Czech Republic

Download the report in .pdf

English

Authors: Václav Štětka, Roman Hájek and Jana Rosenfeldová

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In the Czech Republic, the CMPF partnered with Václav Štětka, Roman Hájek and Jana Rosenfeldová Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

The Czech Republic is a Central European country with a population of 10.4 million inhabitants. According to the Government’s council for national minorities[2] The country is ethnically rather homogeneous, with a relatively marginal presence of ethnic minorities (estimated 1,5-3% of Roma people, 1,5% of Slovaks). After a period of recession in 2012-2013, the Czech economy has been recovering in the last couple of years, with GDP growing by 4.5% in 2015, more than twice as much as the EU average. The unemployment rate is around 5%, one of the lowest in the EU. There is however a very low inflation (0.3% in 2015), which is below the 2.0% target set by the Czech National Bank.[3]

The political situation has been relatively stable since the 2013 snap elections which significantly reshuffled the political map of the country and brought to power a new coalition government formed by the Social Democratic Party, the populist centre-right party ANO and the Christian Democratic Party. Despite increasing tensions and discord among the coalition members, it is widely expected that the government will serve its full term until the general elections in Autumn 2017.

The media market is characterized, among other features, by an overall dominance of television, attracting about half of the total advertising expenditures in the country. Czech Republic has a dual broadcasting system, with both public service radio (Czech Radio) and television (Czech Television) having a stable position on the market and attracting relatively high shares of audience (23% in case of Czech Radio, 30% in case of Czech Television). Also the national press agency (Czech Press Agency) has a public service statute. Daily print market is highly concentrated, with only four nationwide quality newspapers, two tabloids and a network of regional newspapers: Deník. The circulations of most of the dailies have however been declining by 5-10% every year since the 2008/2009 global financial crisis, and publishers have been affected by dwindling revenues, given the inability to generate profits from the online editions of print newspapers, most of which are accessed without payment (only a handful of online news outlets have a paywall). Online news consumption is becoming ever more important; according to the 2016 Digital News Report, the Web (including social media) is the most used platform for accessing news among Internet users (91%), followed by television (81%), radio (35%) and print (34%).

The framework for media regulation, whose main contours have been set up during the 1990s (following a neo-liberal approach to the role of the state) and then harmonized with the EU framework during the accession process, has not gone through any major changes since then. A notable exception has been an amendment to the Act on the Conflict of Interest, explicitly prohibiting politicians from owning stakes in media, which was passed through Parliament in November 2016.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

