Croatia

Download the report in .pdf

English – Croatian

Authors: Paško Bilić, Antonija Petričušić, Ivan Balabanić, Valentina Vučković

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM carried out in 2016, under a project financed by a preparatory action of the European Parliament. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF partners with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Croatia, the CMPF cooperated with Paško Bilić, Antonija Petričušić, Ivan Balabanić and Valentina Vučković, who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Croatian team have organized a stakeholder meeting, on 14 December in Zagreb. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

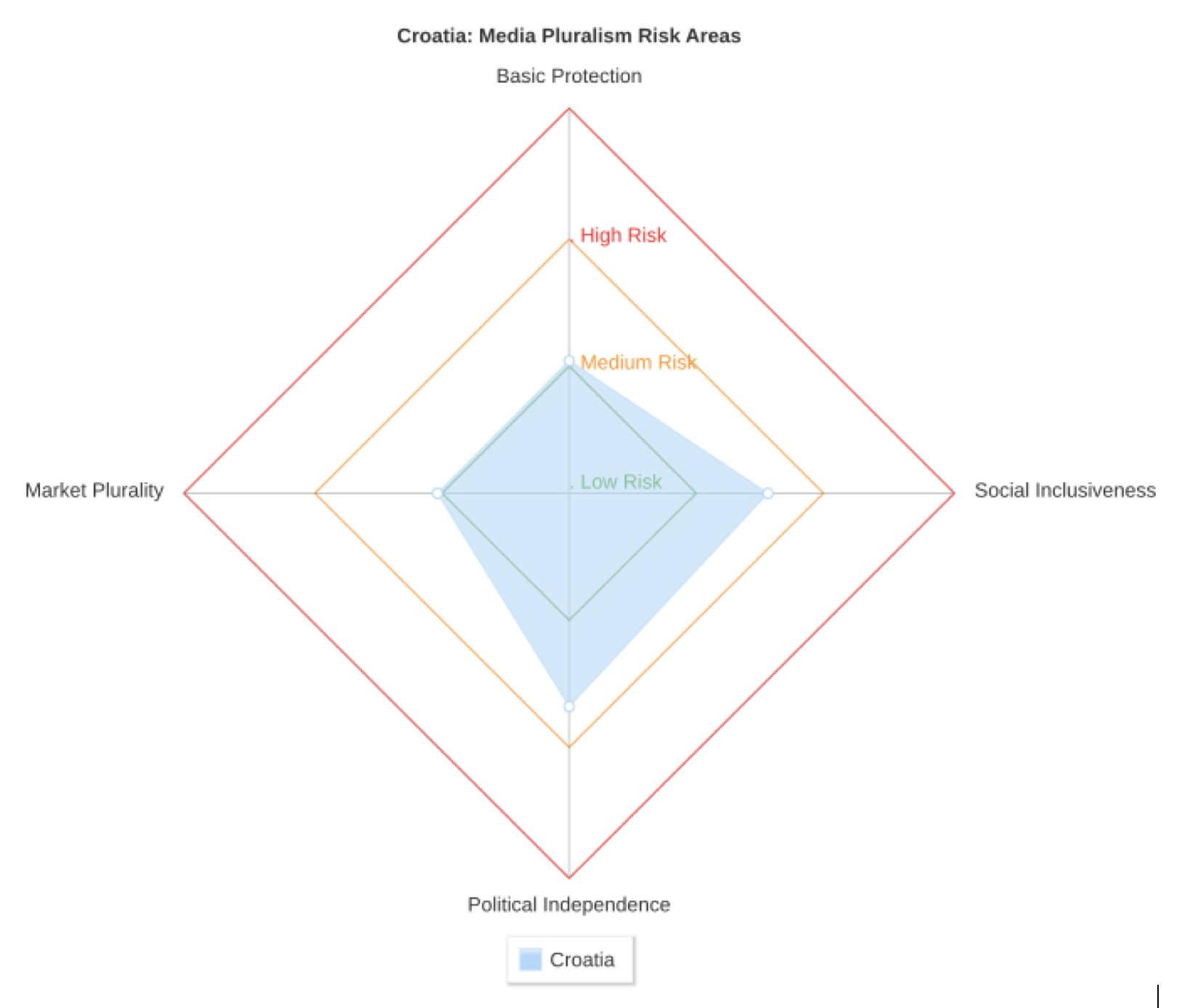

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Croatia is a country of approximately 4.3 million inhabitants situated between Central Europe, the Mediterranean and Southeast Europe. The main spoken language is Croatian. Croatia is an ethnically homogenous country with Croats making up more than 90% of the population. The main ethnic minority is Serbian with 4.4% , followed by Bosnian (0.73%), Italian (0.42%), Albanian (0.41%), Roma (0.40%), and Hungarian (0.33%).

In 2015 there were first signs of an economic recovery from a six year recession. The country still remains troubled by projections of low GDP growth rates, high public debt, unemployment, and weak public administration.

