Malta

Download the report in .pdf

English

Author: Iva Nenadic[1]

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection for Malta was carried out centrally by the CMPF team between May and October 2016. A group of national experts was interviewed to ensure accurate and reliable findings, and to review the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the details on procedure and list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[2].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the EC.

2. Introduction

Malta is an island country located in the Mediterranean Sea, in the passageway between Africa and Europe. The three largest islands of the archipelago are inhabited – Malta, Gozo and Comino. With an area of just 315 sq. km and the total population of 429,344 (end December 2014, NSO), it is one of the world’s smallest and most densely populated countries. Maltese and English are two official languages, but Italian is also widely spoken. There are no minorities recognized by law. The migration flux that affected Malta much earlier[3] than the other EU countries increased the number of North African Muslim Community (Grixti, 2006[4]). However, most of the foreign community in Malta still consists of British nationals (10,480, NSO 2011). Even though the number of migrants reaching Maltese shores declined sharply in 2015 (Amnesty International, 2015/2016)[5], Maltese people still see immigration as one the most important issues facing their country at the moment (Standard Eurobarometer 85, 2016). There is a lack of comprehensive research on media representation of different minorities and/or communities, particularly considering, for example, the representation of Muslim community in predominantly Roman Catholic society (some estimates suggest that more than 90% of the population are Roman Catholic, e.g. Grixti, 2006).

Malta is a parliamentary republic with two major political parties alternating in power. Since 2013 the country is governed by the social democratic Labour Party (Maltese: Partit Laburista, PL), leaving Christian democratic Nationalist Party (Partit Nazzjonalista, PN) in the opposition. The Maltese government found itself in an international focus after one of the ministers and the prime minister’s chief of staff were mentioned in the Panama Papers leaks in April 2016[6].

Malta is an EU member state since 2004. The most important sectors of the country’s economy in 2015 were wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation and food services (22.6%). Economic performance has been robust in a challenging macroeconomic environment over the past several years (EC, 2016). Real GDP growth recovered relatively quickly following the 2009 recession, well above EU average (Eurostat, October 2016).

In Malta as in most other EU countries, television is still the main and most trusted source of news on national political matters (Standard Eurobarometer 84). There are three most relevant television broadcasters: public Television Malta (TVM) and two stations owned by the political parties (NET TV by the NP, and the TV ONE by the LP). They mainly operate in Maltese language. According to the Standard Eurobarometer (84, 2015) Malta is well above the EU average for online usage with 32% of population getting informed via online social networks. Half of respondents use them on a daily basis, but they are still not considered as reliable as legacy media (EBS 452). Even though its social influence is not as strong as it used to be, the Roman apostolic Catholic Church is still a relevant player in the media market through its own radio stations, weekly newspaper Lehen and online media (Aquilina, 2014). Furthermore, many community radio stations, particularly in Gozo, broadcast Catholic religious content.

The 2016 World Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders places Malta at 46h position, two higher than the previous year. The main remaining issues are related to defamation which is still punishable by fines or imprisonment and broadly used especially by politicians. Moreover, the law penalizes vilification of religion.

According to the Special Eurobarometer (452, 2016) on Media pluralism and democracy, respondents in Malta see their national media as more free and independent (48%) and providing more diversity of views and opinions (47%) compared to five years ago.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

