Download the report in .pdf

English

Authors: Auksė Balčytienė and Kristina Juraitė

October 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Lithuania, the CMPF partnered with Auksė Balčytienė and Kristina Juraitė, Vytautas Magnus University, who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Lithuanian data collector organized a stakeholder meeting on 05.12.2016 in Vilnius. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

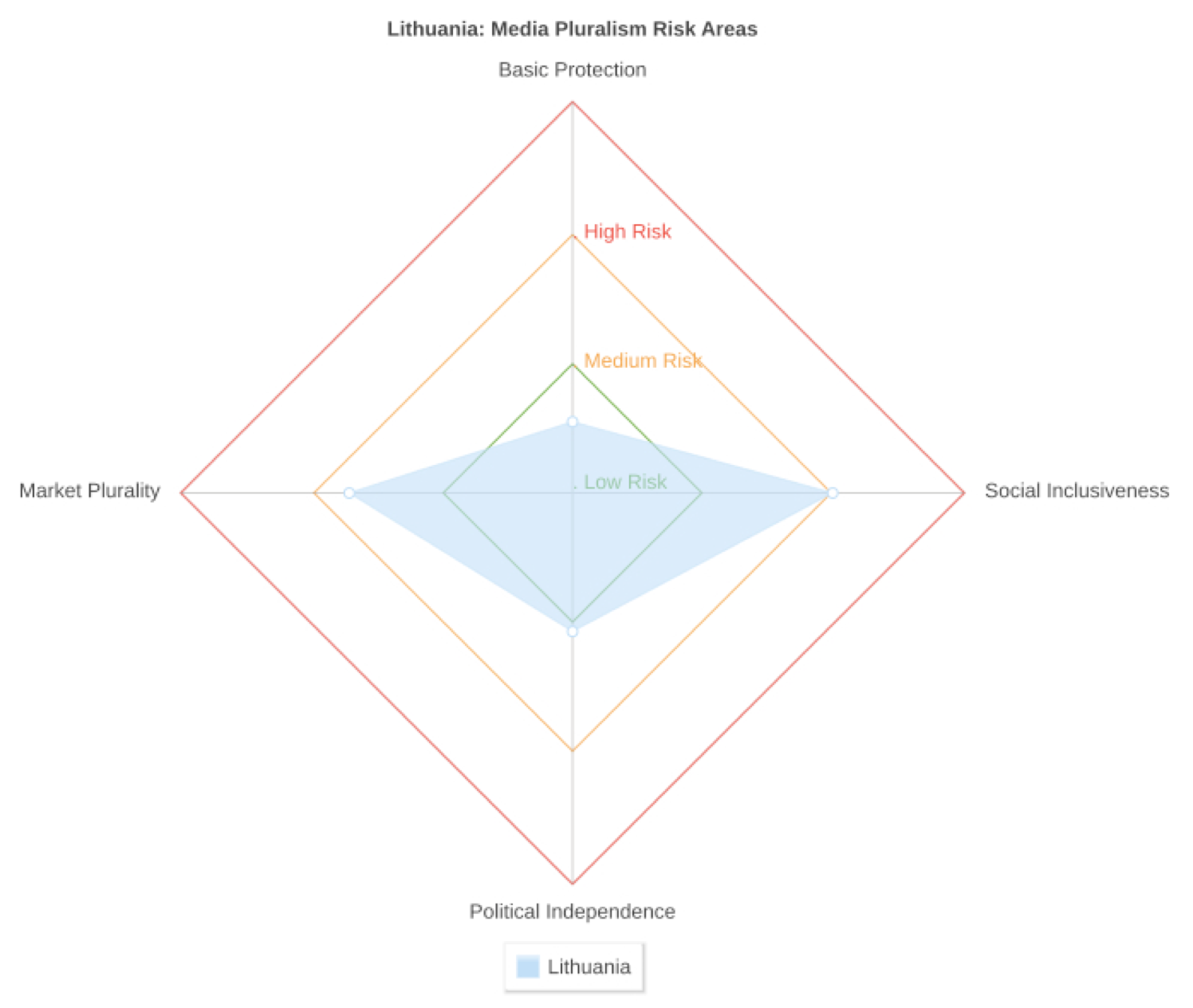

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Lithuania is one of the smallest Central and Eastern European countries, situated on the south eastern coast of the Baltic sea. It is a member of the European Union since 2004 and a member of the Eurozone as of 2015. The country is described as ethnically homogeneous country with Polish and Russian-speaking being the biggest minorities (6,6% and 5,8% respectively of the total population). The official language of the country is Lithuanian. With population of 2,85 million (as of 2016), it can be defined as a small media marketplace, yet relatively varied and dynamic.

The media sector is one of those segments of business which lives under enduring pressure for change and restructuring. The leading news media channels in Lithuania are TV companies, including LRT (public service broadcaster with audience share of 9.8%), LNK Channel Group (overall audience share amounting to 27.4%) and TV3 run by MTG Channel Group (overall audience share amounting to 20.9%). These three TV channels were leaders in terms of daily reached audience: TV3 gathered nearly 37%, LNK and LNK reached 36% of daily audience, and LRT Televizija nearly 30%. Lithuanian radio service launched in 1926 remains one of the most important media with stable audience reach – daily radio reaches 70%, weekly – 85% of the national population aged 12-74. The most popular radio stations include M-1 Channel, LRT Radio (public service radio) and Lietus radio channel with the audience share of 17% each. When comparing different types of media use among the population, it is clear that TV reaches the biggest number of audience per day – 84%; the internet – 64%, radio – 54%, and press – 27%. The most popular online news portals include Delfi, 15min and Lrytas used by majority of Internet users (each of the portals reaching over 1 million monthly users), while print media circulation, readership and income is constantly shrinking. The main national daily Lietuvos rytas lost 2% of loyal audience over the year and was read by 8.6% of population in 2016.[2]

Though financial conditions for some of the media companies have considerably improved (predominantly to the PSM in relation to the abolishment of the advertising on PSM channels and advanced state annual support since 2015), most of the smaller commercial media companies, however, have not fully recovered from the last economic crisis. Print media have been severely suffering from the economic pressures and market share uncertainties, as most newspaper publishers have experienced significant losses of turnover due to falling advertising revenues, declining numbers of subscribers, smaller circulations, and changes in news preferences and consumption patterns of the general audience etc.

