Download the report in .pdf

English – Dutch

Authors: M.H. Paapst (ICTRecht BV; University of Groningen); T. Mulder (University of Groningen)

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF.

In the Netherlands, the CMPF partnered with M.H. Paapst en T. Mulder, who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

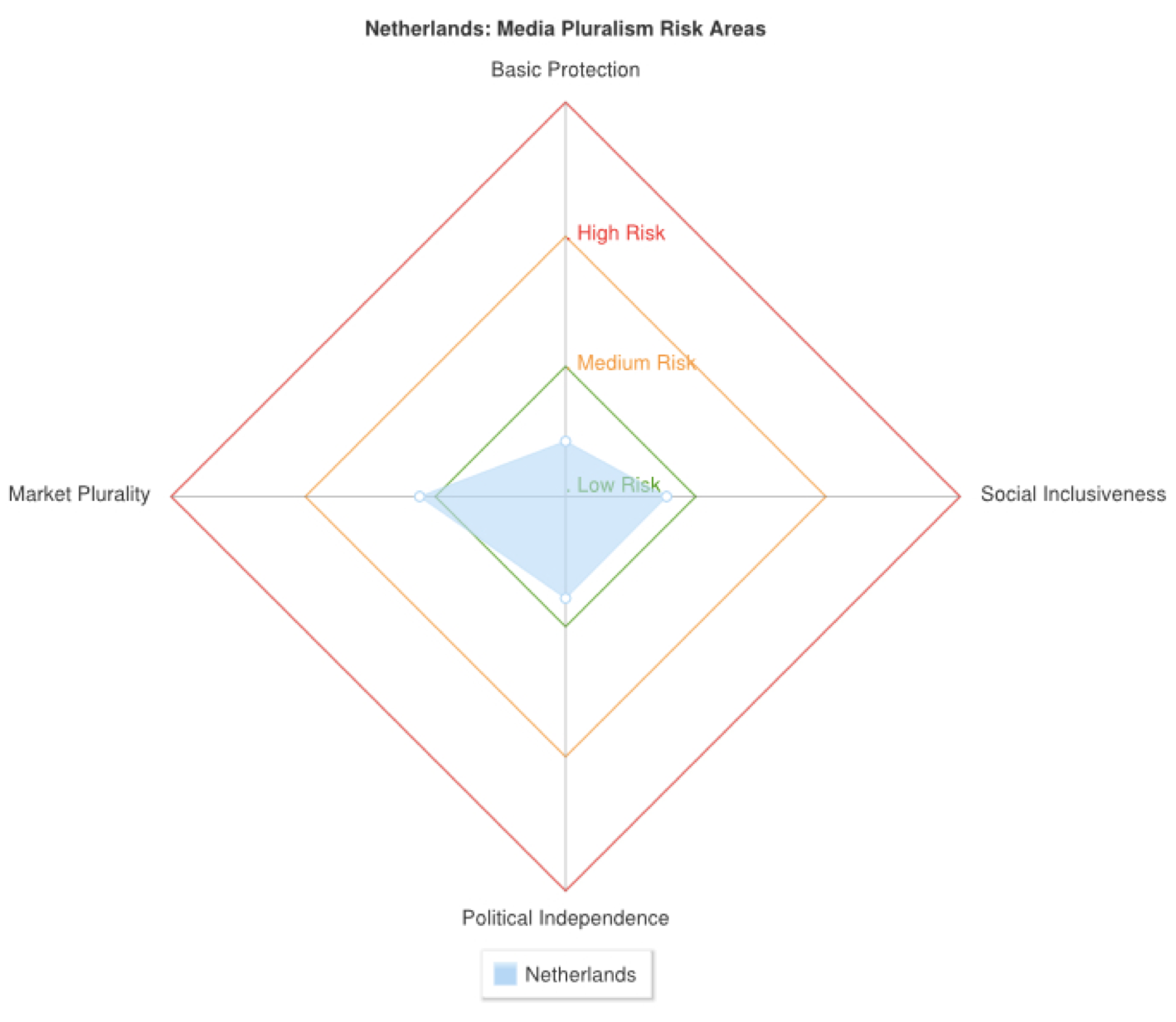

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

The Netherlands, a relatively small country in the north-west of Europe, has a little over 17 million inhabitants.[2] The officially spoken language is Dutch. 22% of the inhabitants are originating from another country, of which 44% from Western countries and 56% from non-Western countries.[3] The largest non-Western minority groups are the Turks (approx. 320.000) and the Surinamese (approx. 300.000), who are both not officially recognized as a national minority. The Frisians are the only minority recognized by law.[4]

The representation of religious and philosophical groups is guaranteed by the Nederlandse Publieke Omroep (Dutch Public Broadcasting, NPO). The Dutch Media Authority issues national airtime to religious and philosophical broadcasting associations. The main broadcasting associations – NTR, EO, KRO-NCRV and VPRO/HUMAN – do take care of airtime targeted at religious and philosophical groups as of 1 January 2016.