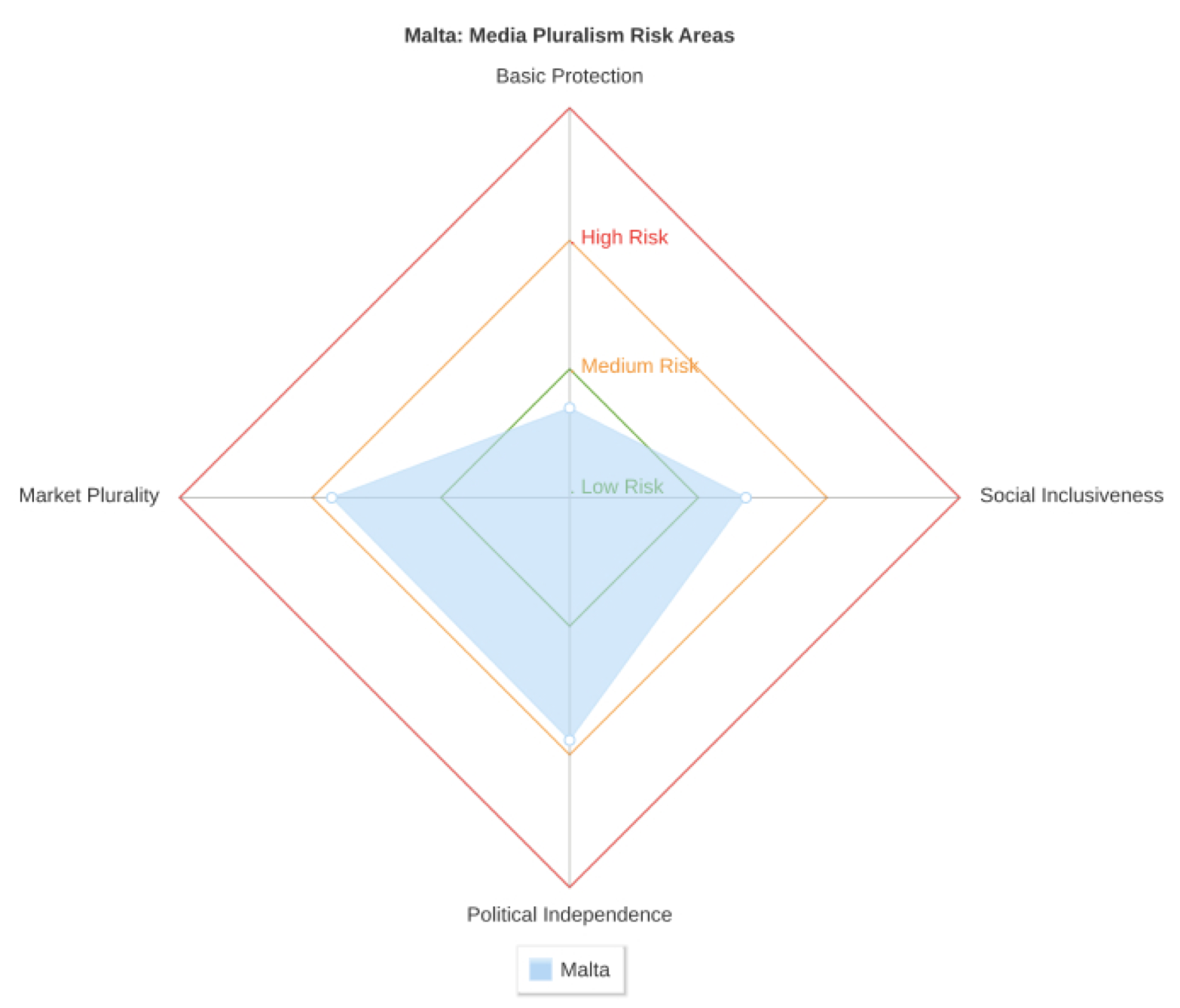

The implementation of the MPM2016 for Malta overall shows medium risks for media pluralism. A low risk was detected in the area of Basic Protection, a medium level of risk was found in the area of Social Inclusiveness, while Market Plurality and Political Independence areas scored medium, close to high risk. Most of the risk-increasing factors relate to lack of data on media market, lack of protection and self-regulation of journalists and editorial autonomy, direct political ownership of media outlets and lack of media literacy policy.

Small media markets are usually concentrated but the main cause for risks on concentration of media ownership in Malta emerge from the fact that the data on revenues is not available nor collected by national authorities. However, media ownership is quite transparent and unique in the EU environment considering that two major political parties in the country are amongst the key players in the media industry. There is also a political influence, mainly from a party in government over the public service media. Journalists in general are not well protected and efficiently organized in order to prevent both political and commercial interference with editorial autonomy.

With the availability and prevalence of new communication technologies, media convergence and new sources of news, increasing media literacy of the general population should be among key priorities of media policies. Malta is one of the few countries in the EU that until the completion of the MPM2016 data collection did not have media literacy policy, media literacy was absent from the compulsory education curriculum and only some fragmented activities limited to Church schools and certain groups, usually youth, were noted.