Traditionally, the majority of Croatian citizens predominantly vote for the centre-right Croatian Democratic Union, or for the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP). Recent years have seen fragmentation in the political spectrum with a rise of new parties promoting centrist approaches or radical and populist policies. The government led by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the Bridge of Independent Lists (MOST) established a parliamentary majority in January 2016. They installed a non-partisan Croatian-Canadian businessman as the prime minister and two deputy prime ministers, one from each of the major parties. The government was marked by continued tensions between the main parties in power and the rise of right-wing and conservative rhetoric by the HDZ. They culminated in the preparations for the vote of no confidence in the HDZ deputy prime minister. After the Committee on the Conflict of Interest found the deputy prime minister to be in breach, he resigned. The collapse of the government led to new parliamentary elections in September 2016. In preparation for the elections, HDZ elected a new party president and took on a reformed centre-right and pro-European position. The majority of votes went to the HDZ which again formed the parliamentary majority with MOST.

Regarding media consumption, in 2014 television was the medium of choice used by 83% of the population watching it on a TV set, followed by the internet (52%), radio (50%) and print (29%) (Eurobarometer, 2014). 20% of the population chooses to watch television online. Level of internet access in households rose from 41.5% in 2007 to 77% in 2016 but still remains below the EU-28 average (Eurostat, 2016). The percentage of population covered by broadband is 97.6% (87.2% of the rural population). The percentage of broadband subscription is 62% (Eurostat, 2014).

There have been no major legal changes in the media sector during the short tenure of the government in place between January and September 2016. However, there were social and political pressures towards the media regulator and an unfavourable policy towards the community, minority and non-profit media. The Council for Electronic Media found its annual report dismissed by the government. The newly appointed Minister of Culture disbanded the non-profit media committee and cut down all funds and public subsidies that were supporting the non-profit media sector. Most non-profit, and some minority media, found themselves in financial difficulties and on the edge of existence.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The risks to media pluralism in Croatia in 2016 are the results of short-term political instabilities and long-term economic and socio-historical processes. As a country that joined the EU in 2013, Croatia made efforts to change the legislative system and ensure that Basic Protection of media pluralism is aligned with international standards of freedom of expression and right to information. Political pressures towards the media regulator have been increasing recently. It remains to be seen whether this will represent a trend, or a one-time event. Hurdles remain in ensuring the widest possible reach for internet services and internet access in the general population, as well as to ensure better protection of journalistic standards. The working conditions and safety of journalists have deteriorated.

As a small media market Croatia is vulnerable regarding the Market Plurality. Horizontal and cross-media ownership concentration should be better regulated and a single media register established. There are risks of commercial and owner influence over editorial content which is poorly regulated. Political Independence and political control over media outlets are some of the most problematic areas in the Croatian media system. State regulation of resources and state support to the media sector remain somewhat problematic. There have been major cuts in available public subsidies for non-profit and minority media. A salient issue is the lack of safeguards for political independence. The PSM is particularly vulnerable towards shifts in the parliamentary majority. In 2016 there have been multiple cases of openly politicized appointments and dismissals in the PSM following parliamentary elections.

In the Social Inclusiveness domain all indicators show medium to high risk. Access to media for minorities, local/regional communities, community media, people with disabilities and women remain areas with much room for improvement. Finally, although slowly entering policy debates and strategic documents, media literacy remains an underdeveloped area.