In general, among the most illustrative tendencies observed in Lithuania in relation to media production and usage might be listed following observations: on the one hand, media usage is growing (the time spent with information is increasing especially on social networks), but, on the other hand, individualized information usage leads to audience polarization and related media fragmentation; media concentration, in its own turn, is a continuing process, but its effects are becoming even more critical because this gradually eliminates smaller newsrooms and favours consolidation of media into larger groups (media houses) operating in cross-media sectors but with fewer professionals; because of qualitative shifts in the profession of journalism (added stresses on journalistic accomplishment and skills which are required to focus on the attraction of audience and financial gains rather than purely professional ideals) there are changes noticed in editorial decision-making which turns to be driven by managerial choices; furthermore, journalistic content, in general, is shrinking in media channels and discourse turns to be shaped by branding, opinion-formation or marketing purposes[3].

All in all, political culture in Lithuania is defined as conflictive. As in the most of the younger European democracies of Southern and Central-Eastern Europe, political elites in Lithuania are very polarized and divided. Such exceptionality is an outcome of certain features of multi-party politics and weakness of political practice in those countries[4] which run and function on rivalry and confrontations among different elite (or even, as realized in the last elections[5], anti-elite) groups. Though partisan and ideological clashes are a reality in many contemporary democracies, the distinctiveness of such culture in the overall CEE[6] lies in the specificity of political negotiations, which is shaped and determined by the political winner ‘taking all’ to meet political (and quite often also personal) interests and goals. The outcome of such societal arrangements[7] is highly problematic and is registered in fragile and uncertain democratic legitimacy in the whole CEE region which is maintained mainly by lowering institutional trust, public discontent, and rising mainstream and populist promises. Conflictive thinking also permeates the functioning of media in Lithuania: political aspirations are realised through pressures on content (this trend is registered predominantly in regional media).

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Among the most representative societal tendencies identified in the contemporary Lithuanian media marketplace are such deviations, as enduring political influence, on-going media ownership concentration, continuing audience fragmentation and social and political polarization, declining overall institutional trust, and rising societal uncertainty and scepticism. While the diagram below unmistakably depicts worrying nuances in the spheres of social inclusiveness and market plurality where risks are assessed as 66% and 57% respectively, the lasting trend of political influence and related risks to media independence (recognized via political pressures through in-direct ownership[8] and influences on content) are not sufficiently evidently highlighted (the assessed risk level is 35%). Basic Protection is measured as generating low risk (18%), which is an indication that, legally speaking, regulations and related procedures are in place. In short, there is no one cause to be named as critical factor working against media pluralism in Lithuania. The conditions are changing and reasons determining pluralism are indeed varied and complex, but political parallelism and interests appear amongst the most durable and enduring factor contributing to polarization and occurring inequalities (in media access, in media representations).

