Portugal

Download the report in .pdf

English – Portuguese

Authors: Francisco Rui Cádima (Coord.); Carla Baptista; Luís Oliveira Martins; Marisa Torres da Silva

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Portugal, the CMPF partnered with Francisco Rui Cádima, Carla Baptista, Luís Oliveira Martins and Marisa Torres da Silva (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa), who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

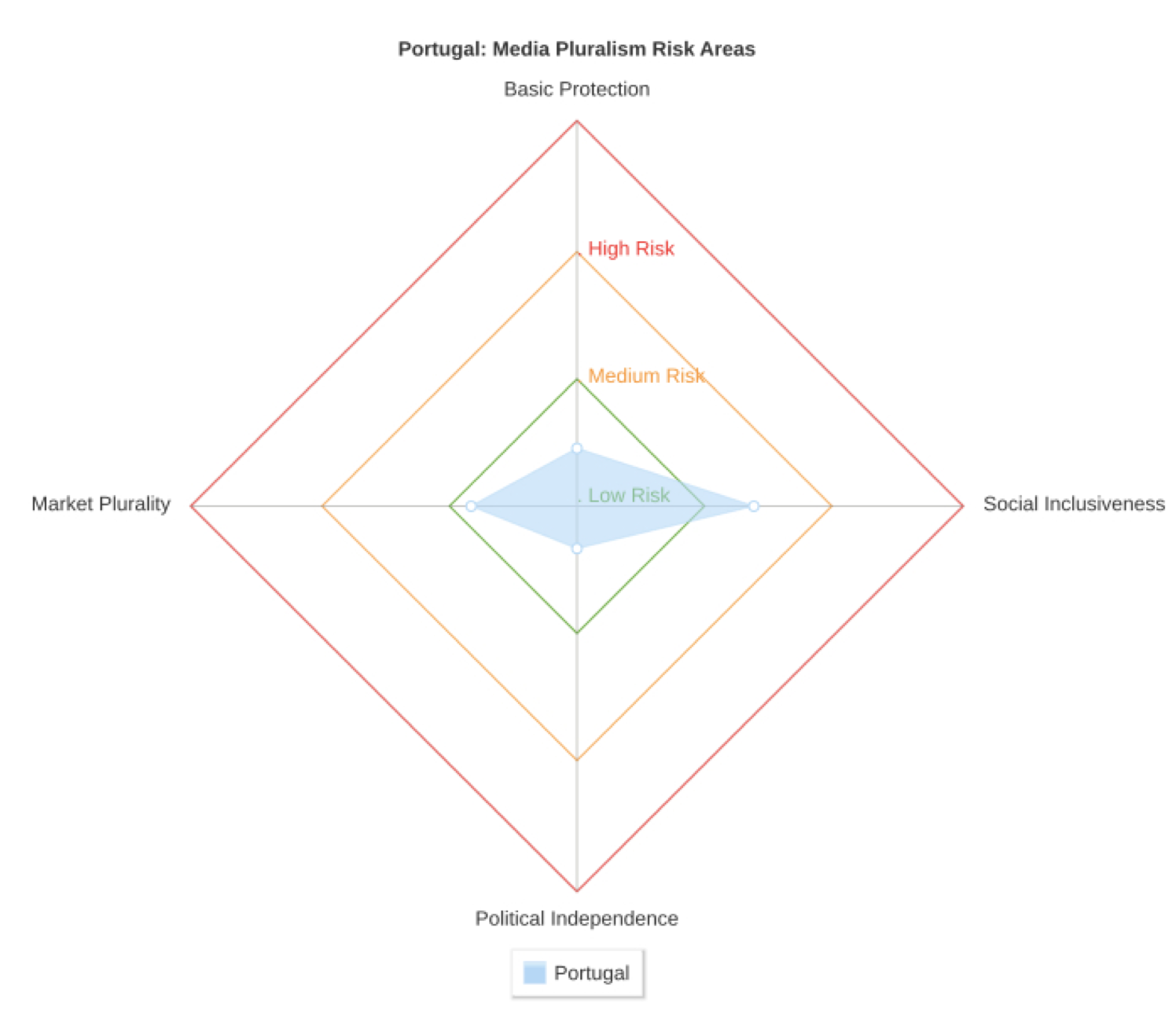

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Portugal was founded in 1143 by D. Afonso Henriques, after the Kingdom of Leon recognised him as King of the County of Portugal. Considered by some historians as the first global empire on earth, Portugal evolved into an important and powerful nation during the age of discoveries (XV to XVI centuries) establishing colonies all over the world. From then until now, Portugal has suffered successive economic crises, having had in the XX century a dictatorship of almost five decades (1926-74). Democracy was restored in 1974 after the April carnation revolution, and the first free elections took place in 1975. In 1986 the country joined the European Union (EU).

In a country with 10.38 million inhabitants, the current unemployment rate is 10.8%. It should be noted that in 2016, according to Eurostat, the youth unemployment rate was 28.6% (above the average rate in the EU, calculated as 18.6%). Real GDP growth rate was low in 2015 (1.6%), but the country managed to break out of the strong depression of the previous years. The preliminary data for 2016 indicates a high probability of moderate economic growth. However, public debt remains one of the highest in the EU.