The economy in the Netherlands is growing steadily, for the 8th quarter in a row.[5] The political situation is stable but fragmented, with, just to illustrate, 28 different political parties taking part in the 2017 general elections.

There is a strong tradition in regard to freedom of the press, and the Dutch public media system is characterized by various associations that represent different societal groups. The journalistic culture in the Netherlands is characterized with freedom of speech, plurality and self-regulation and has a strong tradition concerning ethic codes and codes of conduct. Media owners could have political ties of any kind, but there are no signs of political control over the newspapers, radio or television channels.

The largest media outlets based on their audience share are:

De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad (newspapers),

Radio 538, NPO Radio 3FM (radio channels),

NPO Nederland 1 and RTL4 (television channels).

For print media the largest publishers are TMG (Telegraaf Media Groep) en De Persgroep. The largest national and regional newspaper publishers have a partnership to collectively distribute their newspapers. The Holland Media Combinatie is making use of TMG Distributie for the physical distribution.

For radio and television the three largest distributors are Ziggo (33%), KPN (30%) and UPC (16%). Liberty Global owns UPC and took over Ziggo in 2015. After the consolidation that took place in 2016, Ziggo became the largest distributor in the Netherlands.

The assessment completed for this report was conducted between June and October 2016, thus not taking into account any new developments since then.

The authors wish to thank the panel of experts and consulted professionals, institutions and academics for providing information and insight.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The Netherlands scores low risk in the areas of Basic Protection, Social Inclusiveness and Political Independence, as can be seen in the figure below. As for Market Plurality the country scores medium risk.

For each of the domains, the results are discussed by indicator.

