Read more

Blog, EMFA Observatory

Ownership transparency obligations under Article 6 of the European Media Freedom Act: opportunities and challenges

By Danielle Borges, Research Associate at the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) of the European University Institute (EUI) The European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) included ownership transparency obligations among the duties...

This blog post discusses the evolution of the media capture phenomenon, how the recently adopted European Media Freedom Act will address the related risks, and how the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) developed by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom will monitor its impact accordingly. Designed as a holistic tool aimed at capturing the risks to media pluralism and media freedom through four areas of investigation, the MPM annually provides a risk-based assessment of the situation across the EU Member States and the candidate countries, positioning itself as a key source of information at the European level. The Political Independence area, in particular, collects an extensive set of data to understand the major mechanisms through which political influence is exerted on the media sphere, as well as to track the impact of the most recent regulations at the EU level.

Media capture: an evolving concept

Media and power have always had an intricate interplay, whether in commercial or political. Depending on the historical, socio-political, and technological context, this relationship can tighten or loosen, affecting the manners by which information is conveyed.

After the Cold War period, the ever-evolving political and technological dynamics have further evolved the strategies through which political and commercial powers project influence over editorial content. In the early 2000s, new and peculiar corruptive processes emerged in European countries undergoing post-socialist democratic transition, where the disruption of traditional subsistence mechanisms, struck by the global financial crisis, provoked the exodus of foreign media proprietors. In such a context, recently privatised national media systems were easily plundered by oligarchies affiliated with political power1.

This process was eventually described as ‘media capture’ – or, according to a widely-shared definition by scholar Alina-Mungiu-Pippidi, a situation in which the news media are controlled “either directly by governments or by vested interests networked with politics”2

In this context, another substantial aspect to be considered is the phenomenon’s directionality. That is, the fact that control can be exercised by the power against the media or, vice versa, by the people controlling the media against politics. Based on this, interests have many options to coincide, subvert each other, and of course, clash. Regardless, it is essential to understand that the rationale for owning a media, to put it in Kleis Nielsen’s terms, has moved from profit to power.3

How political capture of the media is investigated and assessed in the Media Pluralism Monitor

While it appears evident that direct and vested interests can be exercised through a wide and non-exhaustive range of mechanisms, the main components of the phenomenon, in the European context, were identified along four dimensions: (1) the capture of the national media authorities that are supposed to regulate the national media sphere; (2) the media takeover though ownership means by intermediaries closely connected to political actors, if not directly by the politicians themselves; (3) the partisan allocation of State resources, such as subsidies or State advertising; and (4), the influence exerted on national Public Service Media through appointment procedures and funding mechanisms on public service outlets.5

In this regard, the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) has collected, since its first edition, a unique set of data. The risks related to direct and indirect control of private media are specifically investigated in the indicator ‘Political independence of the media’, both in terms of ownership control and the control which might be exerted through a dominant influence on the shareholders’ meeting. Potential concerns over the appointment and dismissal procedures for editors-in-chief as well as the effectiveness of self-regulatory measures are the scope of the indicator ‘Editorial autonomy’, while the representation of political actors and viewpoints on PSM and private channels, in the electoral and non-electoral period, has been traditionally assessed through the indicator ‘Audiovisual media, online platforms and elections’.

The Political Independence area has also traditionally looked at the risks related to the partisan distribution of public resources, such as State subsidies and State advertising. The latter, sometimes confused with political advertising – also assessed as a major risk by the MPM – proved to be one of the major mechanisms to capture the media.5 Given their economic vulnerability, media outlets often find themselves dependent on this form of hidden and unregulated subsidization, with huge consequences in terms of editorial autonomy. As to the Public Service Media sector, the MPM provides a specific indicator for the investigation of the risks related to appointment and dismissal procedures for management positions, as well as the risks arising from the PSM funding mechanisms and procedures.