3.1. Basic Protection (23% – low risk)

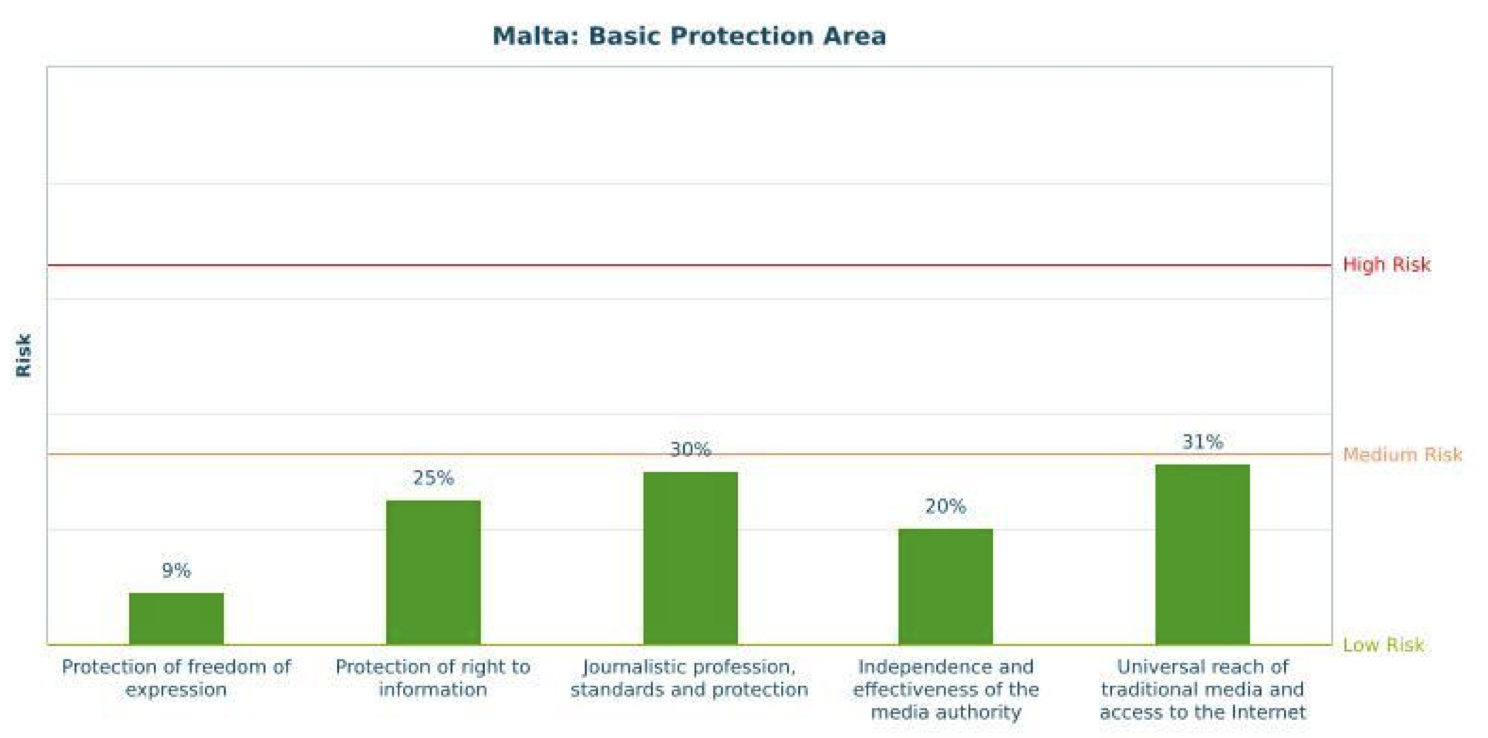

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

All indicators in the area of Basic Protection score as low risk, with the indicator on Protection of freedom of expression scoring the lowest (9%). Freedom of expression is guaranteed in the Constitution, and Malta has ratified the relevant conventions which guarantee freedom of expression (although with reservations). Experts also claim that, in practice, during the 2015-2016 period there was no evidence of violations of freedom of expression, either online or offline. However, considering that religion has an official influence on legal regulation of freedom of expression and that politicians enjoy high level of protection against defamation (Lazariev, 2015), criminalisation of defamation and blasphemy could contain a risk to the exercise of freedom of expression, mainly by imposing self-censorship.[7]

Protection of the right to information overall scores a low risk (25%). Access to information is currently guaranteed by the Constitution and by the specific law. The Freedom of Information Act was enacted in December 2008, but it was fully brought into force in 2012. This was attributed to the Maltese tradition of public administration to withhold information rather than to be proactive and make information available (The Parliamentary Ombudsman Malta, 2015). The MPM2016 investigation indicates that journalists sometimes have problems accessing information from the government. Access to information requests and appeals are not effective in such situations, in particular for the daily media – these procedures are often prolonged and the information becomes outdated by the time it is revealed. Furthermore, FoI Act grants access to information to Maltese citizens, EU citizens and people who reside in Malta for a period of at least five years, excluding others (e.g. non-EU and not resident journalists, migrants, refugees).

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection also scores a low risk but close to medium (30%). In Malta there are no legal obstacles for any person to work as a journalist but the working conditions of journalists are affected by the decay of the media business model prompted by digital disruption. The risk assessment for this indicator mainly reflects poor protection from the owners’ and advertisers’ influences. As suggested by interviewed experts, journalists and editors working in party media are under obvious influence from the owners, and the economic pressures from advertisers are rising. This is even more problematic since the only professional organisation, the Maltese Institute of Journalists, is not considered as effective in safeguarding editorial independence.

Further risks for media pluralism in this area stem from political influence in the appointments of the board members of the Broadcasting authority that monitors and regulates radio and television broadcasting in Malta. The Chairperson and four members are appointed by the political decision and agreement: two members are selected by the prime minister, two by the opposition, while chairperson is generally decided upon the mutual agreement. Broadcasting Authority focuses on regulation of the Public Broadcasting Services and does not interfere much with activities of the other two leading broadcasters owned by two major political parties – Net TV and Radio 101 (Nationalist Party), Super One Radio and ONE TV (Labour Party). General view of the Authority is that the sole existence of the two stations owned by political parties contributes pluralism and therefore it is more important to ensure impartiality of public broadcaster. Majority of cases or disputes reported by the Authority relate to advertising and there, the Authority acts impartially. An overall risk assessment for the indicator on Independence and effectiveness of the media authority is low (20%).

Finally, the entire population has access to PSM channels, and broadband is available to the rural population, so there is also a low risk with regard to Universal coverage of PSM and the Internet (31%). It should, however, be noted that the percentage of broadband subscriptions is below the EU average.