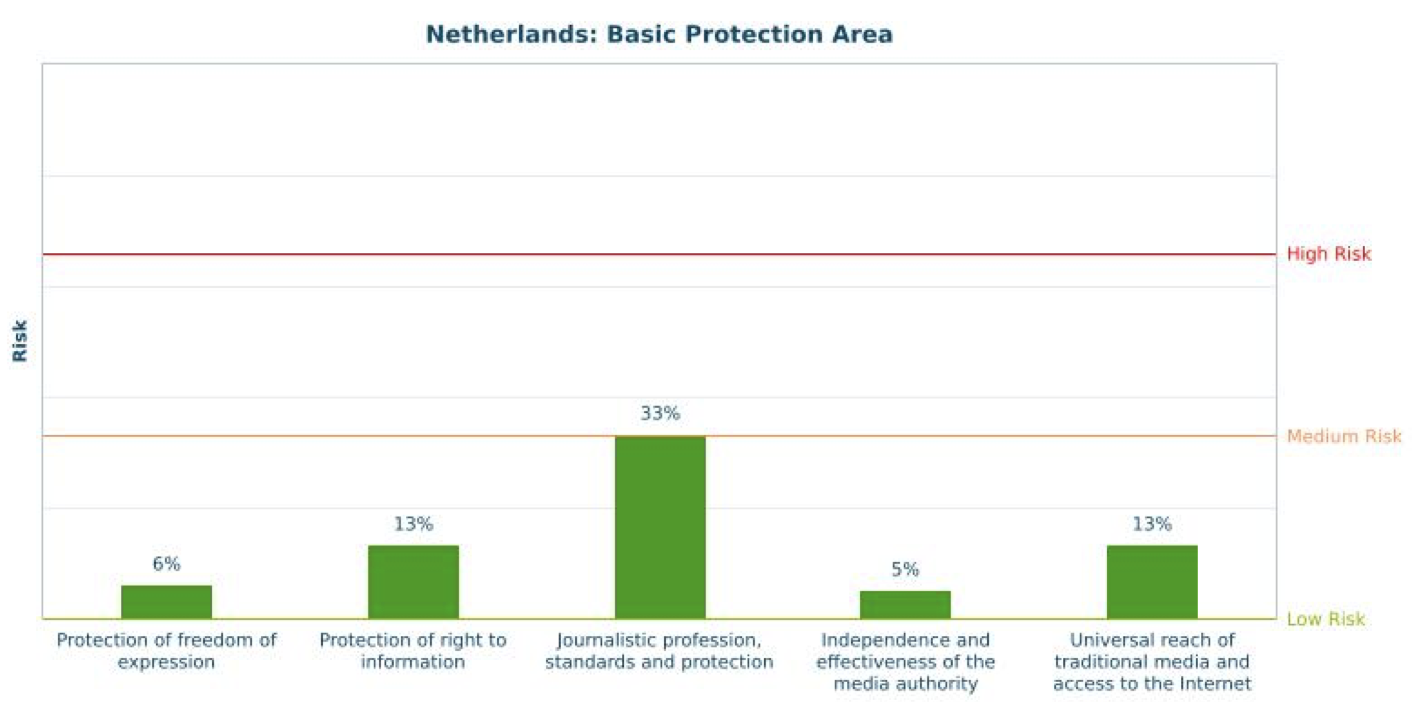

3.1. Basic Protection (14% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

All indicators in the Basic Protection area indicate a low risk. This implies that the Netherlands have a solid legal framework for media pluralism. There are although some remarks that are worth mentioning.

Protection of freedom of expression scores a very low risk (6%). The legal protection of freedom of expression does not show any substantial problems. In the Dutch Constitution freedom of expression is guaranteed and no explicit restrictions are made. Restrictions can however be found in national laws and regulations such as the Dutch Penal Code. This also means it is easy to change these restrictions depending on the political parties ruling the country. If we look at the way freedom of expression is respected in practice, and look for indications that the laws safeguarding freedom of expression may be ineffective, we see that according to the Persvrijheidsmonitor 2015 there are some examples of minor incidents over the last three years.[6] Still a low risk is indicated as these incidents are not considered common practice.

Protection of right to information also scores a low risk (13%). Along with the Freedom of expression, the Dutch Constitution gives people the right to receive information. For public information that right has explicitly been granted in the Act on the Openness of Governance (Wet Openbaarheid van Bestuur). The act regulates how individuals can get information on administrative matters in documents, held by public authorities or companies carrying out work for a public authority. Recently a new bill got approved by the House of Representatives that will replace the Act on Openness of Governance (Wet Openbaar Bestuur, WOB) with the Act Open Government (Wet open overheid). This bill still (October 2016) needs approval of the Senate.

There are no explicitly mentioned appeal mechanisms in Dutch law concerning protection of right to information, but based on administrative law, appeal can be filed against decisions of government bodies in general. Procedural rules for this are laid down in de General Act on Public Administration (Algemene wet bestuursrecht, article 7:1). The Courts of First Instance are competent for the complaints with regard to the right of access to information, and a complainant can go to the Council of State for an appeal decision.

The indicator on Journalistic profession, standards and protection scores a low risk, but on the border to medium (33%). Journalism is a free profession in the Netherlands. This means that everybody is able to call himself a journalist, there are no restrictions or legal requirements and no licensing is necessary to call yourself a journalist. This is one of the reasons that there are about 16.000 journalists in the Netherlands. Of these 16.000 journalist approximately 75% is unionized. The main reason why the indicator almost scores a medium risk is because of the current lack of regulatory safeguards for the protection of journalistic sources. Protection of journalistic sources is not enshrined in Dutch statutory law. In September 2014, the Dutch legislator issued two bills on the protection of journalistic sources. The bills follow several judgments against the Netherlands for violating Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (Europees Verdrag voor de Rechten van de Mens) in cases concerning journalists and source protection. With three violations on the matter in the last seven years (Voskuil v. the Netherlands in 2007; Sanoma Uitgevers B.V. v. the Netherlands in 2010; and Telegraaf Media Nederland Landelijke Media B.V. and Others v. the Netherlands in 2012). The Dutch government has been repeatedly criticized by the European Court of Human Rights for not having legislation in place that legally guarantees the protection of journalistic sources. Therefore, with these new bills, source protection issues in the Netherlands will be regulated under two new laws. The process towards these new laws took quite some time and has been suspended for several reasons.

Independence and effectiveness of the media authority scores a low risk (5%). The Dutch media authority is called the Commissariaat van de Media. Board members of this authority are, according to article 7.4 Media Act, not allowed to: 1. have a membership in the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer), the Senate (Eerste Kamer) and provincial or municipal administration 2. be employed within any ministry of an institution under the responsibility of a ministry 3. be employed with a public or commercial broadcasting, or relating institutions, or publisher. At the head of the authority are three board members (June 2016), which have been appointed by the Minister of Education, Culture and Science.