The official language is Portuguese and there are no national minorities representing more than 1% of the population[2]. However, Portugal has its own ethnic minorities: Roma people, Africans from the former colonies and, in a more recent context, as a result of a strong influx of immigrants (particularly between 1998 and 2008), some international communities have become more visible and important in the national economic context: namely Brazilians, Ukrainians and Chinese.

With regard to the media, Portugal has always had one of the lowest newspaper reading rates in Europe. Only 26% of adults read newspapers on a daily basis. Television remains the most popular medium, but the majority of viewers access the main TV channels by cable. DTT (Digital Terrestrial Television) has a residual distribution system in the broadcasting context despite its coverage rate of 100% (terrestrial + satellite). DTT penetration rate in Portugal (TV sets), unlike what happened in other European countries, is only 23.4% in 2016. Since December 1, the number of DTT channels has increased to 7, with two new public channels being included: RTP Memory and RTP 3. However, Portugal remains one of the European countries with the lowest range of DTT channels on offer.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The Portuguese legal and constitutional framework and the mechanisms and practices of Portuguese media regulation are, somehow, the safeguard bases of the media system balance, which is mainly typified, as it turns out, between low and medium risk in most of the indicators.

There is still a set of concerns that bring us closer to potentially high-risk situations in various contexts, for example in terms of social inclusiveness, media ownership, and also with regard to the limited supply of DTT channels, to name some of the key issues. But we must be aware of the problem of the crisis and precariousness in journalism and in Portuguese media companies, whose first impacts endanger the safeguarding of professional independence. Although these cases are not easily measurable, the truth is that they cannot be forgotten, otherwise it will not be possible to prevent and /or mitigate their future impacts.

In terms of the results of data collection and media pluralism risk areas in Portugal, the biggest concern is related to media ownership exactly because the horizontal concentration already represents a high risk (67%), and therefore, also to the issue of transparency of ownership, the stability of the economic system of the media, and still the need to establish clear rules for cross-ownership. Overall, the Market Plurality area did not reveal other problems. The main exception is the indicator of Media ownership concentration that is at the borderline of high and moderate risk. This situation must be monitored in the future in a much more focused way by the regulator (ERC). However, we must say, the small population, the economic crisis and the low income levels of Portugal limit the number of competitive operators.

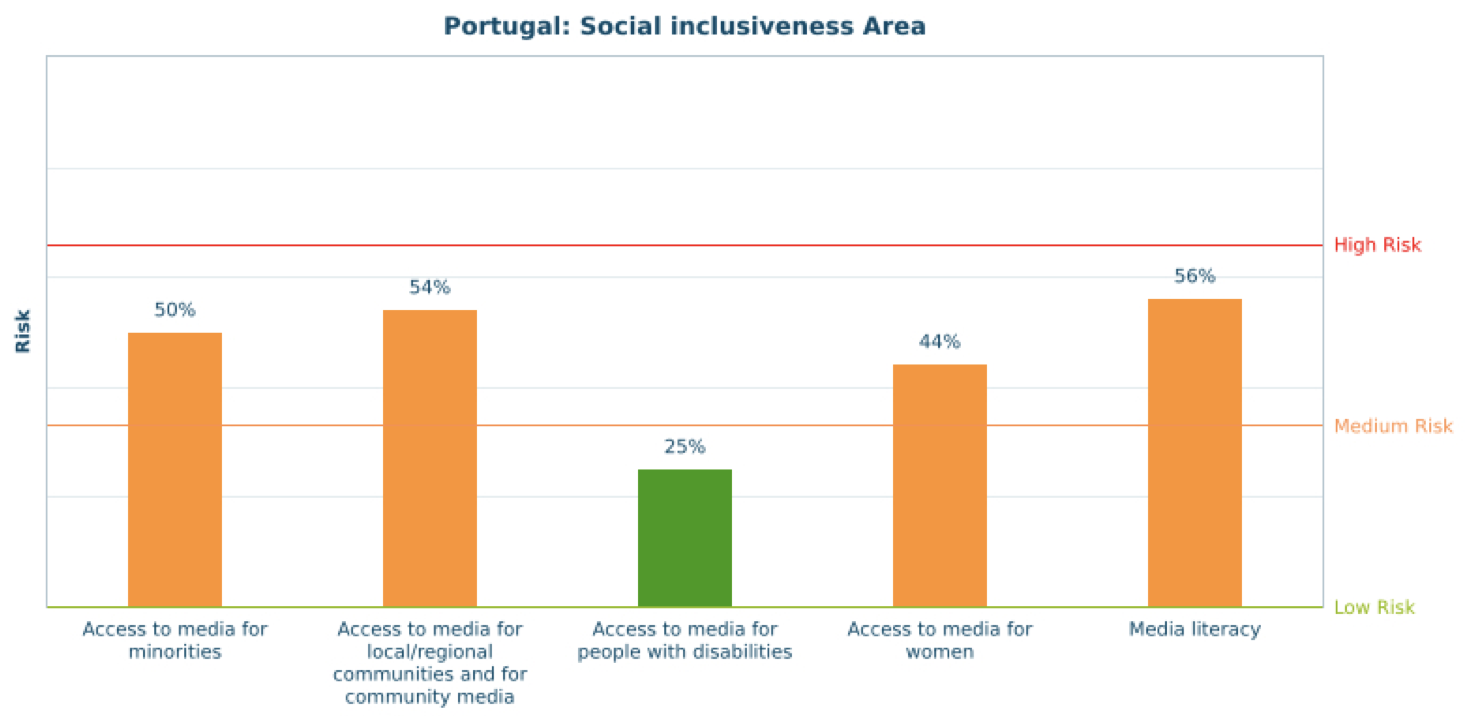

Special attention should be given by the regulatory authority (ERC) and civil society to the Social Inclusiveness area (46% – medium risk). Media and digital literacy (56% – medium risk) have an important and strategic dimension to improve the national scene, as well as the Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media (54% – medium risk). And also in terms of Access to media for women (44%) and Access to media for minorities (50%), both with medium risk. We have also identified a situation in which there has been a significant investment, especially by the public media, which has to do with the Access to media for people with disabilities (25% – low risk).