3.2. Market Plurality (61% – medium risk)

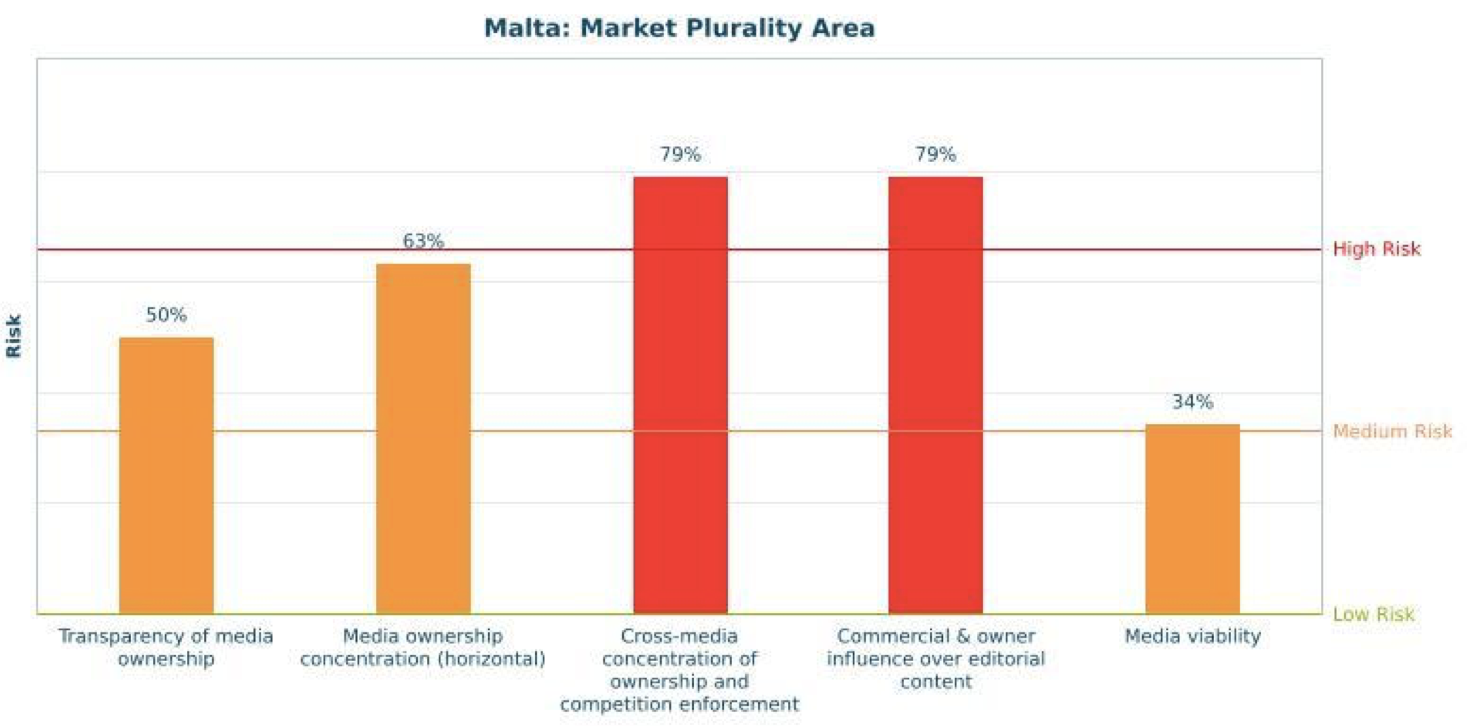

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Malta scores a medium risk in the area of Market Plurality with two indicators in the high risk band: Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement and Commercial and owner influence over editorial content.

Transparency of media ownership is assessed as a medium risk indicator (50%) albeit, according to the experts’ opinions, the public is well aware of who owns which media in Malta. Risk, however, reflects the fact that there are no specific legal obligations whereby media companies are required to publish their ownership structures on their website or in documents that are easily accessible to the public. Like every other company, they must register with the Registrar of Companies (RoC) by submitting a memorandum of association which must, inter alia, include the name and residence of each of the shareholders. RoC is available online but the details that are accessible to the public for free are very limited. The Broadcasting Authority is entitled to require and obtain any type of information it considers necessary from the license holders. However, the Authority does not publish this information on its website.

The data shows that Malta has highly concentrated markets, since the Top4 media owners in the major media sectors (audiovisual and radio) have more than 50% of audience share. The legislation regulating horizontal concentration in audiovisual and radio markets, and its apparent effectiveness, decrease the risk assessment. Therefore, Media ownership concentration (horizontal) scores medium risk but very close to high (63%). It should also be noted that the print market is unregulated and no data is collected about newspapers concentration and circulation.

Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement acquired 79% of risk which is one of the highest in this area. This is mainly due to the lack of sector specific legal provisions that would allow the competent authorities to enforce competition rules, and the nonexistence of regulatory safeguards against disproportionate State aids to public service media. According to the Broadcasting Act (amended in 2010), a provider of a nationwide radio or television service, including the provider of public broadcasting services, may not own, control or be editorially responsible for a community radio service. The Broadcasting authority takes this into consideration when issuing licenses. There are no provisions that would allow the competent authorities to enforce competition rules in a way that takes account of the specificities of the media sector. However, consumer interests constitute one of the evaluation criteria against which the Director General of the Malta Competition and Consumer Affairs Authority may determine whether a concentration is compatible with the Regulations’ provisions (Article 4(2)(d)). These criteria therefore apply also to the media sector. Nevertheless, it has to be noted that the print and online media markets are unregulated, and no data is collected about either them or their concentration. Therefore, there is no available information on Top4 owners across different media markets.