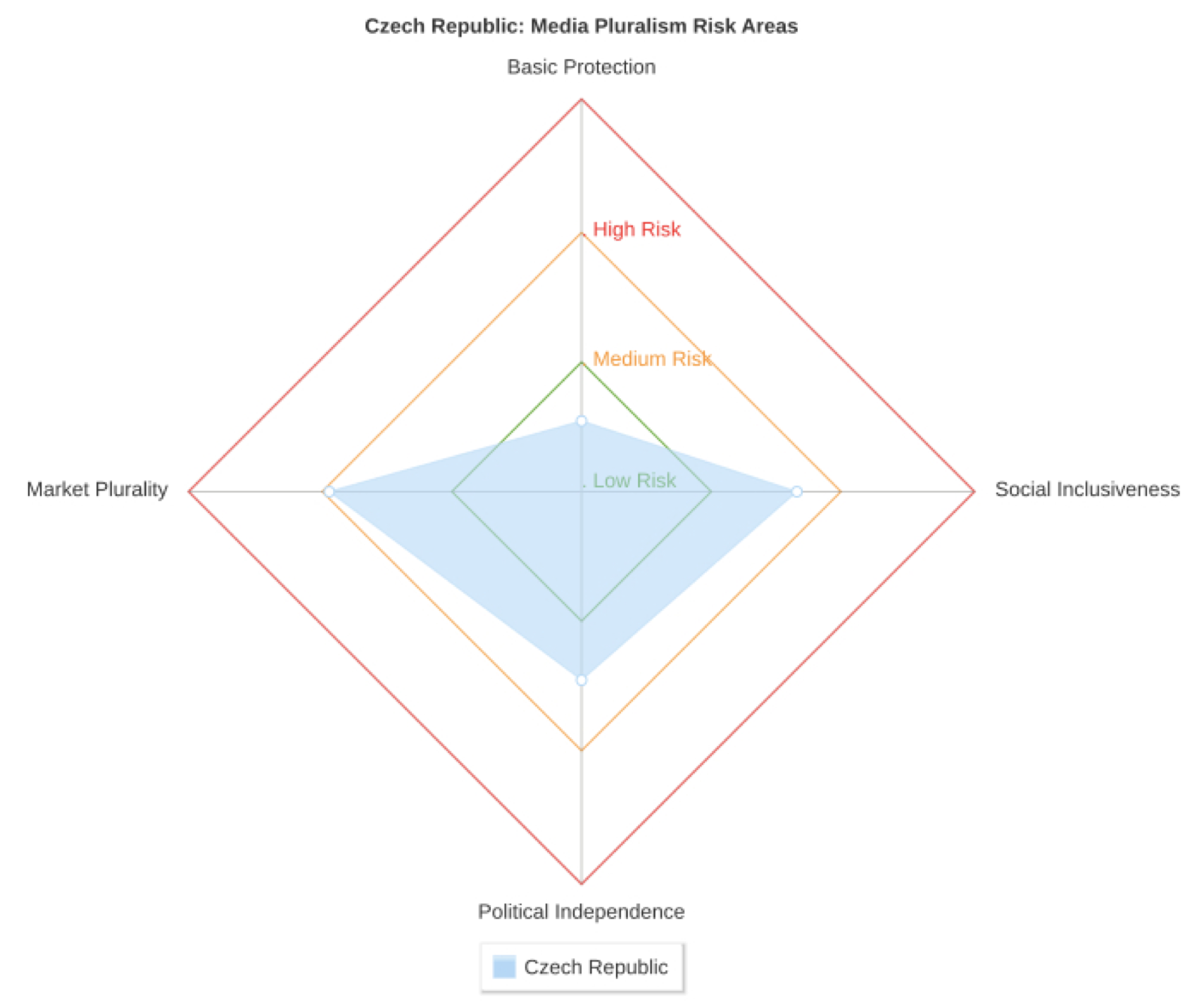

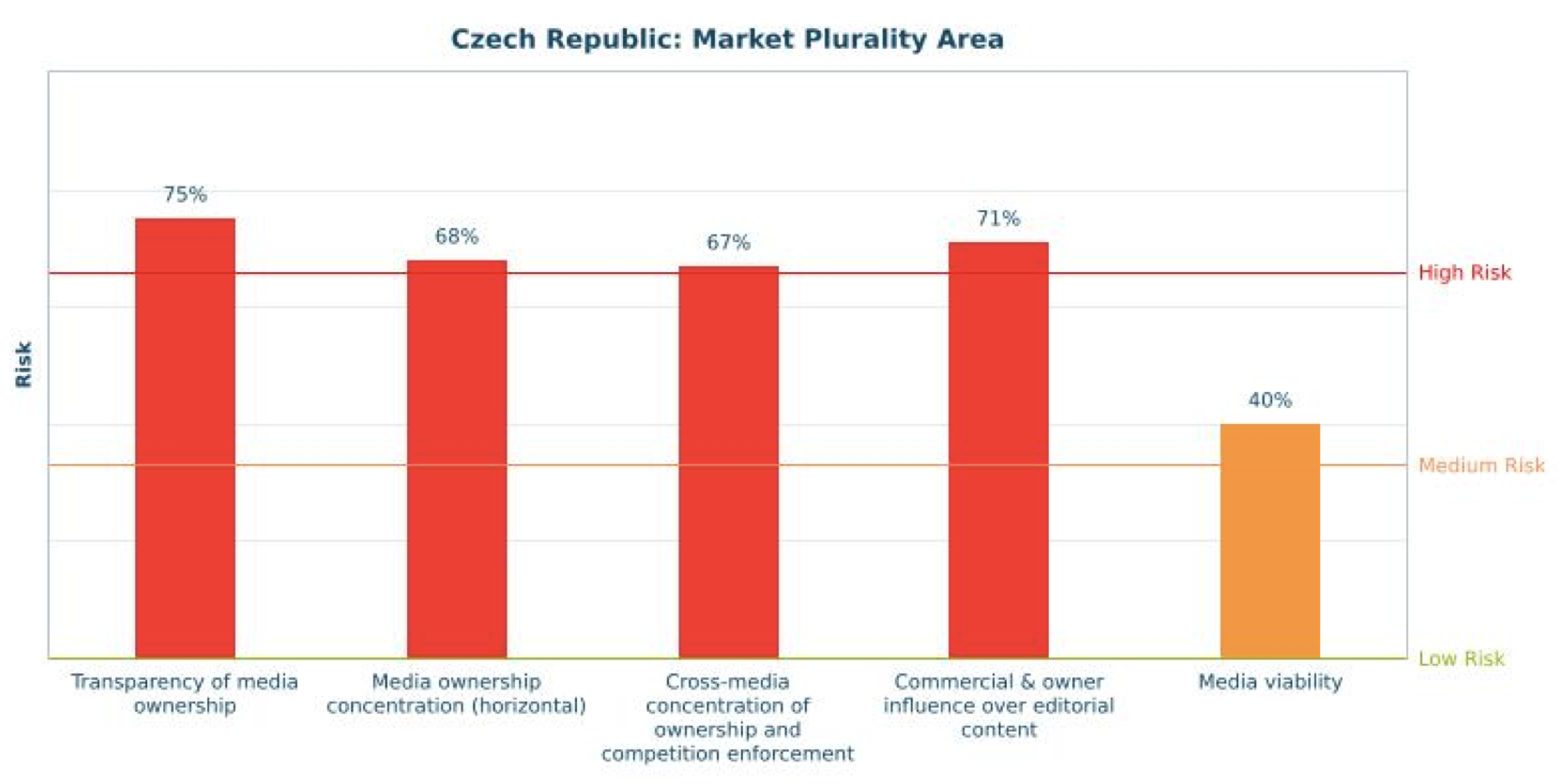

The implementation of the MPM2016 for the Czech Republic shows medium risk for media pluralism in three out of four areas; only one area (Basic Protection) displays low level of risk. While Social Inclusiveness and Political Independence areas scored towards the middle of the medium risk category, Market Plurality is on the verge of high risk level, with four out of five indicators being above the high risk threshold – in particular, Transparency of media ownership (75%), Media ownership concentration (horizontal) (68%), Cross-media ownership concentration (67%) and the Commercial and owner influence over editorial content (71%). These results clearly demonstrate that protecting market plurality and safeguarding editorial autonomy vis-à-vis commercial and ownership pressures are currently among the most pressing challenges for media pluralism in the Czech Republic.