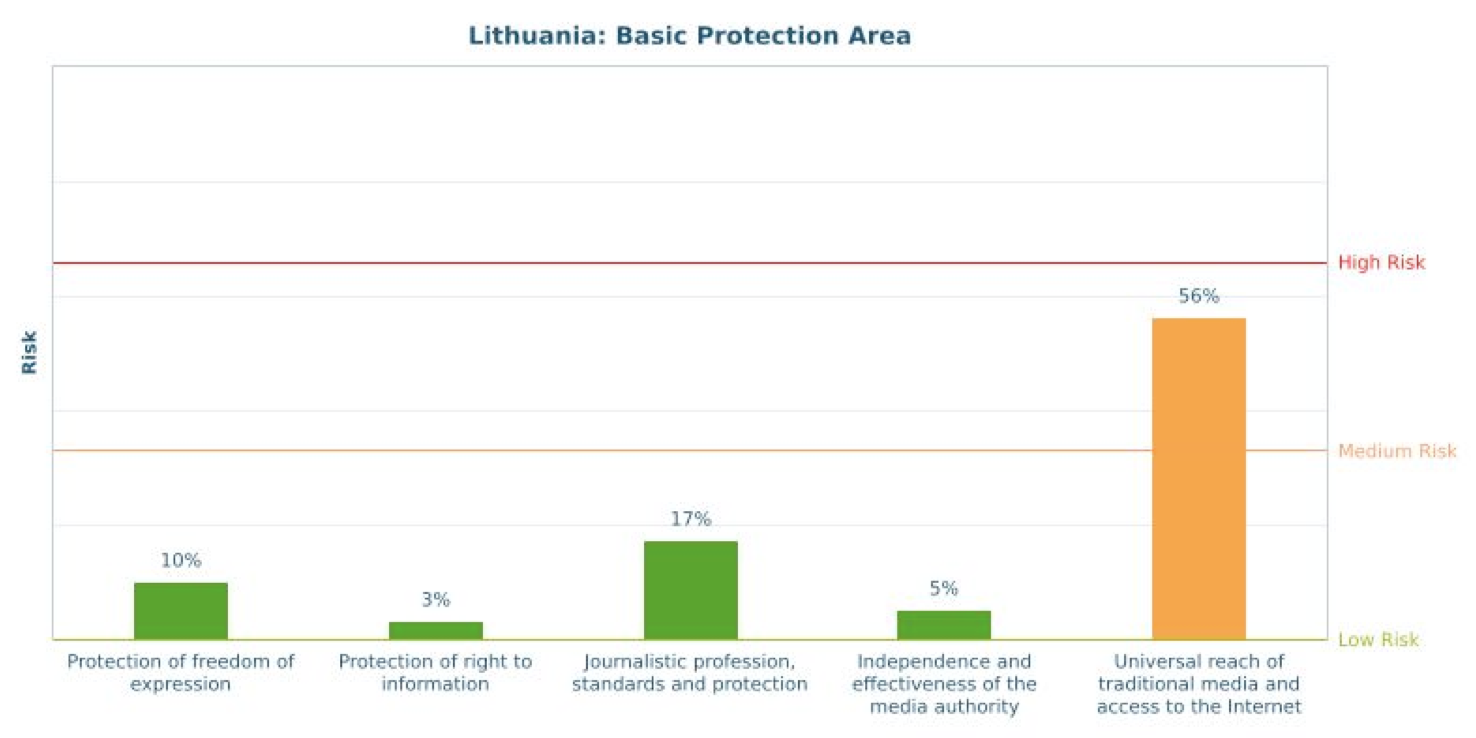

3.1. Basic Protection (18% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

In Lithuania, formally, the overall legal climate for the functioning of media is quite favourable: the basic rights of freedom of expression and right to information are preserved and protected (risks assessed are low: 10% and 3% respectively); also, media regulatory bodies are functioning independently and professionally (risks assessed are also low: 5%). Still, in spite of legal encouragements, the journalistic profession is struggling with constant pressures most of which are determined by specific contextual particularities. Some of these are described as standard (such as economic instability and weakness[9] of the market) whereas other requests (such as perceived lack of public credibility and the need to constantly update their skills) appear as new challenges. Though the overall environment for practicing journalism might seem as rather supportive (for instance, from the point of view of social guarantees[10]), in reality, this is not the case. While effects of the journalistic profession and its standards on the measurement of the overall conditions for pluralism are weighed as low (risk level is estimated of 17%), this result appears to be among the weakest factors in this section. Media professionals are working in an environment that is highly competitive, economically insecure, professionally vulnerable, and hence is susceptible to professional flaws and corruption. The profession is not very well paid and there is a constant movement of specialists within different communication fields: mostly journalists exchange their positions to PR and information management or consulting jobs. Media organizational factors also contribute to this outcome: the majority of the media organizations have no clear rules regulating the work of journalists and editors; direct accountability of editorial offices is also insufficient as there is no regular practice of having editorial lines clearly declared, nor is there a tradition of having an ombudsman position to deal with consumer complaints[11]. Solidarity among journalists is also weak, and the majority of professional journalists are not members of professional organisations. On the one hand, low membership signals that journalists are striving and mainly concerned with their individualistic professional aspirations (which in the long run lowers journalistic solidarity and might affect the general professional culture in the country). On the other hand, professional organisations are doing little to represent the interests of journalists (which affects any organisational reputation and leads to low membership).

The indicator on Independence and effectiveness of the media authority is assessed as 5%, which is a sign of low risk. Though in the past years the media authority (the Radio and TV Commission) has taken recurring initiatives of temporary suspension of the retransmission of the Russian television channel RTR Planeta, these sanctions are performed in accordance with existing legal procedures recognized in the EU and national legislation[12].

Within this section, media reach is yet another indicator which displays a somewhat worrisome tendency. While access to mainstream media and the Internet appear within the medium risk levels (56%), still, this is a sign that might bring serious inequalities in the lengthier perspective. Though with digitalization the informational space turned out to be more easily accessible and diversified, such ‘accessibility’ and ‘pluralisation’ might be only fictional or even made-up. ‘Knowledge gap hypothesis’ suggests one valid explanation, which needs to be addressed by policymakers. It advocates that news consumers with higher socio-economic status tend to acquire complimentary potentials (such as access to qualitatively varied information) out of the increase of media channels, whereas with these changes users with lower socio-economic status remain disadvantaged as they stick to a rather restricted informational portfolio (mostly with commercial channels and entertaining content). By specifying such potential outcome the hypothesis foresees that arising social polarization and inequalities in the country might be based on two issues: (a) low levels of general education and media literacy in the country, and (b) more general socio-economic inequalities.