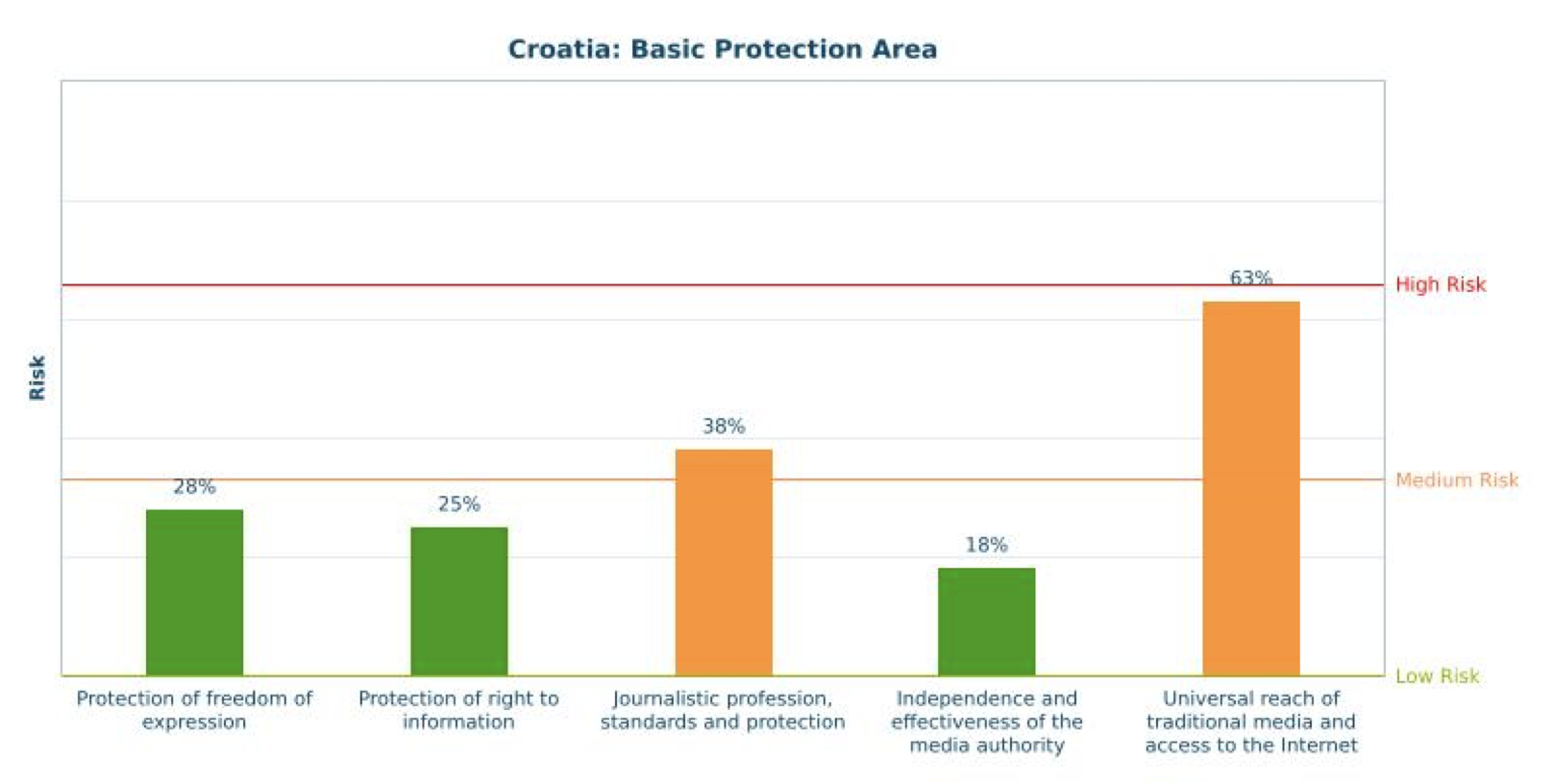

3.1. Basic Protection (34% – medium risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The protection of freedom of expression in Croatia follows basic international standards although there are some concerning issues in legislation and implementation. The state has not decriminalized defamation. Court decisions on damages are not always proportionate to the offences committed and can sometimes have a chilling effect on journalistic output. Overall, the Protection of freedom of expression indicator scores a low risk of 28%.

The protection of right to information is recognised in the Constitution and national laws. Restrictions on grounds of privacy are defined in accordance with international standards. Appeal mechanisms for denial of access are in place although they are not entirely effective. Some violations on information access occur, particularly with regard to local and regional government, trade associations, and legal entities with public authority. A general trend is a widespread disregard for respecting the legally defined and timely delivery of requested information. However, the Protection of right to information indicator shows no major issues of contention and scores a low risk of 25%.

Access to the journalistic profession is guaranteed by law and open in practice. The Croatian Journalists’ Association (HND) publicly and actively promotes professional values. Yet, it is considered ineffective in guaranteeing editorial independence. The protection of journalists is also problematic, as attacks and threats continuously occur. Examples include threats, verbal and physical attacks on major columnists and the president of the HND. The working conditions for journalists have consistently been deteriorating over recent years, especially due to the economic crisis. Overall, the Journalistic profession, standards and protection indicator scores a medium risk of 38%.

The appointment procedures to the media authority are designed to minimize the risk of political and commercial influence through the Prevention of Conflict of Interest Act. The procedures are not always effective as they are only put in place after the government appointment takes place. Tasks and responsibilities, sanctioning powers and appeal mechanisms of the authority are defined in detail in law. Appeal mechanisms seem to be effective and are not misused to delay the enforcement of remedies. There has been an increase in political pressure towards the Council of Electronic Media (VEM) after an issue of a ban on the regional television broadcaster for repeated incitement to ethnic hatred in their talk show program. The newly appointed Minister of Culture and the Croatian Government rejected the 2014 annual report by the Council and proposed to the Croatian Parliament for the Council to be removed and replaced. Due to increasing pressure the president of the VEM offered her resignation. The tensions seem to have waned due to the instability and fall of the government. The Council is still not dismissed and the President remained in office. There was a period of intense political pressure which can damage the independent decision making practice of the authority as well as the appointment and dismissal procedures in the future. The budgetary resources for the authority are transparent, objective and adequate. The authority is transparent and regularly publishes information about its activities. The Independence and effectiveness of the media authority indicator scores a low risk of 18% but should be closely monitored in the future due to open political pressures that occurred.

The Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet shows a medium risk of 63%. The universal coverage of the PSM is guaranteed by the contract between the PSM and the government. The risk score of the indicator is raised by low broadband coverage in the general and rural population and low broadband subscription. Internet speed is generally low in the country too. Top4 ISPs hold 97% market share.

