Download the report in .pdf

English – French

Authors: Thierry Vedel, Geisel García-Graña and Tomás Durán-Becerra

December, 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In France, the CMPF partnered with CEVIPOF, Sciences Po, who conducted the data collection and commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

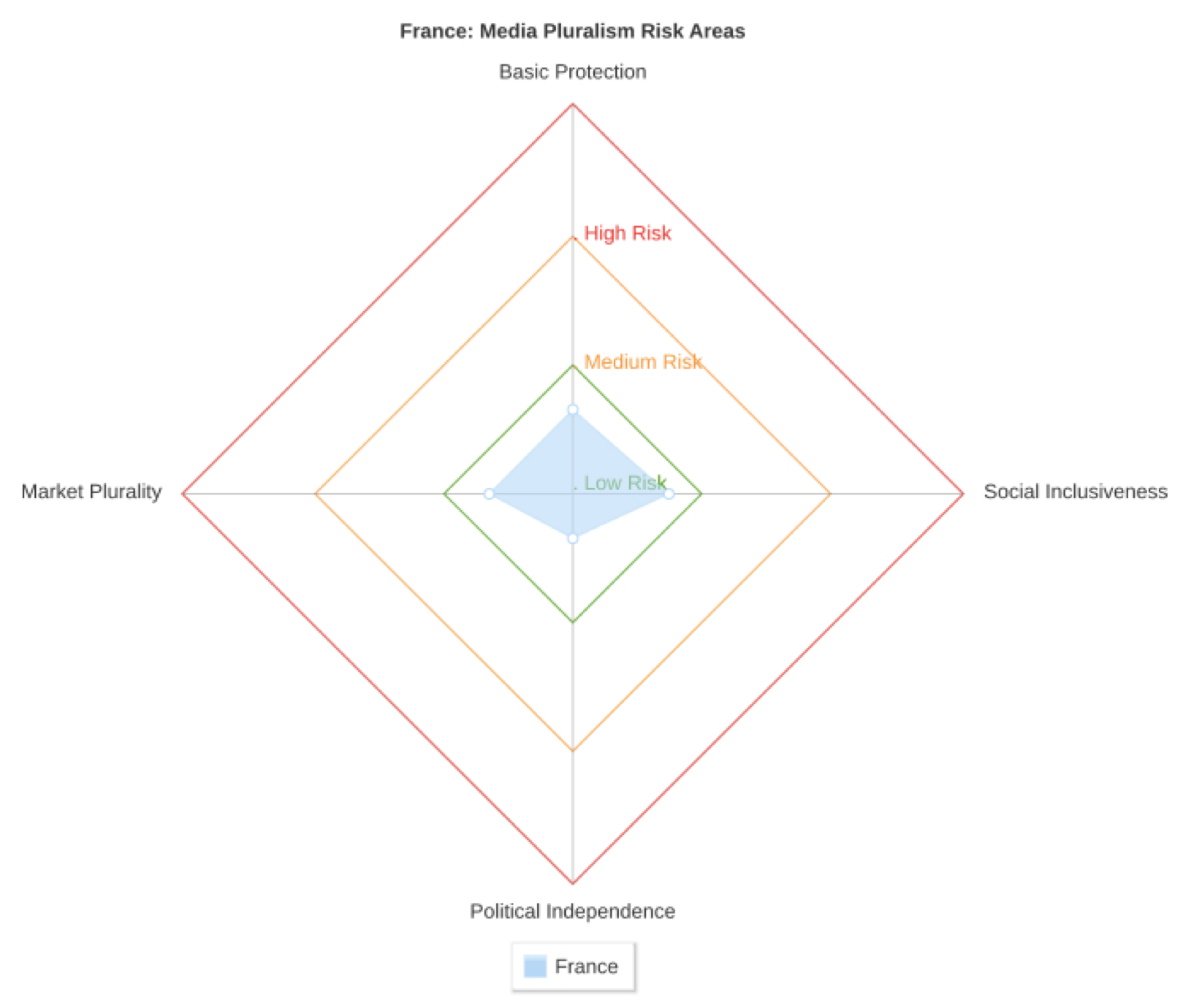

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

With more than 66.6 million inhabitants, France can be divided between two different geographical areas: Metropolitan France, which consists of 96 departments in Europe (64,513,242 people), and the overseas departments and territories –DROM– (2,114,360), for a total of 5 overseas departments and six overseas territories (régions).

The official language in France is French, but there are several regional languages as well and others spoken in France’s overseas territories. 15 local languages are used in the Public Service Media, such as Alsatian, Basque, Breton, Corse, Catalan, Occitan, Picard, Franco-Provençal, Frankish, Normand, Gallo, Champenois, Poitevin-Saintongeais, Kanak languages, Creole languages and Walloon.

France is a heterogeneous society where diversity of origins is very present: 40% of people born between 2006 and 2008 have at least one immigrant parent or grandparent while 10% have both parents who are immigrants. However, France does not recognize minorities based on characteristics of race, ethnic features, skin colour, origin, religion, way of life or sex, which are considered discriminatory criteria by law. In the French Constitution, the definition of the nation is based on the recognition of people with equal rights: “France is an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic. It guarantees equality of all citizens before the law without distinction as to origin, race or religion” (Art. 2). Minorities are not recognized as holders of collective rights, but the heterogeneity of French society is important and recognized by law under the concept of diversity.

Since January 2015 France has been the target of terrorist attacks that led to the adoption of controversial provisions in order to fight terrorism. The state of emergency adopted after the shootings in Paris on 13 November 2015, and its successive extensions, have encouraged debate on civil liberties as the authorities gain greater powers over freedom of expression. The Intelligence Act of 24 July 2015, aiming to prevent terrorism and other threats to national security, has led to threats on confidentiality laws protecting journalists’ sources.

Other important debate has been the proposition of a revision of the constitution to include reference to the deprivation of nationality, allowing the government to strip citizens of their French nationality in the case of dual-citizenship holders convicted of “crimes against the fundamental interest of the nation.” This proposition was finally rejected.