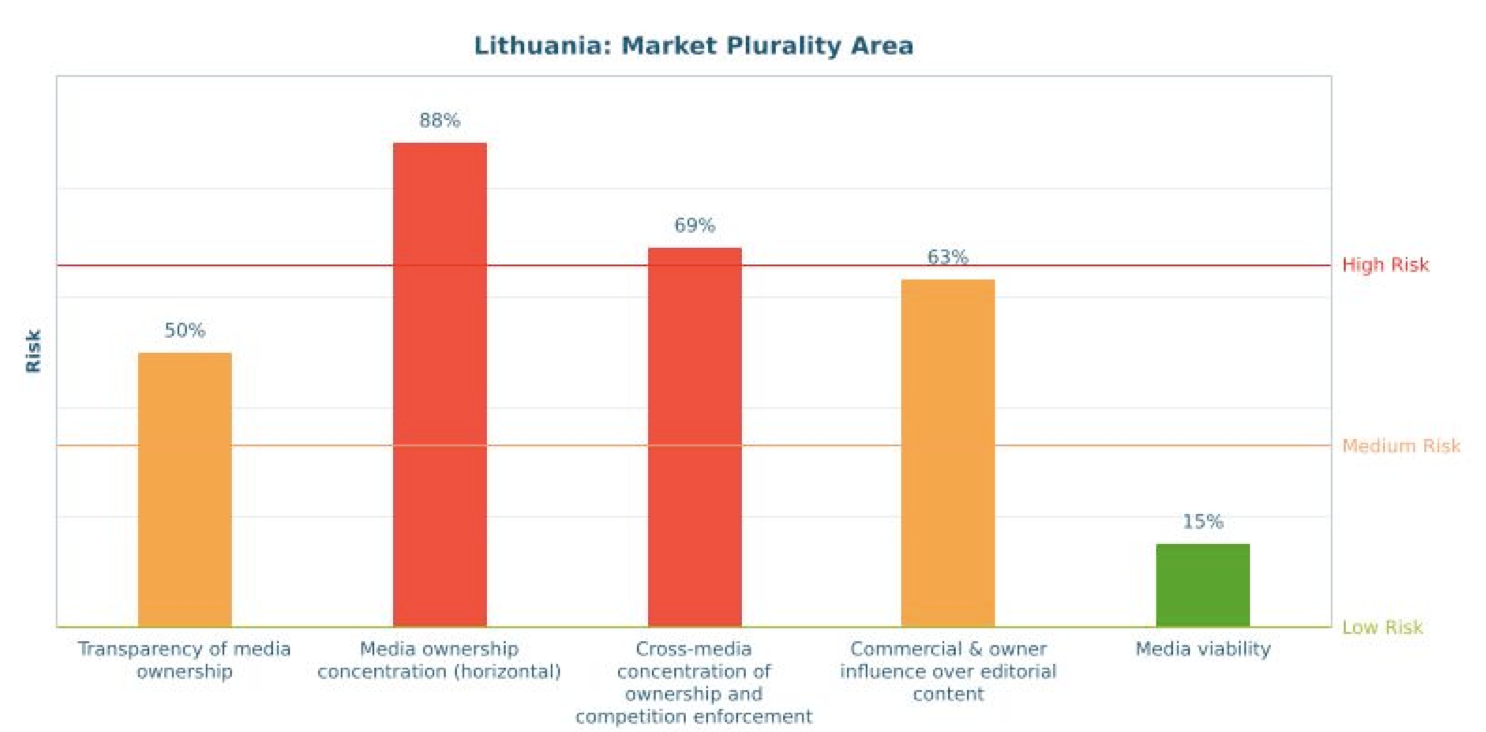

3.2. Market Plurality (57% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

Media ownership in Lithuania remains highly concentrated with a small number of companies owning the majority of the news media market. Though tendencies towards concentration vary depending on the specific media sector, for a small and steadily decreasing market (especially in terms of gradually declining population numbers because of emigration and demographic reasons) the overall tendency of media concentration appears indeed challenging and even troubling.

There are regulatory safeguards and policy measures in place with regard to disclosure of media ownership to the designated authorities, namely the Ministry of Culture. However, in reality, information on media owners is often missing or is outdated. Only a few leading news media declare their ownership information on their own websites as well as only few of them declare their editorial policies (these are mainly PSM group, business daily, few minority and community media groups). No sanctions are imposed on those organizations that do not comply with the legal requirement of media ownership transparency.

Incomplete Transparency of media ownership (medium level risk of 50%) facilitates an environment for increasing media concentration (high level risk of 88%); even more – it affects media professionalism. It also creates space for various influences, and has effect on limited audience awareness of media business related matters, which in its own way affects media literacy. In the longer run, it also produces risks of growing cross-media ownership concentration, which at this moment creates high risk to pluralism (69%). No special legal acts exist in Lithuania that would prevent a high level of ownership concentration within different media or cross-media sectors.

One of the most obvious deficiencies observed in the Lithuanian media regulation is the fact that media diversity (and, consequently, pluralism) is not adequately promoted. All major factors – such as definitions of the ‘dominant position’ in the market, or requests to media to disclose, on a yearly basis, media ownership changes – appear to be in place in the existing media regulations; still these arrangements appear to be insufficient to promote adequate and healthy competition in the market. The media regulating authorities have their own functions, which are mainly related to specific media sectors (print, audio-visual or Internet media), but they do not deal directly with, nor otherwise cover and monitor, the business related aspects (e.g., types of media ownership or competition conditions).

In general, the media industry in Lithuania has been operating in an economically critical and fragile environment: even though the general media market has experienced certain growth (mainly due to the audiovisual and online media market shares), revenues in other media sectors (especially print media) have been steadily decreasing. Newspapers, magazines and other media controlled by private institutions are risking to be biased in favour of their owners (the situation is especially critical with the regional media). This is one of the reasons for Commercial and owner influence over editorial content assessed as reaching a medium risk (63%) to media pluralism. Among other illustrative tendencies recently identified in Lithuania is the reduction of general financial possibilities making media companies increasingly more dependent on the state (through PR-related promotional projects initiated by ministries and other institutions) or other influential political and non-political actors regarding their funding. Though specificities of economic context are crucial to profitable survival and media independence, the indicator measuring risks to Media viability is assessed as low risk (15%) and does not adequately reflect the mentioned problems.

To support media market pluralism, a stronger institutional supervision of largely media business related issues (as well as raising public awareness and interest in media business related matters), and transparency of media ownership appear to be of exceptional significance. As stated, in most cases, all legal requests appear to be in place, yet their enactment and implementation are generally missing.

All things considered, healthy media competition in Lithuania is missing and is not adequately supported through institutional instruments or through competition regulation. Such structural conditions are leading to a situation favourable for a high level of media ownership concentration in the country (as demonstrated in the figure above).