The other indicator which scores high risk is concerned with the Commercial and owners influence over editorial content (79% risk). The analysis has shown that there are no specific mechanisms granting social protection to journalists in case of changes of ownership or editorial line. Moreover, there is no specialized trade union representing journalists and taking care of their working conditions. There are also no safeguards to prevent influence of commercial interests over the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief. Although there is a law prohibiting advertorials, experts suggest that it is not effectively implemented and that hidden advertising in the media sometimes occur.

Media viability indicator scores medium risk (34%) mainly because there is no data available on the revenues of different media sectors, which increases the risk. On the other side, the risk is still in the medium risk band because there is a steady increase of the use of internet and mobile devices among individuals.

3.3. Political Independence (62% – medium risk)

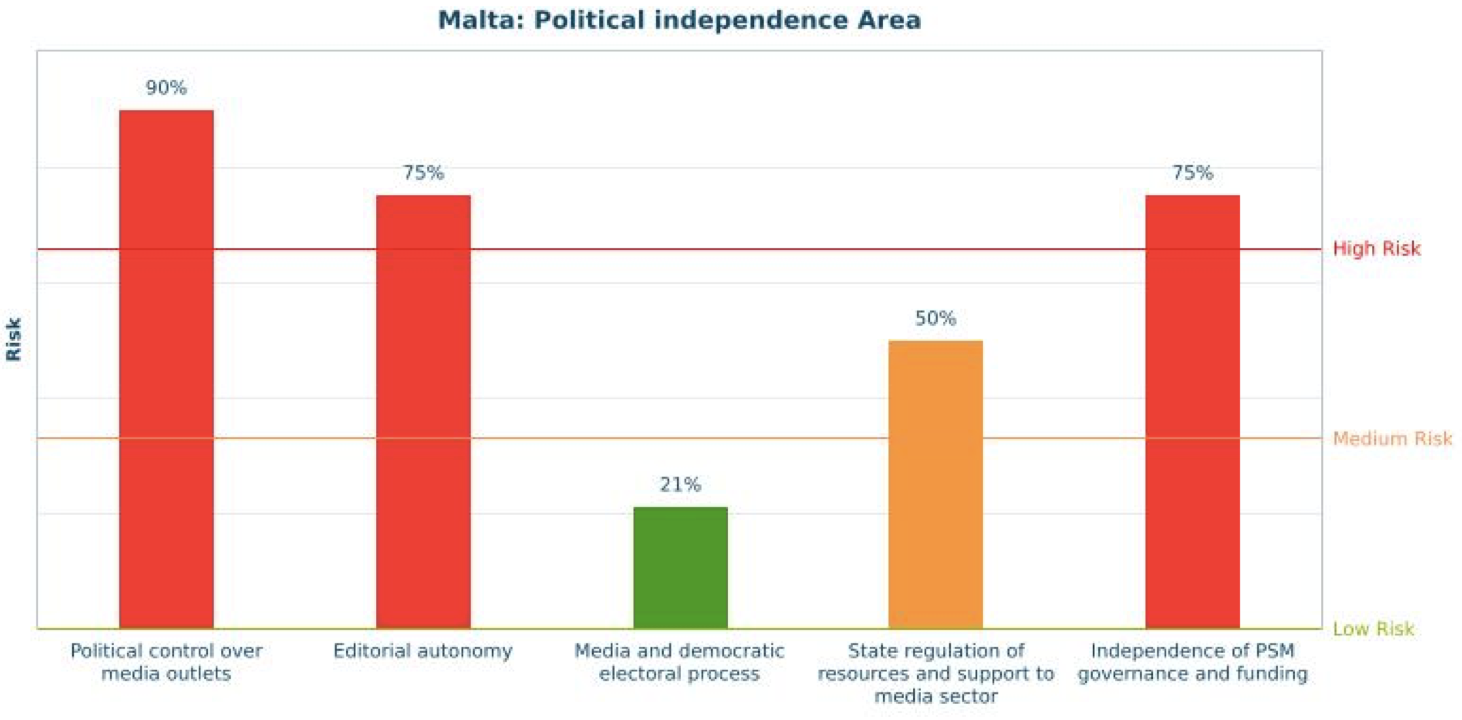

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The Political Independence area scores a medium risk overall but with three indicators being at high risk: Political control over media outlets, Editorial autonomy and the Independence of PSM governance and funding.

There is no law that makes government office incompatible with media ownership. Government is allowed to own, control or be editorially responsible for nationwide television and radio services, under certain conditions (Broadcasting Act, Part III, 4D). Therefore, both political parties represented in the House of Representatives own, control and manage their own media enterprises consisting of different media outlets, publishing house and mobile telephony (Aquilina 2014: 151, interviews in Malta in June 2016). Nationalist Party owns NET TV, Radio 101, daily newspaper In-Nazzjon Taghna (Our Nation) and weekly Il-Mument (The Moment), while the currently governing Labour Party owns One TV, One Radio and weekly Kulhadd (Everybody). Malta is the only EU country that has such extensive media ownership by the political parties. For this reason the indicator on Political control over media outlets acquires 90% of risk, which is the highest in this area. However, some experts interviewed in Malta argue that, in comparison to other EU countries, political parallelism in Malta is just more transparent and ensures that different political viewpoints are represented in the media system. There is more concern about the indirect and non-transparent political influences over PSM.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy also scores a high risk (75%) mainly due to the lack of regulatory and self-regulatory measures that safeguard editorial independence in the news media. The Code of Ethics of the Institute of Maltese Journalists is outdated and the new one was not adopted during the MPM2016 implementation. Few news outlets claim to have internal codes of conduct but these are not publicly available. Although there is no hard evidence, experts largely agree that there are attempts of political influence on appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief and over the editorial content.