The minister can dismiss an individual board member, but only for well-defined reasons, which are specified in the law (e.g. incapacity, or because the board member requested it). We consider this to be a low risk, since the Minister had only two reasons to dismiss an individual board member and there were no early dismissals in the last years.

According to the last evaluation of the inner working of the authority, the Government only overruled two decisions during the period 1989 till 2011. This was done because the overruled decisions were not considered to be legally valid, or were not seen as taken in the national public interest.[7] There are no recent cases known where decisions are being overruled by the government.

Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet is also a low risk indicator (13%). This value is due to the existence of laws that prescribe national coverage for the television channels of the Dutch Public broadcaster (NPO). Transmission should take place without any additional costs for the end user. According to telecommunications operator KPN, the DVBT network (Digitenne) can be received in almost the whole country (KPN, 2015). TV scan (2015) draws a similar conclusion It is also arranged by law that the Dutch Public broadcaster (NPO) has national coverage for its radio channels. According to fmscan.org (2016), the Dutch public broadcaster’s (NPO) main radio channels (these are NPO Radio 1, NPO Radio 2, NPO 3FM, NPO Radio 4) have a technical reach (via FM frequencies) all over the Netherlands. When we assess the broadband coverage in the country, a percentage of 99,99% of the population is covered. We considered this to be a low risk. The average internet connection speed is 18 Mbps. Assessing the ownership concentration of the ISPs in the country we conclude that in 2014, the three biggest ISPs together hold a 84% marketshare: KPN (40%), Ziggo (28%) and UPC (16%). In 2015 UPC and Ziggo merged into one company.

3.2. Market Plurality (37% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The indicator on transparency of media ownership scores a low risk (3%) The national law contains transparency and disclosure provisions that oblige both listed and non-listed media firms to disclose their ownership structures in records/documents that are accessible to the public, and to report ownership structures to the public authorities.

The indicator on media ownership concentration (horizontal) indicates a high risk in the Netherlands with 83%. Since 2011 the country does no longer have media legislation containing specific thresholds and/or other limitations that are based on objective criteria (e.g. number of licences, audience share, circulation, distribution of share capital or voting rights, turnover/revenue, etc.) in order to prevent a high degree of horizontal concentration of ownership in the media sector.

The Dutch Media Authorities’ Media Monitor also does not report market shares, only audience shares and financial figures are being reported for the main media groups. For a reliable calculation of market shares, segmented financial data of media groups is needed. This data cannot be found in all media group’s financial accounts.

Based on audience shares the indicators for the concentration of ownership in the radio, television and newspaper markets show a high risk, with joint audience shares of the four largest companies that are between 69% and 91%.

The indicator on Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement scores a medium risk (40%)

The Dutch media legislation does not contain specific limits to prevent a high level of cross-media concentration of ownership. When we look at the marketshare of the top 3 owners across different media markets we estimate that there is a concentration of 84,5%.

A high degree of (horizontal, vertical and/or cross-media) concentration can be prevented through the enforcement of competition rules, including rules on merger control, that take into account the specificities of the media sector. The Autoriteit Consument en Markt (Competition Authority, Authority of Consumer and Market) made the public interest as its explicit goal (ACM, 2013). There are examples of media mergers in which remedies are imposed based on issues such as consumer access (Van der Burg & Van den Bulck, 2015)

The risk related to ‘Commercial & owner influence over editorial content’ scores a low risk (4%) because there are self-regulatory instruments granting social protection to journalists in cases of changes in ownership or editorial line, and that ensure that decisions regarding appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief are not influenced by commercial interests.

Editorial charters of newspapers are not a legal obligation but resulted from an agreement between newspaper publishers and the journalist union. The essence is strict separation of editorial and commercial responsibilities. The Media Act does not require commercial broadcasting to safeguard journalistic ethics in their editorial charter as it is mandatory for public broadcasting. So it is a result of self-regulatory instruments that the appointment and dismissal of editors-in-chief are not influenced by commercial interests.

The indicator on Media viability scores a medium risk (55%). In annual reports of the large traditional media organizations no indications can be found that these media organizations are developing sources of revenue other than traditional revenue streams. For viability this is considered a medium risk. There is no recent data available on the revenues of the audiovisual, radio, and newspaper publishing sector, so we do not know if the revenues increased over the past two years. However we do know that the expenditure for online advertising has not increased nor decreased during that period.