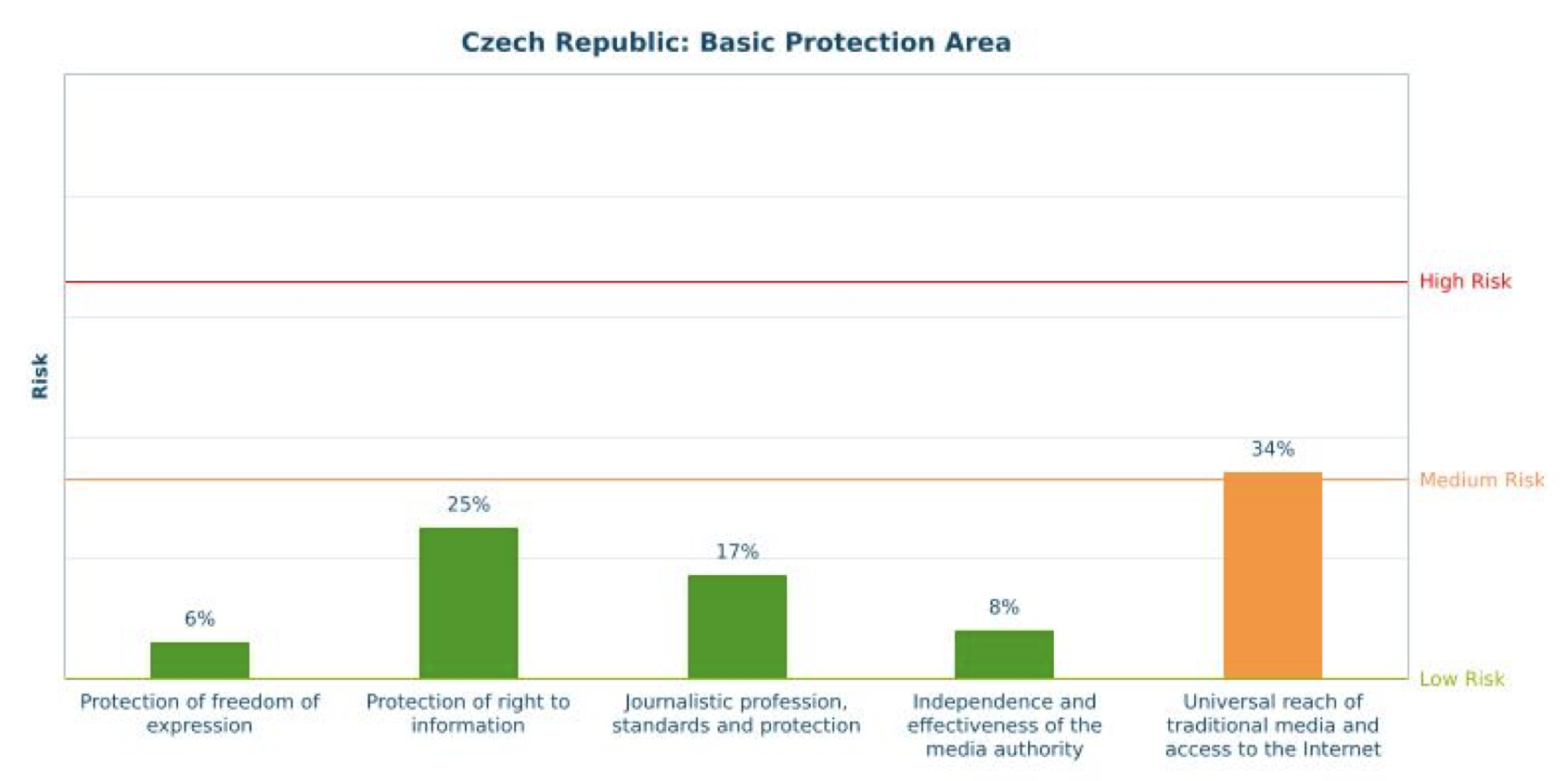

In the Basic Protection area, four out of five indicators scored low risk; the only that has (narrowly) exceeded the medium threshold was Universal reach of traditional media and internet access (34% risk), mainly due to the gaps in broadband connectivity in rural areas (91%) and also because of the relatively low rate of broadband subscription (71%).

