Germany

Download the report in .pdf

English – German

Authors: Hermann-Dieter Schroeder, Kevin Dankert

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Germany, the CMPF partnered with the Hans Bredow Institute for Media Research at Hamburg University, which conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

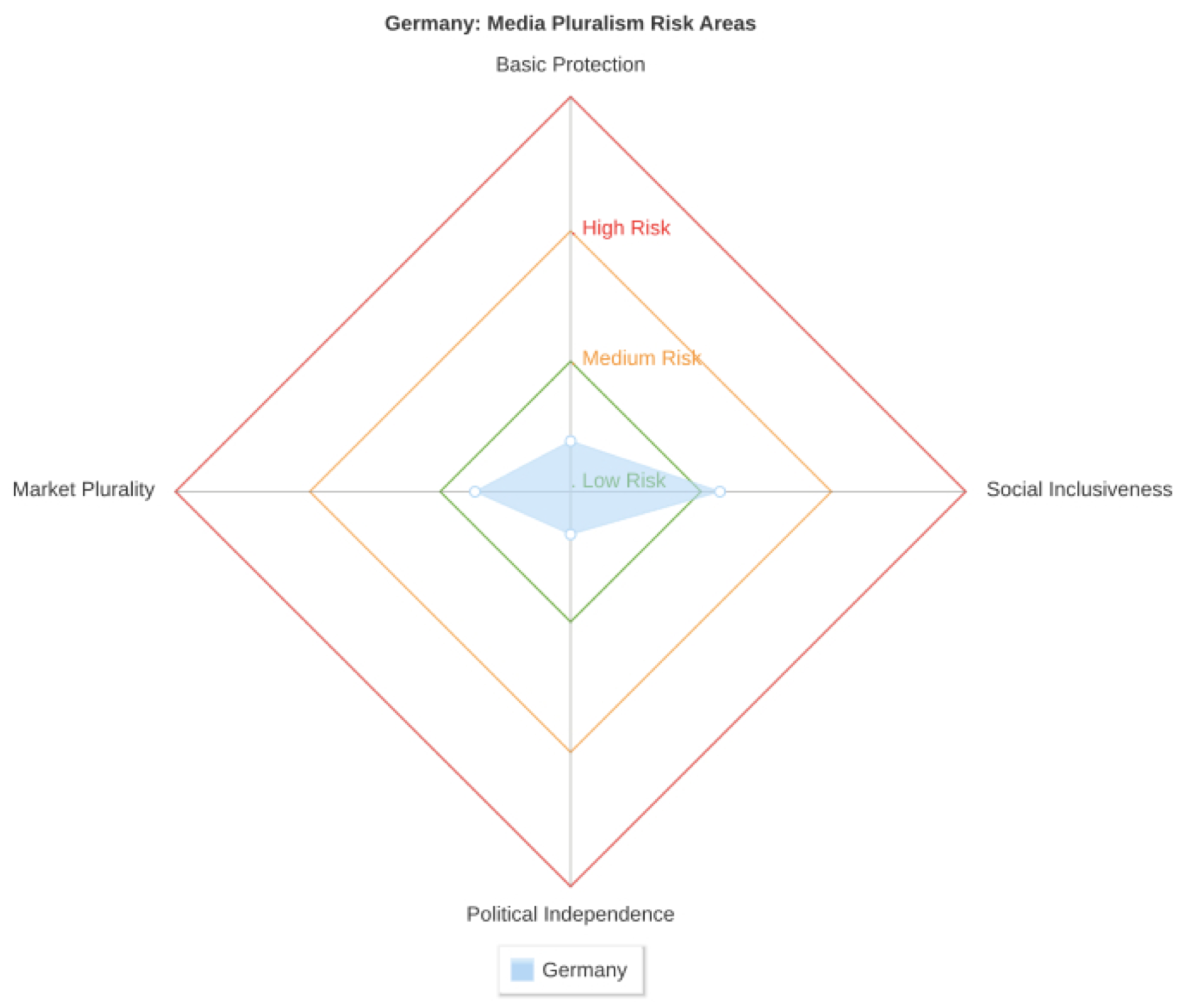

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Germany has a population of 82 million inhabitants, four million of them being citizens of other EU countries and another five million people from countries outside the EU. There are four autochthonous minorities (Sorbs, Danes, Romani people and Frisians) with approximately 240,000 members in total, that is about 0.3% of the population. The latter are represented by a Minorities Office (Minderheitensekretariat der vier autochthonen nationalen Minderheiten und Volksgruppen in Deutschland) established in 2005.