We should say that in the overall assessment of the risks to media pluralism in Portugal, the less critical situations are found in the specific areas of Basic Protection (15% – low risk), which concern, namely, the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information. In this domain, particular attention must be given to the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet (medium risk – 34%). The Political Independence area (11% – low risk), which assesses the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the Portuguese media system, is the best domain in this assessment.

In the public service media, that is to say, on the radio and especially on public television, there has been a progressive, albeit slow, adjustment of the television offers to the public service remit; but a stronger commitment of the concessionaire to some of the key issues in the context of the European 2020 goals is necessary, namely on diversity, pluralism and inclusion, both in terms of programmes and in terms of the company’s human resources.

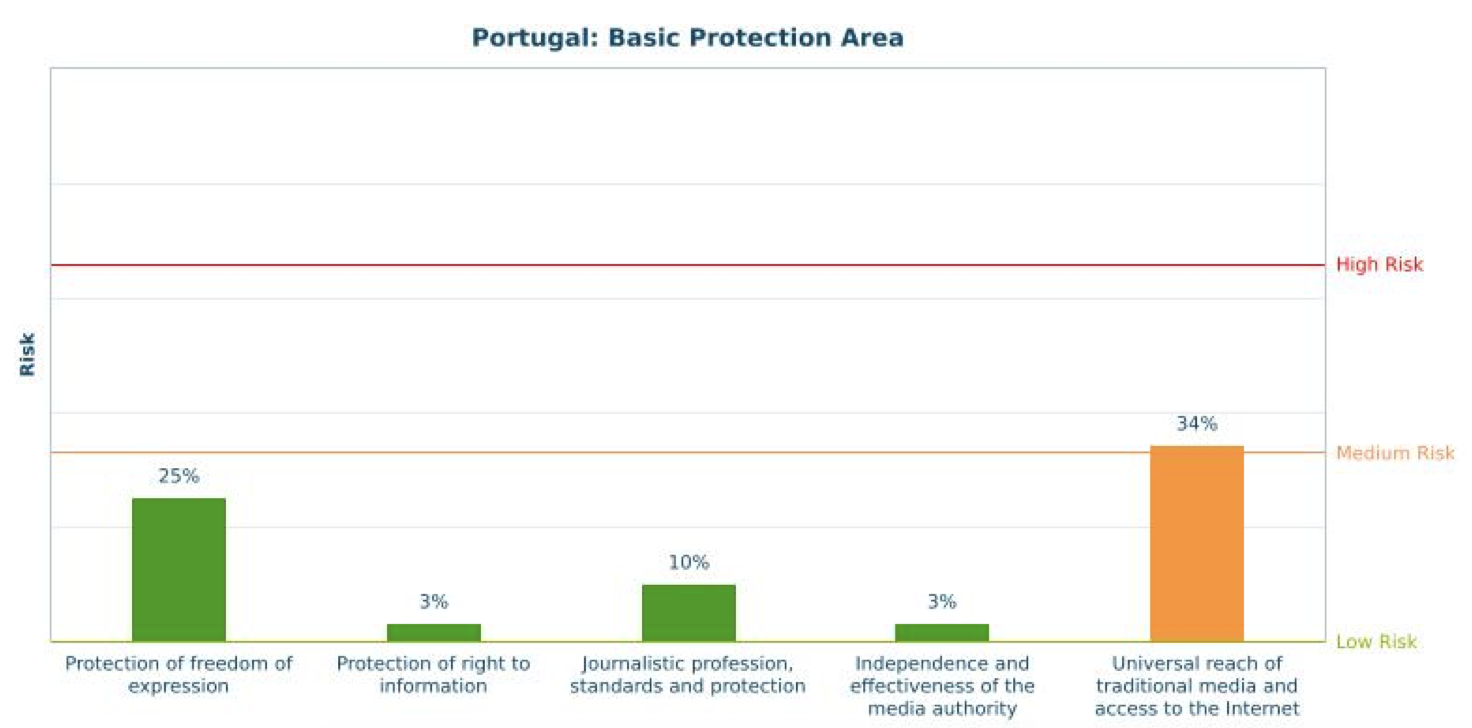

3.1. Basic Protection (15% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The indicator of Protection of freedom of expression scores low risk (25%). Freedom of expression is explicitly recognised in the Portuguese Constitution and the regulatory safeguards in this context are effectively implemented. Portugal ratified the main international treaties covering standards on freedom of expression and both Press law and the Constitution of the Republic apply to online and offline media in what concerns freedom of expression. The media regulator body (ERC) asserts that digital publications are also subject, with the necessary adaptations, to the Press Law.3

The restrictions to freedom of expression online are in general adequate to safeguard the constitutional aim pursued. We may say that there are no violations of freedom of expression online, either by the state or by the ISPs. The known cases are not arbitrary but exclusively concern the situations that are violating property rights. There is even in this matter a memorandum of understanding where the ISP’s are represented[3]

Concerning Protection of the right to information (low risk – 3%), there is an effective implementation of regulatory safeguards, namely through article nº 268 of the Constitution (Citizens’ rights and guarantees). The restrictions to freedom of information on privacy grounds are clearly defined in national law in accordance with international standards, namely through the principle of Open Administration and through the right of citizens to be informed (prescribed in the Press Law). Regarding the right of citizens to be informed by the media, the right to privacy, and/or restrictions to freedom of information, we consider that there is no significant risk of violation in Portugal.