Particularly vulnerable to political influences is the PSM. The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding scores a high risk (75%). The analysis has shown that the government has a big influence on PSM governance by appointing members of both its Managerial and Editorial boards. The government also partially funds the PSM via a direct grant, which is transparent, but the amount of the grant is decided by the government at its own discretion.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a low risk (21%). Fair representation of different political actors and viewpoints is mandated by law and is monitored by the Broadcasting Authority, in particular during the electoral campaigns. These principles are mostly respected. Interviews did indicate occasional pro-government bias in general PSM reporting, but most experts agree that there is a mathematically balanced representation of two major political sides, and the content analysis to provide additional evidence is not available.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector scores a medium risk (50%), mainly because there is no legal framework nor transparency in the allocation of state advertising. It has been noted by the national experts that the government uses state advertising in pre-election period, but also all year round, as a form of political advertising to channel money to certain media outlets.

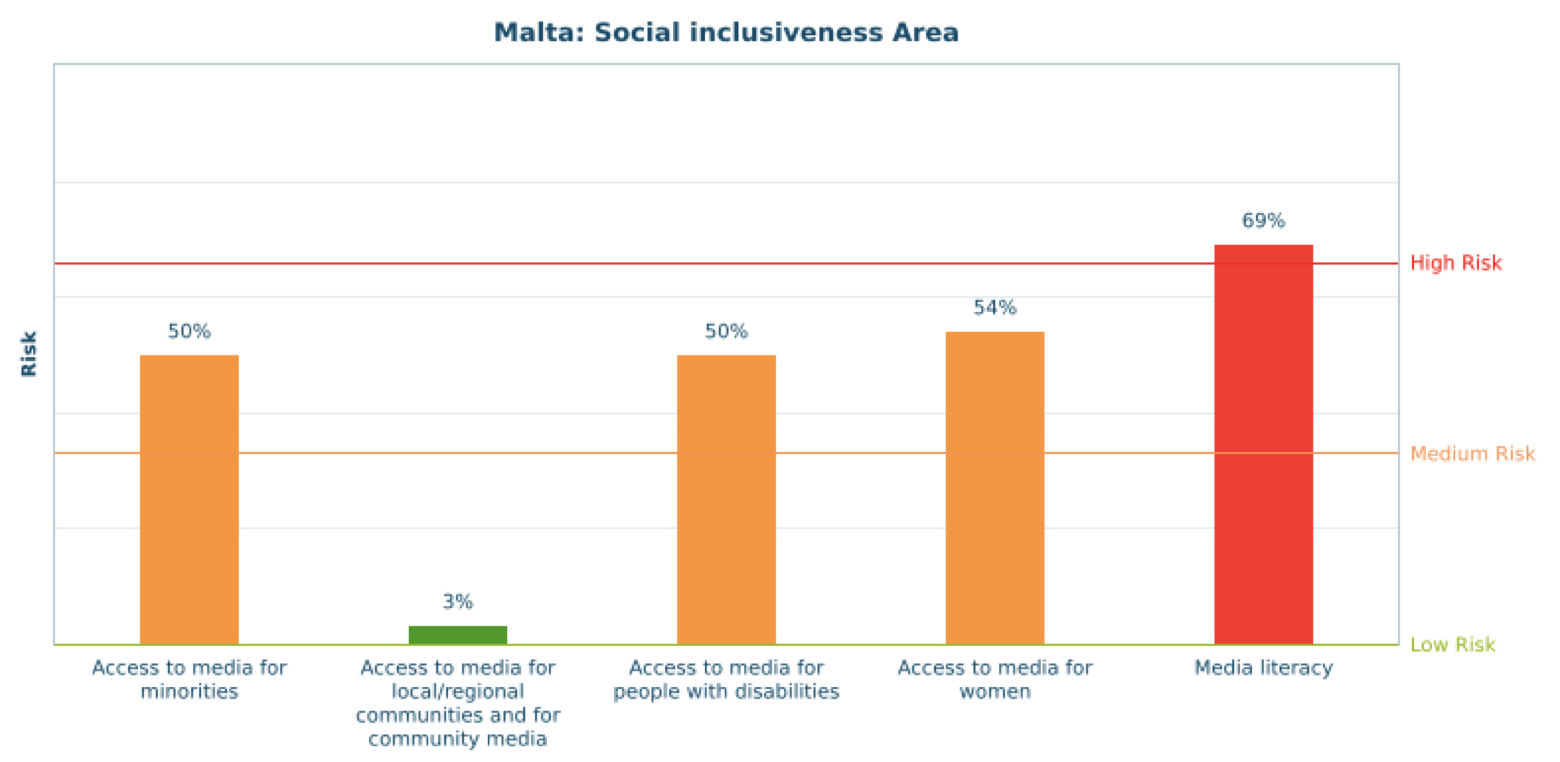

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (45% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The Social Inclusiveness area scores a medium risk, with only one indicator in the high risk band – the one on Media literacy (69%). Malta is one of few countries in Europe that to date has no policy on media literacy. According to the national experts, only some elements of media literacy are considered within certain subjects in the educational curriculum, and it is very dependent on teachers, their competences and motivation. As regards other activities in this area, they are dispersed and limited. Only Church schools have a long tradition of so called media education programmes that aim to increase students’ critical understanding of media structure, language and content.