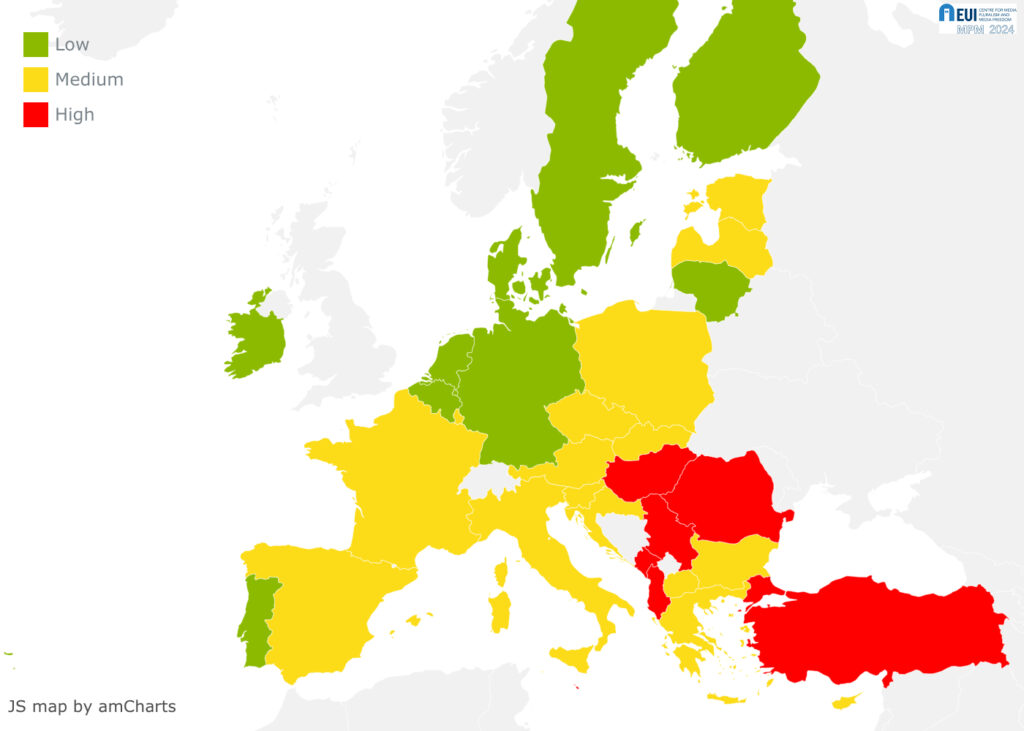

The results of the latest 2024 implementation of the Monitor show an aggregate medium risk score of 48%, with 9 countries scoring a low-risk level, 16 countries scoring a medium risk level, and 7 countries with a high-risk level (Montenegro, Romania, Hungary, Malta, Albania, Serbia, and Turkey).

Geographical representation of risk of the Political Independence area. Source: MPM 2024

As can be easily discerned, the most concerning results are located in the Central and Southeastern parts of Europe, or rather the area where media capture has traditionally proliferated following the dissolution of socialist systems. At the same time, it is essential to bear in mind that significant risks are detected for other European regions as well, with the difference stemming from the intensity of political control on the media, or the presence of risk in some specific sub-fields only.

While the overall risk of the area remained relatively stable in recent implementations, these results confirm not only the significant degree of political leverage across the Member States and candidate countries but, notably, the fact that the risk has not significantly decreased. Quite the contrary: a longitudinal analysis at the indicator level, recently published in the book “Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: legal, economic, social and political lessons learnt from Europe”, reveals that the risks arising from ownership structures, the absence of safeguards ensuring editorial autonomy, as well as the politically motivated distribution of State advertising, all have, on average, shown a risk-increasing trend between the MPM 2018 and MPM 2023. This indicates that “overall, European news media are progressively becoming less secure from political capture compared to the situation seven years ago, which was already far from satisfactory”.6

The research carried out by the CMPF in the context of the Local Media for Democracy Project (LM4D), has demonstrated that most of these concerns are felt at the local level as well, while identifying additional traits of capture specific to the local dimension. An example is the presence of municipal (or local government) media, which in some countries proved detrimental in terms of political control and distortion of the media market. More generally, the research has proved how political capture of the media at the local level can contribute to the formation of so-called “news deserts”, defined as “geographic or administrative area, or a social community, where it is difficult or impossible to access sufficient, reliable, diverse and independent local, regional and community media and information”.7

How the European Media Freedom Act will address the risks of capture, and how the MPM will track the impact in the Political Independence area

In recent years, the persistence of the above-mentioned risks, along with the emerging new ones, have prompted European institutions to propose a wide range of regulatory and self-regulatory instruments, providing the media sphere with a new set of tools and safeguards against the risks of capture in the traditional and the online realm. The European Media Freedom Act, in particular, will address many of the concerning issues identified in the previous paragraphs.

A first, fundamental novelty of the EMFA is the provision on the disclosure of beneficial ownership by media service providers (Article 6), which is likely to bring to public scrutiny the ownership structures that might influence editorial independence.8 While the MPM has already investigated this specific dimension through the indicator Transparency of media ownership (and, to some extent, the indicator ‘Political independence of the media’), it is expected that new data will soon feed the void on hidden political connections and any other uncovered interest which might be piloting the editorial output of the media.