The indicator of Journalistic profession, standards and protection scored low risk (10%). In general, media laws and self-regulatory instruments prescribing journalistic ethical values demand journalists act with transparency, objectivity, proportionality and non-discriminatory views. In practice, access to the journalistic profession is open. After a mandatory internship, there is a fee to pay to the CCPJ – Comissão da Carteira Profissional de Jornalista (Journalists’ Professional License Committee) – in order to obtain a professional licence, but it is not really a barrier to entering the profession.

However, there is still a lack of self-regulation in this profession in Portugal. It is important to reinforce the efficacy and proactivity of the Journalists Union’s Deontological Council (Sindicato dos Jornalistas – SJ). Portuguese journalists and their associations need to be more determined in terms of defending editorial independence. It is crucial also to rethink the models of self and co-regulation and to be more attentive about the working conditions of journalists, namely regarding job insecurity and precariousness. This is something on which the Union, the API (Portuguese Press Association), Journalists’ Professional License Committee, Media outlets and regulatory authority (ERC) should work seriously.

Concerning the safety of journalists and cases of attacks or threats, there are some reported episodes related to verbal violence (with a few involving also physical violence). There are also a few denunciations concerning the existence of threats to the digital safety of journalists, including through illegitimate surveillance of their searches and online activities, their email and social media profiles. We believe that in general, in Portugal, given the knowledge and specificity of past cases, it does not represent a dangerous situation for journalists.

With regard to the Independence and effectiveness of the media authority, there are no critical analyses or reports by any national or international organization, academic research or other reliable source, implying that the media authority does not use its powers in an independent manner and in the interest of the public. We may say that in general the media authority is transparent about its activities and accountable to the public.

The indicator of /universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet reached a medium risk (34%). In this area, there are improvements to be made in particular in terms of broadband subscription and also in the average Internet connection speed. The Portuguese Parliament Resolution no. 11/20125 recommends the universal coverage of digital terrestrial television (DTT) signal. The Government must adopt the necessary measures to ensure universal coverage of the digital signal, either by digital terrestrial television (DTT) or by satellite at no extra charge for viewers, thus ensuring that there are no excluded citizens, particularly for economic reasons. Thus, PSM channels (all platforms included: DTT, Cable, Satellite, other) have a 99% coverage rate in households. With regard to the concentration of ISPs in the country, the percentage of market shares of the TOP 4 ISPs is almost 100%. Portugal does not yet have regulatory safeguards regarding Internet neutrality.