The most widely accessed media channels in Germany are television and radio. 80% of the population aged 14 years and older watch television every day and 74% listen to radio on a daily basis. The Internet is used daily by 46% of the population, and print media is consumed every day by 33%.[2] Digital satellite and cable make up the preferred modes of transmission for television content, while terrestrial, analogue services prevail for radio.[3]

The media system in Germany is determined by the constitution and the settled case law of the Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht). Media affairs are regarded as being a cultural matter that falls under the legislation of the sixteen federal states (Bundesländer). Regulation of the mass-media is, however, in part, unified by interstate treaties.

Most regulatory measures, as far as the media are concerned, focus on television, due to the perception that it is highly influential in forming public opinion. The Federal Constitutional Court and the basic law guarantee that public service media is not state controlled, and that policies exist to enhance media plurality and to limit media concentration.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Implementation of the MPM2016 indicates, in general, a low to medium risk to media pluralism in Germany. Freedom of expression and freedom of information are protected by the Constitution and the Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht). There are no restrictions to access to the journalistic profession. The German Press Council (Presserat), a self-regulatory organisation of journalist associations and print publisher associations, has established the German Press Code. The regulatory authorities, including the Federal Network Agency, the Federal Cartel Office and 14 Regional Media Authorities, are independent and effective.

The indicators for market plurality show some risks, especially regarding the horizontal media ownership in the TV market: The public broadcasters and the three largest commercial broadcasters together hold a market share of 88%. Medium risk is also found regarding the commercial and owner influence over editorial content – freedom of the press is at first freedom of the publisher, not of the employee.

The political independence indicators show medium risks regarding political control over the media outlets. Political parties have some influence in the composition of the supervising boards of the public broadcasters, and some of them are shareholders of private broadcasters and newspapers. On the other hand, there are strong restrictions on advertising in broadcasting.

In the social inclusiveness area one indicator shows high risk: Access to media for minorities. Autochthonous minorities (about 0.3% of the population) have no guarantees for access to airtime. The only groups with special access to airtime are churches and the Jewish communities.