Safeguards have also been provided to protect the editorial independence of Public Service Media. Specifically, Article 5 of the EMFA requires Member States to ensure that the procedures for the appointment and the dismissal of the head of management or the members of the management board of public service media are “transparent, open, effective and non-discriminatory”. As to the funding mechanisms, they shall guarantee that public service media providers “have adequate, sustainable and predictable financial resources corresponding to the fulfillment of and the capacity to develop within their public service remit”. Again, the MPM indicator Independence of public service media has long indicated the risks in these terms: based on the data from the last implementation, it is likely that many Member States will have to reform their PSM provisions, risking infringement proceedings if they fail to do so.10

Notably, the EMFA proposal was also accompanied by the Recommendations on internal safeguards for editorial independence and ownership transparency in the media sector, according to which media service providers are encouraged to adopt a diverse range of rules aimed at protecting editorial integrity and independence. These rules could include, for instance, an editorial mission statement, policies to foster a diverse and inclusive composition of newsrooms, or policies on the responsible use of sources and rules aimed to prevent or disclose conflicts of interest. The Recommendations also encourage media service providers to adopt provisions to promote the participation of journalists in the decision-making of media companies, as well as to improve the sustainability of media service providers and long-term investment in content production.

Similarly to the above-mentioned cases, the MPM indicator Editorial autonomy, the worst-scoring in the Political Independence area (61%, closer and closer to the high-risk band), has identified a generalised lack and/or ineffectiveness of self-regulatory safeguards over the years. Based on the Recommendations, the indicator has now been restructured to capture in an even more granular manner the presence, diversity, and quality of internal and collective self-regulatory measures in the Member States and candidate countries.

Importantly, Article 25 of the EMFA also provided specific measures for addressing the partisan distribution of State advertising, which shall now be awarded to media and online platforms in accordance with “transparent, objective, proportionate and non-discriminatory criteria, made publicly available in advance by electronic and user-friendly means, and by means of open, proportionate and non-discriminatory procedures”. As such, the MPM has integrated a new variable aimed at capturing the transparency of the distribution in online platforms as well. Besides, it will investigate whether national regulatory authorities or bodies or other competent independent authorities or bodies in the Member States monitor and report annually on the allocation.

Finally, based on Art. 21 of the EMFA, the MPM is now provided with a new sub-indicator aimed at detecting any national legislative, regulatory, or administrative measures that are liable to affect media pluralism or the editorial independence of media service providers operating in the internal market, and whether these are duly justified and proportionate.

Conclusion

Media capture is rapidly evolving along with digital developments, which makes it even more difficult to define, both theoretically and practically. As a matter of fact, it is still not entirely clear how traditional control mechanisms are colluding with the new possibilities to exert influence that have emerged with technological advances. Current definitions consider the phenomenon as a “systemic governance problem”9 weakening the mechanisms proper to democratic systems while weaponizing them for illiberal ends. However, while media capture can definitively be understood as a combination of factors, the theoretical framework still seems to be tied to the interpretative structures of traditional media.

To conclude, there is a need for a new conceptual framework capable of connecting the different sub-phenomena, while guiding through the new set of regulations adopted at the supranational level and along EMFA, such as the Digital Services Act, and the recently-adopted Regulation on the targeting and transparency of political advertising.

- See Dragomir, M. (2019). Media Capture in Europe. Media Development Investment Fund. https://www.mdif.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MDIF-Report-Media-Capture-in-Europe.pdf

↩︎ - See Mungiu Pippidi, A. (2008). How media and politics shape each other in the New Europe (pp. 87–100). ↩︎

- See Kleis Nielsen, R. (2017), Media capture in the digital age, in: Anya Schiffrin, ed., In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017) ↩︎

- See Dragomir, M. (2019). Media Capture in Europe. Media Development Investment Fund. https://www.mdif.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MDIF-Report-Media-Capture-in-Europe.pdf ↩︎

- See Nenadic, I., What is state advertising, and why is it such a big problem for media freedom in Europe? /what-is-state-advertising-and-why-is-it-a-problem-for-media-freedom/

↩︎ - See Trevisan, M., Štětka, V., Milosavljević, M. (2024). Tools and strategies of political capture of the media in Europe. In: Brogi, Elda, et al. (2024) Media Pluralism in the Digital Era. Legal, economic, social, and political lessons learnt from Europe. 2024. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Media-Pluralism-in-the-Digital-Era-Legal-Economic-Social-and-Political-Lessons-Learnt-from-Europe/Brogi-Nenadic-Parcu/p/book/9781032567617?srsltid=AfmBOoolm1pvUlRSWa7ATyE5D9cASm2M2Feu9UWiMwrlgetkgOJum0vL ↩︎

- See Verza, S., Blagojev, T., Da Costa Leite Borges, D., Kermer, J. E., Trevisan, M., Reviglio Della Venaria, U. (editor/s), Uncovering news deserts in Europe : risks and opportunities for local and community media in the EU, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, 2024, [Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom] – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/76652

↩︎ - See: https://euideas.eui.eu/2022/10/21/media-ownership-matters-the-proposals-of-the-european-media-freedom-act/

↩︎ - In this blogpost Albanesi has recently identified what could happen in the cases where domestic legislation is not in compliance to Article 5 EMFA after its full implementation on 8 August 2025, and the legal consequences of such an infringement. ↩︎

- See, for example, https://www.cima.ned.org/themes/media-capture/

↩︎