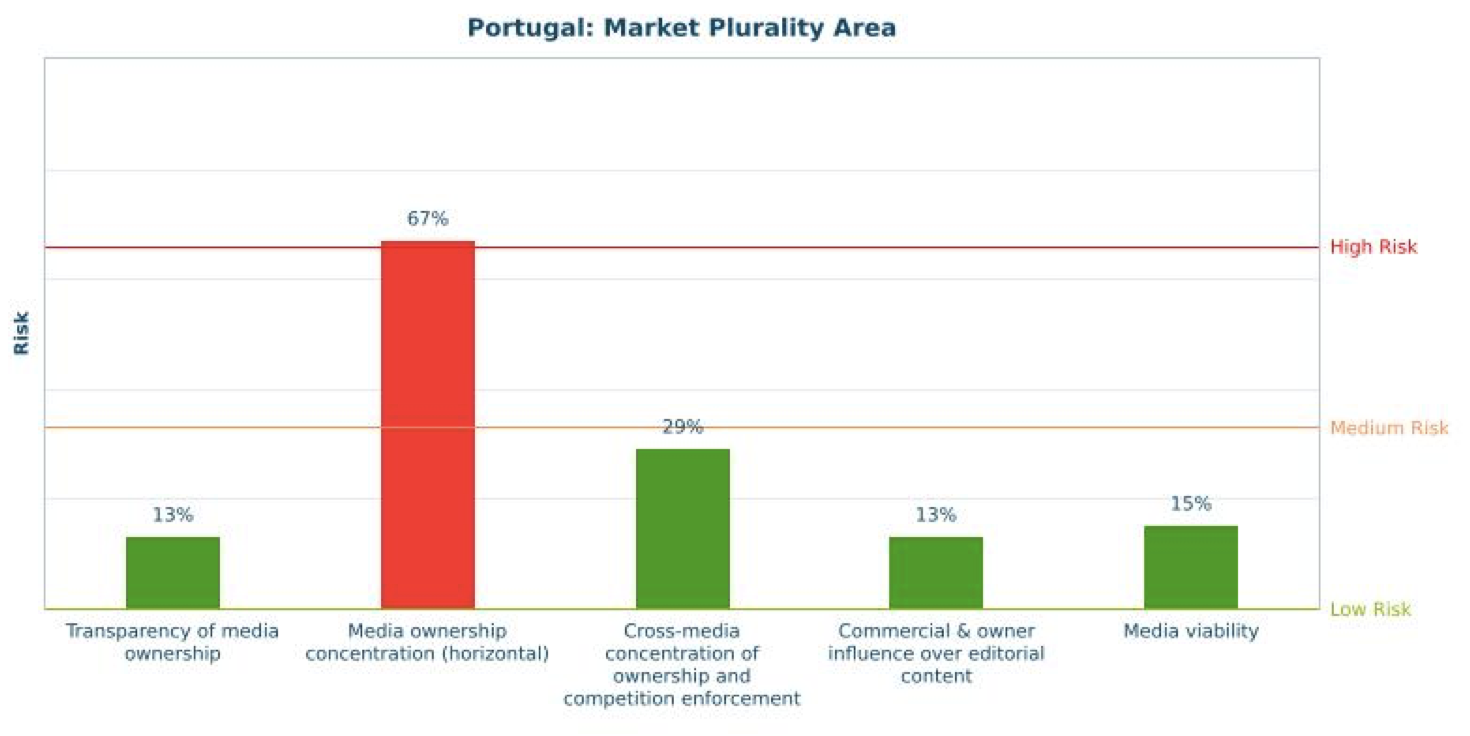

3.2. Market Plurality (27% – low risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

A very recent law (Law no. 78/2015) regulates the transparency of ownership across all media markets. This law includes transparency obligations (e.g. disclosure provisions) requiring media companies to publish their ownership structures. The law provides sanctions in cases where media companies do not comply with transparency obligations. The indicator of Transparency of media ownership is therefore 13%, revealing very low risk. However, one problem that persists is that there is no specific law for media concentration and there are no objective thresholds for cross-ownership of different media. Mergers and acquisitions between media corporations are analysed (case-by-case) by the competition authority (AC) and the media authority (ERC).

The laws that rule ownership are implemented within each media sub-sector. In the television sub-sector there are thresholds based on objective criteria. The television regulation mentions quantitative standards. The radio sub-sector also has several specific thresholds or limits, based on objective criteria. In contrast to television and radio, the press sub-sector is based on “laissez-faire” principles and policies. Press laws do not establish specific limits or thresholds for this sub-sector, and regulation considers qualitative, but not quantitative, standards.

Inside all the mentioned sub-sectors, excessive horizontal concentration of ownership can be prevented via general competition rules that take into account the specificities of the media sector. The competition authority (AC) and the media authority (ERC) can intervene, if necessary. The indicator of Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement scored 29%, showing a low risk, but bordering medium risk. A general media concentration law would probably lower the risk level.

The Portuguese traditional media markets have, in the majority of cases, an oligopolistic structure, with three or four dominant operators/groups. The major private-owned media groups are Impresa, Cofina, Media Capital and Global Media and there is also a state-owned group that operates in television and radio markets (RTP).

The indicator of Media ownership concentration (horizontal) reveals high risk (67%). The situation is of concern and must be monitored in the future by the regulator (ERC). However, in this indicator, we must take into consideration the small dimension and GDP of the Portuguese economy that limits the number of competitive operators.

It is currently very difficult to estimate market shares in the press sub-sector, because no complete and/or up-to-date data is available for several corporations. In the last years, a few operators did not comply with information obligations. This is a severe limitation to a rigorous evaluation of the horizontal concentration levels in Portugal.

In terms of Commercial and owner influence over editorial content, the level of risk is very low (13%). There are legal provisions that protect journalists from commercial or other economic influences. The regulatory framework prohibits advertorials and stipulates that the exercise of the journalistic profession is incompatible with any activity in the field of advertising.

In the last two years, media companies struggled to obtain positive revenues and reinforce their balance sheets in the fragile situation of the Portuguese economy. The financial information available is still too scarce to allow solid conclusions in this area.

The online market is growing, with increased advertising investment, but the revenues obtained in the new media platforms are scarce and risky. Almost all Portuguese media groups are diversifying their online services offer (not only providing information). Custom publishing and other marketing services are very common activities, which help to stabilise companies’ finances.

The government usually transfers funds to the PSM. There is no licence fee, but Portuguese households pay a contribution to RTP in the electricity bill. There are also State incentives to private local/regional media. The current unbalanced condition of the government budget has restricted this type of intervention.

The indicator of Media viability reveals low risk (15%). But a more complete assessment will only be possible as more economic and financial data is available this year.

