Local Media for Democracy — country focus: Lithuania

Auksė Balčytienė, Vytautas Magnus University and Deimantas Jastramskis, Vilnius University

Context

In Lithuania, the debate about the viability and significance of regional, local and community media is dynamic and has been gradually evolving in the past few years. Likewise, the concept of “news deserts” has found its place in mediated discussions. Groups engaged in public discussions include representatives of minority group associations, regional journalists, experts from professional media organisations (such as the Lithuanian Union of Journalists), academics and researchers, freelancers, experts from different Think-Tanks (Vilnius Political Analysis Institute, Transparency International), policymakers, and representatives from the media regulatory authorities (such as the Radio and TV Support Fund).[1]

The main media law “The Provision of Information to the Public”[2] contains the definition of “regional media”, whereas there are no institutionalised definitions for “community media” and “local media”. In academic studies, “community media” is most often described as media outlets produced by non-profit organisations accountable to the community they seek to serve.

Lithuania consists of two NUTS2 regions: the Capital region and the Central and Western Lithuania region. The GDP per capita of the Capital region was almost twice (43,100 euro) as high as that of the Central and Western Lithuania region (23,200 euro) in 2021. In this analysis, three areas—Druskininkai Municipality, Širvintos District Municipality and Visaginas Municipality—were identified as exhibiting characteristics of “news deserts”. Political-business influence emerges as the most significant factor in determining news deprivation. At the same time, it is not possible to say whether the most economically or technologically deprived areas overlap with those regions identified as “news deserts”. This ambiguity also extends to technological advancements. Lithuania is evenly covered by internet access, which, according to the calculations provided by the Communication Regulation Authority, the RRT (Ryšių reguliavimo tarnyba), stands at 99%, with the few exceptions of border regions in Varėna, Ignalina, Šalčininkai, and Pagėgiai.[3]

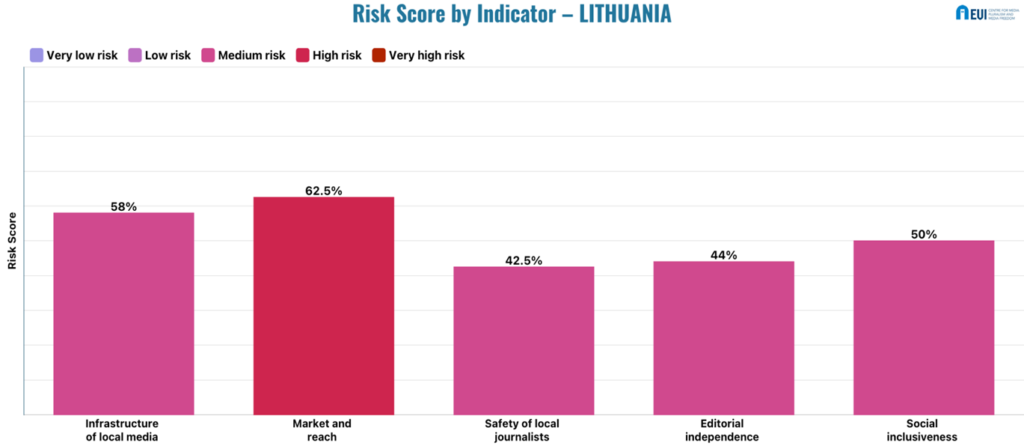

In essence, as revealed on the bar chart below, the risks in the decline of news affecting the local media landscape are more strongly linked to political and business alignments, a diminishing professional independence and infrastructural conditions (media viability and news distribution models), than being directly attributed to purely regional-economic[4] matters or to those relating to accessibility to digital-technological information.