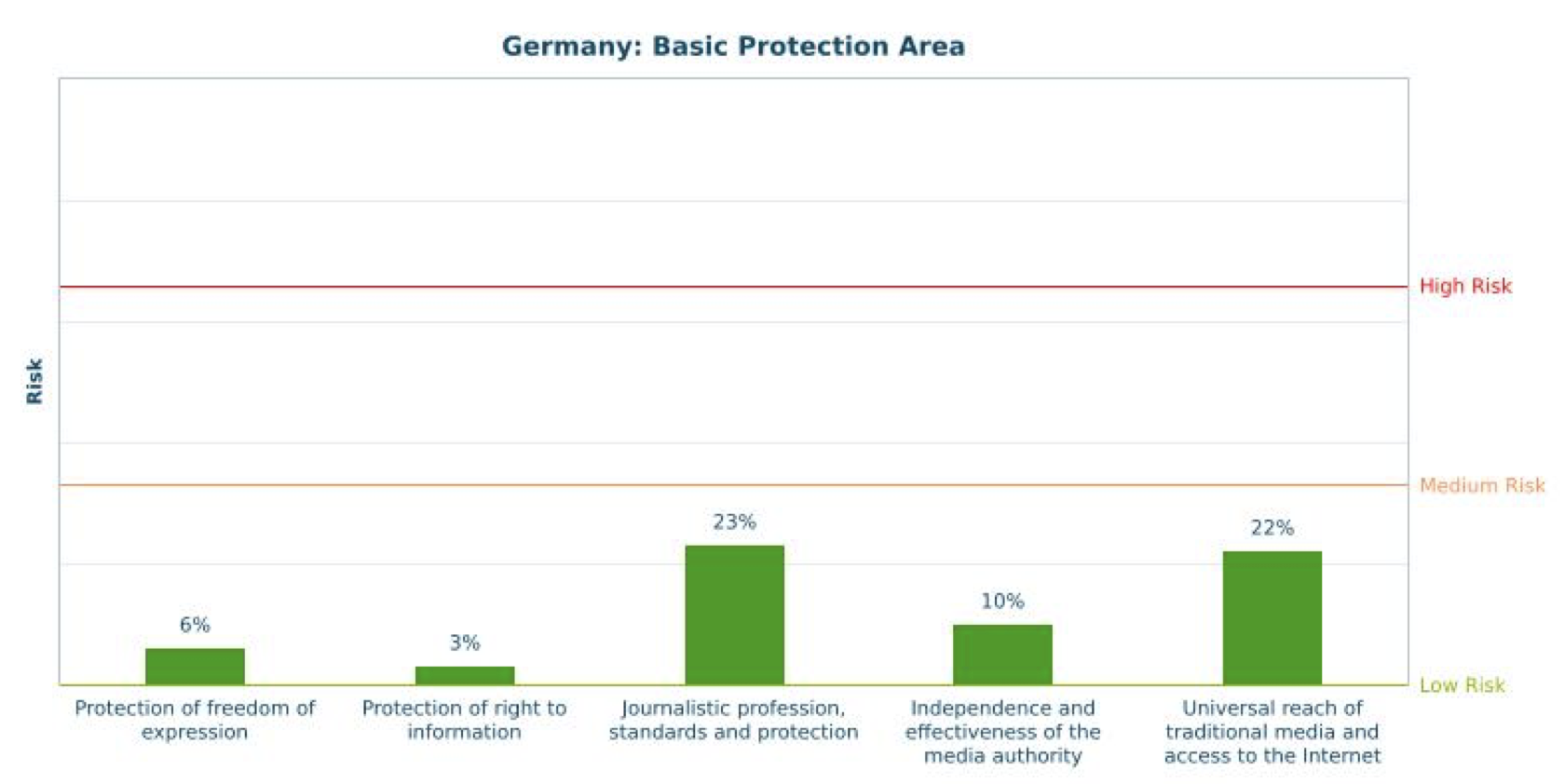

3.1. Basic Protection (13% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

For the Basic Protection area all of the indicators show very low risks to media pluralism in Germany. Freedom of expression (indicator: 6% of risk) is guaranteed by the German Constitution and by the ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and, to date, there is no evidence of any violations. Citizens have the right to a legal remedy in cases of infringements upon their freedom of expression. On the other hand, defamation is a criminal offence, thus posing some risks to freedom of expression. Furthermore, freedom of information (3% risk in the connected indicator) is protected by the constitution, by national law, and by appeal mechanisms against denials of freedom of information requests.

Risks to the Standards of journalism, and to its protection as a profession, are low (23%). There is relatively unrestricted access to information. The law guarantees the protection of sources, but news organisations must be accountable. Professional associations represent a large proportion of journalists. The German Press Council (Deutscher Presserat) is a voluntary and self-monitoring press regulator which was established by the associations of journalists and of newspaper and magazine publishers. Emphasising a commitment to the freedom of the press, the German Press Council handles complaints from the public concerning possible violations of press standards. Despite the relative independence and professionalism of the field, increasing financial pressures on publishers are degrading working conditions and threatening job security for practitioners. Occasionally, as a result of political conflict, journalists are portrayed as being dishonest and, at times, in particular during right-wing political demonstrations, they have been threatened with physical abuse.