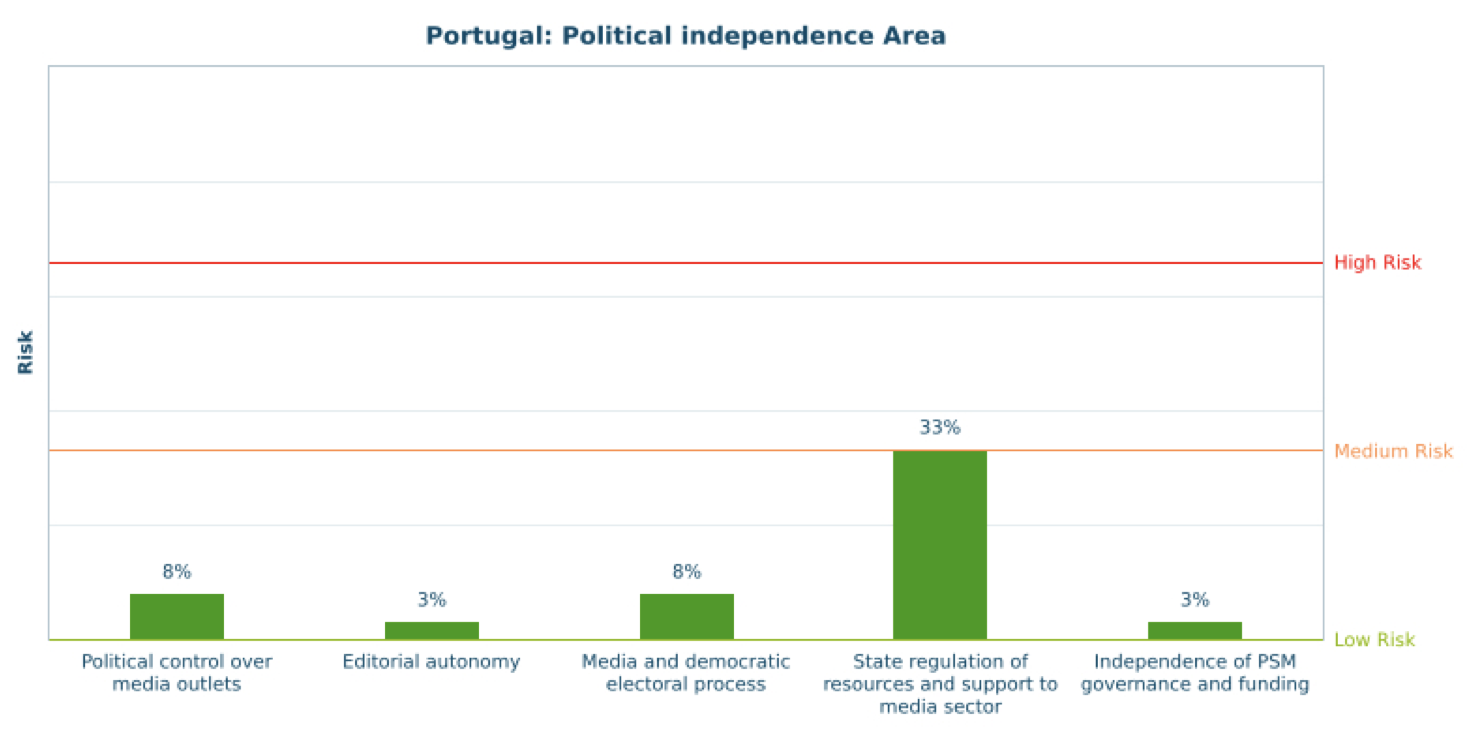

3.3. Political Independence (11% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicator of Political control over media outlets scores a low risk (8%). In Portugal the regulatory safeguards6 prevent governmental entities, ruling political parties, partisan groups and politicians from having media ownership. There are no reported cases regarding a conflict of interest situation between media owners and political leaders. Media laws contain several safeguards against the control of television and radio channels by politicians or political parties. Furthermore, in practice, there is no clear evidence – or proof of existence – of direct or indirect political control over audio-visual media. But there are some occasional cases of political control over the newspapers, mostly at the local and regional level. Also, there are some reported cases of lack of transparency and state advertising dependence that weakens the independence of the local and regional press.

Concerning the indicator of Editorial autonomy (3% – low risk) and the existence of regulatory and self-regulatory measures that guarantee freedom from interference in editorial decisions and content, media laws prevent political influence over the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief that could harm editorial independence. There are also self-regulatory measures that stipulate editorial independence in the news organizations. The largest media outlets in each category (TV, radio, newspapers) have a self-regulatory measure in place. In some cases the outlets have specific codes for online news7 but the media system and ERC assume that an editorial statute is valid for both online and offline. In our view the self-regulatory instruments that guarantee editorial independence are effectively implemented and editorial content is largely independent from political influence. Very few cases could be referred but do not change our understanding that this is a low-risk category.

With regard to the Media and the democratic electoral process, there are regulatory safeguards that guarantee and effectively implement a fair, proportional and unbiased representation of different political actors and viewpoints on PSM and private channels and services – namely in the news and informative programmes and especially during the electoral campaigns. Portuguese legislation also has regulatory safeguards that prevent political advertising (TV Law no. 27/2007, Article 31). During the electoral campaign period, the media should observe balance, representativeness and equity in the treatment of news, reporting of facts or newsworthy events related to the various candidates, adjusted to the effective possibilities of coverage.

Even though it scores a low risk (33%), the indicator of State regulation of resources and support to the media sector is on the border with medium risk and therefore, for Portugal, suggests the biggest concern within this area. With regard to the radio spectrum, fair and transparent management of spectrum allocation is lacking. Currently there are several spectrum problems with DTT in particular there is, in many places, a weak TV signal reception. The AdC (Competition Authority) in accordance with Article 62 of the Competition Law recommends the development of the necessary steps to increase the availability of a larger number of open channels, public and private. In 2015, a new policy of subsidies for regional/local press was implemented in order to promote partnerships between local and national media, in aspects such as technological innovation and training. Another aim is to develop a more articulated policy with other subsidies supported by European funds. Lastly, there is no evidence of non-transparent rules or situations regarding the distribution of state advertising in Portugal.