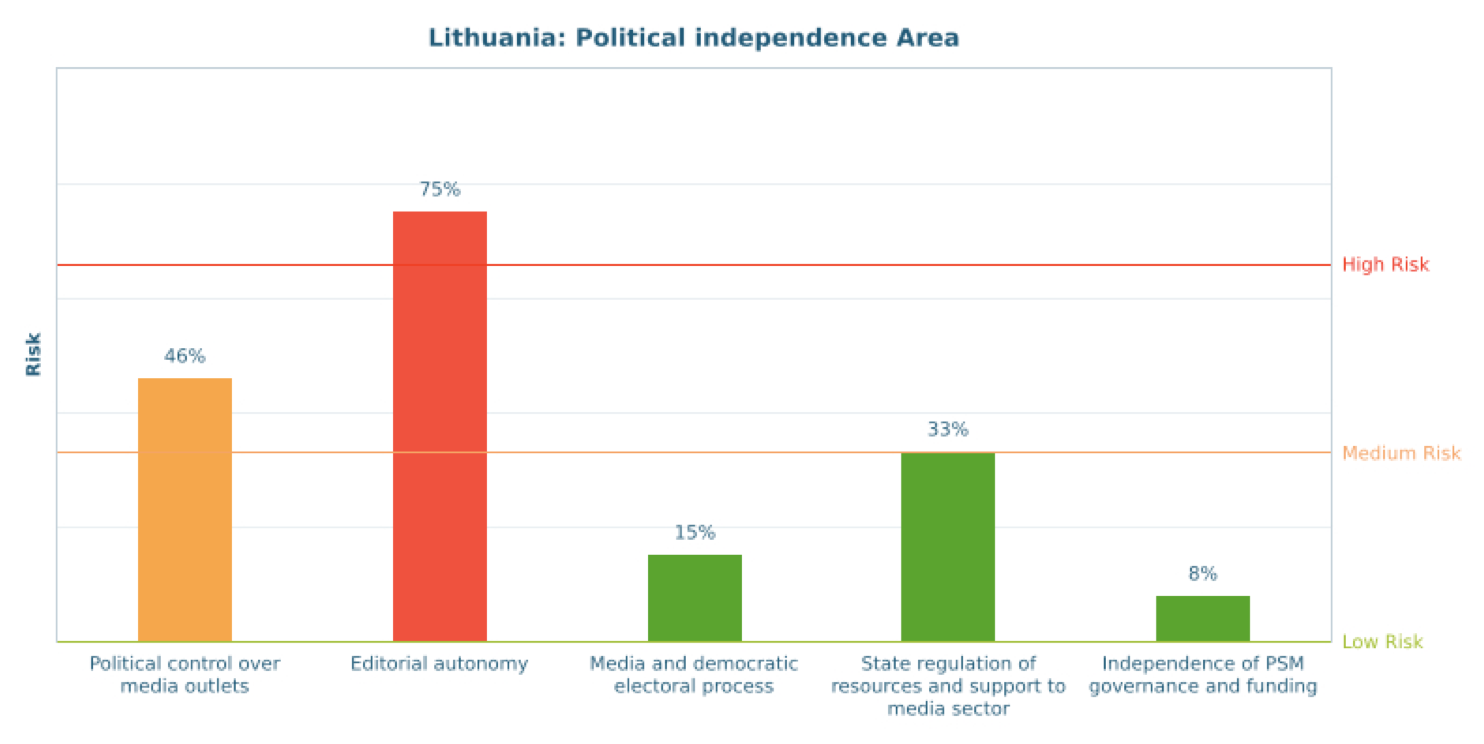

3.3. Political Independence (35% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Legally, many things appear to be in place in Lithuania, though not all of them are functioning in practice. Political parties cannot be owners of media, but political affiliations do exist in reality. This, together with shortages in ownership transparency and weak self-regulatory measures that stipulate editorial independence, result in the medium risk scoring of the indicator on Political control over media outlets (46%). While, as seen from the assessment, political linkages to media ownership are indeed noted and systematic, critical analyses of media policies related to ownership transparency and its impact on news provision, are missing. As suggested in the forthcoming sections, academic institutions could play a much stronger role in raising public awareness of media related matters. A more active role in media performance monitoring could be played by media institutions (e.g., by the PSM): The leading news media do report about media ownership changes, but such news appears in the business section of news outlets, and in most cases they are fact-based and tell nothing about the broader impact of the (political or business influence) tendencies registered. All in all, such informational blurriness creates a fertile ground for overtly favourable reliance of media on political and business interests.

Among the most critical tendencies is the finding that political control of media outlets is under steady increase and editorial autonomy is reduced to critical levels. Therefore, the biggest risk for media pluralism in this area is related to the indicator on Editorial autonomy (75%). As reviewed, because of enduring political and economic pressures and rising new challenges (such as shifting requests for journalistic content, and changed media consumption patterns by the general audience) there is an increasing stress detected in editorial decision making towards production of profitmaking news.

Among other risks within the area of Political Independence, the indicator on State regulation of resources and support to the media sector has to be emphasized. It scores a 33% of risk which makes it low, but bordering with medium. Due to financial instabilities, media industry, especially regional and print media are increasingly more dependent on the state and its support, which, though prevailing and allocated according to transparent procedures, does not guarantee media survival in longer perspective.

National laws and regulatory safeguards provide political actors with equal conditions for representation during election campaigns. The indicator on Media and democratic electoral process, therefore, scores a low 15% risk.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding scores the lowest risk within this area (8%). The PSM has acquired higher level of independence with the implementation of adequate policies towards its funding: two aspects are important here – funding rules and procedures define longer-term (for the term of five years) subsidy, which is calculated in accordance with earnings from public tax. However, the influence of the PSM is rather limited as the channel appears to be trusted but not actually used. The situation with public service media, albeit continuously improving, reflects certain threats to media pluralism, which are mainly linked to low shares of access to LRT channels and representation of community groups.