There are however some promising initiatives to develop sources of revenue other than traditional streams. For example there is the Correspondent, a daily, online and advert-free medium that has as a goal to bring news in context with other things that happen in the world. The Correspondent is only accessible online and started after a crowdfunding campaign. That started in September 2013 with 18.000 members and had over 45.000 members in 2016. The website is available in Dutch and some parts also in English. Another initiative is Blendle, they offer the possibility to buy news articles from newspapers and magazines. But instead of having to buy for example a complete newspaper, it is possible to buy just that one article that you are interested in. The initiative started in 2014 and at first it was only possible to read Dutch newspapers and one Dutch magazine, but this increased rapidly. Since 2015 German newspapers are included and Blendle aims to offer more international newspapers in the future. But as said above, these are all new initiatives, from new organisations.

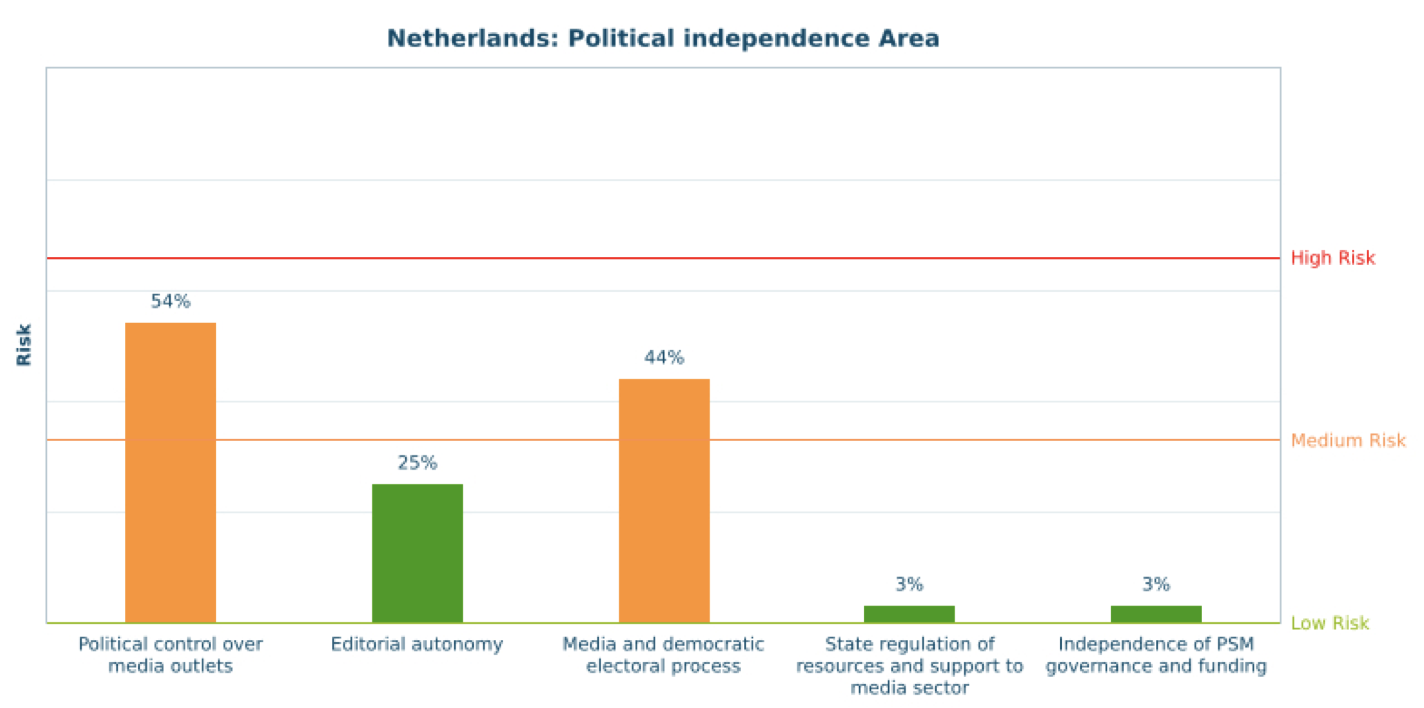

3.3. Political Independence (26% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Three out of five indicators in the Political Independence area score low risk. In particular, State regulation of resources and support to the media sector and Independence of PSM governance and funding score very low, at 3%. Two indicators score medium risk, with Political control over the media outlets at the highest of 54%.