For the Independence and effectiveness of German regulatory authorities risks are low (10%). For print media, there are no special regulatory authorities besides the German Press Council. A broad stratum of society is represented at the board level of each public broadcaster so as to ensure a certain plurality of opinion, independent of any centralised authority. The degree of separation between public media and the state is, however, constantly under review. Fourteen Regional Media Authorities (Landesmedienanstalten) externally control private broadcasters and digital services (Telemedien). These authorities have a legal guarantee of independence from political and commercial interference. Media companies are also subject to competition regulation by the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt), which is also independent. Its tasks, duties and responsibilities are defined in detail by law. The same is true for the communications regulator, the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur).

Also the risk for Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet is low (22%). The entire population is covered by signal of public radio and TV channels. The coverage of broadband is high even in rural areas, but the concentration in Internet service providers is high and the average Internet connection speed is just average.

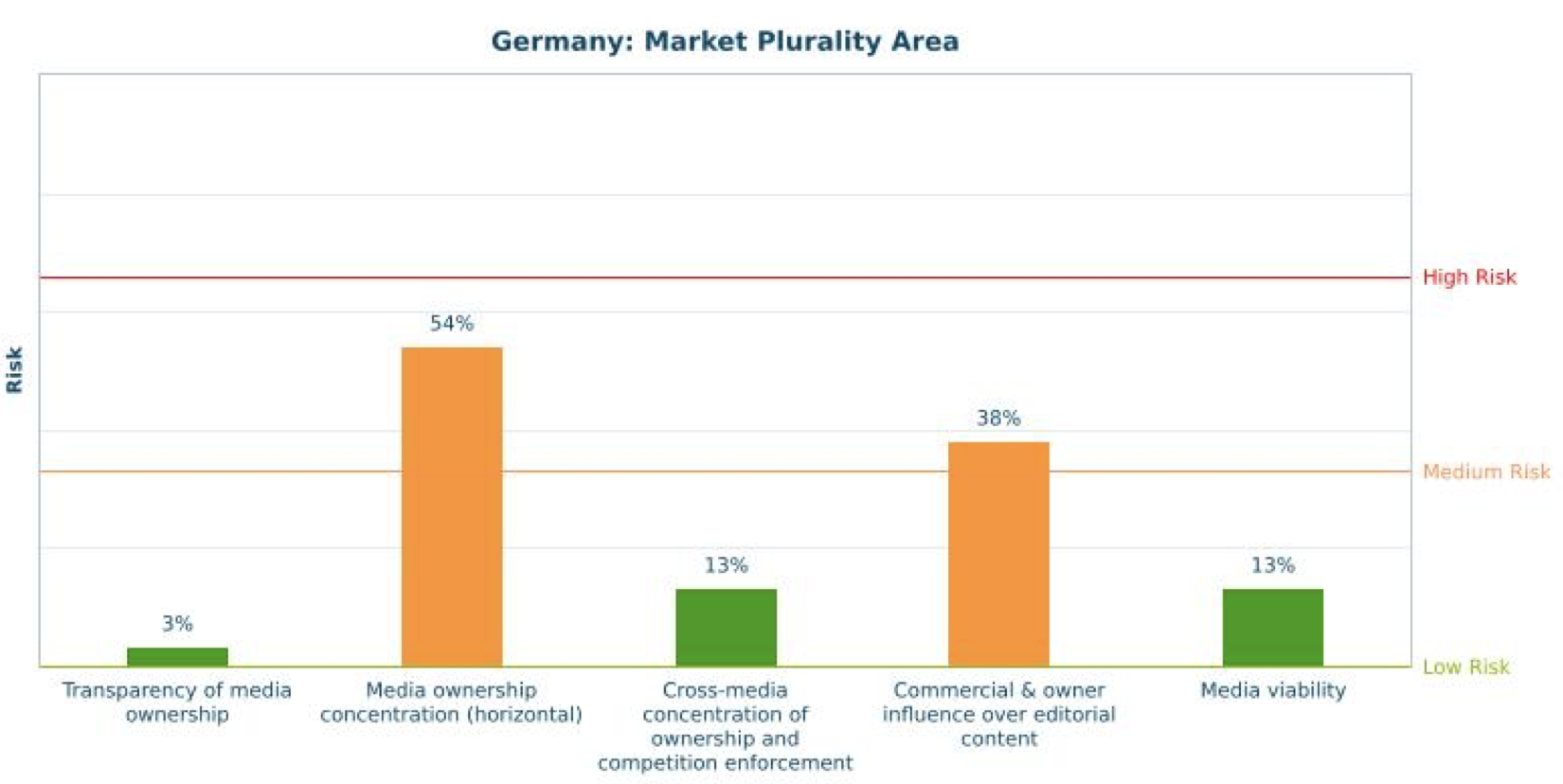

3.2. Market Plurality (24% – low risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicators for the market plurality domain lead to an ambivalent assessment. The evaluation of Transparency in media ownership shows a low risk (3%). There are no special rules that oblige media companies to publish their ownership structure to the public, but in many cases they take the legal form of incorporated companies and they are therefore obliged to publish their financial reports. Broadcasters must publish annual reports, including notes of their annual accounts; they must report ownership structures and disclose the relevant information after every change in their ownership structure.