[1] Atsako žiniasklaidos ekspertai: ar Lietuvos regioninei žiniasklaidai gresia pasaulinė „žinių dykumų“ tendencija? [Media experts respond: is Lithuanian regional media threatened by the global trend of “news deserts”?], 2023, https://www.delfi.lt/m360/medijos/atsako-ziniasklaidos-ekspertai-ar-lietuvos-regioninei-ziniasklaidai-gresia-pasauline-ziniu-dykumu-tendencija-93293091; J. Naglienė and B. Sabaliauskaitė, Medijų ir informacinio raštingumo savaitė apnuogino skaudžią tiesą: Lietuvoje didėja žinių dykumos Skaitykite daugiau, 2023, https://www.delfi.lt/m360/medijos/mediju-ir-informacinio-rastingumo-savaite-apnuogino-skaudzia-tiesa-lietuvoje-dideja-ziniu-dykumos-95002917.

[2] Sections 44 and 45 of Article 2 of the Law on Provision of Information to the Public define regional newspaper and broadcaster: “44. Regional newspaper – a newspaper that is distributed in the territories of the counties of the Republic of Lithuania and whose circulation is not less than 90 percent in the territory of one county; 45. Regional broadcaster – a broadcaster whose programme broadcast by terrestrial television or radio network is received in the territory where less than 60 percent of the population of Lithuania lives”. Legal act, Lietuvos respublikos visuomenės informavimo įstatymo pakeitimo, 2006, https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.280580.

[3] In 2023, three market participants (Telia Lietuva, Tele2 and Bitė Lietuva) were obliged to ensure the provision of universal electronic communication services in these districts. It was shown they covered less than 95 percent of all residential premises in the relevant municipality.

[4] Lithuania experienced successful economic growth until early 2022 but has since faced setbacks due to Russian aggression in Ukraine. In 2022, the Lithuanian economy slowed down, and quarterly growth was weak throughout the year, culminating in a negative growth rate of -1.7% in the fourth quarter. In 2022, inflation reached 18.9%, but the rate of price growth was projected to decrease in 2023. In response to inflation, the government has been supporting households and businesses to help them cope with the energy crisis. Infliacijos skaičiuoklė, https://paslaugos.stat.gov.lt/; According to the Bank of Lithuania, in 2022, the unemployment rate was 5.9%, which is less than in the previous year (2021 it was 7.2%).

Main findings

Granularity of infrastructure of local media – Medium risk (58%)

The critical question of serving the public interest in the local area has become increasingly relevant in the past five to seven years. In all types of public discussions in the media[1], the objective of regularly serving regional and rural communities,[2] especially during important times such as political elections, is often framed in the context of “existential questions” for regional media. The questions often revolve around ensuring the financial viability of regional news, maintaining an informed readership, which indirectly also affects journalistic professionalism, and upholding the political independence of the media.[3] In the regions, subscription is a major guarantor of the financial sustainability of newsrooms, and editorial offices base all their sustainability and marketing activities around it.[4]

There are certain forms of media outlets in suburban areas of towns in Lithuania, among which radio (digital broadcasts) and online media are the most popular platforms. In the Kaunas region, the news portal Kas Vyksta Kaune[5] is among the best examples of a regional media outlet which covers all suburban areas of the city by including citizen announcements. An example of collaborative partnerships in the development of news exchanges on a regional level is the weekly Etaplius. For over a decade, it has been overseeing the regional news exchange platform www.etaplius.lt, covering news from 60 outlets and drawing in over 60 thousand users per day.

It is becoming quite common for information to reach local communities online, since many urban, regional, and local media have restructured their operations to provide online news. However, the critical factor is the audience’s ability to access news in such a manner. Lack of sufficient digital skills[6] and the preferences for more conventional types of media among the older population might be one of the major factors preventing further operability of online media in the regions.[7]

The number of regional media journalists varies across the country.[8] The largest concentration of media professionals is in the capital city where all the dominant news media are based.

As a tradition, regional and local news media aim to have journalists on the spot and many outlets strive to keep their newsrooms functioning, albeit the number of journalists and other professionals is very small.[9] A further big problem is the age of a journalist; younger journalists are not keen on living in rural areas or localities further away from urban centres. Cooperation on initiatives and projects initiated by teams of journalists based in urban centres is a good possibility for the professional advancement of regional journalists.

