even be abused by the management.

[8] See Vasilache, 2015; RADIOCOM, 2016.

[9]Also see in Mapping Digital Media: Romania report https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/mapping-digital-media-romania-20130605.pdf; not regulating cross-media ownership can lead to problematic situations in which cable companies which are signal transmitters or telecom operators also become broadcasters and own audiovisual licenses. The same situation applies for advertising companies owning publications.

[10] The practice of control over content is difficult to measure (compared with just partisan bias) and there are variations in the extent to which bias is the result of pressure or journalistic choice. Even within the notorious media empire of the Voiculescu family, Gazeta Sporturilor and the public affairs blog of Cătălin Tolontan, its chief editor, have been critical of the activities of the owner, his family and his political organizations, including through investigative journalism. This is an independence that was explicitly agreed upon and supported by the media outlets’ profitability (according to the chief editor, see Obae, 2015).

[11] The downwards change from the previous year does not indicate a deterioration but is due to the simplification of the coding, with the elimination of the medium risk for some questions and the recommendation of negative ratings on appointments procedures in spite of being in line with what is usually evaluated as conducive to independence (Hanretty 2011). For an alternative analysis see https://tvr.openpolitics.ro/.

[12] Interview with Nicoleta Fotiade, 4 July 2016, by Adriana Mihai (Median Research Centre). Available upon request, in English.

[13] Interview with Marius Cosmeanu, Skype, 27 June 2016, by Adriana Mihai (Median Research Centre). Available upon request, in Romanian language.

[14] Opinions from the Experts consulted in the project – Dorina Rusu, 25 August 2016.

[15] It is worth mentioning that, like the problems encountered by ethnic minorities, people with disabilities also face significant representation issues in the media, as Francisc Simon, president of the National Organisation of People with Disabilities in Romania (ONPHR) Federation, pointed out: Interview with Francisc Simon, 4 July 2016, by Adriana Mihai (Median Research Centre). Available upon request, in Romanian language.

[16] Interview with Tudorina Mihai, 30 September 2016, by Adriana Mihai (Median Research Centre). Available upon request, in Romanian language..

[17] Global Media Monitoring Project 2015. National Report. Romania, p. 10.

[18] Macharia, 2015, p. 123.

[19] These are the criteria put forward by UNESCO and the European Commission.