France constitutes one of the most powerful audiovisual industries in the world. 32 channels in metropolitan France integrate the landscape of national television: nine channels are public, 18 are private free-to-air and five are private pay-per-view. Besides national TV, 41 local channels are present in the metropolitan area and 26 public and private channels operate in the overseas departments and territories. By 1 January 2016 the number of national television services with a regulatory agreement, or benefiting from the reporting system, was 268. 27 new agreements with the regulation authority were signed in 2015. After 5 April 2016 DTT channels adopted the standard MPEG-4 which allowed them to broadcast programs in high definition. Some trends in television consumption are the decrease in the audience share of traditional channels and the emergence of the new HD, free-to-air DTT channels launched in December 2012. The video-on-demand market has experienced important growth recently as has interactivity with audiences via social media and multi-screen consumption.

French print media, on the other hand, has experienced more difficulties because of the impossibility to compensate for the decline in its consumption. Online news readership is growing, especially on mobile, but not its monetization, due in part to the practice of ad-blocking (Newman et al., 2016).

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

A general overview of the analysis on media pluralism for France indicates a low to medium risk level for the four main areas examined: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. Among these four areas, Basic Protection shows very few risks. Freedom of expression, protection of the right to information, standards and protection of the journalistic profession and the independence of national authorities are guaranteed by law in France. This is enforced by consistent and complex legal devices and a network of actors working on compliance with the law. However, several policies approved from 2014 to date within the frame of the fight against terrorism have allowed surveillance of the Internet and telephone communications to political powers, which is considered to imply restrictions to certain rights. The Intelligence Act of 24 July 2015 (‘Projet de loi relatif au renseignement’) is an example of the latter. Ministers argue that additional powers are necessary to keep the French people safe.

The state of emergency adopted in November 2015 has been extended several times and remains in force. According to UN Rights Experts, France has adopted “excessive and disproportionate restrictions on fundamental freedoms” as part of the state of emergency and the law on surveillance of electronic communications in the country (United Nations, 2016).

Concerning Market Plurality, more visible risks have to do with the horizontal concentration of media ownership for a medium risk level; indicators of Transparency of media ownership, Media viability and Concentration of cross-media ownership, within the same area, maintain a low risk level. In terms of Political Independence, most of the risks are related to editorial autonomy (medium level). Several regulatory safeguards aim to guarantee independence of journalists and editors-in-chief but they are difficult to implement in practice. More monitor and sanctioning mechanisms are needed. Independence of PSM governance is guaranteed and presents a very low risk level, as well as State support to media sector.

Social Inclusiveness shows a low risk level for most of the indicators. Media literacy policy and activities are well developed and many actors work on the development of this area. On the other hand, the indicator on Access to airtime by minorities is less developed since France does not recognize the concept of “minority.” On the contrary, French model is based on monitoring of representation of diversity, considering socio-professional categories, sex, dissabilities and presumed origin. The 2006 law on equality of opportunity makes the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel responsible for enforcing the respect of representation of diversity. However, the scope of actions of the broadcasters is based on voluntary commitments, which makes difficult the tasks of ensuring representation by the Conseil. (Baromètre de la diversité, 2015).