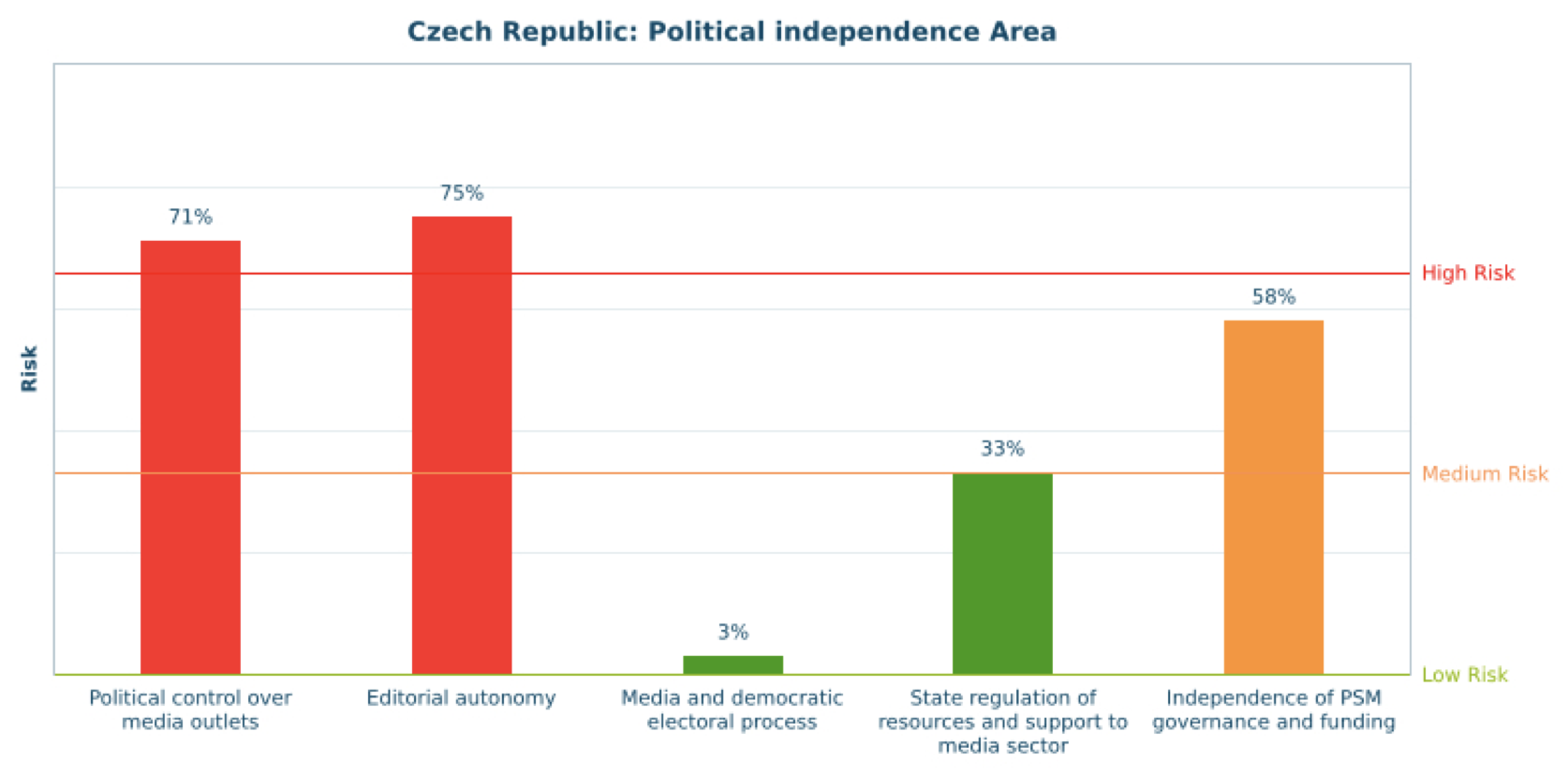

The indicators in the Political Independence area ranged from low risk (Media and democratic electoral process, 3% and State regulation of resources and support to media sector, 33%) to medium (Independence of PSM governance and funding, 58%) to high (Political control over media outlets, 71%, and Editorial autonomy, 75%). This indicates that while on average the risk for media plurality originating from political actors is assessed as medium, there are some high-risk instances of undue political control and intervention, mostly related to the current