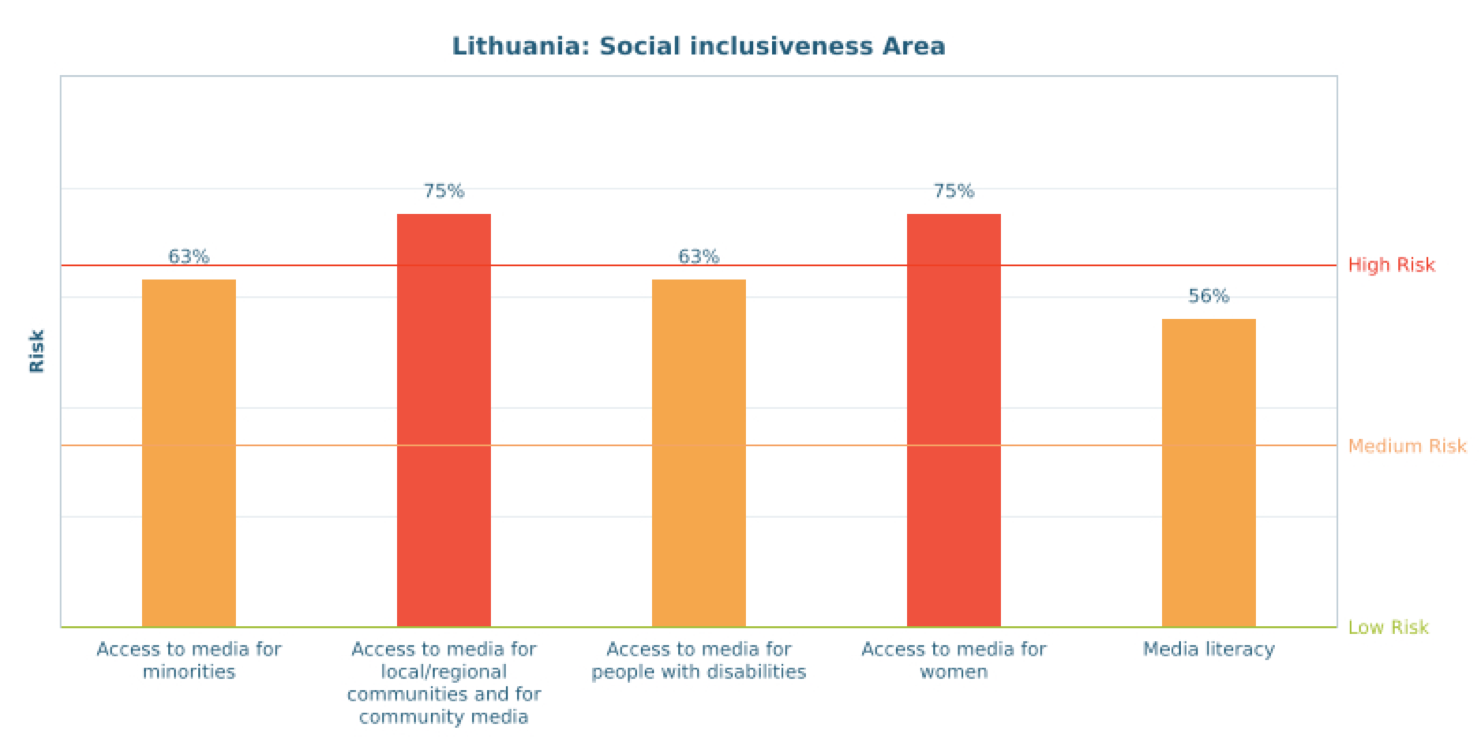

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (66% risk – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Media literacy appears to be a question of high concern (risk score: 56%), predominantly within the current state of affairs linked with increased information wars and propaganda (the latter issue became especially sensitive in the context of the informational attacks, trolling, falsification and lies that are incessantly found in social networks and Russian media channels re-transmitted in the territory of Lithuania). Though discussions about media and information literacy have been active in Lithuania for quite some time, and the government has outlined certain directions (such as the activation of media related analysis skills training in the schools[13]), very few thorough and informed policy-making decisions towards active measures for goal-oriented massive implementation in schools (or elsewhere, like public libraries) has yet taken place in the country. The current situation calls to be defined as an active analysis-oriented stage when several research and methodological projects are funded through different national initiatives[14] and international programmes reinforced by the Nordic Council of Ministers and the British Council. More consistent and ongoing media awareness and practice-oriented education is linked with initiatives and activities of various NGOs[15] and Higher Education Institutions[16]; public intellectuals[17] are also active and their ideas are often taken by the leading news media and are reflected in daily reports. In short, though ‘media literacy’ issues find an adequate place in public debates and public agenda, related policies are still in progress (the measures taken are addressing specific and fragmented matters such as pilot studies of young audiences and their media preferences or media use among the national minority groups).

High level of risk (75%) has been identified for the access to media for local and regional communities, as well as for community media. This is mainly due to the fact that there is no media-related legal mechanisms for equal opportunities to access media for local and/or regional communities and for community media in Lithuania. Similar situation is with women’s access to media (high risk at 75%). Lithuania is among the countries with highest representation of women in media management positions (the average in leading news media is 50% of women working in management – editors, news editors, producers – positions[18]). However, there is no explicit media-related policy on gender equality; the main regulatory framework on non-discrimination and equal opportunities (the Law on Equal Opportunities[19]) is usually applied.