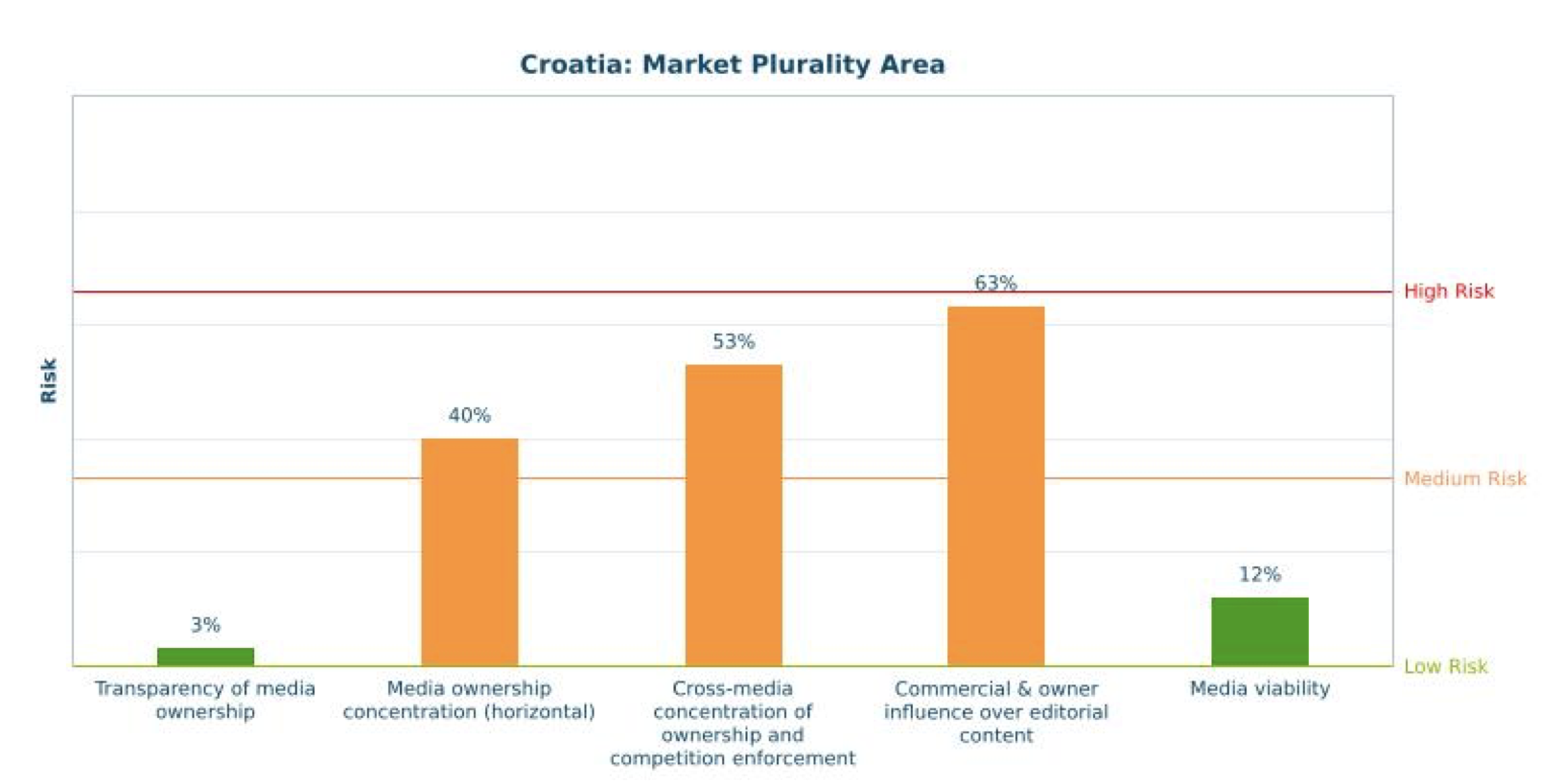

3.2. Market Plurality (34% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Due to the small market, rules on ownership concentration are difficult to enforce. For example, television is the most consumed medium in the country with foreign-based companies having largest audience shares. The market share for the Top4 audiovisual media owners in Croatia is 91% and audience concentration is 77%. The radio market is regionally fragmented. The market share for Top4 radio owners is 46% and audience concentration is 40%. The print media submit a report on ownership changes to the HGK and to the Agency for Market Competition Protection (AZTN). The AZTN does not perform active monitoring but only reacts based on reports by the companies. In recent years it publicly called for the print media to duly report changes in ownership structures in accordance with the law. The market share for the Top4 newspaper owners is 74% and readership concentration 66%. The Media ownership concentration (horizontal) indicator scores a medium risk of 40%.