Largely due to the lack of related regulation the indicator Political control over media outlets scores a medium risk (54%). The press is fully unregulated in the Netherlands. The Dutch press policy is based on the ‘free market’ thinking. This also means that there are no laws that regulate possible conflict of interests between owners of media and the ruling parties, partisan groups or politicians. In practice, there are nevertheless no cases of conflict found with regards to media ownership and holding government office. The law also does not contain limitations to direct and indirect control of audiovisual media, radio stations, newspapers, news agencies and media distribution networks by parties, partisan groups or politicians. Nevertheless, none of the largest news agencies or other larger types of media are dependent on political groupings in terms of ownership, affiliation of key personnel or editorial policy.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a low level of risk (25%). There are no regulatory safeguards (e.g. law, statute) that prevent political influence over the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief, however there is no evidence of systematic political interference concerning appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief. The journalistic culture in the Netherlands is characterised with freedom of speech, plurality and self-regulation and has a strong tradition concerning ethic codes and codes of conduct. The Press Council (Raad voor de Journalistiek) is the self-regulatory body for media. Codes of conduct are laid down in the Press Council’s guideline (Leidraad voor de Journalistiek). In addition to the Press Council’s codes of conduct, some media outlets also have their own codes of conduct or other accountability instruments. For example, the public broadcasting association for news and information (NOS), has its own ombudsman for complaints. The largest media outlets in terms of audience are De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad (newspapers), Radio 538, NPO Radio 3FM (radio channels), NPO Nederland 1 and RTL4 (television channels). Apart from De Telegraaf, all media outlets are member of the Press Council. RTL4 is not licensed in the Netherlands but in Luxembourg, and it has to comply with Luxembourg jurisdiction. Nevertheless, RTL’s news broadcast has an editorial charter and recognises the Press Council’s code of conduct via this charter.

The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores medium (44%). No specific rules exist about the participation of political actors in the Dutch public service media’s (NPO’s) news and information programmes. The different codes of conduct are discussed in the NPO’s handbook for radio and television but no specific reference is made to political actors. As editorial charters of news and information programmes of the (national) broadcasting associations are not publicly available, it is not possible to verify whether specific reference is made to political actors in these programmes. This contributes the assessment of risk for this indicator.

The indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector scores a very low risk (3%) because of the existence and effective implementation of regulations that ensure a fair and transparent distribution of state advertisements and subsidies, as well as spectrum allocation.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding is also at low risk (3% ). The law provides a fair and transparent appointment procedure for management and board functions in PSM, which guarantees independence from government or other political influence. The Dutch Public Broadcaster’s (NPO’s) board of directors is appointed, suspended or dismissed by the supervisory board with the minister’s approval, according to article 2.8 Media Act 2008. Since appointment, suspension and dismissal are being done by the supervisory board, the minister’s approval is only considered to be a formality. The composition of and appointment procedures of the supervisory board are described in article 2.5 of the Media Act 2008, and the appointment for a period of at least five years is done by the minister. There is no evidence of systematic conflicts concerning appointments and dismissals.