The indicator Access to media for minorities scores medium risk (63%). The law does specify that the minorities have access to airtime on PSM channels (both TV and radio); also, minority media projects are supported by the state through the media support scheme (which, however, runs on project-basis and is not sufficient for long-term funding goals).[20].Predominantly because of these causes Lithuania has been criticized by the EU on the minority rights and media access, including decreasing airtime dedicated for minorities in their language. Recent research show that younger generation of ethnic minorities tend to use more national media in Lithuanian language and in this regard significantly differs from the older generation, which is mainly focusing on minority media and Russian channels.[21]

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities also scores medium risk (63%). The policy on access to media content by people with disabilities is underdeveloped and there is no legislation in place that requires access services for people with disabilities. Even though the main media law[22] guarantees equal access to media for people with disabilities, only PSM has been ensuring (through subtitling and direct translation of selected news programs) the rights to information for people with visual and hearing disabilities.

All in all, the situation in the area of Social inclusiveness is worrisome. This result is mainly linked with competition-focussed reasoning prevailing in media functioning and performance related policies. In regulation, certain aspects of media functioning (predominantly those related to media ownership and competition ruling) appear to be favoured at the cost of others. Though, legally speaking, such preferentialism of particular features appears rather marginal, whereas in reality its outcomes are pretty severe and affect several sectors – from institutional prestige of the media and significance of journalistic professionalism (which is low and steadily decreasing), to audience’s discontent and lack of responsiveness to important issues of societal concern, to side-lining of certain themes and audience groups in media output (which is displayed by risk within the Social Inclusiveness area).

4. Conclusions

In recent years, the use of the media in Lithuania has intensified and noticeably increased. 7 hours and 18 minutes per day are spent on different media by an average media user, encountering 3.5 media types per day. Predominant increase in audience share has been observed among Internet media and social networks: daily reach of online media is 75% of general population and almost 94% of the youngest 15-29 age group. [23]

Though media pluralism, generally, is acknowledged in media policies in Lithuania, the dominant emphasis but absence of supervision of the media’s adherence to competition and transparency aspects is eventually bringing quite reversed results such as rising media concentration and new oligopolies. Also, deficiencies in the observation of existing media-political linkages through ownership structures (which is a restriction stated in the main media law) is treated as a risk affecting content plurality (especially in small, regional outlets).

As a matter of fact, media de-regulation in Lithuania has not actually brought diversity and pluralism in the country; instead, mainstream views and mainstream audiences have taken over, whereas niche interests and interests of minority groups have been significantly marginalised (hence the result in the Social Inclusiveness area is assessed as medium but very close to high risk: 66%). As noticed, the rise of digital communications and interactive media has indeed generated new uses of information; still, such developments resulted in creation of far more diverse, fragmented and polycentric, but also more confusing, messier and even ‘toxic’ informational environments. While social networks have contributed to a certain diversification of informational space, these tendencies have resulted in severe outcomes associated with increasing uncertainty about the quality of distributed news.

Among the most obvious deficiencies observed in the Lithuanian media policy making as well as implementation is the fact that media diversity (and, consequently, pluralism) though sufficiently (i.e., explicitly and unequivocally) endorsed in regulation, in reality it lacks more active promotion and public support. Also, it requires a much closer adherence to new needs of the 21st century, predominantly the adherence both, on the one hand, to media industry requirements and needs, and, on the other hand, audience informational rights and freedoms.

To promote media pluralism and democratic culture on a daily basis, a number of measures must be taken into respect, and the Ministry of Culture (as the main coordinating institution) should express a much more focused leadership role in the elaboration of critical issues relevant for communications arena of the 21st century.

First, since economic conditions for media healthy functioning and competition are unsettling and inconsistent, a much more focussed and coordinated revision of media financial support schemes is needed. For instance, a revision is required of the VAT rearrangements and the channels of media applicable to those; also, the scheme of media subsidies needs to be revised taking into the account emerging channels and means of communications (previously it was mainly the cultural and community press that received support). Additionally, higher sensitivity in available regulation is needed in the sphere of supervision of media business related matters (for e.g., guaranteeing both media healthy competition and media ownership transparency in reaction to pressures from political and business actors).

Second, social inclusiveness needs to be strengthened and promoted by taking into the account both media industry needs (through available regulation) and audience rights (through newly arising freedoms, such as media access and availability, dialogue, privacy and security.

Third, an informed understanding of media literacy and media general awareness is requited (especially in the current context of growing information wars and propaganda), which might be achieved through more strategically focused coordination of available analyses and actions performed by various stake-holders (governmental institutions, academia, NGOs).

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Auksė | Balčytienė | Prof. | Vytautas Magnus University | X |

| Kristina | Juraitė | Prof. | Vytautas Magnus University |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Audronė | Nugaraitė | Vice-chairman | Lithuanian Journalists Union |

| Ainius | Lašas | Lecturer | University of Bath, UK |

| Irmina | Matonytė | Prof. | ISM University, Lithuania |

| Deimantas | Jastramskis | Assoc. Prof. | Vilnius University, Lithuania |

| Deividas | Velkas | Media policy division | Ministry of Culture, Republic of Lithuania |

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

- Date: December 5, 2016

- Place: Vilnius

- List of participants (name, affiliation):

- Regina Jaskelevičienė, Ministry of Culture

- Dainius Radzevičius, Lithuanian Journalists Union

- Audronė Nugaraitė, Lithuanian Journalists Union

- Deimantas Jastramskis, Vilnius University

- Rugilė Trumpytė, Transparency International

- Rasa Jančiauskaitė, Education Development Center

- Neringa Jurčiukonytė, Media4Change

- Nerijus Maliukevičius, Radio and TV Commission

- Martynas Lukoševičius, Radio and TV Commission

- Rasa Navickienė, National Association of Regional Media

- Vaiva Žukienė, Public Information Ethics Association

- Key topics discussed: media policy amendments in relation to media pluralism and diversity; the state and risks in relation to media and information literacy (MIL); cooperation between media industry, self-regulation, monitoring, training and research institutions in relation to media pluralism and MIL