The indicator of Independence of PSM governance and funding scores a low risk (3%). In general, the existence of fair and transparent appointment procedures (in terms of incompatibilities, powers, rights and duties, duration and renewal of mandates, etc.) for management and board functions in PSM that guarantee independence from government or other political interference is ensured, and implemented effectively. Among the powers of the CGI – Independent General Council8 (CGI is composed of six members: two are appointed by the government, two by the Opinion Council of RTP and two are co-opted by the previous four) – is precisely the appointment of the executive management of public Radio and TV. Despite a recent change of government (now socialist) the PSM administration appointed by the previous government (liberal and rightist) remains in power. Further, the law prescribes transparent and fair procedures in order to ensure that the funding of PSM is adequate. Public radio and television broadcasting services are financed through the collection of an audio-visual contribution (paid on the electricity bill of each household) and by the commercial revenues of the services provided.

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (46% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The indicator of Access to media for minorities scores medium risk (50%). Minorities’ access to media is safeguarded by Portuguese Constitutional Law and monitored by the Television Public Service Contract, with mandatory programming hours dedicated to minorities’ issues and representation.

There are no political parties with a racist rhetoric, and right wing extremism is a marginal phenomenon in the political scene. Citizens of 170 nationalities now live in Portugal, comprising 4% of its population, and there are no significant cases of racism, xenophobia or discrimination towards migrants. The Government proposed recently to revise the Anti-Discrimination Law, reinforcing the concept of discriminatory practices and aggravating penalties. This context does not exclude the need to reinforce a more comprehensive programming to promote cultural diversity and to reduce the visibility gap of specific ethnic groups. Following the release of the last report about Portugal from the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination9, representatives of 22 NGOs argued for the adoption of specific measures aimed at people of African descent. NGOs are particularly concerned about the increase of reported cases of police abuse and the low number of condemnations.

Roma people are still the most vulnerable ethnic community facing media invisibility and biased coverage. Our recommendation is the development of monitoring systems and more academic research focused on media and minorities. Another priority is the promotion of a journalistic professional culture committed to giving visibility to migrants and ethnic groups and to fighting hate, assuring systematic and in-depth coverage. However, we do not consider this to represent a high-risk situation for minorities’ access to media.

The indicator of Access to media for local and regional communities and for community media scores medium risk (54%). The state incentives to the social communication sector was revised in 201510 and puts great emphasis on the need to make the digital the catalyser of regional and local media towards modernization and economic sustainability. The Coordinating Commissions for Regional Development are in charge of the management and allocation procedures regarding media companies’ incentives in four areas: digital development; access to the media; development of strategic partnerships; and media literacy. The Professional Training and Education Institute is in charge of the incentives concerning employability, promotion, training and skills development for regional and local journalists. The legal framework encourages regional-national partnerships.

The Portuguese regional and local press has a tradition of economic fragility and political dependence and there is a deficit in terms of recent independent evaluations regarding the effects of the digitalization process. The Concession Contract for the Public Service of Radio and Television11 stipulates the obligation to produce programme services specifically aimed at the archipelagos of Azores and Madeira and with a regional scope. This includes regular news services and informative programmes with a regional and local focus. However, the scope, quality and adequacy of these programmes are not well monitored and there is no data concerning the ways it could affect civic participation or better governance. There is no tradition of community media in Portugal and the format is not legally defined. We understand this could represent a potential risk but there is no reliable data to access this indicator.

The indicator of Access to media for people with disabilities scores low risk (25%). The Digital Portugal Agenda12 puts great emphasis in the accessibility and digital inclusion thematic. The obligation to take into account the special needs of people with disabilities is part of the licence agreement and mandatory for the registration process. PSM are obliged to produce a minimum of hours of emissions with subtitling, audio description and signing. Video searching, double screen and vocalisation are available on the PSM website. The on-demand audio-visual services obligations remain to regulate in terms of minimal standards, since they are not included in the multiannual plan negotiated between ERC and the stakeholders. The ERC recommendation is that all generalist open signal channels should offer a minimal amount of weekly programming hours with audio description, subtitling and signing, ranging from 35 hours to 3 hours, depending on the genre: fiction, documentaries or informative.

The indicator of Access to media for women scores medium risk (44%). Gender labour equality is guaranteed by national and communitarian legislation13. PSM companies are bound by additional obligations, limiting the access to public funding if a gender equality policy is not followed regarding recruiting and training opportunities. The annual auditing of ERC relies on two instruments: the PSM auditing reports and the regulatory reports, which also include the private television channels. Data indicates that gender imbalances in society are reflected in the media e.g. through underrepresentation of women or biased coverage. Elderly women, women from minority ethnicities and religious groups or women with different sexual orientations are continuously underrepresented in the media. The coverage of gender issues tends to be problematic regarding the spectrum, the depth and the angle of coverage.

The indicator of Media literacy scores medium risk (56%). The media literacy policy is aligned with European standards, namely the European Council Conclusions on Literacy, but fragmented and dispersed in the field and lacks national coordination. Digital inclusion data show an improvement of literacy skills and a reduction in Internet exclusion, but the elderly population remains vulnerable.14 Despite the increasing use of digital technologies during teaching activities, research shows15 that Portuguese students rely more on private resources than school support to acquire digital literacy. There is a need to build a stronger focus on media literacy into curricula and to provide more cognitively demanding literacy instruction in schools.