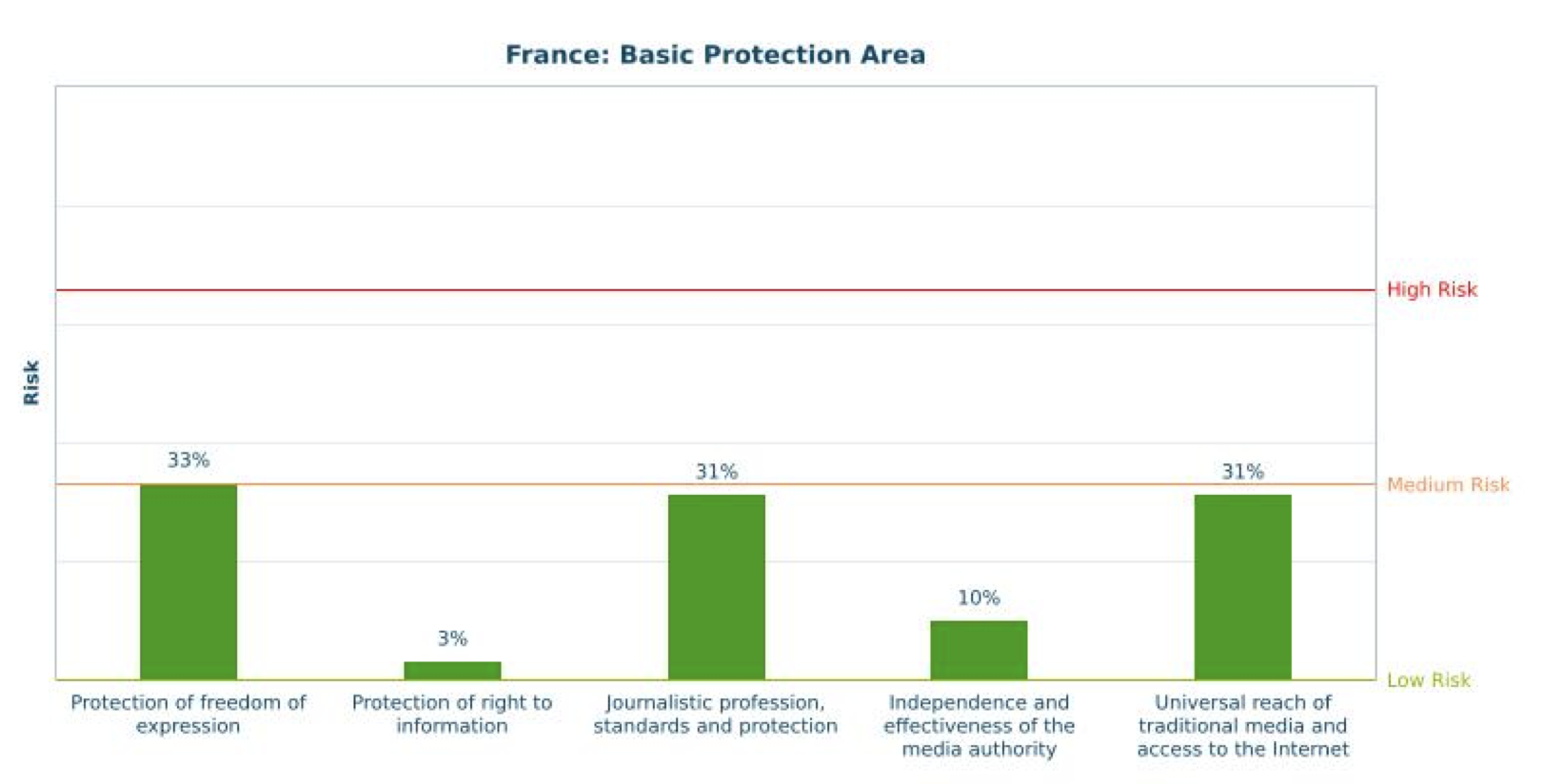

3.1. Basic Protection (22% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

In France the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of Citizens of 1789 recognises the right of freedom of expression as a fundamental right. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for abuses of this freedom as defined by law (Article 11). The main limitations to freedom of expression in France are defined by several laws, such as the Law of Freedom of the Press of 29 July 1881, the Civil Code and the Law of 21 July 2004 to support confidence in the digital economy (Loi n° 2004-575 du 21 juin 2004 pour la confiance dans l’économie numérique). They are related to defamation and insult on the one hand; speech promoting hatred and/or inciting violence, which includes apology for crimes against humanity, anti-Semitic comments, racist, or homophobic remarks; child pornography and copyright infringement, are equally illegal.

However, France has come to a juncture as a result of the terrorist attacks in 2015 and 2016 that has led to the adoption of some provisions restricting these freedoms. Several measures taken under the state of emergency following the terrorist attacks in Paris are likely to require derogation from certain rights guaranteed by the European Convention on human rights. The state of emergency considers the possibility of blocking websites by order of the State. The Intelligence Act, adopted in 2015, also allows authorities to monitor international communications without judicial approval.

The risk for Freedom of expression scores quite high (33%) within the low risk range. With the adoption of Law No. 2014-1353 of November 13, 2014, Strengthening Provisions on the Fight Against Terrorism, the Central Office for the Fight Against Crime Related to Information Technology and Communication (Office central de lutte contre la criminalité liée aux technologies de l’information et de la communication) has implemented procedures for the withdrawal of information, content delisting in Internet search engines and the blocking of websites. In 2015 more than 1,000 applications for withdrawal and delisting were submitted and 283 sites were blocked. On the other hand, the definition of the offense of “apology of terrorism” may be vague and Amnesty International has denounced the prosecution of individuals for statements that did not constitute incitement to violence and which actually fell within the scope of the exercise of freedom of expression.

Risks associated with the right to information scores low as this right is protected by the constitution, national laws and by appeal mechanisms. The Loi n° 78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 (access to administrative data and reuse of public data), amended by subsequent laws or decrees, guarantees the right to obtain the communication of documents created within the framework of a mission of public service by the administration. The Independent body, “Commission d’accès aux documents administratifs”, CADA, effectively supervises implementation of the law.

Regarding the protection of journalists (31% risk), France counts on a strong policy and an extensive network of professional associations[2]. Several instances of self-regulation may be found as internal charters in press enterprises that address deontological and editorial subjects (Le Monde, Le Figaro, Libération, Les Echos, Ouest-France, 20 Minutes and Métro) (Marie, 2014). But in practice, it seems difficult to guarantee the protection of journalists against pressures, censorship and violence. Despite the fact that associations list several actions undertaken to ensure independence, major complaints on their effectiveness can be found. The worst incident took place in January 2015 when two attackers burst into the weekly meeting of Charlie Hebdo and unleashed fatal gunfire on eight journalists. In 2016 the number of media workers targeted by police rose within the framework of demonstrations against new labour legislation. 15 incidents reported during those weeks included attacks by police (using batons, “ash-balls”, tear gas and stun grenades) and by demonstrators (using rocks) (Mapping Media Freedom 2016, 2016).

Protection of journalistic sources is explicitly recognized by the law, but in practice, some violations have taken place. Particularly, under the Intelligence Act, emails and messages exchanged by a journalist and the source are susceptible to being intercepted if the latter is signalled in the fight against terrorism. Intelligence services can obtain and preserve for five years the browsing history of any journalist.

As regards the independence of the media authority (10% risk), various items in the 1986 law on the Freedom of Communication aim to ensure the independence of the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel (CSA) and its members. Law 2013-1028 of 15 November 2013, regarding the independence of public audio-visual services (Loi relative à l’indépendance de l’audiovisuel public), reinforced the independence of the CSA through a new legal status as “independent public authority” and through modifications concerning the appointment of its members. The CSA is composed of a college of seven members: three are appointed by the National Assembly, three by the Senate and one (the president of the Conseil) by the President of the Republic. CSA commissioners are appointed in accordance with the opinion of the commission for cultural affairs acting by a majority of three-fifths of the votes cast. The law states that the appointments must contribute to parity between men and women and are based on competencies or professional experience within the audio-visual sector. The decisions of the CSA do not show any evidence of commercial dependence. However, the conditions for the nomination of the members of the CSA allow links to political power that may affect its character as an independent body.

Universal coverage of PSM has been a constant obligation and national services of public television are diffused and distributed freely to around 100% of the population in the metropolitan territory. Concerning Net Neutrality, the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications (Autorité de Régulation des Communications électroniques et des Postes, ARCEP) is empowered with knowledge of the market. It anticipates possible violations of the principles of net neutrality. This is based on regular exercises of monitoring, such as Observatories of the quality of mobile services, the quality of access to internet service, questionnaires to electronic communications operators on traffic management, and access and data collection on IP-based interconnection. European Union Regulation (EU) 2015/2120 of 25 November 2015 is also applicable. Furthermore, the concentration of Internet Service Providers in France is high as the top 4 concentrate 89% of market shares.