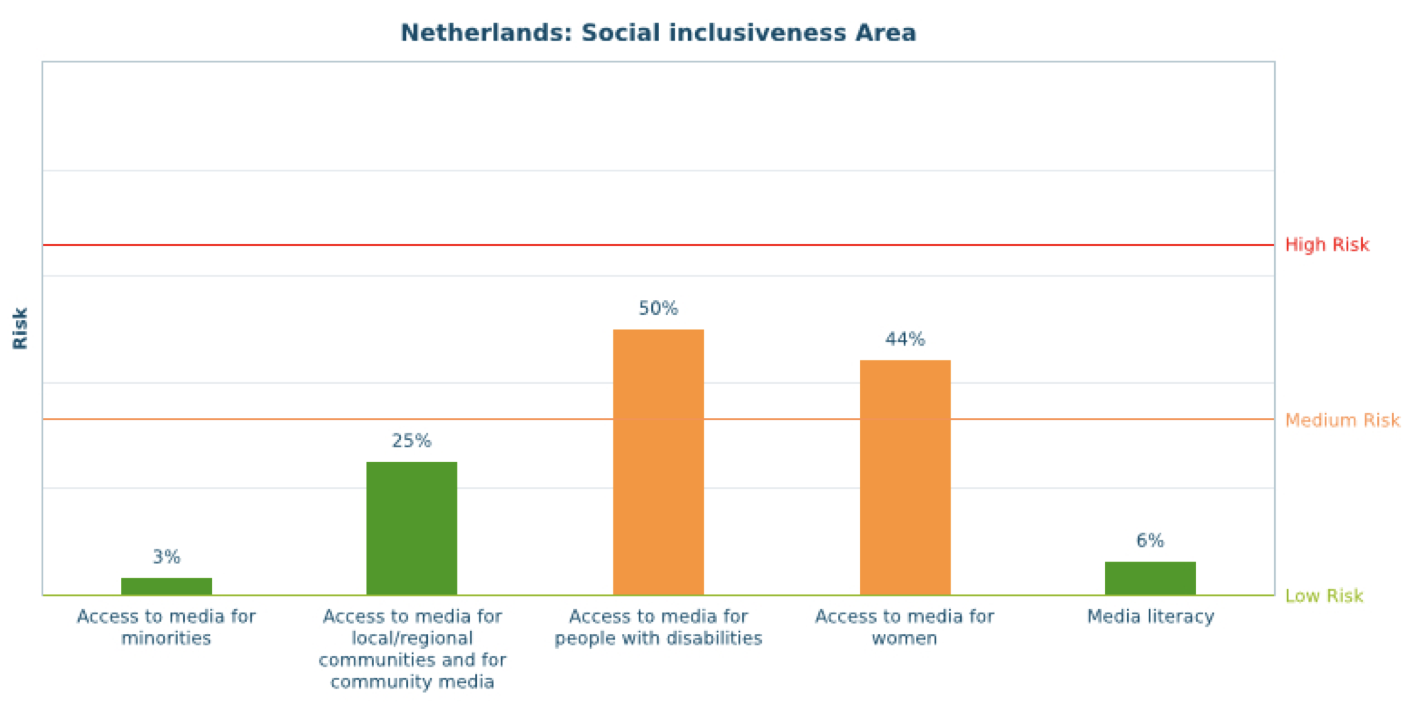

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (26% – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

On average, the Netherlands score low risk on Social Inclusiveness. There are however two indicators which score medium risk: Access to media for people with disabilities and Access to media for women, with respectively 50% and 44%.

The indicator on access to media for minorities scores a low risk (3%). The law guarantees access to airtime on PSM channels to minorities. The Commissariaat voor de Media (Dutch Media Authority, CvdM) issues national airtime to religious and philosophical broadcasting associations (so-called ‘2.42 broadcasts’), article 2.42 Media Act 2008. The access is proportional to the size of their populations in the country, without any significant exception.

The indicator on Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores a low risk (25%)

Although the law grants regional, local and community media access to media platforms, and all 12 provinces of the Netherlands do have regional public media services, there is some cause for concern. According to article 2.170b Media Act 2008 local public service media receive subsidy of 1,30 euro per household in the respective community, this is the responsibility of municipalities. In her evaluation of these local PSM, the Dutch Media Authority concludes that not all municipalities’ subsidies meet the requirements (to little is paid) and one third of the local PSM’s financial situation is concerning [8] (CvdM, 2013 p. 15).

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk (50%) because the policies in place are nascent and the measures taken are fragmented. On the one hand the Media Act 2008 enforces both public and commercial broadcasters, as well as on-demand media services, to provide for subtitles for television content. However, on the other hand it took the Dutch government almost ten years to go ahead with the ratification of the UN treaty Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, making the Netherlands one of the last countries in Europe that needs to change its laws in order to uphold and protect the rights of persons with disabilities as enshrined in the UN Convention. Because of the recent ratification, the Act on equal treatment on the grounds of disability or chronic illness will be changed and there will become an obligation for the media to gradually ensure access to media content by people with disabilities, unless this obligation would be considered to be disproportionate to enact for the media. The law does not give any real certainty for people with disabilities, and it is very unclear if people can actually demand access to media content and services from large media corporations. Compared to broadcasters such as the BBC, it is evident that the Dutch policy is underdeveloped: until very recently audio description for blind people was not even available on TV. Just recently (November 2015) the PSM started with making audio descriptions available for one TV series, and in 2016 for six telemovies. The biggest private TV channel RTL4 only started in January 2016 with audio description for one popular TV series. The second biggest private TV channel SBS6 has got no audio descriptions available.

It is noted by one of the experts that we should monitor the possibility of accessing the internet in the next couple of years: Accessing the Internet is considered to be a growing problem for the visually disabled. Although speech software can in theory be used to navigate the Internet, Internet sites increasingly use plugins and formats that thwart the use of such software. Websites should have a simple layout, so it is easier for visually disabled to use speech software.