The Horizontal media ownership concentration indicator shows a medium risk to media pluralism (54%). In order to prevent a predominating power of opinion there are normative provisions to prevent media concentration in audiovisual media, which are based on audience share. For radio, newspapers and Internet content providers there are no specific thresholds to prevent high levels of concentration. Media mergers, however, are also subject to German competition law, providing additional barriers to undesirable mergers and acquisition cases. The audience concentration of the TV market is very high. The Top4 (public broadcasters, RTL Group, ProSiebenSat.1, and Sky) achieve a market share of 88% of television viewing time. In contrast to this the Top4 newspaper publishers have a 37% share of the total circulation.

The indicator Cross-media concentration of ownership scores a low risk (13%). The German Commission on the Concentration in the Media focuses on television, but, to a limited extent, also includes other relevant markets. Thus in former decisions the acquisition of a large commercial TV company by a leading publishing house had been prohibited.

Commercial and owner influence over editorial content scores medium risk (38%). Freedom of the press in Germany at first means freedom of the publisher. On the other hand some media have an editorial charter to separate commercial and journalistic interests. Also, the German press codex and the competition law provide some regulation against mingling editorial content and advertising.

The media viability indicator scores low risk (13%). The German advertising market is growing, except for the newspapers. The license fee revenues of the public broadcasters are rising. The film industry is supported by state subsidies.