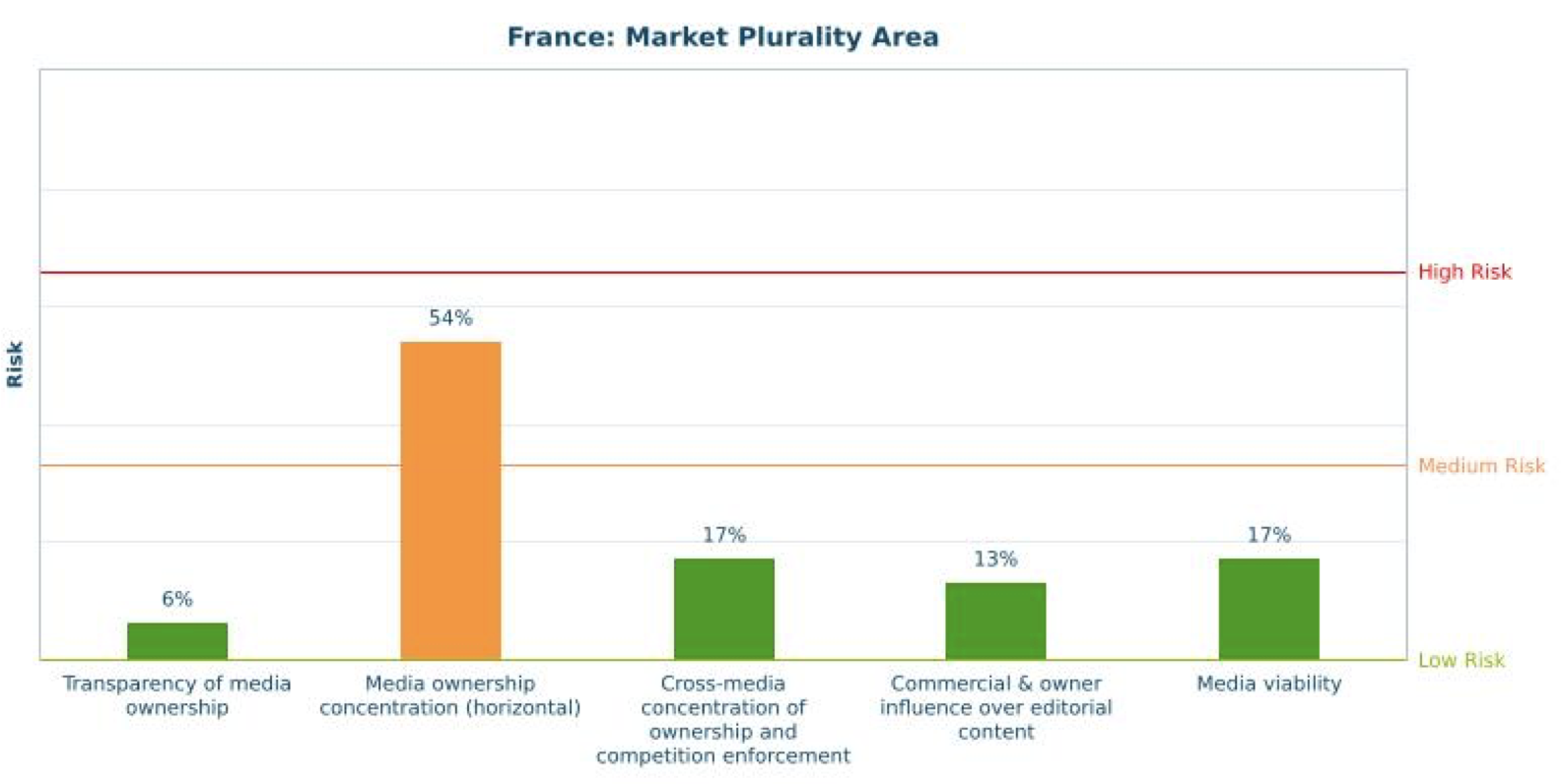

3.2. Market Plurality (21% – low risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The main risks regarding market plurality for France may be found in the area of media ownership concentration (54%). In fact, a well-developed policy has not avoided a concentration in the growth of horizontal and cross-media.

The indicator on transparency of media ownership is at low risk (6%). Transparency on media ownership is guaranteed by Law No. 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on the Freedom of Communication, Law No. 2004-575 of 21 June 2004 to support confidence in the digital economy, and the Law of 29 July 1881 on the Freedom of the Press; these laws state that any editor of a broadcasting service or director of publication must keep certain information permanently available to the public, including ownership. Moreover, authorizations for the use of frequencies for audio-visual services, provided by the CSA, are conditioned by the information on the owner of the service requesting it (Article 29 of the Law on the Freedom of Communication). These provisions are implemented in practice, with several mechanisms monitoring compliance with the law.

The indicator on media ownership concentration is at medium risk (54%). Operations concerning concentration transactions with respect to the audiovisual market are controlled by the CSA to guarantee pluralism and diversity through the power of attributing licenses. This is provided by the Law on the Freedom of Communication. In addition, the Commercial Code stipulates that the Competition Authority (Autorité de la Concurrence) oversees securing transparency in concentration transactions. Law n° 86-897 of 1 August 1986, on reform to the legal regime of the press (portant réforme du régime juridique de la presse), establishes the rules on concentration and transparency for newspapers and prohibits the same person, or group of persons, or entities to own, control or edit daily publications of political and general information whose total distribution exceeds 30% in the national territory of publications of the same kind. Of the nine most important national newspapers, Le Figaro (23,91%), Le Monde (20,58%), L’Equipe-Edition Générale (17,18%) and Aujourd’hui en France (10,68%) concentrate 72% of audiences of newspaper publishing.