Deputy Prime Minister Andrej Babiš who belongs to the most influential media owners in the country.

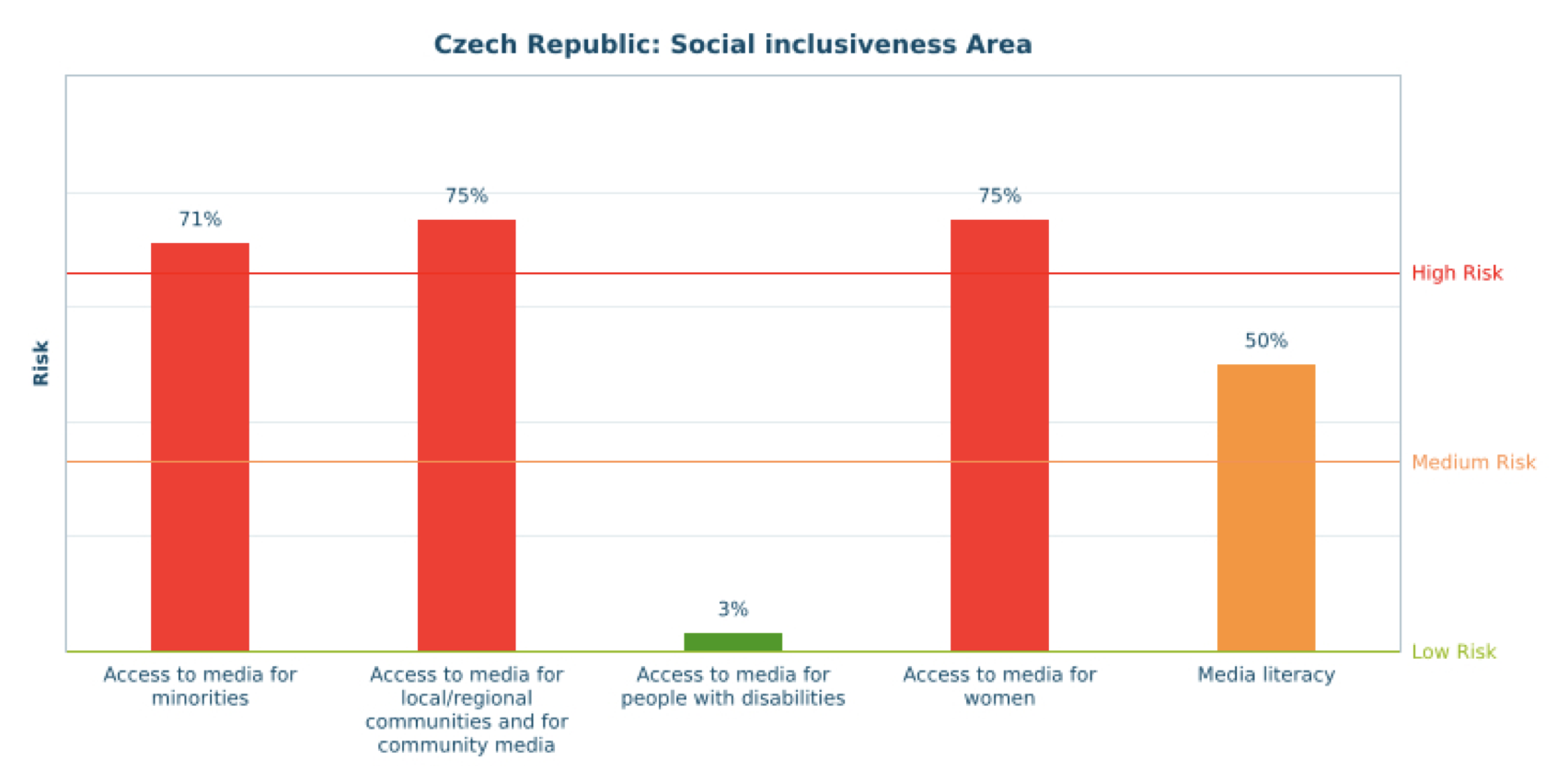

Finally, the Social Inclusiveness area as a whole displays medium risk (55%). However, the medium risk score somehow obscures the fact that three out of five indicators scored high risk levels, largely because of the missing legal safeguards of airtime access for minorities, the absence of legal safeguards for community media, as well as lack of PSM gender equality policy and persisting gender gaps when it comes to holding managerial positions in the media.