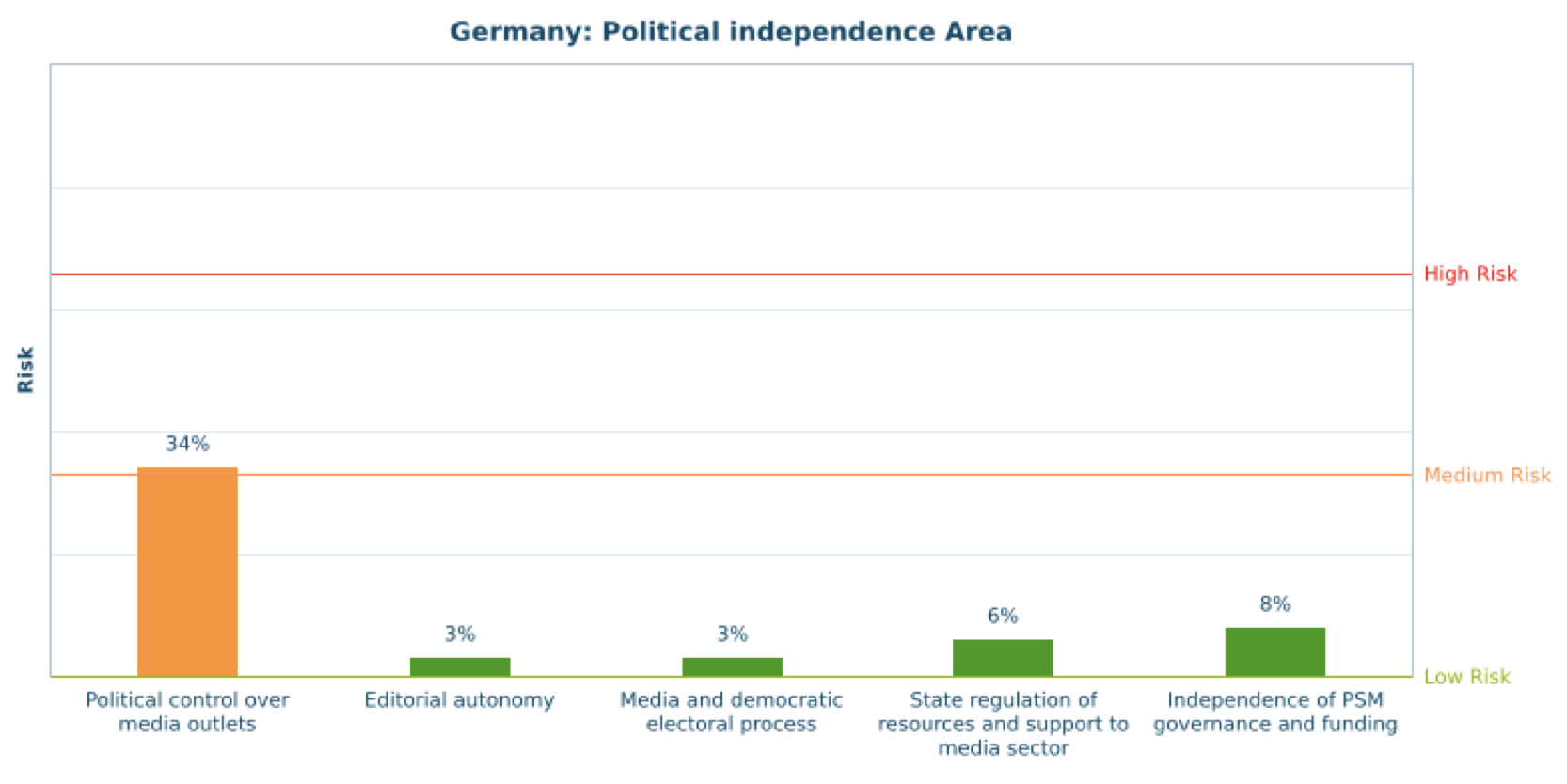

3.3. Political Independence (11% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Political control over media outlets indicates a medium risk (34%) for Germany. There is some political influence in the composition of the supervising boards. For this reason, the Federal Constitutional Court in 2014 decided that the rules for the board of ZDF, the nationwide public service TV broadcaster, must be changed. In some cases political parties, mostly the Social Democratic Party, are also shareholders of newspapers and indirect minority shareholders of private broadcasters. All political parties have to present a statement about their shares in media companies to the president of the national parliament, and these statements are published. As far as national broadcasting channels are concerned, political parties are not allowed to obtain a licence by law.

There is no evidence of risks regarding Editorial autonomy (3%) or Media and democratic electoral processes (3%). Recent research evaluating the main TV newscasts of public and commercial broadcasters did not find arbitrary decisions of specific broadcasters regarding the political information but rather common professional standards. In general political advertising in broadcasting is not allowed. But during national election campaigns, public as well as commercial broadcasters have to provide access to any party that is participating , either free or charge (public broadcasters) or charging not more than the prime costs (commercial broadcasters).

The State regulation of resources and support to the media sector shows low risk (6%) for media pluralism. Direct state subsidies are mainly granted for film production and are distributed according to fair and transparent procedures. The main indirect subsidy for all print media (except printed material primarily dedicated to advertising) is the reduced VAT rate of 7% instead of the 19%.