- Conclusions: network of stakeholders in the sphere of media pluralism and media and information literacy (MIL) established

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] KANTAR TNS: Annual Review of Media Surveys 2016 (https://www.tns.lt/lt/top/paslaugos/ziniasklaidos-auditoriju-tyrimai/metine-ziniasklaidos-tyrimu-apzvalga/); Gemius Audience Research March, 2017 (https://www.gemius.lt)

[3] Corresponding measures of coping with such tendencies are suggested by the Ethics Commission which on February 2017 issued an official call to internet media groups to agree on adequate marks indicating to branded content (https://etikoskomisija.lt/item/113-etikos-komisija-interneto-ziniasklaidos-portalus-kviecia-susitarti-del-vieningo-turinio-rinkodaros-projektu-zymejimo)

[4] Rupnik, J. & Zielonka, J. (2013) ‘The State of Democracy 20 Years on: Domestic and External Factors’, East European Politics and Societies, 27(3): 3-25.

[5] ‘The rare country where voters are less worried about immigration than about emigration’, https://qz.com/817538/lithuania-is-a-rare-country-where-voters-are-less-worried-about-immigration-than-about-emigration, accessed Dec 19, 2016.

[6] Bajomi-Lazar, P. (2014). Party Colonisation of the Media in Central and Eastern Europe. Budapest: The Central European University Press.

[7] Balčytienė, A. & Juraitė, K. (2015). The Taste of Crisis: Systemic Changes, Public Perceptions and Polarization in Contemporary Europe. In Trappel, J., Meier, W., and Nieminen, H. (eds.). European Media in Crisis: Values, Risks and Policies. London: Routledge, pp. 20-45.

[8] As reported by Transparency International in 2017, 26 politicians had ownership interests in 57 media channels (https://m.lzinios.lt/app/loadStrApp2.php?rlinkas=Lietuva&linkas=pernai-26-politikai-valde-57-ziniasklaidos-priemones&idas=241532&w=600).

[9] As argued and illustrated in the succeeding sections of this review, financial conditions and other guarantees for the media’s professional performance have steadily declined in recent years resulting in such upturns as growing media concentration, increasing commercial influence on editorial content and decreasing editorial autonomy and independence.

[10] In 2009, the Government imposed social insurance contributions on the income of journalists. By strengthening social security of media workers and increasing taxation, such a step also negatively affected the overall situation of media business, which was already affected by financial difficulties linked to economic crisis. As a result, many journalists lost their jobs, media companies had to economize and reorganize their activities or even were shut down.

[11] Juraitė, K., Balčytienė, A., and Nugaraitė, A. (2016). Lithuania: The Ideology of Liberalism and Its Flaws in the Democratic Performance of the Media. In: S. Fengler, T. Eberwein & M. Karmasin (Eds.): European Handbook of Media Accountability. Farnham: Ashgate.

[12] Official report by the Radio and TV Commision (https://www.rtk.lt/pranesimai-spaudai/sustabdytas-televizijos-programos-rtr-planeta-retransliavimas).

[13] Media literacy education is not included in the school curriculum, only selective cases can be found indicating such activities. Though adequate training methodologies are designed and made publicly available for teachers to acess and apply in teaching. Media literacy promotion related activities are initiated by multiple actors, namely by state authorities (Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Science and Education), educational centers (Ugdymo pletotes centras), international innitiatives (Nordic Council of Ministers, British Council), academic and research institutions.

[14] Leading governmental institutions in the promotion of media and information literacy programs are the Ministry of Science and Education, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of National Defense, the Research Council of Lithuania.

[15] A significant number of public institutions such as Educational Development Center and Media4Change has carried various projects in accordance with MIL ideas; the newly launched Open Society Fund Lithuania (active in Lithuania since April 2017) also will have media literacy guidelines listed among its strategic goals.

[16] Among the higher education institutions most consistently active in MIL-related research and analysis activities are the Department of Public Communications at Vytautas Magnus University, the Institute of International Relations at Vilnius University.

[17] Among the speakers in the field are Auksė Balčytienė, Kristina Juraitė, Audronė Nugaraitė (https://www.bernardinai.lt/straipsnis/2016-12-12-prof-a-balcytiene-emocijos-iveikia-faktus-pernelyg-pasitikime-socialiniais-tinklais/152688; https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/kalba_vilnius/32/157857).

[18] Ross, K., Padovani, C., Barat, E., Azzalini, M. Report on ‘Women and the Media in European Union’ (https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/MH3113742ENC-Women-and-Media-Report-EIGE.pdf).

[19] The Law on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men (https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/488fe061a7c611e59010bea026bdb259?jfwid=q8i88l7y0).

[20] The main national minorities, including Polish and Russian, have a more diversified access to different media in their language. Public service broadcaster LRT airs information of different duration for national minorities in Russian, Belarusian, Polish, Yiddish, and Ukrainian. Periodicals have been published in Russian, Polish and Yiddish as well as news websites are available in Russian and Polish (ru.delfi.lt, kurierwilenski.lt, nedelia.lt, kurier.lt, pl.delfi.lt, zw.pl, zpl.lt, 127.lt, magwil.lt, wilnoteka.lt).

[21] Nordic Council of Ministers Office in Lithuania. Media and information literacy education project in Lithuania (https://www.norden.lt).

[22] The Law on Provision of Information to the Public (https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/2865241206f511e687e0fbad81d55a7c?jfwid=1clcwosx33).

[23] KANTAR TNS: Annual Review of Media Surveys 2016: https://www.tns.lt/lt/top/paslaugos/ziniasklaidos-auditoriju-tyrimai/metine-ziniasklaidos-tyrimu-apzvalga/