Cross-ownership restrictions are regulated by article 41 of the Law on Freedom of Communication, which states that an owner may not be involved in more than two of the following situations at the national level: holding a licence for a television service reaching more than four million viewers; holding a licence for radio services reaching more than 30 million viewers; publishing or controlling daily newspapers with a national market share of 20% — an equivalent rule applies at the regional level. However, some academic and non-governmental associations criticize that mechanisms to avoid cross-media concentration are old and not suitable to the current media landscape. A fact is that Canal+, Bertelsmann, Buygues and Lagardère, the top 4 owners across different media markets, concentrate 75% of the market share.

Regarding newspaper publishing, there is no equivalent to the CSA but the principle of freedom of the press and financial assistance to press companies by the State would guarantee the expression of pluralism of opinions. But as any other society, newspaper companies and groups are subject to the provisions established by the Code of Commerce and EU regulations, so the Ministry of Economy and Finance, through the Competition Authority, must secure transparency in concentration transactions.

The indicator on Commercial and owner influence over editorial content scores a low 13% risk. Regarding the independence of journalists, the Labour Code states two protections to French journalists that allow the latter to leave without prior notice and with rights to compensation when there is a substantial change in the character or editorial policy of its company (clause de conscience) and when there is a change of ownership (clause de cession). Media owners and other commercial entities generally abstain from influencing editorial content. However, the phenomena of concentration and industrialization of the sector tend to lead to an increasing risk in this matter. There have been some incidents considered as censorship derived from commercial influence in Canal. For example, the broadcast of a documentary showing tax evasion and money laundering by a Swiss subsidiary of the bank Credit Mutuel was eventually canceled due to the intervention of the CEO of Canal+ Vincent Bolloré. The owner of Credit Mutuel was a leading financial partner of the Bolloré Group. Also in Canal +, censorship has been denounced when the TV show “Les Guignols” was cancelled by changing the conditions of broadcasting by the same Bolloré.

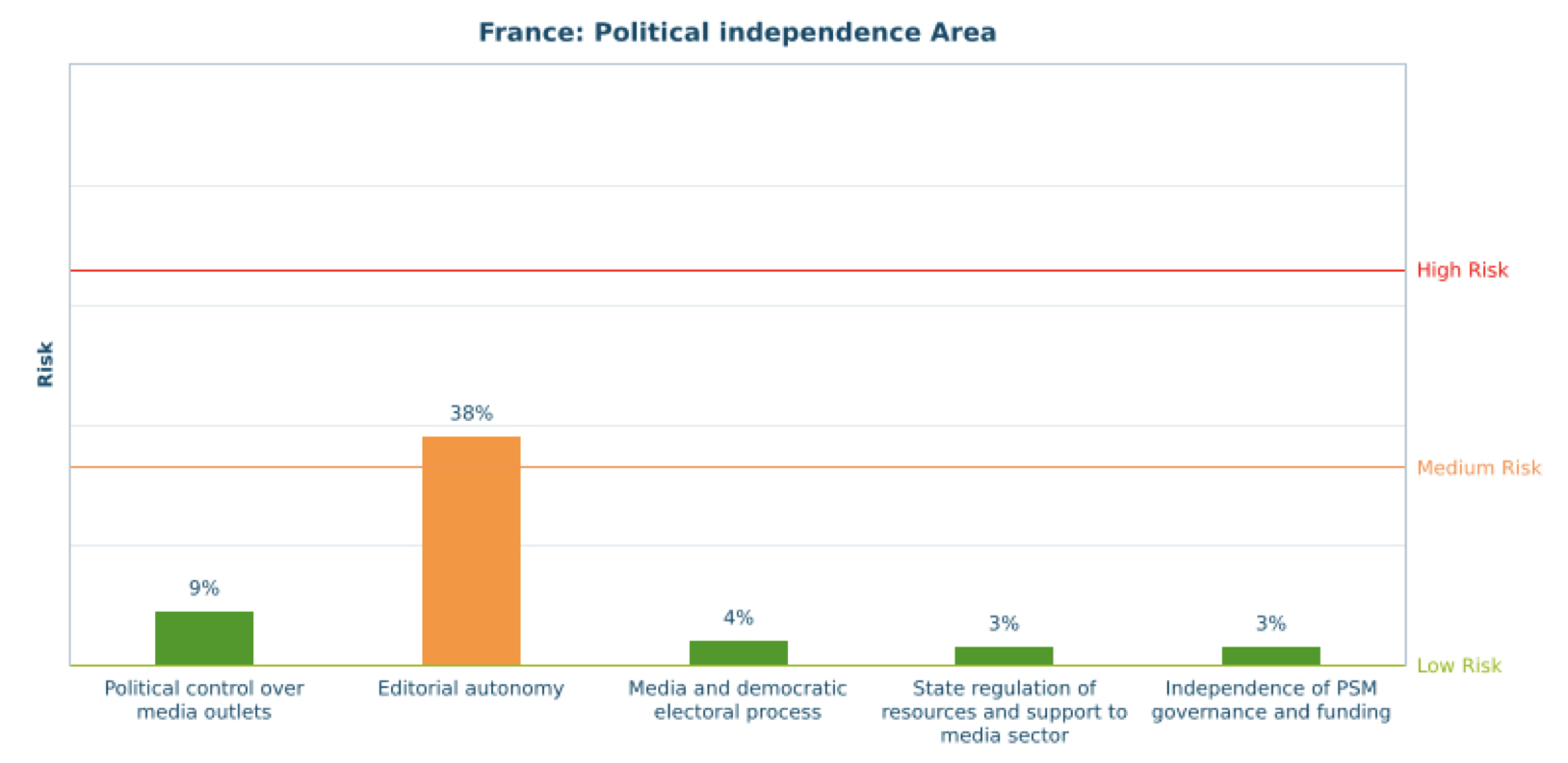

3.3. Political Independence (11% – low risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Political independence of media organizations and media outlets, allocation of state managed resources to media, and the independence of PSM governance are well guaranteed in French law and in practice. Only editorial autonomy is in a situation of medium risk mainly due to the lack of regulatory safeguards to guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief (further than those of the PSM).