Three indicators within this area score medium risk: Access to media for minorities (50%), Access to media for people with disabilities (50%) and Access to media for women (54%). There are no minorities recognized by law in Malta. Therefore, there are no specific provisions regarding the access to airtime for minorities. This however, does not mean that there are no minorities. According to the Standard Eurobarometer (85, 2016), Maltese people still see immigration as one the most important issues facing their country which makes media representation of minorities and willingness of the media system to provide them access to media of great importance. Still, there is a lack of comprehensive research on media representation of different minorities and/or communities. In general, the biggest language minority is the English speaking group (British, Australians, Canadians and Americans) but, together with Maltese, English is an official language and some of the most influential media in the country (newspapers) are published in this language (e.g. Times of Malta, The Malta Independent, Malta Today). No specific media for other minorities have been identified.

The indicator on Access to media for people with disabilities scores a medium risk (50%). In the past years, political debates and party conferences during electoral campaigns were accompanied by sign language translations (Broadcasting Authority Malta 2015). On the other side, audio descriptions for blind people are usually not available. The Broadcasting Act (16J, 3) stipulates that: “Media service providers shall encourage that their services are gradually made accessible to people with a visual or hearing disability”. Moreover, subsidiary legislation[8] made by the Broadcasting Authority in 2007 stipulates the following: “Broadcasters should aim to recruit disabled persons to work among their staff and in particular the portrayal of disabled persons in drama should wherever possible be carried out by disabled actors”. However, it is not clear who should monitor compliance with this request and whether it is respected so far.

Access to media for women also scores a medium risk (54%), mainly due the situation in practice. The Constitution of Malta (art.14) stipulates equal rights of men and women. There are also Equality for Men and Women Act (2003) and Employment and Industrial Relations Act (Chapter 452, 2002) which in Part IV prescribes ‘Protection against Discrimination related to Employment’. Furthermore, PSM has internal Equality Policy that focuses on personnel issues, but in a more general manner and without stating concrete objectives and tactics to achieve them. Women are not represented in the Editorial board of the PSM (Television Malta), and out of eight members of the Board of Directors (including chairperson and deputy chairperson), only two are women. Moreover, according to the data from Global Media Monitoring Project (2015), the presentation of genders in news is not balanced.

Finally, the indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores a low risk (3%), mainly because the Broadcasting Act gives a special recognition to the “community radio service”. The Act (Art. 10(9)) provides that community radio services must be subject to the minimum of regulation consistent with the public interest and to conditions which, taken together, are less onerous than those provided for nationwide radio services. The Broadcasting Act (6D) also stipulates the independence of community radio from local councils.

4. Conclusions

The implementation of the 2016 Media Pluralism Monitor in Malta generally shows a medium risk. The only area that scores a low risk is the Basic Protection, but with at least one matter of concern – lack of efficient professional organization and self-regulation of journalists. This is a precondition for professional independence, especially in such challenging times when working conditions of journalists are affected by the decay of media business model; and professional practice is being reconsidered in the context of increasing power of digital platforms. The Maltese Institute of Journalists (MIJ), the only professional journalists’ organization in Malta, is mainly run by volunteers in their very scarce free time. The new chairman of MIJ has expressed a willingness to modernize the organization, its scope and activities in order to (re)position as a relevant actor in the media system. However, the success of this attempt also depends on a broad support and engagement of journalists, media companies and authorities. So far, lack of efficient self-regulation reflects in high risks regarding editorial independence from both political and commercial influences.

The highest risks in the area of Market Plurality are largely related with the lack of monitoring and data on market shares of media companies and newspapers circulation, and in particular the lack of insights on online media. Considering that Malta significantly stands out from other EU countries when it comes to a number of people that get their news on national political matters firstly on social media (16%, while EU average is 3% – Standard Eurobarometer 84, 2015), co-ordination and communication between the three relevant authorities (Broadcasting Authority, Malta Communications Authority, Malta Competition and Consumer Affairs Authority) should be improved to provide accurate monitoring of online media market and all relevant actors.

Most at risk for Malta is the area of Political Independence. Lack of Independence of PSM governance and funding was indicated as a particular issue of concern by consulted national experts. Currently, there are no guarantees of independence since both the Board of Directors and Editorial Board are directly appointed by the Government. Therefore, it is suggested to revise the legislation on PSM regulation and appointments procedure to include safeguards from political interference.

Malta is one of the few countries in Europe that to date have no policy on Media literacy. In order to empower citizens with critical understanding and skills needed for active participation in the contemporary information exchange, policymakers in Malta, as well as academia and media industry have to involve into inclusive discussion that will result in comprehensive and applicable media literacy strategy.