Lithuanian National Radio and Television (the LRT, Lietuvos radijas ir televizija), the public service broadcaster, has a regional studio in Kaunas with radio and TV journalists and assisting personnel, and a network of correspondents in other bigger cities. This relatively limited arrangement reflects a long-standing tradition, rather than a newer strategy of the LRT, which focuses on maintaining a network of correspondents abroad, such as in Brussels and Washington. Two news agencies, BNS (Baltic News Service) and ELTA (Ereto Lietuvos naujienų agentūra), operate in Lithuania and both are based in Vilnius. BNS has its correspondents in the second largest city, Kaunas. BNS maintains a platform of news exchanges with regional media. There is a growing need for news agencies to maintain a foundation of accurate information while keeping up with people’s news preferences, expanding on news presentation styles and formats. Specifically, news agencies need to restructure themselves and “democratise from within,” which means granting more accessibility to audiences and being more sensible to the audiences’ needs.[10]

[1] Atsako žiniasklaidos ekspertai: ar Lietuvos regioninei žiniasklaidai gresia pasaulinė „žinių dykumų“ tendencija? [Media experts respond: is Lithuanian regional media threatened by the global trend of “news deserts”?], 2023, https://www.delfi.lt/m360/naujausi-straipsniai/atsako-ziniasklaidos-ekspertai-ar-lietuvos-regioninei-ziniasklaidai-gresia-pasauline-ziniu-dykumu-tendencija-93293091.

[2] J. Naglienė and B. Sabaliauskaitė, Medijų ir informacinio raštingumo savaitė apnuogino skaudžią tiesą: Lietuvoje didėja žinių dykumos Skaitykite daugiau, 2023, https://www.delfi.lt/m360/medijos/mediju-ir-informacinio-rastingumo-savaite-apnuogino-skaudzia-tiesa-lietuvoje-dideja-ziniu-dykumos-95002917.

[3] R. Malychas, Ryšių su skaitytojais konstravimas Lietuvos rajoninių laikraščių redakcijose [Construction of relations with readers in the editorial offices of Lithuanian regional newspapers] MA Thesis. Vytautas Magnus University: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2022.

[4] Ibid.

[5] News portal Kas Vyksta Kaune official website, https://kaunas.kasvyksta.lt/.

[6] A. Balčytienė, et al. Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era : application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. Country report : Lithuania, EUI, RSC, Research Project Report, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), 2023, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75729/lithuania_results_mpm_2023_cmpf.pdf?sequence=1.

[7] R. Malychas, Ryšių su skaitytojais konstravimas Lietuvos rajoninių laikraščių redakcijose [Construction of relations with readers in the editorial offices of Lithuanian regional newspapers] MA Thesis, 2022, Vytautas Magnus University: Kaunas, Lithuania.

[8] D. Jastramskis, Lithuanian journalism in the vortex of economic risks. The 15th Conference on Baltic Studies in Europe. Turning Points: Values and Conflicting Futures in the Baltics, 2023, Vytautas Magnus University.

[9] Ibid.

[10] V. Bruveris: naujienų agentūros turi plėsti savo stilius ir formatus [The news media must work to diversify their reporting style and format], 2023, https://www.delfi.lt/projektai/elta-100-ziniasklaidos-veidu-ir-metu/v-bruveris-naujienu-agenturos-turi-plesti-savo-stilius-ir-formatus-93845315.

Market and reach – High risk (62,5%)

Conventional local media are slowly withdrawing from the market. This can be seen in recent years in the newspaper and audio-visual media sectors. There are only six local television stations in Lithuania, which broadcast news usually only once a day. Local radio stations also operate in less than a third of municipalities. Local newspapers, published in most municipalities, remain the dominant media. Media concentration in local markets is naturally high, as individual markets usually have only a few media outlets.

Most local newspapers are for sale and subscription; the tradition of paid press continues. The newsrooms of local newspapers and new market participants develop local websites. However, the digital press in municipalities is very difficult to commercialise (digital subscription rates in local media are still low), and newspapers remain the main media on the whole.