3.1. Basic Protection (18% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The Czech law on freedom of expression meets the international human rights standards (6% score in the indicator Protection of freedom of expression). Freedom of expression is explicitly recognised in the law, the restrictions upon this right are clearly defined, and legal remedies in case of violation of this right are effective. Despite some experts’ criticism, defamation is still defined as a criminal offense; yet actual accusations of defamation are rather rare.

The legislation also recognises the right to information; this right is included in the Czech constitution and is further specified by special law that also guarantees access to information from state authorities, territorial self-governing entities, and public institutions. This law also defines appeal mechanisms in case of denials to access information. However, the appeal mechanisms may be sometimes delayed and are not always effective (e.g. the offices tend to charge unjustified payments for providing the information and thus prevent the access to information; such cases are usually decided by courts). With occasional violations against the right to information (several offices that had previously refused to publish the information on salaries of state officers), Czech Republic scores 25% in the indicator Protection of right to information.

Aside from an increased job insecurity resulting from the recent ownership changes and from financial difficulties of many print media, suffering from declining profits, the working conditions of Czech journalists are relatively good. Although journalists are often publicly criticised and disparaged, even by the highest public authorities (including the Czech President Miloš Zeman), neither physical attacks nor online threats have been recorded lately. Thus, the major weakness of the journalistic profession in the country stems from the ineffectiveness of its professional organization. The share of journalists represented by professional associations and organizations is almost negligible (below 10% according to recent data). The leading professional association – the Czech Syndicate of Journalists – is very weak and generally not respected by the majority of Czech journalists. Its effectiveness in guaranteeing editorial independence and respect for professional standards is further undermined by the fact that the Syndicates’ Ethical Committee has no sanctioning powers. Despite these issues, the overall score in the indicator Journalistic profession, standards and protection is still within the low risk range (17%).

There is also low risk regarding the indicator Independence and effectiveness of the media authority (overall score 8%). The only media authority that has regulatory competences in the Czech Republic is the Council for Radio and Television broadcasting. Appointment procedures to this Council are clearly defined in the law, and so are the tasks and responsibilities as well as the appeal mechanisms. In recent years there has been no attempts of the government to intervene into Council’s competences; also the Council’s budget covers adequately all its needs. Nevertheless, two particular variables within this indicator scored medium risk, namely the appointment procedures to the broadcasting councils (which are sometimes not effective in safeguarding political independence of the members), and the appeal mechanisms to the decisions of the councils, which are occasionally delayed.

Finally, the indicator Universal reach of traditional media and the internet scores medium risk (34%). This is mostly caused by to the gaps in broadband coverage of the rural areas (91%) and also because of the relatively low rate of broadband subscription (71%).

3.2. Market Plurality (64% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator Transparency of media ownership scores a high risk (75%). Although media companies are not obliged to publish their ownership structures or its changes on their website, the law demands facts to be recorded in the public registers (especially in the commercial register) which are accessible to the public. However, there is no duty to reveal the “end owner” of the company. Regarding the obligations to report ownership structures of media companies to public authorities, the regulatory safeguards apply to the broadcasting sector, not to the print media sector (publishers are not required to reveal their ownership structure). Nevertheless, despite the fact that the current Czech legislation is relatively lenient concerning the obligation to disclose ownership structures of media companies, especially in the print media sector – which is why the indicator is in a high risk area – the current owners of majority of relevant Czech media do not attempt to hide behind a chain of offshore companies and are generally known to the public.

Media ownership concentration represents a high risk to pluralism of the Czech media landscape (68% risk for the horizontal concentration). The Broadcasting Act sets some limits to concentration by prohibiting a single legal/natural person from holding more than one licence for nation-wide analogue broadcasting and more than two licences for nation-wide digital broadcasting, and restricting the number of licences for local and regional television and radio broadcasting. However, there are no specific provisions when it comes to the internet and newspapers, which are thus only subject to general restrictions by the competition law.

Data on ownership concentration, measured by audience/readership shares (publicly available figures on revenues are incomplete) indicate a high level of horizontal concentration. The audience share of the Top 4 owners in the television sector accounts for 88%; the nation-wide radio market is divided among three players, and the entire nation-wide newspaper sector belongs to only four owners. The excessive horizontal concentration is most evident in case of the Czech regional print media market, where the daily Deník, with its 72 regional mutations, enjoys a monopoly position, enabled by the traditionally very inclusive definition of the “relevant market” by the competition authority.