The indicator on Political control over media outlets scores a low risk (9%). Newspapers in France can be identified with a political position, but this does not mean that they are subject to political influences or pressures. Some media suspect the influence of the executive power in PSM France Televisions, but scarce evidence is available. To avoid political control over media outlets, French law provides several mechanisms, such as the prohibition of conflict of interest as well as the obligation of members of government to declare their assets to the administrative regulation authority (Haute Autorité pour la transparence de la vie publique — Law on transparency of public life of 2013). There are no direct cases of political control over audiovisual media. However, there could be some cases of indirect influence, mainly due to alliances between politicians and media owners. By law, political parties and politicians cannot own newspapers, TV or radio channels. In France there are about 230 registered news agencies. They are regulated by the law of November 1945, which states that they have the obligation to be transparent and independent. These agencies are represented by the FFAP (Fédération Française des Agences de Presse). More precisely, Agence France-Press is the most important news agency in France with a status that protects its independence (Loi n° 57-32 du 10 janvier 1957 portant statut de l’Agence). In order to ensure Independence, the Administration Council of the Agence France-Press is subject to strict regulations with respect to its composition. Article 8 of the 1957 law establishes that the Council must consist of 15 members: 3 representatives from the public authority, 2 representatives from the public radio and TV sector, 8 representatives from French journals, one journalist and one agent (both professionals).

As already said, Editorial autonomy is the only indicator in this area scoring a medium risk (38%), mainly due to the lack of regulatory safeguards to guarantee autonomy when appointing and dismissing editors-in-chief (further than those of the PSM). However, self-regulation is well developed. To ensure journalistic independence several codes of ethics exist which are addressed to French journalists[3]. Some important media outlets have defined their own self-regulatory measures. For example, the charter of France Télévisions provides that journalists must avoid “any situation that might cast doubt on the company’s impartiality and its independence in relation to pressure groups of an ideological, political, economic, social or cultural nature”. The charter of the group “Le Monde” provides that: “Journalists have the means to exercise their professions and collect and verify information independently of any outside pressure. They prohibit manipulation and plagiarism, do not relay rumors, avoid sensationalism, approximations and biases. They shall avoid any relationship based on interest with the actors of the sectors they write about, and agree to declare any conflicts of interest”. The charter of Radio France International “ensures the pluralist expression of thoughts and opinions, honesty, independence, and information pluralism”. They have also created “independence committees” to monitor compliance with these self-regulations.

In general, groups of political actors are represented in an impartial way when it comes to media coverage. Therefore, the indicator on Media and democratic electoral process scores a low risk (4%). Balance reports by the CSA show that the speaking time of candidates in 2015 elections was respected by PSM channels but not by all the private channels, who received formal notices from the regulatory body for that reason. Two periods are distinguished in the law to guarantee fair representation (outside and during the election campaign). During electoral campaigns a special regime applies: the Conseil publishes a complementary recommendation laying down certain specific rules for the election that the audio-visual media must respect. As provided by article 14 of the Law of Freedom of Communication, advertising broadcasts of a political nature are prohibited.

State regulation of resources and support to media sector is at low risk (3%). Under Article 21 of the Law of Freedom of Communication, the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel (CSA) is responsible for radio spectrum allocations. The use of these frequencies is private within the boundaries of the public domain (a way of privately occupying the State’s public domain). The criteria for their allocation are prioritizing, after operators in charge of public service missions, radio and television services that contribute to the pluralistic expression of thought and opinion and to the diversity of operators, among other criteria (Law No. 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on the freedom of communication, Article 30.1). Analysis of approval and denials on spectrum allocation suggest that this process is done in fair conditions.

Finally, the Independence of PSM governance and funding is also at low risk (3%). The appointment procedures for heads and boards of PSM are laid down by articles 47-1 to 47-5 of the Law No. 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on the freedom of communication. There is no proven influence over appointments or dismissals of PSM General Directors. Nonetheless, in April 2015 the election of the current president of France Télévisions was criticized by some syndicates which denounced archaic, opaque, anti-democratic procedures and abuse of authority by the president of the CSA, who supposedly would have unilaterally changed the procedures for the pre-selection of candidates). The Council of the State, which acts as the supreme court for administrative justice, validated the appointment and rejected the complaints of the syndicates (Delcambre and Piquard, 2016).