The daily reach of local radio stations during the last five years (2018-2022) has been relatively stable.[1] However, the total annual circulation of Lithuanian newspapers (including local outlets) decreased by a third from 2017 to 2021.[2] The number of real users of regional/local websites increased in 2022-2023, and the audience shares of some regional websites also increased in 2019-2022.[3]

The revenue of most local media organisations decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021 and increased in 2022.[4] However, this revenue increase in many cases did not reach the inflation rate.[5] It is possible to state a general decrease in advertising revenue in the local media, with a certain reservation, when evaluating the online-only sector.

The Lithuanian Government partly subsidises the distribution of the periodical press to rural areas. Five percent VAT exemption is applied for the sale and subscription of newspapers, magazines, and the electronic press.[6] Direct subsidies to local media are administered by the Press, Radio, and Television Support Foundation (the Media Support Fund since 2024). Although funding from the state budget for this fund in 2022 increased by 0.5 million euro compared to 2021, state support is insufficient to make local media more economically sustainable.[7] The legislation does not provide universal rules for the advertising of state and municipal institutions in the media. State and municipal institutions, when organising tenders for the purchase of advertising in the media, determine the requirements for advertising in their separate decisions. Moreover, there are no available funding sources for local media outlets that aim to promote innovation.

[1] Kantar, Metinė media tyrimų apžvalga [Annual review of media research], 2023, https://www.kantar.lt/lt/top/paslaugos/media-auditoriju-tyrimai/metine-media-tyrimu-apzvalga.

[2] LNB, Lietuvos leidybos statistika, 2023, https://www.lnb.lt/istekliai/leidiniai/kiti-leidiniai/lietuvos-spaudos-statistika

[3] Gemius Audience, Websites, 2023, https://e-public.gemius.com/lt/rankings/9791.

[4] Rekvizitai, Duomenų rinkmenos [Data files], 2023, https://rekvizitai.vz.lt/.

[5] Oficialiosios statistikos portalas, Metinė infliacija [Annual inflation], 2023, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/pagrindiniai-salies-rodikliai.

[6] Republic of Lithuania Law on the Value Added Tax, 2022, https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.ED68997709F5/asr.

[7] R. Balčiūnaitė, Medijų rėmimo fondo biudžetu nepatenkinta žiniasklaida prašo institucijų didinti finansavimą [Unsatisfied with the budget of the Media Support Fund, the media ask the authorities to increase funding], Vz.lt, 2023, https://www.vz.lt/rinkodara/medijos/2023/10/26/mediju-remimo-fondo-biudzetu-nepatenkinta-ziniasklaida-praso-instituciju-didinti-finansavima#ixzz8LgGZXz2G.

Safety of local journalists – Medium risk (42,5%)

Most local media journalists work under employment contracts; about 20% are freelancers. The salaries of journalists working in the local media are, on average, lower than the average salary in Lithuania. Thus, the money allocated to social guarantees (especially unemployment benefits and pension insurance) is also lower than the national average. Local media freelancers earn similar incomes to contract journalists, but freelancers receive lower social guarantees. [1]

In 2022, some local media organisations have had to reduce staff numbers, and salaries have remained significantly unchanged.[2] However, given approximately 20% inflation in Lithuania, the income (or purchasing power) of many journalists relatively decreased.

There are no registered cases of physical attacks and threats against local media journalists in Lithuania in 2018-2022. However, psychological harassment and online threats or other intimidation are occasional occurrences in the activities of local media journalists.[3] In recent years, investigative journalists from national organisations have faced vexatious lawsuits (SLAPPs) but there have been no similar cases in local organisations.

Some local media journalists are members of professional organisations. The Lithuanian journalists union has its branches in several major cities. However, most journalists do not belong to professional associations. Professional journalistic organisations assist their members in difficult work situations in individual cases, but this does not happen systematically. The activity of professional organisations in ensuring editorial autonomy and professional standards is quite limited. Therefore, journalists do not always trust professional organisations and try to solve the problems on their own.[4]

[1] D. Jastramskis, Lithuanian journalism in the vortex of economic risks. The 15th Conference on Baltic Studies in Europe. Turning Points: Values and Conflicting Futures in the Baltics, 2023, Vytautas Magnus University.