The results for Cross-media ownership concentration and competition enforcement show similar level of high risk (67%). There are no specific thresholds to prevent a cross-ownership between the different types of media. None of the Broadcasting Act, the Press Act or the Act on the Protection of Competition contains any limits on cross-media ownership. The decisions of the Office for the Protection of Competition always depend on the definition of the “relevant market” which allows for high degree of flexibility in interpretation. The unavailability of certain figures (e.g. market share of the Top4 owners across the different media sectors) also contributes to the high level of risk for this indicator.

The Commercial & owner influence over editorial content indicator scores even higher (71%). There are no specific mechanisms (legal or self-regulatory) granting social protection to journalists in case of the changes of ownership or editorial line, no laws prohibiting advertorials or stipulating the obligation of journalists/media outlets not to be influenced by commercial interests. However, some media deal with this issue as part of their editorial codes.

There have been some dramatic changes in the Czech media ownership over the last three years leading to the entry of Czech business tycoons into the media market. This process of „oligarchization“ of Czech media has led to frequent discussions on the motivations of these new media owners, many of whom are widely believed to use news outlets to further their own economic and political interest.

As for the last indicator, Media viability (medium risk, 40%), there are no aggregate data for the development of revenues of individual sectors as a whole. Based on the advertising investments and the development of revenues by some of the biggest players we estimate that revenues of the audiovisual and radio sector have increased over the past two years, while data for the newspaper publishing sector shows a decrease in revenues.

3.3. Political Independence (48% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The indicators for the Political Independence area range from low to high risk to media pluralism. Although many legislative regulations and practices serve to guarantee media independence from political pressures, there are some areas where such guarantees are found wanting.

Political control over media outlets is a high risk indicator with an overall score of 71%. Despite the ongoing discussions and a recent legislative attempt by the Parliament, by the end of 2016 Czech law does not regulate conflict of interests between owners of media and politicians. The most obvious and publicly discussed conflict of interest is currently the case of the Deputy Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, whose company Agrofert owns several significant Czech media (two quality newspapers, radio station with the largest audience share, music TV channel, etc.). The high risk score of this indicator does not, however, necessarily mean that there is an excessive politicization of control over media outlets – the share of TV channels owned by politically affiliated entities accounts for 0,7%, 12% for radio channels and 32,5% for national newspapers (all measured by audience/readership shares). The particular risk-increasing factor is the lack of self-regulatory mechanisms that would stipulate editorial independence.

The high risk for the indicator Editorial autonomy (75%) stems mainly from the absence of legal regulation ensuring autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief. In general, there is no evidence of systematic external political interference when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief of Czech news media. However, there is the specific case of media owned by Andrej Babiš, the Deputy Prime Minister and Leader of the ANO party, who is believed to exert influence over his newspapers’ editorial content. According to the Freedom of the Press 2015 report, some degree of self-censorship is present among Czech media workers, particularly at outlets whose owners have significant links with business or politics.

Election laws regulate the fair access to airtime during election campaigns and there is little evidence of complaints against the broadcast media conduct during electoral campaigns. Buying of political advertisements is prohibited. Apart from occasional incidents, Czech broadcasters generally fulfil their legal obligations. Therefore, the indicator Media and democratic electoral process displays an overall low risk (3%).

Regarding State regulation of resources and support to the media sector (33%), the variables within this indicator score low to medium risk. The elevated risk is caused by two main factors: firstly, by the absence of fair and transparent rules for the distribution of direct subsidies to media outlets; secondly, by the lack of rules on distribution of state advertising to media outlets. There are no publicly available data for the amount of state advertising. This in itself constitutes a problem, because the distribution of state advertising can be used as an instrument of economic pressure on media, especially in times when profits of commercial media companies are falling.

PSM governance and funding is considered as medium risk (58%). Although the members of the broadcasting councils of both Czech television and Czech radio are nominated by civil society and cannot be active in political movements, the final appointment depends on the political majority in the Chamber of Deputies and therefore, despite the stipulations of representation of a variety of interests, the appointment procedure lacks proper safeguards and remains vulnerable to political influence. The main source of funding for PSM in the Czech Republic comes from fees defined by law which can only be amended by the Parliament. The fees are enumerated in the law and do not depend on other economic indicators. Since the fees constitute the main source of income for both the television and the radio, political influences cannot be fully eliminated, as the change in fees requires legislative action by the Parliament.