The Independence of public service media governance and funding in Germany is at low risk (8%). Fair, objective and transparent procedures for management and board functions guarantee independence from government or from any single political group. Wages are negotiated between the public broadcasters and the unions. The level of license fees for public broadcasters is specified by an interstate treaty of the federal states which is based on the recommendation of the commission for the determination of the financial needs of public broadcasters (KEF Kommission zur Ermittlung des Finanzbedarfs der Rundfunkanstalten).

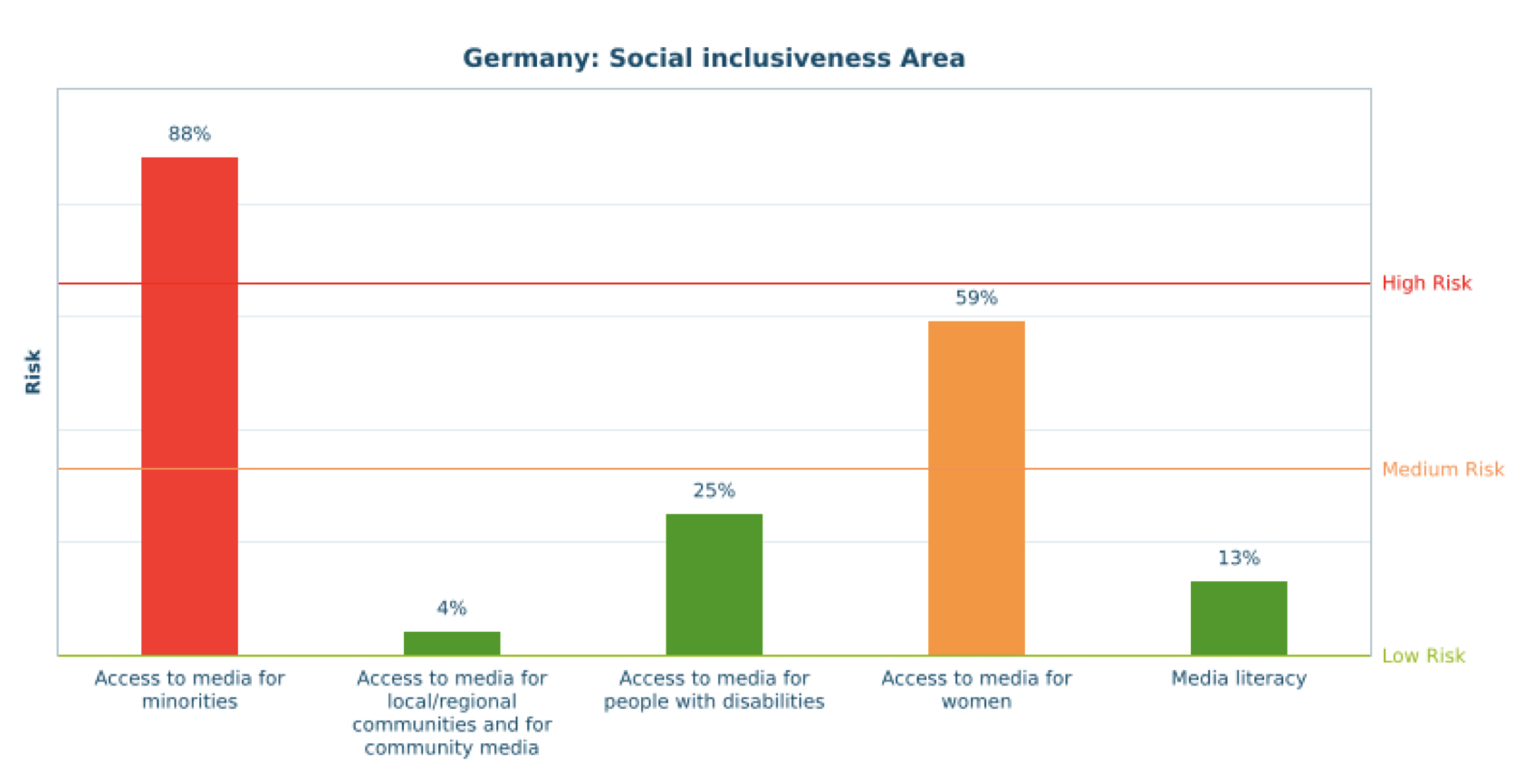

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (38% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Three of the indicators in the Social Inclusiveness area show low risk. The only indicator showing high risk is Access to media for minorities (88%) because the four autochthonous minorities in Germany that are recognised by the law[4] are very small (in total about 0.3% of the population) and they do not have a legal guarantee for access to airtime on PSM.[5] Such a guarantee exists only for churches and Jewish communities. There are no legally established special television or radio channels for minorities. However, many different groups are involved in the supervisory boards of the public service broadcasters. For instance, according to the recently amended ZDF Interstate Treaty, the ZDF television includes members representing migrants, Muslims, regional and minority languages, and sexual minorities[6].

The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores low risk (4% risk). A requirement to provide community media platforms is stipulated by law in most states as a way of enhancing plurality.

The Access to media for people with disabilities scores low risk (25%). Film subsidies are given only for productions that include audio descriptions and subtitles. The PSM have self-commitments and offer much barrier-free content.

The Access to media for women is scored as medium risk (59%). There is a General Act on Equal Treatment and the PSM have gender equality policies in place. Still in the PSM management boards, among the news reporters and in the news women are a minority.

Media literacy scores low risk (13%) and is recognised as an important issue by the federal states (and their media authorities) as well as by the federal government. They are mostly concerned with media literacy of children. In part due to federalism the policy on media literacy is not really coherent.

4. Conclusions