[2] Sodra.lt, Įmonių paieška [Search for companies],2022, https://atvira.sodra.lt/imones/paieska/index.html.

[3] R. Juknevičiūtė, D. Donauskaitė and L. Tubys, Žurnalistų darbas interneto amžiaus pradžioje. Iššūkiai saugumui, privatumui, reputacijai [The work of journalists at the beginning of the Internet age. Challenges to security, privacy, reputation], 2020, https://lzc.lt/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Zurnalistu-darbas-internete.pdf.

[4] D. Jastramskis, Lithuanian journalism in the vortex of economic risks. The 15th Conference on Baltic Studies in Europe. Turning Points: Values and Conflicting Futures in the Baltics, 2023, Vytautas Magnus University.

Editorial independence – Medium risk (44%)

The indicator editorial independence scores 44% (medium-risk). Lithuanian politicians, civil servants, and spouses have ownership rights to over 100 media outlets.[1] Such media ownership is more common in municipalities where a large part of the local media is financially dependent on politicians. As a result, it is quite difficult for some local media organisations to apply journalistic professional standards related to editorial autonomy and impartiality.

The economic weakness of local media organisations and the insufficient state subsidisation efforts mentioned in the market and reach section, pose serious risks to the independence of local media content. At the same time, direct state subsidies to private local media outlets are distributed quite fairly and transparently. However, the distribution of state advertising to media organisations is not always fair and transparent. Unclear schemes for the distribution of state advertising money through communication agencies to the media outlets create conditions for corruption.[2]

Survey data of Lithuanian journalists show that more than two-thirds of journalists working in the regions (local media) recognise the influence of advertising decisions on their journalistic activities.[3] Such dependence of journalistic work in local organisations on political and commercial influences shows that in most cases local media cannot professionally cover all important topics and adequately inform their audience about local political and social problems. The economic weakness of local private media often creates conditions for corrupting editorial offices through municipal advertising services. This way, some political opinions are highlighted, while others are belittled or silenced. In practice, there are cases when journalists of local newsrooms are bound by obligations to local authorities.

Lithuania has three media authorities: the Journalist Ethics Inspector, the Lithuanian Radio and Television Commission and the Public Information Ethics Commission. None of these institutions have local branches. However, they oversee both national and local media. These media authorities act independently.

From 2023, the Lithuanian public media service focuses its news strategy more on the regions and is committed to reflect the current affairs, issues, and opinions of the residents of all regions of Lithuania on LRT channels.[4] However, comprehensive information also requires appropriate resources, while a total of eight journalists work in the Lithuanian National Radio and Television branches (in the five largest cities of Lithuania excluding the capital).

It can be summarised that commercial local media experience significant political and economic constraints, often not being able to inform their communities more effectively; the public media service is not always able to fill the emerging information gaps in each region. There is a partial diversity of content.

[1] BNS, Pernai Lietuvoje kas aštunta žiniasklaidos priemonė buvo valdoma politikų [Every eighth media outlet in Lithuania was controlled by politicians last year], 2022, https://www.vz.lt/rinkodara/medijos/2022/06/23/pernai-lietuvoje-kas-astunta-ziniasklaidos-priemone-buvo-valdoma-politiku.

[2] M. Aušra, LRT tyrimas. Milijonai eurų nuomonei pirkti – kalbama apie šešėlines schemas žiniasklaidoje [LRT investigation. Millions of euros to buy opinions – shady schemes in the media], Lrt.lt, 2019, https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lrt-tyrimai/5/1094176/lrt-tyrimas-milijonai-euru-nuomonei-pirkti-kalbama-apie-seselines-schemas-ziniasklaidoje.

[3] D. Jastramskis, Lithuanian journalism in the vortex of economic risks. The 15th Conference on Baltic Studies in Europe. Turning Points: Values and Conflicting Futures in the Baltics, 2023, Vytautas Magnus University.

[4] LRT, LRT 2023-2027 metų strategija [LRT 2023-2027 strategy],2022, https://apie.lrt.lt/api/uploads/LRT_strategija_2022_horizontal_final_2022_11_23_ikelimui_93fed5d08f.pdf.