There is an over-complicated mechanism for monitoring cross-media ownership concentration which involves the HGK, which keeps track of ownership structures for print and print distribution companies, and the VEM, which monitors electronic media. In cases of cross-concentration companies also report to the AZTN. This creates problems for keeping track of the changes and an overlap in regulatory duties between the bodies. The market share of Top4 owners across different media markets is 67%. The market share for the Top4 internet content providers is 62%. Audience concentration for internet content providers is 60%. In cases of cross-ownership there are no safeguards in competition law to protect media pluralism. The rules on disproportionate state aids which ensure that state funding of PSM does not cause disproportionate effects on competition are in place. The VEM monitors its compliance. The Cross media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement indicator shows a medium risk of 53%.

In cases of ownership or editorial line changes the only mechanisms granting some social protection to journalists are the highly ineffective self-regulatory media statutes. There are no regulatory safeguards seeking to ensure that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief are free from commercial interests. The Code of Ethics of the Croatian Journalists’ Association introduces some safeguards to prevent the commercial and advertising influence on journalists. Nonetheless, media owners and other commercial entities systematically influence editorial content. This is reflected in either direct promotion of favourable reports, or a general lack of reports and negative views about major advertisers. The Commercial and owner influence over editorial content indicator scores a medium risk of 63%.

Consistent data on media viability in the media market as a whole is hard to obtain and difficult to evaluate. The revenues for the audiovisual and radio markets seem to be slightly increasing. Print market data was unavailable. Online advertising investments recorded an increase in the past two years. There are weak indications of media organizations seeking non-traditional sources of revenue. Specific support schemes and regulatory incentives for the media sector exists and include, for example, the Fund for the Promotion of Pluralism and Diversity. Overall, the Media viability indicator scores a low risk of 12%.