The indicator on Access to media for women scores a medium risk (44%). There is an equal rights law that also applies to employment of women in media organizations (de Wet gelijke behandeling van mannen en vrouwen). The “College voor de rechten van de mens” is the Dutch equality body monitoring compliance with the law. Although the College does not have sanctioning/enforcement powers, its advices are being followed in 81% of all cases they handle. The Dutch courts are also obliged to consider the advice of the College if a case is taken to court. The College also has the legal right to go to court and ask a judge to forbid a certain behaviour, or to reverse the consequences of an illicit behaviour. The College has never used this right because of satisfaction with the current effectiveness of the regulatory safeguards. According to the College, the equal rights law is implemented effectively.[9]

However, the indicator on Access to media for women still scores medium risk. This is mainly due to the fact that the PSM has a gender equality policy, which is limited in scope, and also outdated. It also lacks concrete and measurable ambitions. According to the CvdM the situation is actually worse than in 2010. (See:https://www.cvdm.nl/nieuws/npo-haalt-afspraken-maar-nog-steeds-te-weinig-vrouwen-op-televisie/)

The indicator on ‘Media literacy’ is at low risk (6%). There is a well-developed policy and already a strong tradition of policy making in this area. The existing measures are coherent and up-to-date with the latest societal changes. The Dutch government has acknowledged that learning to become media wise is an essential condition for all citizens in order to participate in a multimedia society (McGonagle & Schumacher 2014, p. 38)

4. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the MPM2016, the following two issues have been identified by the country team as more pressing or deserving particular attention by policy-makers in order to promote media pluralism and media freedom in the country:

- The high concentration of media ownership

- The lack of transparency of media concentration

The results of the Media Pluralism Monitor indicate that only in the area of Basic Protection all indicators score low risk. Within all the three other areas there are some medium risks noted, and in the Market Plurality one indicator scores a high risk: the main risk to media plurality in the Netherlands is the high concentration of media ownership. The law does not offer specific thresholds and limits so as to prevent the concentration.

However, based on the current data a stricter anti-concentration regulation cannot be recommended because the small market size could actually be causing this concentration.

There is also some concern about the lack of reliable data as to market share by revenue. Although audience share figures are readily available for television, radio and newspapers, reliable figures for market share by revenue are not. It is recommended that the transparency of media concentration should be enhanced, and that this lack of transparency is addressed by the government by imposing information duties and information rights on the television, radio and newspaper actors.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Mathieu | Paapst | Researcher | University of Groningen | X |

| Trix | Mulder | Research-assistant | University of Groningen |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Thomas | Bruning | Representative of a journalist organisation | The Dutch Association of Journalists |

| Piet | Bakker | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | Hogeschool Utrecht |

| Herman | Wolswinkel | Representative of a publisher organisation | NDP |

| Hans | Van Kranenburg | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Radboud University |

| Edmund | Lauf | Representative of media regulators | Dutch media authority |

| Bart | Brouwers | Academic/NGO researchers on social/political/cultural issues related to the media | University of Groningen |

| Babette | Aalberts | Academic/NGO researcher in media law and/or economics | Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam |

| Anne-Lieke | Mol | Representative of a broadcaster organisation | NPO |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/bevolkingsteller.

[3]https://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=37325&D1=0&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0-4&D6=l&HD=110629-1412&HDR=G5,T,G3,G2,G4&STB=G1.

[4] https://www.eerstekamer.nl/wetsvoorstel/26389_verdrag_inzake_de

[5] https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2016/19/economie-groeit-gestaag-door.

[6] Persvrijheidsmonitor 2015 -Volgenant, O. M. B. J., & McGonagle, T. – 2016.

[7] Evaluatie Commissariaat voor de Media 2007-2011 [Evaluation of the Dutch Media Authority 2007-2011] -DSP-groep – 2013, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/bestanden/documenten-en-publicaties/rapporten/2013/09/17/evaluatie-commissariaat-voor-de-media-2007-2011/evaluatie-commissariaat-voor-de-media-2007-2011.pdf

[8] Evaluation of the funding of local public media institutions in the years 2009-2012 -Commissariaat voor de Media – 2013, https://www.cvdm.nl/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/evaluatie-van-de-financiering-van-de-lokale-publieke-media-instellingen-in-de-jaren-2009-2012.pdf

[9] Elsa van de Loo, beleidsadviseur, College voor de rechten van de mens, 4 july 2016, interview by telephone