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (55% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The Czech Republic is nationally and ethnically relatively homogeneous, so in the last couple of decades there have not been too many pressures on media policy development in the area of access to media for minorities. The indicator on Access to media for minorities scores high risk (71%). There are no clear legal guarantees of access to airtime for minorities. In the case of PSM channels, the law imposes to offer programmes targeted at (ethnic and national) minorities, but without further specification (e.g. of the amount of airtime). There is a lack of data about the proportionality of minorities’ access to the media. The Czech media system does not have any significant minority medium: there are no daily newspaper, no TV channel and only units of radio channels dedicated to minorities (quite understandably because the potential audience is small).

For the indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media, the situation is very similar – a high risk score (75%). The Czech media system is highly centralised, which is especially the case of newspaper and TV market. Regional and local media are not defined specifically by the law and they are not systematically supported. In the broadcasting market, no specific frequencies are reserved for regional/local media. As a result, the market shares of local/regional media are small or even marginal (in case of TV). Radio may stand as an exception since regional/local broadcasters gain over 50% market share but it should be noted that these are mostly music stations with only limited space for local/regional news. The high risk score for this indicator is further caused by the absence of community media guarantees in the legislation. There are some media outlets that meet the definition of community media (mostly radio stations), but there is no legal definition, protection, neither systemic support of such media. There has been an expert debate in recent years about this topic and the Ministry of Culture aimed in 2013 to involve community media as the “third pillar” of the Czech media system. However, it has not been done so far and at the moment it does not seem to be on political agenda.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scores low risk (3%). There is a well-developed policy that requires both PSM and commercial media (the latter to lower extent) to allow access of people with disabilities to media content. In practice, in most cases media surpass the quota set by law.

In the following indicator, Access to media for women, the overall score shows high risk (75%). Although there is a general equal rights law which is applied quite effectively, the actual presence of women in the media is limited only to particular (and lower) working positions. Only a small percentage of Czech women hold a managerial position, as a case in point, only 17% are women on the PSM management board.. The lack of data on women in the media, combined with the absence of gender policy in the media, suggests that gender issues are not considered to be important in the media.

The indicator Media literacy scores medium risk (50%). While media education is part of the educational curricula since 2006 (as an optional module), there is no specific “media literacy policy” in the Czech Republic at the moment. Most activities falling within the concept of media literacy are currently being undertaken by non-government organizations, and they are mostly limited to the area of formal education (EAO, 2016)[4]. Moreover, there is lack of systematic education of teachers and trainers in media education, underdeveloped didactic materials and an outdated conception, which does not reflect the current technological progress.

4. Conclusions

The results of the MPM2016 point to several areas where specific policy measures should be adopted in order to foster and better safeguard media pluralism. In the area of market plurality, there is a clear need for laws setting limits on cross-media ownership concentration, as the current absence of any such regulations benefits the largest players and stimulates the intensification of the process of conglomeration.

In light of the recent ownership changes which brought actors with explicit political interests into the media business, there is an urgency in establishing limits on political ownership of the media, in order to prevent from excessive politicization of the news media scene which could jeopardize journalistic autonomy. This issue has been tackled by the new amendment to the Act on the Conflict of Interest, passed by the Parliament in November 2016, explicitly prohibiting public officials to own print, radio and television media; the practical impacts of this new law are yet to be seen.

A reform of the system of appointment of the members of broadcasting councils, which are currently selected by the Parliament and therefore are closely dependent on political parties, represents another palpable issue which should be targeted by media policy. Even though many attempts at de-politicization of the councils have failed in the past, the need to safeguard greater political independence of public service broadcasters is still highly topical.

The distribution of state advertising (both via the Ministries’ public relations budgets as well as through state-controlled companies) should be made more transparent, as currently it is nearly impossible for the public to know which media are benefiting from this form of indirect state support.

Community media should be recognized by law in order to help establishing community media sector as a “third pillar” of the Czech media system, particularly given the fact that the Czech Republic remains one of the few EU countries where such sector is legally still non-existent. Also, the notion of “minority media” should be significantly broadened, as currently the only type of minority media eligible for state support is the one related to ethnic minorities.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Václav | Štětka | Lecturer

Researcher |

Department of Social Studies, Loughborough University

Institute of Sociological Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague |

X |

| Roman | Hájek | PhD student | Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague | |

| Jana | Rosenfeldová | PhD student | Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague | |

| Jan | Švelch | PhD student | Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Milan | Šmíd | Emeritus professor | Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague |

| Tomáš | Tkačík | President | Association of Czech Publishers |

| Martina | Vojtěchovská | Lecturer | Metropolitan University in Prague |

| Helena | Chaloupková | Lecturer | College of International and Public Relations |

| Adam | Černý | Chair | Czech Syndicate of Journalists |

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[3] Czech Statistical Office: https://www.czso.cz/