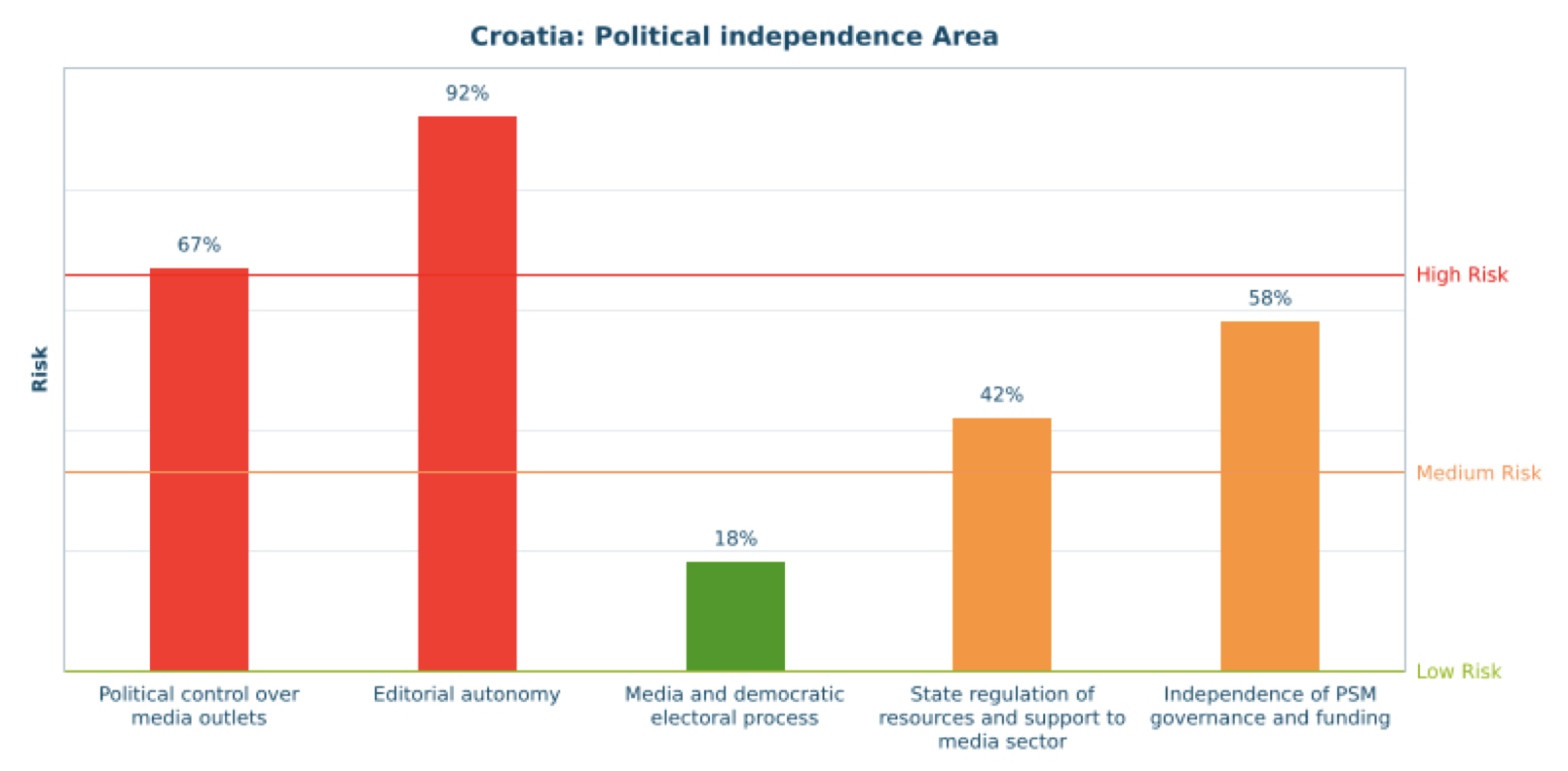

3.3. Political Independence (55% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

There are no explicit restrictions in media legislation that would include limits to party, partisan groups or politicians as owners in the definition. There are cases of conflict of interest between the media, ruling parties and partisan groups. For example, former Minister of Culture allocated public funds to a non-profit portal even though their grant application did not pass the selection by the Expert Committee for non-profit media. Political control over the PSM is particularly evident in the alignment of its editorial policies following parliamentary elections. Radio is especially dependent on regional and local politics while the newspapers often support policies and viewpoints in line with the political leaning of its ownership. The position of the Croatian news agency is deteriorating and is highly susceptible to political influence. The Political control over the media outlets indicator scores a high risk of 67%.

There are systematic cases of political interference in appointment and dismissals of editors-in-chief. This was particularly emphasized in the case of the PSM where dozens of editors and journalists were dismissed immediately following parliamentary elections. Self-regulatory measures such as media statutes and the Code of Ethics of the Croatian Journalists’ Association have proven to be ineffective in controlling political influence. This is one of most troubling indicators in the Croatian media system. For that reason Editorial autonomy indicator scores a high risk of 92%.

It seems that different groups of political actors are represented in a fair way on PSM coverage and private channels and services. However, in the September 2016 elections there were complaints by the political party MOST regarding a public debate on the PSM that included only the presidents of the two biggest parties: HDZ and SDP. As a party gaining supporters and voters, MOST viewed this decision as reflecting negatively on its campaign. The media law does not prohibit, or impose restrictions to political advertising on PSM during election campaigns to allow equal opportunities for all political parties. In other words, the better funded campaigns have a better chance of reaching the voters. Overall, the Media and democratic electoral process indicator scores a low risk of 18%.

There are several mechanisms for the distribution of direct government subsidies to media outlets, including the Fund for the Promotion of Pluralism and Diversity and the redistribution of revenues from the lottery games awarded by the Ministry of Culture though a Non-Profit Media Committee. The role of the Committee was highly politicized and created political controversies. Minister of Culture was found in conflict of interest for allocating funds to a non-profit portal even though the grant application did not pass the selection by the Committee. The Minister of Culture that took office in the short-lived HDZ government (at the beginning of 2016) disbanded the Committee and cut down all the funds for non-profit media as one of his first decisions in office. While there were independence and monitoring issues with the procedure for the allocation of the funds, they could have been improved by more democratic procedures and public debates. The allocation of the funds was transparent and publicly visible although not without some concerns requesting immediate attention. There are also indirect subsidies such as the reduced VAT and the allocation of state advertising. The State regulation of resources and support for the media sector indicator scores a medium risk of 42%.

The PSM management appointment procedures are highly dependent on the Croatian Parliament which leaves room for systematic political interference. Dismissals and appointments often occur after each parliamentary elections. Recent changes of government included more than seventy dismissals ranging from the director to the managers, editors, journalists, engineers, legal experts, and so on. The Director General was dismissed by the Parliament based on a negative report by the Supervisory committee of the PSM. After heated debates the Parliamentary Committee voted against the Director and directly appointed the new acting director. On the other hand, funding of the PSM is adequate and transparent. Overall, the Independence of PSM governance and funding indicator scores a medium risk of 58%.