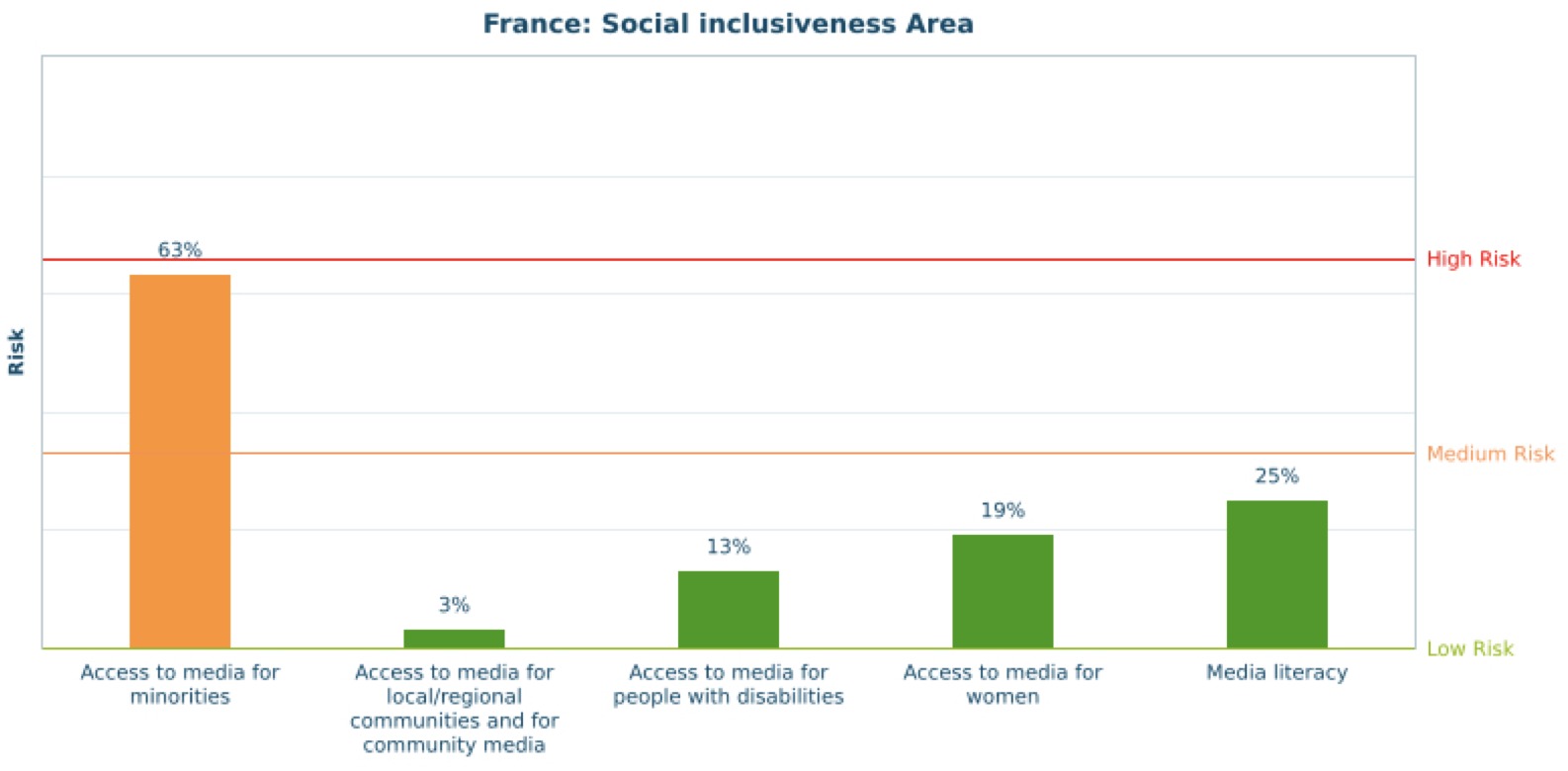

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (25% – low risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

All but one of the Social inclusiveness indicators are assessed as being low risk. The indicator Access to media for local and regional communities and for community media scores minimal risk (3%). Local and regional media, as well as community media, benefit from an adequate level of funding. The majority of French local TV services receive public funding. Several mechanisms to support daily and non-daily press coverage of political and general information at local, regional and national levels also contribute to pluralism and diversity of local media. Funds allocated to local radio stations as well as support to local media through State subsidies seem to be enough. Moreover, in April 2016 the Ministry of Culture established a permanent support programme for community media for the whole territory.

The Access to media for minorities is the only indicator that scores medium risk (63%) in the Social inclusiveness area. The main issues are related to the difficulty to measure the access to media for minorities. Minorities are not recognized as a group with specific rights within French law for which all citizens have the same rights and obligations independent of their origin. The French way of dealing with the issue is the concept of “diversity”: the standard is to achieve a diversification of people appearing on the air so that the diverse backgrounds present in French society can find visibility in programs via journalists, entertainers, candidates, game shows or reality TV, interviewees in news or fictional characters (Obligation by Article 3 of the Law of Communication of 1986). However, this approach does not seem to work in practice. The French media authority, the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel (CSA), reports on under-representation of non-white people, mainly in information shows, and asserts that the more a TV show has to do with French reality, the less diversity it guarantees (Baromètre de la diversité, 2015). There is no specific media which addresses communities such as migrants. France 3 used to have a weekly broadcast called “Mosaïque” (and then “Rencontres”) (1976-1987), which ceased to exist.

The indicator Access to media for people with disabilities scores low risk (13%). Several laws require access services for people with disabilities (Law No. 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on the freedom of communication (Article 33-1) and the Act of 11 February 2005, on equality of rights and chances). Channels whose annual audience exceeds 2.5% of the total audience for televisión are obliged to offer subtitles and programmes accessible to the visually impaired, especially during prime time. Pursuant to the Law No. 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on the freedom of communication, and the Act of 11 February 2005 on equality of rights and opportunities, any channel whose annual audience exceeds 2.5% of the total audience for television must offer suitable services to the deaf or hard of hearing.

The indicator Access to media for women scores low risk (19%). Equal rights laws in France oversee bans on discrimination in appointments as well as differentiations in payment and professional development. Articles L1142-1 to L1142-6 of the Labor Code explain applications and conditions of these provisions (Title IV: Professional equality among women and men. “Titre IV : Egalité professionnelle entre les femmes et les hommes”)[4]. These laws regulate obligations regarding staff representatives and the implementation of measures that aim to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace. Civil sanctions are provided for companies not having an agreement or action plan regarding professional equality. However, just 25% of media organisations declared that they are employing an equal or higher number of women than men in a 2015 CSA study (Rapport relatif à la représentation des femmes dans les programmes des services de télévision et de radio, 2016). The French PSM have developed several programmes to foster gender equality both in content and in personal issues. For example, France Télévisions signed an agreement in April 2014 in favor of professional equality between men and women with the objectives of developing mixed groups in management jobs, fostering the development of women’s careers, guaranteeing equal pay, favoring parentcraft and promoting an appropriate work-life balance. France Télévisions has as well a policy aimed at improving the presence of women on air and promoting the diversification of the image of women, particularly in certain domains as sports.