References

Amnesty International, Country Report: Malta 2015/2016. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/europe-and-central-asia/malta/

Broadcasting Act [Cap. 350] – Latest amended by Act XLII of 2016. Available from: https://www.ba-malta.org/legislation

European Commission (2016) Country Report: Malta – working document. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/csr2016/cr2016_malta_en.pdf or from: https://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/europe-2020-in-your-country/malta/country-specific-recommendations/index_en.htm

Eurostat (October 2016) Real GDP growth, 2005–2015. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/File:Real_GDP_growth,_2005%E2%80%932015_(%C2%B9)_(%25_change_compared_with_the_previous_year;_%25_per_annum)_YB16.png

Grixti, J. (2006) Symbiotic transformations: Youth, global media and indigenous culture in

Malta. Media, Culture & Society, 28(1): 105-122.

National Statistics Office (2014) Demographic Review. Available at: https://nso.gov.mt/en/publicatons/Publications_by_Unit/Documents/C3_Population_and_Tourism_Statistics/Demographic_Review_2014.pdf

National Statistics Office (2011) Malta: Census – Total population by country of birth: Census of Population and Housing

Reporters Without Borders (2016) World Press Freedom Index: Malta. Available at: https://rsf.org/en/ranking

Requirements as to Standards and Practice Applicable to Disability and its Portrayal in the Broadcasting Media (in virtue of article 20(3) of the Broadcasting Act, Chapter 350 of the Laws of Malta). Available from: https://www.ba-malta.org/legislation

Special Eurobarometer 452 (2016) Media pluralism and democracy – Country Factsheet: Malta. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/2119

Standard Eurobarometer 84 (2015) National Report: Malta. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/yearFrom/1974/yearTo/2016/surveyKy/2098

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is usually composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report. In the case of Malta, the data collection was carried out by the CMPF’s researchers.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Iva | Nenadic | Research Associate | European University Institute, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom | X |

| Konstantina | Bania | Research Associate (until 31 December 2016) | European University Institute, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The data collection for Malta was carried out centrally by the CMPF team applying three methods: desk research, requests for information, and in-depth interviews with selected country experts. The desk research provided a solid base for a general overview of the situation and the identification of key actors in the media market. Requests for information did not always work but did help to identify a risk of lack of coordination and cooperation between organizations related to media and, in general, lack of monitoring of media market in the country.

Between 5 and 10 June 2016, the CMPF’s researcher Iva Nenadic interviewed eight national experts in Malta to collect the data and to ensure accurate and reliable findings. During the interviews, national experts (listed below) were also asked to review the answers to particularly evaluative questions that are intended for the Group of Experts procedure (see more on this procedure in the Final Report – Methodology).

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Kevin | Aquilina | Dean | University of Malta, Faculty of Law |

| Joseph | Borg | Senior Lecturer | University of Malta, Media & Communications, Faculty of Media & Knowledge Sciences |

| Herman | Grech | Digital Media Editor | The Times of Malta |

| Alex | Grech | Visiting Senior Lecturer | University of Malta, Faculty of Media & Knowledge Sciences |

| Said | Pullicino | former Ombudsman | Parliamentary Ombudsman |

| Joanna | Spiteri | Head of Monitoring Department | Broadcasting Authority |

| Matthew | Vella | Editor | Malta Today |

| Karl | Wright | Chairman | Institute of Maltese Journalists |

—

[1] Konstantina Bania collaborated in the data collection.

[2] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[3] See: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/03/malta-migration-crisis-doctor-artist-engineer-blogger-human-stories-

[4] Note: These statistics are reproduced from the Word IQ encyclopaedia available at: https://www.wordiq.com/definition/Malta

[5] See: https://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2016-05-15/world-news/EU-Presidency-raises-concerns-as-migration-routes-shift-to-central-Med-6736157849 ; https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/03/malta-migration-crisis-doctor-artist-engineer-blogger-human-stories-

[6] See: https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20160927/local/panama-papers-konrad-mizzi-among-first-to-be-called-to-brussels.626294

[7] NOTE: The data collection for Malta was closed in October 2016. Therefore the indicator on Protection of freedom of expression does not reflect latest developments which will be assessed in the MPM2017: Journalist and blogger Daphne Caruana Galizia is having her bank accounts frozen with precautionary warrants for 47,460 EUR after a court upheld on 8 February 2017 a request by Maltese Economy Minister Chris Cardona and his consultant Joe Gerada to issue garnishee orders alongside four libel suits they have filed against her (CoE, 10 Feb 2017). In its reply to the complaint submitted by the international journalists organizations to the Council of Europe, Maltese Government distances itself from the civil libel actions filed in by the Minister and his consultant. The Government emphasizes its initiative to adopt a new law – Media and Defamation Act, that contains a prohibition of the use of precautionary warrants in actions for libel or defamation, and a revocation of criminal libel. However, the new law proposal introduces a new action of a civil slander and increases the maximum amount of damages which can be awarded in civil libel procedures by almost double. For more information see: CoE – Media Freedom Alerts (Malta)

[8] Requirements as to Standards and Practice Applicable to Disability and its Portrayal in the Broadcasting Media (in virtue of article 20(3) of the Broadcasting Act, Chapter 350 of the Laws of Malta). Available from: https://www.ba-malta.org/legislation