The protection of the pluralism of the mass media in Germany is a major achievement of media regulation and the monitoring of the legal framework by the German Constitutional Court. Recent history shows that it is essential that Germany has a Constitutional Court that can protect fundamental rights from the whims of party politics.

The results of this implementation of the Media Pluralism Monitor indicate that the main risk to media plurality in Germany is the concentration of media ownership. Media regulators and politicians have been aware of this issue for many years. It is important that the regulation of media concentration is developed further in relation to developments in Internet-based media. Media legislation still focuses on television, and it is questionable whether the old idea of television as a dominant medium can be sustained. Legislation in the field of the mass media is significantly influenced by European law, so the scope of actions at a national level is limited.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Hermann-Dieter | Schroeder | Senior Researcher | Hans Bredow Institut for Media Research, Hamburg | X |

| Kevin | Dankert | Junior Researcher | Hans Bredow Institut for Media Research, Hamburg |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Michael | Brueggemann | Professor | University of Hamburg |

| Christoph | Fiedler | Manager | VDZ – Association of German Magazine Publishers |

| Claus | Grewenig | General Manager | VPRT Association for Private Broadcasting and Telemedia |

| Andreas | Hamann | Manager | Joint management office of the media authorities |

| Katharina | Kleinen-von Koenigsloew | Professor | University of Zurich |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] B. Engel, C. Breunig: Massenkommunikation 2015: Mediennutzung im Intermediavergleich. In: Media Perspektiven 7-8/2015, pp. 313

[3] ALM-Jahrbuch 2015/2016, pp. 37, 47.

[4] Immigrants, wether naturalized or not, are not protected by specific minority rights.

[5] The pilot study in 2015 defined a threshold of 1% of the population for minorities to be taken into account for this indicator. In 2016 even the very small minorities of less than 0.1% of the population each have to be taken into account, and the indicator now asks for rules and media output dedicated to these minorities proportional to the size of the population of the minorities. Not for all small minorities there are dedicated media or programming hours.

[6] One member shall represent the field of lesbian,gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender, intersexual and queer people, cf. ZDF 2017: Fernsehratsmitglieder nach entsendenden Organisationen, https://www.zdf.de/zdfunternehmen/zdf-fernsehrat-mitglieder-entsendende-organisationen-100.html.