The indicator Media literacy scores low risk (25%). Media literacy policy in France is at an advanced stage. Significant funds, standards-setting tools, activities are dedicated to media literacy both by media education authorities and by inter-ministrial mechanisms. Media literacy is considered among the fundamental objectives officially assigned to the education system (Decree No. 2006-830 of 11 July 2006 on the common basis of knowledge and skills). Several institutions have the obligation to foster media literacy in and out of schools. Media literacy is included explicitly in the education curriculum as a separate subject (Media and ICT education). It is also prevalent as an inter-disciplinary and cross-curricular subject, and is part of syllabuses at all stages of education: primary, secondary and tertiary. Extracurricular activities on the topic are also very present in the French context, where around 55 key media literacy stakeholders (mostly public authorities and civil societies) take part in several activities developed through a network of partners (‘Mapping of media literacy practices and actions in EU-28’, 2016).

4. Conclusions

Media regulation in France is complex and has reached a satisfactory level of control regarding the risks in terms of media pluralism. Basic protection is guaranteed and political independence of the media is quite envisaged by several regulatory devices and institutions monitoring compliance with the law. The results of the implementation of the Monitor indicate that the main risks to media pluralism in France are within the area of access to media for minorities, a category that is not recognised by law.

The concept of “representation of diversity” is the way to deal with the heterogeneity of French society in the media and this is systematically monitored by the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel. However, several social groups have been found to be underrepresented in French media (Baromètre de la diversité, 2015), which indicates that more efforts are needed to reach a balanced representation of diversity. Modifying the articles concerning diversity in the Law of 30 September 1986 on the Freedom of Communication is recommended in order to establish mandatory commitments for broadcasters and grant the Conseil sanctioning powers.

Media legislation should reinforce the mechanisms that aim to control the concentration of media ownership which is on the rise as this implies an evident risk to democracy and pluralism of opinion. It is also recommended that legislation encourage media ownership by independent groups rather than industry groups, which are susceptible to prompting conflicts of interest. This may be envisaged by providing more public funding accompanied by strict mechanisms to avoid intervention of the State and political powers. Media ownership by independent groups can also be encouraged by giving citizens tax rebates for paying for information or for donating money to media as well as by promoting participation as small shareholders with greater voting rights.

Finally, more monitoring and adequate safeguards against abuse are needed for the use of government powers within the framework of the current state of emergency in the fight against terrorism. Interventions of the executive over the collection, analysis and storage of communications content should be done with prior judicial controls (and not a posteriori, as is currently being done). This is crucial to avoid threats and infringements to the freedom of expression, privacy and other basic rights,

References

Baromètre de la diversité (2015). Paris. Available at: https://www.csa.fr/Etudes-et-publications/Les-observatoires/L-observatoire-de-la-diversite/Les-resultats-de-la-vague-2015-du-barometre-de-la-diversite-a-la-television.

Cagé, J. (2015) Sauver les médias : capitalisme, financement participatif et démocratie. Seuil.

Delcambre, A. and Piquard, A. (2016) ‘France TV : le Conseil d’Etat valide la nomination de Delphine Ernotte’, Le Monde. Available at: https://www.lemonde.fr/actualite-medias/article/2016/02/03/france-tv-le-conseil-d-etat-valide-la-nomination-de-delphine-ernotte_4858798_3236.html.

Digital News Report (2016). Available at: https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2016/france-2016/ (Accessed: 1 April 2017).

Mapping Media Freedom 2016 (2016). Available at: https://mappingmediafreedom.org/plus/index.php/2017/02/28/journalists-in-jeopardy-media-workers-silenced-through-violence-and-arrest-in-2016/.

‘Mapping of media literacy practices and actions in EU-28’ (2016), p. 458. doi: 10.2759/111731.

Marie, S. (2014) Autorégulation de l’information : comment incarner la déontologie ? Paris: Direction de l’information légale et administrative. Available at: https://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/rapports-publics/144000105/ (Accessed: 26 March 2017).

Rapport relatif à la représentation des femmes dans les programmes des services de télévision et de radio (2016). Paris. Available at: https://www.csa.fr/Etudes-et-publications/Les-autres-rapports/Rapport-relatif-a-la-representation-des-femmes-dans-les-programmes-des-services-de-television-et-de-radio-Exercice-2015 (Accessed: 29 March 2017).

United Nations (2016) UN rights experts urge France to protect fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, United Nations human rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=16966&LangID=E (Accessed: 27 June 2016).

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader (please indicate with X) |

| Thierry | Vedel | Researcher | SciencesPo | X |

| Geisel | García-Graña | Research Assistant | SciencesPo | |

| Tomás | Durán-Becerra | Research Assistant |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Nathalie | Sonnac | Commissioner | Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel |

| Arnaud | Mercier | School of journalism Paris 2 | Director |

| Olivier | Da Lage | Member of the executive commitee | Syndicat national des journalistes / Fédération internationale des journalistes |

| Julia | Cage | Assistant professor | Sciences Po |

| Alice | Antheaume | Executive director | School of Journalism – Sciences Po |

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] French journalists enjoy two outstanding protections that are well enforced: the “clause de conscience” (article L7112-5 3° du Code du travail) and the “clause de cession” (article L7112-5 of the Labour Code) which state that when a journalist thinks there is a substantial change in the character or editorial policy of its company or a change of ownership, he or she can decide to leave without prior notice and with rights to compensation.

[3] Charte d’éthique professionnelle des journalistes du SNJ Déclaration de principe sur la conduite des journalistes de la Fédération internationale des journalistes (FIJ), Déclaration des devoirs et des droits des journalistes (international) Charte Qualité de l’information, The project of Code de déontologie pour les journalistes proposé par le comité des onze « sages ».

[4] Other laws are applicable: Loi du 9 novembre 2010 portant réforme des retraites, Loi n° 2011-103 du 27 janvier 2011 relative à la représentation équilibrée des femmes et des hommes au sein des conseils d’administration et de surveillance et à l’égalité professionnelle, Décret n° 2012-1408 du 18 décembre 2012 relatif à la mise en œuvre des obligations des entreprises pour l’égalité professionnelle entre les femmes et les hommes.