Social inclusiveness – Medium risk (50%)

Based on the 2021 general population and housing census, approximately 2 million 810 thousand people lived in Lithuania. Out of this population, 432 thousand representatives of national minorities were identified. This accounts for approximately 15 percent of all Lithuanian residents.

Lithuanian Radio and Television (the LRT) is obliged to provide news in minority languages as part of its programming strategy and mission. The programmes and types of news offered for minority communities on various channels vary based on their specificities: there are original TV programmes produced in Polish, Yiddish, Russian and Ukrainian. As for the internet media, the Lrt.lt website features dedicated pages in Russian, Polish, and English.

The LRT implements the strategy of inclusion, particularly on age groups such as children and seniors, as well as gender (assuring adequate representation of women in news programmes) and addressing minority issues.

The 2020 research data by a monitoring company “Mediaskopas”, indicates that the media’s efforts to change towards more fair representation are evident, but the emphasis on ethnicity, especially in the context of crime reporting, remains a pressing issue.[1] Cases of hate speech directed at national minorities tend to increase during important national events, such as parliamentary elections. Again, it is important to acknowledge that this trend is more characteristic of commercial media rather than public service media.

Some of the major commercial news outlets offer news coverage in minority languages. Among these are the internet media (Delfi.lt) which has a dedicated Russian-language newsroom, albeit with a smaller team of journalists. Nevertheless, they cover the main news and provide fact-checks.

The media support system, including the new model of media support, Media Support Fund (Medijų rėmimo fondas), does not identify marginalised people as an audience group with specific needs. Currently, the “Law on Provision of Information to the Public” stipulates that the Media Support Fund allocates support to the projects of registered public information producers and disseminators according to certain programmes and priority areas. Among these are education and culture-related themes, media literacy-related matters, investigative and educational journalism, and other programmes.

In most cases, local media outlets, if they are available in the region, are connected to their audiences and invest efforts to maintain community engagement. It is very often the job of local journalists and media professionals, librarians, teachers, museum workers and religious leaders to serve as core community centres around which local communities gather. Yet, many regional and local media face serious economic sustainability challenges. Therefore, political and business linkages might be problematic. Some critical regions, such as Širvintos and Druskininkai, face limited public scrutiny, while others perform well in terms of media coverage and provision of public interest type of information.

[1] National minorities such as Roma, Poles, Russians, and Jews can be found in up to 72 percent of all mentions of hate speech in Lithuanian media. Manoteises.lt, Ištyrė, kas sumažintų neapykantos kalbos srautą tautinių mažumų atžvilgiu,2021, https://manoteises.lt/straipsnis/istyre-kas-sumazintu-neapykantos-kalbos-srauta-tautiniu-mazumu-atzvilgiu/.

Best practices and open public sphere

Lithuania provides several examples of innovative local community media. One notable case is news portal Kas Vyksta Kaune: with over 10 years history, established as a civic initiative on social media (Facebook) for news exchanges among the people in the city, it has evolved into an online platform with an integrated news portal and social media channel. Over time, it has grown to set and shape the regional news agenda and actively participate in city events. Initially established to bridge news events and citizens in Kaunas, Kas Vyksta Kaune functions as a newsroom with approximately seven professional journalists, editors and IT specialists; additionally, it serves as a hub for internships for journalism, communications, and IT students.

The Bendra.lt project, initiated by the Media4Change organisation, is an innovative venture of “inclusive local journalism”. It provides an engaging hybrid platform which runs both digitally (as a news portal) and face to face meeting sessions for exchanges between citizens and a team of journalism professionals. The team’s task is to further develop ideas offered by citizens into journalistic products.

The third example comes from local suburban media outlets (Gyvenukaune.lt, Gyvenujurbarke.lt, Gyvenuplungeje.lt), initiated and produced by independent journalists directly accountable to their local communities. Traditionally, these media types do not rely on one funding scheme to guarantee their viability; instead, they operate on a project-basis, through crowd-funding initiatives, partnering with other local knowledge organisations (schools, libraries, museums) and using advertising.