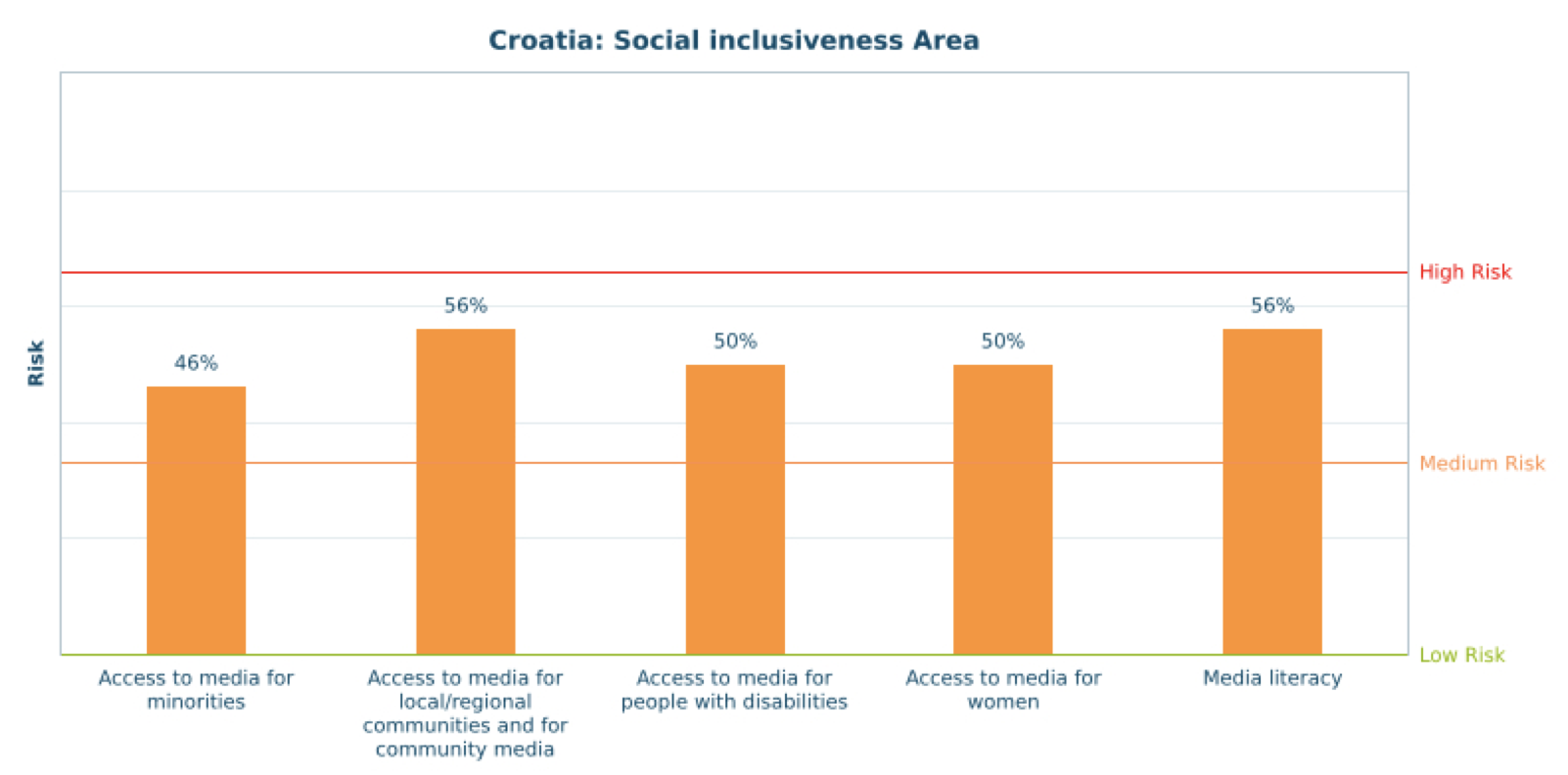

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (52% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

The Monitor indicates that Access to media for minorities is at medium risk of 46%. The law guarantees access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities and the PSM is obliged to have special format programmes for national minorities. Consulted experts for minority issues describe programmes for minorities on the PSM as being ˝ghettoized˝ due to broadcasting time in the least popular time of the day. The legislation does not foresee an obligation to provide national news in minority languages. Minority media receive financial support from the state budget. However, the funds are allocated by the Council of National Minorities creating competition among minority media for limited resources.

Newspapers dedicated to minorities are not proportional to the size of their populations in the country. According to minority experts, publishing activity of most national minority associations supported by the state budget often results in antiquated formats and non-market oriented production. This reduces readership from the national minority communities. The general population is mostly unfamiliar with minority media.

Authorities support regional/local media by a limited number of policy measures or subsidies. The community media have a specific status as non-profit providers of media services and electronic publications as well as non-profit producers of audiovisual and/or radio programmes. They depend on the state budget and there are no legal safeguards for their independence. In particular, the program for the allocation of funds for non-profit media by the Ministry of Culture was lacking sufficient safeguards for fostering political independence. Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores medium risk of 56% according to the Monitor.

The policy on access to media content by people with disabilities is underdeveloped. The existing policies are nascent and the measures taken are fragmented. The media laws require access services for people with disabilities but do not apply to on-demand audiovisual media. The support for people with hearing impairments and blind people in audiovisual media is available only in the least popular scheduling windows. Access to media for people with disabilities is at medium risk of 50% according to the Monitor.

The National Policy for Gender Equality foresees various measures in the field of media such as creating general awareness of gender policies, and funding production and co-production of sensitized media contents. The equal rights law seems to be implemented effectively in the field of media. However, the PSM does not have a gender equality policy. Representation of men and women in the PSM management boards is not well balanced (only 9% are women). The share of women as subjects and sources in news (both on- and offline) is around 30% and presents a medium level of risk. At the same time, the share of women among news reporters is more balanced (50%). Access to media for women is also at medium risk (50%).