4. Conclusions

The present national report does not provide major revision to the findings of the MPM2015. The legal and institutional framework remains basically unchanged and the expected improvements are similar to the ones previously stated.

There are two main issues in this area: a strong need to monitor a potential loss of journalists’ autonomy regarding interest groups and the economic system; and the increasing impact of digital intermediaries over citizens’ access to information. It is also important to consolidate DTT in Portugal, improving the offer of channels, currently limited to only seven channels. Fostering legislation about “net neutrality” should be also a priority.

As regards Market Plurality, the situation of Portugal is globally positive and does not raise major concerns. However, in order to address potential problems of cross-media concentration (such as abuse of market position), the Portuguese political agents should work towards a consensual law in this area. The current high levels of horizontal concentration are acceptable, considering the scarce resources and the small size of the media market. However, to prevent potential problems, the regulatory authorities (AC and ERC) must carefully monitor the behaviour of market operators (for example, in terms of transparency of ownership).

Since the 2017 state budget continues to ensure the collection of the audio-visual contribution and its immediate delivery to RTP management (delivered monthly by the tax authority to RTP), the public operator maintains full capacity in this topic. A clear assessment of the mission requirements performed by RTP in the dimensions of pluralism, inclusion and informative content independence require complementary studies based in content analysis (developed preferably by the Academy and its research centres)

In the area of Social inclusiveness Portugal needs to create more instruments to think critically about ethnicity in the media, and promote more studies and reports about media representations of different ethnic groups in entertainment, advertising and news media. The investments in e-Government platforms and communication infrastructure must be combined with initiatives that help digitally excluded populations to experience the benefits of digital services. More digital devices should be incorporated into the school and more ICT–based activities should be planned in order to create a more favourable environment in terms of media and digital literacy.

Finally, we believe that it is important to introduce an in-depth debate with all of the parties concerned – media, regulators, academy, etc. – on the issue of regulation in the media sector. In a small market such as the Portuguese, either because of Internet-related issues or because of issues concerning business proximity between Telcos and media operators, the option for a single regulator for communications and the media may be justifiable in our opinion.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Francisco Rui | Cádima | Full Professor | Universidade NOVA de Lisboa | x |

| Carla | Baptista | Assistant Professor | Universidade NOVA de Lisboa | |

| Luís | Oliveira Martins | Assistant Professor | Universidade NOVA de Lisboa | |

| Marisa | Torres da Silva | Assistant Professor | Universidade NOVA de Lisboa |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Adelino | Gomes | Representative of a journalist organisation | General Council of the Journalists Union |

| Alberto | Carvalho | ERC’s Vice-President

|

ERC |

| Estrela | Serrano | President | CIMJ |

| João | Palmeiro | President | API – Associação Portuguesa de Imprensa |

| Miguel | Poiares Maduro | Professor | European University Institute

|

| Paula | Cordeiro | Assistant Professor | ISCSP |

| Paulo | Faustino | Professor and researcher | Porto University |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] See “3rd Report submitted by Portugal on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities” (Council of Europe, September 2013). reporthttps://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=090000168008b7c7

3 AAVV (2014) Informação e Liberdade de Expressão na Internet e a Violação de Direitos Fundamentais, Lisboa: IN-CM, p. 96.

[3] APRITEL (The association of private telco operators). “Memorando de Entendimento”. See: https://sitesbloqueados.pt/memorando-de-entendimento/

5 Portuguese Parliament Resolution No. 11/2012 – Universal coverage of digital terrestrial television signal (DTT and Satellite). Diário da República, 1st series – No 26 – February 6.

6 Constitution of The Portuguese Republic, seventh revision [2005]. Article 38 (Freedom of the press and the media), no. 3, 4 and 6.

7 Grupo Media Capital – Código de Conduta na Web 2.0:

https://media.iolnegocios.pt/media1201/03f3bd74ee3ef8b8a87de434cc7934d4/.

See also Público – “Público, Termos e Condições”: https://www.publico.pt/nos/termos-e-condicoes.

8 CGI is composed of six members: two are appointed by the government, two by the Opinion Council of RTP and two are co-opted by the previous four.

9 Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (2015). Fifteenth to seventeenth periodic reports of States parties due in 2015 – Portugal. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G15/261/85/PDF/G1526185.pdf?OpenElement.

10 Decree-Law no. 23/2015. Approves the new regime of incentives of the State to the media. Diário da República no. 26/2015, Series I, 06/02/2015. https://data.dre.pt/eli/dec-lei/23/2015/02/06/p/dre/en/html.

11 See: https://media.rtp.pt/institucional/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2015/07/contratoConcessao2015.pdf.

12 See: https://portugaldigital.pt/index/.

13 Igualdade de Género, Cidadania e Não-Discriminação: https://www.cig.gov.pt/planos-nacionais-areas/cidadania-e-igualdade-de-genero/

14 The main indicator monitored is the rate of non-Internet users (by the national statistical institute [INE] and Eurostat). This was fixed at 33% in 2013, falling to 28% in 2015, a number that is still above the EU average. The Internet-excluded are typically the elderly, the economically deprived and the less educated groups in the population.

15 Paula Lopes et altri (2015). “Avaliação de competências de literacia mediática: o caso português”. Revista Observatório, Palmas, v. 1, n. 2, p. 42-61, Sep./Dec. https://cld.pt/dl/download/9550c7ca-bd03-4313-b853-8d67b294d8b4/avaliacao_literacia_media.pdf.