Media literacy is set as one of the goals in the educational process in strategic documents. However, the consulted media literacy experts argue that there are no clear indicators, or empirical data, about the level of media literacy in Croatia. Furthermore, the educational system does not enable the development of a critical approach of students towards media content. Apart from being cited in strategic documents, media literacy experts argue, it is not present in the educational curriculum as a separate, or cross-cutting subject. Also in non-formal education the subject of media literacy is present only to a limited extent. Media literacy activities are mostly undertaken by civil society organizations and access to these activities is largely limited to pupils and students living in the capital city of Zagreb. Finally, 65% of Croatians that have used the Internet in the past three months have at least basic digital usage skills and at least basic digital communication skills are also at 65%. The media literacy indicator scores a medium risk of 56%.

4. Conclusions

In 2016 there has been much media policy controversy. Major issues include open political pressure towards the media authority, politicized appointment and dismissal procedures in the PSM, and removal of financial support to the non-profit media sector. Apart from short-term political interference, there are other problematic areas that deserve attention from policy makers. The following is a list of recommendations based on some of the key areas identified by the Croatian country team while carrying out the Media Pluralism Monitor implementation in 2016.

| Basic Protection | ● Ensure better protection of journalistic profession by supporting professional associations and promoting better implementation of self-regulatory statutes and ethics codes.

● Improve the internet broadband coverage in the country. |

| Market Plurality | ● Ensure protection of editorial independence in the Media Act (OG 59/04, OG 84/11, and OG 81/13) and the Electronic Media Act (OG 153/09, OG 84/11, OG 94/13, and OG 136/13). This especially relates to commercial and owner influence over editorial content.

● Establish a single ownership register for all media. A single media authority needs to be designated to monitor compliance of cross-ownership rules. The current institutional monitoring is over-complicated and impossible to coordinate in an efficient manner. |

| Political Independence | ● Expand the definition of connected persons (article 53) in the Electronic Media Act (OG 153/09) to include limits to party, partisan groups or politicians as owners. Introduce a similar definition in the Media Act and ensure limits to political influence on editorial content.

● Re-establish funding schemes for non-profit media while ensuring clear criteria, transparent allocation of the funds and media independence. ● Ensure less political interference in the appointment and dismissal procedures of the PSM management by amending the Croatian Radio-Television Act (OG 137/10, OG 76/12, and OG 78/16). |

| Social Inclusiveness | ● Ensure better representation of minorities in the media system through stable financing for the Council of National Minorities.

● Improve access to media for people with disabilities in prime-time programs. ● Promote the development of a gender equality policy for the PSM. ● Ensure inclusion and consistent implementation of media literacy in the educational curriculum through coordinated action by the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports and the Ministry of Culture. |

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Paško | Bilić | Research Associate | Department for Culture and Communication,

Institute for Development and International Relations |

X |

| Antonija | Petričušić | Assistant Professor | Faculty of Law, University of Zagreb | |

| Ivan | Balabanić | Assistant Professor | Department of Sociology, Catholic University Zagreb | |

| Valentina | Vučković | Assistant Professor | Faculty of Economics, University of Zagreb |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Zrinjka | Peruško | Full Professor | Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb |

| Saša | Leković | President | Croatian Journalists’ Association |

| Nada | Zgrabljić Rotar | Associate Professor | Center for Croatian Studies, University of Zagreb |

| Miroslav | Ivić | Former president | Croatian Employer’s Association – Publishing and Printing Branch |

| Denis | Mikolić | President | National Association of Television Broadcasting |

| Damir | Hajduk | Vice-President | Council for Electronic Media |

| Antonija | Letinić | Editor-in-chief | Kulturpunkt, Kurziv |

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

- 14 December 2016

- Library of the Institute for Development and International Relations (IRMO), Zagreb

- List of participants

Ivan Balabanić, MPM team member

Paško Bilić, MPM Local coordinator

Antonija Čuvalo, Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb

Damir Hajduk, Vice-President of the Council for Electronic Media

Ivana Keser, IRMO

Saša Leković, President of the Croatian Journalists’ Association

Jaka Primorac, IRMO

Mirjana Rakić, President of the Council for Electronic Media

Nada Švob-Đokić, IRMO

Aleksandra Uzelac, Head of the Department for Culture and Communication, IRMO

Dina Vozab, Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb

- Key topics discussed

The meeting opened with a short overview of the history of the Media Pluralism Monitor tool. Afterwards, the methodology for the 2016 implementation was presented. Domains, indicators and variables were explained as well as the group of experts’ process and expert interviews. The discussion focused on the areas that present major risks for media pluralism. In particular, low broadband internet coverage; protection of journalistic profession and standards; political control over media outlets; commercial influence on editorial decisions, cross-media ownership regulation, media literacy issues, and other areas. Finally, media policy recommendations formulated by the MPM Croatia team were presented.

- Conclusions

The stakeholders agreed that more needs to be done to raise the policy impact and public awareness of the MPM 2016 results gathered and presented by the MPM Croatia team. A broader public presentation is suggested once the full narrative report for 30 participating countries is compiled and published by the CMPF.

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/